Abstract

Background

Unintended pregnancies (UPs) are a global health problem as they contribute to adverse maternal and offspring outcomes, which underscores the need for prevention. As psychiatric vulnerability has previously been linked to sexual risk behavior, planning capacities and compliance with contraception methods, we aim to explore whether it is a risk factor for UPs.

Methods

Electronic databases were searched in November 2020. All articles in English language with data on women with age ≥ 18 with a psychiatric diagnosis at time of conception and reported pregnancy intention were included, irrespective of obstetric outcome (fetal loss, livebirth, or abortion). Studies on women with intellectual disabilities were excluded. We used the National Institutes of Health tool for assessment of bias in individual studies and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation method for assessment of quality of the primary outcome.

Findings

Eleven studies reporting on psychiatric vulnerability and UPs were included. The participants of these studies were diagnosed with mood, anxiety, psychotic, substance use, conduct and eating disorders. The studies that have been conducted show that women with a psychiatric vulnerability (n = 2650) have an overall higher risk of UPs compared to women without a psychiatric vulnerability (n = 16,031) (OR 1.34, CI 1.08–1.67) and an overall weighed prevalence of UPs of 65% (CI 0.43–0.82) (n = 3881).

Interpretation

Studies conducted on psychiatric vulnerability and UPs are sparse and many (common) psychiatric vulnerabilities have not yet been studied in relation to UPs. The quality of the included studies was rated fair to poor due to difficulties with measuring the outcome pregnancy intention (use of various methods of assessment and use of retrospective study designs with risk of bias) and absence of a control group in most of the studies. The findings suggest an increased risk of UPs in women with psychiatric vulnerability. As UPs have important consequences for mother and child, discussing family planning in women with psychiatric vulnerabilities is of utmost importance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Unintended pregnancies (UPs) are a global health problem of large scale. Every year, 120 million UPs (accounting for 48% of all pregnancies) occur worldwide, although UPs rates differ amongst geographic regions with generally higher rates of UPs in developing countries [1]. UPs could either be mistimed (wanted but not planned at this specific moment in life) or unwanted (not intended at this point nor in the future). UPs are known to have serious consequences as they contribute to adverse maternal and offspring outcomes [2], such as antenatal and chronic depression in mothers [3,4,5,6,7], adverse birth outcomes [2, 8], lower rates of breastfeeding [9, 10], lower quality of mother- and father child interaction [11], and higher prevalence of externalizing problems in puberty in offspring [12]. In addition to adverse effects of unintended births, UPs can also lead to abortions, which are often performed unsafely and account for 7.9% of all maternal deaths worldwide [1, 13]. To prevent UPs, studies investigating risk factors are of utmost importance. Although several risk factors have been identified, such as young maternal age, low educational level (of both parents), and being unmarried [14,15,16,17,18], other potential risk factors, such as mental health, are less explored. Studies already demonstrated that in teenage women with psychiatric conditions (depression, psychosis, and personality disorders) UPs are common [19], but if this also applies for adult women is yet unclear. A previous review on (awareness of) reproductive health problems in women with serious mental illness (that included studies up to 2008) described that the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, pregnancy loss and having more lifetime sex partners is high amongst women with psychiatric conditions [20]. However, unwanted pregnancies and abortions in women who previously reported a psychiatric vulnerability were not the focus of this review. It has been suggested that psychiatric vulnerability (a history of psychiatric disorders according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV or 5 and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)-10/11 and/or current psychiatric disorder according to DSM-IV or 5 and ICD-10/11) could influence important factors related to UPs, such as sexual behavior, including victimization of sexual violence [21] or disruption of menstrual cycles due to stress, use of antipsychotic drugs or weight loss in eating disorders [22, 23]. Also, advanced planning capacities, which are required for adequate use of contraceptive methods and family planning, [23, 24] has shown to be diminished in women with psychiatric vulnerability. Thus, we aimed to explore whether psychiatric vulnerability is a risk factor for UPs, by quantifying the presence of UPs amongst adult women with psychiatric vulnerability, in addition to comparing UPs in women with and without psychiatric vulnerability by means of a systematic literature search and meta-analysis.

