Abstract

Background

Smoking cessation in pregnancy has unique challenges. Health providers (HP) may need support to successfully implement smoking cessation care (SCC) for pregnant women (PW). We aimed to synthesize qualitative data about views of HPs and PW on SCC during pregnancy using COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) framework.

Methods

A systematic search of online databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL) using PRISMA guidelines. PW’s and HPs’ quotes, as well as the authors’ analysis, were extracted and double-coded (30%) using the COM-B framework.

Results

Thirty-two studies included research from 5 continents: 13 on HPs’ perspectives, 15 on PW’s perspectives, four papers included both. HPs’ capability and motivation were affected by role confusion and a lack of training, time, and resources to provide interventions. HPs acknowledged that advice should be delivered while taking women’s psychological state (capability) and stressors into consideration. Pregnant women’s physical capabilities to quit (e.g., increased metabolism of nicotine and dependence) was seldom addressed due to uncertainty about nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) use in pregnancy. Improving women’s motivation to quit depended on explaining the risks of smoking versus the safety of quit methods. Women considered advice from HPs during antenatal visits as effective, if accompanied by resources, peer support, feedback, and encouragement.

Conclusions

HPs found it challenging to provide effective SCC due to lack of training, time, and role confusion. The inability to address psychological stress in women and inadequate use of pharmacotherapy were additional barriers. These findings could aid in designing training programs that address HPs’ and PW’s attitudes and supportive campaigns for pregnant smokers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Smoking tobacco during pregnancy is an established risk factor for a range of health problems for mothers and the baby, including long term complications in childhood. Exposure to tobacco smoke in-utero increases the risk of still birth, low birth weight and small for gestational age babies [1]. Women who smoke during pregnancy are more likely to experience obstetric complications such as spontaneous abortions, placental abruption, placenta previa, premature labour, and ectopic pregnancies compared to women who don’t smoke during pregnancy [1]. Globally, 1.7% of pregnant women (PW) smoke during pregnancy [2]. Five countries namely Ireland, Uruguay, Bulgaria, Spain and Denmark have the highest rates of smoking in pregnancy ranging from 25 to 38%. Research suggests that a significant proportion of women stop smoking when they become pregnant, mainly to safeguard their baby from the harms of smoking [3]. However, worldwide, 50% of women who smoke continue to do so during pregnancy [2]. Experiencing social or economic disadvantage, particularly poverty, living in a normalized smoking environment, low access to healthcare and a highly stressful life are significant predictors of smoking during pregnancy [4]. For example, Indigenous women from developed countries, who may be exposed to all of the aforesaid, have double the smoking prevalence compared to their pregnant, non-Indigenous counterparts [5]. Other risk factors for smoking during pregnancy include being an older mother, teenage mother, multiparty, high nicotine dependence, experiencing intimate partner violence or mental health issues such as depression [4].

The health provider’s role in smoking cessation

High quality evidence suggests behavioral interventions such as counseling, feedback, and incentives increase smoking cessation rates in pregnancy [6]. Pragmatic research also suggests that nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) increases smoking cessation rates among PW, although more research to account for the higher nicotine metabolism during pregnancy and research on higher doses of NRT are needed [7]. Smoking cessation guidelines from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom recommend NRT use by PW to achieve smoking cessation if behavioral methods are not successful [7]. The onus of translating the existing smoking cessation research lies on health providers (HPs) who remain the mainstay for providing smoking cessation care to PW. HPs that care for PW come from several disciplines, including medical practitioners, midwives, and Community Health Workers. Clinical smoking cessation guidelines usually recommend a structured approach such as the 5As (Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange) or the ABC (Ask, Brief advice and Cessation support) [8] to HPs to ensure the completeness of the smoking cessation intervention. Despite these guidelines, smoking cessation interventions may be underutilized by HPs [9–11]. Additionally, there is little practical guidance for HPs such as how to weigh up the risks versus benefits of using NRT in pregnancy, and how to titrate the dosage of NRT to account for PW’s faster metabolism [7]. There is limited research about HPs’ knowledge and attitudes about providing smoking cessation care to smoking PW during their consultations [12, 13]. Given that smoking cessation in pregnancy has unique challenges, HPs may need additional training and skills for the successful implementation of smoking cessation interventions for PW.

A large number of theories and models have been proposed to explain the complex science of behavior change. The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) is a parsimonious model that takes into account multiple behavior change theories (See Fig. 1). At its center (green hub) is the COM-B model [14]. COM-B is an acronym for capability (C)- physical and psychological, Opportunity (O)- physical and social and Motivation (M)- automatic and reflective, all of which drive behavior change (B) [14]. Most behavior change interventions incorporate one or more of these behavior change principles. However, a successful intervention ideally should take all three tiers of the wheel into consideration [15]. Consequently, the COM-B and BCW can be used to analyze a behavior change intervention to identify if an intervention has used a systematic approach to achieve its desired outcomes, what mechanism of actions were operationalized and if the intervention failed, the possible reasons for its failure [15]. Intervention functions and policies are captured in the middle (red) and outer (grey) rings respectively.

This systematic review aims to synthesize published qualitative research about smoking cessation care provided by HPs to PW who smoke. The primary objective was to explore both HPs’ and PW’s perspectives on smoking cessation care using a COM-B framework with reference also to the BCW. A secondary aim was to identify intervention functions how the capability, opportunity, and motivation of HPs could be improved to provide optimum smoking cessation care during pregnancy. Intervention functions are broad categories of means by which an intervention can change behaviour. Intervention functions as described by Michie S [15] include education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement. We have highlighted intervention functions (IF) where they were apparent from the extracted data, but not for every finding.

Methods

Data sources and study selection

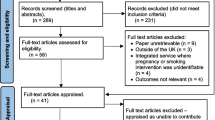

Underpinned by PRISMA guidelines, a systematic search was carried out in research databases including MEDLINE; EMBASE; PsycINFO and CINAHL until March 2020 (see Fig. 2). Keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms related to ‘Health providers,’ Search terms: “Attitudes and practices; “smoking” and; “pregnancy” were used (Supplemental file 1: Full search strategy in Medline).

