Abstract

Background

Approximately one in five pregnant women have obesity. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of antenatal, intrapartum, and perinatal complications, but many women with obesity have uncomplicated pregnancies. At a time where maternity services are advocating for women to make informed choices, knowledge of the chance of having an uncomplicated (healthy) pregnancy is essential. The objective of this study was to calculate the rate of uncomplicated pregnancy in women with obesity and evaluate factors associated with this outcome.

Methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted using the Ontario birth registry dataset in Canada (703,115 women, April 2012–March 2017). The rate of uncomplicated or complicated composite pregnancy outcomes (hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes, preterm birth, neonate small- or large- for gestational age at birth, congenital anomaly, fetal death, antepartum bleeding or preterm prelabour membrane rupture) were calculated for women with and without obesity. Associations between uncomplicated pregnancy and maternal characteristics were explored in a population of women with obesity but without other pre-existing co-morbidities (e.g., essential hypertension) or obstetric risks identified in the first trimester (e.g., multiple pregnancy), using log binomial regression analysis.

Results

Of the studied Ontario maternity population (body mass index not missing) 17·7% (n = 117,236) were obese. Of these 20·6% had pre-existing co-morbidities or early obstetric complicating factors. Amongst women with obesity but without early complicating factors, 58·2% (n = 54,191) experienced pregnancy without complication; this is in comparison to 72·7% of women of healthy weight and no early complicating factors. Women with obesity and no early pregnancy complicating factors are more likely to have an uncomplicated pregnancy if they are multiparous, younger, more affluent, of White or Black ethnicity, of lower weight, with normal placental-associated plasma protein-A and/or spontaneously conceived pregnancies.

Conclusions

The study demonstrates that over half of women with obesity but no other pre-existing medical or early obstetric complicating factors, proceed through pregnancy without adverse obstetric complication. Care in lower-risk settings can be considered as their outcomes appear similar to those reported for low-risk nulliparous women. Further research and predictive tools are needed to inform stratification of women with obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, the prevalence of obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2) in women of reproductive age is rising, affecting approximately 31.8% of pregnant women in the United States of America, 21.3% in the United Kingdom (UK) and 19.0% in Canada [1,2,3]. Whilst it is well documented that women with obesity have at least a two-fold increase in prenatal complications (gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, thromboembolism) [4], it is unclear what proportion of women may have uncomplicated pregnancies, with previous studies either targeted at the absence of a previous complication, or reporting on uncomplicated pregnancy and birth together.

Two studies have been identified which report on prevalence of uncomplicated pregnancy for women with obesity. The UK Birthplace study (2014) reported that only 12.9% of women with obesity had a medical risk factor (e.g. asthma, diabetes) at the onset of pregnancy and by 37 weeks’ gestation, less than half (45.4%) had either a pre-existing or new obstetric risk factor (e.g. previous Caesarean section, pre-eclampsia) [5]. The authors reporting a secondary analysis of a prospective Dutch cohort study (2014) compared obstetric referral rates for pregnant women with obesity, to those for women of healthy weight. They reported no difference in the rate of obstetric referral between women of normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) and BMI 30–35 kg/m2. Of women with a BMI of 35 kg/m2 or above, 55% remained with midwifery-led care throughout pregnancy, and 30% had births in midwifery-led settings. Multiparity was associated with a greater chance of a midwifery-led pregnancy and birth across all BMI groups [6]. Vieira et al. (2017) studied the rate of uncomplicated pregnancy with uncomplicated birth, finding that 36.0% of women with obesity from their small cohort (n = 1409) had uncomplicated pregnancies and births. This outcome could be predicted using a combination of early pregnancy factors (multiparity, plasma adiponectin, glycated haemoglobin, maternal age and systolic blood pressure) with an AUROC of 0.72 (95% CI 0.68 to 0.76) [7].

The Ontario Public Health Association document on Informed Decision Making for Labour and Birth recognises that ‘In order to make an informed decision, individuals must receive the best scientific evidence of the benefits, risks and alternatives of an intervention from their [healthcare professional]’ [8]. Other settings, such as the UK, are also advocating for personalised care in maternity, where women are empowered to make informed choices [9]. A qualitative evidence synthesis which studied how women with obesity perceive prenatal and birth risks and make related choices identified that women’s relationships with their healthcare professionals and the nature of counselling received were influential in both [10]. Understanding the prevalence of uncomplicated pregnancy and its related factors, together with accurate prognostic information, is required to implement this vision of promoting evidence-based choices, both for pregnancy and for birth.

