Abstract

Background and objectives

The perinatal period presents a high-risk time for development of mood disorders. Australia-wide universal perinatal care, including depression screening, make this stage amenable to population-level preventative approaches. In a large cohort of women receiving public perinatal care in Sydney, Australia, we examined: (1) the psychosocial and obstetric determinants of women who signal distress on EPDS screening (scoring 10–12) compared with women with probable depression (scoring 13 or more on EPDS screening); and (2) the predictive ability of identifying women experiencing distress during pregnancy in classifying women at higher risk of probable postnatal depression.

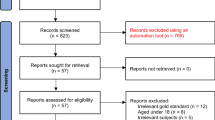

Methods

We analysed routinely collected perinatal data from all live-births within public health facilities from two health districts in Sydney, Australia (N = 53,032). Perinatal distress was measured using the EPDS (scores of 10–12) and probable perinatal depression was measured using the EPDS (scores of 13 or more). Logistic regression models that adjusted for confounding variables were used to investigate a range of psychosocial and obstetric determinants and perinatal distress and depression.

Results

Eight percent of this cohort experienced antenatal distress and about 5 % experienced postnatal distress. Approximately 6 % experienced probable antenatal depression and 3 % experienced probable postnatal depression. Being from a culturally and linguistically diverse background (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.8–2.3, P < 0.001), a lack of partner support (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI 2.3–3.7) and a maternal history of childhood abuse (AOR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.6–2.3) were associated with antenatal distress. These associations were similar in women with probable antenatal depression. Women who scored 10 to12 on antenatal EPDS assessment had a 4.5 times higher odds (95% CI 3.4–5.9, P < 0.001) of experiencing probable postnatal depression compared with women scoring 9 or less.

Conclusion

Antenatal distress is more common than antenatal depressive symptoms and postnatal distress or depression. Antenatal maternal distress was associated with probable postnatal depression. Scale properties of the EPDS allows risk-stratification of women in the antenatal period, and earlier intervention with preventively focused programs. Prevention of postnatal depression could address a growing burden of illness and long-term complications for mothers and their infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anxiety and depression are the most common complications of the perinatal period, affecting approximately 10–15% of women [1,2,3], with a global trajectory of increasing burden [4]. This pooled estimate varies widely between and within countries [5]. When undetected these disorders pose a range of risks to the mother’s health, psychosocial wellbeing, relationships and her infant’s development [6]. In Australia, death by suicide or trauma remain the two leading causes of death in the first postpartum year [7], with the great majority of cases having had psychiatric diagnoses including substance use identified [8]. An increasing body of literature suggests perinatal depression and anxiety interrupt the mother-infant relationship leading to a range of neurocognitive, psychiatric and developmental problems in the offspring of affected mothers [9,10,11,12]. Maternal distress has also been shown to contribute to the amplification of parenting stress, birth complications such as premature labour [13] and low birth weight [14], and lead to adverse consequences for child growth and development [15].

Local and international research has confirmed that antenatal depression is more prevalent than postnatal depression peaking in its burden in the third trimester [16,17,18], suggesting a proportion of women with postnatal depression are experiencing a continuation of symptoms from the antenatal period. The reported prevalence of antenatal and postnatal depression in Australia is 6–17% and 3–11% respectively [17, 19], increasing markedly in culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities. Antenatal depression has been found to be associated with low self-esteem, low levels of social support, negative cognitive style, recent major life events, low income and a maternal history of abuse [20]. Postnatal depression is most strongly predicted by presence of antenatal depression [2, 17, 19,20,21], and goes on to be the major predictor of parenting stress [20]. While there is now sufficient evidence to reliably identify antenatal depression as a major risk factor for postnatal depression, an area that has been poorly investigated is whether antenatal distress is a risk factor for postnatal depression, and whether there are similarities in the socio-demographic and obstetric determinants of women with perinatal distress compared with perinatal depression. The degree to which co-morbid anxiety contributes to perinatal mood disorder has gained more appropriate attention recently [22]. Distress that is sub-threshold for a diagnosis of major depression may cause significant functional disability as it is more commonly associated with anxiety symptoms [23]. The concept of maternal distress has been described in detail elsewhere [24].

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is a self-reported screening questionnaire initially designed for use in the postnatal period [25]. As the tool became more widely available, it demonstrated its utility as a cross-culturally valid tool for use in multiple settings. The Australian National Perinatal Depression Initiative [26] endorsed the use of the EPDS as part of a universally-delivered psychosocial assessment for women receiving maternity care in the public health care system. In these settings, a score of 13 or more merits possible referral for specialised assessment or at least re-application of the EPDS within two to 3 weeks [27]. Validation studies of the EPDS in the antenatal period have justified higher cut-offs due to concern that transient heightened distress in pregnancy will be captured and misclassified [28]. However, heightened anxiety during pregnancy has been linked with poor perinatal outcomes [13, 29, 30] and contributes significantly to the symptom burden [31].

The present study aims to investigate the biopsychosocial and obstetric determinants of antenatal and postnatal distress (defined as EPDS 10 to 12) and probable depression (EPDS 13 or more) in a large and culturally-diverse cohort in Australia. We examine the capacity of an antenatal EPDS score of 10 to 12 predicting development of postnatal depression, defined as an EPDS score of 13 or more.