Inclusion criteria

Peer-reviewed, qualitative, or mixed methods studies, written in English, were included. The topics explored were: the views of any HPs about the provision of established forms of smoking cessation care to PW (for example the 5As or smoking cessation guidelines) in any setting and papers exploring women’s views on the smoking cessation care received from their HPs. There was no restriction on publication date.

Exclusions

Studies exclusively reporting quantitative data, evaluating new programs or interventions (papers reporting qualitative data on established practices were not considered new), in non-peer reviewed journals, or only minimally covered the topic.

This review was a part of a larger review registered with PROSPERO in 2015: CRD42015029989. The quantitative data were analyzed and published separately [11].

Data extraction

The review team included a General Practitioner (GG), Public Health Physician (YBZ), Public Health Dentist (RK), Health Promotion Expert (LS), Epidemiologist (JJ), Psychologist (GRG), Gender and Health Expert (PE) and Behavioural Scientist (LT). Authors have an extensive background in tobacco cessation, epidemiology, and qualitative research. Electronic databases were searched by LS, RK, YBZ and LT, who independently screened the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles. Full-text articles were independently by two authors (YBZ, LT, JJ, GRG, LS, PE). Date range was from August 2015 to March 2020. A third author adjudicated discrepancies by mutual discussion (GG). Reference lists of the included articles were searched for additional papers and original articles thus retrieved included if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria. We only analyzed the study with available results as a part of the published manuscript and did not contact the authors for further detail. Microsoft Excel was used to record the study characteristics namely title, authors, year of publication, setting, aims, study design, methodological orientation, quotes (first-order constructs), themes and subthemes (second-order constructs), explanatory models (third-order constructs), sample size and focus of the interviews. Data were extracted by one author (LS) from the full texts of the articles, quality checked by a second author (YBZ and GRG) for twelve of the articles (45%).

Analysis

Quality assessment

Since there are very few established quality assessment tools for qualitative studies and due to the research team’s prior experience, the Hawker Quality Assessment Tool [16, 17] was used to for the quality assessment of the studies. This tool assesses studies using nine questions; potential ratings and corresponding numerical scores were good (4), fair (3), poor (2), and very poor (1). Scores for each study were totaled to give a score indicative of the overall quality of the study, ranging from a minimum of 9 points to a maximum of 36 points. Studies were classified as high quality (30–36 points); medium quality (24–29 points) or low quality (9–24 points) [17]. Initially 5% of randomly selected papers were assessed by LS, YBZ and GB. Where the reviewers assigned different domain scores to a study, the differences were discussed among co-authors with GG adjudicating to resolve the difference to arrive at a final domain score. The rest of the papers were then scored by LS informed by the discussion and adjudication.

COM-B analysis

For this review, the BCW [14, 18] and the COM-B model [14, 18] were used to analyze the smoking cessation care delivered by HPs or received by PW who smoked. We coded for all aspects of care delivery from the viewpoint of HPs and women, including barriers and facilitators as well as the actual care delivered. First-order constructs (quotes) from HPs and PW and second-order constructs (interpretations by authors or themes) were extracted line by line from the included papers and coded using the COM-B framework and its sub-components. Quotes were multi-coded if they reflected more than one component or subcomponent of the COM-B framework. LS completed coding; 30% of the papers were double coded to ensure consistency (JJ and RK). GG reviewed the coding to ensure consistency. BCW Policy categories (grey zone BCW- Fig. 1) and Intervention functions (red zone BCW- Fig. 1) were selected by GG and RK to describe which intervention functions and policy measures (aimed at HPs and/or PW) were indicated by the data, according to the BCW. The data was synthesized by creating a narrative within each theme within the COM-B framework. Coders (JJ, RK and LS) continuously reflected on their own inherent biases. In particular, the researchers were aware during the data collection and analysis process of their backgrounds in smoking cessation and intervention delivery might bias the interpretation of findings. Assumptions while analyzing the data were discussed with GG for arbitration.

Results

This review included 32 qualitative and mixed methods studies [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]: 13 focused exclusively on the HPs’ perspectives [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30, 51], 15 exclusively on PW’s perspectives [31, 33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,44,45,46], while four papers included both [47,48,49,50]. Twenty studies were conducted in Europe [19, 21, 22, 25,26,27, 30, 31, 34, 36, 38, 39, 41,42,43,44,45, 47, 49, 51], eight in the Oceania region [20, 24, 29, 33, 37, 40, 46, 50], two in the USA [23, 35] and one each in South America [48] and Africa [28]. HPs included doctors, nurses, midwives, Aboriginal Health Workers, pharmacists and other allied HPs. Please see Supplementary file 2 for the characteristics of included studies.

Quality assessments

Seventeen studies were rated as high quality [19, 21, 24,25,26, 29, 33,34,35,36, 38, 41, 44, 45, 47, 50, 51], 12 as medium quality [20, 23, 27, 28, 31, 37, 40, 42, 43, 46, 48, 49] while 3 studies [22, 30, 39] were of low quality. Please see Table 1 for the quality assessment of included studies.

Qualitative COM-B analysis

Sub-headings of Capability, Opportunity and Motivation, and their subcomponents were used to either group results into smoking cessation care provided by HPs to PW or received by PW. Intervention functions, the range of functions within an intervention that support behaviour change and Policy categories from the BCW [14] (i.e., the middle (red) and outer (grey) rings) denoted as “IF” and “P” in brackets. Please see Table 2 for representative quotes related to each COM-B theme.

Physical capability

HPs’ physical capabilities to provide smoking cessation advice and interventions in pregnant smokers are not relevant, as most HPs are physically capable of achieving this end. However, this category touches on PW’s physical capability to quit smoking, as many may experience physical dependence. PW stated that HP did not sufficiently assist them in dealing with their physical dependence [33, 45]. Because this concerns a HP’s psychological capability to aid PW in that way, we have placed it in that section.