Methods

This study has been reported according to the guidelines issued in the STROBE statement (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology). This is available in Additional file 1.

Aim

The aim of this study was to calculate the rate of an uncomplicated pregnancy (antenatal period) in pregnant women with obesity and to determine the demographic and clinical factors which are associated with such uncomplicated pregnancies. We also set out to determine if the prediction of uncomplicated pregnancy using identified factors is feasible amongst women with obesity.

Study design

This population-based cohort study was conducted using routinely collected data stored within BORN (Better Outcomes Registry and Network) Ontario. BORN is a prescribed maternal, newborn and child registry funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. During the study period (April 2012 – March 2017), the data was entered from the pregnancies and births of 703,115 women.

Study population

Women with pregnancies ongoing beyond 22 + 0 gestational weeks, with complete data on weight and the exposures of interest (complete case analysis) were included. Women were included regardless of BMI, because a comparison was conducted between women of healthy and obese weights. Subgroups were formed through identification of early pregnancy complicating factors, defined as either pre-existing medical comorbidities or obstetric complicating factors present in the first trimester (Table 1). Otherwise healthy women are considered so because they do not have co-morbidities or early pregnancy complicating factors.

Exposures and outcomes

Pre-pregnancy BMI was calculated (kg/m2) using maternal pre-pregnancy weight and height. Weight was estimated from two sources: pre-pregnancy weight calculated by subtracting 2 kg from the first trimester weight recorded in the Perinatal Screening database in BORN Ontario, or self-reported pre-pregnancy weight recorded in the aggregated BORN Ontario dataset. Weight recorded in the Perinatal Screening database was prioritised because this was primarily measured rather than self-reported. The method of subtracting 2 kg to calculate pre-pregnancy weight from first trimester weight was established following modelling by Cheikh Ismail et al. (2016) [11]. Height was taken from that self-reported in the aggregated pregnancy dataset.

The primary outcome was the rate of uncomplicated pregnancy (antenatal period) in women with obesity. Uncomplicated pregnancy is a composite measure (Table 1) defined by the absence of both pre-existing medical co-morbidities (e.g., type 2 diabetes, essential hypertension), pre-existing/early obstetric (e.g., multiple pregnancy) or new-onset obstetric (e.g., gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia) complications. Uncomplicated labour and birth amongst the same group of women is outside the scope of this analysis, because its prediction is most suited to women in whom alternative low risk birthplace choices could most safely be offered, i.e., those women who have already had an uncomplicated pregnancy. It is therefore planned as a follow-up analysis.

We planned to compare the rate of uncomplicated pregnancy (absence of new onset pregnancy complications) (Table 1) between otherwise healthy women (no pre-existing medical or early obstetric complicating factors) with BMI above or below 30 kg/m2, and between women with a BMI in the obese range but with or without pre-existing medical or early obstetric complicating factors.

Finally, we planned to examine sociodemographic and clinical factors and determine whether they were associated with uncomplicated pregnancy in otherwise healthy women with obesity. The planned sociodemographic and clinical factors for study were based on a priori hypothesis and availability of data items: maternal age at conception, pre-pregnancy BMI (reported as continuous, not categorical), parity, race, first language (native/non-native), neighbourhood income quintiles, smoking or alcohol at first visit, timing of first trimester visit, women with adjusted placental-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) < 0.3 MoM, and use of assisted reproductive techniques. Those factors which were associated with the outcome on univariable analysis were taken forward for inclusion in the multivariable regression model.

Management of missing data

The level of missingness was calculated and reported for all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Height was missing in 10.4% of records and imputed for these cases using single imputation according to the median height for ethnicity. All analyses were conducted only in those women with a completed set of characteristics and outcomes, after imputation of missing height.

Statistical methods

The prevalence of pre-pregnancy obesity was calculated in categories of BMI as defined by the World Health Organization (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2: underweight, BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2: normal weight, BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2: overweight, BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m2: class I obesity, BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m2: class II obesity, and BMI ≥40.0 kg/m2: class III obesity) [12], and compared by reporting year.

The rate of uncomplicated pregnancy was calculated using frequency (n) and percentage (%) and compared among women with obesity and with or without early pregnancy complicating factors for antenatal complication using Chi-squared tests. The maternal socio-demographic characteristics and clinical factors of otherwise-healthy women with obesity were described (mean/standard deviation (SD) or n/% as appropriate) and compared between those with complicated and uncomplicated pregnancy (Chi-squared test, student t-test for parametric data and Kruskal-Wallis H test for non-parametric data). Log-transformation was applied to BMI data due to non-normal distribution.

