Abstract

Background

Fever after stroke is common, and often caused by infections. In the current study, we aimed to test the hypothesis that pneumonia, urinary tract infection and all-cause fever (thought to include at least some proportion of endogenous fever) have different predicting factors, since they differ regarding etiology.

Methods

PubMed was searched systematically for articles describing predictors for post-stroke pneumonia, urinary tract infection and all-cause fever. A total of 5294 articles were manually assessed; first by title, then by abstract and finally by full text. Data was extracted from each study, and for variables reported in 3 or more articles, a meta-analysis was performed using a random effects model.

Results

Fifty-nine articles met the inclusion criteria. It was found that post-stroke pneumonia is predicted by age OR 1.07 (1.04–1.11), male sex OR 1.42 (1.17–1.74), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) OR 1.07 (1.05–1.09), dysphagia OR 3.53 (2.69–4.64), nasogastric tube OR 5.29 (3.01–9.32), diabetes OR 1.15 (1.08–1.23), mechanical ventilation OR 4.65 (2.50–8.65), smoking OR 1.16 (1.08–1.26), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) OR 4.48 (1.82–11.00) and atrial fibrillation OR 1.37 (1.22–1.55). An opposite relation to sex may exist for UTI, which seems to be more common in women.

Conclusions

The lack of studies simultaneously studying a wide range of predictors for UTI or all-cause fever calls for future research in this area. The importance of new research would be to improve our understanding of fever complications to facilitate greater vigilance, monitoring, prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infections after stroke are common, and the prevalence has been reported to be as high as 30%; one third consisting of pneumonia and another third of urinary tract infections (UTI) [1]. These infections are associated with higher morbidity and mortality [2]. However, fever after stroke can also be endogenous, commonly referred to as “central fever”, caused by immune system activation or effects of the brain lesion on thermoregulatory centers, and such episodes are often difficult to distinguish from infections [3]. Central fever has not been very well characterized, but is probably resistant to antibiotic treatment and antipyretic treatment and probably appears early after stroke [3]. Fever without an identified infection has been reported to occur in 14.8% of stroke patients [3], but this number is uncertain, and reasonably depends on how thoroughly the patients have been investigated for focal signs of infections. Regardless of the causes, elevated body temperature after stroke is associated with poor prognosis [4, 5].

By understanding the risk factors of different types of infections and fever, risk profiles of specific patients could be assessed, in turn facilitating the diagnostics in stroke patients with increased body temperature. A meta-analysis comparing risk factors for different fever-related complications is lacking. In this study it was hypothesized that pneumonia, urinary tract infection (UTI) and all-cause fever have different predictors, since they differ regarding etiology. Therefore the aim of this study was to perform a meta-analysis to compare the predictors for post-stroke pneumonia, UTI and all-cause fever.

Methods

Literature search

PubMed was searched through its inception to September 16th, 2016 by using the MeSH terms “Cerebral Infarction”, “Stroke”, “Cerebral Hemorrhage” and the free text terms “fever”, “infection”, “pneumonia” and “urinary tract infection”. The search was complemented by a free text search using the same terms and filtered for “Ahead of print” to catch studies which were not found in the MeSH term search. Two more searches was performed; 1) using MeSH terms “Stroke/complications”, “Stroke/epidemiology”, “Stroke/physiology”, “Stroke/prevention and control”, “Stroke/statistics and numerical data” and “Infection”; and 2) using MeSH terms “Stroke/complications”, “Stroke/statistics and numerical data” and “fever”. These searches were undertaken as a preliminary investigation before the main search was performed. However, these searches identified only one article not found by the main search described above, and hence this article was added to the systematic search results. We followed the standard criteria PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) [6] and MOOSE (Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [7] throughout the study.

Selection criteria

These searches resulted in a total of 5294 articles, which were assessed manually first by title, then by abstract and finally by full text. Only studies in English was considered in the process. Grey literature was not included in the process. A selection was made based on the following inclusion criteria, aiming to include articles regardless of study design:

-

Studies of patients with ischemic and/or hemorrhagic stroke.

-

Studies performing multiple logistic regression analysis with the dependent variable pneumonia, UTI or fever (any definition), presenting the results in odds ratio (OR).

Studies including only patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage were excluded. Studies where all patients were treated at intensive care unit or in ventilator were also excluded from the sample.

