Abstract

Background

Pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) experience the highest levels of maternal mortality and stillbirths due to predominantly avoidable causes. Antenatal care (ANC) can prevent, detect, alleviate, or manage these causes. While eight ANC contacts are now recommended, coverage of the previous minimum of four visits (ANC4+) remains low and inequitable in SSA.

Methods

We modelled ANC4+ coverage and likelihood of attaining district-level target coverage of 70% across three equity stratifiers (household wealth, maternal education, and travel time to the nearest health facility) based on data from malaria indicator surveys in Kenya (2020), Uganda (2018/19) and Tanzania (2017). Geostatistical models were fitted to predict ANC4+ coverage and compute exceedance probability for target coverage. The number of pregnant women without ANC4+ were computed. Prediction was at 3 km spatial resolution and aggregated at national and district -level for sub-national planning.

Results

About six in ten women reported ANC4+ visits, meaning that approximately 3 million women in the three countries had <ANC4+ visits. The majority of the 366 districts in the three countries had ANC4+ coverage of 50–70%. In Kenya, 13% of districts had < 70% coverage, compared to 10% and 27% of the districts in Uganda and mainland Tanzania, respectively. Only one district in Kenya and ten districts in mainland Tanzania were likely met the target coverage. Six percent, 38%, and 50% of the districts had at most 5000 women with <ANC4+ visits in Kenya, Uganda, and mainland Tanzania, respectively, while districts with > 20,000 women having <ANC4+ visits were 38%, 1% and 1%, respectively. In many districts, ANC4+ coverage and likelihood of attaining the target coverage was lower among the poor, uneducated and those geographically marginalized from healthcare.

Conclusions

These findings will be invaluable to policymakers for annual appropriations of resources as part of efforts to reduce maternal deaths and stillbirths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite a 38% reduction in maternal mortality ratio (MMR) between 2000 and 2017, about 810 women died each day due to complications of pregnancy and childbirth in 2017 globally [1]. Similarly, two million stillbirths occurred in 2019, despite a 35% reduction since 2000 [2]. The majority of the maternal deaths (66%) and stillbirths (40%) occurred in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1, 2]. Across the globe, SSA still has one of the highest disease burdens, with an 89-fold higher MMR and a 36-fold higher stillbirth rate compared to Europe. Within SSA, MMR and stillbirths vary between [1, 2] and within countries [3, 4]. This variation has been attributed mainly to inequities in access to quality health services, varying levels of poverty, and differences in education attainment [3,4,5,6].

Most maternal deaths and stillbirths are preventable through high-quality care in pregnancy and during and after childbirth [7]. Antenatal care (ANC) is a crucial element of the continuum of care and aims to prepare for birth, prevent, detect, alleviate, and manage pregnancy-related complications that may occur. ANC also presents an opportunity for health promotion among women, families, and communities [8,9,10].

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed the “focused ANC model” in the 1990s to guide routine care at four critical times during pregnancy (ANC4+) [11]. This guideline was revised to eight contacts in the 2016 update to improve the experience of care and minimize the risk of poor pregnancy outcomes [8, 9]. However, in SSA, the proportion of women who meet even the pre-2016 requirement of four ANC visits remains suboptimal. While eight in ten (81.9%) pregnant women in SSA report at least one ANC visit, only 53.4% had at least four visits in 2020 [12]. In Latin America and the Caribbean, 91% of women had ANC4+ visits [12]. The ANC4+ coverage in Kenya (58.5%), Uganda (56.7%) and Tanzania (62.2%) is moderate relative to other SSA countries like Ghana (90.5%) and Liberia (87.3%) [12, 13]. ANC coverage is also heterogeneous within countries in SSA, with wide coverage gaps by residence (rural and urban), maternal education, and household wealth quintile [14,15,16,17].

To reduce maternal and perinatal mortality through ensuring equitable access to ANC services, it is crucial to examine how ANC4+ coverage varies across sub-groups at high spatial resolution [15, 18]. This will inform where and who should be targeted the so-called hotspots requiring action. The WHO-led Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM) working group outlined global targets and strategies for reducing maternal mortality within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) framework [19, 20]. ANC4+ coverage is one of the core priority indicators within the global monitoring and reporting framework [18]. In this framework, at least 90% of all countries and 80% of all districts in a country are expected to have over 70% (target coverage) of pregnant women having ANC4+ visits by 2025 [19]. We apply this target coverage to guide our exceedance probability analysis. Countries also set local targets; Kenya’s targets ANC4+ coverage of 57% by 2020/21 [21], 50% in Uganda by 2021/22 [22] while Tanzania targeted 60% by 2020 [23]. Tanzania is also tracking early ANC coverage (< 12 weeks) aiming a 60% coverage by 2025 [24]. These countries track the targets monthly using routine data supplemented by survey data when available. However, routine data has poor reporting rates and lacks socioeconomic data for equity analysis [25].

Recognizing that relying on broad, aggregate, and national-level estimates masks inherent spatial pockets of sub-national inequities, countries need to evaluate ANC4+ coverage along sub-groups [18, 26] at high spatial resolution. Previous studies have examined ANC4+ coverage across sub-groups in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania [13, 14, 16, 27,28,29,30]. However, none of the earlier studies mapped ANC4+ coverage inequities per sub-group at high spatial granularity. Further, previous studies have not assessed the extent to which EPMM’s ANC4+ target coverage has been achieved overall and across subgroups. Model-based geostatistics (MBG) [31] offers a principled likelihood-based approach to problems concerning the modeling of the spatial variation of a phenomenon of scientific interest such as ANC4+ and robustly assesses attainment of target coverage. It has been applied widely across public health problems where the goal is to make inferences using spatially discrete cross-sectional survey data, especially in low resource settings where disease registries are incomplete or non-existent [32,33,34]. In this study, we aimed to model ANC4+ coverage, likelihood of achieving target coverage and number of women who need to be reached disaggregated by three equity stratifiers (household wealth, woman’s education, and travel time to nearest health facility) using data from household surveys in Kenya, Uganda, and mainland Tanzania. All analyses were at 3 × 3 km spatial resolution and aggregated by district.

Methods

Geographic and country context

Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania are located in East Africa and share national borders (SI Fig. 1). Each country is subdivided into districts that are used for healthcare planning, 47 in Kenya (counties), 135 in Uganda (districts) and 184 in mainland Tanzania(councils) (SI Fig. 1). Population, health, socioeconomic and demographic indicators for each country are presented in SI Table 1. The healthcare system in the three countries is decentralized, running a hierarchical referral system from primary to tertiary level health facilities with both public and private health facilities [21, 22, 24]. These health facilities are expected to serve ANC clients through a recommended package of interventions [8, 9, 11]. The health sector financing in the three countries is mainly dependent on funds from the government, donors, and out-of-pocket payments [35,36,37]. Over time, these countries have put in place policies to make maternal health services, including ANC, affordable and accessible through subsidies, incentives, partial or full removal of user fees, vouchers, conditional cash transfers and insurance programs [29, 38,39,40,41,42]. ANC guidelines monitored ANC4+ coverage at the time of the survey in the three countries [21,22,23,24].

