Abstract

Background

Anaemia and related complications during pregnancy is a global problem but more prevalent in sub-Sahara Africa (SSA). Women’s decision-making power has significantly been linked with maternal health service utilization but there is inadequate evidence about adherence to iron supplementation. This study therefore assessed the association between household decision-making power and iron supplementation adherence among pregnant married women in 25 sub-Saharan African countries.

Methods

We used data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) of 25 sub-Saharan African countries conducted between 2010 and 2019. Women's decision-making power was measured by three parameters; own health care, making large household purchases and visits to her family or relatives. The association between women’s decision-making power and iron supplementation adherence was assessed using logistic regressions, adjusting for confounders. The results were presented as adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Approximately 65.4% of pregnant married women had made decisions either alone or with husband in all three decisions making parameters (i.e., own health care, making large household purchases, visits to her family or relatives). The rate of adherence to iron medication during pregnancy was 51.7% (95% CI; 48.5–54.9%). Adherence to iron supplementation was found to be higher among pregnant married women who had decision-making power (AOR = 1.46, 95% CI; 1.16–1.83), secondary education (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI; 1.05–2.00) and antenatal care visit (AOR = 2.77, 95% CI; 2.19–3.51). Wealth quintiles and religion were significantly associated with adherence to iron supplementation.

Conclusions

Adherence to iron supplementation is high among pregnant women in SSA. Decision making power, educational status and antenatal care visit were found to be significantly associated with adherence to these supplements. These findings highlight that there is a need to design interventions that enhance women’s decision-making capacities, and empowering them through education to improve the coverage of antenatal iron supplementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anaemia is a major public health problem [1, 2], and it is estimated that more than two billion people are affected globally [1,2,3]. At least half of all anaemia can be attributed to iron deficiency [4], and the estimated prevalence is higher among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) [5]. Approximately 40% of pregnant women are anaemic worldwide [4]. There are, however, regional variations with the prevalence being higher in Africa (62.3%) and South-East Asia (53.8%) [6, 7].

The risks of anaemia and related complications have been shown to be high among pregnant women [4] because they need additional iron and folic acid to meet their nutritional needs and the growth of the fetus [4]. Anaemia related complications can contribute to miscarriage, intrauterine fetal death, preterm delivery, low birth weight and perinatal mortality [8, 9]. Iron and folic acid deficiency is usually the common cause of anaemia and related complications [4]. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends daily oral iron and folic acid supplementation with 30 mg to 60 mg of elemental iron and 0.4 mg folic acid for pregnant women to prevent maternal anaemia, puerperal sepsis, low birth weight and preterm birth [4, 10].

Although there has been about 50% reduction in anaemia among reproductive-age women [11] as a result of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Goal 2) [12] and the global nutrition targets of World Assembly for 2025 [11], global progress is still slow [13]. There is evidence of poor uptake of iron supplementation among pregnant women, particularly in SSA [14]. In a recent study conducted in 22 SSA countries, Ba and colleagues [14] showed that only 28.7% of pregnant women reported uptake of iron supplementation; even though estimates varied from lowest coverage (1.4%) in Burundi to highest (73%) in Senegal.

Studies in Malawi [15, 16], Ethiopia [17,18,19], and SSA [14] have identified several factors including socioeconomic condition, media exposure, geographic, and timing and number of antenatal care visits as factors linked with adherence to iron supplementation among pregnant women [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Furthermore, there is strong evidence that women’s autonomy is linked with maternal health services, including antenatal care, skilled delivery services and postnatal care [20,21,22,23].

However, to our knowledge, no study has assessed the relationship between women’s decision making and iron supplementation among married pregnant women in SSA countries. This present study, therefore, aimed to investigate the association between household decision-making power and iron adherence among married pregnant women in 25 SSA countries.