Methods

Data source

This study was based on a retrospective cohort of mothers of all live births (N = 53,032) in public health facilities in South Western Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD) and the Sydney Local Health District (SLHD) in 2014 to 2016, in New South Wales (NSW), Australia. Antenatal data routinely collected by midwives were linked to postnatal data routinely collected by child and family health nurses, using unique individual identifiers that allowed linkage of maternal and child health data from the various services (e.g., antenatal, hospital, postnatal, child and family) attended. The unique individual identifier is a code that does not include personal identification information about either the mother and/or the infant. Antenatal information (such as sociodemographic characteristics, alcohol use, partner support, antenatal health problems, maternal history of childhood abuse, and history of intimate partner violence) were collected by qualified midwives in the first antenatal visit. Similarly, the mode of delivery data was recorded immediately post-birth, while postnatal information (e.g., postnatal depression using the EPDS) was collected by qualified child and family health nurses. These data are stored in the Information Management & Technology Division (IM&TD) database in each health district. After ethics approvals were obtained, the data were cleaned and coded for analysis.

Study setting

SWSLHD and SLHD represents approximately 52% of the Sydney metropolitan population, with over 1,621,000 residents. This region of Sydney is one of Australia’s most culturally diverse, with approximately half of all mothers born overseas [32, 33]. Mothers from the Middle East & Africa (11%), South East Asia (10%), Southern Asian (8%) and North East Asia (7%) are most commonly represented [34]. SWSLHD and SLHD are socioeconomically diverse, with contrasting extreme disadvantage and advantage present across the Sydney metropolitan area [35].

Risk factors

Study variables include: maternal age (categorised as less than 20, 20 to 34, or over 35 years); area-based socioeconomic status (SES, low, medium or high); CALD (yes or no); partner support (yes or no); maternal history of childhood abuse (yes or no); history of psychological IPV (yes or no); history of physical intimate partner violence (IPV, yes or no); pregnancy known to community services (yes or no); previous child in out-of-home care (OOHC, yes or no); alcohol use in pregnancy (yes or no); history of antenatal health problems (such as gestational diabetes or hypertension, yes or no); and type of delivery (normal vaginal, assisted vaginal or caesarean delivery).

Area-based SES was measured using the Socio-Economic Index for Areas (SEIFA), and based on the mother’s address. SEIFA is a composite indicator developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics that ranks areas in Australia according to relative socioeconomic advantage and disadvantage [36]. Deciles of SES were categorised into high (top 10% of the population), medium (middle 80% of the population) and low (bottom 10% of the population), consistent with previous publications [35, 37]. CALD is a term used for communities with diverse characteristics including but not limited to: language, ethnicity, nationality, dress, traditions, food, social structures, art and religion [38]. Data relating to IPV was collected based on the NSW Domestic Violence – Identifying and Responding policy [39], where women are asked: “Within the last 12 months, have you been hit, slapped or hurt in other ways by your partner or ex-partner (physical IPV)?” or “Are you frightened of your partner or ex-partner (psychological IPV)?”

Outcome variables

The main outcome variables in the present study are antenatal depressive symptoms or distress, and postnatal depressive symptoms or distress, measured using the EPDS. During routine antenatal care, midwives collect psychosocial information including maternal depressive symptoms at the first visit. Non-English speaking pregnant women and mothers may use translated versions of the EPDS where available, which are produced by the New South Wales Multicultural Health Communication Service [40]. Alternatively, women completed the English version of the EPDS through accredited interpreters. Numerous validation studies, using the English version of the EPDS, have demonstrated that a score of 13 or more strikes the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity in classifying English-speaking women who are experiencing a major depressive episode postnatally [25, 41, 42]. Though this cut-off correctly detects clinical caseness, lower scores of 10–12 are likely to demonstrate the presence of distress, the consequences of which are poorly researched and understood. Research suggests that the EPDS multi-dimensionally measures anxiety [43, 44], dysphoria and depression [45]. The final score is calculated by combining overall scores to achieve a total score out of 30, then coded as a categorical variable (score of less than 10, score of 10 to 12, score of 13 and above), with a score of 10 to 12 indicating distress and a score of 13 or more suggestive of antenatal depressive symptoms [25].

Data on postnatal depressive symptoms were collected within the first 6 weeks of birth. The total number of postnatal depressive symptoms was also combined to obtain a total score (out of 30) and coded as a categorical variable (score of less than 10, score of 10 to 12, score of 13 and above). We disaggregated the antenatal and postnatal score (to include 10 to 12) to examine the associations for women who are distressed, but who are not currently offered structured clinical assessment, as the cut-off for assessment remains 13 or more. In the present analysis, EPDS cut-points used to indicate probable depression were selected based on previously published studies [35, 46,47,48] and the current Australian endorsed guidelines on improving mental health outcomes for parents and infants [49].

The EPDS is the most commonmly used and widely-accepted screening tool for identifying depressive symptoms in the perinatal period worldwide, with a reported sensitivity of 68–86% and specificity of 78–96% [25, 42]. An Australian validation study of 4148 women, reported a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 89% [41]. An EPDS score of 13 or more has been demonstrated to have a positive predictive value (PPV) for detecting major depression of 70% in the Australian setting [41]. The EPDS has been validated across a range of cultures [41, 42, 50,51,52,53] and has demonstrated its superiority to unstructured health professional assessment or routine care both internationally and in Australia [54,55,56]. The EPDS has been translated into a number of languages, including a validation study conducted in South Western Sydney in Vietnamese and Arabic-speaking women [57]. Women from over 25 countries are represented in this study cohort [37].