Percentage of pregnant women with at least 4 ANC visits based on the pregnancy preceding their most recent live birth during the 3 years preceding the survey. Empirical observations (A), predicted surfaces at 3 km spatial resolution (B) aggregated at district level (C) and exceedance probability for a 70% target in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania mainland

Data

We used data from the most recent nationally representative Malaria Indicator Surveys (MIS) in Kenya 2020 [43], Uganda 2018/19 [44], and Tanzania 2017 [45]. MIS are stand-alone cross-sectional household surveys which collects data on key indicators of malaria and population health, including that of pregnant women. The sampling strategy is detailed in supplementary information 1 (SI) section A2. Our study sample included ANC history of 10,237 women of reproductive age (15–49 years) for their most recent live birth in the 3 years preceding the surveys. The women belong to randomly selected households within sampled enumeration areas (EAs)/clusters. Each cluster is represented by a displaced geographical coordinate to protect respondent confidentiality [46]. Urban and rural clusters are displaced by up to 2 and 5 km, respectively while remaining within boundaries of the district or region considered in the survey. Further, 1% of the rural clusters are displaced by up to 10 km [46].

Study variables

The outcome variable was the percentage of women who reported receiving ANC4+ visits. Women were asked how many visits they received during pregnancy, and during those visits, to list all types of health providers/professionals they saw. We defined doctors, nurses, midwives, medical assistants, clinical officers, assistant clinical officers, assistant nurses, maternal and child health aides as qualified health professionals for the purpose of ANC provision. Women reporting ANC visits but not listing at least one of these providers were categorized as not receiving ANC. Although the study surveys were conducted during the first phase of implementing the new WHO recommendation of at least eight ANC contacts (ANC8+), none of the three countries had transitioned to the ANC8+ model at the time of data collection or had explicit policy targets for its coverage [21,22,23,24]. Further, the observed ANC8+ coverage based on the study surveys was very low (3.5% in Kenya, 1.4% in Uganda, and 1.2% in mainland Tanzania) insufficient for robust geostatistical modelling at high spatial resolution. As such, analyses in this study were based on the previous WHO recommendation of ANC4+ and in line with the EPMM targets [11, 19]. Study variables were based on factors known to influence ANC use [47,48,49] and data available from the three MIS (Table 1).

Two factors not sourced from the MIS were nighttime lights (NTL) and travel time to the nearest health facility. NTL is a proxy for urbanization, gross domestic product, population density and economic activity [52, 53]. Its inclusion alongside other covariates (Table 1) correlated with the urban/rural clusters in geostatistical models for disease mapping accounts for the sampling design implicitly [54, 55]. Annual NTL, temporally matched to survey year, produced using monthly cloud-free radiance averages, made from low light imaging day/night band data collected by the NASA/NOAA Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite was used [56]. We extracted NTL per cluster within a buffer to minimize the effect of displaced cluster coordinates in ArcMap version 10.5 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA).

We modelled travel time to the nearest health facility (spatial access) using approaches that combine several modes of transport in a single journey [57, 58] based on a least-cost path algorithm implemented in AccessMod software alpha version 5.7.8 (WHO, Geneva, Switzerland) [59]. We accounted for the road network, land use, topography, and transport barriers except where a road intersected a barrier [57,58,59]. We leveraged the SSA master health facility list (MHFL) comprising public health facilities managed by the government, local authority, faith-based and non-governmental organizations capable of offering ANC [57, 60, 61]. The SSA MHFL reflects facilities available around 2015–2018. However, the Kenyan list had been updated (2020) by incorporating data from Kenya’s routine data reporting system and Kenya’s MHFL [62]. We extracted the mean travel time for each cluster as done for the NTL gridded surfaces.

Equity stratifiers

Equity stratifiers were based on factors known to influence ANC4+ coverage, within EPMM recommendations, based on data availability and in WHO’s list of the main barriers to receiving or seeking care during pregnancy [7, 18, 19, 26, 47,48,49]. They included maternal education, household wealth and travel time to the nearest healthcare facility and were stratified as shown in Table 1. The stratification followed a pragmatic approach, with a policy interpretation, supported by literature and ensuring each arm had a considerable number of observations to allow for robust inference using MBG. Districts were then used as the unit of aggregation.

Missing data

Data on maternal autonomy (decision to seek ANC services) were only collected on the Kenya MIS, while data on ANC initiation was not reported on the Tanzania MIS. Women who attended ANC but had a “don’t know” response for the number of ANC visits or when they initiated their first visit were recoded as missing (1.4% in Kenya, 0.6% in Uganda, and 2.1% in mainland Tanzania). However, the three variables with missing data did not exceed 2.1% of the total sample size by country and were excluded from the analysis (SI section A2).

Geostatistical modeling

Spatial exploratory analysis and model selection

Exploratory analysis is the first stage of geostatistical analysis [54]. It entails visualizing the spatial distribution of sampled clusters (Fig. 1A), examining the correlation between covariates, assessing the relationship between ANC4+ and covariates, and testing for residual spatial correlation [54]. We undertook these steps as detailed in SI section A3. Briefly, Pearson’s correlation was implemented in corrplot package in R [63] while empirical logit [64] was used to assess the association between ANC4+ coverage and the covariates and visualized with scatter plots. To select a set of parsimonious predictors used as fixed effects during geostatistical modeling, we used a non-spatial generalized linear model relating the covariates with ANC4+ coverage. The selection was done by country and equity stratifier resulting in 21 models. Finally, we assessed the evidence of spatial correlation after accounting for fixed effects (parsimonious predictors) through an empirical variogram (S1 Section A3).

Parameter estimation and spatial prediction

Separate Bayesian geostatistical models were used to model ANC4+ coverage for each country and equity strata. Each model contained explained factors (fixed effect) and unexplained factors (random effect). The fixed effect was modelled using the predictors denoted as d'(x)β, where d(x) is the vector of parsimonious predictors with the corresponding coefficient β. The random effect was modelled using two terms, S(x) to account for the spatial residual variation and Z to account for the measurement error or small-scale variation that is not captured in S(x). Specifically, the variation in ANC4+ coverage P(x) at location x was modelled using a binomial geostatistical model (Eq. 1).

S(x)was modelled as a zero-mean discretely indexed Gaussian Markov Random Field (GMRF) with Matérn correlation function [65]. All fixed and random effect parameters were estimated using the integrated nested Laplace approximation (INLA) and Stochastic Partial Differential Equation (SPDE) implemented in INLA package [65, 66]. Prediction of ANC4+ coverage was obtained using the simulation from posterior distributions of all the parameters and summarized using the mean, standard error and 95% confidence interval (CI) at 3 × 3 km spatial resolution. The high-resolution surfaces were aggregated by district. Additional details about geostatistical models are provided in SI section A4.

We assessed the likelihood (exceedance probability-EP) that each pixel and district had ANC4+ coverage above 70%, the target coverage based on EPMM strategy [19] (SI section A5). An EP value close to 100% indicates that ANC4+ coverage is highly likely to be above the target; if close to 0%, ANC4+ coverage, is highly likely to be below the target; if close to 50%, ANC4+ coverage, is equally likely to be above or below the target.

Model validation

We validated our models by checking if the fitted correlation function was compatible with the data using a variogram-based procedure [67, 68] detailed in SI section A6. It entailed simulating many variograms from the fitted model and then comparing them with the estimated empirical variogram from the data. We concluded that the adopted correlation function is compatible with our data if the estimated empirical variogram lies entirely in the 95% confidence interval of the simulated empirical variograms.

Computing the number of women with ANC4+ and < ANC4

We estimated the number of pregnant women with ANC4+ visits by multiplying the 3 km gridded surfaces showing ANC4+ coverage from geostatistical models and population gridded surfaces of pregnant women obtained from the WorldPop portal [69]. The number of pregnant women with fewer than four visits (<ANC4+) was obtained by subtracting those with ANC4+ visits from the total number of pregnant women. The results were aggregated by country and district. Briefly, to construct the population density maps, mid-year population of under 1 year (corrected for mortality and migration) were extrapolated by Worldpop based on United Nations (UN) data on births and WorldPop’s estimates of children under 1 year to estimate total annual births. The births were adjusted to match the UN total births by country. The Guttmacher birth to pregnancy rate was used to compute the number of annual pregnancies. Gridded pregnancy surfaces were available for 2020 in Kenya and 2017 for Uganda and mainland Tanzania at 1 km spatial resolution [69].

