Abstract

Background

Hereditary spastic paraplegia is a large group of degenerative, neurological disorders characterized by progressive lower limb spasticity and weakness. The disease was investigated precisely but still clinicians often make incorrect or late diagnosis. Our aim was to investigate the genetic background and clinical phenotype of spastic paraplegia in large Polish family.

Case presentation

A 37 years old woman presented with 4-year history of walking difficulties. On neurological examination, she had signs of upper motor lesion in lower extremities. She denied sphincter dysfunction and her cognition was normal. Her family history was positive for individuals with gait problems. The initial diagnosis was familial spastic paraplegia. Genetic testing identified a novel mutation in SPAST gene. All available family members were examined and had genetic testing. The same mutation in SPAST gene was identified in other affected family members. All patients caring the mutation presented with different phenotypes.

Conclusion

This study presents a family with spastic paraplegia due to a novel mutation c.1390G›T(p.Glu464Term) in SPAST gene. Affected individuals showed a range of phenotypes that varied in their severity. This case report demonstrates, the signs of hereditary spastic paraplegia can be often misdiagnosed with other diseases. Therefore genetic testing should always be considered in patients with lower limb spasticity and positive family history in order to help to establish the correct diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) are a rare and heterogeneous group of neurodegenerative disorders characterized by slowly progressive spasticity and weakness of lower extremities. Its prevalence varies from 1.2 to 9.6/100000 [1].

HSPs are classified by the phenotype, the trait of inheritance and the mutated gene. Based on the phenotype, HSPs are classified as pure when spastic paraplegia is the only symptom or complex when it is associated with other clinical features like involvement of upper extremities, cognitive impairment and behavioral changes.

The most commonly involved are SPAST and ATL1 genes. Mutations in the SPAST on chromosome 2p22.3 account for 15–40% of all autosomal dominant HSPs cases [2]. It encodes the protein spastin, a member of the ATPase associated with diverse cellular activity family with a role in microtubule dynamics.

Clinically, HSPs due to mutations in SPAST, present as a pure form in most cases but phenotypic variations are also reported [3].

Strategy for exploration of gene of interest is guided by clinical presentation, model of inheritance, and age of onset. In our case, the pure clinical form, autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, and age of onset above 20 years led us to begin with exploring SPAST gene. Genetic studies identified a new mutation in AAA-domain of SPAST gene. To confirm the pathogenicity of this mutation we used computational predictive programs and additionally we assessed co-segregation in affected family members. Those who had signs of upper motor lesion and had been previously diagnosed with other diseases, carried the same mutation.

Case presentation

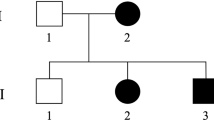

A 37 years old woman (E) presented with walking difficulties. The first symptoms began 4 years prior to presentation when she noticed walking more slowly. She had no other complaints, denied previous and current use of drugs. Some other members of her family also experienced gait problems. (Fig. 1 presents the pedigree of the family. Table 1. presents characteristics of family members.)

Pedigree of a family with spastic paraplegia. Black circles (females) and squares (males) represent affected people with spastic paraplegia. Cross-hatched symbols represents affected individuals already deceased (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). Unaffected individuals are not shaded. Individuals A,B,C, D, E, F, G, H had neurological and genetic evaluations

On neurological examination, she had spastic gait, symmetrical proximal weakness of the lower extremities (quadriceps and gluteal muscle), mild spasticity in hamstrings, quadriceps, adductors, gastrocnemius, and soleus. Increased deep tendon reflexes and Babinski sign were present bilaterally. She denied sphincter dysfunction. Her cognition was normal.

Laboratory tests did not reveal any abnormalities in blood count, electrolytes value, coagulation test, renal, hepatic or thyroid functions. C-reactive protein was ‹ 1 mg/L. Vitamin B12 level was normal. The nerve conduction study and evoked visual potentials were normal. Spinal and brain MR showed normal appearance of corpus callosum and did not find any cause of pyramidal syndrome. She was diagnosed with progressive pyramidal syndrome exclusively involving lower extremities. Her initial diagnosis was HSP.

After a written consent was obtained from the patient, the blood was taken for genetic testing. Molecular DNA analysis of the SPAST gene was performed. The Sanger sequencing method revealed mutation in one allele of SPAST gene: c.1390G›T(p.Glu464Term). This variant was not registered in the following genetic public database: HGMD, LOVD, NCBI ClinVar, dbSNP and ExAC. To determine pathogenicity in silico of this variant we used online prediction programs: Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/), SIFT/Provean (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php), PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/index.shtml). Also, the blood samples for DNA testing were collected from 7 other available family members. The work was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The same mutation was identified in 3 other probands (A,F,G). The pathogenicity of the novel mutation found in this study was categorized according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics [4]. Under this criteria this mutation was classified as pathogenic (Criteria: PVS1, PM1, PM2, PM4).

