Abstract

Background

Fear of Childbirth (FOC) is a common problem affecting women’s health and wellbeing, and a common reason for requesting caesarean section. The aims of this review were to summarise published research on prevalence of FOC in childbearing women and how it is defined and measured during pregnancy and postpartum, and to search for useful measures of FOC, for research as well as for clinical settings.

Methods

Five bibliographic databases in March 2015 were searched for published research on FOC, using a protocol agreed a priori. The quality of selected studies was assessed independently by pairs of authors. Prevalence data, definitions and methods of measurement were extracted independently from each included study by pairs of authors. Finally, some of the country rates were combined and compared.

Results

In total, 12,188 citations were identified and screened by title and abstract; 11,698 were excluded and full-text of 490 assessed for analysis. Of these, 466 were excluded leaving 24 papers included in the review, presenting prevalence of FOC from nine countries in Europe, Australia, Canada and the United States. Various definitions and measurements of FOC were used. The most frequently-used scale was the W-DEQ with various cut-off points describing moderate, severe/intense and extreme/phobic fear. Different 3-, 4-, and 5/6 point scales and visual analogue scales were also used. Country rates (as measured by seven studies using W-DEQ with ≥85 cut-off point) varied from 6.3 to 14.8%, a significant difference (chi-square = 104.44, d.f. = 6, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

Rates of severe FOC, measured in the same way, varied in different countries. Reasons why FOC might differ are unknown, and further research is necessary. Future studies on FOC should use the W-DEQ tool with a cut-off point of ≥85, or a more thoroughly tested version of the FOBS scale, or a three-point scale measurement of FOC using a single question as ‘Are you afraid about the birth?’ In this way, valid comparisons in research can be made. Moreover, validation of a clinical tool that is more focussed on FOC alone, and easier than the longer W-DEQ, for women to fill in and clinicians to administer, is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Being pregnant and giving birth are described as a transition phase, or an existential threshold that childbearing women have to cross [1]. Childbirth is an experience with many dimensions, multifaceted and unique for each woman, still strongly influenced by her social context [2]. Women’s expectations and experiences of pregnancy and birth are both positive and negative in nature, involving feelings of joy and faith but also worries, anxiety and fears. Despite the fact that maternity care in high income countries is safe, fear of childbirth is a common problem affecting women’s health and wellbeing before and during pregnancy, as well as after childbirth. Fear of childbirth has consequences for women’s relationships with their baby, partner and family [3], and often leads to requests for caesarean section (CS) by women striving for control in an exposed situation [4,5,6,7].

During the last few decades there has been a growing research interest in women’s fear of childbirth. For some women, the fear only relates to childbirth, but for others fear occurs in relation to other types of anxiety also [3, 8]. Fear of parturition is not new, and was described by the French psychiatrist Louis Victor Marcé (1858) [9]. The term ‘fear of childbirth’ (FOC) was characterised in 1981 in a population of Swedish pregnant women, defined as: “a strong anxiety which had impaired their [the women’s] daily functioning and wellbeing” [10, p. 265]. In addition, a more moderate fear was described as a significant anxiety, which did not interfere with the women’s daily life [10]. Later, during the 1990s, studies from Finland defined FOC as a health issue for a pregnant woman related to an anxiety disorder or a phobic fear including physical complications, nightmares and concentration problems, as well as demands for caesarean section [11]. The term ‘clinical FOC’ describes a “disabling fear that interferes with occupational and domestic functioning, as well as social activities and relationships”, and in some cases even reaches the classification for a specific phobia according to the DSM IV [3, p. 141]. The label “tokophobia” is also used [12, 13], characterised as an “unreasoning dread of childbirth” in women, a “specific and harrowing condition” [12, p. 83] including a “pathological dread” and “avoidance of childbirth” [13, p. 506]. Moreover, FOC is strongly related to the increasing caesarean section (CS) rates in Western countries, as being a common cause for women requesting a surgical birth [14, 15].

In early studies, the prevalence of FOC for pregnant women in Scandinavia was reported as 20%, with approximately 5–10% women experiencing intense fear [10]. The prevalence in Europe seems to vary between countries, from 1.9–14% [16], while Australia indicates higher rates of around 30% [17], leaving questions on possible cultural differences in FOC, or differing definitions. However, the variations in prevalence can also depend on the measures used; these can vary from fear being self-defined by women, or self-reported via different questionnaires, or estimated through measurement of physiological indices such as stress hormones in childbirth [3, 18, 19].

For women lacking experience of childbirth (so called primary tokophobia or FOC), their fears may date from adolescence or early adulthood, where experiences of others’ fearful responses to childbirth or a history of anxiety disorders could be important [8, 12, 13]. Secondary tokophobia or FOC is related to the event of birth, and is usually linked to fears developed after a previous negative or traumatic experience of childbirth, sometimes related to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [3, 8, 11,12,13]. Tokophobia is also described as a symptom of prenatal depression [12, 13]. However, the research on FOC has been criticised for constructing women’s fear as a medical category, having too pathological an approach that searches for errors in women, instead of examining possible causes of women’s fear within maternity care itself [20, 21].

