Abstract

Background

Since 2010, intensive care can be offered in the Netherlands at 24+0 weeks gestation (with parental consent) but the Dutch guideline lacks recommendations on organization, content and preferred decision-making of the counselling. Our aim is to explore preferred prenatal counselling at the limits of viability by Dutch perinatal professionals and compare this to current care.

Methods

Online nationwide survey as part of the PreCo study (2013) amongst obstetricians and neonatologists in all Dutch level III perinatal care centers (n = 205).The survey regarded prenatal counselling at the limits of viability and focused on the domains of organization, content and decision-making in both current and preferred practice.

Results

One hundred twenty-two surveys were returned out of 205 eligible professionals (response rate 60%). Organization-wise: more than 80% of all professionals preferred (but currently missed) having protocols for several aspects of counselling, joint counselling by both neonatologist and obstetrician, and the use of supportive materials. Most professionals preferred using national or local data (70%) on outcome statistics for the counselling content, in contrast to the international statistics currently used (74%). Current decisions on initiation care were mostly made together (in 99% parents and doctor). This shared decision model was preferred by 95% of the professionals.

Conclusions

Dutch perinatal professionals would prefer more protocolized counselling, joint counselling, supportive material and local outcome statistics. Further studies on both barriers to perform adequate counselling, as well as on Dutch outcome statistics and parents’ opinions are needed in order to develop a national framework.

Trial registration

Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02782650, retrospectively registered May 2016.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The anticipated delivery of an extremely premature infant at the limits of viability confronts parents as well as perinatal professionals with medical, ethical and emotional issues; especially when a decision on the initiation of care has to be made. Since the first publication in 2002 by the American Academy of Pediatrics several (albeit different) guidelines and, recommendations and comments on periviability counselling have been published [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, there is no universally accepted way of performing prenatal counselling and, consequently, studies describe heterogeneous counselling practices worldwide [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Some guidelines on resuscitation at the limits of viability have included recommendations on the parental involvement in the decision-making process. However, both the extent of involvement of parents, as well as the range of gestational ages (GA) at which parents should be involved, varies between countries [8, 9, 11, 26].

In 2010, the Dutch guideline on perinatal practice in extremely premature delivery lowered the limit offering intensive care from 25+0 to 24+0 weeks GA. Just as some international guidelines which include a role for parents the Dutch guideline explicitly requires informed consent of parents when initiating intensive care at 24 weeks GA [27]. Although this guideline acknowledges the importance of prenatal counselling, recommendations on organization, content or decision-making of the counselling are very limited. A pilot-study exploring prenatal counselling in a simulated setting in a Dutch and American cohort (2010), showed heterogeneity in content and decision-making [28]. Although there are some recommendations on counselling [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], they may not be generally applicable in the Netherlands since cross-cultural differences in perinatal practices, healthcare organization, and physician and patient views are likely to exist [8, 9, 11, 26,27,28,29,30,31].

To compose a national framework on prenatal counselling at the limits of viability (currently 24 weeks GA in the Netherlands), the nationwide PreCo study (Prenatal Counselling in Prematurity) was designed, examining both professional and parental views. High quality of care originates when no differences exist between preferred and current counselling with uniformity between the involved caregivers (obstetricians and neonatologists) and specified to the needs of those receiving counselling [17, 21, 22].

The views of parents are at least as important as the view of the professionals in the topic of prenatal counselling at the limits of viability, and they will be studied separately. The primary aim of this study is to explore preferences amongst Dutch perinatal professionals on prenatal counselling at the limits of viability on three domains: organization, content, and decision-making-process. The secondary aim is to study differences between preferred and current counselling and between counselling preferences of neonatal and obstetrical professionals.

Methods

Study design

Cross-sectional study (PreCo survey) using an online survey.

Setting and study population

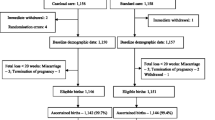

This study is part of the PreCo study, evaluating Dutch care in (imminent) extremely preterm birth including current and preferred counselling, barriers and facilitators for preferred counselling from both obstetrician and neonatologist, as well as parents’ views on this (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02782650 & NCT02782637). The results of the studies in parents are described [32] and will be described separately.