Methods

A review protocol was developed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [25] and was registered with Prospero (review number CRD42020221072).

Information sources and search strategy

The electronic databases PubMed, Embase/Ovid, PsycINFO, Cochrane and Web of Science/Clarivate Analytics were searched on November 6, 2020 (see Additional file 1 for search strategy) to identify studies reporting the proportions of UPs in adult women with (and without) psychiatric vulnerability via self-report, structured clinical interviews, or diagnosis performed by a professional.

There were no restrictions in publication date applied to the search. Only articles in English language were included. Unpublished studies and abstracts were excluded from the review.

Eligibility criteria

Presence of psychiatric vulnerability at the time of conception was a prerequisite for inclusion. Also, the main outcome, namely UPs that can result in both ongoing pregnancies and elective (induced) abortions, had to be reported. Studies that evaluated pregnancy planning (planned and unplanned pregnancies) instead of pregnancy intention were also included. Studies with or without ‘control groups’ (women without a psychiatric vulnerability) were included.

Study selection

Studies were eligible for inclusion if the following criteria were met:

-

study participants were women who had become pregnant.

-

participants were adults: 1) age ≥ 18 years, 2) 95% of the participants was ≥18 years old (mean age − 2 standard deviations ≥18), or 3) a subgroup analysis in women ≥18 years was performed.

-

participants had a psychiatric vulnerability (a history of psychiatric disorders according to DSM-IV or 5 and ICD-10/11 and/or current psychiatric disorder according to DSM-IV or 5 and ICD-10/11) via self-report, structured clinical interviews, or diagnosis performed by a professional.

-

studies evaluated proportions of unintended, mistimed, unwanted or unplanned pregnancies resulting in ongoing pregnancies or induced abortions.

When articles reported unclear in- and exclusion criteria, the authors were contacted to provide this information. In addition, we contacted authors of studies from 01 to 01-2000 and more recent and invited them to share data in case this was not available for the meta-analysis in published papers.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (NS and NR) screened the identified articles separately based on title and abstract using Rayyan QCRI software [26]. Subsequently, full text screening was performed independently by NS and NR to see whether the articles fulfilled all inclusion and exclusion criteria. If no agreement was reached, a third reviewer (BB) resolved conflicts. Data synthesis was performed by use of a custom-made form that entailed all information necessary to compare studies. Variables analyzed in this review were authors and year of publication, presence and type of psychiatric disorder, presence and type of comparison group (if available), study design, sample size, age of participants, timing and tool used to measure UPs and prevalence of UPs in the study population. NS conducted the full data extraction and NR verified this.

Assessment of risk of bias

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) [27] method was used to assess quality of the outcome UP. The National Institute of Health (NIH) tools for quality assessment [28] were used to assess the risk of bias in individual studies according to study type. Studies were qualified as ‘good’, ‘fair’ or ‘poor’ considering the risk of bias in that study for our specific outcome ‘UPs’. Hence, studies were assessed solely on the ability to report data on the outcome of interest in this review. Inconsistency was evaluated according to the following levels of heterogeneity by use of I2 tests: 25% was considered low, 50% moderate and 75% substantial heterogeneity [29]. A cut-off p-value of < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance of the test. Indirectness was based on the ability of the data to relate to UP rates and imprecision was based on the confidence intervals of the presented results. Publication bias was assessed by evaluating a funnel plot for possible asymmetry. Also, we considered the absence of (un) published articles (with negative findings) in this field. The quality assessments were performed by two individual reviewers (NS and NR), and a third reviewer was involved to resolve conflicts (BB).

Procedure for data synthesis

Odds ratios (ORs), relative risks (RRs) and risk differences (RDs) were reported if present. In case of observational studies without comparative designs, percentages and means were reported. A meta-analysis of prevalence of UPs amongst women with psychiatric vulnerability was conducted by use of random effects models with the software programmes OpenMetaAnalyst [30] and Rstudio [31]. An I2 test was performed to investigate heterogeneity of the studies in addition to sensitivity analyses to control for robustness of the findings [29]. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Separate meta-analyses (forest plots) of specific psychiatric disorder groups were performed in case of ≥4 studies per disorder.