STATA (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.) was used for descriptive analysis, R statistical software [70] for geostatistical modelling and ArcMap version 10.5 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA) for all cartographies.

Results

Characteristics of study participants and model development

Our study sample included ANC history of 2036 women in Kenya, 3840 in Uganda and 4361 in mainland Tanzania for their most recent live birth in the 3 years preceding the surveys. The descriptive summary of the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of these women are presented in Table 2. The percentage of women with some form of education was high and ranged from 78.3% (mainland Tanzania) to 89.9% (Kenya). Those from poor and poorer wealth quantiles ranged from 38.7% in Kenya to 50.2% in Uganda. Uganda had the highest percentage of women living outside a one-hour catchment area of the nearest public health facility (20.9%), followed by mainland Tanzania (15.4%), and Kenya (7.3%). Exposure to health-related knowledge was high in Kenya (90.0%), relative to Uganda (37.4%) and mainland Tanzania (47.5%) and women in Kenya reported a wider a variety of sources of such information. Model building results are presented in S1 Sections A3, A4, A5, A6, and A8. The validity of the adopted spatial structure of each geostatistical model showed that the assumed spatial correlation function was compatible with our data.

National coverage of ANC4+ visits

Approximately six in ten pregnant women had at least 4 ANC visits, 60.8% (95% CI: 57.0–64.5) in Kenya, 56.4% (53.8–58.9) in Uganda and 60.9% (57.9–63.7) in mainland Tanzania (Table 2). At the national level, none of the countries had achieved the 2025 EPMM ANC4+ target coverage of 70%. However, all the countries had attained their local targets in the survey year, 57% in Kenya by 2020/21, 50% in Uganda by 2020/21 and 60% in Tanzania by 2020. The computed ANC4+ coverage translated to circa 1,362,295 [1,074,933 – 1,626,559] pregnant women in Kenya (2020), 1,378,033 [1,021,299 – 1,708,417] in Uganda (2017) and 1,831,845 [1,360,602 - 2,257,962] in mainland Tanzania (2020). While the percentage of women with ANC4+ visits at the national level was similar, however, due to the different numbers of pregnant women in each country, the number of women with <ANC4+ visits was variable. It ranged from 833,936 [569,672-1,121,298] in Kenya, 982, 535 [652,151-1,339,269] in Uganda to 1,134,884 [708,768-1,606,128] in mainland Tanzania.

Pixel- (3 km) and district- level coverage of ANC4+ visits

Within each country, we found high evidence of spatial heterogeneity in ANC4+ coverage, ranging from 10% to over 95% of women by survey cluster (Fig. 1A) and by 3 km pixels (Fig. 1B). Large parts of northern Kenya, north-western Tanzania (around Lake Victoria) and eastern Uganda had low coverage of ANC4+ (< 50%) compared to the rest of areas in the three countries at pixel level. Conversely, western Kenya (shores of Lake Victoria), southern Tanzania (bordering Mozambique and along the Indian ocean), and parts of northern and southern Uganda had high ANC4+ coverage (over 70%) relative to other parts of the three countries (Fig. 1B).

When the gridded surfaces (Fig. 1B) were aggregated by district (Fig. 1C), overall, 19% (70 out of 366) of all districts had ANC4+ coverage of over 70%. Thirteen percent (6) of counties in Kenya had > 70%, compared to 10% (13) of districts in Uganda and 27% (70) of the districts in mainland Tanzania. Kenya (57% by 2020/21), Uganda (50% by 2020/21) and Tanzania (60% by 2020), had 75, 78 and 61% of districts with ANC4 coverage greater or equal to their local target (Fig. 1C). Additionally, 62 districts across the three countries had ANC4+ coverage of less than 50%: 30 in Uganda, five in Kenya (Garissa, Marsabit, Wajir, Mandera and West Pokot counties), and 27 in mainland Tanzania (Fig. 1C). Only eight districts (Urambo, Itilima, Kasulu, Biharamulo, Kaliua, Kibondo, Kakonko and Bukombe) in mainland Tanzania had ANC4+ coverage of less than 40%. Among the 27 districts in Uganda with coverage lower than 50%, six (Nabilatuk, Moroto, Pallisa, Buvuma Napak and Amudat) districts had the lowest coverage of less than 40% (Fig. 1C).

The results of spatially overlaying population distribution maps with ANC4+ coverage is shown in SI Fig. 18 by district in the three countries. Three (6.4%), 51 (37.8%), and 93 (50%) districts each had at most 5000 women with <ANC4+ visits in Kenya, Uganda, and mainland Tanzania, respectively. On the hand, 18 (38.3%) districts in Kenya had over 20,000 pregnant women with <ANC4+ visits and only two districts in Uganda (Wakiso and Kampala) and three districts (Kasulu, Kaliua and Geita) in mainland Tanzania (SI Fig. 3). There are five outlier districts with over 30,000 pregnant women having <ANC4+ visits in Kenya (Garissa, Wajir, Mandera, Nairobi and Nakuru counties), two in Uganda (Wakiso and Kampala), and none in mainland Tanzania (SI Fig. 3). Garissa, Wajir and Mandera counties in Kenya had the lowest ANC4+ coverage and a high number of women not receiving ANC4+. In addition, Nairobi and Nakuru counties (Kenya) and Wakiso and Kampala districts (Uganda) had a high number of women not receiving ANC4+ despite moderate ANC coverage, due to their high population.

The likelihood of attaining EPMM ANC4+ target coverage of > 70% on the district level with a high likelihood was suboptimal. No districts in Uganda are likely to have met the threshold with a 90% likelihood (Fig. 1D). However, one county (Vihiga) in Kenya and ten districts in mainland Tanzania met this threshold (Fig. 1D). Among the ten districts in mainland Tanzania, five were in Dar es Salaam region (Ubungo MC, Temeke, Ilala, Kinondoni, and Kigamboni) and three districts (Kibaha urban, Kibaha, and Kisarawe) were in the adjacent Pwani region. Conversely, the poorly performing districts, with the least likelihood (< 10%) of attaining the recommended target, were the majority. They covered northern and south-east Kenya, eastern Uganda, and north-western Tanzania (Fig. 1D).

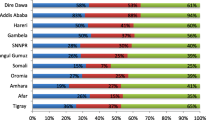

ANC4+ coverage by equity stratifiers

The estimates presented so far characterize overall coverage among pregnant women without considering sub-groups which might mask disparities. ANC4+ coverage among all the equity stratifiers is shown at pixel-level resolution in Fig. 2 and district level in Fig. 3. The corresponding exceedance probabilities at district level are shown in SI Fig. 14. ANC4+ coverage in each stratifier was highly heterogeneous (Fig. 2), with the general spatial variation following that of the overall coverage (Fig. 1). Overall, ANC4+ coverage among the poor (Fig. 2D), un-educated (Fig. 2E) and marginalized from healthcare access (Fig. 2F), was lower compared to the non-poor (Fig. 2A), educated (Fig. 2B) and those within 1-hour of the nearest health facility (Fig. 2C).

Broadly, ANC4+ coverage per district favored the non-poor, the educated, and those living within 1 h of a public health facility (Figs. 2 and 3). Eighty-one (22%) districts had an ANC4+ coverage of over 70% among the educated (Fig. 3B) and only 6 (2%) districts among the non-educated (Fig. 3E), a 13.5-fold difference in the three countries. Similar findings were observed for household wealth (Figs. 2A, D, 3A and D) and travel time to nearest health facility (Figs. 2C, F, 3C and F). Kenya had only one county with an ANC4+ coverage of less than 50% among those with good access (Fig. 3C) compared to 14 counties among the geographically marginalized from healthcare (Fig. 3F) with a similar trend in Uganda and mainland Tanzania.