Psychological capability

This theme explored HPs’ psychological capabilities to provide effective quit smoking advice to their clients as well as how HPs addressed the psychological capabilities of their clients for quitting smoking.

HPs’ knowledge about providing smoking cessation interventions was a significant factor affecting the delivery of smoking cessation advice to their clients. HPs believed that greater knowledge about providing smoking cessation interventions might help them provide better smoking cessation care to PW who smoke (IF – education) [23, 49]. Lack of knowledge about providing smoking cessation interventions sometimes led to low self-efficacy in HPs to change the behavior of their pregnant clients who smoke [19–24, 27, 48]. This also supports the issue of HPs lack of knowledge about NRT added to the issue of HPs not being able to provide effective quite smoking advice.

Developing sensitivity towards PW’s psychological state was of paramount importance to the success of the smoking cessation intervention by the HPs and a known factor affecting the psychological capability of PW to quit smoking [41]. HPs acknowledged that PW, trying to quit smoking, might not be able to do so successfully due to socio-economic stress and resultant psychological challenges [23, 37, 50].

In such cases, some HPs utilized their psychological skills to help evoke feelings of control and empowerment in PW [28]. This may be achieved by providing practical stop smoking strategies that were easy to follow (IF - training) and hence more likely to be successful [19]. However, some HPs lacked training (IF -education and training) to address smoking in PW, especially with women who were stressed, had unsuccessful quit attempts or did not want to quit [23, 49, 25]. Stress was detrimental to PW, and in rare instances, HPs encouraged PW to continue smoking to avoid the stress attributed to quitting attempts [36, 38, 42, 51, 48]. Communicating the best health advice (IF - education) without making the PW feel guilty, while also trying to maintain a congenial relationship (IF -enablement) with their client, was often challenging for the HPs [19, 22, 24, 29, 30, 35, 42, 48, 52, 53]. Some HPs overcame this dilemma by recommending cutting down to reduce smoking-related harms rather than quitting, perhaps potentially preserving the relationship with their client (IF – enablement) [23, 24, 27, 29, 33, 40, 43, 46, 48, 53].

Although NRT is known to improve the physical capability of smokers to quit by reducing withdrawal symptoms, NRT was considered controversial by HPs who were reluctant to prescribe it or did not offer it frequently (IF - education) [22, 24, 27, 29, 33, 37]. Inadequate institutional policies and guidelines contributed to suboptimal use of NRT (e.g., not prescribing NRT to PW unless they have had a failed unassisted quit attempt) (P– guidelines) [22, 24, 27, 48]. Lack of knowledge among HPs affected the motivation of HPs to prescribe NRT, potentially contributing to continued smoking among PW [22, 29].

Skepticism about NRT was quite prevalent among PW [22, 31–34]. Widespread uncertainty about NRT among PW may indicate a need for a more detailed and comprehensive conversation during the consultation about NRT use to address doubts and concerns about the potential harms of NRT versus the benefits, although the HPs were not always successful in this endeavor (IF - enablement) [31–34].

HPs who had never smoked found it difficult to empathize with their pregnant clients who smoked [49]. HPs who themselves smoked hardly provided any smoking cessation counseling [52]. PW corroborated that HPs who smoked did not encourage them to quit or were not insistent enough [35, 52, 53]. For example, PW states this in McLeod, et al. [53]: “My specialist he smokes so (he) does not advocate giving up smoking.”.

In contrast, HPs who were ex-smokers sometimes acted as role models for the PW to quit smoking (IF – modeling): “I tell them that I did it so they can jolly well do it too… because I’ve smoked” McLeod, et al. [53]. HPs who themselves were ex-smokers were perceived as less judgmental (IF - enablement) and more understanding of PW’s smoking.

HPs reported PW becoming defensive if smoking cessation consultations evoked stigmatizing feelings of ignorance, guilt, and irresponsibility [24, 49, 50]. Although smoking cessation advice from HPs was expected and acceptable [43, 53, 54]. some PW resisted counselling when HPs initiated a dialogue about smoking and may counter HP advice with anecdotes and arguments that contested the smoking cessation narrative of HPs [27, 28, 35, 51, 45, 48, 50].

However, this does not necessarily prevent HP from deliberately using persuasion (IF - persuasion). Some PW supported HPs using ‘shock tactics’ to get the message of smoking cessation through to them [35, 42].

Some HPs considered providing smoking cessation advice to PW who were stressed to be risky in case their advice could have the opposite effect [38]. Conversely, some PW described their experiences of feeling pressured, stigmatized, and sometimes intimidated by the HPs for being a PW who smokes [35, 37]. Monetary compensation for quitting was generally not considered acceptable by both HPs and PW, as quitting smoking was considered to be linked to PW’s intrinsic value and self-worth rather than an extrinsic reward [36].

HP training in smoking cessation emerged as a distinct facilitator that increased the psychological capability of HPs to support smoking cessation in PW or refer them to other HPs who can offer smoking cessation advice [49]. Developing specific skills, such as motivational interviewing or how to discuss cessation while the PW are trying to quit, was especially desired [24, 29]. Some HPs implied that they are only able to provide very rudimentary counseling regarding smoking and its harmful effects on the fetus.

However, the lack of training opportunities was widespread [22, 29, 48, 52], and some HPs had not had any training at all [22, 29, 52]. These lacunae were specifically in the domains of asking, assessing, and advising about smoking cessation in a way that does not offend or alienate pregnant clients [29]. HPs wanted smoking cessation training to be ongoing and training content updated frequently to keep up with the new guidelines and research (IF – training; P – guidelines) [23, 48].

PW complained that some HPs often asked about their smoking status but never provided any practical support to help them quit pointing towards a lack of skills for providing holistic smoking cessation care [33, 40, 43, 49, 54].