Statistical analysis

The initial analysis involved the calculation of frequencies and prevalence of perinatal distress and depressive symptoms by study factors. Univariate regression models were used to investigate the association between study factors and the outcome measures of perinatal distress and depressive symptoms, followed by multivariate regression models that adjusted for confounders. Predictors of antenatal and postnatal distress or depressive symptoms were investigated in logistic regression models to determine if there was an association with key study factors. The confounding factors considered in the present study were based on previously published reports [20, 58, 59] include alcohol consumption during pregnancy, smoking during pregnancy, sex of the infant, maternal body mass index and birthing facility. A similar analytical strategy was used to account for the potential confounding relationship between study factors and perinatal distress or depressive symptoms. Odds ratios, and their corresponding confidence intervals, were estimated and reported as the measure of association between study factors and outcome variables.

Missing data

The study also investigated the potential effect of missing data on estimated odds ratios in sensitivity analyses, which were conducted on an imputed data set based on the original cohort comprising complete study factors and outcome data. Multivariate imputation by chained equation was used in the analysis [60], which assumes that data are missing at random and that the characteristics of known participants can be used to estimate the characteristics of participants with missing data [61]. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the ice command in Stata (Stata Corp, V.15.0, College Station, TX, USA), based on 25 multiple imputations [62]. We estimated and reported the revised odds ratios and the corresponding confidence intervals from the imputed dataset, using the mim command.

Results

Antenatal distress (EPDS 10–12)

The prevalence of antenatal distress was 8.0% in this cohort. This figure was higher in mothers who reported physical intimate partner violence (IPV) (14.1%) and lack of partner support (15.3%). Being from a CALD background (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI 1.79–2.26, P < 0.001), maternal experience of childhood abuse (AOR = 1.9, 95% CI 1.61–2.32, P < 0.001), having a previous child in out-of-home care (AOR = 1.5, 95% CI 1.19–1.93, P < 0.001), having an unsupportive partner (AOR = 2.9, 95% CI 2.30–3.67, P < 0.001), reporting alcohol use in pregnancy (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI 1.11–2.32, P = 0.011), experience of antenatal medical problems (AOR = 1.2, 95% CI 1.08–1.43, P = 0.002) and report of physical IPV (AOR = 1.6, 95% CI 1.10–2.33, P = 0.013) were associated with experiencing antenatal distress (defined as EPDS 10–12) compared with women who did not report these factors to be present. Maternal age of < 20 years (AOR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.01–2.85, P = 0.045) was associated with antenatal distress compared with women aged between 21 and 34. Pregnant women from higher, compared with lower, socio-economic backgrounds were less likely to experience antenatal distress (AOR = 0.7, 95% CI 0.61–0.91, P = 0.004). In this cohort, antenatal distress was not associated with maternal age ≥ 40, “medium” socioeconomic status, report of psychological IPV or if a previous pregnancy was known to child protective services (see Table 1 for figures).

In this cohort, an antenatal EPDS score of 10 to 12 was significantly associated with higher odds of having either persistent distress during postnatal follow-up (EPDS 10–12, AOR = 4.3, 95% CI 3.51–5.22, P < 0.001) or development of probable postnatal depression (EPDS≥13, AOR = 4.5, 95% CI 3.4–5.9, P < 0.001).

Antenatal depressive symptoms (or high depressive symptoms, EPDS ≥13)

The prevalence of antenatal depressive symptoms was 5.9% in this cohort, but much higher if there was reported presence of psychological or physical IPV (25.0% or 20.3%, respectively) or experience of an unsupportive partner (28.3%). As with antenatal distress, antenatal depressive symptoms were associated with being from a CALD background, maternal experience of child abuse and report of psychological or physical IPV (see Table 2 for figures). Compared with mothers from low socioeconomic backgrounds, women from medium or high socioeconomic backgrounds were less likely to experience antenatal depressive symptoms. Antenatal depressive symptoms were not associated with maternal age group, previous child being known to child protective services or in an out-of-home care placement, alcohol use or medical problems in pregnancy.

For women with probable antenatal depression (EPDS≥13), the odds of persistence into the postnatal period was significantly raised (AOR = 13.0, 95% CI 10.32–16.47, P < 0.001).

Postnatal distress (EPDS 10–12)

The prevalence of postnatal distress was 5.3% in this cohort. Postnatal distress was associated with being from a CALD background (AOR = 1.3, 95% CI 1.13–1.56, P = 0.001), a reported maternal history of child abuse (AOR = 1.4, 1.07–1.80, P = 0.013), and having had an assisted vaginal birth, as compared with non-assisted vaginal delivery (AOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.26–2.08, P < 0.001). Having a previous child in out-of-home care decreased the likelihood of developing postnatal distress (AOR = 0.6, 95% CI 0.37–0.97, P = 0.039), as did being from a higher socioeconomic background (AOR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.07–1.78). Postnatal distress was not associated with maternal age group, having had the pregnancy known to child protective services, lack of partner support, alcohol use or medical problems during pregnancy and finally, reported psychological or physical IPV (see Table 3 for figures).

Postnatal depressive symptoms (or high depressive symptoms, EPDS ≥13)

The prevalence of postnatal depressive symptoms was 3.1% in this cohort, but much higher if there was reported presence of psychological IPV (10%). As with postnatal distress, postnatal depressive symptoms were associated with being from a CALD background, maternal experience of child abuse, report of psychological or physical IPV and having an assisted vaginal delivery (see Table 4 for figures). Additionally, postnatal depressive symptoms were significantly associated with having had the pregnancy known to child protective services, lack of partner support and having had a Caesarean birth.

