Abstract

Background

Antenatal care provides the best opportunity to promote maternal and child health services use. But many Ethiopian mothers deliver at home and fail to attend postnatal care. Therefore, this study was done to identify factors associated with health facility delivery among mothers who attended four or more antenatal care visits. The study was also intended to identify factors associated with postnatal care service use among mothers who delivered at home after four or more antenatal care visits.

Methods

This study used the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data. Two thousand four hundred fifteen women who attended four or more antenatal care visits were included to identify factors associated with health facility delivery after four or more antenatal care visits. Among them, 1055 mothers delivered at home. These women were included to identify factors associated with postnatal care service use. Stata 15.1 was used to analyze the data. Multivariable logistic regression model was fitted to identify associations between the outcome and predictor variables.

Results

Among women who had four or more antenatal care visits, 56% delivered at health facility. Mothers with secondary or higher level of education (AOR = 2.9; 95% CI = 1.6–5.3), urban residents (AOR = 3.4; 95% CI = 1.9–6.1), women with highest wealth quintile (AOR = 2.7; 95% CI = 1.5–4.8), and working women (AOR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2–2.3) had higher odds of delivering at health facilities. High birth order (AOR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.3–0.7) was negatively associated with a lower likelihood of health facility delivery. Among women who delivered at home, only 8% received postnatal care within 42 days after delivery. Only the content of care received during antenatal care visits (AOR = 1.40; 95% CI = 1.1–1.8) was significantly associated with postnatal care attendance.

Conclusion

Women with lower socio-economic status had lower odds of giving birth at health facility even after attending antenatal care. The more antenatal care components a mother received, the higher her probability of delivering at health facility. Similarly, postnatal care attendance was higher among women who had received more antenatal care components.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Although preventable with proven, cost-effective interventions, maternal mortality is global public health problem [1, 2]. Antenatal care (ANC), skilled attendant at delivery and postnatal care (PNC) are some of these effective interventions [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Antenatal care is an opportunity for health care providers to detect and treat causes of maternal mortality. When the number of ANC visits increases, the woman is expected to acquire more knowledge and develop better attitude about using other maternal health services [10,11,12,13]. Studies recommended four or more focused visits for antenatal care to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes [14, 15]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of evidences in sub-Saharan African countries documented that mothers who attended at least four ANC visits were seven times more likely to deliver in health facility [16]. Another study among four African countries reported a positive effect of the number of ANC consultations with use of a skilled birth attendant [17]. Studies in Colombia, Nepal, Bangladesh, Zambia, and Kenya showed similar finding [18,19,20,21,22]. A study conducted in Debremarkos town, Northwest Ethiopia, reported that women who attended four or more ANC visits were five times more likely to deliver in health facility compared with women who attended fewer visits [23].

Ethiopia had developed many strategies and programs to improve maternal health services use. For example, family planning, ANC, facility delivery, and PNC services are provided free of charge [10, 24,25,26,27]. Regardless of these efforts, health facility delivery service use (26%) and PNC uptake (17%) remained very low. This low facility delivery and PNC services use was observed although there was improvement in ANC service use from 27% in 2000 to 62% in 2016) [28]. Improvement in ANC service use is expected to improve facility delivery and postnatal care services use by enhancing behaviors beneficial to the mother and her child including delivering in health facility and using postnatal care services. Why institutional delivery and postnatal care services use remained low while antenatal care services use is relatively high in Ethiopia was not clear. The available studies in Ethiopia are small to answer this question. Therefore, this study was done to identify factors associated with health facility delivery service use among mothers who attended four or more ANC visits. The study also intended to identify factors associated with PNC service use among mothers who delivered at home after attending four or more ANC visits. Answering this question will help policymakers and programmers to improve the continuity of care from antenatal to facility delivery and postnatal care service use.