Multivariable log-binomial regression models were used to estimate the adjusted relative risk (aRR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of the associations between uncomplicated pregnancy and associated sociodemographic or clinical factors, among women with obesity but no other early pregnancy complicating factors and compared to women without obesity or early pregnancy complicating factors. Potential confounders were identified by presence of a 10% change in the measure of association (crude/adjusted RR) for the exposure before and after introduction of confounders into the model. Where confounders were identified, these were used to adjust the final multivariable model.

Backward stepwise logistic regression was then used, with Akaike’s Information Criteria as the stop rule, to identify factors that were independently associated with uncomplicated pregnancy. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) was then used to calculate the accuracy of the multivariable model in discriminating between women with complicated and uncomplicated pregnancy.

All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) for Windows, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary.NC).

Results

Between 2012 and 2017, there were 703,115 pregnancies with data recorded in the BORN Ontario registry. Following exclusion of 42,455 women with missing weight (6.0%), the final study population was composed of 660,660 women. Of these, 17.7% (n = 117,236) had a recorded BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (Fig. 1). This is very similar to the rate of obesity reported for women aged 18–34 years, living in Ontario during 2016 (17.4%) [13]. The rate of obesity slowly increased year-on-year, from 17.4% in 2012/13 to 18.1% in 2016/17. Among women with obesity, 59.2% (n = 69,383) of women had class I obesity, 25.1% (n = 29,386) had class II obesity and 15.8% (n = 18,467) of women had class III obesity.

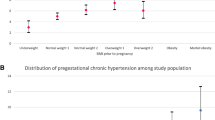

Of women with BMI ≥30 kg/m2, 20.6% of women had early pregnancy complicating factors (8.8% had medical risks, 13.5% had early obstetric complicating factors – some had both), compared to 16.5% of women with BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The reduction in the latter group was mostly in pre-existing medical complicating factors (8.8 to 5.0%; p < 0.001). The rates of pre-existing medical and early obstetric complicating factors for women within each BMI group are presented in Table 2.

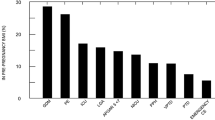

The rate of each complicating antenatal diagnosis from the ‘complicated pregnancy’ composite outcome is presented in Table 3 for the women without early pregnancy complicating factors, stratified by BMI group. For comparison, this table has also been reproduced for women with early pregnancy complicating factors in the Additional file 2. The rate of pregnancy-induced hypertension, gestational diabetes, intrauterine fetal death, large-for-gestational-age infant, and development of any pregnancy complication increases with advancing BMI category, both for women with and without early pregnancy complicating factors. The rate of preterm birth was highest for women with a low (< 18.5 kg/m2) or high (≥30 kg/m2) BMI (‘U’-shaped curve relationship). The rate of small-for-gestational-age/growth restricted infant and antepartum bleeding decreases with advancing BMI category but other complications have no clear trend.

Of 93,079 women with obesity but no early pregnancy complicating factors for antenatal complication, 54,191 (58.2%) had uncomplicated pregnancies. Of 24,157 women with obesity and other early pregnancy complicating factors, only 10,978 (45.4%) had uncomplicated pregnancies. The relative risk of complicated pregnancy for women with obesity and early pregnancy complicating factors, compared to otherwise healthy women who have obesity was 1.67 (95% CI: 1.63–1.72, p < 0.001).

Of women with obesity and no identified early pregnancy complicating factors, women with uncomplicated pregnancies were more likely to be younger, of a lower class of obesity, multiparous, Black or Caucasian ethnicity (than Asian or Other ethnicities), and in the highest two quintiles for neighbourhood income. They were less likely to have a low PAPP-A measurement, be of Asian ethnicity, and have conceived through assisted reproductive technology. On univariable analysis, first language (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.96–1.01, p = 0.28), smoking status (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.94–1.03, p = 0.87), alcohol consumption (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.98–1.06, p = 0.35), and timing of first trimester visit (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.92–1.02, p = 0.27) were not associated with the uncomplicated pregnancy outcome and therefore not included in the multivariable model. Frequency, percentage, crude and adjusted relative risks are presented in Table 4.

