Abstract

Background

Maternal mental health including postpartum mental health is essential to women’s health. This study aimed to develop a specific measure for assessing postpartum depression literacy and consequently evaluate its psychometric properties among a sample of perinatal women.

Methods

This investigation was composed of two studies: developing the measure, and evaluating of psychometric properties of the developed questionnaire. In development stage an item pool was created. Then, based on definition of mental health literacy and preliminary screening, an initial questionnaire was developed. The content and face validity of the questionnaire were then assessed. In the second study psychometric properties of the questionnaire were examined. Overall 692 perinatal women with the mean age of 27.63 years (ranging from 17 to 43) participated in the study.

Results

In all an item pool of 86 items was generated. Of these, 31 items were removed and the remaining 55 items subjected to content and face validity and further 16 items removed. In the second stage a 39-item questionnaire namely the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale (PoDLis) was evaluated. In principal component factor analysis, 31 items were loaded indicating a 7-factor solution for the questionnaire. The factors designated the following constructs: ability to recognize postpartum depression, knowledge of risk factors and causes, knowledge and belief of self-care activities, knowledge about professional help available, beliefs about professional help available, attitudes which facilitate recognition of postpartum depression and appropriate help-seeking, and knowledge of how to seek information related to postpartum depression. Finally performing the confirmatory factor analysis, the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale with 31 items was supported for the structures suggested by theoretical model and findings from the exploratory factor analysis. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the scale was .78 and it ranged from .70 to .83 for each factor lending support to the internal consistency of the questionnaire.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale (PoDLiS) is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring the postpartum depression literacy and now can be used in studies of mental health literacy in women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Postpartum depression is a common problem among women [1, 2]. Postpartum depression can negatively impact the health and well-being of the mother and babies. Untreated postpartum depression can extend the probability of chronic mental health and suicidal behaviors. Furthermore, the insecure attachments are more likely to be developed between infants and depressed mothers. Also it has been reported that infants of such as mothers may have more developmental and behavioral problems [3].

Only about 40% of women with depression are identified by health care providers and a significant percentage of women do not obtain treatment for their depressive symptoms [4]. Also, usually most women do not proactively seek professional help for signs and symptoms of depression during the postpartum period, even if treatment is offered and accessible [5,6,7]. The lack of knowledge about signs and symptoms of depression and treatment possibilities, have been considered as a major help-seeking barrier during the postpartum period [5, 6], indicating how significant is the role of women’s depression literacy in the help-seeking process [8]. Thus providing the knowledge and skills are essential for women to recognize postpartum depression and obtain efficient treatment [9]. Postpartum depression literacy may be conceived as a particular type of mental health literacy, defined as the knowledge and beliefs about mental health disorders that aid their recognition, management or prevention [8].

Mental health literacy consists of the following attributes: (a) the ability to recognize mental health disorders, (b) knowledge and beliefs about risk factors and causes, (c) knowledge and beliefs regarding self-help strategies, (d) knowledge and beliefs of professional help and treatment options, (e) attitudes which promote recognition and appropriate help-seeking, and (f) knowledge of how to seek mental health information [10].

However, currently no instrument exists for measuring postpartum depression literacy within mental health literacy framework. To the best of our knowledge, there are only two studies that measured postpartum depression literacy but none of them used a specific measure: Thorsteinsson et al. in their study, applied three vignettes that met the diagnostic requirements for major depressive episode as per the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) [11]. Fonceca et al. in a study used the Portuguese version of the depression literacy questionnaire [12] which consisted of 22 true/false/do not know items. Each correct answer was scored 1, and the total score ranged from 0 to 22 points. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the questionnaire (to assess internal consistency) was .77 [13].

However, as one might consider there is a gap in the literature and therefore, we tried to overcome this shortcoming by developing an instrument for measuring postpartum depression literacy in women in order to facilitate future studies on the topic with a broader application. In particular, the present study aimed to develop a specific scale of mental health literacy for postpartum depression and then provide an evaluation of its psychometric properties. We anticipated that this new scale might be used both as a screening measure of literacy and as a measure for assessing the impact of interventions on the promotion of mental health literacy among women.