To summarise, the research field is extensive, complex, and difficult to survey without any consensus on definitions. The concept “fear of childbirth” seems to be used as a broad label for all kinds of anxiety and fears that women experience in relation to pregnancy and childbirth. Relevant questions are: How common is FOC? Are there any cross cultural differences? Which measures are pertinent? What is FOC? There is a need for systematic reviews on FOC to be able to direct future research on developing optimal care and effective treatment for women fearing childbirth and to identify factors that reduce, as well as increase, women’s fears. Therefore, as a first step, we conducted a systematic review of all studies demonstrating a prevalence of FOC. The aims of this review were to identify the prevalence of FOC in childbearing women and how it is defined and measured during pregnancy and postpartum, and to search for useful measures of FOC, for research as well as for clinical settings.

Methods

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants

Participants were childbearing women (defined as the period covering pregnancy, labour and birth, and the first year postpartum).

Types of studies

Surveys, cross-sectional studies, experimental and quasi-experimental studies (where the control group could provide data), observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, were eligible for inclusion.

Types of outcome

The primary outcome was prevalence of fear of childbirth, where this was defined clearly by study authors. Papers measuring fear during labour were excluded. Many studies used the same population (i.e., a number of PhD students accessed the same population at the same time and conducted different studies, but reported the same prevalence). We only included studies that were the first to report prevalence in a population and at similar time points. Studies reporting the same prevalence, on the same population or on a subsample (less representative, were excluded.

Search and selection strategy

A search strategy was developed and reviewed for accuracy, by one member not involved in its development (CS-L), using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) criteria [22]. No restrictions were applied to years searched, but papers included were limited to English and Swedish publications only. We searched electronic bibliographic databases of The Cochrane Library, PubMed, Scopus, PsycINFO and CINAHL from their inception dates, in March 2015, using the agreed search strategy as described in Additional file 1.

Selection of studies

Studies were selected for inclusion from the papers identified, by team members working in pairs, using the above criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by a third member.

Quality assessment of included studies

The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool [23] was chosen to assess methodological quality of all studies included. Components of study design and methods assessed by this tool include selection and allocation bias, confounding, blinding, methods of data collection, withdrawals/drop-outs and analysis and intervention integrity. As some dimensions of the EPHPP (e.g. the sections on confounding and intervention integrity) are not relevant for reviews of non-intervention studies, the tool did have some shortcomings. For example, following discussion, it was agreed by the team to rate all cross-sectional studies (single cohort) as moderate, to avoid studies of otherwise good quality being excluded. Despite these problems, the tool was useful, especially for identifying ‘Weak’ experimental studies and excluding them. An overall quality rating was assigned to each study following assessment, of Strong (where no weak ratings were assigned), Moderate (one weak rating) or Weak (two or more weak ratings). An a priori decision was made that studies receiving a ‘Weak’ global rating score would be excluded from analysis. Team members in pairs assessed the quality of included studies. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved by consensus, or by a third member of the review team if necessary. In addition, as one of the team-members was co-author in some of the studies, those were assessed by other members of the review team.

Data extraction and analysis

Using a pre-designed data extraction form, data on prevalence, definitions and measurements were extracted independently by each member of the four review teams and checked for accuracy by the other reviewer.

Due to the differing types of studies, it was seldom possible to combine results into a meta-analysis. A narrative synthesis was provided instead.

Results

Results of search and selection strategy

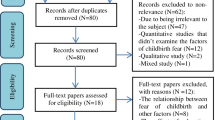

In total, 18,464 citations were identified using the search strategy designed. After removing duplicates, 12,188 unique citations were screened by title and abstract and 11,698 excluded. Full-text papers of the remaining 490 citations were read and 354 of these were subsequently excluded, leaving 136 for inclusion (Fig. 1).

Methodological quality of included studies

The 136 papers were assessed and 76 were rated as “Weak”, and therefore excluded. The main reasons for “Weak” ratings were that the samples were unlikely to be representative of the population and the data collection tools were either not tested for validity, or there was insufficient information on their testing. This resulted in 60 papers meeting the inclusion criteria for this review (Fig. 1). At data extraction stage, however, it was clear that, for nine of the papers, no prevalence data could be identified [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], for six others, the whole sample of women had FOC [33,34,35,36,37,38], 11 papers were qualitative [39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49], and 10 papers had double reporting or reported the prevalence of a subsample of a population already included in the review [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]; these were excluded leaving a total of 24 papers for inclusion, based on data from 23 study populations (two papers [60, 61] presented FOC during pregnancy and postpartum, based on the same population) (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Thirteen of these had been rated as methodologically “Strong” and 11 were rated as “Moderate” (Table 1).

Description of studies

The studies had been conducted in twelve countries, with Sweden emerging as the country with the most research into FOC (Table 1). Ten papers (reporting on nine studies) were from Sweden (one of which also included a cohort of women from Australia), two from Norway, four from Finland, two from Denmark, two from the United States of America, and one each from Canada, Australia, Switzerland, and Croatia. One study had included data from six countries: Belgium, Norway, Iceland, Denmark, Estonia, and Sweden [62]. The majority (n = 20) had collected data using either postal or self-completed and personally returned surveys, one in the post-natal period, 16 in the antenatal period and six at both time periods. Two studies used telephone interviews, one in the third trimester of pregnancy and 1 month after birth [63] and the second in early and late pregnancy [64]. One study used a randomised controlled trial methodology and we used the data from the population screened by W-DEQ to identify FOC in early pregnancy, prior to trial entry [65]. One study [66] used a retrospective analysis of a national database to gather data on FOC, defined according to ICD code 099.80 (Table 1). Sample sizes ranged from 200 to 788,317.