The care for extreme preterm births is centralized in the Netherlands in 10 level III centers for perinatal care which all participated in this study. Surveys were sent to all fellows and senior staff members in both obstetrics and neonatology. Data were collected from July 2012 through October 2013, approximately two to 3 years after the introduction of the new Dutch guideline on perinatal practice in extreme premature delivery.

Survey design and data collection

We developed the current survey in three stages just as described elsewhere. The first version was based on a combination of literature on prenatal counselling, several prenatal counselling surveys that were kindly shared with us [5, 16, 17, 33,34,35], observations from previous Dutch studies [28], and on public discussions generated by the Dutch guideline on perinatal practice in extreme premature delivery [27]. This survey was improved in two Delphi rounds containing both four team members and two independent professionals. The entire PreCo-survey required ~20 min to complete. The survey was adapted for both professional groups to exclude irrelevant questions and to optimize the participation rate.

The content of the PreCo survey included two topics on the care for children born at the limits of viability: prenatal counselling (preferred and current) and treatment decisions [36]. For this substudy we were interested in the first: both preferred and current prenatal counselling. We defined three domains of interest to investigate this: 1) organization 2) content and 3) the decision-making-process. We used a fictitious case of an ‘uncomplicated’ extreme premature delivery at 24 weeks to examine the three domains (textbox). The survey questions were designed to ask for both the preferred and current practice (Additional files 1 and 2).

Characteristics of the fictitious case | |

A consultation for prenatal counselling with an impending extreme premature delivery, singleton fetus, unremarkable history of pregnancy, average estimated fetal birth weight, unknown gender, no known congenital abnormalities, unremarkable social and medical history of parents, antenatal corticosteroids have been administered and normal fetal heart rate recording. |

An individual link to the online survey was sent to all participants. Three reminders were sent to non-responders. Survey results were anonymized before analysis. This study was exempt from IRB approval.

Data analysis

Summary statistics were given as proportions of the respondents for that specific question. To compare preferred counselling with current counselling McNemars Ӽ2, Bowker McNemars Ӽ2 or Wilcoxon-signed-rank test were used when applicable. For comparison of the counselling methods of obstetricians and neonatologists Ӽ2, Fisher exact test (F.ex) or Mann Whitney U test (MWU) were used when applicable. Exact p values were provided, values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

Results

Demographics

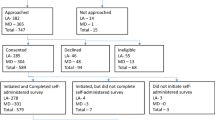

We received 122 surveys from 205 eligible perinatal professionalsFootnote 1; a response rate of 60%. Of those, 45 were from obstetricians and 77 from neonatologists. Each Dutch perinatal center was represented by at least five respondents. Of all 122 returned surveys, eight were partially completed. Obstetricians had fewer years of experience than neonatologists (Table 1).

Organization of prenatal counselling

With respect to the person who should conduct the counselling of the prospective parents, perinatal professionals (91%) preferred this done by the obstetrician and neonatologist jointly, but it occurred in 61% of current practice (Table 2).

Perinatal professionals would preferably like a protocol on several aspects of prenatal counselling (Table 3); who should be counselling (94%) and at which GA (98%), which topics should be discussed (85%), and the GA at which intensive care can be offered (98%) and comfort care accepted (84%). In current practice, some of these aspects were already put into protocols.

Neonatologists wanted to use more supporting material in their consultation (p < 0.01); either written (93%) or online (65%) information or a decision-aid (DA) (42%). This was different from the current situation where only 38% of the neonatologists used written information. Other modalities were used less (website 7%, video 3%, DA 1%, other 7%).

Starting at 24+0/7 weeks of GA, obstetricians preferred to ask the neonatologist often or always (98%) to provide counselling to parents in imminent preterm delivery (Fig. 1). At 22 weeks of GA, neonatologists should never or rarely be asked according to 86% of the obstetricians. At 23 weeks of GA, there was no consensus.

Of the neonatologists, 58% preferred to have more than one prenatal counselling meeting with the parents, significantly different from current practice (only 18% had more than one meeting) (p < 0.01). Preferably counselling should take between 15 and 45 min, comparable with current practice. The content of the consultation should be documented in both the mother’s and the infant’s medical record (76%) which was different from the current situation where it was documented only in the mother’s file (58%) (p < 0.01).