Data extraction

Author, publication year, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, number of included patients, definitions of outcome measures, study time period and covariates included in the regression model were extracted from all included studies by one investigator. In addition, all available results on predictors of pneumonia, UTI and all-cause fever were extracted.

Certain predictors were described differently in different articles, and categorized according to the following:

-

Mechanical ventilation - Including tracheostomy, endotracheal intubation and endotracheal incision.

-

Dysphagia - Including penetration of liquid on fiber endoscopic evaluation, abnormal bedside swallowing test during admission.

-

Nasogastric tube - Including enteral feeding during admission.

-

Hypertension - Including history of hypertension and hypertension diagnosis.

Quality assessment

Included articles were assessed for risk of bias using a form from the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services [8]. Each study was assessed according to the following fields: Selection bias (A1), Treatment and measurements (A2), Detection bias (A3), Attrition bias (A4), Reporting bias (A5), Conflict of interests (A6).

All fields were assessed and classified as one of the following: low risk of bias, average risk of bias or high risk of bias. In field A2 each article was considered with respect to the measurements of pneumonia, UTI and all-cause fever. Other outcome measures were not taken into account in the quality assessment.

From this assessment, the studies were categorized into three groups regarding quality by following criteria:

-

Low risk of bias –one field to be assessed as average risk

-

Average risk of bias – up to 3 fields assessed as average risk

-

High risk of bias – 4 or more fields assessed as average risk or one field assessed as high risk

The quality assessment was only performed to shed light on the quality of the studies included, and was not used for exclusion of articles.

Statistical analysis

Specific predictors for an outcome were synthesized if at least three articles contributed to the data. The data was analyzed using a random effect model. The overall combined OR with 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-value were calculated. A predictor with a 95% CI not including 1 and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. I2 in percentage with p-values were calculated to describe heterogeneity among studies, I2 > 30% was considered a moderate to high heterogeneity. All the analyses were performed in STATA®14 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas) [9].

Results

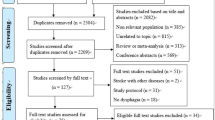

In total, 5294 titles were identified by the searches. After manual screening, 174 articles were left for full text review. After reading the articles in full text, 111 articles were excluded leaving a total of 59 articles to be included in the sample for analysis (Fig. 1). Of these, 47 studied pneumonia, 9 studied UTI, 2 studied both pneumonia and UTI and 1 studied all-cause fever.

After extracting data, only 31 articles in the group studying pneumonia had any of the predictors that were present in at least 3 studies. The 31 articles were included in the meta-analysis. Eighteen other articles [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27] met the initial inclusion criteria, but were later excluded from the meta-analysis: one was excluded because the results were presented with relative risk; all other were excluded because they did not report on predictors existing in 3 or more studies.

Neither UTI nor all-cause fever were possible to analyze because none of the predictors were described in at least 3 studies. Therefore, the results from these were instead presented descriptively in texts.

Predictors of post-stroke pneumonia

The quality assessments of the 31 studies included in the meta-analysis are presented in Table 1. No article included met the criteria of low risk of bias, 17 studies were assessed to have average risk of bias and 14 as having a high risk of bias. Fourteen predictors were presented in 3 or more different studies and synthesized (Table 2). Age (for each year increase), male sex, NIHSS (by one point increase), dysphagia, nasogastric tube, diabetes, mechanical ventilation, smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and atrial fibrillation were statistically significant predictors of post-stroke pneumonia. Previous stroke, dysphagia screening and hypertension were not statistically significantly associated with post-stroke pneumonia. I2s were generally high for all factors in the meta-analysis, indicating high level of heterogeneity.

Predictors of UTI and all-cause fever

Eleven studies reporting predictors of UTI were eligible for meta-analysis, as presented in Table 3. However, since none of their predictors were described in at least 3 studies, no meta-analysis of predictors for UTI was possible. Statistically significant predictors in the individual studies were various laboratory analyses (procalcitonin, c-reactive protein, white blood cell count, monocytes count and copeptin), age, examination with computer tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), use of beta-blocker, female sex, previous pressure ulcer, mean rehabilitation ward stay, three variables pertaining to bladder dysfunction (post void residual volume > 50 ml or > 150 ml and incontinence on admission) and two variables connected to stroke severity (post-stroke modified Rankin Scale and lesion size ≥1.5 cm).

Only one article with all-cause fever as outcome was included (Table 4) after applying the exclusion criteria, and therefore no meta-analysis was possible. Three other articles were excluded because all patients were treated at intensive care units.