Eight papers were published based on studies using the same population, with surveys administered at four time-points, and care has been taken to ensure that rates have not been double-counted. Of these eight papers we only included three [60, 61, 67]; the others were excluded due to repeated prevalence reporting or because they reported on a subsample of a previously reported population [50,51,52,53,54]. Hildingsson et al. 2010 [60] included 1212 women and presented the results for FOC in mid-pregnancy, and Nilsson et al. [61] used the same sample, but presented the results for FOC in women 1 year after birth (n = 763). Haines et al. [67] took a sub-set of 386 women from the full population, who had attended one regional hospital, and recruited 122 Australian women also. As a VAS was used for the response format, these results are presented separately and are not merged with any other.

Definitions and measurements of FOC used by included studies

Eleven papers used the W-DEQ questionnaire, an instrument specifically designed to measure fear of labour and birth (Table 2). It consists of a 33-item questionnaire, and can be scored from 0 to 165 [68]. Various different cut-off points are used to define ‘severe fear of birth,’ from scores of ‘66 or greater’ to ‘greater than 100’, which makes comparison of prevalence difficult.

The authors of two papers [64, 69] used a 3-point scale to measure fear/anxiety about birth, in answer to similar questions relating to FOC (Table 2). The three response options were variously expressed as: “no, I am not afraid/not at all;” “yes, I am a bit afraid/yes, a little;” “yes, I am very afraid/yes, a lot,” respectively, which were deemed suitable to merge (Table 2). Their definition of severe FOC was thus “yes, I am very afraid/yes, a lot.” Laursen et al. [64] measured FOC in both early and late pregnancy, but as the other authors, Geissbuehler and Eberhard [69], measured FOC in late pregnancy only, a combination of the late pregnancy rates was made.

A question with a four-point response scale was used in a study of a Swedish population, reported by Hildingsson et al. [60], and Nilsson et al. [61], with all their data coming from the same cohort of women and using similar questions relating to FOC; “to what extent do you experience worries and fear?”, With the addition of “when thinking of coming births” in the questionnaire 1 year after birth (Table 2). The authors dichotomised the scale into ‘no fear’ and ‘fear’. ‘No fear’ was described variously as ‘not at all + very little’ and ‘not at all + somewhat’, and ‘fear’ was described as ‘a lot + very much’ and ‘a great deal + very much’ (Table 2).

The remaining papers used a heterogeneous mix of various scales for measurement, none of which could be combined. Elvander et al. [63] graded fear on a 5-point scale, where women answered 6 questions on feeling: ‘nervous,’ ‘worried,’ ‘fearful,’ ‘relaxed,’ ‘terrified,’ and ‘calm’, in relation to their impending birth. Scores were divided into 3 categories: 6–13 (low fear), 14–20 (intermediate fear) and 21–30 (high fear, their definition of FOC). Waldenström et al. [70] also assessed FOC on a 5-point rating scale using the single question: “How do you feel when thinking about labour and birth?” Women ticking the “very negative” response alternative were defined as having childbirth related fear. Eriksson et al. [71] graded fear on a 6-point scale, from “no fear at all” to “very high fear.” Intense fear was defined as four or above and agreement with the statement that “childbirth-related fear influences your daily life in a negative sense” (Table 2).

Two studies [67, 72] used the Fear of Birth (FOBS) visual analogue scale but with different cut-off points (>50 and ≥60), so results could not be merged. The FOBS scale consists of one question – “How do you feel right now about the approaching birth?”- graded by marking two 100 mm visual analogue scales, which are anchored with the words “calm/worried” and “no fear/strong fear” [67].

Fabian et al. [73] asked women to answer one question on whether they had attended, or felt they needed to attend, a clinic for counseling in relation to FOC, to which they answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Lowe et al. [74] used a 15 item Childbirth Attitudes Questionnaire (high fear = 1 Standard Deviation above mean) and Poikkeus et al. [75] used a revised version of the Fear-of-Childbirth questionnaire, developed by Saisto et al. [76], and pregnancy anxiety scale. Total scores equal to or higher than the 90th percentile in the revised Fear-of-Childbirth questionnaire (total scores ≥6 and pregnancy anxiety scale, total scores ≥30) were considered “severe fear” and “severe pregnancy related anxiety” (Table 2). None of these results could be combined.

The majority of studies took measurements at only one time point or at varying times throughout pregnancy without comparing rates from different times. Laursen et al. [64] found rates in early pregnancy to be 2308 out of 30,480 (7.6%), similar to rates in late pregnancy, of 2245 out of 30,480 (7.4%). Postpartum rates of FOC were measured in only two studies [61, 77]. Due to differing measurement times and tools, no comparisons could be made but postpartum rates did not seem to differ greatly from those in the antenatal period (Table 2).