Methods

Data

This study used the 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey data, which was collected by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA), Ethiopia and the DHS Program, ICF [42]. The 2016 EDHS sample design had two stages. In the first stage, each region was stratified into urban and rural areas. Then, clusters were selected from both rural and urban areas using a probability proportional to size allocation. A list of all the households was prepared in all the selected clusters. In the second stage, a fixed number of households were selected systematically from the selected clusters. Then, all women age 15–49 years in the selected households were included.

The following criteria were used to select women to be considered in the analysis:

-

Women who had at least one birth five years before the interview

-

Women who attended four or more antenatal care visits during the most recent pregnancy

Of the total 15,683 women included in the 2016 EDHS, 2415 attended four or more ANC visits for the most recent birth. These women were included in the analysis to identify factors associated with facility delivery. From these, 1055 mothers delivered at home. Only these women were included to identify factors associated with postnatal care service use among mothers who delivered at home after four or more ANC visits (Fig. 1). Women who delivered at home were the interest of this analysis for PNC service use because women who delivered at health facility were more likely to receive postnatal care even though the care was likely to be initiated by health care providers and thus does not measure women’s health seeking behavior [29,30,31,32].

Measurements

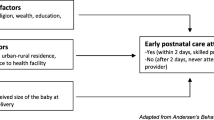

The outcome variables for this analysis were place of delivery and postnatal care attendance.

The independent variables for this study were:

-

Socio-demographic characteristics: maternal age at the time of birth of the most recent child, religion, educational status, marital status, place of residence (urban-rural), household wealth quintile and working status of the mother.

-

Fertility related characteristics: birth order of the recent child, and whether the pregnancy was wanted or not.

-

ANC service-related characteristics: mother’s perceived distance of the nearest health facility, components of antenatal care- measured by computing a summative composite score from the following antenatal components: blood pressure measurement taken, urine sample taken, blood sample taken, mother told about pregnancy complications, mother told about birth preparedness plan, and mother received nutrition counseling. For each of the component indicators, a woman received a point if she received the component. A total composite score was created by summing up the points for all six indicators. The total score ranged from zero to six where zero represents that the woman received none of the six antenatal care components and six when the woman received all components.

Analytical methods

Data were analyzed using Stata 15.1. Sample weight was applied when computing frequencies. Descriptive statistics was used to describe the characteristics of mothers. Multicollinearity was checked using variance inflation factors (VIF). Binary logistic regression was used to identify predictors of health facility delivery and postnatal care service use among mothers who attended four or more ANC visits. All variables entered in the bivariate model were entered to the multivariable model.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 2415 mothers who had attended four or more antenatal care visits for the most recent birth in the five years before the survey were included in the analysis. The mean age of the mothers was 26.9 years. About two-third of the mothers were rural residents. Almost all (93%) were either married or in union. More than half (69%) were Christians in terms of religion. Regarding the level of education, about half of the mothers (48%) did not attend formal education. The majority of mothers (66%) had no formal job. Considering the wealth index, 30% mothers were in the richest wealth quintile. Other characteristics of the women are shown in table below (Table 1).

Health facility delivery among women who attended four or more antenatal care visits

Among women who attended four or more ANC visits, 56% delivered at health facility. The table below shows the characteristics of women who delivered at health facility after four or more ANC visits (Table 2).

Factors associated with health facility delivery after four or more antenatal care visits

The binary logistic regression model showed that educational status, place of residence, wealth index, mother’s working status, birth order, and components of ANC were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with health facility delivery among women who attended four or more ANC visits. Mothers who had completed secondary and tertiary level of education had 2.9 times (95% CI: 1.6–5.3) higher odds of health facility delivery compared to mothers who had no formal education. Urban resident mothers had 3.4 times (95% CI: 1.9–6.1) higher odds of health facility delivery compared to rural women. Women in the richest wealth quintile had 2.7 times (95% CI: 1.5–4.8) higher odds of using health facility delivery compared to mothers in the poorest quintile.