Irrespective of the household wealth quintile, maternal education status or proximity to healthcare, districts that met EPMM target coverage with a high likelihood were fewer (SI Fig. 14). Further, among the few districts which attained the target coverage with greater than 90% certainty, the majority were among the non-poor, educated and those living closer to their nearest health facility, while the districts unlikely to have met the target (less than 10% certainty) were mainly among the poor, uneducated and those geographically marginalized from healthcare. For example, districts with the poor and uneducated women, there were no districts likely to have met the target coverage across three countries with a high likelihood (SI Fig. 14).

Finally, across all the stratifiers, there is a remarkable pattern of districts with a three-fold burden. That is, intersectionality of vulnerable districts where the same districts has low coverage of ANC4+ among the poor, uneducated and those marginalized from the nearest health facility. These include districts in northern Kenya, eastern Uganda, and north-western Tanzania. Similarly, districts in western Kenya, southern Tanzania, and some parts of northern and southern Uganda had systematic high coverage in all stratification arms.

Discussion

Monitoring ANC4+ coverage and associated inequities requires quantifying and describing the coverage across population groups defined along socioeconomic and geographic equity lines within countries [19, 20]. This should be at a high resolution, the so-called precise public health [71], to highlight hotspots areas within a country. Our findings show that ANC4+ coverage was moderate, with six in every ten pregnant women reporting having received at least four ANC visits in the three East African countries. At the national level, this is short of the 70% coverage anticipated to be achieved by 2025 under the EPMM strategy. However, national targets set by the governments of each of the three countries were achieved. Compared to similar national estimates about decade ago (since 2021), there have been slight improvements. In the early 2010s, between four and five in ten pregnant women had ANC4+ visits - that is, 47.1% in Kenya (2009), 47.6% in Uganda (2011) and 42.8% in Tanzania (2010) [13]. These improvements may be explained by the concerted efforts of stakeholders which included healthcare investment focused on access, training health professionals, decentralized health care, maternal health education, user fees reduction or abolishment among other targeted initiatives [72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80].

However, despite the moderate national improvements and associated efforts, the current ANC4+ coverage is inequitable, and falls short of recommended levels. Yet, the role of ANC in preventing, detecting, alleviating, and managing pregnancy-related complications that might lead to maternal deaths and perinatal mortality is well known. Our findings show the specific districts that have the least coverage and the linked inequities dragging the coverage. This will aid in targeted allocation of resources, subsequent monitoring and evaluation, and benchmarking. This aligns with the SDG mantra of leaving no one behind and starting with the farthest behind, first. The high-resolution maps in Fig. 2 aid in identifying hotspots within the districts with poor coverage, while the exceedance probabilities minimize the chance of misclassifying districts and pixels. This ensures persistent foci of low coverage are correctly identified such that resources are not wasted on interventions and populations who do not require them. We have provided all the district estimates in Additional file 2 for use by policymakers.

The most left behind (lower levels of ANC4+ coverage) districts bore a treble burden where the poorest, with the least education and geographically marginalized from healthcare reside. Women from these districts maybe at a higher risk of maternal mortality and perinatal deaths. There were also districts that had both lowest coverage of ANC4+ and at the same highest number of pregnant without ANC4+ visits. Certainly, resources, and infrastructure are concentrated in wealthier urban places and are scant in poorer and remote areas [81]. The hotspot districts and most in need, include West Pokot, Wajir, Mandera, Turkana, Baringo, Garissa, Elgeyo-Marakwet, Marsabit and Trans Nzoia mainly northern Kenya; Amudat, Moroto, Napak, Nabilatuk, Nakapiripirit, Kalangala, Buvuma, Namayingo, Napaka and Palissa majorly located in eastern Uganda and finally, Kakonko, Biharamulo, Kaliua, Kibondo, Bukombe, Chato, Bariadi TC, Urambo, Nzega, Igunga and Itilima mainly north-west Tanzania.

The hotspot counties in northern Kenya have been historically marginalized, are predominately arid and semi-arid and sparsely populated. The region has poor infrastructure, often stricken by conflict and insecurity which may lead to poor geographic access to healthcare. Further, women in this region have low education attainment, mainly come from poor households, and practice some cultural beliefs antagonist to western medical practices [14, 82, 83]. Likewise, eastern Uganda is among the poorest region in the country and has poor coverage of other maternal and child health indicators [28, 84, 85]. Long distances, poor roads and high transport costs, poor services at the health facilities and lack of access to health-related information also impede women to utilize maternal services in this region [86]. Similar situation exists in North-western Tanzania which is poor and has low conditional probability of transitioning from poor to non-poor status [87]. Further, socio-cultural beliefs, distance, lack of transport, perceived poor quality of ANC services have been reported as barriers to ANC use in this region [88]. Combined in the three countries, these factors provide insights on how to improve the poor coverage in the hotspots. However, our study was concerned with identification of these hotspot through predictive modelling [54], therefore, granular (detailed and context-specific) quantitative and qualitative studies should be conducted to better understand why the districts have been left behind.

Our results showed that the poor had lower ANC4+ coverage. It’s the poor who have the highest disease burden, reduced access to healthcare services and the majority do not utilize health services at all [89]. The pro-rich inequities have been observed before [30] and continue to be persist even among the poor pregnant women who are beneficiaries of government initiatives to improve ANC uptake [80, 81, 89]. Ensuring sufficient and timely reimbursements to prevent out-of-pocket payments and minimizing indirect costs of transport [75, 76, 90] will likely increase uptake among the poor ANC clients where initiatives already exist. It is the poor ANC beneficiaries of initiatives who are negatively affected by stock-outs, dysfunctional medical equipment, shortage of healthcare workers, strikes and discrimination [29, 89] since they cannot afford paying services in the private sector. These bottlenecks require addressing so that the woman who have been left behind can benefit from programs and initiatives put into place. The high ownership of mobile phones in East Africa can be leveraged to create mobile health program simultaneously with community health workers (CHWs) to facilitate follow-ups and minimize socioeconomic barriers [91] among the poor. Determining the degree of follow-up needed based on ANC user characteristics during the first ANC visit can also be used to increase return visits and ANC uptake.

Women without formal education had lower ANC4+ coverage. Maternal education and household wealth and are linked. Women from poor households often have lower educational attainment which negatively affects utilization [92] as observed in the hotspot districts. In the short run, health promotion and outreach campaigns among pregnant will be useful [91, 93] at the village-level [93] or through mass media [94] in the hotspots. This could neutralize harmful traditions and cultural beliefs, misinformation from family or traditional healers, or cases where pregnant women are misled to delay ANC visits [84, 95]. There is a need to raise awareness about new initiatives meant to increase uptake of ANC since lack of awareness has been a barrier in previous initiatives [38, 77, 96]. There is a necessity to integrate and bolster the need for maternity care seeking into educational curriculum. In the long term, higher education attainment will be vital in increasing women’s autonomy, improved access to healthcare information, and may lead to higher socioeconomic status [97] in the hotspot areas.

Long travel time remains a challenge among women in remote areas even where interventions have been implemented [90, 98] and has been linked with lack of public transport and roads in poor conditions [89, 99,100,101]. Access to bicycles has shown to be a pro-poor option in increasing access to health centers and can be used as entry point to intervene on areas with poor geographical access [100], supplemented with contracted transporters [77]. Mobile services could also be implemented to meet the women in their communities [14]. Under the Beyond Zero campaign in Kenya, mobile clinics have provided healthcare to poor and marginalized communities [102]. CHWs are integral in promoting maternal care seeking [103] and might be effective in the hard-to-reach areas [104].