The characteristics predictive of uncomplicated pregnancy in women with obesity but no early pregnancy complicating factors were compared to those predictive for women of healthy weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) or overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m2) and without early pregnancy complicating factors for antenatal complication.

The predictive characteristics for women of healthy weight are summarised in Additional files 3 and 4. In women of healthy weight, PAPP-A < 0.3 MoM was more strongly associated with uncomplicated pregnancy outcome (aRR 0.76, 95% CI 0.73–0.79) compared to women with obesity (aRR 0.82, 95% CI 0.77–0.88). BMI category was confirmed as an effect modifier for the relationship with PAPP-A and uncomplicated pregnancy amongst women without early pregnancy co-morbidities or complications by post hoc Wald test (p < 0.0001).

Following stepwise logistic regression, maternal age, BMI, PAPP-A < 0.3 MoM, neighbourhood income quintiles 1 or 2, multiparity, ethnicity, and artificial reproductive techniques remained as independent predictors for the uncomplicated pregnancy outcome in women with obesity but no other early pregnancy complicating factors. The point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for the odds ratios are detailed in Table 5. Using the final prediction model, the AUROC for uncomplicated pregnancy was 0.578.

Discussion

This study aimed to calculate the rate of uncomplicated pregnancy among pregnant women with obesity and to determine the demographic and clinical factors which are associated with such uncomplicated pregnancies.

Through this large prospective cohort study of women with obesity in Ontario, Canada, we have identified that 79.4% of women with obesity had no other early pregnancy complicating factors (obstetric or co-morbidities). Of these, 58.2% had an uncomplicated pregnancy. Uncomplicated pregnancy was significantly more likely (RR: 1.28, 95% CI 1.26–1.30, p < 0.001) for women with obesity but no early pregnancy complicating factors compared to women with obesity and early pregnancy factors (45.4%). In women with obesity but without other early pregnancy complicating factors, an uncomplicated pregnancy was more likely if they were younger, with lower BMI, multiparous, black or Caucasian ethnicity or in the highest three quintiles for neighbourhood income; and less likely if the women had a low PAPP-A measurement at prenatal screening, were of Asian ethnicity or had conceived through artificial reproductive techniques. At present, these predictive factors identified through population-level routinely collected data were not strong enough to discriminate between uncomplicated and complicated pregnancy outcomes in this group.

Comparison with existing literature

The prevalence of uncomplicated pregnancy in this study is very similar to the rates reported in the UK Birthplace cohort, where less than half (45.4%) of women with obesity had either a pre-existing or new obstetric risk factor (e.g., previous Caesarean section, pre-eclampsia) at the time of admission to the maternity unit for birth [5], and the Dutch cohort study (2014), where 55% of women with BMI > 35 kg/m2 did not require referral for obstetric care during pregnancy [6].

Where our study differs from these national cohort studies is in the comparison of complications for women with obesity with and without pre-existing complicating factors, and in the study of characteristics associated with an uncomplicated pregnancy outcome. As in Vieira et al’s proof of concept study (2017) uncomplicated pregnancy was independently associated with multiparity and younger age [7]. Many of the predictors in Vieira’s study are not routinely collected, limiting immediate translational potential. We also identified additional predictors in BMI (continuously reported), ethnicity, markers of socioeconomic deprivation, use of fertility treatments and PAPP-A; this information is routinely available for the majority of women giving birth in moderate- or high-income settings.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study are in the large cohort used from a country with universal access to healthcare, providing an opportunity to identify risk of even rare outcomes, e.g., intrauterine fetal death, and in the methodology to stratify women with obesity according to presence or absence of early pregnancy complications which will inform pathways of prenatal of care. It is important to note the methodological limitations of using a routinely collected dataset, including our choice of using self-reported pre-pregnancy weight where measured weight was not available and the decision to impute height using single imputation for mean height in the ethnic group for the 10.4% of women for whom height was not recorded. It has previously been established that heavier women are more likely to underestimate their weight when self-reporting [14, 15], however self-reported and measured values for BMI are highly correlated [16,17,18]. Whilst our assumptions may have led to a small proportion of women being placed into the incorrect BMI category, given the large sample size, uncertainty in the presented estimates is expected to be minimal. Finally, we did not have access to data on clinical and biochemical measurements (e.g., systolic blood pressure or parameters of glucose metabolism) which have previously been shown to improve prediction of uncomplicated outcomes in this population [7].