Sensitivity analysis of the revised odds ratios and corresponding confidence intervals were not significantly different from the complete imputed case analysis, indicating that missing data did not substantially affect the observed findings.

Discussion

The prevalence of antenatal distress in this cohort was estimated at 8.0% and shares higher odds of coming from a CALD or low SES background, a maternal history of experiencing child abuse and lack of partner support, with probable antenatal depression (prevalence of 5.9%). The prevalence of postnatal distress is estimated at 5.3% and shares risk factors with women whose scores indicate probable postnatal depression (prevalence of 3.1%), including being from a CALD background, a maternal history of experiencing child abuse and having had an assisted vaginal delivery.

In this cohort, pregnant women experiencing distress during their pregnancy have four times higher odds of experiencing ongoing distress postnatally or deteriorating further and developing probable postnatal depression, compared with women who scored 9 or less on EDPS screening during their pregnancy. To our knowledge, this is the first time a longitudinal quantitative association has been reported. Currently women signalling distress (EPDS score 10–12) may be offered reassessment within 2 to 4 weeks [49]. If this reassessment reveals ongoing distress with a sub-threshold score, specific interventions are not necessarily offered. If reapplication demonstrates score creep to 13 or more, mental health assessment is usually offered. A criticism of this approach is that the response becomes manualised and crisis driven and is more likely to require intensive, costly treatment and cause potentially preventable suffering. This data supports treating women who score 10 to 12 more proactively and viewing these scores as existing on a continuum where increasing symptomatology produces a higher score, rather than presence of illness being viewed in a binary format, as the current scoring system reflects, and therefore how the data collected were chosen to be analysed.

In 2008, the Australian Government provided $85 million to fund the National Perinatal Depression Initiative [26]. These funds were allocated to state and territory governments with the purpose of delivering universal screening in the antenatal and postnatal period and respond to women who were either experiencing depression or at risk of developing depression. Beyondblue, an independent non-profit mental health organisation, was tasked with supporting implementation of this initiative. At the conclusion of this 5 year roll-out, beyondblue identified national analytics and integration with support services as areas of program development that were not yet systematic in their delivery [63]. In recent years, New South Wales Health has adopted an integrated care strategy with the primary objective of delivering cohesive care to targeted patient groups [64]. Underpinned by a proportionate universalism and health equity philosophy, this approach scales and intensifies intervention in response to identified need [65]. This strategy could inform an integrated response to risks identified during routine psychosocial assessment and exploit the stratification characteristics of the EPDS.

This study has a number of policy implications. The work corroborates previous research in identifying a range of risk factors for antenatal and postnatal depressive symptoms [17, 20, 66]. It adds to the growing body of literature suggesting that specific attention should be paid to women who are distressed though not necessarily clinically depressed during pregnancy, demonstrating a number of shared risk factors with women who develop probable depression [22, 67]. Using the properties of the EPDS in this way emphasises managing symptoms and function, and shifts focus away from only intervening when there is a definable psychiatric diagnosis. Current practice may dismiss pregnant women’s distress as it is considered ‘expected’ or because it is predominantly characterised by anxiety. A novel finding of this study is the demonstration that antenatal EPDS scores can be used to predict the likelihood of postnatal psychological distress or depressive symptoms. We have shown that women scoring 10 to 12 on the EPDS, who are likely to be distressed, are currently underserved by policy recommendations for repeat testing, rather than offering intervention with a preventative focus.

Policy recommendations for appropriate intervention could draw from the breadth of experimental-control trials that have applied non-pharmacological interventions with the aim of preventing postpartum depression. Evidence of efficacy is varied, though interventions exert greater effect if a risk stratification procedure is applied as a condition of eligibility [68]. These interventions include psychological debriefing post birth [69,70,71,72,73], interpersonal, couples-based and cognitive-behavioural therapies [74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82], antenatal and postnatal classes [83,84,85,86,87,88,89], professional or lay-based home visiting [90,91,92,93,94], lay-based telephone support [95], continuity of care and carer [96,97,98], early and flexible postpartum care [99], web- and computer-based programs [100,101,102,103], and mindfulness-based therapies [104].

Study limitations and strengths

Limitations in study design have been considered by the authors. Firstly, a source of recall and measurement bias is introduced by the self-report nature of a range of questions asked of women during antenatal and postnatal psychosocial assessment. This bias may be introduced in either direction, causing over- or underestimation of the association between risk factor and depressive symptoms. Secondly, this analysis relies on routinely collected and human-scored service data which may present a range of limitations including inaccurate input, coding errors, meaningfully different missing data and an inability to establish temporal correlation between variables and antenatal depressive symptoms collected contemporaneously. The dataset is linked to postnatal data however, which means a temporal relationship between variables and postnatal depression can be established. Thirdly, there are a number of important study factors, such as level of social support outside an intimate partner relationship, past history of psychiatric illness, type of antenatal health problem and markers of pregnancy and parenting preparedness that are not reflected in this dataset and may represent important mediating relations. Fourth, this dataset does not provide an indication of whether women experiencing distress or depression are presenting with these symptoms for the first time, which has implications for risk stratification and management. Fifth, distress is a generic term that fails to capture a range of contributory causes such as trauma or stressor-related conditions. Sixth, we acknowledge that women with long-standing mental illness may not score highly on EPDS screening, either because of the chronicity of their illness or concern regarding the consequences of a high-score. Seventh, the lack of a specific assessment for the outcome variables among women from various cultural backgrounds is another limitation of the study given the varied EPDS cut-offs used in examining probable perinatal depression in these populations. Specific evidence pertaining to women from CALD communities signalling antenatal or postnatal distress and/or depressive symptoms may be helpful in targeted advocacy and policy interventions. We recognise that in current service delivery the cut-off score derived from English-speaking population studies is applied to all women, regardless of whether the EPDS was completed in its translated form. Furthermore, it is not well understood to what extent translated versions of the EPDS, or translators, are used in these settings. Lastly, this dataset covers the majority of women across the two health districts, but misses those who have their antenatal and delivery care privately. This could introduce a degree of reporting bias as the distribution of maternal age, socioeconomic status and other risk factors may be different between cohorts.