Methods

Study 1: Developing the measure

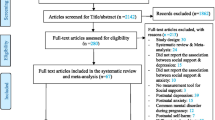

Study 1 included four stages of item generation, content validity, face validity and providing provisional version of the questionnaire.

Item generation

A review of all measures of mental health literacy and qualitative studies was carried out in order to generate an item pool. As such a number of items were adapted from other measures [11, 12, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Then, based on the Jorm’s definition of mental health literacy [8], an initial questionnaire was developed. The initial questionnaire contained 86 items. After a careful review of the items by the research team, the number of items was reduced to 55. Operational definitions of the six attributes of mental health literacy and decisions regarding item generation are presented in the Table 1.

Content validity

Both qualitative and quantitative content analysis was performed. For qualitative content validity 15 experts in health education and promotion, reproductive health and psychology were requested to assess the questionnaire for grammar, wording, item allocation, and scaling. After collecting experts’ opinions, essential changes were considered in the questionnaire and 11 items were removed. For quantitative content validity, in order to calculate the Content Validity Ratio (CVR), the same experts were asked to assess each item on a 3-point Likert scale (where 1 = essential, 2 = useful but unessential, and 3 = unessential). Then, based on Lawshe’s table [28], the values greater than or equal to 0.49 were kept in the scale. In this stage, five items were removed. In order to calculate the Content Validity Index (CVI), the experts were asked to determine the relevance, clarity and simplicity of items using a 4-point Likert scale. A CVI score of 0.79 or above indicates good content validity [29]. The CVI score for all questions was calculated and found to be satisfactory (ranging from 0.80 to 1). Content validity ratio; and content validity index were made simultaneously.

Face validity

Similar to previous stage both qualitative and quantitative methods were used. The qualitative face validity was carried out by using open-ended questions. As such 15 perinatal women were recruited using convenience sampling to determine the ambiguity, relevance and difficulty of each item. At this stage, none of the items were deleted. At the quantitative stage, the impact score of each item was calculated. For this purpose, another sample of 40 perinatal women was requested to identify the importance of each item on a 5-point Likert scale including very important, important, relatively important, slightly important, and unimportant. Then impact score was calculated. For calculation of item impact score, first the percentage of women who scored 4 to 5 for each item (frequency) was indicated, and then item impact score of instrument items was calculated by following formula: Item impact score = frequency (%) × importance. The items with impact scores of 1.5 or above was considered acceptable [30, 31]. The impact score for items ranged from 1.8 to 3.8.

Provisional version of the questionnaire

Following the content and face validity, the provisional version of the questionnaire with 39 items was provided and subjected to psychometric evaluation. The questionnaire was named the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale (PoDLiS). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree or not likely at all and 5 = strongly agree or very likely, reverse items score oppositely). Scores for each subscale and the whole questionnaire determined by summing items dividing into the number of items for each subscale and for the whole questionnaire giving a score of 1 to 5 either for each subscale or the whole questionnaire.

Study 2: Psychometric properties of the postpartum depression literacy scale

Design and participants

A cross-sectional study was conducted on a convenient sample of pregnant and postnatal women attending to the prenatal and pediatric clinics of a teaching hospital affiliated to Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Eligibility criteria to take part in the study were as follows: being 18 years or older, being currently pregnant or having given birth during the previous 12 months, and having ability to read and write properly (had to have completed primary education). As suggested we estimated that a sample of 400 perinatal women would be enough for this study (10 individuals per item of the questionnaire) [32]. However, in practice 447 women participated in the study and completed the PoDLiS. In addition since we performed confirmatory factory analysis a different sample (n = 245) was recruited. In fact overall 692 perinatal women participated in the study.

Statistical analysis

Construct validity and reliability were performed to assess psychometric properties of the questionnaire. To investigate the construct validity, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were used. To assess reliability, internal consistency analysis was performed. These are described as follows.