Results

Study selection

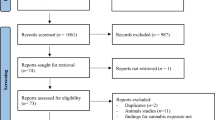

The inclusion process is displayed in Fig. 1. After electronic searches were performed 5429 articles were extracted and consequently transferred to Rayyan QCRI software [26]. After duplicate removal, screening of title and abstract of 3334 articles was conducted. This resulted in full text reading of 58 articles to assess whether inclusion and/or exclusion criteria were met. Based on the eligibility criteria, eleven articles could be included in the qualitative synthesis. Of the eleven articles, eight articles could be included in the meta-analysis on the prevalence of UPs amongst women with psychiatric vulnerability (Fig. 3) and four studies in the meta-analysis of OR on UPs between women with and without psychiatric vulnerability (Fig. 4).

Study characteristics

The characteristics and results of individual studies are presented in Table 1. An overall sample of 18,681 women with (n = 2650) and without (n = 16,031) psychiatric vulnerability were included. Seven categories of psychiatric disorders are represented in this review: eating disorders [32, 42], mood disorders (depression or bipolar disorder) [33, 38, 44, 47, 49], anxiety disorders [44, 47, 49], trauma-related disorders [44, 49], psychosis and related disorders [33, 35], substance use disorders [40, 46, 49], and conduct disorders [43]. Two studies reported on abortion as an outcome of UPs [35, 43] and the other nine studies on (live) births. All studies were conducted in high income countries. Some of the included studies inquired for pregnancy intention during pregnancy, however these studies varied in timing of assessment [32, 40, 44, 47]. Other studies did not report in which trimester women were asked about pregnancy intention [33, 42, 46, 49]. One prospective cohort study assessed pregnancy intention prior to conception and evaluated the number of positive pregnancy tests over the course of one year [38]. In case a woman (without pregnancy aspirations at baseline) became pregnant within twelve months, the pregnancy was defined unintended. In addition, some studies made use of (validated) tools to assess pregnancy intention, while others only reported the questions that were asked to inquire for pregnancy intention. The interpretation of participants’ responses varied: some studies discriminated between unwanted pregnancies and UPs, other studies solely asked for pregnancy planning or pregnancy intendedness. Most studies investigated UPs in women from all ages (within the reproductive phase of life), although one study included only young women (18–20 years) in particular [38].

Results per subgroup of psychiatric disorder

The results of all individual studies are presented in Table 1.

UPs in women with a psychiatric disorder versus no psychiatric disorder

Three studies compared women with a psychiatric disorder (not specified) to a control group [42, 47, 49]. Tenkku et al. found no difference in OR of UPs between women with and without any psychiatric disorder [49], while both Micali et al. and Takahashi et al. reported higher ORs in women with a psychiatric condition compared to controls [42, 47].

Mood disorders

We found five studies that included women with mood disorders [33, 38, 44, 47, 49]. Hall et al. found similar rates of UPs in young women with and without depressive symptoms in a prospective setting even as Tenkku et al. in cross-sectional analyses [38, 49]. In contrast, Takahashi et al. found a higher OR of UPs in women with mood disorders compared to women without mood disorders [47]. Two studies without control groups reported prevalences of UPs (85% in Green et al. and 46–48.4% in Roca et al.) [33, 44].

Anxiety disorders

Women with various anxiety disorders were included in three studies [44, 47, 49]. Tenkku et al. showed no difference between women with and without anxiety disorder according to DSM-IV (of which most women had a trauma-related disorder) in UPs [49]. However, Takahashi et al. presented an increased OR of UPs in women with anxiety disorders compared to women without anxiety disorders [47]. In the study sample of Roca et al., 40 women with panic disorder, 16 with generalized anxiety disorder, 10 with obsessive-compulsive disorder, three with post-traumatic stress disorder and two with anxiety disorder not otherwise specified were included, of which 33 had UPs (46% of women with any type of anxiety disorder) [44].