Despite these limitations, there are a range of study strengths. Firstly, we take advantage of routinely collected data that reflects a diverse cohort of women and can be used to inform contextually appropriate policy and practice. As Australian healthcare systems have moved to electronic medical records, the Australian Government released principles of data integration, calling for the strategic use of available resources to drive research and policy justification [105]. Three advantages to the approach taken for this study include (1) the cost-effectiveness of analysing routinely collected data and ensuring a return on public investment; (2) the use of real-world data to evaluate the impact of delivered policy; and (3) the use of internally linked data to provide a longitudinal picture and allow causal inference.

Another study strength is the application of multiple imputations to decrease the potential for bias secondary to missing data. Odds ratios were calculated with the complete dataset and again with the imputed dataset assuming the data were missing at random. Sensitivity analysis reveals that results were unlikely to be affected by missing data.

The EPDS, as with any screening tool, has had a range of criticisms levelled against aspects of its delivery, use and interpretation, reviewed recently by Matthey and Agostini [106]. We are aware that many women who are experiencing a major depressive episode may not, and should not, be identified by EPDS screening alone and conversely women who score highly may not be experiencing a major depressive episode. We are also aware that there is conjecture in the literature as to whether the EPDS has uni- or multidimensional psychometric properties and the use of a range of cut-off scores in validation studies across a range of cultures and pregnancy time-points [107]. Notwithstanding these criticisms, its wide and routine use in Australia makes it a central tool for research and evidence-informed policy. Furthermore, while the EPDS scores would be viewed as a continuum result, current Australian policy recommendations around perinatal depression screening do not support the continuum approach.

Conclusion

Women scoring 10 to 12 on the EPDS during both antenatal and postnatal assessment share a similar burden of risk factors when compared with women scoring 13 or more. These include coming from a CALD background, maternal experience of childhood abuse and presence of psychological or physical IPV. Women experiencing distress (scoring 10 to 12) on antenatal assessment are at high risk for persisting distress or developing postnatal depressive symptoms (scoring 13 or more postnatally). This study suggests that while screening for mood disorder in pregnancy is appropriate and necessary, a singular cut-off of 13 or more for further assessment is not supported by this analysis. Risk stratification and integration of population-level preventative interventions is one such instrument that should be further explored.

Availability of data and materials

Only listed member on the ethics approval are able to access the data used for this analysis. Any data requests or queries need to be forwarded to: South Western Sydney Local Health District Ethics Committee (Research and Ethics Office, Locked Bag 7103, Liverpool BC, NSW, 1871; Phone: + 61 (02) 87388304; Fax: + 61 (02) 87388310; E: research.support@sswahs.nsw.gov.au; and Sydney Local Health District Ethics committee c/− Research Ethics and Governance Office (REGO), Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Missenden Road CAMPERDOWN, NSW, 2050; Phone: + 61 (02) 95156766; Facsimile: + 61 (02) 95157176.

Abbreviations

- CALD:

-

Culturally and linguistically diverse

- EPDS:

-

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- FaCS:

-

Family and Community Services

- IPV:

-

Intimate partner violence

- NSW:

-

New South Wales

- OOHC:

-

Out-of-home-care

- SES:

-

Socio-economic status

- SLHD:

-

Sydney Local Health District

- SWSLHD:

-

South Western Sydney Local Health District

References

Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–95.

O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression-a meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8(1):37–54.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e442.

Binti Mohd Arifin SR, Cheyne H, Maxwell M. Review of the prevalence of postnatal depression across cultures. AIMS Public Health. 2018;5(3):260–95.

Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis C-L, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1775–88.

Thornton C, Schmied V, Dennis C-L, Barnett B, Dahlen HG. Maternal deaths in NSW (2000–2006) from nonmedical causes (suicide and trauma) in the first year following birth. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:623743.

Austin M-P, Kildea SV, Sullivan ED. Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Med J Aust. 2007;186(7):364–7.

National Research Council and Institute of Medicine Committee on Depression, Parenting Practices the Healthy Development of children. Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. England MJ and Sim LJ, Eds. Washington: National Academies Press (US); 2009.

Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ. The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 2):53–61.

Weissman MM, Wickramaratne P, Gameroff MJ, Warner V, Pilowsky D, Kohad RG, et al. Offspring of depressed parents: 30 years later. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(10):1024–32.

Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(1):1–27.

Hedegaard M, Henriksen TB, Sabroe S, Secher NJ. Psychological distress in pregnancy and preterm delivery. Br Med J. 1993;307(6898):234–9.

Lou H, Nordentoft M, Jensen F, Pryds O, Nim J, Hemmingsen R. Psychosocial stress and severe prematurity. Lancet. 1992;340(8810):54.

Hollins K. Consequences of antenatal mental health problems for child health and development. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19(6):568–72.