Prevalence

The prevalence of FOC varied, which may be due, in part, to the differing measurement scales. The most common scale was the W-DEQ, used in 11 studies, with four different cut-off points (some papers used more than one point). Three studies [65, 78, 79] used a cut-off point of greater than or equal to 100, with rates varying from 5.5 to 8.1%, giving an average ‘very severe’ FOC rate of 7.1% (536 out of 7531). A cut-off of greater than or equal to 85 in seven studies [62, 79,80,81,82,83,84] two cut-off levels gave FOC rates of 7.5% (165 out of 2206) to 15.5% (254 out of 1635), giving an average ‘severe’ rate of FOC of 11.1% (1545 out of 14,163) (Table 2). The final two studies using W-DEQ had cut-off points of greater than or equal to 66 [85] or 71 [77], which gave rates of ‘moderate’ FOC of 24.9 - 26.2% (Table 2).

The two studies using a 3-point scale [64, 69] had merged “extreme fear” FOC rates of 7.0% (2707 out of 38,801). The data collection using the dichotomised 4-point scale had rates (based on the same population) of 14% [60], in mid pregnancy, and 15.1% 1 year after birth [61] (Table 2).

Rates for the studies using 5- and 6-point scales [70, 71] varied considerably from 3.6 to 22.9%, and the 5-point scale was based on the question “How do you feel when thinking about labour and birth?” with the response “very negative” deemed to equate to FOC [70], which may not be accurate. Rates for all other prospective studies varied from 11 to 31.1%; the register study based on data from medical records [66] showed a rate of 28,960 out of 788,317 (3.7%) (Table 2).

Comparison of country rates

Rates of severe FOC in each country (as measured by seven studies using W-DEQ with ≥85 cut-off point) were combined, the average taken for each country, and then compared. The average rates varied from 6.3% in Belgium to 14.8% in Estonia, a significant difference in the seven countries (chi-square = 104.44, d.f. = 6, p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

Discussion

W-DEQ gave an average ‘very severe’ (greater than or equal to 100) FOC rate of 7.1%, severe (greater than or equal to 85) rate of 11.1%, and a ‘moderate’ rate of 25.3 - 26.2% (greater than or equal to 66 or 71). Merged rates from two studies [64, 69] using a question with a 3-point response scale and similar questions on fear (Table 2) had an average “extreme fear” rate in early pregnancy of 7%, very similar to the “very severe” rates measured by W-DEQ. The study using a similar question with a dichotomised 4-point Likert response scale (Table 2) had a rate in early pregnancy of 14.0% for fear or strong fear of childbirth [60].

Once W-DEQ cut-off points went below 85, or other scales had more than three (or four) points, the rates increased and also varied considerably from the average seen at the cut-off ≥85. This might indicate that using the W-DEQ tool with a cut-off point of ≥85, or a measurement of FOC using a single question such as ‘Are you afraid about the birth?’, with three responses such as ‘no, I am not afraid; yes, I am a bit afraid; yes, I am very afraid’ [69] would measure FOC equally but that needs further testing.

Rouhe et al. [86] have previously compared FOC levels in 1348 women using the 33-item W-DEQ scale (with a cut-off point of ≥85) with a one-item VAS scale, and a cut-off point of 5. Although there was some correlation they found it not to be as accurate as the W-DEQ, but pronounced it suitable for initial screening. Haines et al. [87] also compared the W-DEQ scale (using a cut-off point of ≥85) with the Fear of Birth scale (FOBS), a two-item VAS scale, involving 1410 women. Results showed a strong correlation. However, the FOBS’s cut-off point was 54, approximately equivalent to the cut-off of 5 used in their work examined here [67], which resulted in quite high FOC rates.

Using the question with a four-point Likert response scale appeared to over-estimate FOC rates, especially when results were dichotomised so that ‘extreme fear’ was merged with more moderate fear. Dichotomising results before analysis appears to be common, but ultimately does not produce useful results if a true measure of severe FOC is the main aim.

Rates of severe FOC, measured in the same way, varied in different countries from 6.3 to 14.8%. These results are new as, although one study in this review involved measuring FOC in six countries, no paper has analysed data from all seven countries where FOC has been measured. Reasons why FOC might differ in different countries are unknown, and further research in this field is required. One reason may be poor translation, or insufficient testing of the translated version of W-DEQ, both problems highlighted by previous authors [77, 88]. Another possible explanation is that some factors may remain unidentified when measuring with W-DEQ. For instance most scales measuring fear of childbirth do not consider important dimensions such as fear of abandonment by staff during birth [89], fear of medical interventions, loss of autonomy and control, as well as fear of mistreatment and obstetrical violence [90]. In addition, the W-DEQ scale assesses a range of emotions about labour and birth, where fear is only one emotion among many others. However, despite its shortcomings, the W-DEQ has been highlighted in a recent systematic review on validated instruments used for measuring women’s childbirth experiences as, currently, the best, most used and validated tool to measure FOC [91]. Culture-specific aspects in relation to fear of childbirth have been recognised in medicalised birth cultures, where young adults prefer CS over vaginal birth, and negative impressions of birth through visual media can be an important factor for generating fear [92, 93]. Moreover, traditions surrounding birth, women’s rights, how antenatal and maternity care is organised, CS rates, and which professions (midwives, GPs, obstetricians) are involved in pregnant and childbearing women’s care, could all influence women’s fear of childbirth.