Content of prenatal counselling

An overview of topics (from a predefined list) that neonatologists think should be discussed during prenatal counselling is given in order of frequency in Table 4. The most important topics were: mortality, morbidity, intubation/ventilation and intraventricular hemorrhage.

When providing outcome statistics, perinatal professionals preferred to use national (48%) or hospital-specific (22%) outcome statistics. Only 21% preferred international data, which was used by the majority in current practice (74%) (p < 0.01). Not every neonatologist did provide outcome statistics in current practice: the ‘mortality rate for the unborn fetus’ was provided by 38%, the ‘mortality rate for live-born infants’ was provided by 66% and the ‘survival rate without severe disabilities’ was provided by 76%. When providing prognostic statistics, there was a wide range in the used percentages by neonatologists (Fig. 2).

Decision-making in prenatal counselling

The decision to initiate intensive care treatment should, according to perinatal professionals, preferably be made using the shared decision making (SDM) model 95% strongly agreed (Fig. 3). There was less preference for the other models, of all perinatal professionals 27% agreed with the informed and 13% with the paternalistic model as preferred decision-model. There was a significant disagreement within the informed model; obstetricians mainly agreed and neonatologists mainly disagreed with this model.

Preferred decision-making-model at 24 weeks GA on inititating intensive treatment at birth or not. Answer options: •The decision to initiate intensive treatment at birth should only be made by a health care professional (paternalistic model). •The decision to initiate intensive treatment at birth should be made by the parents, after prenatal counselling (informed model). •The decision to initiate intensive treatment at birth should be made by the health care professional and parents together (shared-decision model)

Current decisions were mostly made by the parents and doctor together (99%). Of those decisions, 28% stated that the professional opinion is decisive, 24% said parents and professional were equally decisive and for 47% the parental opinion was decisive. In these, there were no differences between obstetricians and neonatologists.

Other

Six potential indicators of high quality of prenatal counselling were rated. In order of importance, the indicator health care professional and parents take the decision together equally (shared-decision making) scored highest (86% of the participants thought this was a fairly good or very good indicator), followed by when the parents are very satisfied with the consultation (78% fairly good or very good) and when the content and percentages are medically accurate (68% fairly good or very good). Lower scores were found for when the health care professional is very satisfied with the consultation (44% fairly good or very good), when all possible complications of premature delivery are discussed (37% fairly good or very good) and the length of the consultation – the longer, the better/more accurate (4% fairly good or very good).

Discussion

This nationwide study on prenatal counselling includes both obstetricians and neonatologists from all level III perinatal care centers. In the domain of organization, perinatal professionals preferred joint counselling by both the obstetrician and neonatologist, protocols for several aspects of prenatal counselling, supportive material, and the neonatologist to join counselling starting at 23-24 weeks GA. In the domain of content, the most important topics to discuss were: mortality, morbidity, intubation/ventilation and intraventricular hemorrhage. Perinatal professionals wanted national or hospital based outcome statistics. In the domain of decision-making, perinatal professionals preferred the SDM-model to decide whether or not to initiate treatment. Results of this study can be used when developing a national framework, combined with the results from parental preferences and qualitative explorations.

Organization of prenatal counselling

Prenatal counselling done together by the neonatologist and obstetrician was preferred just as recommended internationally [1, 2]. Further qualitative research is required to study why this is not usually done in current care, but a hypothesis is that caregivers are simply not simultaneously available at all hours of the day.

The content of the consultation should be documented in both mother’s and infant’s file instead of just in the mother’s file. It is known that records of antenatal consultations were often lacking important information [37]. A technical barrier might be the absence of a medical record for an unborn baby.

A preference for more guidance of prenatal counselling at the limits of viability was reported. In other countries several guidelines and recommendations have been suggested to support professionals performing this difficult task [1,2,3, 6, 11]. However, disadvantages were mentioned by Janvier [38], who advocates for an approach where doctors should personalize their information and distinguish what specific information parents need. An individual approach and a guideline might not necessarily conflict: a framework on certain aspects of counselling can be of additional value without standardizing prenatal counselling sessions, especially when it’s not too rigid and incorporates solutions to help professionals personalizing the counselling.