Mothers who were working outside home at the time of interview had 1.6 times (95% CI: 1.2–2.3) higher odds of delivering at health facility compared to non-working mothers. Women with 2–4 birth orders had 50% (95% CI: 0.3–0.7%) lower odds of delivering at health facility compared to first-order births. Similarly, women with birth order of five or more had 70% (95% CI: 0.2–0.6) lower odds of delive ring at health facility compared to women with first-order births. An increase in receiving components of ANC improves the odds of health facility delivery by 30% (95% CI: 1.2–1.4) (Table 3).

Characteristics of women who delivered at home after four or more antenatal care visits

Among mothers who attended four or more ANC visits, 44% delivered at home. Table 4 below shows the characteristics of women who delivered at home after four or more ANC visits.

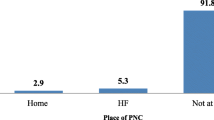

Postnatal care (PNC) among mothers who delivered at home after four or more ANC visits

Among women who gave birth at home after attending four or more ANC visits, only 8% (95% CI: 6.1–11.5%) attended postnatal care. There was variation in PNC attendance by socio-demographic characteristics (Table 5).

Factors associated with postnatal care attendance among women who delivered at home after four or more antenatal care visits

From all the variables included in the multivariable logistic regression model, only the number of ANC components a woman received during antenatal care was significantly associated with postnatal care services use. A one unit increase of one component of ANC improves the odds of using postnatal care service by 40% (95% CI: 10–80%) (Table 6).

Discussion

Health facility delivery among women who attended four or more antenatal care visits

The analysis revealed that among women who attended four or more ANC visits, over half of them gave birth at health facility. This level of health facility delivery service use is low compared to the national target of 95% deli very attendance with a skilled provider by 2020 [33, 34]. Currently available evidences reported that mothers who attended four or more ANC visits are more likely to be informed and aware of the importance of health facility delivery. These women already won the challenges of visiting health facility. Therefore, they are expected to give birth in health facilities. However, the finding of this study contradicts this assumption. The possible reasons for low health facility delivery service use among women who attended four or more ANC visits may be the poor quality of information provided during antenatal care sessions. The other reasons may be the women’s perceived poor quality of delivery care provided at the health facilities. If women rated the quality of delivery service low, they are less likely to give birth at health facility although they attended ANC.

Mothers who completed secondary or higher level of education had higher odds of giving birth at health facility compared to mothers who did not attend formal education. This finding was similar with studies conducted in Nepal, Cambodia, and a meta-analysis in Ethiopia [19, 21, 35]. Higher level of education is associated with better information processing skill, improved cognitive skills and values, exerting effects on health seeking behavior through different pathways. These pathways include higher level of awareness and better knowledge of maternal health services and enhanced level of autonomy. Education increases feelings of self-worth and confidence which all improve health service use [36, 37].

Urban mothers had higher odds of giving birth at health facility compared to rural mothers. This finding was similar with studies conducted in Ethiopia and Ghana [35, 38]. Urban women have better exposure to media regarding the benefits of facility delivery. Cultural barriers related with health service use are less prevalent in urban areas compared to rural areas [39]. Similarity, accessibility and quality of health services may be better in urban settings. Urban women are also more educated than rural woman [40,41,42].

The analysis revealed that women in the richest wealth quintile had higher odds of giving birth at health facilities compared to poorest women. This finding was consistent with other studies [19, 21, 43]. The cost of health facility delivery may not be the reason in Ethiopia because all maternal health services are provided free of charge. However, other costs such as transport, time spent by the mother and family members at the hospital, and fear of unofficial payments, could help explain the lower odds of giving birth at health facilities among the poor. Working mothers had higher odds of delivering at health facility. This finding was consistent with previous reports [44]. The reason for this is that working mothers are more likely to be autonomous for health services use. They are also more likely to receive information at work that promotes health facility delivery service use [45,46,47].

Second and higher order births had lower odds of being delivered at health facility compared to first order births. This finding was consistent with other studies [19, 21] but contradicts a study conducted in Ethiopia. Higher order births are more likely to be unwanted, which in turn could affect the use of maternal health services [48,49,50,51]. Another possible explanation for lower odds of being delivered at health facilities for higher order births is that mothers could be fearful during first birth and hence more likely to use health facility for delivery for the first birth than subsequent births [52, 53]. In addition, women in the younger generation initiating childbearing are more educated than the older generation.