As FOC has been shown in a large systematic review and meta-analysis to be strongly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder [94], simple and early diagnosis and intervention for women with severe FOC is recommended. Antenatal education, a relatively cheap and cost-effective intervention has been shown to decrease fear of childbirth [95, 96], as has cognitive behavioural therapy, although the sample size was small [97]. We therefore also examined the published tools to see which might be most useful in the clinical area. As shorter tools have greater clinical utility than the W-DEQ, a comparison between W-DEQ and a measurement of FOC using a single question with three or four responses (that are not dichotomised before analysis) would be useful in making decisions as to how best to measure FOC swiftly and accurately in the clinical location. A comparison between W-DEQ and the FOBS scale, possibly after further testing using a higher cut-off point, would also be very useful to the research and maternity care communities.

Conclusions

Rates of severe FOC, measured in the same way, varied in different countries. Reasons why FOC might differ are unknown, and further research is necessary. Using the W-DEQ tool with a cut-off point of ≥85, or a measurement tool using a single question with three responses, are consistent in measuring levels of severe FOC. Research comparing W-DEQ and a measurement tool using a single question with three responses, or four responses that are not dichotomised before analysis, would be useful to both the research and clinical communities. Similarly, continued and further testing of the FOBS scale, especially using a higher cut-off point to separate out “severe” FOC from more moderate levels, could prove beneficial to clinicians.

Validation of a simpler tool like the FOBS or a single question is required as there is a need for a tool that is easy and quick for women to fill in, as not all clinicians have time to administer the longer W-DEQ. Newly-developed, untested scales cannot easily be compared with other studies, and should not be used in clinical practice without further testing.

We recommend that future studies on FOC should use either the W-DEQ tool with a cut-off point of ≥85, or a more thoroughly tested version of either the FOBS scale with a higher cut-off point, or a single question such as ‘Are you afraid about the birth?’ with a three- or un-dichotimised four-point Likert response scale. In this way, valid comparisons can be made between countries and other studies.

Further research is also needed into reasons why FOC might differ in different countries and whether care for women with FOC needs to be made culturally specific. Measurement of FOC needs to include aspects such as fear of abandonment by staff during birth, fear of medical interventions, loss of autonomy and control, as well as fear of mistreatment and obstetrical violence. This more focused research agenda to guide future studies will result in more meaningful results that can be used to improve care provided for all women with fear of childbirth.

Abbreviations

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- FOBS:

-

Fear of birth scale

- FOC:

-

Fear of childbirth

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue scale

- W-DEQ:

-

The Wijma delivery expectancy/ experience questionnaire

References

Höjeberg P. Tröskelkvinnor: barnafödande som kultur [Threshold women: Childbirth as culture]. Carlsson: Stockholm; 2000.

Larkin P, Begley CM, Devane D. Women's experiences of labour and birth: an evolutionary concept analysis. Midwifery. 2009;25(2):e49–59.

Wijma K. Why focus on 'fear of childbirth'? J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2003;24(3):141–3.

Bewley S, Cockburn J. Responding to fear of childbirth. Lancet. 2002;359(9324):2128–9.

Storksen HT, Garthus-Niegel S, Adams SS, Vangen S, Eberhard-Gran M. Fear of childbirth and elective caesarean section: a population-based study. BMC Pregnancy childbirth. 2015;15:221.

Stützer PP, Berlit S, Lis S, Schmahl C, Sütterlin M, Tuschy B. Elective caesarean section on maternal request in Germany: factors affecting decision making concerning mode of delivery. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(5):1151–6.

Fuglenes D, Aas E, Botten G, Øian P, Kristiansen IS. Why do some pregnant women prefer cesarean? The influence of parity, delivery experiences, and fear. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(1):45. e41-45.e49

Handelzalts JE, Becker G, Ahren M-P, Lurie S, Raz N, Tamir Z, Sadan O. Personality, fear of childbirth and birth outcomes in nulliparous women. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(5):1055–62.

Marcé L-V: Traité de la folie des femmes enceintes, des nouvelles accouchées et des nourrices : et considérations médico-légales qui se rattachent à ce sujet / par le Dr L.-V. Marcé: J.-B. Baillière et fils (Paris); 1858.

Areskog B, Uddenberg N, Kjessler B. Fear of childbirth in late pregnancy. Gynecol Obstet Investig. 1981;12(5):262–6.

Saisto T, Halmesmaki E. Fear of childbirth: a neglected dilemma. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(3):201–8.

Hofberg K, Brockington I. Tokophobia: an unreasoning dread of childbirth. A series of 26 cases. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176(JAN):83–5.

Hofberg K, Ward MR. Fear of pregnancy and childbirth. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(935):505–10. quiz 508-510

Vogel JP, Betran AP, Vindevoghel N, Souza JP, Torloni MR, Zhang J, Tuncalp O, Mori R, Morisaki N, Ortiz-Panozo E, et al. Use of the Robson classification to assess caesarean section trends in 21 countries: a secondary analysis of two WHO multicountry surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(5):e260–70.