Dutch neonatologists wanted to use more supportive material. Grobman found that 60% of parents asked for written material, in contrast to 15% of the physicians who were concerned that clinical conditions could change so rapidly that static resources would not be effective [19]. In 2012, Muthusamy showed in a randomized controlled trial that supplementation of face-to-face verbal counselling with written information improved knowledge and decreased anxiety in women expecting a premature delivery [39]. Guillen and Kakkilaya suggest benefit by the use of a DA [40, 41].

Currently, at a nonviable GA the neonatologist was not considered to take part in counselling in the Netherlands. This in contrast to e.g. California (survey from 1996) and the Pacific Rim (survey from 1999 to 2000) in which at 22 and 23 weeks GA neonatologists were asked to counsel parents [14, 42] The presence of a neonatologist might be helpful, even to explain the rationale of non-active management and to offer comfort care in live-born, immature infants, although a barrier is present since only neonatologists in tertiary centers are trained to counsel these parents.

Content of prenatal counselling

Many topics were considered important to discuss. However, time might be limited due to an impending delivery and parents will not remember everything when overloaded with information [43]. Therefore, parents’ view on which content should be discussed is essential. From a caregivers perspective, a vast majority preferred to discuss two of the major disabilities (motor and cognitive impairment), but the other two major disabilities (blindness and deafness) were considered less important. We hypothesize that this might be explained by the higher incidence of impaired mental development and cerebral palsy compared to blindness and deafness [44].

Variable morbidity and mortality rates were communicated in prenatal counselling. It is difficult to pinpoint the correct percentages for the Dutch situation since during this survey no Dutch outcome data were available, and international statistics vary. A considerable number of neonatologists did not even mention prognostic statistics. Statistics may not always be of additional value to parents. Boss found that physicians’ predictions of morbidity and death are not central to parental decision-making regarding delivery room resuscitation [33]. Janvier rightly appoints the disadvantages of using statistics, i.e. that percentages might not be understood, that its interpretation is framing-dependent and that percentages do not predict the outcome for the individual baby [38]. Nevertheless, Partridge found that “more data on outcomes” was recommended for NICU counselling by parents, suggesting that parents want to be informed about prognostic statistics [35].

Decision-making in prenatal counselling

SDM was the preferred decision-model at the threshold of viability, which is consistent with other studies [2, 4, 11, 34, 35, 45]. Although in current prenatal counselling 99% of the decisions are made by doctor and parent together, 28% of the caregivers state that their decision is decisive. It is likely that caregivers might not be fully aware of the way they perform both their current counselling nor that they understand what SDM actually means. SDM is defined as clinicians and patients making decisions together using the best available evidence. This definition states that patients are encouraged to think along and benefits and harms are discussed together [46]. For the implementation of SDM, ready access to evidence based information about treatment options must be met, as well as guidance on how to weigh up the pros and cons of different options and a supportive clinical culture that facilitates patient engagement. Although neonatologists agreed that a DA could be helpful, earlier studies suggested a paternalistic approach [28] and even in this current survey, some of the participants did endorse the informed and/or paternalistic model as well as SDM.

Other

Participants regarded the implementation of SDM a good indicator for a high quality consultation. Furthermore, they thought an important indicator is when parents were very satisfied with the consultation – more important than the satisfaction of the professional. Therefore it is of utmost importance to reveal the preferences of parents in the prenatal counselling. Especially since it is known that views of professionals and parents might differ [47, 48]. Input of professionals and parents should be used for the development of (local) recommendations for prenatal counselling in extreme prematurity.

Strengths and limitations

The strongest aspect of this study is its nationwide character, together with an adequate response rate. Part of the survey was directly related to content of the Dutch guideline on perinatal practice, making it relevant for daily practice. This guideline recommends counselling but without giving tools to do so. Our nationwide PreCo study has been set up to examine this counselling, starting with this first exploration of preferred and current counselling.