Physical opportunity

This theme described opportunities afforded to HPs by their physical environment for providing smoking cessation care to PW, and opportunities that PW reported were provided to them or were lacking from HP for smoking cessation care.

Some PW complained that they were not adequately informed about the harmful effects of smoking by their HPs, nor were encouraged on their attempts to cut down or quit smoking [46, 48, 49].

Time for HPs to provide smoking cessation support was limited, as were the resources to educate PW [22, 27, 35, 45, 48, 49, 52]. HPs (and sometimes PW) commonly felt they did not have enough time to provide adequate assistance to help PW quit, or that motivating PW to quit would be a waste of time (automatic motivation) [22–24, 27, 45, 48, 52].

HPs often integrated quit smoking discussions with physical examinations to save time. Providing group quit smoking information sessions (IF -environmental restructuring) was suggested as a way to save time. HPs suggested that the waiting time before the consultations could be used to show quit smoking videos to PW and their partners, saving time during the consultation (IF - environmental restructuring) and motivating PW to quit (IF = persuasion) [26, 48]. However, HPs went further to suggest that pressure (IF - coercion) may be used to force PW to watch and confirm viewing the content [35].

Counseling strategies, such as detailed and structured protocols, saved time and were desired by HPs [24, 50]. These resources could also enhance their psychological capability by increasing knowledge and confidence in delivering smoking cessation interventions. However, some HPs highlighted that there were no clear guidelines or pathways (P- guidelines) in their institution on providing smoking cessation assistance to PW [22, 27, 48].

In some instances, informational resources such as pamphlets, educational videos, and other self-help material were not readily available to HPs (despite PWs wanting to use them), making it difficult for them to provide smoking cessation health education specific to PW (P - communication/marketing) [23, 28, 48].

HPs and PW discussed different modes of delivering quit smoking advice. Face to face delivery was considered the most successful [36]. Electronic means of communication such as telephone and email were thought to have a role by sending reminders or encouragement in between face to face appointments, thus improving PW’s reflective motivation and psychological capability to quit (P– service provision) [36]. HPs believed that smoking cessation advice should not overly depend on the traditional medical model of health information provision but rather be conveyed creatively through a wide array of resources, which may be more persuasive and motivating (reflective motivation for PW) [22, 36]. Along with face to face smoking related discussions with their doctors, midwives and other office staff, PW were open to seeing brochures, posters and other health promotional material in the doctor’s office, which they thought provided additional information and motivated them to discuss smoking with their HP (physical opportunity; IF - environmental restructuring; P- communication) [43, 48, 54].

Social opportunity

This theme explored interpersonal influences, social factors, and opportunities available to HPs for providing smoking cessation support to PW.

HPs realized that the baby’s birth could be a significant opportunity for smoking cessation as PW have innate instincts to protect the baby, and this could motivate PW to stop smoking. Hence it was considered important to start a dialogue about smoking even if HPs detected a reluctance to talk about smoking in their clients [22]. A supportive, trustful, and a respectful relationship with the PW was considered paramount to a successful quit smoking intervention by the HPs (IF - enablement) [19, 29, 30, 48, 49, 53].

HPs believed that it was necessary to reduce social stigma associated with smoking and make smoking cessation advice non-judgmental, empathetic, and sensitive to PW’s needs and their environmental contexts (IF – enablement) [22, 28, 30, 36, 41].

In some close-knit communities, such as among Aboriginal populations, PW preferred that smoking cessation advice be delivered by Elders rather than the HPs as the Elders were more familiar with the PW and their circumstances (P – service provision) [33].

Social and peer support were considered central to motivating PW to quit and stay quit, and the role of HPs in facilitating such support [19, 22, 31]. According to some participants (PW), HPs provided social support by continual encouragement to quit [36, 44, 46]. PW who stopped smoking while pregnant, often relapsed when the baby was born, mostly due to various life stressors [23, 53]. HPs stressed the importance of social support and continued health promotion for PW to quit smoking and stay quit [19, 31, 53].

Opportunities to deliver quit smoking advice in the form of group sessions emerged as a preferred method of promoting smoking cessation and improving motivation among PW [33, 35, 36]. Structured addiction support meetings along the lines of ‘Alcoholics Anonymous’ and buddy systems were also considered useful for providing social support during a quit attempt [22, 35, 36].

Some HPs advocated group smoking cessation interventions for PW early in their pregnancy stages to save time (physical opportunity) or while performing pre-natal consultations [36, 39, 20].

PW concurred that an experiential opportunity involving witnessing or hearing about other people’s lived experiences of the effects of smoking during pregnancy would encourage them to stop smoking [35].

Automatic motivation

This theme explored the factors that affect HP’s innate emotional reactions, impulses, and inhibitions related to providing smoking cessation support to PW. Identification of vulnerabilities such as stress and depression in PW acted as a deterrent to the provision of smoking cessation care by the HPs [23, 36, 38]. HPs instinctively tried not to offend their clients and make them feel supported.

HPs additionally considered it important to improve the motivation and knowledge of PW about potential smoking-related harms to the baby as an integral objective of smoking cessation care [23]. To this end, some HPs presented or wanted to present gruesome imagery (IF - persuasion) to accentuate the automatic motivation of PW to quit smoking [19, 35]. Identification of PW’s motivation to quit and reinforcing it was considered more successful than introducing new motivations by the HPs [35].

Pregnant women being praised for efforts to quit smoking, not being judged for smoking, and not made to feel guilty about smoking by HPs (IF - enablement) were significant automatic motivators for the PW to continue trying to quit smoking [26, 36] However, this was not always achieved and sometimes PW felt that they were being pushed or nagged to quit smoking [37]. Reassurance from HPs appeared to pacify PW’s fears about attempting to quit smoking.

Assumptions about the clients not wanting to quit smoking and skepticism about their chances to succeed in becoming smoke-free often informed whether or not the HPs provided smoking cessation care [29, 48, 20].

Smoking cessation consultations were often labeled “difficult” [49] HPs feared evoking pain, guilt, and shame in PW by discussing their smoking, and hence, the topic of smoking cessation [24, 45, 49]. HPs may instinctively avoid the issue altogether.