Mothers who received more ANC components had higher odds of delivering at health facility. This finding was similar with studies conducted in Mexico and Cambodia [21, 54]. Currently available evidences indicate that better quality ANC service is associated with higher health facility delivery service use. The number of ANC components a woman received during ANC can be considered as a proxy indicator for the quality of ANC.

Factors associated with postnatal care attendance among women who delivered at home after four or more ANC visits

Postnatal care attendance among mothers who delivered at home after four or more ANC visits was very low compared with the national child survival strategy and the health sector transformation plan targets for 2020 [33, 34]. Among women who attended four or more ANC visits and delivered at home, only 8% attended postnatal care. This implies that mothers were not using postnatal care services although they managed all the challenges of attending the recommended number of ANC visits.

Mothers who received more ANC components had higher odds of attending PNC. Receiving more ANC components implies that the mother is more likely to be informed about complications that may occur after delivery and thus recognize the importance of timely postnatal care.

Conclusions

Health facility delivery service use among women who attended four or more ANC visits was still low in Ethiopia. Women with higher socioeconomic status (richest, working, educated, and urban) had higher odds of delivering at health facility. In addition, the more ANC components women received, the more likely she give birth at health facility and attend postnatal care services. Further studies on how continuity of care following ANC is associated with socio-economic status and components of ANC care are required.

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CSA:

-

Central statistical agency

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian demographic and health survey

- HIV:

-

Human immuno-deficiency virus

- PNC:

-

Postnatal care

- VIF:

-

Variance inflation factors

References

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, The United Nations Population Division. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division 2015.

Black RE, Levin C, Walker N, Chou D, Liu L Temmerman M. Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: key messages from disease control priorities 3rd edn. Lancet 2016;388(10061):2811–2824.

You DH, Ejdemyr L, Idele S, Hogan P, Mathers D, Gerland C, New P, Rou J, Leontine A. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in under-5 mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN inter-agency group for child mortality estimation. Lancet. 2015;386(10010):2275–86.

Chou D, Daelmans B, Jolivet RR, Kinney M, Say L. Ending preventable maternal and newborn mortality and stillbirths. BMJ. 2015;351:h4255.

WHO. Strategies towards ending preventable maternal mortality (EPMM). 2015.

Bustreo F, Say L, Koblinsky M, Pullum TW, Temmerman M, Pablos-Méndez A. Ending preventable maternal deaths: the time is now. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(4):e176–e7.

Wani RJ, Chikhal P, Sonwalkar D. Maternal mortality: preventable tragedy. Bombay Hospital J. 2009;51(4):426–39.

Hezelgrave NL, Duffy SP, Shennan AH. Preventing the preventable: pre-eclampsia and global maternal mortality. Obstetrics, Gynaecology and Reproductive Medicine. 2012;22(6):170–2.

Annan KA. Maternal health: investing in the lifeline of healthy Societies & Economies: Africa progress panel; 2010.

Lawn J, Kerber K. Opportunities for Africa's newborns. Cape Town: The Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. 2006;246.

Moos MK. Prenatal care: limitations and opportunities. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2006;35(2):278–85.

Stephenson P. Focused antenatal care: a better cheaper faster evidence-based approach; 2005.

WHO. Antenatal care randomized trial: manual for the implementation of the new model. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2002;37.

Munjanja SP, Lindmark G, Nyström L. Randomised controlled trial of a reduced-visits programme of antenatal care in Harare. Zimbabwe The Lancet. 1996;348(9024):364–9.

Villar J, Ba'aqeel H, Piaggio G, Lumbiganon P, Belizán JM, Farnot U, et al. WHO antenatal care randomised trial for the evaluation of a new model of routine antenatal care. Lancet. 2001;357(9268):1551–64.

