Abstract

Background

Over half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, and 18% result in termination of pregnancy (TOP). Some women seek TOP, but ultimately continue their pregnancy. Data are limited about their utilization of prenatal care and their perinatal outcomes. Our primary outcome was to investigate differences in guideline-based prenatal care utilization in women who consider but do not have an abortion.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of patients having obstetrical dating ultrasound (US) from 2011–2018 at a single academic medical center that offers TOP. Contemplators completed US with intention of TOP but instead continued the pregnancy to live birth. A 2:1 group of non-contemplators completed US and continued to live birth. A prenatal care utilization scoring system was used to compare groups. Secondary outcomes investigated differences in adverse pregnancy outcomes and postpartum care.

Results

There were 94 contemplators and 183 non-contemplators. Inadequate prenatal care utilization initially was more common in contemplators than non-contemplators (62.8% vs 85.8%, p < 0.01) but was not significant after adjustment (aOR 1.0, 95% CI 0.40 – 2.56). There were no differences in adverse obstetric or neonatal outcomes. Contemplators were significantly more likely to have a postpartum contraceptive method (PPCM) upon hospital discharge (aOR 4.8, 95% CI 1.16 – 20.0) and significantly more likely to use a highly-effective PPCM (aOR 6.4, 95% CI 2.34 – 17.4).

Conclusions

Reversal of intention for TOP is not associated with differences in prenatal care utilization, but is associated with increased uptake of postpartum contraceptive method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Excluding spontaneous abortions, 18.4% of pregnancies in the United States in 2017 ended in therapeutic abortion [1]. While abortions are common and legal in the US, there are still many barriers that pregnant people face in accessing abortion care, including lack of insurance coverage, not knowing how to obtain care, inability to afford or coordinate transportation, missed wages, misinformation or delays in access arising from crisis pregnancy centers, and policy-related barriers restricting access [2,3,4,5]. Between 7.2% and 11% of pregnant people considering termination ultimately continue their pregnancies [6, 7]. This number includes pregnant people facing policy-related financial or logistical barriers to accessing abortion care, 2% of pregnant people who are denied care due to having a gestational age beyond their clinic’s limit (turnaways) and 2–8% of pregnant people who decide not to get an abortion due to changes in their own personal decision-making [4, 6,7,8].

It cannot be assumed that women who initially consider or seek abortion services have unplanned pregnancies [9], though there are similarities and overlap between these populations. Pregnancy intendedness has been shown to predict pregnancy-related behaviors. Studies of people with unintended pregnancies report they are more likely to present at later gestational ages for prenatal care and are more likely to have fewer antenatal visits compared to those with planned pregnancies [10,11,12,13,14].

There is a small but expanding body of literature on the subpopulation of pregnant people who consider abortion, but ultimately continue with pregnancy. Most of these studies investigate the experiences of turnaways, including effects on mental health, educational attainment, poverty, neonatal outcomes, and subsequent pregnancy outcomes [7, 15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, there are few data published on prenatal care utilization in this subgroup of pregnant people during their ongoing pregnancy. Studies have reported initiation of prenatal care at later gestational ages [22], though some authors report that change in decision-making towards abortion is protective [23]. As compared to those who enter prenatal care without considering abortion, these people have considerably increased health and social service needs which can affect prenatal care utilization [24].

This retrospective observational study aims to fill a gap in research on prenatal care utilization by pregnant people who consider termination, but whose pregnancies end in live birth. A comparison of completeness of guideline-based prenatal care between abortion contemplators and non-contemplators was the primary outcome. Secondary measures including obstetric and neonatal outcomes, postpartum contraception usage and utilization of postpartum care were also compared.

Methods

Study design and setting

This is a retrospective cohort study. All patients received obstetric care at a single tertiary-care medical center in New York State that provides abortion services up to 24 weeks’ gestation of pregnancy for a large geographic catchment area. Data were collected from patients who had a live birth from January 1, 2011 to July 31, 2018.

The exposed group were patients contemplating a termination of pregnancy (TOP) but ultimately continuing on to a live birth due to reversal of decision for TOP for any reason, including late gestational age at presentation. The non-exposed group were patients during the same period who had not contemplated TOP and continued on to a live birth. The primary outcome of interest was difference in prenatal care utilization between groups. Secondary outcomes included differences in individual measures of prenatal care utilization, multiple adverse obstetrical and neonatal outcomes and postpartum contraception and care utilization between groups. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for reporting observational studies were used in study design and manuscript preparation [25]. The study was approved by the lead author’s Institutional Review Board at University of Rochester Medical Center.