European perinatal health report: The health and care of pregnant women and babies in Europe in 2010. Paris: Euro Peristat European comission; 2013.

Ayers S. Fear of childbirth, postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder and midwifery care. Midwifery. 2014;30(2):145–8.

Haines HM, Rubertsson C, Pallant JF, Hildingsson I. The influence of women's fear, attitudes and beliefs of childbirth on mode and experience of birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:55.

Klabbers GA, JAvB H, MAvdH M, AJJM V. Severe fear of childbirth: its features, assesment, prevalence, determinants, consequences and possible treatments. Psychol Topics. 2016;25(1):107–27.

Alehagen S, Wijma B, Wijma K. Fear of childbirth before, during, and after childbirth. Acta Obstetricia & Gynecologica Scandinavica 2006;85:56–62.

Liljeroth P. Rädsla inför förlossningen : ett uppenbart kliniskt problem? Konstruktionen av förlossningsrädsla som medicinsk kategori [fear before delivery – an obvious clinical problem? The construction of fear of childbirth as a medical category]. Ekonomisk-statsvetenskapliga fakulteten vid Åbo Akademi: Åbo; 2009.

Walsh D. Birthwrite. Fear of labour and birth. Br J Midwifery. 2002;10(2):78.

Sampson M, McGowan J, Cogo E, Grimshaw J, Moher D, Lefebvre C. An evidence-based practice guideline for the peer review of electronic search strategies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(9):944–52.

EPHPP Quality Assessment tool for Quantitative Studies [http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html].

Garthus-Niegel S, von Soest T, Knoph C, Simonsen TB, Torgersen L, Eberhard-Gran M. The influence of women's preferences and actual mode of delivery on post-traumatic stress symptoms following childbirth: a population-based, longitudinal study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:191.

Garthus-Niegel S, von Soest T, Vollrath ME, Eberhard-Gran M. The impact of subjective birth experiences on post-traumatic stress symptoms: a longitudinal study. Archives Women's Mentl Health. 2013;16(1):1–10.

Hildingsson I, Rådestad I, Rubertsson C, Waldenström U. Few women wish to be delivered by caesarean section. BJOG: Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109(6):618–23.

Karlstrom A, Radestad I, Eriksson C, Rubertsson C, Nystedt A, Hildingsson I. Cesarean section without medical reason, 1997 to 2006: a Swedish register study. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2010;37(1):11–20.

Melender HL. Experiences of fears associated with pregnancy and childbirth: a study of 329 pregnant women. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2002;29(2):101–11.

Saisto T, Ylikorkala O, Halmesmaki E. Factors associated with fear of delivery in second pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(5 Pt 1):679–82.

Schwartz L, Toohill J, Creedy DK, Baird K, Gamble J, Fenwick J. Factors associated with childbirth self-efficacy in Australian childbearing women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):465.

Stjernholm YV, Petersson K, Eneroth E. Changed indications for cesarean sections. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89(1):49–53.

Takegata M, Haruna M, Matsuzaki M, Shiraishi M, Okano T, Severinsson E. Antenatal fear of childbirth and sense of coherence among healthy pregnant women in Japan: a cross-sectional study. Arch Women's Ment Health. 2014;17(5):403–9.

Nerum H, Halvorsen L, Sorlie T, Oian P. Maternal request for cesarean section due to fear of birth: can it be changed through crisis-oriented counseling? Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2006;33(3):221–8.

Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Gissler M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Mental health problems common in women with fear of childbirth. BJOG : Int J Bbstetrics Gynaecol. 2011;118(9):1104–11.

Ryding EL, Persson A, Onell C, Kvist L. An evaluation of midwives' counseling of pregnant women in fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(1):10–7.

Sjogren B. Fear of childbirth and psychosomatic support. A follow up of 72 women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1998;77(8):819–25.

Sjogren B, Thomassen P. Obstetric outcome in 100 women with severe anxiety over childbirth (structured abstract). Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:948–52.

Sydsjo G, Angerbjorn L, Palmquist S, Bladh M, Sydsjo A, Josefsson A. Secondary fear of childbirth prolongs the time to subsequent delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92(2):210–4.

Eriksson C, Jansson L, Hamberg K. Women's experiences of intense fear related to childbirth investigated in a Swedish qualitative study. Midwifery. 2006;22(3):240–8.

Faisal I, Matinnia N, Hejar AR, Khodakarami Z. Why do primigravidae request caesarean section in a normal pregnancy? A qualitative study in Iran. Midwifery. 2014;30(2):227–33.

Fenwick J, Staff L, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Bayes S. Why do women request caesarean section in a normal, healthy first pregnancy? Midwifery. 2010;26(4):394–400.

Fisher C, Hauck Y, Fenwick J. How social context impacts on women's fears of childbirth: a western Australian example. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(1):64–75.

Nilsson C, Bondas T, Lundgren I. Previous birth experience in women with intense fear of childbirth. J Obstet, Gynecol, Neonatal. 2010;39(3):298–309.

Nilsson C, Lundgren I. Women's lived experience of fear of childbirth. Midwifery. 2009;25(2):e1–9.