Berhan Y, Berhan A. Antenatal care as a means of increasing birth in the health facility and reducing maternal mortality: a systematic review. Ethiopian journal of health sciences. 2014;24:93–104.

Adjiwanou V, LeGrand T. Does antenatal care matter in the use of skilled birth attendance in rural Africa: a multi-country analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2013;86:26–34.

Trujillo JC, Carrillo B, Iglesias WJ. Relationship between professional antenatal care and facility delivery: an assessment of Colombia. Health Policy Plan. 2013;29(4):443–9.

Tamang TM. Factors associated with completion of continuum of Care for Maternal Health in Nepal; 2017.

Pervin J, Moran A, Rahman M, Razzaque A, Sibley L, Streatfield PK, et al. Association of antenatal care with facility delivery and perinatal survival–a population-based study in Bangladesh. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2012;12(1):111.

Wang W, Hong R. Levels and determinants of continuum of care for maternal and newborn health in Cambodia-evidence from a population-based survey. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2015;15(1):62.

Do M, Hotchkiss D. Relationships between antenatal and postnatal care and post-partum modern contraceptive use: evidence from population surveys in Kenya and Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):6.

Kasaye HK, Endale ZM, Gudayu TW, Desta MS. Home delivery among antenatal care booked women in their last pregnancy and associated factors: community-based cross sectional study in Debremarkos town, north West Ethiopia, January 2016. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2017;17(1):225.

Zelelew H. Health care financing reform in Ethiopia: improving quality and equity; 2014.

FDRE. National Reproductive Health Strategy 2014–2018. In: Minstry of Health E, editor. Addis Ababa2014.

Banteyerga H. Ethiopia's health extension program: improving health through community involvement. MEDICC review. 2011;13(3):46–9.

Karim AM, Admassu K, Schellenberg J, Alemu H, Getachew N, Ameha A, et al. Effect of Ethiopia’s health extension program on maternal and newborn health care practices in 101 rural districts: a dose-response study. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65160.

CSA, ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF: 2016.

Rwabufigiri BN, Mukamurigo J, Thomson DR, Hedt-Gautier BL, Semasaka JPS. Factors associated with postnatal care utilisation in Rwanda: a secondary analysis of 2010 demographic and health survey data. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2016;16(1):122.

Limenih MA, Endale ZM, Dachew BA. Postnatal care service utilization and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last 12 months prior to the study in Debre Markos town, northwestern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. International journal of reproductive medicine. 2016;2016.

Chungu C, Makasa M, Chola M, Jacobs CN. Place of delivery associated with postnatal care utilization among childbearing women in Zambia. Front Public Health. 2018;6:94.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Minstry of Health. Newborn Care Training Participants Manual. 2012.

Maternal and Child Health Directorate Federal Ministry of Health. National Strategy for Newborn and Child Survival in Ethiopia 2015/16–2019/20. In: Directorate MaCH, editor. Addis Ababa 2015.

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health. The Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015/16–2019/20. 2015.

Alemi Kebede KH, Teklehaymanot AN. Factors associated with institutional delivery service utilization in Ethiopia. Int J Women's Health. 2016;8:463.

Schultz TP. Studying the impact of household economic and community variables on child mortality. population and Development Review. 1984;10:215–35.

Chanana K. Educational attainment status production and womens autonomy: a study of two generations of Punjabi women in New Delhi; 1996.

Dickson KS, Adde KS, Amu H. What influences where they give birth? Determinants of place of delivery among women in rural Ghana. International journal of reproductive medicine. 2016;2016.

Ansu-Kyeremeh K. Rural Women’s Exposure to Health Messages and Understandings of Health. Journal of Healthcare Communications. 2016;1(3).

Ganle JK, Parker M, Fitzpatrick R, Otupiri E. Inequities in accessibility to and utilisation of maternal health services in Ghana after user-fee exemption: a descriptive study. Int J Equity Health. 2014;13(1):89.

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA CSA and ICF; 2016.