Psychosis and related disorders

Women with psychosis and related disorders were investigated in two papers [33, 35]. Green et al. described 85% UPs in 39 women with a risk for postpartum psychotic episode (history of psychotic episode, history of postpartum depression or bipolar disorder) who were in care at a perinatal mental health service during their pregnancy [33]. Gupta et al. compared the incidence of abortions between women with and without schizophrenia in the first year after a previous pregnancy (these pregnancies are referred to as ‘rapid repeat pregnancies’) [35] and found similar rates of induced abortions in both groups.

Substance use disorders

Pregnancy intention was assessed in 1455 women who used substances. UPs were often reported in this group of women (74–100%) [40, 46, 49]. Multi-drug use was reported in one study (Tabi et al.) as aside from opioid use, participants reported the (ab)use of cannabis, cocaine, benzodiazepines, methamphetamine, and alcohol [46]. Tenkku et al. assessed nicotine dependence, alcohol and drug abuse in 484 women [49], of which 74% had UPs. Heil et al. found 86% UPs in 946 pregnant opioid addicted women [40].

Conduct disorders

One study showed higher rates of (lifetime) abortions in women with a history of high CD symptoms at age 15, (≥7 problems based on DSM-III-R) compared to women with low CD symptoms at age 15. After adjusting for multiple social and psychological confounders, the associations between CD symptoms and abortions remained significant [43].

Eating disorders

Assessment of pregnancy intention was performed amongst 927 women with eating disorders in two European studies [32, 42]. In women with anorexia nervosa (AN), OR for UPs were higher than in women without anorexia nervosa, however in women with and without bulimia nervosa (BN), OR for UPs did not differ.

Risk of bias of included studies

Quality of the included studies is displayed in Table 2. The outcome UPs graded with the NIH tool [28] resulted in a fair quality for nine out of eleven studies and poor quality in two out of eleven studies. Degree of author agreement was 84% between two reviewers (NS and NR), consensus was reached with a third reviewer (BB). Additional file 2 displays the grading per item in the NIH tool. Risk of bias was high due to cross-sectional analyses of cohort data. Solely one study assessed pregnancy intention in a prospective manner [38], one other study assessed abortion in a prospective manner [43]. In most studies, time from exposure (psychiatric vulnerability) to outcome (UPs) was not measured and/or reported. In addition, UPs were not measured using validated tools. We found that 8 studies primarily focused on UPs or abortions, while three studies included pregnancy intention as secondary outcome or demographic feature [33, 35, 46]. Most studies considered relevant confounders, although small sample sizes limited ability to perform multiple regression analyses in some studies [44, 46]. Most studies had a sample size of less than 600 women, while two studies had a larger sample size: Micali et al. included 1961 women and Heil et al. included 946 women [40, 42]. A funnel plot (Fig. 2) demonstrates the variety in sample sizes and effect sizes per study.

Data synthesis

A meta-analysis was performed with a random effects model of the eight studies that provided prevalences of UPs amongst 3881 pregnant women (in case studies presented unwanted and unplanned pregnancies instead of UPs, we calculated number of UPs for this meta-analysis) (Fig. 3). We performed a logit transformation of the results, to consider the maximum prevalence of UPs in studies of 100%. Overall, the rate of UPs was 65% (CI 0.43–0.82). Sensitivity analyses were performed and showed that the effect size remained within 95% CI if any of the studies was left out. Moderate heterogeneity was found within the studies as the I2 of 67% displays (p = 0.03) (see Fig. 3). In addition, separate analyses were performed on the four studies that reported OR of UPs comparing a psychiatric vulnerable group to a control group (Fig. 4). One study on women with eating disorders [32] and three studies on women with a variety of psychiatric vulnerabilities (mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders and/or psychosis) [42, 47, 49]. The overall odds of UPs were higher in women with psychiatric vulnerability compared to women without psychiatric vulnerability (OR 1.34, CI 1.08–1.67), n = 18,681.