Reflective motivation

This theme explored the processes and beliefs of HPs that promoted provision of smoking cessation care for their patients. Some health providers were intrinsically motivated to provide smoking cessation counseling and considered it their duty to assist PW to quit smoking [24, 26, 52]. On the other hand, others felt that it was not their role to provide smoking cessation interventions to their clients [29].

Role confusion affected HPs motivation to provide adequate smoking cessation. Clinicians reported they were not responsible for addressing smoking cessation with PW and it was better suited to come from smoking cessation specialists, GPs or midwives during pre-natal clinics [29, 55]. However, midwives described situations where the topic of smoking cessation was avoided, or they did not perceive it to be their responsibility either [27].

Several HPs expressed that they only considered providing smoking cessation assistance to PW if, during the consultation, they inferred that the PW wanted to quit smoking [22, 52].

HPs believed that success of a smoking cessation intervention depended on the inherent motivation of their clients to quit: “if they don’t want to give up you’re bashing your head against a brick wall” [29]. HPs who provided information about the harmful effects of smoking and quitting methods to PW patently empowered them with the knowledge to motivate an effective quit attempt.

Discussion

This systematic review explored qualitative research from 32 studies (spanning more than 20 years) across the world about the reported experiences of PW and HPs during smoking cessation care. The analysis of the qualitative themes used the COM-B behavior change model’s Behaviour Change Wheel [15]. This model has been previously used to understand different behaviors such as NRT use [56], barriers and facilitators of health behaviors [57, 58] and uptake of health services [59]. Almost all studies included in this review were rated as high to medium quality, thus indicating greater reliability of the results.

This review found that there was a lack of key intervention functions and policies that could support health professionals provide good smoking cessation care. Smoking cessation interventions aimed at improving the physical capabilities of PW who smoke (i.e., to aid PW in dealing with the physical addiction to nicotine), were rarely described or addressed. Nicotine metabolism increases significantly during pregnancy [60], making nicotine withdrawal much more pronounced. Thus, HPs who are unable to improve the physical capability of PW through offering NRT may not be successful in enabling smoking cessation among their clients [61, 62]. Some PW may be wary of using NRT due to fears of nicotine harming their baby and thus prefer to continue smoking, or quit without pharmacological support. This lack of enthusiasm by both parties towards using NRT has been demonstrated in other reviews [63] and could significantly hamper the physical capability of PW to overcome their nicotine withdrawal symptoms and quit smoking successfully.

HPs may hold paternalistic beliefs that expecting PW who smoke to quit was too challenging for them. Literature suggests that HPs who are not confident of their counseling techniques will often adopt paternalistic approaches as opposed to HPs who take a patient-centered approach and act as friends and carers to their clients [64]. Stress among PW and lack of skills among HPs to manage it may promote HPs to recommend ‘cutting’ down rather than complete abstinence. Ingall et al. (2010) [65] similarly found that HPs who were smokers may support PW to cut down rather than quit completely. Despite some clients perceiving a recommendation to cut down as supportive [66], the latest evidence and smoking cessation guidelines conclude that complete abstinence is the best practice [67]. Potential benefits from smoking reduction are highly questionable [68]. Our previous research suggests that ‘cutting-down’ to assist towards cessation may delay PW from getting the benefits for their baby that could be achieved by complete abstinence [33]. A less prescriptive and more patient-centered approach may be more useful for behavior change [69].

Lack of time, training, and resources along with role ambivalence among HPs contribute to many missed opportunities to counsel PW about smoking cessation. Negative attitudes, lack of knowledge resulting in limited confidence to discuss smoking cessation, and perceptions of the topic as unpleasant and intrusive, are common barriers to the provision of smoking cessation care to PW who smoke. These factors combine to rob HPs of a significant social opportunity to address smoking among their pregnant clients [70]. Pregnant women who smoke are not consistently offered health information related to smoking and its adverse effects, smoking cessation advice, nor provided referrals [24, 71, 72]. Lack of opportunities for training in smoking cessation has been raised by other authors, similarly to our study [13, 73].

The results of our review align with themes raised by systematic reviews by Baxter, Everson-Hock, Messina, Guillaume, Burrows and Goyder [74] (23 papers) and Bauld, et al. [63] (9 studies) on perspectives of HPs on the delivery of smoking cessation care to PW. Baxter, et al. [74] highlighted HPs’ lack of interpersonal and counseling skills and skepticism towards their effectiveness in providing smoking cessation care, although unlike the present review, there was only limited reference in the Baxter’s review about NRT. Our findings confirm the results of Bauld, et al. [63] who found that there was a need to improve smoking cessation knowledge and confidence among HPs. Best strategies to support women identified in Bauld, et al. [63] review were routine CO screening, behavioral support, and access to pharmacotherapy. Pregnant women can under-report their smoking behaviours [75]. CO screening could better identify smoking behaviours among pregnant women allowing HP to provide better SCC support. In contrast to Baxter, et al. [74], the present review also examined the perspectives of PW about the smoking cessation care provided to them by HPs. Analysis of both perspectives through the lens of BCW can inform more effective policies and interventions.

Strengths and weaknesses

All studies that fit the selection criteria were included in the review irrespective of quality making it the most far-reaching review of HPs’ and PW’s perspectives on smoking cessation care given and received during pregnancy. A strength of this study is that it advanced the use of the COM-B in a unique way by juxtaposing HP and women’s voices within the categories of the BCW. This review simultaneously analyzed both the perspectives of PW about receiving HP smoking cessation care and the HPs providing smoking cessation care to get a complete picture of the interaction between the PW and their HPs, the differences, and similarities. We only included studies published in English, and hence, the generalization of results to a broader range of non-English speaking countries is limited. This was also a global systematic review and hence local and cultural contexts have not been studied in detail. The main reason for this is majority of the studies were conducted in high-income countries which have similar health systems. Moreover, our aim was to look for commonalities across the globe as opposed to determining which attitudes were more prevalent in different countries.