ALSPAC Study Team. ALSPAC–the Avon longitudinal study of parents and children. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15(1):74–87.

Ogbo FA, Eastwood J, Hendry A, Jalaludin B, Agho KE, Barnett B, et al. Determinants of antenatal depression and postnatal depression in Australia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):49.

Gaynes BN, Gavin N, Meltzer-Brody S, Lohr KN, Swinson T, Gartlehner G, et al. Perinatal depression: Prevalence, screening accuracy, and screening outcomes: Summary. In: AHRQ Evidence Report Summaries Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 1998–2005; 2005. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11838/.

Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Bilszta JL, Hayes B, Barnett B, Brooks J, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: a large prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1–2):147–57.

Leigh B, Milgrom J. Risk factors for antenatal depression, postnatal depression and parenting stress. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:24.

Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–85.

Austin MP. Antenatal screening and early intervention for “perinatal” distress, depression and anxiety: where to from here? Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2004;7(1):1.

Preisig M, Merikangas K, Angst J. Clinical significance and comorbidity of subthreshold depression and anxiety in the community. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;104(2):96–103.

Khanlari S, Barnett B, Ogbo FA, Eastwood J. Re-examination of perinatal mental health policy frameworks for women signalling distress on the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) completed during their antenatal booking-in consultation: a call for population health intervention. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):221.

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6.

Australian Government Department of Health. National Perinatal Depression Initiative Canberra 2008. Updated 18 April 2013; Cited 2018 31 October. Available from: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/mental-perinat.

NSW Department of Health. NSW Health/Families NSW. Supporting Families Early Package - SAFE START Guidelines: Improving mental health outcomes for parents and infants. North Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2009.

Matthey S, Henshaw C, Elliott S, Barnett B. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale – implications for clinical and research practice. Arch Women’s Ment Health. 2006;9(6):309–15.

Glover V, O'Connor TG. Effects of antenatal stress and anxiety: implications for development and psychiatry. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:389.

Austin MP, Leader L. Maternal stress and obstetric and infant outcomes: epidemiological findings and neuroendocrine mechanisms. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;40(3):331–7.

Reading AE. The influence of maternal anxiety on the course and outcome of pregnancy: a review. Health Psychol. 1983;2(2):187.

South Western Sydney Local Health District. Research Strategy for South Western Sydney Local Health District 2012–2021. Sydney: South Western Sydney Local Health District; 2012.

NSW Government: Health. Sydney Local Health District Planning: Local District Profiles 2018. Updated 11 October 2018; Cited 2018 3 November. Available from: https://www.slhd.nsw.gov.au/planning/profiles.html.

Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. New South Wales Mothers and Babies 2016. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017.

Eastwood J, Ogbo FA, Hendry A, Noble J, Page A, Early Years Research Group. The impact of antenatal depression on perinatal outcomes in Australian women. Plos One. 2017;12(1):e0169907.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Technical paper: socio-economic indexes for areas (SEIFA) 2011. Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra; 2013.

Ogbo FA, Eastwood J, Page A, Arora A, McKenzie A, Jalaludin B, et al. Prevalence and determinants of cessation of exclusive breastfeeding in the early postnatal period in Sydney, Australia. Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12(1):16.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. Culturally and linguistically diversity (CALD) characteristics 2016. Available from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4529.0.00.003~2014~Main%20Features~Cultural%20and%20Linguistic%20Diversity%20(CALD)%20Characteristics~13.

NSW Department of Health. Policy and procedures for identifying and responding to domestic violence. North Sydney: NSW Department of Health; 2006.

NSW Government. Multicultural Health Communication Service NSW Governmnet; 2018. Available from: http://www.mhcs.health.nsw.gov.au/publicationsandresources#c3=eng&b_start=0&c4=edinburgh.

Boyce P, Stubbs J, Todd A. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale: validation for an Australian sample. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1993;27(3):472–6.

Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:288–90.

Grigoriadis S, de Camps MD, Barrons E, Bradley L, Eady A, Fishell A, et al. Mood and anxiety disorders in a sample of Canadian perinatal women referred for psychiatric care. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 2011;14(4):325–33.

Tran TD, Tran T, La B, Lee D, Rosenthal D, Fisher J. Screening for perinatal common mental disorders in women in the north of Vietnam: a comparison of three psychometric instruments. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1):281–93.

Kwan R, Bautista D, Choo R, Shirong C, Chee C, Saw SM, et al. The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale as a measure for antenatal dysphoria. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2015;33(1):28–41.

Eastwood JG, Phung H, Barnett B. Postnatal depression and socio-demographic risk: factors associated with Edinburgh depression scale scores in a metropolitan area of New South Wales, Australia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(12):1040–6.

Fox CR, Gelfand DM. Maternal depressed mood and stress as related to vigilance, self-efficacy and mother-child interactions. Early Dev Parenting. 1994;3(4):233–43.

Kohlhoff J, Hickinbotham R, Knox C, Roach V, Barnett AB. Antenatal psychosocial assessment and depression screening in a private hospital. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;56(2):173–8.

Austin MP, Highet N. And the expert working group. Mental health care in the perinatal period: Australian clinical practice guideline. Centre of Perinatal Excellence: Melbourne; 2017.

Rubertsson C, Börjesson K, Berglund A, Josefsson A, Sydsjö G. The Swedish validation of Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) during pregnancy. Nord J Psychiatry. 2011;65(6):414–8.

Felice E, Saliba J, Grech V, Cox J. Validation of the Maltese version of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2006;9(2):75–80.