Beyond the demand side challenges, there is also a need to strengthen the supply side to guard against inadequate drugs, equipment, infrastructure, skilled human resources, overburdened health facilities, longer waiting times, reduced health worker motivation and quality of care [38, 72, 75,76,77, 90, 96]. Further, coverage might have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, health workers strikes and absenteeism which were associated with a lower likelihood of attending ANC [105,106,107]. The poor usually bear the burden since they rely mainly on the public sector and cannot afford care from the private sector [108, 109]. The pandemic strained the health system, disrupted essential health services due to inability to access healthcare, transport restrictions, curfew, and fear of contracting the virus when seeking care [110].

Strengths and limitations

The key strengths of our study lie in deriving high resolution maps per each equity stratum, unlike previous studies and if they do, the resolution is course and unsuitable for granular targeting and prioritization. Notable effort is STATcompiler by the DHS program [13] that produces similar estimates as our study and make it publicly available, however, they disaggregate at broad administrative regions. We have also used exceedance probabilities to account for the uncertainty in the data and quantified the likelihood of meeting target ANC4+ coverage, an aspect that has not been considered in previous ANC4+ coverage studies. Another strength is the use of nationally representative surveys which makes our findings to be comparable and generalizable.

Despite the strengths of our study, there are some limitations. There might have been recall bias synonymous with any retrospective data. There was also selection bias since the surveys included women with a live birth 3 years preceding a survey. Women who might have died during pregnancy or with other birth outcomes were excluded. Related to this is the population data that represented all pregnancies; however, ANC visits were asked only when those pregnancies resulted in live births. The conceptual discrepancy might have biased the estimated number of women with ANC4+ visits. The surveys were conducted at different time points across the three countries - Kenya (2020), Uganda (2018/19) and Tanzania (2017)- limiting temporal comparisons between the countries.

The displacement of cluster coordinates due to confidentiality was not accounted for but was minimized by taking averages of estimates within a buffer. Factors that are associated with ANC beyond those collected during the MIS were not considered except for travel time and NTL. We assumed pregnant women used their nearest facility, yet some proportion bypass their nearest facility [111]. We also did not account for weather variation, traffic jams and other factors that affect transport when estimating travel time. Further, having geographical access is not equivalent to either use of care nor its high quality [112]. We used the number of ANC visits with a qualified professional but did not incorporate data on the content or quality of this care, which is critical to the effectiveness of ANC as a maternal and perinatal mortality reduction strategy. We focused on ANC4+ coverage, however, timing of first visit is also critical to achieving four visits. Women who start late, have very low likelihood of reporting ANC4+ visits, which merits examination in a similar way as we did for ANC4 + .

Household surveys provide an opportunity to monitor the coverage, however, they are conducted every 3 to 5 years, limiting tracking at a higher temporal granularity. In addition, sample size from surveys is often limited and inadequate for high spatial resolution risking a covariate driven ANC4+ coverage [113] especially when stratified as we did. On the other hand, routine health data offer an alternative source of information to monitor ANC4+ coverage. However, routine data are limited due to poor reporting rates, challenges in determining accurate catchment population [25] and does not collect socioeconomic datasets relevant to equity assessment. However, routine data can be linked on spatially smoothed equity stratifiers from household surveys and used for equity monitoring. Finally, despite the findings, we cannot infer causality with the cross-sectional survey data that we used.

Conclusions

ANC coverage rates have remained moderate, with about 60% of pregnant women having the recommended four or more visits provided by skilled health personnel in East Africa. The likelihood of attaining district-level target coverage by 2025 is very low. Further, the coverage is inequitable, with women from poor households, without formal education and geographically marginalized from formal healthcare having persistently lower coverage and lower likelihood of receiving at least four visits. The spatially disaggregated information will be valuable to policymakers for improved targeting of annual appropriations and leveraging initiatives aiming to improve coverage of recommended interventions and reducing maternal and perinatal mortality.

Availability of data and materials

The full database of sample household surveys that supports the findings of this study for Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania is available open access from DHS program data portal available to registered users at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- EA:

-

Enumeration areas

- EP:

-

Exceedance probability

- EPMM:

-

Ending Preventable Maternal Mortality

- HIC:

-

High income countries

- INLA:

-

Integrated nested Laplace approximation

- KMIS:

-

Kenya MIS

- LIC:

-

Low-income countries

- MBG:

-

Model-based geostatistics

- MIS:

-

Malaria Indicator Survey

- NTL:

-

Nighttime Lights

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable Development Goals

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- SPDE:

-

Stochastic Partial Differential Equation

- TMIS:

-

Tanzania MIS

- UMIS:

-

Uganda MIS

- WHO:

-

The World Health Organization

References

WHO. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327595

Hug L, You D, Blencowe H, Mishra A, Wang Z, Fix MJ, et al. Global, regional, and national estimates and trends in stillbirths from 2000 to 2019: a systematic assessment. Lancet. 2021;398(10302). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01112-0.

Meh C, Thind A, Ryan B, Terry A. Levels and determinants of maternal mortality in northern and southern Nigeria. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:417. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2471-8.

Tesema GA, Gezie LD, Nigatu SG. Spatial distribution of stillbirth and associated factors in Ethiopia: A spatial and multilevel analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(10). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034562.

Tamirat KS, Sisay MM, Tesema GA, Tessema ZT. Determinants of adverse birth outcome in Sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of recent demographic and health surveys. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1092. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11113-z.

Alvarez JL, Gil R, Hernández V, Gil A. Factors associated with maternal mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa: An ecological study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:462. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-462.

WHO. Maternal mortality: Key facts. 2019. [Accessed 21 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

Tunçalp P-RJP, Lawrie T, Bucagu M, Oladapo OT, Portela A, et al. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience—going beyond survival. BJOG. 2017;124:860–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14599.

WHO. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva; 2016. [Accessed 21 Feb 2022] Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/97892415?sequence=1

Lawn J, Kerber K. Opportunities for Africa’s newborns: Practical data, policy and programmatic support for newborn care in Africa. 2006. [Accessed 21 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.who.int/pmnch/media/publications/africanewborns/en/

World Health Organization. WHO antenatal care randomized trial: manual for the implementation of the new model. Geneva; 2002. [Accessed 22 Feb 2022] Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal_health/RHR_01_30/en/

UNICEF. Antenatal care. 2021. [Accessed 21 Feb 2022] Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/maternal-health/antenatal-care/

The DHS Program. STATcompiler. 2022; [Accessed 25 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.statcompiler.com/en/.

Wairoto KG, Joseph NK, Macharia PM, Okiro EA. Determinants of subnational disparities in antenatal care utilisation: a spatial analysis of demographic and health survey data in Kenya. BMC Health Services Res. 2020;20(1):665. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05531-9.

Bobo FT, Asante A, Woldie M, Hayen A. Poor coverage and quality for poor women: Inequalities in quality antenatal care in nine East African countries. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(5). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa192.

Gupta S, Yamada G, Mpembeni R, Frumence G, Callaghan-Koru JA, Stevenson R, et al. Factors associated with four or more antenatal care visits and its decline among pregnant women in Tanzania between 1999 and 2010. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101893. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101893.

Wong KLM, Banke-Thomas A, Sholkamy H, Dennis ML, Pembe AB, Birabwa C, et al. A tale of 22 cities: utilisation patterns and content of maternal care in large African cities. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(3) Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/7/3/e007803.