Implications for practice, policy, and research

There is a need to improve the knowledge and capabilities of HPs to provide effective smoking cessation care to their pregnant clients. This review could guide interventions to improve HPs capability and motivation to deliver smoking cessation interventions to PW along with encouraging policies to improve opportunities for HPs to deliver these interventions. This would include making available to HPs ongoing training opportunities, supplemented with clear guidelines, and effective resources. Secondly, smoking cessation training should include effective techniques to manage the clients’ stress and other negative mental effects, since stress and depression in PW are major deterrents to the provision of smoking cessation care [76]. Training could address HPs’ concerns that smoking cessation counseling will adversely impact their relationship with their pregnant clients, along with boosting their confidence to address smoking cessation care. Thirdly, policy gaps were identified by health professionals. Communication and guideline policies in health institutions and services, in particular, formulating smoking cessation policy with staff would improve SCC outcomes. Asking about smoking cessation status and the provision of smoking cessation advice should be normalized throughout the service and mandatorily undertaken by all HPs so that there is no role confusion about smoking intervention delivery. Fourthly, since many HPs hesitate to suggest NRT for quitting due to limited research in this field, well designed randomized controlled trials are required to strengthen the evidence base with regards to effectiveness and safety of higher doses of NRT in pregnancy [77].

Conclusion

This study provided an in-depth analysis of smoking cessation care offered by HPs to PW who smoke. The results of this study are useful in identifying barriers to delivery of smoking cessation care by HPs as well as designing effective smoking cessation interventions that are most likely to be accepted by PW and implemented by HPs.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Change history

08 September 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04094-9

Abbreviations

- HP:

-

Health Provider

- PW:

-

Pregnant woman/women-

- SCC:

-

Smoking Cessation Care

- COM-B:

-

Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour

- NRT:

-

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

- 5As:

-

Ask, Assess, Advise, Assist and Arrange

- ABC:

-

Ask, Brief advice and Cessation support

- BCW:

-

Behaviour Change Wheel

- IF:

-

Intervention Function

- P:

-

Policy categories

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- MESH:

-

Keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MESH)

References

Gould GS, Havard A, Lim LL, Kumar R. Exposure to tobacco, environmental tobacco smoke and nicotine in pregnancy: a pragmatic overview of reviews of maternal and child outcomes, effectiveness of interventions and barriers and facilitators to quitting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2034. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17062034.

Lange S, Probst C, Rehm J, Popova S. National, regional, and global prevalence of smoking during pregnancy in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(7):e769–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30223-7.

Levis DM, Stone-Wiggins B, O'Hegarty M, Tong VT, Polen KN, Cassell CH, et al. Women's perspectives on smoking and pregnancy and graphic warning labels. Am J Health Behav. 2014;38(5):755–64. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.38.5.13.

Riaz M, Lewis S, Naughton F, Ussher M. Predictors of smoking cessation during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2018;113(4):610–22.

Gould GS, Patten C, Glover M, Kira A, Jayasinghe H. Smoking in pregnancy among indigenous women in high-income countries: a narrative review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(5):506–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntw288.

Chamberlain C, O'Mara-Eves A, Porter J, Coleman T, Perlen SM, Thomas J, et al. Psychosocial interventions for supporting women to stop smoking in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2(2):CD001055.

Bar-Zeev Y, Lim LL, Bonevski B, Gruppetta M, Gould GS. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Med J Aust. 2018;208(1):46–51. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.00446.

McRobbie H, Bullen C, Glover M, Whittaker R, Wallace-Bell M, Fraser T. New Zealand guidelines. N Z Med J. 2008;121(1276):57–70.

Jordan TR, Dake JR, Price JH. Best practices for smoking cessation in pregnancy: do obstetrician/gynecologists use them in practice? J Women's Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(4):400–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.15.400.

Mejia R, Martinez VG, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ. Physician counseling of pregnant women about active and secondhand smoking in Argentina. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(4):490–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016341003739567.

Gould GS, Twyman L, Stevenson L, Gribbin GR, Bonevski B, Palazzi K, et al. What components of smoking cessation care during pregnancy are implemented by health providers? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e026037. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026037.

Passey ME, D'Este CA, Sanson-Fisher RW. Knowledge, attitudes and other factors associated with assessment of tobacco smoking among pregnant Aboriginal women by health care providers: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):165. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-165.

Okoli CTC, Greaves L, Bottorff JL, Marcellus LM. Health care providers' engagement in smoking cessation with pregnant smokers. Journal of obstetric, gynecologic, and neonatal nursing : JOGNN. 2010;39(1):64–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2009.01084.x.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. 1st ed. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(9):1284–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302238251.

Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, Neary D, Clayton S, Wright K, et al. Crime, fear of crime and mental health: Synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence, Crime, fear of crime and mental health: synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Volume 2, edn. Southampton (UK); 2014.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions. Great Britain; 2014.

Abrahamsson A, Springett J, Karlsson L, Håkansson A, Ottosson T. Some lessons from Swedish midwives’ experiences of approaching women smokers in antenatal care. Midwifery. 2005;21(4):335–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2005.02.001.

Reeks R, Padmakumar G, Andrew B, Huynh D, Longman J. Barriers and enablers to implementation of antenatal smoking cessation guidelines in general practice. Australian J Primary Health. 2020;26(1):81–7. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY18195.

Thomson R, McDaid L, Emery J, Naughton F, Cooper S, Dyas J, Coleman T. Knowledge and Education as Barriers and Facilitators to Nicotine Replacement Therapy Use for Smoking Cessation in Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study with Health Care Professionals. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019:16;1814.

Bull L. Smoking cessation intervention with pregnant women and new parents (part 2): a focus group study of health visitors and midwives working in the UK. J Neonatal Nurs. 2007;13(5):179–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnn.2007.07.003.