Methods

Data source

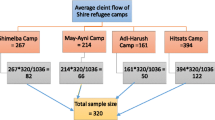

We used data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) of 25 SSA countries conducted between 2010 and 2019. DHS is a nationally representative survey conducted across several low-and middle-income countries with financial and technical assistance from the United States Aid for International Development (USAID) and Inner-City Fund (ICF) International [24, 25]. DHS usually adopt a two-stage stratified sampling technique. In the first stage, clusters, also called enumeration area (EA) were selected using probability proportional to size. In the second stage, a fixed number of households (usually 25 to 30 households) were selected from clusters selected in stage one [26]. The countries were selected if the survey was conducted between 2010 and 2019, and outcome and explanatory variables were available. We included 120,131 married women in the final analysis from the individual recode (IR) file. We included only married women for the analysis because anaemia is common among married women [27]. Furthermore, the variables on decision making were only applicable to married women [28,29,30]. The DHS datasets are freely available for download at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm. We also followed the guidelines for Strengthening of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [31]. Details about selected countries, year of survey and sample are shown in Table 1 below.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was iron supplement adherence. Information about the use of iron supplement was obtained from women who had a live birth within 5 years preceding the survey, by asking whether she took iron tablets or syrup for 90 days and above during pregnancy of last birth. We re-coded responses into a binary variable (0 = No; 1 = Yes) as done in previous studies [14, 15, 32, 33].

Explanatory variables

The key explanatory variable of interest was women’s decision-making power. In the DHS, married women aged 15–49 years were asked three questions about decision making. Questions about who decides on “own (respondent’s) health”, “large household purchases”, and “families or relatives visits” were used to measure women’s decision-making power [28,29,30]. These variables were also used to indirectly assess whether or not a woman was empowered [28,29,30]. The variables were recoded into binary variables. Women who made decisions alone or together with husbands on all three aforementioned decision-making parameters were coded as “1” while those whose responses were not in the affirmative were categorized as otherwise and coded as “0” [28].

Other explanatory variables included women’s age [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], women’s educational status (no formal education, primary school, secondary school, higher), husband’s educational status (no formal education, primary school, secondary school, higher), occupation (not working, professional/technical/managerial, agricultural, manual, others), parity [1,2,3, 5], 5+), place of residence (urban, rural), religion (Christian, Muslim, others) and number of antenatal care (ANC) visit (< 4 visits, 4+ visits). We also included wealth index (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest). In the survey, wealth index was computed using durable goods, household characteristics and basic services [34]. Other variables included exposure to media (newspaper, radio or television (TV)) which was assessed in terms of frequency (no exposure “no” or less than once a week “yes”).

Statistical analysis

First, descriptive statistics were performed to obtain the prevalence of iron adherence and it distribution across the outcome, explanatory variables. Second, we conducted bivariate logistic regression analysis with each of the explanatory variables and the outcome variable (iron adherence) to select candidate explanatory variables for the multivariable logistic regression model, only variables that were statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) in the bivariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariable logistic regression. Third, a multicollinearity test was conducted using variance inflation factor (VIF) to check for collinearity among selected variables. The test showed no evidence of collinearity among the variables (Mean VIF = 2.06, Max VIF = 4.81, Min VIF = 1.07). Finally, we performed a multivariable logistic regression (MLR) to assess the association between the selected explanatory variables and outcome variable. The goodness-of-fit of the regression model was assessed using Hosmer-Lemeshow [35], and we observed better fitting model (P = 0.3071). The results were presented using adjusted odd ratio (AOR) at 95% confidence interval (CI). The analysis was carried out using Stata version-14 software (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). We used the “svyset” command in Stata to account for the complex survey design including weight, cluster and strata.

Ethical considerations

We used publicly available secondary data for analysis of this study (available at: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm). Ethical procedures were conducted by institutions that funded, commissioned, and managed the surveys. Thus no further ethical clearance was required. All data were anonymized prior to the authors receiving the data. For further details related to ethical issues, see http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 119,279 pregnant married women were included in this study and their socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of them, about 7.9% were 15–19 years old. More than a quarter (27.5%) and one-fifth (21.1%) of the respondents and their husbands had no formal education respectively. About one in four (25.3%) of the respondents had no job and 35.3% were living in rural areas.

Distribution of iron supplementation adherence across explanatory variables

The prevalence of iron supplementation adherence by explanatory variables is shown in Table 2. We observed that the prevalence of iron supplementation adherence varied across socio-demographic sub-groups; for example, adherence to iron supplementation was found to be higher among respondents with higher education (65.4%) compared to those with no education (39.6%). Iron supplementation adherence varied approximately from 23.6 to 52.6% among Muslim and Christian married women respectively. Higher prevalence of iron supplementation was also observed among married women with 4 and above ANC visit (59.2%) compared to those with less than 4 ANC visits (29.9%).