Discussion

Several factors in the meta-analyses were associated with post-stroke pneumonia, i.e. age, male sex (with corresponding negative association for female sex), NIHSS, dysphagia, nasogastric tube, diabetes, mechanical ventilation, smoking, COPD and atrial fibrillation. The articles studying UTI and all-cause fever were too few to synthesize. The main aim of the current study was to compile the existing evidence and compare the predictors of post-stroke pneumonia, UTI and all-cause fever. However, since only one meta-analysis was possible, we allow ourselves to make some tentative comparisons between our pneumonia meta-analysis and the studies on UTI and all-cause fever instead.

Some differences between the pneumonia meta-analysis and the eleven UTI articles call for special attention. The most obvious difference was that urinary catheters and other variables connected to bladder dysfunction were associated to UTI in several studies [28,29,30], but not to pneumonia, which reasonably reflects the well-known association between the use of urinary catheters and UTI [31]. In one of the included studies by Brogan et al., incontinence was a predictor of both UTI and pneumonia, possibly because incontinence may serve as a surrogate marker of stroke severity, high age or general frailty [32]. Further, UTI was in one study associated with female sex, mirroring the well-known over-representation of UTI in women [33]. In contrast, our meta-analysis revealed that males were 42% more prone to develop post-stroke pneumonia. This sex-difference may reflect an actual incidence disparity between males and females [34, 35], possibly driven by higher prevalence of current and past smoking in males in these age groups [36]. Another possible explanation is that the results may be biased by the well-known relative under-representation of UTI in males, which may prompt the clinician to suspect airway infections rather than UTI in males with post-stoke fever, while suspecting UTI in women. In addition to the study by Brogan et al. above [32], some of the included studies compared predictors of pneumonia versus UTI. Ingeman et al. [37] found no differences in predicting factors between UTI and pneumonia, while Chen et al. [28] found that ischemic stroke as well as post-void residual volume increased the risk for UTI, while these factors were non-significant for pneumonia.

Comparisons become even more precarious when it comes to all-cause fever, since only one study was found eligible. Further, the patients suffering from all-cause fever reasonably constitute a mix of several different etiologies. Indeed, Muscari et al. [38] (Table 4) found that the strongest predictor of all-cause fever was use of nasogastric tube, which mechanistically ought to be associated with pneumonia, in line with our meta-analysis. Also, they found that urinary catheter was a risk factor for fever, reasonably because UTI caused part of the fevers [38]. An interesting detail was that fever within 24 h after stroke was not significantly related to these infection-associated variables, but rather to variables more connected to stroke severity (NIHSS, hemorrhagic stroke, atrial fibrillation and total parenteral nutrition), which might indicate that early fever to a larger extent is non-infectious [38].

Regarding diabetes, COPD, atrial fibrillation, nasogastric tube and mechanical ventilation, the results of this study corroborates the results of a previous meta-analysis of risk factors for post-stroke lung infection by Yuan et al. [39]. Yuan et al. also showed increased risk for post-stroke lung infections for the variables Age above 65 years, NIHSS 5–15 and NIHSS > 15 [39], which was also confirmed by the current results, even if we analyzed age and NIHSS as continuous variables. In contrast to the current study, Yuan et al. found that male sex and smoking did not significantly increase the risk for post-stroke lung infection, while hypertension and previous stroke did [39]. The study by Yuan et al. adopted wider inclusion criteria, for example not demanding the results to be expressed as odds ratio, which partly could explain these differences [39].

Limitations

The meta-analysis of post-stroke pneumonia showed high rates of heterogeneity, which could suggest that the included studies are not fully comparable. This could at least partly be explained by that the studies included different independent variables in their regression models. Moreover, a majority of the pneumonia articles studied pneumonia or lung-infection during hospitalization, while remaining articles studied pneumonia in a longer time perspective (within 4 days to 30 days post-stroke). Moreover, the studies were included regardless of how they defined pneumonia. Hence, the heterogeneity might be caused by the differences in defining pneumonia in the included studies. To compensate for some of the heterogeneity, only studies performing multiple logistic regressions were included. A further note of caution is that the bias risk of the included studies was generally average or high. Moreover, only one investigator assessed the articles and extracted data, which may limit the reliability of the results. In addition to this only one database was searched, which leaves a possibility that not all relevant studies were included.