The limitation of the survey methodology is a potential discrepancy between answers given and actual practice. Besides, direct observations of the counselling conversations could potentially reveal other strengths and weaknesses than we have questioned in this survey, especially interpersonal communication is not easily highlighted in a survey. Due to the inclusion period, effects of experience or learning cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, these Dutch results may not be generalized to an international population. However, both guidelines and a ‘gray zone of viability’ exist worldwide, and although these are not exactly similar to the Dutch counterpart, general conclusions might be applicable.

Conclusion

This first study on prenatal counselling in the Netherlands revealed differences between preferred and current counselling, and between obstetricians and neonatologists, suggesting a potential for improvement. Further studies looking into the barriers of preferred prenatal counselling [49] could be used to make improvements. Also, preferences of parents will be investigated.

Variation in prenatal counselling is in the best interest of the patient when due to individual (maternal or fetal) characteristics or parental beliefs. When, however, variation is due to unclear background information, insufficient organizational support or incorrect personal habits of healthcare providers, it is not in the best interest of the patient. The use of a nationally developed and supported framework might improve quality of prenatal consultation and even give more scope for individualization.

Change history

19 February 2018

Following publication of the original article [1], the corresponding authors wrote to say that there was a mistake in the transfer of her article to PubMed: her name is R Geurtzen, but the pdf-file names her as ms R Geurtzen and pubmed names her as MR Geurtzen.

Notes

When in this manuscript the perinatal professionals were mentioned: both obstetricians and neonatologists are meant. Since some in-depth questions were asked only to one of the disciplines, we then noted the applicable discipline (either neonatologists or obstetricians)

Abbreviations

- DA:

-

decision-aid

- F.ex:

-

Fisher exact test,

- GA:

-

gestational age

- MWU:

-

Mann Whitney U test

- SDM:

-

shared-decision-making,

References

Batton DG, Committee on F, newborn. Clinical report--antenatal counseling regarding resuscitation at an extremely low gestational age. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):422–7.

Griswold KJ, Fanaroff JM. An evidence-based overview of prenatal consultation with a focus on infants born at the limits of viability. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):e931–7.

Jefferies AL, Kirpalani HM, Canadian Paediatric society F, newborn C. Counselling and management for anticipated extremely preterm birth. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17(8):443–6.

Janvier A, Barrington KJ, Aziz K, Bancalari E, Batton D, Bellieni C, Bensouda B, Blanco C, Cheung PY, Cohn F, et al. CPS position statement for prenatal counselling before a premature birth: simple rules for complicated decisions. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(1):22–4.

Kaempf JW, Tomlinson M, Arduza C, Anderson S, Campbell B, Ferguson LA, Zabari M, Stewart VT. Medical staff guidelines for periviability pregnancy counseling and medical treatment of extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):22–9.

Kaempf JW, Tomlinson MW, Campbell B, Ferguson L, Stewart VT. Counseling pregnant women who may deliver extremely premature infants: medical care guidelines, family choices, and neonatal outcomes. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1509–15.

Raju TN, Mercer BM, Burchfield DJ, Joseph GF Jr. Periviable birth: executive summary of a joint workshop by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):1083–96.

Gallagher K, Martin J, Keller M, Marlow N. European variation in decision-making and parental involvement during preterm birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99(3):F245–9.

Pignotti MS, Donzelli G. Perinatal care at the threshold of viability: an international comparison of practical guidelines for the treatment of extremely preterm births. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):e193–8.

MacDonald H, American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on F, Newborn. Perinatal care at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):1024–7.

Cummings J, Committee On F, Newborn. Antenatal counseling regarding resuscitation and intensive care before 25 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2015;136(3):588–95.

Guillen U, Weiss EM, Munson D, Maton P, Jefferies A, Norman M, Naulaers G, Mendes J, Justo da Silva L, Zoban P, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Extremely Premature Deliveries: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):343–50.

Ohlinger J, Kantak A, Lavin JP Jr, Fofah O, Hagen E, Suresh G, Halamek LP, Schriefer JA. Evaluation and development of potentially better practices for perinatal and neonatal communication and collaboration. Pediatrics. 2006;118(Suppl 2):S147–52.