Implications for practice and policy

In some settings it is routine practice to manage otherwise low-risk nulliparous women in midwifery-led or primary care settings where available, if they choose to do so. The rate of complicated outcomes in the group of women with obesity appears to be similar, it therefore follows that these women with obesity should also have the option of having prenatal care in midwifery-led settings, assuming that appropriate surveillance and timely reflex referral to higher-risk care providers continues for potential complications (e.g., routine screening for gestational diabetes and blood pressure/urine tests for signs of pre-eclampsia).

Further research

Confidence in risk stratification strategies for this group of women is expected to improve with the aid of decision support tools, incorporating predictive algorithms. The predictive power demonstrated in this study was limited by the absence of clinical, ultrasound and biochemical measurements. Other cohort studies have recognised that these additional factors, not present in routinely-collected registries, augment predictive power [19, 20]. Furthermore, the different performance of biochemical markers for prediction of adverse outcome in pregnant women with obesity has previously also been shown [7, 21]. Further research is required to develop, test and validate a predictive tool, specific to pregnant women with obesity, which incorporates these additional parameters, and to conduct a similar analysis which separately identifies the rate and factors associated with uncomplicated birth amongst women with obesity but otherwise uncomplicated prenatal periods.

Conclusions

The study demonstrates that over half of women with obesity, but no other pre-existing medical or early obstetric complicating factors proceed through pregnancy without adverse obstetric complication. This is similar to the rate of uncomplicated pregnancy noted in nulliparous women through an international cohort study [22]. Whilst the ability to predict uncomplicated outcomes needs further research, acknowledgement and prediction has the potential to personalise the provision of care to women with obesity, including provision of care in low risk settings for women most likely to have uncomplicated pregnancies, and triaging women at high risk of complications into care settings which are set up to monitor for and offer treatment for these.

Availability of data and materials

The data analysed during this study is held securely at the prescribed registry BORN Ontario. Data sharing regulations prevent this data from being made available publicly due to the personal health information in the datasets. Enquiries regarding BORN data must be directed to BORN Ontario (Science@BORNOntario.ca).

Abbreviations

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver operating curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BORN:

-

Better Outcomes Registry and Network

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- IUGR:

-

Intrauterine growth restriction

- LGA:

-

Large for gestational age

- MoM:

-

Multiples of median

- PAPP-A:

-

Placenta associated plasma protein A

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SGA:

-

Small for gestational age

- STROBE:

-

STrengthening Reporting OBservational studies in Epidemiology

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

2014–2014 biennial report - facts from Ontario [http://www.bornontario.ca/en/about-born/governance/annual-reports/2014-2016-annual-report/facts-from-ontario/] Accessed 29 Sept 2020.

Poston L, Caleyachetty R, Cnattingius S, Corvalan C, Uauy R, Herring S, Gillman MW. Preconceptional and maternal obesity: epidemiology and health consequences. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(12):1025–36.

National maternity and perinatal audit: clinical report 2019. Based on births in NHS maternity services between 1 April 2016 and 31 March 2017. [https://maternityaudit.org.uk/pages/reports] Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

Denison FC, Aedla NR, Keag O, Hor K, Reynolds RM, Milne A, Diamond A, Royal College of O, Gynaecologists. Care of women with obesity in pregnancy: green-top guideline no. 72. BJOG. 2019;126(3):e62–e106.

Hollowell J, Pillas D, Rowe R, Linsell L, Knight M, Brocklehurst P. The impact of maternal obesity on intrapartum outcomes in otherwise low risk women: secondary analysis of the birthplace national prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121(3):343–55.

Deemers D, Wijnen H, van Limbeek E, Bude L, Nieuwenhuijze M, Spaanderman M, de Vries R. The impact of obesity on outcomes of midwife-led pregnancy and childbirth in a primary care population: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2014;121:1403–14.

Vieira MC, White SL, Patel N, Seed PT, Briley AL, Sandall J, Welsh P, Sattar N, Nelson SM, Lawlor DA, et al. Prediction of uncomplicated pregnancies in obese women: a prospective multicentre study. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):194.

Informed decision-making for labour & birth [https://opha.on.ca/Position-Papers/Informed-Decision-Making-for-Labour-and-Birth-v-2.aspx] Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

Better Births: Improving outcomes of maternity services in England. [https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/national-maternity-review-report.pdf? PDFPATHWAY=PDF] Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

Relph S, Ong M, Vieira MC, Pasupathy D, Sandall J. Perceptions of risk and influences of choice in pregnant women with obesity. An evidence synthesis of qualitative research. PLoS One. 2020;15(1):e0227325.