Patient selection

Eligible patients were identified by searching the local ultrasound database (AS-OBGYN, AS Software Inc, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA) for patients undergoing obstetric ultrasound for pregnancy confirmation and dating during relevant dates. “Contemplators” were identified using combined results of database search for billing codes for TOP and for sonographer descriptive comments (“TOP”, “abortion”) to capture the largest number of eligible subjects. “Non-contemplators” were identified as contemporary patients without these billing codes or descriptive comments. Patients were ineligible if they underwent termination of pregnancy, experienced first trimester pregnancy loss/ectopic pregnancy or previable stillbirth, or had incomplete prenatal care and delivery records available for review. Patients were included if they were age 13–55 with single or multiple gestations.

To decrease misclassification bias, further eligibility was then assessed through linkage of individual patient medical record number from the AS-OBGYN database to the local electronic medical record (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI, USA) to confirm the ultrasound was performed in the setting of a desired termination (contemplators) or in the absence of desire for termination (non-contemplators) and that the same pregnancy was continued on to live birth.

Non-contemplators were matched to contemplators in approximately a 2:1 ratio. All eligible contemplators were included. Non-contemplators were selected as a convenience sample of patients obtaining a dating ultrasound during the same time frame.

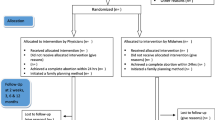

A flow diagram demonstrating subject eligibility and selection is shown in additional Fig. 1.

Variables of interest

Data for all variables were collected from the ultrasound database, electronic medical record and New York State Birth Certificate and Statewide Perinatal Data System (NYS-BC/SPDS). Accuracy of data abstraction was confirmed by random review by a senior study team member (M.T.).

Demographic information

Demographic information to characterize the two study groups was collected. The demographic variable “low educational attainment” was defined as achieving a high school diploma/GED or less. The demographic variable “prenatal depression” was assessed through self-reported response to question in NYS-BC/SPDS record asking “during pregnancy, would you say that you were: 1) not depressed at all, 2) a little depressed, 3) moderately depressed, 4) very depressed, 5) very depressed and had to get help” with answer choices 2–5 considered positive for presence of prenatal depression.

Prenatal Care Utilization Score

Difference in guideline-based prenatal care utilization between groups was determined using a prenatal care utilization scoring system developed for this study. Variables included in the scoring system and their assigned point values are outlined in Fig. 1. Prenatal care was considered adequate when 16 or more points were achieved out of a total of 21 possible points, equating to ~ 75% completion.

Because of prior publications reporting that unintended pregnancy is correlated with late presentation to prenatal care and fewer antenatal visits, a sub-analysis was planned by removing two variables (“% of recommended prenatal visits received” and “first appointment by 12 weeks”) yielding a maximum score of 15. A score \(\geq\) 11 points/15 points (~ 75% completion) was considered inadequate prenatal care.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary aims of this study were to compare individual measures of guideline-based prenatal care utilization, as well as obstetric and neonatal outcomes, between contemplator and non-contemplator groups.

Another secondary aim was also to compare postpartum contraception intention between contemplator and non-contemplator groups. Patients were classified as having a postpartum contraception intention if a specific contraceptive method was documented in the electronic medical record prior to discharge from the hospital admission related to the delivery. Type of immediate postpartum contraception utilized was compared between groups and was stratified into highly effective (long-acting reversible contraceptive placed or depo-provera administered prior to discharge, permanent sterilization, partner vasectomy) or all other methods.

Postpartum care utilization, including presentation to postpartum care visit and rates of postpartum depression screening (by Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale) and were also compared between groups.

Statistical analyses

Demographic variables were compared between contemplator and non-contemplator groups using Fisher’s exact tests and Chi-square tests. Distribution of continuous data was established using the Shapiro–Wilk test followed by Mann–Whitney U test for non-parametric data or Student’s t-test for parametric data. The primary outcome of interest, prenatal care utilization score, was compared between contemplators and non-contemplators using chi-square tests or Mann–Whitney-U tests. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the odds of having a total prenatal care utilization score ≥ 16 as a function of contemplators versus non-contemplators after adjusting for potential confounding variables. Results were calculated as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The data contained at least ten events for each variable entered into the logistic regression model [26]. Confounding variables were identified as maternal demographic variables with significant differences (P < 0.05) in the above bivariate analyses and included race, age, insurance type, education, prior termination, tobacco use in pregnancy, substance use in pregnancy, depression in pregnancy, STI in pregnancy, and gestational age at presentation to prenatal care. Similar analyses were performed to examine all secondary outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 27.0). Results were considered significant at two-sided P value < 0.05.