Ramvi E, Tangerud M. Experiences of women who have a vaginal birth after requesting a cesarean section due to a fear of birth: a biographical, narrative, interpretative study. Nursing Health Sci. 2011;13(3):269–74.

Ryding EL, Wijma K, Wijma B. Experiences of emergency cesarean section: a phenomenological study of 53 women. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 1998;25(4):246–51.

Salomonsson B, Bertero C, Alehagen S. Self-efficacy in pregnant women with severe fear of childbirth. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nursing. 2013;42(2):191–202.

Lyberg A, Severinsson E. Fear of childbirth: mothers' experiences of team-midwifery care - a follow-up study. J Nurs Manag. 2010;18(4):383–90.

Melender HL. Fears and coping strategies associated with pregnancy and childbirth in Finland. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2002;47(4):256–63.

Larsson B, Karlstrom A, Rubertsson C, Hildingsson I. The effects of counseling on fear of childbirth. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(6):629–66.

Hildingsson I, Nilsson C, Karlström A, Lundgren I. A longitudinal survey of childbirth-related fear and associated factors. J Obstet, Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(5):532–43.

Hildingsson I. Swedish couples' attitudes towards birth, childbirth fear and birth preferences and relation to mode of birth - a longitudinal cohort study. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2014;5(2):75–80.

Karlstrom A, Nystedt A, Johansson M, Hildingsson I. Behind the myth--few women prefer caesarean section in the absence of medical or obstetrical factors. Midwifery. 2011;27(5):620–7.

Karlstrom A, Nystedt A, Hildingsson I. A comparative study of the experience of childbirth between women who preferred and had a caesarean section and women who preferred and had a vaginal birth. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2011;2(3):93–9.

Hall WA, Stoll K, Hutton EK, Brown H. A prospective study of effects of psychological factors and sleep on obstetric interventions, mode of birth, and neonatal outcomes among low-risk British Columbian women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:78.

Stoll KH, Hall W. Childbirth education and obstetric interventions among low-risk canadian women: is there a connection? J Perinat Educ. 2012;21(4):229–37.

Laursen M, Johansen C, Hedegaard M. Fear of childbirth and risk for birth complications in nulliparous women in the Danish National Birth Cohort. BJOG : Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(10):1350–5.

Ryding EL, Lukasse M, Parys AS, Wangel AM, Karro H, Kristjansdottir H, Schroll AM, Schei B. Fear of childbirth and risk of cesarean delivery: a cohort study in six European countries. Birth (Berkeley, Calif). 2015;42(1):48–55.

Eriksson C, Westman G, Hamberg K. Content of childbirth-related fear in Swedish women and men - analysis of an open-ended question. J Midwifery Women's Health. 2006;51(2):112–8.

Hildingsson I, Thomas J, Karlström A, Olofsson RE, Nystedt A. Childbirth thoughts in mid-pregnancy: prevalence and associated factors in prospective parents. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2010;1(2):45–53.

Nilsson C, Lundgren I, Karlström A, Hildingsson I. Self reported fear of childbirth and its association with women's birth experience and mode of delivery: a longitudinal population-based study. Women Birth. 2012;25(3):114–21.

Lukasse M, Schei B, Ryding EL. Prevalence and associated factors of fear of childbirth in six European countries. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2014;5.

Elvander C, Cnattingius S, Kjerulff KH. Birth experience in women with low, intermediate or high levels of fear: findings from the first baby study. Birth: Issues Perinatal Care. 2013;40(4):289–96.

Laursen M, Hedegaard M, Johansen C. Fear of childbirth: predictors and temporal changes among nulliparous women in the Danish National Birth Cohort. BJOG. 2008;115(3):354–60.

Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Toivanen R, Tokola M, Halmesmaki E, Saisto T. Life satisfaction, general well-being and costs of treatment for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women by psychoeducative group or conventional care attendance. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica 2015;94(5):527–33.

Raisanen S, Lehto SM, Nielsen HS, Gissler M, Kramer MR, Heinonen S. Fear of childbirth in nulliparous and multiparous women: a population-based analysis of all singleton births in Finland in 1997-2010. BJOG. 2014;121(8):965–70.

Haines H, Pallant JF, Karlström A, Hildingsson I. Cross-cultural comparison of levels of childbirth-related fear in an Australian and Swedish sample. Midwifery. 2011;27(4):560–7.

Wijma K, Wijma B, Zar M. Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;19:84–97.

Geissbuehler V, Eberhard J. Fear of childbirth during pregnancy: a study of more than 8000 pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2002;23(4):229–35.

Waldenström U, Hildingsson I, Ryding EL. Antenatal fear of childbirth and its association with subsequent caesarean section and experience of childbirth. BJOG. 2006;113(6):638–46.

Eriksson C, Westman G, Hamberg K. Experiential factors associated with childbirth-related fear in Swedish women and men: a population based study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26(1):63–72.

Ternstrom E, Hildingsson I, Haines H, Rubertsson C: Higher prevalence of childbirth related fear in foreign born pregnant women - Findings from a community sample in Sweden. Midwifery 2014;31(4):445–40.