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA)

The principal component analysis was conducted on 39 items using oblique rotation. The oblique methods allow the factors to correlate if we believe that the factors (latent concepts) are correlated [33]. To determine the number of potential underlying factors, eigenvalues above 1, a minimum factor loading of 0.4, a maximum of 25 rotation iterations and a scree plot were used [34, 35]. Also the rotation of factor analysis converged at six iterations. To assess the appropriateness of the sample for the factor analysis, The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were applied [35, 36].

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

The confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test whether the data fit theoretical model. The CFA analysis carried out according to the Jorm’s model (6 attributes) and the findings from the exploratory factor analysis using covariance indexes and the maximum-likelihood estimation method. The goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed using relative chi-square (χ2/df), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) [37]. For goodness-of-fit indexes, the following values thought acceptable: were χ2/df ≤ 2, GFI, CFI, and NFI > .95, RMSEA < .06, and SRMR < .08 [38, 39].

Reliability

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to assess internal consistency of the whole scale and each factor separately.

Results

The sample characteristics

The mean age of respondents was 27.63 (SD = 5.46) years and it was 12.99 (SD = 2.46) years for their formal education. Almost 90% of the participants were housewife and 42.1% of respondents said that psychologists were their first source of seeking help if they would suffer from postpartum depression. The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 2.

Exploratory factor structure

After confirming the adequacy of the sampling based on the KMO and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (KMO = .783) and χ2 (741, n = 447) = 4449, P < .001 (two-tailed), 11 factors emerged with eigenvalues of greater than 1, which accounted for 60.63% of the variance observed. By using the scree plot [40] and according to the dimensions of mental health literacy, the number of factors was limited to 7 with loading 31 items and an explanation for 49% of the total variance. These seven factors are presented as follows: ability to recognize postpartum depression (6 items), knowledge of risk factors and causes (5 items), knowledge and belief of self-care activities (5 items), knowledge about professional help available (2 items), beliefs about professional help available (2 items), attitudes that facilitate recognition of postpartum depression and appropriate help-seeking (6 items) and knowledge of how to seek information related to postpartum depression (5 items). The results are shown in Table 3.

Confirmatory factor structure

The CFA was performed on six attributes of mental health literacy according to the Jorm’s model to check the theoretical model fit. The results showed a good fit to the data. The goodness fit indexes for the proposed model were: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .040, normal fit index (NFI) = .764, comparative fit index (CFI) = .919, incremental fit index (IFI) = .921, goodness-of-fit index (GFI) = .871, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .074 (Table 4). The results of the confirmatory factor analysis are shown in Fig. 1. However, as shown in Table 4 we performed the CAF analysis for the seven attributes of the instrument derived from the exploratory factor analysis and found that this model also revealed a good fit to the data with a very small better goodness of fit indexes (Fig. 2).

Reliability

The Cornbrash’s alpha coefficient for the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale was .78 and for ability to recognize postpartum depression was .77 and for risk factors and causes, knowledge and beliefs of self-care activities, knowledge about professional help available, beliefs about professional help available, attitudes which facilitate recognition of postpartum depression and appropriate help-seeking and knowledge of how to seek information related to postpartum depression were .76, 78, .83, .78, .70, .73, respectively. The results are shown in Table 5.

Postpartum depression literacy score

The mean postpartum depression literacy for the study sample was found to be 3.79 (SD =0.39) and it was 3.68 (SD = 0.75) for ability to recognize postpartum depression, 3.69 (SD = 0.77), 4.50 (SD = 0.56), 4.10 (SD = 0.91), 2.53 (SD = 1.08), 3.77 (SD = 0.78) and 3.71 (SD = 0.77) were for knowledge of risk factors and causes, knowledge and beliefs of self-care activities, knowledge about professional help available, beliefs about professional help available, attitudes which facilitate recognition of postpartum depression and appropriate help-seeking, knowledge of how to seek information related to postpartum depression respectively.

The relationship between postpartum depression literacy and socio-demographic and clinical characteristics

There were statistically significant differences in the postpartum depression literacy score by age, education, occupation and source of seeking information about postpartum depression. Univariate analyses showed that older age, higher education and being employed and student were associated with higher postpartum depression literacy. Also, respondents who said book, the Internet, psychologists, psychiatrics, radio and television were their first source of seeking information had higher postpartum depression literacy (Table 6).