Conclusions

We conclude that post-stroke pneumonia is predicted by age, male sex, NIHSS, dysphagia, nasogastric tube, diabetes, mechanical ventilation, smoking, COPD and atrial fibrillation. An opposite relation to sex may exist for UTI, which seems to be more common in women. The lack of studies simultaneously studying a wide range of predictors for UTI or all-cause fever calls for future research in this area. The importance of new research would be to improve our understanding of fever complications to facilitate greater vigilance, monitoring, prevention, diagnosis and treatment..

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NIHSS:

-

National Institute of Health stroke scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Westendorp WF, Nederkoorn PJ, Vermeij JD, Dijkgraaf MG, van de Beek D. Post-stroke infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:110.

Bustamante A, Garcia-Berrocoso T, Rodriguez N, Llombart V, Ribo M, Molina C, Montaner J. Ischemic stroke outcome: a review of the influence of post-stroke complications within the different scenarios of stroke care. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;29:9–21.

Georgilis K, Plomaritoglou A, Dafni U, Bassiakos Y, Vemmos K. Aetiology of fever in patients with acute stroke. J Intern Med. 1999;246(2):203–9.

Reith J, Jorgensen HS, Pedersen PM, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Jeppesen LL, Olsen TS. Body temperature in acute stroke: relation to stroke severity, infarct size, mortality, and outcome. Lancet. 1996;347(8999):422–5.

Azzimondi G, Bassein L, Nonino F, Fiorani L, Vignatelli L, Re G, D'Alessandro R. Fever in acute stroke worsens prognosis. A prospective study. Stroke. 1995;26(11):2040–3.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12.

The Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services, Vår metod. Stockholm: SBU; [updated 2014 / cited 2016–11-11]. Available from: http://www.sbu.se/sv/var-metod.

Palmer TM, STERNE JAC. Meta-analysis in Stata: an updated collection from the Stata journal. Texas: Stata Press Publication; 2016.

Sellars C, Bowie L, Bagg J, Sweeney MP, Miller H, Tilston J, Langhorne P, Stott DJ. Risk factors for chest infection in acute stroke: a prospective cohort study. Stroke. 2007;38(8):2284–91.

Fluri F, Morgenthaler NG, Mueller B, Christ-Crain M, Katan M. Copeptin, procalcitonin and routine inflammatory markers-predictors of infection after stroke. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e48309.

Finlayson O, Kapral M, Hall R, Asllani E, Selchen D, Saposnik G, Canadian Stroke N, Stroke Outcome Research Canada Working G. Risk factors, inpatient care, and outcomes of pneumonia after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2011;77(14):1338–45.

Brogan E, Langdon C, Brookes K, Budgeon C, Blacker D. Respiratory infections in acute stroke: nasogastric tubes and immobility are stronger predictors than dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2014;29(3):340–5.

Zhang X, Yu S, Wei L, Ye R, Lin M, Li X, Li G, Cai Y, Zhao M. The A2DS2 score as a predictor of pneumonia and in-hospital death after acute ischemic stroke in Chinese populations. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150298.

Liu CL, Shau WY, Wu CS, Lai MS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blockers and pneumonia risk among stroke patients. J Hypertens. 2012;30(11):2223–9.

Ishigami K, Okuro M, Koizumi Y, Satoh K, Iritani O, Yano H, Higashikawa T, Iwai K, Morimoto S. Association of severe hypertension with pneumonia in elderly patients with acute ischemic stroke. Hypertens Res. 2012;35(6):648–53.

Bray BD, Smith CJ, Cloud GC, Enderby P, James M, Paley L, Tyrrell PJ, Wolfe CD, Rudd AG, Collaboration S. The association between delays in screening for and assessing dysphagia after acute stroke, and the risk of stroke-associated pneumonia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88(1):25–30.

Dziewas R, Ritter M, Schilling M, Konrad C, Oelenberg S, Nabavi DG, Stogbauer F, Ringelstein EB, Ludemann P. Pneumonia in acute stroke patients fed by nasogastric tube. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75(6):852–6.

Hug A, Murle B, Dalpke A, Zorn M, Liesz A, Veltkamp R. Usefulness of serum procalcitonin levels for the early diagnosis of stroke-associated respiratory tract infections. Neurocrit Care. 2011;14(3):416–22.

Jones EM, Albright KC, Fossati-Bellani M, Siegler JE, Martin-Schild S. Emergency department shift change is associated with pneumonia in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(11):3226–30.

Harms H, Grittner U, Droge H, Meisel A. Predicting post-stroke pneumonia: the PANTHERIS score. Acta Neurol Scand. 2013;128(3):178–84.