Fabian HM, Rådestad IJ, Waldenström U. Characteristics of Swedish women who do not attend childbirth and parenthood education classes during pregnancy. Midwifery. 2004;20(3):226–35.

Lowe NK. Self-efficacy for labor and childbirth fears in nulliparous pregnant women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;21(4):219–24.

Poikkeus P, Saisto T, Unkila-Kallio L, Punamaki RL, Repokari L, Vilska S, Tiitinen A, Tulppala M. Fear of childbirth and pregnancy-related anxiety in women conceiving with assisted reproduction. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(1):70–6.

Saisto T, Salmela-Aro K, Nurmi JE, Könönen T. E H: a randomized controlled trial of intervention in fear of childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(5):820–6.

Fenwick J, Gamble J, Nathan E, Bayes S, Hauck Y. Pre- and postpartum levels of childbirth fear and the relationship to birth outcomes in a cohort of Australian women. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(5):667–77.

Heimstad R, Dahloe R, Laache I, Skogvoll E, Schei B. Fear of childbirth and history of abuse: implications for pregnancy and delivery. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(4):435–40.

Nieminen K, Stephansson O, Ryding EL. Women's fear of childbirth and preference for cesarean section - a cross-sectional study at various stages of pregnancy in Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88(7):807–13.

Adams SS, Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A. Fear of childbirth and duration of labour: a study of 2206 women with intended vaginal delivery. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology. 2012;119:1238-46.

Jespersen C, Hegaard HK, Schroll A-M, Rosthøj S, Kjærgaard H. Fear of childbirth and emergency caesarean section in low-risk nulliparous women: a prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2014;35(4):109–15.

Jokić-Begić N, Žigić L, Radoš SN. Anxiety and anxiety sensitivity as predictors of fear of childbirth: different patterns for nulliparous and parous women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2014;35(1):22–8.

Soderquist J, Wijma K, Wijma B. Traumatic stress in late pregnancy. J Anxiety disord. 2004;18(2):127–42.

Zar M, Wijma K, Wijma B. Relations between anxiety disorders and fear of childbirth during late pregnancy. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2002;9(2):122–30.

Hall WA, Hauck YL, Carty EM, Hutton EK, Fenwick J, Stoll K. Childbirth fear, anxiety, fatigue, and sleep deprivation in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(5):567–76.

Rouhe H, Salmela-Aro K, Halmesmäki E, Saisto T. Fear of childbirth according to parity, gestational age, and obstetric history. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;116(1):67–73.

Haines HM, Pallant JF, Fenwick J, Gamble J, Creedy DK, Toohill J, Hildingsson I. Identifying women who are afraid of giving birth: a comparison of the fear of birth scale with the WDEQ-A in a large Australian cohort. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2015;6(4):204–10.

Johnson R, Slade P. Does fear of childbirth during pregnancy predict emergency caesarean section? BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109(11):1213–21.

Roosevelt L, Low LK. Exploring fear of childbirth in the United States through a qualitative assessment of the Wijma delivery expectancy questionnaire. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2016;45(1):28–38.

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, Aguiar C, Saraiva Coneglian F, Diniz ALA, Tunçalp Ö et al: The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review (The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth: A Systematic Review). 2015, 12(6):e1001847.

Nilvér H, Begley C, Berg M. Measuring women’s childbirth experiences: a systematic review for identification and analysis of validated instruments. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:203.

Stoll K, Hall W, Janssen P, Carty E. Why are young Canadians afraid of birth? A survey study of childbirth fear and birth preferences among Canadian University students. Midwifery. 2014;30(2):220–6.

Thomson G, Stoll K, Downe S, Hall WA. Negative impressions of childbirth in a north-West England student population. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(1):37–44.

Ayers S, Bond R, Bertullies S, Wijma K. The aetiology of post-traumatic stress following childbirth: a meta-analysis and theoretical framework. Psychol Med. 2016;46(6):1121–34.

Karabulut Ö, Coşkuner Potur D, Doğan Merih Y, Cebeci Mutlu S, Demirci N. Does antenatal education reduce fear of childbirth? Int Nurs Rev. 2016;63(1):60–7.

Serçekuş P, Başkale H. Effects of antenatal education on fear of childbirth, maternal self-efficacy and parental attachment. Midwifery. 2016;34:166–72.

Nieminen K, Andersson G, Wijma B, Ryding EL, Wijma K. Treatment of nulliparous women with severe fear of childbirth via the internet: a feasibility study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;37(2):37–43.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

There is no funding to report for this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the protocol. CN coordinated the review process. CS-L peer-reviewed the search strategy. CN developed the search string and conducted the searches with EH and HS. CN, AD, EJ, CS-L, MM, HP, HW, CB, independently selected papers for inclusion, assessed the quality of the included studies and extracted data. EH and HS documented the Prisma flow diagram. CB performed the data analysis. CB and AD made the Tables. CN wrote the background section. CB wrote the methodology and findings sections. All authors contributed to the discussion and read and commented on the manuscript during the writing process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

Not applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors CB and CS-L are members of the BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth Editorial Board.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (DOCX 96 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nilsson, C., Hessman, E., Sjöblom, H. et al. Definitions, measurements and prevalence of fear of childbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 28 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1659-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1659-7