Moran AC, Jolivet RR, Chou D, Dalglish SL, Hill K, Ramsey K, et al. A common monitoring framework for ending preventable maternal mortality, 2015–2030: Phase I of a multi-step process. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-1035-4.

EPMM Working Group. Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). Geneva. 2015; [Accessed 21 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/maternal_perinatal/epmm/en/.

United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 2015. [Accessed 21 Feb 2022] Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Ministry of Health Kenya. Kenya Health Sector Strategic Plan 2018–2023.Transforming Health Systems: Achieving Universal Health Coverage by 2022. 2018. [Accessed 22 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.health.go.ke/resources/policies/

Republic of Uganda. Ministry of Health Strategic Plan 2020/21–2024/25, vol. 2021; 2022. [Accessed 22 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.health.go.ug/cause/ministry-of-health-strategic-plan-2020-21-2024-25/

Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. United Republic of Tanzania, Health Sector Strategic Plan (HSSP IV): Reaching all Households with Quality Health Care. July 2015 – June 2020. 2015. [Accessed 24 Mar 2022] Available from: https://www.childrenandaids.org/Tanzania_Health-Sector-Strategic-Plan_2015

Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children. United Republic of Tanzania, Health Sector Strategic Plan July 2021–June 2026 (HSSP V): Leaving No One Behind. 2021. [Accessed 24 Mar 2022] Available from: https://mitu.or.tz/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Tanzania-Health-Sector-Strategic-Plan-V-17-06-2021-Final-signed.pdf

Alegana VA, Okiro EA, Snow RW. Routine data for malaria morbidity estimation in Africa: Challenges and prospects. BMC Med. 2020;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01593-y.

Jolivet RR, Moran AC, O’Connor M, Chou D, Bhardwaj N, Newby H, et al. Ending preventable maternal mortality: Phase II of a multi-step process to develop a monitoring framework, 2016–2030. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1763-8.

Ruktanonchai CW, Ruktanonchai NW, Nove A, Lopes S, Pezzulo C, Bosco C, et al. Equality in maternal and newborn health: Modelling geographic disparities in utilisation of care in five East African countries. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162006.

Rwabilimbo AG, Ahmed KY, Page A, Ogbo FA. Trends and factors associated with the utilisation of antenatal care services during the Millennium Development Goals era in Tanzania. Trop Med Health. 2020;48(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-020-00226-7.

Benova L, Dennis ML, Lange IL, Campbell OMR, Waiswa P, Haemmerli M, et al. Two decades of antenatal and delivery care in Uganda: a cross-sectional study using demographic and health surveys. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3546-3.

Bintabara D, Basinda N. Twelve-year persistence of inequalities in antenatal care utilisation among women in Tanzania: a decomposition analysis of population-based cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open. 2021;11. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040450.

Diggle PJ, Tawn JA, Moyeed RA. Model-based geostatistics. J Royal Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1998;47(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9876.00113.

Ferreira LZ, Blumenberg C, Utazi CE, Nilsen K, Hartwig FP, Tatem AJ, et al. Geospatial estimation of reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health indicators: a systematic review of methodological aspects of studies based on household surveys. Int J Health Geographics. 2020;19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-020-00239-9.

Johnson O, Fronterre C, Amoah B, Montresor A, Giorgi E, Midzi N, et al. Model-Based Geostatistical Methods Enable Efficient Design and Analysis of Prevalence Surveys for Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infection and Other Neglected Tropical Diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab192.

Diggle PJ, Giorgi E. Model-based Geostatistics for Global Public Health. Model-based Geostatistics for Global Public Health; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781315188492.

Chuma J, Okungu V. Viewing the Kenyan health system through an equity lens: Implications for universal coverage. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-10-22.

Zikusooka CM, Kyomuhang R, Orem JN, Tumwine M. Is health care financing in Uganda equitable? African Health Sci. 2009;9(2). https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v9i2.48655.

Renggli S, Mayumana I, Mshana C, Mboya D, Kessy F, Tediosi F, et al. Looking at the bigger picture: How the wider health financing context affects the implementation of the Tanzanian Community Health Funds. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy091.

Dennis ML, Abuya T, Campbell OMR, Benova L, Baschieri A, Quartagno M, et al. Evaluating the impact of a maternal health voucher programme on service use before and after the introduction of free maternity services in Kenya: A quasi-experimental study. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(2). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000726.

Kuwawenaruwa A, Ramsey K, Binyaruka P, Baraka J, Manzi F, Borghi J. Implementation and effectiveness of free health insurance for the poor pregnant women in Tanzania: A mixed methods evaluation. Social Sci Med. 2019:225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.005.

The Governmnet of Kenya. Linda Mama Boresha Jamii, Implementation manual for programme managers. 2016. [Accessed 25 Feb 2022] Available from: 1. http://www.health.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/implementation-manual-softy-copy-sample-1.pdf.

The Republic of Uganda. Roadmap for Accelerating the Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Mortality and Morbidity in Uganda 2007–2015. 2008. [Accessed 2 Mar 2022] Available from: http://library.health.go.ug/publications/maternal-health/roadmap-accelerating-reduction-maternal-and-neonatal-mortality-and

Improving maternal and newborn care in northern Uganda. Published by USAID Applying Science to Strengthen and Improve Systems (ASSIST) project. Bethesda; 2017. [Accessed 2 Mar 2022] Available from: http://library.health.go.ug/download/file/fid/1180

Division of National Malaria Programme (DNMP) [Kenya], ICF. Kenya Malaria Indicator Survey 2020. Nairobi and Rockville; 2021. [Accessed 22 Feb 2022] Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-MIS36-MIS-Final-Reports.cfm

Uganda National Malaria Control Division (NMCD), Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), ICF. Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey 2018–19. Kampala and Rockville; 2020. [Accessed 22 Feb 2022] Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-MIS34-MIS-Final-Reports.cfm

Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children (MoHCDGEC) [Tanzania Mainland], Ministry of Health (MoH) [Zanzibar], National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of the Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), ICF. Tanzania Malaria Indicator Survey 2017. Dar es Salaam and Rockville; 2018. [Accessed 22 Feb 2022] Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-MIS31-MIS-Final-Reports.cfm

Perez-Heydrich C, Warren JL, Burgert CR, Emch ME. Influence of Demographic and Health Survey Point Displacements on Raster-Based Analyses. Spatial. Demography. 2016;4(2). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40980-015-0013-1.

Okedo-Alex IN, Akamike IC, Ezeanosike OB, Uneke CJ. Determinants of antenatal care utilisation in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031890.

Adedokun ST, Yaya S. Correlates of antenatal care utilization among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from multinomial analysis of demographic and health surveys (2010–2018) from 31 countries. Arch Public Health. 2020;78(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00516-w.

Tessema ZT, Minyihun A. Utilization and Determinants of Antenatal Care Visits in East African Countries: A Multicountry Analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. Adv Public Health. 2021;2021. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6623009.

Rutstein SO, The DHS. Wealth Index: Approaches for Rural and Urban Areas. Calverton; 2008. (DHS Working Papers). Report No.: WP60. [Accessed 25 Feb 2022] Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP60/WP60.pdf

dos Anjos LA, Cabral P. Geographic accessibility to primary healthcare centers in Mozambique. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0455-0.

Mellander C, Lobo J, Stolarick K, Matheson Z. Night-time light data: A good proxy measure for economic activity? PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139779.

Bagan H, Borjigin H, Yamagata Y. Assessing nighttime lights for mapping the urban areas of 50 cities across the globe. Environ Plan B Urban Analytics City Sci. 2019;46(6). https://doi.org/10.1177/2399808317752926.