Discussion

This study was the first attempt to design and psychometrically evaluate an instrument to measure postpartum depression literacy among women. The initial questionnaire was developed based on review of all measures of mental health literacy, qualitative studies and definition of mental health literacy and its frameworks [41]. After the completion of the validity and reliability phases, the Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale (PoDLiS) consisted of 31 items tapping into 7 factors that now can be used to evaluate knowledge of signs and symptoms of postpartum depression and attitudes toward mental health and help-seeking. One of the features of the PoDLiS is that, in addition to assessment of each component of the mental health literacy as relates to postpartum depression, existence of scoring system included a coalition of all attributes of mental health literacy and provided a theoretically meaningful structure for the scale. As most participants completed the questionnaire without any problems in about 15 min, we believe that the PoDLiS is an easy-to-use questionnaire and can be utilized in future studies.

The current study used both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses to assess the structure of the PoDLiS with almost 692 perinatal women and the EFA revealed seven attributes factorial structure for the scale. This however was a slightly different from the framework that indicated by Jorm. However, the confirmatory factor analysis revealed a satisfactory fit between the data and both six attributes of the original Jorm’s model and the seven attributes that we extracted from the exploratory factor analysis. The Jorm’s framework contains six attributes (the ability to recognize mental health disorders, knowledge and beliefs about risk factors and causes, knowledge and beliefs regarding self-help strategies, knowledge and beliefs of professional help and treatment options, attitudes which promote recognition and appropriate help-seeking and knowledge of how to seek mental health information) while as mentioned earlier in EFA analysis we found seven factors for the PoDLiS. In fact knowledge and beliefs about professional help available in our study was divided into two constructs: knowledge about professional help seeking and beliefs about professional help seeking.

According to the results, 42.1% of respondents said that psychologists were their first source of seeking help if they would suffer from postpartum depression following by friends and family members in second place. Also, 27.2% of respondents said that the Internet was their first source of seeking information following by psychologists in second place. The results of an Australian study found that general physicians were the primary source of seeking help and information for the presented vignette [11].

The findings revealed that the mean score of more attributes of postpartum depression literacy such as ability to recognize postpartum depression, knowledge of risk factors and causes, attitudes which promote recognition of postpartum depression and appropriate help-seeking and knowledge of how to seek information related to postpartum depression were these all in the moderate range. Thus, the need to improve knowledge about postpartum depression symptoms, risk factors, causes and treatment by educational interventions among women during the perinatal period seems essential. Also, specific strategies should be developed in order to overcome postpartum depression stigma.

Most women stated that the Internet was the first source of seeking information about postpartum depression. Indeed conducting interventions to assess the effects of credible online information on women’s postpartum depression literacy might be helpful.

Furthermore, our results showed that the highest and lowest mean scores of different dimensions were knowledge and beliefs on self-care activities and beliefs about professional help available respectively. Health professionals should provide women with education during pregnancy about self-care activities such as physical activity that may lessen distress during the postpartum period [42]. Teaching about the use of antidepressants as a treatment option should be a priority for health professionals.

Participants in our study had good knowledge of mental health professionals and the services they provide. It may be helpful to provide information about professional help and treatment options, as it will help women make right decisions about their mental health.

We showed that overall women presented moderate level of postpartum depression literacy during the perinatal period, which was consistent with the results of Fonceca et al. [13]. This finding showed that women at perinatal period did not have adequate knowledge about postpartum depression, suggesting the need for exploring and developing facilitators such as postpartum depression literacy that affecting women’s help-seeking behaviors. Education should be provided through community campaigns, as well as by presenting mental health in childbirth classes during pregnancy [43, 44].