Results

Demographics

Data were collected on 94 contemplators and 183 non-contemplators, for a total of 277 participants. Statistically significant differences were noted between contemplators and non-contemplators in several maternal characteristics (see Table 1).

Prenatal Care Utilization Score

The median score for contemplators was 17 (IQR 15–19) versus 18 (IQR 16–19) for non-contemplators (P < 0.01). A total of 62.8% of contemplators received a score of at least 16 points/21 possible points (~ 75% completion) on the guideline-based prenatal care utilization score, compared to 85.8% of non-contemplators (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.16 – 0.50). Calculated retrospective power of this observed effect was 98% at alpha = 0.05. However this difference was no longer significant after adjusting for differences in maternal characteristics (aOR 1.0, 95% CI 0.40 – 2.56) (Table 2).

In the sub-analysis (removing “% of recommended prenatal visits received” and “first appointment by 12 weeks” from the scoring system), the median score for contemplators was 11 (IQR 9–12) and for non-contemplators was 11 (IQR 10–12), P = 0.11. There was no difference between groups in the frequency of achieving a ~ 75% completion rate/score of ≥11 (contemplators 52.1% versus non-contemplators 60.1%, P = 0.20).

Individual measures of prenatal care utilization

Contemplators were significantly less likely to present for prenatal care by 12 weeks gestation (contemplators 21.3% versus non-contemplators 82.5%, aOR 0.3, 95% CI 0.13 – 0.79). Non-contemplators were significantly less likely to receive Tdap immunization (contemplators 80.9% versus non-contemplators 60.1%, p < 0.01; aOR 7.8, 95% CI 2.53 – 23.8) (Table 3). After adjusting for confounding factors, there were no differences between groups in individual measures of prenatal care utilization (Fig. 2).

Obstetric and neonatal outcome variables

When adjusted for maternal demographic characteristics, there were no significant differences in odds of having obstetric or neonatal morbidity between contemplator and non-contemplator groups (Table 4, Fig. 3).

Postpartum care utilization

Contemplators were significantly more likely to have immediate uptake of postpartum contraceptive plan prior to hospital discharge (contemplators 92.5% versus non-contemplators 79.4%; aOR 4.8, 95% CI 1.16 – 20.0) and to utilize a highly effective method upon discharge including permanent sterilization, long-acting reversible contraception, or administration of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (contemplators 64.5% versus non-contemplators 79.4%; aOR 6.4, 95% C.I 2.34 – 17.4) (Table 5, Fig. 4).

Non-contemplators were significantly more likely to attend a postpartum visit (contemplators 72.9% versus non-contemplators 58.8%, P < 0.01) though this did not remain significant after adjusting for differences in maternal demographic characteristics between groups (Table 5, Fig. 4).

Discussion

A guideline-based prenatal care utilization scoring system developed for this study found that women contemplating pregnancy termination but ultimately continuing on to live birth initially appeared less likely to achieve ~ 75% completion of recommended prenatal care parameters than those who did not contemplate pregnancy termination, but this was not significant after adjustment. The strongest confounding factor in the adjusted regression was gestational age at presentation to prenatal care.

The prenatal care utilization scoring system did include variables related to timing of entry into prenatal care (“first prenatal care visit by 12 weeks” and “total number of prenatal care visits”). These time-based variables were included because authors were interested to know how prenatal care differed overall in contemplators as compared to the baseline population. However, it is well established in the literature that women with unplanned, mistimed, or unintended pregnancies present to prenatal care at a later gestational age and have fewer antenatal visits compared to those with planned pregnancies [10, 12, 23]. This was also demonstrated in the current study, where the adjusted odds of presenting to prenatal care by 12 weeks was 60% lower in contemplators compared to non-contemplators. Given this, a sub-analysis was performed removing these time-based variables from the prenatal care utilization scoring system to better understand how the quality of prenatal care delivered across different time frames might differ between groups. In the adjusted sub-analysis, there was no difference between groups in prenatal care utilization. These results demonstrate that although many women contemplating pregnancy termination present to prenatal care at a later gestational age, it appears they do “catch up” to the baseline population in achieving the objective components of adequate prenatal care. This is similar to what has been reported regarding prenatal care utilization among women with unintended pregnancies [27]. In addition, they do not experience increased rates of obstetric or neonatal morbidity, though the study is underpowered to demonstrate significant differences in these secondary outcomes.