Giorgi E, Fronterrè C, Macharia PM, Alegana VA, Snow RW, Diggle PJ. Model building and assessment of the impact of covariates for disease prevalence mapping in low-resource settings: To explain and to predict. J Royal Society Interface. 2021;18. Royal Society Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2021.0104.

Utazi CE, Nilsen K, Pannell O, Dotse-Gborgbortsi W, Tatem AJ. District-level estimation of vaccination coverage: Discrete vs continuous spatial models. Stat Med. 2021;40(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8897.

Elvidge CD, Zhizhin M, Ghosh T, Hsu FC, Taneja J. Annual time series of global viirs nighttime lights derived from monthly averages: 2012 to 2019. Remote Sensing. 2021;13(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13050922.

Ouma PO, Maina J, Thuranira PN, Macharia PM, Alegana VA, English M, et al. Access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015: a geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2018;6(3):e342–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30488-6.

Joseph NK, Macharia PM, Ouma PO, Mumo J, Jalang’o R, Wagacha PW, et al. Spatial access inequities and childhood immunisation uptake in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09486-8.

Ray N, Ebener S. AccessMod 3.0: Computing geographic coverage and accessibility to health care services using anisotropic movement of patients. Int J Health Geographics. 2008;7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-7-63.

Maina J, Ouma PO, Macharia PM, Alegana VA, Mitto B, Fall IS, et al. A spatial database of health facilities managed by the public health sector in sub Saharan Africa. Sci Data. 2019;6(1):1–8.

Alegana VA, Maina J, Ouma PO, Macharia PM, Wright J, Atkinson PM, et al. National and sub-national variation in patterns of febrile case management in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07536-9.

Moturi AK, Suiyanka L, Mumo E, Snow RW, Okiro EA, Macharia PM. Geographic accessibility to public and private health facilities in Kenya in 2021: An updated geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022;10:1002975. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1002975.

Wei T, Simko V, Levy M, Xie Y, Jin Y, Zemla J. R package “corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. Statistician. 2017;56.

Stanton MC, Diggle PJ. Geostatistical analysis of binomial data: Generalised linear or transformed Gaussian modelling? Environmetrics. 2013;24(3). https://doi.org/10.1002/env.2205.

Rue H, Martino S, Chopin N. Approximate Bayesian inference for latent Gaussian models by using integrated nested Laplace approximations. J Royal Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2009;71(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2008.00700.x.

Lindgren F, Rue H, Lindström J. An explicit link between gaussian fields and gaussian markov random fields: The stochastic partial differential equation approach. J Royal Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 2011;73(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2011.00777.x.

Macharia PM, Giorgi E, Noor AM, Waqo E, Kiptui R, Okiro EA, et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of Plasmodium falciparum prevalence to understand the past and chart the future of malaria control in Kenya. Malar J. 2018;17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2489-9.

Giorgi E, Osman AA, Hassan AH, Ali AA, Ibrahim F, Amran JGH, et al. Using non-exceedance probabilities of policy-relevant malaria prevalence thresholds to identify areas of low transmission in Somalia. Malar J. 2018;17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-018-2238-0.

Tejedor-Garavito N, Carioli A, Wigley A, Tatem AJ. 2000, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2017 and 2020 estimates of numbers of pregnancies per grid square, with national totals adjusted to match national estimates on numbers of pregnancies made by the Guttmacher Institute, Version 3. 2021. Southampton; doi: doi:https://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00719

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna; 2021. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

Weeramanthri TS, Dawkins HJS, Baynam G, Bellgard M, Gudes O, Semmens JB. Editorial: Precision Public Health. Front Public Health. 2018;6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00121.

Lang’At E, Mwanri L, Temmerman M. Effects of implementing free maternity service policy in Kenya: An interrupted time series analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4462-x.

Atuoye KN, Barnes E, Lee M, Zhang LZ. Maternal health services utilisation among primigravidas in Uganda: What did the MDGs deliver? Global Health. 2020;16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00570-7.

Njuguna J, Kamau N, Muruka C. Impact of free delivery policy on utilization of maternal health services in county referral hospitals in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2376-z.

Orangi S, Kairu A, Malla L, Ondera J, Mbuthia B, Ravishankar N, et al. Impact of free maternity policies in Kenya: An interrupted time-series analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(6). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003649.

Orangi S, Kairu A, Ondera J, Mbuthia B, Koduah A, Oyugi B, et al. Examining the implementation of the Linda Mama free maternity program in Kenya. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2021;36(6). https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3298.

Bua J, Paina L, Kiracho EE. Lessons learnt during the process of setup and implementation of the voucher scheme in Eastern Uganda: A mixed methods study. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0292-3.

Waiswa P, Peterson SS, Namazzi G, Ekirapa EK, Naikoba S, Byaruhanga R, et al. The Uganda Newborn Study (UNEST): An effectiveness study on improving newborn health and survival in rural Uganda through a community-based intervention linked to health facilities - study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-13-213.

Paina L, Namazzi G, Tetui M, Mayora C, Kananura RM, Kiwanuka SN, et al. Applying the model of diffusion of innovations to understand facilitators for the implementation of maternal and neonatal health programmes in rural Uganda. Global Health. 2019;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0483-9.

Borghi J, Ramsey K, Kuwawenaruwa A, Baraka J, Patouillard E, Bellows B, et al. Protocol for the evaluation of a free health insurance card scheme for poor pregnant women in Mbeya region in Tanzania: A controlled-before and after study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0905-1.

Wong KLM, Brady OJ, Campbell OMR, Banke-Thomas A, Benova L. Too poor or too far? Partitioning the variability of hospital-based childbirth by poverty and travel time in Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria and Tanzania. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-1123-y.

Macharia PM, Joseph NK, Sartorius B, Snow RW, Okiro EA. Subnational estimates of factors associated with under-five mortality in Kenya: A spatio-temporal analysis, 1993–2014. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004544.

Macharia PM, Mumo E, Okiro EA. Modelling geographical accessibility to urban centres in Kenya in 2019. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251624.

Sserwanjaid Q, Mukunya D, Nabachenje P, Kemigisa A, Kiondo P, Wandabwa JN, et al. Continuum of care for maternal health in Uganda: A national cross-sectional study; 2022; Available from. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264190.

Development Initiatives. Poverty in Uganda: National and regional data and trends. 2021. [Accessed 25 Mar 2022] Available from: https://devinit.org/resources/poverty-uganda-national-and-regional-data-and-trends/

Kananura RM, Kiwanuka SN, Ekirapa-Kiracho E, Waiswa P. Persisting demand and supply gap for maternal and newborn care in eastern Uganda: a mixed-method cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0402-6.

Aikaeli J, Garcés-Urzainqui D, Mdadila K. Understanding poverty dynamics and vulnerability in Tanzania: 2012–2018. Rev Dev Econ. 2021;25(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/rode.12829.

Konje ET, Magoma TN, Hatfield J, Kuhn S, Sauve RS, Dewey DM. Missed opportunities in antenatal care for improving the health of pregnant women and newborns in Geita district, Northwest Tanzania. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2014-8

Kabia E, Mbau R, Oyando R, Oduor C, Bigogo G, Khagayi S, et al. “We are called the et cetera”: Experiences of the poor with health financing reforms that target them in Kenya. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1006-2.

Masaba BB, Mmusi-Phetoe RM. Free Maternal Health Care Policy in Kenya; Level of Utilization and Barriers. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2020;13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100234.

Arunda MO, Agardh A, Asamoah BO. Determinants of continued maternal care seeking during pregnancy, birth and postnatal and associated neonatal survival outcomes in Kenya and Uganda: analysis of cross-sectional, demographic and health surveys data. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e054136 Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/11/12/e054136.abstract.