Titsworth WL, Abram J, Fullerton A, Hester J, Guin P, Waters MF, Mocco J. Prospective quality initiative to maximize dysphagia screening reduces hospital-acquired pneumonia prevalence in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3154–60.

Masiero S, Pierobon R, Previato C, Gomiero E. Pneumonia in stroke patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: a six-month follow-up study. Neurol Sci. 2008;29(3):139–45.

Herzig SJ, Doughty C, Lahoti S, Marchina S, Sanan N, Feng W, Kumar S. Acid-suppressive medication use in acute stroke and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Ann Neurol. 2014;76(5):712–8.

Lee SY, Chou CL, Hsu SP, Shih CC, Yeh CC, Hung CJ, Chen TL, Liao CC. Outcomes after stroke in patients with previous pressure ulcer: a Nationwide matched retrospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(1):220–7.

Kwan J, Hand P, Dennis M, Sandercock P. Effects of introducing an integrated care pathway in an acute stroke unit. Age Ageing. 2004;33(4):362–7.

Langdon PC, Lee AH, Binns CW. High incidence of respiratory infections in 'nil by mouth' tube-fed acute ischemic stroke patients. Neuroepidemiology. 2009;32(2):107–13.

Chen CM, Hsu HC, Tsai WS, Chang CH, Chen KH, Hong CZ. Infections in acute older stroke inpatients undergoing rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91(3):211–9.

Stott DJ, Falconer A, Miller H, Tilston JC, Langhorne P. Urinary tract infection after stroke. QJM. 2009;102(4):243–9.

Dromerick AW, Edwards DF. Relation of postvoid residual to urinary tract infection during stroke rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(9):1369–72.

Foxman B. Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2014;28(1):1–13.

Brogan E, Langdon C, Brookes K, Budgeon C, Blacker D. Can't swallow, can't transfer, can't toilet: factors predicting infections in the first week post stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22(1):92–7.

Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(5):269–84.

Brogaard SL, Nielsen MB, Nielsen LU, Albretsen TM, Bundgaard M, Anker N, Appel M, Gustavsen K, Lindkvist RM, Skjoldan A, et al. Health care and social care costs of pneumonia in Denmark: a register-based study of all citizens and patients with COPD in three municipalities. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2303–9.

Millett ER, Quint JK, Smeeth L, Daniel RM, Thomas SL. Incidence of community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections and pneumonia among older adults in the United Kingdom: a population-based study. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e75131.

Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, Wollum A, Sanman E, Wulf S, Lopez AD, et al. Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(2):183–92.

Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, Svendsen ML, Johnsen SP. Processes of care and medical complications in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2011;42(1):167–72.

Muscari A, Puddu GM, Conte C, Falcone R, Kolce B, Lega MV, Zoli M. Clinical predictors of fever in stroke patients: relevance of nasogastric tube. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;132(3):196–202.

Yuan MZ, Li F, Tian X, Wang W, Jia M, Wang XF, Liu GW. Risk factors for lung infection in stroke patients: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Expert Rev Anti-Infect Ther. 2015;13(10):1289–98.

Almeida SR, Bahia MM, Lima FO, Paschoal IA, Cardoso TA, Li LM. Predictors of pneumonia in acute stroke in patients in an emergency unit. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2015;73(5):415–9.

Alsumrain M, Melillo N, Debari VA, Kirmani J, Moussavi M, Doraiswamy V, Katapally R, Korya D, Adelman M, Miller R. Predictors and outcomes of pneumonia in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. J Intensive Care Med. 2013;28(2):118–23.

Brogan E, Langdon C, Brookes K, Budgeon C, Blacker D. Dysphagia and factors associated with respiratory infections in the first week post stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;43(2):140–4.

Bruening T, Al-Khaled M. Stroke-associated pneumonia in Thrombolyzed patients: incidence and outcome. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(8):1724–9.

Chumbler NR, Williams LS, Wells CK, Lo AC, Nadeau S, Peixoto AJ, Gorman M, Boice JL, Concato J, Bravata DM. Derivation and validation of a clinical system for predicting pneumonia in acute stroke. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34(4):193–9.

Colbert JF, Traystman RJ, Poisson SN, Herson PS, Ginde AA. Sex-related differences in the risk of hospital-acquired Sepsis and pneumonia post acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25(10):2399–404.