Martinez AM, Partridge JC, Yu V, Wee Tan K, Yeung CY, JH L, Nishida H, Boo NY. Physician counselling practices and decision-making for extremely preterm infants in the Pacific Rim. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41(4):209–14.

Mulvey S, Partridge JC, Martinez AM, VY Y, Wallace EM. The management of extremely premature infants and the perceptions of viability and parental counselling practices of Australian obstetricians. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;41(3):269–73.

Bastek TK, Richardson DK, Zupancic JA, Burns JP. Prenatal consultation practices at the border of viability: a regional survey. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):407–13.

Chan KL, Kean LH, Marlow N. Staff views on the management of the extremely preterm infant. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;128(1-2):142–7.

Govande VP, Brasel KJ, Das UG, Koop JI, Lagatta J, Basir MA. Prenatal counseling beyond the threshold of viability. J Perinatol. 2013;33(5):358–62.

Grobman WA, Kavanaugh K, Moro T, DeRegnier RA, Savage T. Providing advice to parents for women at acutely high risk of periviable delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(5):904–9.

Mehrotra A, Lagatta J, Simpson P, Kim UO, Nugent M, Basir MA. Variations among US hospitals in counseling practices regarding prematurely born infants. J Perinatol. 2013;33(7):509–13.

Taittonen L, Korhonen P, Palomaki O, Luukkaala T, Tammela O. Opinions on the counselling, care and outcome of extremely premature birth among healthcare professionals in Finland. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103(3):262–7.

Duffy D, Reynolds P. Babies born at the threshold of viability: attitudes of paediatric consultants and trainees in south East England. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(1):42–6.

Tucker Edmonds B, McKenzie F, Panoch JE, Barnato AE, Frankel RM. Comparing obstetricians' and neonatologists' approaches to periviable counseling. J Perinatol. 2015;35(5):344–8.

Keenan HT, Doron MW, Seyda BA. Comparison of mothers' and counselors' perceptions of predelivery counseling for extremely premature infants. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):104–11.

Tucker Edmonds B, Krasny S, Srinivas S, Shea J. Obstetric decision-making and counseling at the limits of viability. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(3):248 e241-245.

Brunkhorst J, Weiner J, Lantos J. Infants of borderline viability: the ethics of delivery room care. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;19(5):290–5.

de Laat MW, Wiegerinck MM, Walther FJ, Boluyt N, Mol BW, van der Post JA, van Lith JM, Offringa M, Nederlandse Vereniging voor K, Nederlandse Vereniging voor Obstetrie en G. Practice guideline 'Perinatal management of extremely preterm delivery'. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2010;154:A2701.

Geurtzen R, Hogeveen M, Rajani AK, Chitkara R, Antonius T, van Heijst A, Draaisma J, Halamek LP. Using simulation to study difficult clinical issues: prenatal counseling at the threshold of viability across American and Dutch cultures. Simul Healthc. 2014;9(3):167–73.

Cuttini M. Neonatal intensive care and parental participation in decision making. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84(1):F78.

Lorenz JM, Paneth N, Jetton JR, den Ouden L, Tyson JE. Comparison of management strategies for extreme prematurity in New Jersey and the Netherlands: outcomes and resource expenditure. Pediatrics. 2001;108(6):1269–74.

Lantos JD. International and cross-cultural dimensions of treatment decisions for neonates. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20(5):368–72.

Geurtzen R, Draaisma J, Hermens R, Scheepers H, Woiski M, van Heijst A, et al. Prenatal (non) treatment decisions in extreme prematurity: evaluation of decisional conflict and regret among parents. J Perinatol. 2017;37(9):999-1002.

Geurtzen R, Draaisma J, Hermens R, Scheepers H, Woiski M, van Heijst A, Hogeveen M. Perinatal practice in extreme premature delivery: variation in Dutch physicians' preferences despite guideline. Eur J Pediatr. 2016;175(8):1039–46.

Kavanaugh K, Savage T, Kilpatrick S, Kimura R, Hershberger P. Life support decisions for extremely premature infants: report of a pilot study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(5):347–59.