Cheikh Ismail L, Bishop DC, Pang R, Ohuma EO, Kac G, Abrams B, Rasmussen K, Barros FC, Hirst JE, Lambert A, et al. Gestational weight gain standards based on women enrolled in the fetal growth longitudinal study of the INTERGROWTH-21st project: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2016;352:i555.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report on a WHO Consultation on Obesity, Geneva, 3–5 June, 1997 [https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63854] Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

Statistics Canada. Health characteristics, annual estimates [https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009601]. Accessed 29 Sept 2020.

Robinson E. Overweight but unseen: a review of the underestimation of weight status and a visual normalization theory. Obes Rev. 2017;18(10):1200–9.

Dzakpasu S, Duggan J, Fahey J, Kirby RS. Estimating bias in derived body mass index in the Maternity experiences survey. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36(9):185–93.

Natamba BK, Sanchez SE, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Concordance between self-reported pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and BMI measured at the first prenatal study contact. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):187.

Bannon AL, Waring ME, Leung K, Masiero JV, Stone JM, Scannell EC, Moore Simas TA. Comparison of self-reported and measured pre-pregnancy weight: implications for gestational weight gain counseling. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21(7):1469–78.

Holland E, Moore Simas TA, Doyle Curiale DK, Liao X, Waring ME. Self-reported pre-pregnancy weight versus weight measured at first prenatal visit: effects on categorization of pre-pregnancy body mass index. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17(10):1872–8.

Sovio U, Smith G. Evaluation of a simple risk score to predict preterm pre-eclampsia using maternal characteristics: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2019;126(8):963–70.

Kenny LC, Black MA, Poston L, Taylor R, Myers JE, Baker PN, McCowan LM, Simpson NA, Dekker GA, Roberts CT, et al. Early pregnancy prediction of preeclampsia in nulliparous women, combining clinical risk and biomarkers: the screening for pregnancy endpoints (SCOPE) international cohort study. Hypertension. 2014;64(3):644–52.

Vieira MC, Poston L, Fyfe E, Gillett A, Kenny LC, Roberts CT, Baker PN, Myers JE, Walker JJ, McCowan LM, et al. Clinical and biochemical factors associated with preeclampsia in women with obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(2):460–7.

Chappell LC, Seed PT, Myers J, Taylor RS, Kenny LC, Dekker GA, Walker JJ, McCowan LM, North RA, Poston L. Exploration and confirmation of factors associated with uncomplicated pregnancy in nulliparous women: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347(f6398):f6398.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was supported in part by personal grants to SR (Guy’s and St Thomas’ charity, UK), MCV (BEX 9571/13–2; CAPES, Brazil; http://www.capes.gov.br) and DP (Tommy’s Charity, UK) and by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) MFM-146444 and FDN-148438. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, writing the report or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR developed the research question and methodology, refined the analysis, interpreted the results, and wrote the final manuscript. YG developed the methodology and conducted the statistical analysis. AH developed the methodology and contributed to analysis. MCV developed the research question and statistical analysis plan. DC developed the methodology and contributed to the analysis. LG developed the methodology, interpreted the data from a Canadian perspective and supervised the Canadian team. DP conceived the idea, developed the methodology and interpreted the results. All authors contributed and agreed to the final draft manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used anonymised BORN Ontario birth registry data which is regulated by Ontario’s Personal Health Information Protection Act, 2004 (PHIPA). As a registry, BORN is afforded the authority to collect, use and disclose personal health information, without consent, for the purpose of facilitating or improving the provision of health care. This special authority requires BORN to develop and adhere to privacy policies that have been reviewed and approved by the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. Research Ethics Board (REB) approvals were obtained from the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Research Ethics Board (18/23PE) and the Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (20180855-01H).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

STROBE checklist

Additional file 2: Appendix Table 1

. Rate of specific antenatal complications in women with early pregnancy complicating factors, stratified by BMI group

Additional file 3: Appendix Table 2

. Characteristics associated with uncomplicated pregnancy in women of healthy weight (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) but no other early pregnancy complicating factors

Additional file 4: Appendix Table 3

. Characteristics associated with uncomplicated pregnancy in women who are overweight (BMI 25.0–29.9 kg/m) but no other early pregnancy complicating factors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Relph, S., Guo, Y., Harvey, A.L.J. et al. Characteristics associated with uncomplicated pregnancies in women with obesity: a population-based cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 182 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03663-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03663-2