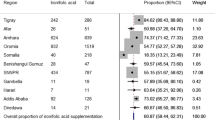

Prevalence of iron supplementation adherence across countries

The prevalence of iron supplementation adherence across 25 SSA countries is shown in Fig. 1. We observed the lowest prevalence of iron adherence in Burundi (3.8%), Rwanda (5.5%), Congo Democratic Republic (11%), Ethiopia (14.9%) and Kenya (16.8%). The highest prevalence of iron adherence was observed in Zambia (83.8%) followed by Senegal (76.7%), Gabon (70.3%), Benin (70.3%), Ghana (68.5%) and Cameroon (67%).

Association between women’s decision-making power and iron supplementation adherence

Bivariate logistic regression results

Table 3 shows results of the bivariate and multivariable logistic regressions. The bivariate analysis showed that women’s decision-making power was significantly associated with adherence to iron supplementation. We also found women’s age, women’s educational status, husband’s educational status, women’s occupation, wealth index, media exposure, parity, place of residence, religion and number of ANC visit to be significantly associated with adherence to iron supplementation among married women in SSA.

Multivariable logistic regression results

As shown in Table 3, we found a significant association between women’s decision making power and adherence to iron supplementation, where the odds of adherence was seen to be higher among married women who had decision-making power on all the decision making parameters (AOR = 1.46, 95% CI; 1.16–1.83) compared to married women who had no decision-making power. Furthermore, we observed a higher probability of iron supplementation adherence for married women who had secondary education (AOR = 1.45, 95% CI; 1.05–2.00) compared to married women who had no formal education. Higher odds of iron adherence was also observed among married women who had four or more ANC visit (AOR = 2.77, 95% CI; 2.19–3.51) compared to those who had less than four ANC visits. The likelihood of adherence to iron supplementation was found to lower among poorer households (AOR = 0.68, 95% CI; 0.46–0.99) and Muslim women (AOR = 0.20, 95% CI; 0.05–0.76).

Regarding country specific findings, married women who had decision making power were more likely to have adherence to iron supplementation in Angola (AOR = 1.36, 95% CI; 1.19–1.55), Cameroon (AOR = 1.39, 95% CI; 1.19–1.63), Gambia (AOR = 1.30, 95% CI; 1.15–1.47), Liberia (AOR = 1.79, 95% CI; 1.23–2.62), Malawi (AOR = 1.13, 95% CI; 1.04–1.23), Senegal (AOR = 1.54, 95% CI; 1.28–1.84), Uganda (AOR = 1.49, 95% CI; 1.34–1.66) and Zambia (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI; 1.04–1.42). Surprisingly, the inverse was found in Mali (AOR = 0.70, 95% CI; 0.57–0.86) and Togo (AOR = 0.74, 95% CI; 0.63–0.87) (Table 4).

Discussion

Using nationally representative data, we assessed the association between household decision- making power and adherence to iron supplementation among married women in 25 SSA countries. Overall, the results revealed that about 51.7% of married pregnant women in the selected countries reported intake of iron tablets/syrups for 90 days or more. This estimate is lower than what was found in previous SSA countries, where about 28.7% of women adhered to an intake of iron supplements [14]. These inconsistent findings may be attributed to the study population [14]. In this current study, only married pregnant woman were included in the analysis as opposed to unmarried women in prior studies [14]. We, however, observed variations in the prevalence of iron supplement adherence across SSA countries, with the lowest prevalence in Burundi (3.8%) and the highest prevalence in Zambia (83.8%).

We found women’s decision-making power to be positively associated with adherence to iron supplementation among pregnant married women. Although no known study assessed the relationship between women’s decision-making power and iron adherence in SSA, there is some evidence that women’s decision-making power is a contributing factor for better utilization of maternal health in some countries including Nepal [20], Bangladesh [36], India [21], Cameroon [23], Ethiopia [37] and Benin [38]. Spousal communication has been shown to be vital for women’s decision-making power [36], where prior studies suggest that poor communication and non-support from partners may lead to poor uptake of maternal health services [36, 39]. Other possible explanations include socioeconomic status [40, 41] and cultural norm [42]. In a recent study conducted in Senegal Sougou et al. showed that women with higher socioeconomic status had better decision-making capacities [43].