Partridge JC, Martinez AM, Nishida H, Boo NY, Tan KW, Yeung CY, JH L, VY Y. International comparison of care for very low birth weight infants: parents' perceptions of counseling and decision-making. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):e263–71.

Boss RD, Hutton N, Sulpar LJ, West AM, Donohue PK. Values parents apply to decision-making regarding delivery room resuscitation for high-risk newborns. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):583–9.

Janvier A, Barrington KJ. The ethics of neonatal resuscitation at the margins of viability: informed consent and outcomes. J Pediatr. 2005;147(5):579–85.

Janvier A, Lorenz JM, Lantos JD. Antenatal counselling for parents facing an extremely preterm birth: limitations of the medical evidence. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101(8):800–4.

Muthusamy AD, Leuthner S, Gaebler-Uhing C, Hoffmann RG, Li SH, Basir MA. Supplemental written information improves prenatal counseling: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129(5):e1269–74.

Guillen U, Suh S, Munson D, Posencheg M, Truitt E, Zupancic JA, Gafni A, Kirpalani H. Development and pretesting of a decision-aid to use when counseling parents facing imminent extreme premature delivery. J Pediatr. 2012;160(3):382–7.

Kakkilaya V, Groome LJ, Platt D, Kurepa D, Pramanik A, Caldito G, Conrad L, Bocchini JA, Jr., Davis TC: Use of a visual aid to improve counseling at the threshold of viability. Pediatrics 2011, 128(6):e1511-e1519.

Partridge JC, Freeman H, Weiss E, Martinez AM. Delivery room resuscitation decisions for extremely low birthweight infants in California. J Perinatol. 2001;21(1):27–33.

Kessels RP. Patients' memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(5):219–22.

Lorenz JM. The outcome of extreme prematurity. Semin Perinatol. 2001;25(5):348–59.

Haward MF, Kirshenbaum NW, Campbell DE. Care at the edge of viability: medical and ethical issues. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(3):471–92.

Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146.

Roscigno CI, Savage TA, Kavanaugh K, Moro TT, Kilpatrick SJ, Strassner HT, Grobman WA, Kimura RE. Divergent views of hope influencing communications between parents and hospital providers. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(9):1232–46.

Zupancic JA, Kirpalani H, Barrett J, Stewart S, Gafni A, Streiner D, Beecroft ML, Smith P. Characterising doctor-parent communication in counselling for impending preterm delivery. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87(2):F113–7.

Geurtzen R, van Heijst A, Draaisma J, Ouwerkerk L, Scheepers H, Woiski M, Hermens R, Hogeveen M. Professionals' preferences in prenatal counseling at the limits of viability: a nationwide qualitative Dutch study. Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(8):1107–19.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating Dutch obstetricians and neonatologists. Also, the authors would like to thank all authors who shared their survey with us [5, 16, 17, 33,34,35].

Funding

No external funding for this manuscript. All authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset of this article is available upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RG conceptualized the study, designed the survey, carried out the data collection and initial analysis, interpreted the results, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AvH and JD conceptualized the study, helped designing the survey, interpreted the results, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. RH and MW helped designing the survey, interpreted the results, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. HS interpreted the results, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MH conceptualized the study, helped designing the survey, supervised data collection and analysis, interpreted the results, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was exempt from IRB approval because of the survey-methodology examining only professionals, this was confirmed by the IRB (CMO region Arnhem – Nijmegen, file number 2015-1998).

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional information

The original version of this article was revised: The corresponding author asked for her name to be changed to R. Geurtzen.

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-018-1680-x.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Survey neonatologists. Survey presented to the neonatologists, translated from Dutch to English. Note: The actual survey was sent out online, with a different lay-out. (PDF 239 kb)

Additional file 2:

Survey obstetricians. Survey presented to the obstetricians, translated from Dutch to English. Note: The actual survey was sent out online, with a different lay-out. (PDF 232 kb)

Rights and permissions

, corrected publication February/2018. Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Geurtzen, R., Van Heijst, A., Hermens, R. et al. Preferred prenatal counselling at the limits of viability: a survey among Dutch perinatal professionals. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 18, 7 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1644-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-017-1644-6