Studies report that abortion turnaways have an increase in child-birth related morbidity and mortality as compared to those who are provided with abortions [28]. Although we did not detect any differences in the short-term, delivery-related maternal and neonatal morbidities between groups, we were unable to examine long-term outcomes in this study. Delayed maternal morbidity in parenting turnaways includes higher rates of socioeconomic hardship, worsening of self-reported health measures, lower educational attainment and lower rates of aspirational life plans [29,30,31]. Children born to parenting turnaways have higher rates of poor maternal bonding, lower childhood development scores, and are more likely to live below the poverty line [32, 33]. More research in this area is essential to better understand if there are other differences in prenatal care quality or delivery in women who consider but do not have an abortion for any reason, and how this may affect long-term outcomes in women, their children, and their families.

An interesting finding of the current study was that patients in the contemplator group had a significantly increased odds of using immediate post-partum contraception upon hospital discharge from their delivery admission and of using a highly-effective method of postpartum contraception. This persisted after adjusting for potential confounding variables and was present despite there being no difference between groups in rates of documented antepartum contraceptive counseling. Although the content of the antepartum contraceptive counseling is unknown in this case, these results suggest that the experiences of women who consider but do not complete an abortion is associated with their postpartum contraceptive uptake patterns. There were no differences between groups in adjusted rates of presentation to postpartum visit, which is consistent with other authors findings in this same population of women [23].

There are a number of limitations to the current study. The retrospective observational design introduces the possibility of bias related to inaccurate or incomplete record keeping. Certain prenatal care variables (in particular –immunization status for Tdap and Influenza) were not consistently documented by all providers in prenatal care records. An additional limitation is the possibility that some patients in the non-contemplator group did initially seek termination of pregnancy at an outside facility for which records were not available to the study team or may have contemplated TOP without pursuing an ultrasound related to that purpose. There are likely to be undetected differences in prenatal care utilization in subgroups of our study population based on individual reasons for not obtaining abortion (change in decision-making versus facing logistical, financial, or policy barriers to accessing abortion services), but these could not be determined using our retrospective design and would be better investigated by a future prospective survey and structured interview methodology.

Conclusion

The current study recognizes that women considering TOP who ultimately continue the pregnancy to live birth often present later to prenatal care. Despite this, they still receive adequate guideline-based prenatal care as compared to women not considering pregnancy termination. Immediate uptake of postpartum contraceptive method and use of highly effective postpartum contraceptive methods was also higher in women considering but not completing abortion. Further research is necessary to better understand how prenatal care utilization and pregnancy outcomes are affected by the specific factors leading to women to consider but not complete abortions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Mendeley Data repository available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/r28gx9gzfr/1.

Abbreviations

- TOP:

-

Termination of pregnancy

- NYS-BC/SPDS:

-

New York State Birth Certificate and Statewide Perinatal Data System

- GED:

-

General Educational Development Test

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infection

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- TDap:

-

Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis Immunization

References

Jones R, Witwer E, Jerman J. Abortion incidence and service availability the United States, 2017. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2019.

Chor J, Garcia-Ricketts S, Young D, Hebert LE, Hasselbacher LA, Gilliam ML. Well-woman care barriers and facilitators of low-income women obtaining induced abortion after the affordable care act. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(5):387–92.

Jerman J, Frohwirth L, Kavanaugh ML, Blades N. Barriers to abortion care and their consequences for patients traveling for services: qualitative findings from two states. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2017;49(2):95–102.

Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK, Barar RE, Foster DG. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1687–94.

Rosen JD. The public health risks of crisis pregnancy centers. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(3):201–5.

Foster DG, Gould H, Taylor J, Weitz TA. Attitudes and decision making among women seeking abortions at one U.S. clinic. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44(2):117–24.

Roberts SCM, Foster DG, Gould H, Biggs MA. Changes in alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use over five years after receiving versus being denied a pregnancy termination. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2018;79(2):293–301.

Roberts SCM, Kimport K, Kriz R, Holl J, Mark K, Williams V. Consideration of and reasons for not obtaining abortion among women entering prenatal care in Southern Louisiana and Baltimore Maryland. Sex Res Social Policy. 2019;16(4):476–87.

Kirkman M, Rosenthal D, Mallett S, Rowe H, Hardiman A. Reasons women give for contemplating or undergoing abortion: a qualitative investigation in Victoria Australia. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2010;1(4):149–55.

Delgado-Rodriguez M, Gomez-Olmedo M, Bueno-Cavanillas A, Galvez-Vargas R. Unplanned pregnancy as a major determinant in inadequate use of prenatal care. Prev Med. 1997;26(6):834–8.