Patient (A), 56 years old woman, did not complain of any neurological symptoms or gait difficulties but presented with brisk reflexes and bilateral Babinski sign on neurological examination.

Patient F, 57 years old woman, suffered from polio disease when he was 8, with right hemiparesis and full recovery after a few months. At the age of 37, he experienced increasing walking difficulties. He was diagnosed with post-polio syndrome. At the age of 39 he was unable to work as a carpenter.

On neurological examination, he had spastic gait with heel strike progressively shifted forward, and asymmetrical proximal weakness of the lower extremities, more advanced on the right one. Severe spasticity in quadriceps, hamstrings, thigh adductor muscles, gastrocnemius and soleus was also found. Increased deep tendon reflexes in lower limbs and Babinski sign were present bilaterally. He denied sphincter dysfunction. His cognition was normal.

Another family member (G), 51 years old man, started to experience problems in her late thirties. She was admitted to the hospital in 2007. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis and laboratory tests did not reveal any abnormalities. The nerve conduction study was normal. The cervical and thoracic MR shoved disc herniation with suspicion of spinal cord suppression on multiple levels. Patient was discharged from the hospital with diagnosis of lower limb spasticity due to disc herniation: Th6/Th7 and Th8/TH9 and qualified for neurosurgery. Before agreeing to the surgery she sought neurosurgery consultation in another clinic. She had another thoracic spine MR, confirming multilevel disc herniation, but the signal of the spine was not changed, therefore she was disqualified from operation. Since that time, she observed slow progression of disability despite constant rehabilitation.

On neurological examination, she had spastic gait, symmetrical weakness of the lower limbs, mild spasticity in hamstrings, quadriceps, adductors, gastrocnemius, and soleus. Increased deep tendon reflexes in lower limbs and Babinski sign were present bilaterally. She did not report any sphincter dysfunction. Her cognition was normal.

The other genotyped family members (B,C,D,H) had no clinical and neurological symptoms and signs, and did not carry the mutation.

Our observational study indicates that novel variant c.1390G›T(p.Glu464Term) in SPAST gene is associated with HSP.

Patient has provided informed consent for publication of the case.

Discussion and conclusions

The novel mutation was identified in the AAA-domain of SPAST, region where most identified so far variants were located and still new studies confirm this observation [5].

As described before, the clinical expression of mutations in SPAST gene within a family may vary from asymptomatic patients, mildly affected individuals to severely affected patients [3]. Our study confirms this observation; the phenotype of affected family members varied from absence of clinical symptoms and complains to severe disability. The onset of symptoms was above 30 years of age in all cases, there was no association with sex and affected parent age at onset, what is consistent with previous studies [6].

To summarize, our study presents a family with a novel mutation in SPAST gene. The affected family members presented with different clinical phenotypes. The medical history of affected subjects shoves that clinical symptoms characteristic for HSP can be misdiagnosed with other diseases. Therefor in patients with spastic paraparesis and positive family history for gait problems, the HSP should be suspected at the top of differential diagnosis list and genetic testing should be considered.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- HSP:

-

Hereditary spastic paraplegia

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

References

Finsterer J, Löscher W, Quasthoff S, Wanschitz J, Auer-Grumbach M. Hereditary spastic paraplegias with autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, or maternal trait of inheritance. J Neurol Sci. 2012;318:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2012.03.025.

Solowska JM, Baas PW. Hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG4: what is known and not known about the disease. Brain. 2015;138:2471–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv178.

Orlacchio A, Patrono C, Borreca A, Babalini C, Bernardi G, Kawari T. Spastic paraplegia in Romania: high prevalence of SPG4 mutations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:606–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.128827.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL, ACMG laboratory quality assurance committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the association for molecular pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2015.30 Epub 2015 Mar 5.

Kadnikova VA, Rudenskaya GE, Stepanova AA, Sermyagina IG, Ryzhkova OP. Mutational Spectrum of Spast (Spg4) and Atl1 (Spg3a) genes in Russian patients with hereditary spastic paraplegia. Sci Rep. 2019;8:14412. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50911-9.

Coutinho P, Ruano L, Loureiro JL, Cruz VT, Barros J, Tuna A, Barbot C, Guimarães J, Alonso I, Silveira I, Sequeiros J, Marques Neves J, Serrano P, Silva MC. hereditary ataxia and spastic paraplegia in Portugal: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:746–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.1707.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AKM: conception and design of study, execution, drafting the article, revising the article, final approval of submitted version. AD execution, final approval of submitted version. MS execution, final approval of submitted version. MK execution, final approval of submitted version. AG: revising the article, final approval of submitted version. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written consent was obtained from all study participants patients for genetic testing.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and all other family members, for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copies of the written consents are available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Klimkowicz-Mrowiec, A., Dziubek, A., Sado, M. et al. Case report on novel mutation in SPAST gene in Polish family with spastic paraplegia. BMC Neurol 19, 322 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1561-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-019-1561-6