Adouard F, Glangeaud-Freudenthal NM, Golse B. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in a sample of women with high-risk pregnancies in France. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):89–95.

Gibson J, McKenzie-McHarg K, Shakespeare J, Price J, Gray R. A systematic review of studies validating the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale in antepartum and postpartum women. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119(5):350–64.

Barnett B, Lockhart K, Bernard D, Manicavasagar V, Dudley M. Mood disorders among mothers of infants admitted to a mothercraft hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 1993;29(4):270–5.

Hearn G, Iliff A, Jones I, Kirby A, Ormiston P, Parr P, et al. Postnatal depression in the community. Br J Gen Pract. 1998;48(428):1064–6.

Schaper A, Rooney B, Kay N, Silva P. Use of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale to identify postpartum depression in a clinical setting. J Reprod Med. 1994;39(8):620–4.

Barnett B, Matthey S, Gyaneshwar R. Screening for postnatal depression in women of non-English speaking background. Arch Women’s Mental Health. 1999;2(2):67–74.

Brown S, Lumley J. Physical health problems after childbirth and maternal depression at six to seven months postpartum. BJOG. 2000;107(10):1194–201.

Banti S, Mauri M, Oppo A, Borri C, Rambelli C, Ramacciotti D, et al. From the third month of pregnancy to 1 year postpartum. Prevalence, incidence, recurrence, and new onset of depression. Results from the perinatal depression-research & screening unit study. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52(4):343–51.

Van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL. Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):681–94.

Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393.

Spratt M, Carpenter J, Sterne JA, Carlin JB, Heron J, Henderson J, et al. Strategies for multiple imputation in longitudinal studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(4):478–87.

Highet NJ, CA P. The National Perinatal Depression Initiative: A synopsis of progress to date and recommendations for beyond 2013. Melbourne: Beyondblue, the national depression and anxiety initiative; 2012.

New South Wales Ministry of Health. NSW Integrated Care Strategy: NSW Government: Health 2016. Updated 25 July 2016; Cited 2018 10 October. Available from: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/integratedcare/Pages/integrated-care-strategy.aspx.

Amelung, VE. et al., Eds. Handbook integrated care. Switzerland: Springer; 2017.

O'Hara MW. Social support, life events, and depression during pregnancy and the puerperium. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(6):569–73.

Furber CM, Garrod D, Maloney E, Lovell K, McGowan L. A qualitative study of mild to moderate psychological distress during pregnancy. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(5):669–77.

Dennis C-L. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for prevention of postnatal depression: systematic review. BMJ. 2005;331(7507):15.

Gamble J, Creedy D, Moyle W, Webster J, McAllister M, Dickson P. Effectiveness of a counseling intervention after a traumatic childbirth: a randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2005;32(1):11–9.

Lavender T, Walkinshaw SA. Can midwives reduce postpartum psychological morbidity? A randomized trial. Birth. 1998;25(4):215–9.

Priest SR, Henderson J, Evans SF, Hagan R. Stress debriefing after childbirth: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2003;178(11):542–5.

Small R, Lumley J, Toomey L. Midwife-led debriefing after operative birth: four to six year follow-up of a randomised trial. BMC Med. 2006;4:3.

Tam WH, Lee DT, Chiu HF, Ma KC, Lee A, Chung TK. A randomised controlled trial of educational counselling on the management of women who have suffered suboptimal outcomes in pregnancy. BJOG. 2003;110(9):853–9.

Zlotnick C, Johnson SL, Miller IW, Pearlstein T, Howard M. Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(4):638–40.

Zlotnick C, Miller IW, Pearlstein T, Howard M, Sweeney P. A preventive intervention for pregnant women on public assistance at risk for postpartum depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8):1443–5.

Le HN, Perry DF, Stuart EA. Randomized controlled trial of a preventive intervention for perinatal depression in high-risk Latinas. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79(2):135–41.

Gao LL, Chan SW, Li X, Chen S, Hao Y. Evaluation of an interpersonal-psychotherapy-oriented childbirth education programme for Chinese first-time childbearing women: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(10):1208–16.

Weidner K, Bittner A, Junge-Hoffmeister J, Zimmermann K, Siedentopf F, Richter J, et al. A psychosomatic intervention in pregnant in-patient women with prenatal somatic risks. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;31(3):188–98.

Fisher JR, Wynter KH, Rowe HJ. Innovative psycho-educational program to prevent common postpartum mental disorders in primiparous women: a before and after controlled study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1):432.

Chabrol H, Teissedre F, Saint-Jean M, Teisseyre N, Roge B, Mullet E. Prevention and treatment of post-partum depression: a controlled randomized study on women at risk. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):1039–47.

Austin MP, Frilingos M, Lumley J, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Roncolato W, Acland S, et al. Brief antenatal cognitive behaviour therapy group intervention for the prevention of postnatal depression and anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2008;105(1–3):35–44.

Matthey S, Kavanagh DJ, Howie P, Barnett B, Charles M. Prevention of postnatal distress or depression: an evaluation of an intervention at preparation for parenthood classes. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1):113–26.

Brugha TS, Wheatley S, Taub NA, Culverwell A, Friedman T, Kirwan P, et al. Pragmatic randomized trial of antenatal intervention to prevent post-natal depression by reducing psychosocial risk factors. Psychol Med. 2000;30(6):1273–81.

Feinberg ME, Kan ML. Establishing family foundations: intervention effects on coparenting, parent/infant well-being, and parent-child relations. J Fam Psychol. 2008;22(2):253.