Aquilino ML, Goody CM, Lowe JB. WIC providers’ perspectives on offering smoking cessation interventions. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2003;28(5):326–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005721-200309000-00013.

Bar-Zeev Y, Skelton E, Bonevski B, Gruppetta M, Gould GS. Overcoming Challenges to Treating Tobacco use during Pregnancy - A Qualitative study of Australian General Practitioners Barriers. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2019;19(1) (no pagination)(61).

Thomson R, McDaid L, Emery J, Phillips L, Naughton F, Cooper S, et al. Practitioners' Views on Nicotine Replacement Therapy in Pregnancy during Lapse and for Harm Reduction: A Qualitative Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(23).

Reardon R, Grogan S. Talking about smoking cessation with pregnant women: exploring midwives' accounts. Br J Midwifery. 2016;24(1):38–42. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2016.24.1.38.

De Wilde K, Tency I, Steckel S, Temmerman M, Boudrez H, Maes L. Which role do midwives and gynecologists have in smoking cessation in pregnant women?–a study in Flanders, Belgium. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. 2015;6(2):66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2014.12.002.

Everett K, Odendaal H, Steyn K. Doctors' attitudes and practices regarding smoking cessation during pregnancy. S Afr Med J. 2005;95(5):350-4.

Longman JM, Adams CM, Johnston JJ, Passey ME. Improving implementation of the smoking cessation guidelines with pregnant women: how to support clinicians? Midwifery. 2018;58:137–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.12.016.

Randall S. Midwives' attitudes to smoking and smoking cessation in pregnancy. Br J Midwifery. 2009;17(10):642–6. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2009.17.10.44463.

Ashwin C, Watts K. Exploring the views of women on using nicotine replacement therapy in pregnancy. Midwifery. 2010;26(4):401–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2008.11.001.

Aquilino ML, Goody CM, Lowe JB: WIC providers’ perspectives on offering smoking cessation interventions. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing 2003, 28(5):326-332.

Bovill M, Gruppetta M, Cadet-James Y, Clarke M, Bonevski B, Gould GS. Wula (voices) of Aboriginal women on barriers to accepting smoking cessation support during pregnancy: findings from a qualitative study. Women and Birth. 2018;31(1):10–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.006.

Bowker K, Campbell KA, Coleman T, Lewis S, Naughton F, Cooper S. Understanding pregnant smokers’ adherence to nicotine replacement therapy during a quit attempt: a qualitative study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;18(5):906–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntv205.

Britton GR, Collier R, McKitrick S, Sprague LM, Rhodes-Keefe J, Feeney A, et al. CE: original research the experiences of pregnant smokers and their providers. AJN Am J Nurs. 2017;117(6):24–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000520228.66868.ae.

Butterworth SJ, Sparkes E, Trout A, Brown K. Pregnant smokers’ perceptions of specialist smoking cessation services. J Smok Cessat. 2014;9(2):85–97. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsc.2013.25.

Gamble J, Grant J, Tsourtos G. Missed opportunities: a qualitative exploration of the experiences of smoking cessation interventions among socially disadvantaged pregnant women. Women and Birth. 2015;28(1):8–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2014.11.003.

Goszczyńska E, Knol-Michałowska K, Petrykowska A. How do pregnant women justify smoking? A qualitative study with implications for nurses’ and midwives’ anti-tobacco interventions. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(7):1567–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12949.

Haslam C, Draper E. A qualitative study of smoking during pregnancy. Psychol Health Med. 2001;6(1):95–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/713690228.

Hotham ED, Atkinson ER, Gilbert AL. Focus groups with pregnant smokers: barriers to cessation, attitudes to nicotine patch use and perceptions of cessation counselling by care providers. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2002;21(2):163–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/09595230220139064.

Howard LM, Bekele D, Rowe M, Demilew J, Bewley S, Marteau TM. Smoking cessation in pregnant women with mental disorders: a cohort and nested qualitative study. BJOG. 2013;120(3):362–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12059.

Haugland S, Haug K, Wold B. The pregnant smoker's experience of ante-natal care—results from a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1996;14(4):216–22. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813439608997088.

Lendahls L, Öhman L, Liljestrand J, Håkansson A. Women's experiences of smoking during and after pregnancy as ascertained two to three years after birth. Midwifery. 2002;18(3):214–22. https://doi.org/10.1054/midw.2002.0312.

Naughton F, Eborall H, Sutton S. Dissonance and disengagement in pregnant smokers: a qualitative study. J Smok Cessat. 2013;8(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/jsc.2013.4.

Petersen Z, Nilsson M, Everett K, Emmelin M. Possibilities for transparency and trust in the communication between midwives and pregnant women: the case of smoking. Midwifery. 2009;25(4):382–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2007.07.012.

Wigginton B, Lee C. A story of stigma: Australian women’s accounts of smoking during pregnancy. Crit Public Health. 2013;23(4):466–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2012.753408.

Rezk-Hanna M, Sarna L, Petersen AB, Wells M, Nohavova I, Bialous S. Attitudes, barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation among central and eastern European nurses: a focus group study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;35:39–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2018.04.001.

Colomar M, Tong VT, Morello P, Farr SL, Lawsin C, Dietz PM, et al. Barriers and promoters of an evidenced-based smoking cessation counseling during prenatal care in Argentina and Uruguay. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(7):1481–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1652-3.

Herberts C, Sykes C. Midwives’ perceptions of providing stop-smoking advice and pregnant smokers’ perceptions of stop-smoking services within the same deprived area of London. J Midwifery Women’s Health. 2012;57(1):67–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00072.x.

Wood L, France K, Hunt K, Eades S, Slack-Smith L. Indigenous women and smoking during pregnancy: knowledge, cultural contexts and barriers to cessation. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(11):2378–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.024.

Naughton F, Hopewell S, Sinclair L, McCaughan D, McKell J, Bauld L. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation in pregnancy and in the post-partum period: the health care professionals' perspective. Br J Health Psychol. 2018;23(3):741–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12314.