Finally, we explored the relationship between sociodemographic and clinical variables and the postpartum depression literacy. Differences were found regarding age, education, occupation and source of information about postpartum depression. Fonceca et al. showed that among sociodemographic variables, education and income levels correlated with the depression literacy and based on clinical variables, there was not any correlation between perinatal period and parity with the depression literacy [13]. These results were in line with those seen in our study.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, this was a hospital-based study. Thus the sample might not be a representative of perinatal population. Future studies might benefit from including a community sample of women. Secondly, intention to develop a brief and easily administered measure may have resulted in insufficient assessment of its attributes. However, multiple sources were used to achieve consensus in guiding item development and testing, including use of the literature, the research team (experts) and a broad testing process. Finally, we did not perform convergent and discriminant validity and test-retest reliability. The future studies should include more psychometric analysis, such as convergent and discriminant validity and test-retest reliability.

Implications and future research

Use of The Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale will enable efficient identification of high risk women who may benefit from further education or support. This scale may also allow the detection of changes within an individual or population in order to assess the impact of programs to improve postpartum depression literacy and prevent or manage postpartum depression.

In addition future studies should be carried out in different environments and cultures. Perhaps the evaluation of such studies may lead to a stronger confirmation of the psychometric properties of the PoDLiS. However, responsiveness of the scale (sensitivity to change) will be assessed by researchers following this study.

Conclusion

The Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale provided a valid measure to assess all attributes of mental health literacy related to postpartum depression and an understanding of knowledge and beliefs about postpartum depression among perinatal women. This understanding is necessary to improving mental health status of women. It has good psychometric properties and easily administered. The Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale (PoDLiS) can be used in assessing level of postpartum depression literacy in pregnant women or new mothers and in determining the impact of programs designed to improve mental health literacy related to postpartum depression.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to restriction by Tarbiat Modares University but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CFA:

-

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- CVI:

-

Content validity Index

- CVR:

-

Content validity Ratio

- DSM-V:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- GFI:

-

Goodness-of-fit index

- IFI:

-

Incremental fit index

- KMO:

-

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

- NFI:

-

Normal fit index

- PoDLiS:

-

Postpartum Depression Literacy Scale

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean square residual

References

Horowitz JA, Murphy CA, Gregory KE, Wojcik J. A community-based screening initiative to identify mothers at risk for postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(1):52–61.

O'hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression—a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

Field T. Infants of depressed mothers. Infant Behavior & Development 1995;18(1):1–13.

Ko JY, Farr SL, Dietz PM, Robbins CL. Depression and treatment among US pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, 2005–2009. J Womens Health. 2012;21(8):830–6.

Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment preferences: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323–31.

Fonseca A, Gorayeb R, Canavarro MC. Women′ s help-seeking behaviours for depressive symptoms during the perinatal period: socio-demographic and clinical correlates and perceived barriers to seeking professional help. Midwifery. 2015;31(12):1177–85.

O'Mahen HA, Flynn HA. Preferences and perceived barriers to treatment for depression during the perinatal period. J Womens Health. 2008;17(8):1301–9.

Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166(4):182–6.

Letourneau NL, Dennis C-L, Benzies K, Duffett-Leger L, Stewart M, Tryphonopoulos PD, et al. Postpartum depression is a family affair: addressing the impact on mothers, fathers, and children. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012;33(7):445–57.

Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(5):396–401.

Thorsteinsson EB, Loi NM, Moulynox AL. Mental health literacy of depression and postnatal depression: a community sample. Open J Depres. 2014;3(03):101.

Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF, Evans K, Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(4):342–9.

Fonseca A, Silva S, Canavarro MC. Depression literacy and awareness of psychopathological symptoms during the perinatal period. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46(2):197–208.

Campos L, Dias P, Palha F, Duarte A, Veiga E. Development and psychometric properties of a new questionnaire for assessing mental health literacy in young people. Universitas Psychologica. 2016;15(2):61–72.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Link BG, Kikuzawa S, Burgos G, Swindle R, et al. Americans’ views of mental health and illness at century’s end: continuity and change. Bloomington: Indiana Consortium for Mental Health Services Research; 2000.

Ugarriza DN. Postpartum depressed women's explanation of depression. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(3):227–33.

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95.

Guy S, Sterling BS, Walker LO, Harrison TC. Mental health literacy and postpartum depression: a qualitative description of views of lower income women. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28(4):256–62.