Hulsey TM. Association between early prenatal care and mother’s intention of and desire for the pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2001;30(3):275–82.

Goossens J, Van Den Branden Y, Van der Sluys L, Delbaere I, Van Hecke A, Verhaeghe S, et al. The prevalence of unplanned pregnancy ending in birth, associated factors, and health outcomes. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(12):2821–33.

Braveman P, Marchi K, Egerter S, Pearl M, Neuhaus J. Barriers to timely prenatal care among women with insurance: the importance of prepregnancy factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):874–80.

Sable MR, Wilkinson DS. Pregnancy intentions, pregnancy attitudes, and the use of prenatal care in Missouri. Matern Child Health J. 1998;2(3):155–65.

Aztlan EA, Foster DG, Upadhyay U. Subsequent unintended pregnancy among US women who receive or are denied a wanted abortion. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2018;63(1):45–52.

Biggs MA, Brown K, Foster DG. Perceived abortion stigma and psychological well-being over five years after receiving or being denied an abortion. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0226417.

Ralph LJ, Mauldon J, Biggs MA, Foster DG. A prospective cohort study of the effect of receiving versus being denied an abortion on educational attainment. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(6):455–64.

Upadhyay UD, Aztlan-James EA, Rocca CH, Foster DG. Intended pregnancy after receiving vs. being denied a wanted abortion. Contraception. 2019;99(1):42–7.

Foster DG, Biggs MA, Ralph L, Gerdts C, Roberts S, Glymour MM. Socioeconomic outcomes of women who receive and women who are denied wanted abortions in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(3):407–13.

Biggs MA, Upadhyay UD, McCulloch CE, Foster DG. Women’s mental health and well-being 5 years after receiving or being denied an abortion: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(2):169–78.

Roberts SCM, Berglas NF, Kimport K. Complex situations: Economic insecurity, mental health, and substance use among pregnant women who consider - but do not have - abortions. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0226004.

Johnson AA, El-Khorazaty MN, Hatcher BJ, Wingrove BK, Milligan R, Harris C, et al. Determinants of late prenatal care initiation by African American women in Washington. DC Matern Child Health J. 2003;7(2):103–14.

Hulsey TM, Laken M, Miller V, Ager J. The influence of attitudes about unintended pregnancy on use of prenatal and postpartum care. J Perinatol. 2000;20(8 Pt 1):513–9.

Berglas NF, Kimport K, Williams V, Mark K, Roberts SCM. The health and social service needs of pregnant women who consider but do not have abortions. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(5):364–9.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–8.

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–9.

Kost K, Landry DJ, Darroch JE. Predicting maternal behaviors during pregnancy: does intention status matter? Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(2):79–88.

Gerdts C, Dobkin L, Foster DG, Schwarz EB. Side effects, physical health consequences, and mortality associated with abortion and birth after an unwanted pregnancy. Womens Health Issues. 2016;26(1):55–9.

Ralph LJ, Schwarz EB, Grossman D, Foster DG. Self-reported physical health of women who did and did not terminate pregnancy after seeking abortion services. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(4):238–47.

Ralph LJ, Mauldon J, Biggs MA, Foster DG. A prospective cohort study of the effect of receiving versus being denied an abortion on educational attainment. Womens Health Issues. 2019;29(6):455–64.

Upadhyay UD, Biggs MA, Foster DG. The effect of abortion on having and achieving aspirational one-year plans. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:102.

Foster DG, Raifman SE, Gipson JD, Rocca CH, Biggs MA. Effects of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term on women’s existing children. J Pediatr. 2019;205:183-9.e1.

Foster DG, Biggs MA, Raifman S, Gipson J, Kimport K, Rocca CH. Comparison of health, development, maternal bonding, and poverty among children born after denial of abortion vs after pregnancies subsequent to an abortion. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1053–60.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: NS, JW, NW. Data curation: NS, MT. Formal Analysis: NS, MT. Funding acquisition: none. Investigation: NS, JW, MT, SS, RF. Methodology: NS, JW, NW, MT. Project administration: NS, MT. Resources: NS. Software: NS, MT. Supervision: NS, NW. Validation: NS. Visualization: MT, NS. Writing – original draft: MT. Writing – review & editing: MT, NS, NW. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Rochester Medical Center (IRB # STUDY00004185), who granted a waiver of informed consent for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Flow diagram of subject selection.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Toscano, M., Wood, J., Spielman, S. et al. Prenatal care utilization in pregnant women who consider but do not have abortions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 53 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04343-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04343-x