Conclusions

Principal findings

This systematic review shows that studies on UPs in women with psychiatric vulnerability are sparse, and for many relevant psychiatric disorders (such as personality disorders, autism spectrum disorder and trauma related disorders) the risk for UPs remains unknown. However, the studies that have been conducted suggest that psychiatric vulnerability is a risk factor for UPs: women with a psychiatric vulnerability have an overall higher risk of UPs compared to women without a psychiatric vulnerability (OR 1.34, CI 1.08–1.67) and an overall weighed prevalence of UPs of 65% (CI 0.43–0.82). As most studies have explored UPs leading to (live) births and did not include or explore UPs leading to abortions, it is likely that this overall prevalence of UPs is even underestimated.

Comparison with existing literature

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the relation between psychiatric vulnerability and UPs. Planning capacities, perception of risks related to unprotected intercourse and subsequent ability to prevent UPs by use of contraception, even as compliance with contraception methods could be impaired by decreased cognitive or emotional functioning during active (severe) mental disorders like mood disorders, schizophrenia or related psychotic conditions [23, 38, 51, 52]. Manic symptoms in women with bipolar disorder could lead to impulsivity and hypersexuality, resulting in risky sexual behavior [53]. In eating disorders there are a few other mechanisms that should also be considered: oligomenorrhea is common and can be misinterpreted as a lower risk of pregnancy or even beliefs about infertility, which could subsequently lead to unintended pregnancies in case of unexpected ovulation. Also, oral contraceptives will not provide prevention of UPs in case of (frequent) purging [22, 42]. Moreover, previous data suggest that in women who requested a termination of pregnancy, traumatic experiences such as sexual violence were prevalent, even as depression and anxiety symptoms [54].

Unfortunately, the extent to which women in the studies included in this review were facing active and/or severe psychiatric symptoms at time of conception was not always clearly described. Some authors, like Micali et al., separately analyzed women with symptoms in the year prior to their pregnancy and found they were more prone to UPs than women with a history of psychiatric disorders [42]. Based on available data in our review, we were not able to conclude whether this finding applies to all psychiatric diagnostic categories.

Gaps in literature

Although we included studies covering a variety of psychiatric disorders, we conclude that studies on common psychiatric disorders like personality disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder are lacking. Further studies are needed to investigate UPs in women with these disorders.

Although several studies included women with mood and anxiety disorders, absolute numbers of participants were small. As mood and anxiety disorders are known to be the most prevalent mental disorders, that are almost twice as common in women than in men, it is especially important to understand the role of these disorders in relation to UPs, hence further studies in this field should also be encouraged [55,56,57]. As none of the studies included in this review were conducted in low-income countries our findings may not apply for low-income countries. Several studies have described that UP rates are similarly high or even higher in low-income countries compared to high-income countries [1, 58, 59], and that the adverse effects of UPs in low-income countries are severe [60].

Strengths and limitations

Our review has several strengths. First, the extensive search in electronic databases that included all psychiatric disorders, allowed us to gain insight in various specific psychiatric disorders in relation to UPs in addition to an overview of the overall presence of psychiatric vulnerability in relation to UPs. Moreover, we accepted both ongoing pregnancies and induced abortions as outcomes of UPs as previous studies underscored the importance of identifying abortions in women with psychiatric conditions as elective abortions can be a result of UPs [20, 61].

However, our review also has several limitations. We only included studies that were written in English language which may reduce generalizability, however, peer-reviewed studies in other languages were relatively rare. Also, the studies included in the review had fair to poor quality ratings for the primary outcome, used varying psychiatric disorders as control group within studies, used various methods to assess the outcome pregnancy intention (by live births or abortions), differed in timing of measurement of pregnancy intention (which is key in preventing recall bias [62]), and showed divergent results. Pregnancy intention was only measured with validated tools in a few studies [40, 47, 49], while most studies used a single question which may lack nuance [32, 38, 42, 44], or the way of measuring was not reported at all [33, 46]. Abortion was in one study self-reported and in another based on a large obstetric dataset which included surgical abortion registrations [35, 43]. In addition, important confounders such as age, educational level and environmental influences were considered in varying degrees [18]. In particular partner violence and poor partner relationship were posed as risk factor for UPs previously [63] and in women with psychiatric vulnerability, reproductive coercion appears to be common [64, 65]. Lastly, our meta-analysis was limited to only four studies with comparison groups and the overall low quality of this body of evidence limited our capacity to draw definitive conclusions.