Consistent with prior studies in Malawi [15], Ethiopia [17, 18] and SSA [14] we found that women who had formal education were more likely to use iron supplements than non-educated women. This is because educated women may be well informed about their health [14, 15, 44], have access to nutritional information [45] and may know the benefits of iron supplementation [46] Furthermore, they may be knowledgeable about maternal health services, which can enable them seek healthcare services [47, 48].

We found religion to be significantly associated with to adherence to iron supplementation. The likelihood of iron supplement intake was lower among Muslim than Christians. Although there is no prior evidence of the relationship between iron supplement intake and religion, a study conducted in Nigeria showed no significant difference in the uptake of maternal health services between Muslim and Christian women [49]. However, studies in Ghana [50], Nigeria [51, 52] and Benin [53] suggest a significant association between religion and maternal healthcare access and service utilization.

Finally, a significant association was found between the number of ANC visits and iron supplement adherence. Women who had four or more visits were more likely to use iron supplements than those who had less than four ANC visits, consistent with prior studies [14, 16, 19, 54]. Pregnant women generally receive iron supplementation through ANC visits at health facilities [10]; thus, this finding is expected as health facilities may find ANC visits as a good opportunity for the distribution of iron supplements for pregnant women [10, 11].

Strength and limitation of the study

The major strengths of our study include the large nationally representative sample and a multi-country analysis. Nonetheless, some limitations were also observed. First, a causal-effect relationship cannot be established because of the cross-sectional nature of the study. Second, the DHS relied on self-reported data which may be prone to recall bias. Lastly, due to data availability and constrains, we used surveys that were conducted at different time points in the selected countries.

Conclusion

This study shows that approximately 65.4% of married pregnant women had decision-making power, and about half (51.7%) used iron supplements during pregnancy. Pregnant women with decision making power were more likely to use iron supplements. Socio-demographic factors including women’s educational level, household economic status, religion and number of ANC visits were significantly associated with adherence to iron supplementation. These findings highlight that there is a need to design interventions that enhance women’s decision-making capacities, and empowering them through education to improve the coverage of antenatal iron supplementation.

Availability of data and materials

Data for this study were sourced from Demographic and Health surveys (DHS) and available here: http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

References

Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, Wulf SK, Johns N, Lozano R, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123(5):615–24.

Global Burden of Disease DALYs, Hale Collaborators, Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Abbasoglu Ozgoren A. Global, regional, and national disability adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990-2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145–91.

Harding KL, Aguayo VM, Namirembe G, Webb P. Determinants of anemia among women and children in Nepal and Pakistan: an analysis of recent national survey data. Matern Child Nutr. 2018;(Suppl 4):e12478. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12478.

WHO: Daily iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy. https://www.who.int/elena/titles/guidance_summaries/daily_iron_pregnancy/en/. Accessed on 2 April, 2021.

World Health Organization. The global prevalence of anemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from at: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/micronutrients/global_prevalence_anaemia_2011/en/. [Accessed on 05 April 2021]

WHO. The global prevalence of anaemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/177094/1/9789241564960_eng.pdf. Accessed on 05 April 2021

Benoist BD, McLean E, Egll I, Cogswell M. Worldwide prevalence of anaemia 1993–2005. WHO global database on anaemia; 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/43894/1/9789241596657_eng.pdf. Accessed on 05 April 2021.

Georgieff MK. Iron deficiency in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;14 March:S0002–9378(20)30328–30328 doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.03.006.

Juul SE, Derman RJ, Auerbach M. Perinatal iron deficiency: implications for mothers and infants. Neonatology. 2019;115(3):269–74. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495978.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. Geneva: world health Organization; 2016.

Global anaemia reduction efforts among women of reproductive age: impact, achievement of targets and the way forward for optimizing efforts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO.

WHO. Intervention by global target. Available at: https://www.who.int/elena/global-targets/en/. Accessed on 27 April 2021.

Chaparro CM, Suchdev PS. Anemia epidemiology, pathophysiology, and etiology in low- and middle-income countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2019;1450(1):15–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14092.

Ba DM, Sentongo P, Kjerulff KH, Na M, Liu G, Gao X, et al. Adherence to Iron Supplementation in 22 Sub-Saharan African Countries and associated factors among pregnant women: a large population-based study. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3:nzz120.

Titilayo A, Palamuleni ME, Omisakin O. Socio-demographic factors influencing adherence to antenatal iron supplementation recommendations among pregnant women in Malawi: analysis of data from the 2010 Malawi demographic and health survey. Malawi MedJ. 2016;28(1):1–5.

Wenjuan W, Benedict RK, Mallick L. The role of health facilities in supporting adherence to Iron-folic acid supplementation during pregnancy: a case study using DHS and SPA data in Haiti and Malawi. DHS working paper, vol. No. 160. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF; 2019.

Nasir BB, Fentie AM, Adisu MK. Adherence to iron and folic acid supplementation and prevalence of anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2020; 15(5): e0232625.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232625.

Taye B, Abeje G, Mekonen A. Factors associated with compliance of prenatal iron folate supplementation among women in Mecha district, Western Amhara: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:43. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2015.20.43.4894.

Getachew M, Abay M, Zelalem H, Gebremedhin T, Grum T, Bayray A. Magnitude and factors associated with adherence to Iron-folic acid supplementation among pregnant women in Eritrean refugee camps, northern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):83 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884–018–1716-2.

Adhikari R. Effect of Women’s autonomy on maternal health service utilization in Nepal: a cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-0160305-7.

Mistry R, Galal O, Lu M. Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: a contextual analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(6):926–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.008.

Wado YD. Women’s autonomy and reproductive healthcare-seeking behavior in Ethiopia. Women Health. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1353573.

Yaya S, Zegeye B, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-Z, Ameyaw EK, Adjei NK, et al. Predictors of skilled birth attendance among married women in Cameroon: further analysis of 2018 Cameroon demographic and health survey. Reprod Health 2021; 18:70 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01124-9.

The DHS Program- quality information to plan, monitor and improve population, health, and nutrition programs. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/. Accessed on April 2, 2021.

DHS Program. Methodology: survey type. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey-Types/dHs.cfm. Accessed on April 5, 2021.

DHS Program. Guide to DHS statistics. Analyzing DHS data. Available at: https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/Analyzing_DHS_Data.htm. Accessed on 30 March 2021.

Teshale AB,Tesema GA, Worku MG, Yeshaw Y, Tessema ZT. Anemia and its associated factors among women of reproductive age in eastern Africa: a multilevel mixed-effects generalized linear model. PLoS One 2020;15(9): e0238957.https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238957.

Hanmer L, Klugman J. "Exploring women's agency and empowerment in developing countries: Where do we stand?." Feminist Economics 22, no. 1: 237–263.

Kishor S, Subaiya L. Understanding Women’s empowerment: a comparative analysis of demographic and health surveys (DHS) data. DHS comparative reports no. 20. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Macro International Inc.; 2008. https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-cr20-comparativereports.cfm

Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK, et al. Guide to DHS statistics. Rockville, Maryland, USA: ICF; 2018.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–9.

Gebremedhin S, Samuel A, Mamo G, Moges T, Assefa T. Coverage, compliance and factors associated with utilization of iron supplementation during pregnancy in eight rural districts of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):607.

Haile MT, Jeba AB, Hussen MA. Compliance to prenatal iron and folic acid supplement and associated factors among women during pregnancy in south East Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Nutr Health Food Eng. 2017;7(2):272–7. https://doi.org/10.15406/jnhfe.2017.07.00235.

Rutstein SO, Johnson K. The DHS wealth index. DHS comparative reports no. 6. ORC Macro: Calverton, Maryland; 2004.

IBM. Tests of Model Fit: IBM Documentation. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/SaaS?topic=diagnostics%2D%2Dtests-model-fit. Accessed on 25 Apr 2021.

Ghose B, Feng D, Tang S, Yaya S, He Z, Udenigwe O, et al. Women’s decision-making autonomy and utilisation of maternal healthcare services: results from the Bangladesh demographic and health survey. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017142 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017142.

Tekelab T, Yadecha B, Melka AS. Antenatal care and women’s decision making power as determinants of institutional delivery in rural area of Western Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:769 https:// doi. org/10.1186/s13104–015-1708-5.

Yaya S, Uthman OA, Amouzou A, Ekholuenetale M, Bishwajit G. Inequali- ties in maternal health care utilization in Benin: a population based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:194 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884–018-1846-6.

Mullany BC, Becker S, Hindin MJ. The impact of including husbands in antenatal health education services on maternal health practices in urban Nepal: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007;22:166–76.

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, et al. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11190.

Obeidat RF. How can women in developing countries make autonomous health care decisions? Womens Health Int. 2016;2:116.

Mungiria NL. Social-cultural factors affecting women in decision making and conflict resolutions activities in Garissa County. Thesis Paper, University of Nairobi, 2013.

Sougou NM, Bassoum O, Faye A, Leye MMM. Women’s autonomy in health decision-making and its effect on access to family planning services in Senegal in 2017: a propensity score analysis. BMC Public Health 2020; 20:872 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09003-x.

Agegnehu G, Atenafu A, Dagne H, Dagnew B. Adherence to iron and folic acid supplement and its associated factors among antenatal care attendant mothers in Lay Armachiho health centers, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2017. Int J Reprod Med. 2019;2019:5863737.

Weerasekara PC, Withanachchi CR, Ginigaddara GAS, Ploeger A. Food and nutrition-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices among reproductive-age women in marginalized areas in Sri Lanka. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3985. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113985.

Kamau MW, Mirie W, Kimani ST. Maternal knowledge on iron and folic acid supplementation and associated factors among pregnant women in a rural county in Kenya. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2019;10:74–80.

Shahabuddin A, Delvaux T, Abouchadi S, Sarker M, De Brouwere V. Utilization of maternal health services among adolescent women in Bangladesh: a scoping review of the literature. Tropical Med Int Health. 2015;20(7):822–9.

Tiruneh FN, Chuang K-Y, Chuang Y-C. Women’s autonomy and maternal healthcare service utilization in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:718. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2670-9.

Al-Mujtaba M, Cornelius LJ, Galadanci H, Erekaha S, Okundaye JN, Olusegun A. Adeyemi OA, et al. Evaluating religious influences on the utilization of maternal health services among Muslim and Christian women in north-Central Nigeria. Biomed Res Int 2016, 3645415, pp8.

Ganle JK. “Why Muslim women in northern Ghana do not use skilled maternal healthcare services at health facilities: a qualitative study,“BMC Int Health Hum Rights, 2015; 15,1, 10.tp://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/3645415

Doctor HV, Findley SE, Ager A, Commeto G, Afenyadu GY, Adamu F, et al. Using community based research to shape the design and delivery of maternal health services in northern Nigeria. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(39):104–12.

Fagbamigbe AF, Idemudia ES. Barriers to antenatal care use in Nigeria: evidences from non-users and implications for maternal health programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):95.

Zegeye B, El-khatib Z, Ameyaw EK, Seidu A, Ahinkorah BO, Keetile M, et al. Breaking barriers to healthcare access: a multilevel analysis of individual- and community-level factors affecting Women’s access to healthcare Services in Benin. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):750.

Sununtnasuk C, D’Agostino A, Fiedler JL. “Iron+folic acid distribution and consumption through antenatal care: identifying barriers across countries.” Public Health Nutr 2016; 19(4):732–742. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001652.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MEASURE DHS project for their support and for free access to the original data.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY and BZ contributed to the study design and conceptualization, reviewed the literature and performed the analysis. NKA, CZO, BOA, EKA and AS provided technical support and critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. SY had final responsibility to submit for publication. All authors read and amended drafts of the paper and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethics approval was not required for this study since the data is secondary and is available in the public domain. More details regarding DHS data and ethical standards are available at: http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Consent for publication

No consent to publish was needed for this study as we did not use any details, images or videos related to individual participants. In addition, data used are available in the public domain.

Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zegeye, B., Adjei, N.K., Olorunsaiye, C.Z. et al. Pregnant women’s decision-making capacity and adherence to iron supplementation in sub-Saharan Africa: a multi-country analysis of 25 countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 822 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04258-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04258-7