Novignon J, Ofori B, Tabiri KG, Pulok MH. Socioeconomic inequalities in maternal health care utilization in Ghana. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1043-x.

Bbaale E. Factors influencing timing and frequency of antenatal care in Uganda. Australas Med J. 2011;4(8). https://doi.org/10.4066/AMJ.2011.729.

Sserwanja Q, Mutisya LM, Musaba MW. Exposure to different types of mass media and timing of antenatal care initiation: insights from the 2016 Uganda Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Women’s Health. 2022;22(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01594-4.

Delzer ME, Kkonde A, McAdams RM. Viewpoints of pregnant mothers and community health workers on antenatal care in Lweza village, Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2 February). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246926.

Tama E, Molyneux S, Waweru E, Tsofa B, Chuma J, Barasa E. Examining the implementation of the free maternity services policy in Kenya: A mixed methods process evaluation. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018;7(7). https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2017.135.

Ekholuenetale M. Prevalence of Eight or More Antenatal Care Contacts: Findings From Multi-Country Nationally Representative Data. Global Pediatric Health. 2021:8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333794X211045822.

Banke-Thomas A, Ayomoh FI, Abejirinde I-OO, Banke-Thomas O, Eboreime EA, Ameh CA. Cost of Utilising Maternal Health Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2020.104.

Kimathi L. Challenges of the devolved health sector in Kenya: Teething problems or systemic contradictions? Africa Dev. 2017;42(1).

Dowhaniuk N. Exploring country-wide equitable government health care facility access in Uganda. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01371-5.

Roed MB, Engebretsen IMS, Mangeni R, Namata I. Women’s experiences of maternal and newborn health care services and support systems in Buikwe District, Uganda: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0261414. Available from. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261414.

Beyond Zero. [Accessed 4 Mar 2022] Available from: https://www.beyondzero.or.ke/about/

Mbonye PN, Ngolobe M. Village health teams, key structures in saving mothers and their babies from preventable deaths. Reaching the most deprived in remote Karamoja. [Accessed 25 Feb 2022] Available from: https://www.unicef.org/uganda/stories/village-health-teams-key-structures-saving-mothers-and-their-babies-preventable-deaths

Ssetaala A, Nabawanuka J, Matovu G, Nakiragga N, Namugga J, Nalubega P, et al. Components of antenatal care received by women in fishing communities on Lake Victoria, Uganda; A cross sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05739-9.

Wambua S, Malla L, Mbevi G, Nwosu A-P, Tuti T, Paton C, et al. The indirect impact of COVID-19 pandemic on inpatient admissions in 204 Kenyan hospitals: An interrupted time series analysis. PLOS Global Public Health. 2021;1(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000029.

Zhang H, Fink G, Cohen J. The impact of health worker absenteeism on patient health care seeking behavior, testing and treatment: A longitudinal analysis in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8 August). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256437.

Burt JF, Ouma J, Lubyayi L, Amone A, Aol L, Sekikubo M, et al. Indirect effects of COVID-19 on maternal, neonatal, child, sexual and reproductive health services in Kampala, Uganda. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(8). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006102.

Scanlon ML, Maldonado LY, Ikemeri JE, Jumah A, Anusu G, Bone JN, et al. A retrospective study of the impact of health worker strikes on maternal and child health care utilization in western Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06939-7.

Waithaka D, Kagwanja N, Nzinga J, Tsofa B, Leli H, Mataza C, et al. Prolonged health worker strikes in Kenya- perspectives and experiences of frontline health managers and local communities in Kilifi County. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-1131-y.

Banke-Thomas A, Semaan A, Amongin D, Babah O, Dioubate N, Kikula A, et al. A mixed-methods study of maternal health care utilisation in six referral hospitals in four sub-Saharan African countries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(2):e008064 Available from: http://gh.bmj.com/content/7/2/e008064.abstract.

Makacha L, Makanga PT, Dube YP, Bone J, Munguambe K, Katageri G, et al. Is the closest health facility the one used in pregnancy care-seeking? A cross-sectional comparative analysis of self-reported and modelled geographical access to maternal care in Mozambique, India and Pakistan. Int J Health Geographics. 2020;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-020-0197-5.

Benova L, Tunçalp Ö, Moran AC, Campbell OMR. Not just a number: examining coverage and content of antenatal care in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health. 2018;3(2) Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/3/2/e000779.

Okiro EA. Estimates of subnational health trends in Kenya. Lancet Global Health. 2019;7:e8–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30516-3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the DHS team, national based agencies that contributed to the success of the survey, the survey enumerators and the women who contributed information about their lives.

Funding

PMM is supported by the Royal Society as a Newton International Fellow (NIF/R1/201418). NKJ is supported through her EPSRC Training Fellowship (number EP/T003677/1) and funds from Prof. Emelda’s Wellcome Trust Intermediate Fellowship (number 201866). LB is funded in part by the Research Foundation – Flanders (FWO) as part of her Senior Postdoctoral Fellowship (number 1234820 N). PMM and NKJ acknowledge the support of the Wellcome Trust to the Kenya Major Overseas Programme (number 203077).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PMM: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Software, Visualization, Validation Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; NJK: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing; GKN and BM: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review and editing; ABT and LB: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review and editing; OJ: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft preparation, Writing – review and editing. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Section A1.

Key indicators for Kenya, Uganda, and mainland Tanzania. SI Fig. 1. Health planning units in Uganda, Kenya, and Mainland Tanzania. SI Table 1. Key indicators for Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. Section A2. Sampling in malaria indicator surveys. SI Table 2. Proportions of missing observations. S1 Section A3. Exploration of the relationship between the prevalence and covariates. S1 Fig. 2. Correlation plot for Kenya. SI Fig. 3. correlation plot for Tanzania. SI Fig. 4. Correlation plot for Uganda. S1 Fig. 5. Relationship between the empirical coverage of ANC4+ and the predictors for Kenya. S1 Fig. 6. Relationship between the empirical coverage of ANC4+ and the predictors for Tanzania. SI Fig. 7. Relationship between the empirical coverage of ANC4+ and the predictors for Uganda. SI Fig. 8. Empirical variogram for Kenya. SI Fig. 9. Empirical variogram for Uganda. SI Fig. 10. Empirical variogram for Tanzania. SI Section A4. Parameter estimation and spatial prediction. SI Fig. 11. Kenya’s triangulated mesh to build the SPDE model. SI Fig. 12. Uganda’s triangulated mesh to build the SPDE model. SI Fig. 13. Tanzania’s triangulated mesh to build SPDE model. SI Section A5. Exceedance probabilities. SI Fig. 14. Exceedance probability for Kenya, Uganda, and mainland Tanzania. SI Section A6. Validating the assumed spatial correlation function. SI Fig. 15. Empirical variogram estimated from the mixed effect model, including the 95% confidence interval band obtained from a simulation from the fitted model in Kenya. SI Fig. 16. Empirical variogram estimated from the mixed effect model, including the 95% confidence interval band obtained from a simulation from the fitted model in Uganda. SI Fig. 17. Empirical variogram estimated from the mixed effect model, including the 95% tolerance band obtained from a simulation from the fitted model in Tanzania. Fig. 18. The absolute number of women with less than 4 ANC visits across health planning units in Uganda, Kenya, and mainland Tanzania. SI section A8. Parameter estimates and corresponding 95% credible interval.

Additional file 2:

District level estimates for ANC4+ across equity stratifiers.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Macharia, P.M., Joseph, N.K., Nalwadda, G.K. et al. Spatial variation and inequities in antenatal care coverage in Kenya, Uganda and mainland Tanzania using model-based geostatistics: a socioeconomic and geographical accessibility lens. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 908 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05238-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-05238-1