Research recommendations

Ideally, assessment of pregnancy intention is performed 1) by means of a validated tool, and 2) as early in pregnancy as possible. At the same time, prospective settings are time-consuming and might overestimate UP rates since pregnancy intention can change over time [62]. However, prospective designs ensure that psychiatric vulnerability was present before the onset of the UPs, which could give insight in the causality between psychiatric vulnerability and UPS and limit recall bias. Regarding psychiatric vulnerability, we conclude that the onset, duration, and severity of psychiatric vulnerability are important to include, to understand the relation between psychiatric vulnerability and UPs. Last, we recommend that relevant confounders like race, household income, marital status, age, partner relationship, partner violence and reproductive coercion are also taken into account when investigating UPs.

Implications

In conclusion, we have found a high prevalence of UPs in women with psychiatric vulnerability, and an increased risk of UPs in psychiatric vulnerable pregnant women compared to pregnant women without psychiatric vulnerability. Given the known adverse outcomes of UPs for maternal and offspring health, we underline the importance of discussing family planning with all women at reproductive age with psychiatric vulnerability routinely to avoid any harm due to UPs.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study but published previously in studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Abbreviations

- UP:

-

Unintended pregnancy

- DSM:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- ICD:

-

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems

- NIH:

-

National Institute of Health

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

- RRs:

-

Relative risks

- RDs:

-

Risk differences

- AN:

-

Anorexia nervosa

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

References

Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Ganatra B, Moller AB, Tunçalp Ö, Beavin C, et al. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990-2019. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1152–61.

Hall JA, Benton L, Copas A, Stephenson J. Pregnancy intention and pregnancy outcome: systematic review and Meta-analysis. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(3):670–704.

Abajobir AA, Maravilla JC, Alati R, Najman JM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between unintended pregnancy and perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2016;192:56–63.

Bunevicius R, Kusminskas L, Bunevicius A, Nadisauskiene RJ, Jureniene K, Pop VJ. Psychosocial risk factors for depression during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(5):599–605.

Fellenzer JL, Cibula DA. Intendedness of pregnancy and other predictive factors for symptoms of prenatal depression in a population-based study. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(10):2426–36.

Martini J, Petzoldt J, Einsle F, Beesdo-Baum K, Höfler M, Wittchen HU. Risk factors and course patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders during pregnancy and after delivery: a prospective-longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2015;175:385–95.

Biaggi A, Conroy S, Pawlby S, Pariante CM. Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:62–77.

Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, Frick C. Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(2):205–16.

Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79(3):194–8.

Lindberg L, Maddow-Zimet I, Kost K, Lincoln A. Pregnancy intentions and maternal and child health: an analysis of longitudinal data in Oklahoma. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(5):1087–96.

Nelson JA, O'Brien M. Does an unplanned pregnancy have long-term implications for mother-child relationships? J Fam Issues. 2012;33(4):506–26.

Hayatbakhsh MR, Najman JM, Khatun M, Al Mamun A, Bor W, Clavarino A. A longitudinal study of child mental health and problem behaviours at 14 years of age following unplanned pregnancy. Psychiatry Res. 2011;185(1–2):200–4.

Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323–33.

Pulley L, Klerman LV, Tang H, Baker BA. The extent of pregnancy mistiming and its association with maternal characteristics and behaviors and pregnancy outcomes. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34(4):206–11.

Beck LF, Morrow B, Lipscomb LE, Johnson CH, Gaffield ME, Rogers M, et al. Prevalence of selected maternal behaviors and experiences, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system (PRAMS), 1999. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2002;51(2):1–27.