Tafere TE, Afework MF, Yalew AW. Antenatal care service quality increases the odds of utilizing institutional delivery in Bahir Dar city administration, North Western Ethiopia: a prospective follow up study. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192428.

Montagu D, Yamey G, Visconti A, Harding A, Yoong J. Where do poor women in developing countries give birth? A multi-country analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17155.

Gabrysch S, Campbell OM. Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2009;9(1):34.

Adhikari R. Effect of Women’s autonomy on maternal health service utilization in Nepal: a cross sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):26.

Pandey KK, Singh R. Womens status, household structure and the utilization of maternal health Services in Haryana (India); 2017.

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Minstry of Health. National Health Promotion and Communication Strategy, 2016-2020. 2016.

Goto A, Yasumura S, Reich MR, Fukao A. Factors associated with unintended pregnancy in Yamagata, Japan. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(7):1065–79.

Theme-Filha MM, Baldisserotto ML, Fraga ACSA, Ayers S, Gama SGN, do Carmo Leal M. Factors associated with unintended pregnancy in Brazil: cross-sectional results from the Birth in Brazil National Survey, 2011/2012. Reproductive health. 2016;13(3):118.

Eggleston E. Unintended pregnancy and women’s use of prenatal care in Ecuador. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(7):1011–8.

Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79(3):194–8.

Toohill J, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK. Prevalence of childbirth fear in an Australian sample of pregnant women. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2014;14(1):275.

Hanna-Leena MR. Experiences of fears associated with pregnancy and childbirth: a study of 329 pregnant women. Birth. 2002;29(2):101–11.

Barber S. Does the quality of prenatal care matter in promoting skilled institutional delivery? A study in rural Mexico. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10(5):419–25.

Acknowledgements

We are appreciative of the 2018 DHS Fellows Program facilitators, Wenjuan Wang and Shireen Assaf, who immensely assisted us on the overall development of the research project and provision of training on DHS data analysis. We would like to acknowledge the effort of the co-facilitators, Henock Yebyo and EhabSakr, for their support on DHS data analysis skills. We would like to extend our appreciation to the 2018 DHS fellows for their constructive feedback during the entire training sessions. We are also thankful to Bahir Dar University for allowing us to attend the DHS 2018 Fellows Program. Our acknowledgment also goes to ICF for organizing the 2018 DHS fellows’ workshop. We are thankful to reviewers Lindsay Mallick and Courtney Allen for their constructive comments on the paper, and to the editor, Bryant Robey, and formatter of this manuscript. The first draft of this manuscript was uploaded in BioRXiv as preprint. The authors would like to thank BioRXiv for that.

Funding

This study was carried out with support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through The DHS Program (#AID-OAA-C-13-00095). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID has no role in the interpretation of the results.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available in the DHS program repository, available at https://dhsprogram.com/data/dataset_admin/login_main.cfm?CFID=15716167&CFTOKEN=12841bb47e96d711-949548D7-BAFB-A4AB-230A91882FEC6B8Eupon permission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GAF, FA and SAK contributed in the design of the study. All authors were involved in the analysis and write up of the study. All authors approved and agreed the submission of this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

GAF is assistant professor in reproductive health in Bahir Dar University and PhD fellow in Pan African University, Institute of life (including Health and agriculture) and earth Sciences, University of Ibadan. FA is associate professor of public health in Bahir Dar University and a post-doctoral fellow of African Mental Health Research Initiative (AMARI) at Addis Ababa University. He earned his PhD in mental health epidemiology. SAK is also assistant professor of social works in Bahir Dar University. She earned her PhD in social work and development from Addis Ababa University and currently head of the department.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethiopian Demographic and health survey obtained written informed consent from all the participants during the data collection. Data were collected anonymously. The survey secured ethical clearance from the Ethiopian national Ethics review committee. Permission was obtained to analyze this data from the DHS program.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fekadu, G.A., Ambaw, F. & Kidanie, S.A. Facility delivery and postnatal care services use among mothers who attended four or more antenatal care visits in Ethiopia: further analysis of the 2016 demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2216-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2216-8