Gjerdingen DK, Center B. A randomized controlled trial testing the impact of a support/work-planning intervention on first-time parents’ health, partner relationship, and work responsibilities. Behav Med. 2002;28(3):84–91.

Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, Magriples U, Massey Z, Reynolds H, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):330–9.

Reid M, Glazener C, Murray GD, Taylor GS. A two-centred pragmatic randomised controlled trial of two interventions of postnatal support. BJOG. 2002;109(10):1164–70.

Stamp GE, Williams AS, Crowther CA. Evaluation of antenatal and postnatal support to overcome postnatal depression: a randomized, controlled trial. Birth. 1995;22(3):138–43.

Tripathy P, Nair N, Barnett S, Mahapatra R, Borghi J, Rath S, et al. Effect of a participatory intervention with women's groups on birth outcomes and maternal depression in Jharkhand and Orissa, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9721):1182–92.

Cupples ME, Stewart MC, Percy A, Hepper P, Murphy C, Halliday HL. A RCT of peer-mentoring for first-time mothers in socially disadvantaged areas (the MOMENTS study). Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(3):252–8.

Armstrong KL, Fraser JA, Dadds MR, Morris J. A randomized, controlled trial of nurse home visiting to vulnerable families with newborns. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35(3):237–44.

Morrell CJ, Spiby H, Stewart P, Walters S, Morgan A. Costs and effectiveness of community postnatal support workers: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000;321(7261):593–8.

Kemp L, Harris E, McMahon C, Matthey S, Vimpani G, Anderson T, et al. Child and family outcomes of a long-term nurse home visitation programme: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:533–40.

MacArthur C, Winter HR, Bick DE, Knowles H, Lilford R, Henderson C, et al. Effects of redesigned community postnatal care on women’s health 4 months after birth: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9304):378–85.

Dennis C-L, Hodnett E, Kenton L, Weston J, Zupancic J, Stewart DE, et al. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:a3064.

Lumley J, Watson L, Small R, Brown S, Mitchell C, Gunn J. PRISM (program of resources, information and support for mothers): a community-randomised trial to reduce depression and improve women's physical health six months after birth. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:37.

Carrick-Sen DM, Steen N, Robson SC. Twin parenthood: the midwife's role-a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2014;121(10):1302–10.

Waldenstrom U, Brown S, McLachlan H, Forster D, Brennecke S. Does team midwife care increase satisfaction with antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care? A randomized controlled trial. Birth. 2000;27(3):156–67.

Gunn J, Lumley J, Chondros P, Young D. Does an early postnatal check-up improve maternal health: results from a randomised trial in Australian general practice. BJOG. 1998;105(9):991–7.

Ashford MT, Olander EK, Ayers S. Computer- or web-based interventions for perinatal mental health: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;197:134–46.

Lee EW, Denison FC, Hor K, Reynolds RM. Web-based interventions for prevention and treatment of perinatal mood disorders: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:38.

Loughnan SA, Sie A, Hobbs MJ, Joubert AE, Smith J, Haskelberg H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of ‘MUMentum pregnancy’: internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy program for antenatal anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:381–90.

Loughnan SA, Butler C, Sie AA, Grierson AB, Chen AZ, Hobbs MJ, et al. A randomised controlled trial of ‘MUMentum postnatal’: internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety and depression in postpartum women. Behav Res Ther. 2019;116:94–103.

Dimidjian S, Goodman SH, Felder JN, Gallop R, Brown AP, Beck A. Staying well during pregnancy and the postpartum: a pilot randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2016;84(2):134–45.

National Statistical Service. High-level principles for data integration involving commonwealth data for statistical and research purposes. Canberra: Australian Government; 2010.

Matthey S, Agostini F. Using the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale for women and men-some cautionary thoughts. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2017;20(2):345–54.

Kozinszky Z, Dudas RB. Validation studies of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale for the antenatal period. J Affect Disord. 2015;176:95–105.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the health professionals from Sydney and South Western Sydney who enter this data as well as the staff from the Information Management & Technology department who generate this data for analysis. We are grateful to Dr. Alexandra Hendry who prepared the data for analysis and Professor Andrew Page and Professor Bin Jalaludin for his previous preparation of the database used for this publication. We are also grateful to Dr. Justine Noble and Jennifer Jones for their work examining an earlier cohort of women.

Funding

Felix A. Ogbo received early career research funding grant from the Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Research and Innovation), Western Sydney University, to conduct this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK contributed to the conceptualisation of the research question, analysed and interpreted results, drafted original manuscript and conducted critical revisions of the submitted manuscript. JE conceptualised the study idea and was responsible for obtaining the data and critically revising the manuscript as submitted. BB contributed to the conceptualisation of the research question, interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript as submitted. SN prepared the data and conducted the statistical analysis. FAO contributed to the conceptualisation of the research question, conducted the analysis, interpreted results and critically revised the manuscript as submitted. All authors have read and approved this final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained by both:

South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee: HREC: LNR/11/LPOOL/463; SSA: LNRSSA/11/LPOOL/464 and Project No: 11/276 LNR.

Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee: Protocol No X17–0454 and LNR/12/RPAH/266.

No individuals were contacted for this study therefore participant consent was not obtained.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Khanlari, S., Eastwood, J., Barnett, B. et al. Psychosocial and obstetric determinants of women signalling distress during Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) screening in Sydney, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 407 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2565-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2565-3