Dziedzic T, Pera J, Klimkowicz A, Turaj W, Slowik A, Rog TM, Szczudlik A. Serum albumin level and nosocomial pneumonia in stroke patients. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13(3):299–301.

Gargano JW, Wehner S, Reeves M. Sex differences in acute stroke care in a statewide stroke registry. Stroke. 2008;39(1):24–9.

Hoffmann S, Malzahn U, Harms H, Koennecke HC, Berger K, Kalic M, Walter G, Meisel A, Heuschmann PU, Berlin Stroke R, et al. Development of a clinical score (A2DS2) to predict pneumonia in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43(10):2617–23.

Hoffmeister L, Lavados PM, Comas M, Vidal C, Cabello R, Castells X. Performance measures for in-hospital care of acute ischemic stroke in public hospitals in Chile. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:23.

Hug A, Dalpke A, Wieczorek N, Giese T, Lorenz A, Auffarth G, Liesz A, Veltkamp R. Infarct volume is a major determiner of post-stroke immune cell function and susceptibility to infection. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3226–32.

Ji R, Shen H, Pan Y, Wang P, Liu G, Wang Y, Li H, Wang Y, China National Stroke Registry I. Novel risk score to predict pneumonia after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(5):1303–9.

Ji R, Shen H, Pan Y, Du W, Wang P, Liu G, Wang Y, Li H, Zhao X, Wang Y, et al. Risk score to predict hospital-acquired pneumonia after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2620–8.

Kwon HM, Jeong SW, Lee SH, Yoon BW. The pneumonia score: a simple grading scale for prediction of pneumonia after acute stroke. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34(2):64–8.

Lakshminarayan K, Tsai AW, Tong X, Vazquez G, Peacock JM, George MG, Luepker RV, Anderson DC. Utility of dysphagia screening results in predicting poststroke pneumonia. Stroke. 2010;41(12):2849–54.

Li Y, Song B, Fang H, Gao Y, Zhao L, Xu Y. External validation of the A2DS2 score to predict stroke-associated pneumonia in a Chinese population: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109665.

Liao CC, Shih CC, Yeh CC, Chang YC, Hu CJ, Lin JG, Chen TL. Impact of diabetes on stroke risk and outcomes: two Nationwide retrospective cohort studies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(52):e2282.

Maeshima S, Osawa A, Hayashi T, Tanahashi N. Elderly age, bilateral lesions, and severe neurological deficit are correlated with stroke-associated pneumonia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23(3):484–9.

Marciniak C, Korutz AW, Lin E, Roth E, Welty L, Lovell L. Examination of selected clinical factors and medication use as risk factors for pneumonia during stroke rehabilitation: a case-control study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88(1):30–8.

Masrur S, Smith EE, Saver JL, Reeves MJ, Bhatt DL, Zhao X, Olson D, Pan W, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, et al. Dysphagia screening and hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with acute ischemic stroke: findings from get with the guidelines--stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(8):e301–9.

Ribeiro PW, Cola PC, Gatto AR, da Silva RG, Luvizutto GJ, Braga GP, Schelp AO, de Arruda Henry MA, Bazan R. Relationship between dysphagia, National Institutes of Health stroke scale score, and predictors of pneumonia after ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;24(9):2088–94.

Scheitz JF, Endres M, Heuschmann PU, Audebert HJ, Nolte CH. Reduced risk of poststroke pneumonia in thrombolyzed stroke patients with continued statin treatment. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(1):61–6.

Smith CJ, Bray BD, Hoffman A, Meisel A, Heuschmann PU, Wolfe CD, Tyrrell PJ, Rudd AG, Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party G. Can a novel clinical risk score improve pneumonia prediction in acute stroke care? A UK multicenter cohort study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(1):e001307.

Sui R, Zhang L. Risk factors of stroke-associated pneumonia in Chinese patients. Neurol Res. 2011;33(5):508–13.

Warnecke T, Ritter MA, Kroger B, Oelenberg S, Teismann I, Heuschmann PU, Ringelstein EB, Nabavi DG, Dziewas R. Fiberoptic endoscopic dysphagia severity scale predicts outcome after acute stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28(3):283–9.

Yamamoto K, Koh H, Shimada H, Takeuchi J, Yamakawa Y, Kawamura M, Miki T. Cerebral infarction in the left hemisphere compared with the right hemisphere increases the risk of aspiration pneumonia. Osaka City Med J. 2014;60(2):81–6.

Zhang X, Wang F, