Abstract

Background

Conjoined twins are a rare and serious complication of monochorionic twins. The total incidence is 1.5 per 100,000 births, and about 50% are liveborn. Prenatal screening and diagnosis of conjoined twins is usually performed by ultrasonography. Magnetic resonance imaging can be used to assist in the diagnosis if necessary. Conjoined twins in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancy are extremely rare.

Case presentation

We reported three cases of dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancy with conjoined twins. Due to the poor prognosis of conjoined twins evaluated by multidisciplinary teams, selective termination of conjoined twins was performed in three cases. In case 1, selective reduction of the conjoined twins was performed at 16 gestational weeks, and a healthy female baby weighing 3270 g was delivered at 37 weeks. In case 2, the conjoined twins were selectively terminated at 17 weeks of gestation, and a healthy female baby weighing 2760 g was delivered at 37 weeks and 4 days. In case 3, the conjoined twins were selectively terminated at 15 weeks and 2 days, and a healthy female baby weighing 2450 g was delivered at 33 weeks and 6 days. The babies of all three cases were followed up and are in good health.

Conclusion(s)

Surgical separation is the only treatment for conjoined twins after birth. Early determination of chorionicity and antenatal diagnosis of conjoined twins in triplet gestations are critical for individualized management options and the prognosis of normal triplets. Expecting parents should be extensively counseled by multidisciplinary teams. If there are limitations in successful separation after birth, early selective termination of the conjoined twins by intrathoracic injection of potassium chloride may be a procedure in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancy to improve perinatal outcomes of the normal triplet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Conjoined twins are a rare and serious complication of monochorionic twins. The total incidence is 1.5 per 100,000 births, and about 50% are liveborn [1]. The survival rate of conjoined twins is low, and the prognosis is generally poor. Common triplet pregnancies are monochorionic triamniotic, trichorionic triamniotic, and dichorionic triamniotic, and only 2% are dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancies [2]. Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy are rare, and the incidence is less than one in a million deliveries [3]. Conjoined twins in a dichorionic diamniotic (DCDA) triplet pregnancy are extremely rare. So far, there are only a few published articles relevant to conjoined twins in triplet pregnancies, and the majority of them are case reports. We have only found 10 cases of conjoined twins reported in DCDA triplet pregnancies.

Here, we reported three cases of conjoined twins in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancies, in which selective fetal reduction by intracardiac injection of potassium chloride was performed. As a result, another fetus continued to grow and develop in the uterus and was delivered at full term, which was a good pregnancy outcome. Additionally, we used a list of keywords including “conjoined twins”, “triplets,” “triplet pregnancy”, and “multiple pregnancy” to perform an extensive Medline search and conducted a literature review in English and Chinese about conjoined twins in triplet pregnancies. Written informed consent was obtained from the couples before the procedure and manuscript publication. The treatment procedure followed ethical principles, and all data was collected from chart reviews. This study was approved by the ethical committees at the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 44-year-old woman, gravida 4, para 1, spontaneously conceived. Ultrasound examination at 12 weeks of gestation showed cranio-thoraco-omphalopagus conjoined twins in a DCDA triplet pregnancy. In the conjoined twins, there was only one skull halo, two sets of thalamus and cerebellum, and partial fusion of frontal brain tissue of two fetuses. Partial fusion of the neck, which segregated cystic space, was seen in both fetal necks, as well as a cystic mass measuring 2.9 × 1.9 cm and 2.8 × 1.8 cm, chest fusion, two hearts with a fetal heartbeat, abdominal fusion, two bladders, two spines with abnormal physiological curvature, four upper limbs, and four lower limbs (Fig. 1A). The couple had no family history of congenital anomalies.

The staffs of multidisciplinary team extensively counseled the couple regarding the treatment and prognosis of the conjoined twins. The parents chose selective termination of the conjoined twins. Thus, intrathoracic injection of potassium chloride (KCl) to the conjoined twins was performed under an ultrasound-guided procedure at 16 weeks of gestation. Images of the live fetus and conjoined twins after selective termination are shown in Fig. 1B. The couple refused chromosome examination in conjoined twins, and amniocentesis was performed on the other fetus. The result of chromosome microarray analysis in the other fetus was normal.

The woman was followed up closely. Cesarean section was performed due to central placenta previa at 37 weeks. The healthy female baby weighed 3270 g with Apgar scores of 9 and 10 at the first and fifth minute, respectively, whereas the papyraceous conjoined fetuses weighed 51 g (Fig. 1C). The baby is now 1 year and 5 months old, and she is in good health.

Case 2

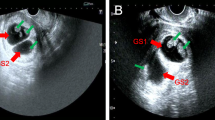

A 22-year-old woman, gravida 1, para 0, underwent in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. At 13 weeks and 5 days of gestation, ultrasound examination showed a DCDA triplet pregnancy with thoraco-omphalopagus conjoined twins. The chest and abdominal wall of the conjoined twins were connected, and only one heart echo was found. The livers of the two fetuses were connected, and the limbs were independent. Independent gastric vesicles and the spinal echoes of each fetus could be found (Fig. 2A). The couple had no family history of congenital anomalies.

After extensive counsel by the multidisciplinary team, selective termination of the conjoined twins was chosen by the couple. Thus, ultrasound-guided intrathoracic injection of KCl at 17 weeks of gestation was performed on the conjoined twins. Images of the live fetus and conjoined twins after selective termination are shown in Fig. 2B. The couple was only willing to perform amniocentesis in the other fetus, not the conjoined twins. The result of chromosome microarray analysis in the other fetus was normal.

At 37 weeks and 4 days, a healthy female baby weighing 2760 g was delivered with Apgar scores of 10 and 10 at 1 and 5 min, respectively, whereas the papyraceous conjoined fetuses weighed 79 g (Fig. 2C). The baby is now 1 year and 4 months old, and she is in good health.

Case 3

A 29-year-old woman, gravida 3, para 1, conceived spontaneously. Due to the suspicion of omphalopagus conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy, she was transferred to our department at 14 weeks, and ultrasound examination in our hospital showed omphalopagus conjoined twins in a DCDA triplet pregnancy. In the conjoined twins, there was a 4.7 × 3.5 × 4.5 cm cystic space in the amniotic cavity of the conjoined twins, which was connected to the two bladders of conjoined twins. Only one allantoic artery could be seen on the surface of both fetal bladders, and a urachal cyst was suspected to be present (Fig. 3A). The couple had no family history of congenital anomalies.

The staffs of multidisciplinary team extensively counseled the couple. Based on the couple’s choice, selective termination of the conjoined twins was performed by ultrasound-guided intrathoracic injection of KCl at 15 weeks and 2 days of gestation, and amniocentesis was done in the other fetus, not in the conjoined twins. Images of the live fetus and conjoined twins after selective termination are shown in Fig. 3B. The result of chromosome microarray analysis in the living fetus was normal.

At 33 weeks and 6 days, a healthy female baby weighing 2450 g was delivered due to suspected fetal distress, with Apgar scores of 8 and 10 at 1 and 5 min, respectively, whereas the papyraceous conjoined fetuses weighed 84 g. The baby is now one month old, and she is in good health.

Discussion and conclusions

Conjoined twins are a rare and serious complication of monochorionic twins. The total incidence is 1.5 per 100,000 births, and about 50% are liveborn [1]. Conjoined twins are more common in females, and the male-to-female ratio is 1:3 [4]. The pathogenesis of conjoined twins is unclear. Fission theory [5] and fusion theory [6] are widely accepted. The fission theory suggests that the embryo undergoes incomplete division 13–15 days after fertilization, resulting in conjoined twins. The fusion theory suggests that two separate embryos undergo a second fusion 13 days after fertilization.

Conjoined twins can be classified according to their most prominent conjoined parts. There are many classifications of conjoined twins. Broadly speaking, it can be divided into dorsally conjoined twins and nondorsally conjoined twins [6]. According to Spencer’s classification [7], there are eight types of conjoined twins as follows: (1) cephalogapus, (2) thoracopagus, (3) omphalopagus, (4) ischiopagus, (5) parapagus, (6) craniopagus, (7) pygopagus, and (8) rachipagus. However, many conjunction types show overlapping conjunction patterns, leading to the various phenotypes of conjoined twins. Thoracoomphalopagus is one of the most common types of conjoined twins with a rate of 75% [3].

Prenatal screening and diagnosis of conjoined twins is usually performed by ultrasonography [4]. Characteristics of prenatal ultrasound diagnosis of conjoined twins include [4, 8]: (1) a single placenta without amniotic septum, (2) fetuses lying in the same constant position with heads and body parts at the same level persistently, (3) inseparable body and skin contours, (4) fetuses facing each other with hyperflexion of cervical spines, sharing of organs, and a single umbilical cord with more than three vessels, (5) fewer limbs of some conjoined twins than that of normal twins, and (6) abnormal flexion of the spine. MRI can be used to assist in the diagnosis if necessary [9].

Conjoined twins have a low survival rate, and the prognosis is generally poor. Twenty-five percent of live births live to the age of surgery [5]. Only 60% of surgical separation cases survive [10]; therefore, early antenatal diagnosis is important. The prognosis is mainly affected by specific fusion parts and related malformations. Due to the high incidence of complex heart defects, the survival rate of thoracopagus is the lowest [11]. Elective separation is feasible in omphalopagus, pygopagus, and some craniopagus and thoracopagus twins. Separation is not possible in cephalopagus, parapagus, and rachipagus twins [1]. The difficulty and prognosis of surgical treatment are related to the location and degree of conjoined parts. The separation of conjoined twins is complex and expensive, involving multidisciplinary teams. When separation involves the unequal sharing of limbs and organs, or when separation leads to the death of one of the conjoined twins, complex ethical issues will also arise [1].

In clinical management, excluding the severity of the case, parents’ social situation, religious, and psychological beliefs should be considered.

In triplet pregnancies, one should be aware about the possibility of conjoined twins. Triplet pregnancies contribute significantly to maternal complications, including spontaneous abortion, preterm birth, gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, antepartum bleeding, anemia, hyperemesis gravidarum, cesarean section, and postpartum hemorrhage. In addition, women delivering triplets have a significantly higher risk of cardiac disease and acute or chronic lung disease compared to women who give birth to twins [12, 13]. Compared with singletons and twins, triplets have a higher risk of adverse perinatal outcomes due to higher rates of preterm birth, low birth weight, and congenital anomalies [14, 15]. Therefore, neonatal morbidity and mortality rates may also increase. The risk of spontaneous loss of the pregnancy prior to 24 weeks is 15–18% for triplets and 8% for twins [16, 17] and preterm delivery prior to 34 weeks is 50%, while approximately 8–17% of triplets are delivered between 24 and 28 weeks [18, 19]. In triplets, the rate of cerebral palsy is 28 per 1000 live births, compared to 1.6 per 1000 live births in singletons and 7 per 1000 live births in twin pregnancies. The infant mortality rate in triplets is 52.5 per 1000 live births, compared to 5.4 per 1000 live births in singletons and 23.6 per 1000 live births in twins [20].

Conjoined twins in triplet pregnancy are considered a unique phenomenon that is accompanied by a wide variety of congenital abnormalities and has hazardous consequences for both fetuses and parents, which also occurs in monochorionic diamniotic (MCDA) triplets and DCDA triplets. Due to its rarity, triplet pregnancies with increased maternal complications, perinatal morbidity and mortality, provide a great challenge for staff to undertake the complete workup, determine shared anatomy, evaluate maternal-fetal prognosis, and decide management (to continue as a triplet gestation, termination of pregnancy, or selective termination of conjoined twins) once a diagnosis is reached. Up to now, no consensus has been achieved.

We used a list of keywords including “conjoined twins,” “triplet pregnancy,” “dichorionic diamniotic,” “monochorionic”, and “multiple pregnancy” to perform an extensive Medline and CNKI search of the literature in English and Chinese about the perinatal management and outcomes of conjoined twins in triplet pregnancies. To the best of our knowledge, the number of published papers related to conjoined twins in triplet pregnancies was less than 30. There were four reported cases of unclear chorionic triplet pregnancies [21,22,23,24]. Conjoined twins all had a poor prognosis. Detailed information is shown in Table 1. We found 14 cases of monochorionic triplet pregnancies with conjoined twins [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Detailed information is shown in Table 2. Due to placental vascular anastomoses between the conjoined twins and the other fetus, the prognosis of the normal triplet was poor after selective fetal reduction. We also found 10 cases of conjoined twins in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancies [3, 31, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Detailed information is shown in Table 3. Compared with conjoined twins in monochorionic triplet pregnancies, the prognosis in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancies is generally better. Except for two cases, all cases achieved good pregnancy outcomes after selective reduction.

Over other studies, the advantage of our study is that we reported three cases of conjoined twins in DCDA triplet pregnancy, and detailed information about maternal, fetal, and neonatal status is provided in our study. Due to the poor prognosis of conjoined twins evaluated by multidisciplinary teams, conjoined twins were selectively terminated by transabdominal intracardiac potassium chloride injection in the second trimester. Among our three cases, the pregnant women were stable throughout the pregnancy, two cases with term delivery (case 1 and case 2), one case with preterm delivery at 33 weeks and 6 days of gestation due to suspected fetal distress. All the cases have a good prognosis, and the three babies were followed up and are currently in good health.

This study reviewed the published papers about perinatal outcomes on conjoined twins in DC and MC triplet pregnancies and gives three new cases in the selective termination of the conjoined twins and the outcome of normal triplets in DCDA triplets, which may be useful for making clinical decisions in triplet pregnancies with conjoined twins. The limitation of this study is the loss of some data in the literature review due to the lack of information in the published papers.

In conclusion, due to the rarity of triplet pregnancies with conjoined twins, experience with the treatment is limited. Obstetricians and ultrasound specialists must be aware of the rare complications and focus on early ultrasound diagnosis. Early antenatal diagnosis of conjoined twins and determination of chorionicity of triplet gestations are critical for individualized management options and the prognosis of the normal fetus. Expecting parents should be extensively counseled by a multidisciplinary team. Early selective termination of the conjoined twins by intrathoracic injection of potassium chloride may be a procedure in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancies to improve the perinatal outcomes of the normal fetus in triplets.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DCDA:

-

Dichorionic diamniotic

- MCDA:

-

Monochorionic diamniotic

- KCl:

-

Potassium chloride

References

Frawley G. Conjoined twins in 2020 – state of the art and future directions. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020;33(3):381–7.

Fennessy KM, Doyle LW, Naud K, et al. Triplet pregnancy: is the mode of conception related to perinatal outcomes? Twin Res Hum Genet. 2015;18(3):321–7.

Ozcan HC, Ugur MG, Mustafa A, et al. Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy. A rare obstetrical dilemma. Saudi Med J. 2017;38(3):307–9.

Mian A, Gabra NI, Sharma T, et al. Conjoined twins: from conception to separation, a review. Clin Anat. 2017;30(3):385–96.

Kaufman MH. The embryology of conjoined twin. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20(8–9):508–25.

Boer LL, Schepens-Franke AN, Oostra RJ. Two is a crowd: two is a crowd: on the enigmatic etiopathogenesis of conjoined twinning. Clin Anat. 2019;32(5):722–41.

Spencer R. Anatomic description of conjoined twins: a plea for standardized terminology. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(7):941–4.

Mathew RP, Francis S, Basti RS, et al. Conjoined twins–role of imaging and recent advances. J Ultrason. 2017;17(71):259–66.

Wataganara T, Ruangvutilert P, Sunsaneevithayakul P, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound for prenatal assessment of conjoined twins: additional advantages? J Perinat Med. 2017;45(6):667–91.

Brizot Mde L, Liao AW, Lopes LM, et al. Conjoined twins: prenatal diagnosis,delivery and postnatal outcome. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2011;33(5):211–8.

Sage E, Thomas A, Sundgren N. Conjoined Twins: Pre-Birth Management,Changes to NRP, and Transport. Semin Perinatol. 2018;42(6):321–8.

Wen SW, Demissie K, Yang Q, Walker MC. Maternal morbidity and obstetric complications in triplet pregnancies and quadruplet and higher-order multiple pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(1):254–8.

Luke B, Brown MB. Maternal morbidity and infant death in twin vs triplet and quadruplet pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):401 e401–410.

Luke B, Brown MB. The changing risk of infant mortality by gestation, plurality, and race: 1989-1991 versus 1999-2001. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2488–97.

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Kirmeyer S, Mathews TJ, et al. Births: final data for 2009. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2011;60:1–70.

Evans MI, Britt DW. Multifetal pregnancy reduction: evolution of the ethical arguments. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(4):295–302.

Anthoulakis C, Dagklis T, Mamopoulos A, Athanasiadis A. Risks of miscarriage or preterm delivery in trichorionic and dichorionic triplet pregnancies with embryo reduction versus expectant management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(6):1351–9.

Dickey RP, Taylor SN, Lu PY, et al. Spontaneous reduction of multiple pregnancy: incidence and effect on outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(1):77–83.

Zipori Y, Haas J, Berger H, Barzilay E. Multifetal pregnancy reduction of triplets to twins compared with non-reduced triplets: a meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2017;35(3):296–304.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Multifetal Gestations: Twin, Triplet, and higher-order multifetal pregnancies: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 231. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(6):1140–3.

Hartung RW, Yiu-Chiu V, Aschenbrener CA. Sonographic diagnosis of Cephalothoracopagus in a triplet pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1984;3(3):139–41.

Koontz WL, Layman L, Adams A, et al. Antenatal sonographic diagnosis of conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153(2):230–1.

Apuzzio JJ, Ganesh VV, Chervenak J, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of dicephalous conjoined twins triplet pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159(5):1214–5.