Besculides M, Laraque F. Unintended pregnancy among the urban poor. J Urban Health. 2004;81(3):340–8.

de La Rochebrochard E, Joshi H. Children born after unplanned pregnancies and cognitive development at 3 years: social differentials in the United Kingdom millennium cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(6):910–20.

Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, Dawson BS. Teenagers in the United States: sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing. Vital Health Stat 23. 2002;2004(24):1–48.

Maravilla JC, Betts KS, Cruz CCE, Alati R. Factors influencing repeated teenage pregnancy: a review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(5):527–545.e531.

Matevosyan NR. Reproductive health in women with serious mental illnesses: a review. Sex Disabil. 2009;27:109–18.

Taylor CL, Stewart R, Ogden J, Broadbent M, Pasupathy D, Howard LM. The characteristics and health needs of pregnant women with schizophrenia compared with bipolar disorder and affective psychoses. BMC Psychiatry. 2015;15:88.

Bulik CM, Hoffman ER, Von Holle A, Torgersen L, Stoltenberg C, Reichborn-Kjennerud T. Unplanned pregnancy in women with anorexia nervosa. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1136–40.

Seeman MV, Ross R. Prescribing contraceptives for women with schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Pract. 2011;17(4):258–69.

Callegari LS, Zhao X, Nelson KM, Borrero S. Contraceptive adherence among women veterans with mental illness and substance use disorder. Contraception. 2015;91(5):386–92.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. 2013.

National Institutes of Health: Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2014.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Wallace BC, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, Lau J, Trow P, Schmid CH. Closing the gap between methodologists and end-users: R as a computational back-end. Journal of Statistical Software. 2012.

RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC. 2020. http://www.rstudio.com/.

Easter A, Treasure J, Micali N. Fertility and prenatal attitudes towards pregnancy in women with eating disorders: results from the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. BJOG. 2011;118(12):1491–8.

Green L, Elliott S, Anwar L, Best E, Tero M, Sarkar A, et al. An audit of pregnant women with severe mental illness referred during the first 2 years of a new perinatal mental health service. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(2):149–58.

Elliott S, Ross-Davie M, Sarkar A, Green L. Detection and initial assessment of mental disorder; 2007.

Gupta R, Brown HK, Barker LC, Dennis CL, Vigod SN. Rapid repeat pregnancy in women with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2019;212:86–91.

Kurdyak P, Lin E, Green D, Vigod S. Validation of a population-based algorithm to detect chronic psychotic illness. Can J Psychiatr. 2015;60(8):362–8.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Important Notes Regarding Coverage. 2014.

Hall KS, Kusunoki Y, Gatny H, Barber J. The risk of unintended pregnancy among young women with mental health symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 2014;100:62–71.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977.

Heil SH, Jones HE, Arria A, Kaltenbach K, Coyle M, Fischer G, et al. Unintended pregnancy in opioid-abusing women. J Subst Abus Treat. 2011;40(2):199–202.

Adams MM, Shulman HB, Bruce C, Hogue C, Brogan D. The pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system: design, questionnaire, data collection and response rates. PRAMS Working Group. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1991;5(3):333–46.

Micali N, dos-Santos-Silva I, De Stavola B, Steenweg-de Graaff J, Steenweg-de Graaf J, Jaddoe V, et al. Fertility treatment, twin births, and unplanned pregnancies in women with eating disorders: findings from a population-based birth cohort. BJOG. 2014;121(4):408–16.

Pedersen W, Mastekaasa A. Conduct disorder symptoms and subsequent pregnancy, child-birth and abortion: a population-based longitudinal study of adolescents. J Adolesc. 2011;34(5):1025–33.

Roca A, Imaz ML, Torres A, Plaza A, Subirà S, Valdés M, et al. Unplanned pregnancy and discontinuation of SSRIs in pregnant women with previously treated affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(3):807–13.

First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition; 2002.

Tabi S, Heitner SA, Shivale S, Minchenberg S, Faraone SV, Johnson B. Opioid addiction/pregnancy and neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS): a preliminary open-label study of buprenorphine maintenance and drug use targeted psychotherapy (DUST) on cessation of addictive drug use. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:563409.