Oude Wesselink SF, Stoopendaal A, Erasmus V, Smits D, Mackenbach JP, Lingsma HF, et al. Government supervision on quality of smoking-cessation counselling in midwifery practices: a qualitative exploration. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):270. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2198-z.

McLeod D, Benn C, Pullon S, Viccars A, White S, Cookson T, et al. The midwife's role in facilitating smoking behaviour change during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2003;19(4):285–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-6138(03)00038-X.

McCurry N, Thompson K, Parahoo K, O'Doherty E, Doherty A-M. Pregnant women's perception of the implementation of smoking cessation advice. Health Educ J. 2002;61(1):20–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/001789690206100103.

De Wilde K, Tency I, Steckel S, Temmerman M, Boudrez H, Maes L. Which role do midwives and gynecologists have in smoking cessation in pregnant women?–a study in Flanders, Belgium. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(2):66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2014.12.002.

Herbec A, Tombor I, Shahab L, West R. "if I'd known …"-a theory-informed systematic analysis of missed opportunities in Optimising use of nicotine replacement therapy and accessing relevant support: a qualitative study. Int J Behav Med. 2018;25(5):579–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-018-9735-y.

Russell CG, Taki S, Azadi L, Campbell KJ, Laws R, Elliott R, et al. A qualitative study of the infant feeding beliefs and behaviours of mothers with low educational attainment. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-016-0601-2.

Grant A, Morgan M, Mannay D, Gallagher D. Understanding health behaviour in pregnancy and infant feeding intentions in low-income women from the UK through qualitative visual methods and application to the COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation-behaviour) model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):56. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-2156-8.

McDonagh LK, Saunders JM, Cassell J, Curtis T, Bastaki H, Hartney T, et al. Application of the COM-B model to barriers and facilitators to chlamydia testing in general practice for young people and primary care practitioners: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):130. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0821-y.

Bowker K, Lewis S, Coleman T, Cooper S. Changes in the rate of nicotine metabolism across pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2015;110(11):1827–32.

Einarson A, Riordan S. Smoking in pregnancy and lactation: a review of risks and cessation strategies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(4):325–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0609-0.

Hickson C, Lewis S, Campbell KA, Cooper S, Berlin I, Claire R, et al. Comparison of nicotine exposure during pregnancy when smoking and abstinent with nicotine replacement therapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2019;114(3):406–24.

Bauld L, Graham H, Sinclair L, Flemming K, Naughton F, Ford A, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in pregnancy and following childbirth: literature review and qualitative study. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England). 2017;21(36):1–158.

Everett-Murphy K, Paijmans J, Steyn K, Matthews C, Emmelin M, Peterson Z. Scolders, carers or friends: south African midwives' contrasting styles of communication when discussing smoking cessation with pregnant women. Midwifery. 2011;27(4):517–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2010.04.003.

Ingall G, Cropley M. Exploring the barriers of quitting smoking during pregnancy: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Women Birth. 2010;23(2):45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2009.09.004.

Flemming K, McCaughan D, Angus K, Graham H. Qualitative systematic review: barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation experienced by women in pregnancy and following childbirth. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71(6):1210–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12580.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Supporting smoking cessation: A guide for health professionals. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2014.

Kumar R, Gould GS. Tobacco harm reduction for women who cannot stop smoking during pregnancy-a viable option? JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):615–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0902.

Martin MW, Martin SL, Ross RH. Health care providers’ smoking cessation advice among pregnant smokers. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2010;4(3):253–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827610361437.

Vogt F, Hall S, Marteau TM. General practitioners' and family physicians' negative beliefs and attitudes towards discussing smoking cessation with patients: a systematic review. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2005;100(10):1423–31.

Castrucci BC, Culhane JF, Chung EK, Bennett I, McCollum KF. Smoking in pregnancy: patient and provider risk reduction behavior. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12(1):68–76. https://doi.org/10.1097/00124784-200601000-00013.

Perlen S, Brown SJ, Yelland J. Have guidelines about smoking cessation support in pregnancy changed practice in Victoria, Australia? Birth. 2013;40(2):81–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12036.

McCullough B, Walker S, Lee J, Prady S, Small N. Improving clinical practice by better use of data: smoking in pregnancy. Br J Midwifery. 2013;21(2):118–22. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjom.2013.21.2.118.

Baxter S, Everson-Hock E, Messina J, Guillaume L, Burrows J, Goyder E. Factors relating to the uptake of interventions for smoking cessation among pregnant women: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):685–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntq072.

Tong VT, Althabe F, Aleman A, Johnson CC, Dietz PM, Berrueta M, et al. Accuracy of self-reported smoking cessation during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(1):106–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12532.

Guassora AD, Gannik D. Developing and maintaining patients’ trust during general practice consultations: the case of smoking cessation advice. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(1):46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.05.003.

Coleman T, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, Cooper SE, Leonardi-Bee J. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD010078.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of Gabrielle Gribbin in partaking in the search and screening of abstracts and full text of articles. Also contributing to the quality check of the articles.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant from Hunter Cancer Research Alliance, Australia. The funding body had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to aspects of the analysis and interpretation of the data. RK, LS and GG prepared the manuscript and all authors contributed to revision of the paper and approved the submitted version. GG oversaw all aspects of the study and article write-up of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

YBZ received personal fees from Novartis NCH and Pfizer Israel LTD outside the submitted work. No other authors have competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: a couple of minor changes were made in the Abstract and Results section, including reference citations. In the reference list, author names ‘Michie SAL, West R’ were amended to ‘Michie S, Atkins L, West R’.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search terms for literature review 31/07/2015.

Additional file 2.

The characteristics of included studies. This of included studies including study first author and year, country, study focus and number of participants, study aim(s) and summary of results.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar, R., Stevenson, L., Jobling, J. et al. Health providers’ and pregnant women’s perspectives about smoking cessation support: a COM-B analysis of a global systematic review of qualitative studies. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 550 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03773-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03773-x