Kaveh M, Kamrani K, Naseri M, et al. Dicephalic Parapagus Tribrachius conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy: a case report. J Family Peprod Health. 2014;8(2):83–6.

Tan KL, Tock EP, Dawood MY, et al. Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy. Am J Dis Child. 1971;122(5):455–8.

Lipitz S, Ravia J, Zolti M, et al. Sequential genetic events leading to conjoined twins in a monozygotic triplet pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(12):3130–2.

Chang DY, Chang RY, Chen RJ, et al. Triplet pregnancy complicated by intrauterine fetal death of conjoined twins from an umbilical cord accident of an Acardius. A Case Report. J Reprod Med. 1996;41(6):459–62.

Gardeil F, Greene R, NiScanaill S, et al. Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(4):Pt 2:716.

Wax JR, Royer D, Steinfeld JD, et al. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of thoracopagus conjoined twins in a monoamniotic triplet gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181(3):755–6.

Zeng SM, Yankowitz J, Murray JC. Conjoined twins in a monozygotic triplet pregnancy: prenatal diagnosis and X-inactivation. Teratology. 2002;66(6):278–81.

Sepulveda W, Munoz H, Alcalde JL. Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy:early prenatal diagnosis with three-dimensional ultrasound and review of the literature. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22(2):199–204.

Suzumori N, Kaneko S, Nakanishi T, et al. First trimester diagnosis of conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126(1):132–3.

Sellami A, Chakroun N, Frikha R, et al. Xipho-omphalopagus conjoined twins in a spontaneous triplet pregnancy:autopsy findings. APSP J Case Rep. 2013;4(3):49.

Talebian M, Rahimi-Sharbaf F, Shirazi M, et al. Conjoined twins in a monochorionic triplet pregnancy after in vitro fertilization:a case report. Iran J Reprod Med. 2015;13(11):729–32.

Yuan H, Zhou Q, Li J, et al. Triplet pregnancy from the transfer of two blastocysts demonstrating a twin reversed arterial perfusion sequence with a conjoined-twins pump fetus. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2017;137(2):196–7.

Mariona F, Burnett M, Zoma M. Early unexpected diagnosis of fetal life-limiting malformation;antenatal palliative care and parental decision. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;32(6):1036–43.

Meng XL, Wei Y, Zhao YY. Conjoined Twins in a Spontaneous Monochorionic Triplet Pregnancy. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131(20):2492–4.

Gao Q, Pang H, Luo H. Conjoined twins in a spontaneous monochorionic triplet pregnancy. A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(4):e24490.

Skupski DW, Streltzoff J, Hutson JM, et al. Early diagnosis of conjoined twins in triplet pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and assisted hatching. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14(8):611–5.

Goldberg Y, Ben-Shlomo I, Weiner E, et al. First trimester diagnosis of conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy after IVF and ICSI:case report. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(6):1413–5.

Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Horan C, et al. Dichorionic triplet pregnancy with the monoamniotic twin pair concordant for omphalocele and bladder extrophy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16(7):669–71.

Charles A, Dickinson JE, Watson S, et al. Diamniotic conjoined fetuses in a triplet pregnancy:an insight into embryonic topology. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2005;8(6):666–72.

Hirata T, Osuga Y, Fujimoto A, et al. Conjoined twins in a triplet pregnancy after intracytoplasmic sperm injection and blastocyst transfer: case report and review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(3):933.e9–12.

Shepherd LJ, Smith GN. Conjoined Twins in a Triplet Pregnancy:A Case Report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:235873.

Takae S, Izuchi S, Murayama K, et al. Two cases of pregnancy involving conjoined twins,with details of management after opting for live birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2011;37(10):1478–83.

Castro PT, Werner H, Araujo JE. First-trimester diagnosis of conjoined twins in a multifetal pregnancy after assisted reproduction technique using HDlive rendering. J Ultrasound. 2017;20(1):85–6.

Acknowledgements

We feel grateful for the doctors and staff who have been involved in this work. All persons that contributed to this study are listed authors and meet the criteria for authorship.

Funding

This study was supported by the Academic and Technical Leader’s Foundation of Sichuan Province (No.2017–919-25).The funding played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYL carried out the retrospective review of the case and participated in the design, writing, and organization of the manuscript. HYY conceived of the whole study, supervised the work overall, and carried out the study design and corrections of the manuscript. XDW participated in the design of the study. QH, CYD, and HL participated in the analysis of cases and the literature review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committees at the West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflict of interest regarding this paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Deng, C., Hu, Q. et al. Conjoined twins in dichorionic diamniotic triplet pregnancy: a report of three cases and literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 687 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04165-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04165-x