Abrams LS, Dornig K, Curran L. Barriers to service use for postpartum depression symptoms among low-income ethnic minority mothers in the United States. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(4):535–51.

Nicole L, Duffett-Leger L, Stewart M, Hegadoren K, Dennis CL, Rinaldi CM, et al. Canadian mothers’ perceived support needs during postpartum depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2007;36(5):441–9.

Fischer EH, Turner JI. Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1970;35(1p1):79.

Evans-Lacko S, Little K, Meltzer H, Rose D, Rhydderch D, Henderson C, et al. Development and psychometric properties of the mental health knowledge schedule. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(7):440–8.

Angermeyer MC, Däumer R, Matschinger H. Benefits and risks of psychotropic medication in the eyes of the general public: results of a survey in the Federal Republic of Germany. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1993;26(04):114–20.

O’Connor M, Casey L. The mental health literacy scale (MHLS): a new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(1–2):511–6.

Mcluckie A, Kutcher S, Wei Y, Weaver C. Sustained improvements in students’ mental health literacy with use of a mental health curriculum in Canadian schools. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):379.

Ghanbari S, Ramezankhani A, Montazeri A, Mehrabi Y. Health literacy measure for adolescents (HELMA): development and psychometric properties. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0149202.

Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity 1. Pers Psychol. 1975;28(4):563–75.

Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29(5):489–97.

Bilandi RR, Farahamni FK, Ahmadi F, Kazemnejad A, Mohamadi R, Amiri M. Psychometric properties of the iranian version of modified RHAQWRA questionnaire. J Family Reprod Health. 2015;9(4):184.

Lacasse Y, Godbout C, Series F. Health-related quality of life in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):499–503.

Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research: lippincott Williams & wilkins; 2005.

Leech NL, Barrett KC, Morgan GA. IBM SPSS for intermediate statistics: use and interpretation: Routledge; 2014.

Osborne JW, Costello AB, Kellow JT. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis. In: Best Practices in Quantitative Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2008. p. 86-99.

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. The theory of measurement error. Psychom Theory. 1994;3:209–47.

Harrington D. Confirmatory factor analysis: Oxford university press. USA; 2008.

Bollen KA, Noble MD. Structural equation models and the quantification of behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(Supplement 3):15639–46.

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, Ullman JB. Using multivariate statistics. Boston: Pearson; 2007.

Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55.

Cattell RB. The scree test for the number of factors. Multivar Behav Res. 1966;1(2):245–76.

Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: empowering the community to take action for better mental health. Am Psychol. 2012;67(3):231.

Da Costa D, Lowensteyn I, Abrahamowicz M, Ionescu-Ittu R, Dritsa M, Rippen N, et al. A randomized clinical trial of exercise to alleviate postpartum depressed mood. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2009;30(3):191–200.

Callister LC, Beckstrand RL, Corbett C. Postpartum depression and help-seeking behaviors in immigrant Hispanic women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(4):440–9.

Mnich E, Makowski AC, Lambert M, Angermeyer MC, von dem Knesebeck O. Beliefs about depression—do affliction and treatment experience matter? Results of a population survey from Germany. J Affect Disord. 2014;164:28–32.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the doctoral thesis of the first author (FM) in health education and promotion. The authors appreciate all of the perinatal women who participated in this research project.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FM was the main investigator, designed the study, collected the data and drafted the manuscript. FG was the study supervisor and contributed to study design, analysis and writing process. AN was the study advisor and contributed to the questionnaire development and the writing process. AM was the study advisor, contributed to the designs and methodology and critically reviewed the manuscript and provided the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of the Tarbiat Modares University approved the study. (approval no: IR.TMU.REC.1394.265). In addition to this, we obtained permission from the hospital authorities. Participants were informed of the goals of the study and we also obtained written informed consent from all participants. Participants were made certain that their name and information would be kept confidential and they were told that they were free to not complete the questionnaire if they did not desire to do so.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mirsalimi, F., Ghofranipour, F., Noroozi, A. et al. The postpartum depression literacy scale (PoDLiS): development and psychometric properties. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 20, 13 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2705-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2705-9