Takahashi S, Tsuchiya KJ, Matsumoto K, Suzuki K, Mori N, Takei N, et al. Psychosocial determinants of mistimed and unwanted pregnancy: the Hamamatsu birth cohort (HBC) study. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):947–55.

Abma JC, Chandra A, Mosher WD, Peterson LS, Piccinino LJ. Fertility, family planning, and women's health: new data from the 1995 National Survey of family growth. Vital Health Stat. 1997;23(19):1–114.

Tenkku LE, Flick LH, Homan S, Loveland Cook CA, Campbell C, McSweeney M. Psychiatric disorders among low-income women and unintended pregnancies. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19(5):313–24.

Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. The diagnostic interview schedule, Version IV. 1995; Chapter 1: HISTORY AND SCOPE OF THE DIS

Yuen KS, Lee TM. Could mood state affect risk-taking decisions? J Affect Disord. 2003;75(1):11–8.

Steinberg JR, Rubin LR. Psychological aspects of contraception, unintended pregnancy, and abortion. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2014;1(1):239–47.

Obo CS, Sori LM, Abegaz TM, Molla BT. Risky sexual behavior and associated factors among patients with bipolar disorders in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):313.

Tinglöf S, Högberg U, Lundell IW, Svanberg AS. Exposure to violence among women with unwanted pregnancies and the association with post-traumatic stress disorder, symptoms of anxiety and depression. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(2):50–3.

Gelaye B, Rondon MB, Araya R, Williams MA. Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(10):973–82.

Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210(5):315–23.

Grigoriadis S, Graves L, Peer M, Mamisashvili L, Tomlinson G, Vigod SN, Dennis CL, Steiner M, Brown C, Cheung A, Dawson H, Rector NA, Guenette M, Richter M. Maternal anxiety during pregnancy and the association with adverse perinatal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(5).

Darroch JE, Woog V, Bankole A, Ashford LS. Adding it up: costs and benefits of meeting contraceptive needs of adolescents. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2016.

du Toit E, Jordaan E, Niehaus D, Koen L, Leppanen J. Risk factors for unplanned pregnancy in women with mental illness living in a developing country. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21(3):323–31.

Singh A, Chalasani S, Koenig MA, Mahapatra B. The consequences of unintended births for maternal and child health in India. Popul Stud (Camb). 2012;66(3):223–39.

Health TNCCfM. Induced abortion and mental health. A systematic review of the mental health outcomes of induced abortion, including their prevalence and associated factors. London: UK Academy of Medical Royal Colleges; 2011.

Gariepy AM, Lundsberg LS, Miller D, Stanwood NL, Yonkers KA. Are pregnancy planning and pregnancy timing associated with maternal psychiatric illness, psychological distress and support during pregnancy? J Affect Disord. 2016;205:87–94.

Miller E, Silverman JG. Reproductive coercion and partner violence: implications for clinical assessment of unintended pregnancy. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2010;5(5):511–5.

Karmaliani R, Asad N, Bann CM, Moss N, Mcclure EM, Pasha O, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression and associated factors among pregnant women of Hyderabad, Pakistan. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2009;55(5):414–24.

Miller LJ, Finnerty M. Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47(5):502–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This review is financially supported by OLVG, Dept. of Psychiatry and Medical Psychology, Amsterdam, Netherlands. This review is conducted in preparation for a study grant, received by ZonMw (554002007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB performed electronic searches and helped design the study methods. NS and NR performed article screening, article selection, and analysis of data. NS wrote the first draft of the manuscript with input from NR, AB, JL, OH and BB who all contributed to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

OH received consultation fee from Lundbeck. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy electronic database.

Additional file 2.

Quality assessment of included studies according to Quality assessment tools by National Institutes of Health (2014).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schonewille, N.N., Rijkers, N., Berenschot, A. et al. Psychiatric vulnerability and the risk for unintended pregnancies, a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04452-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04452-1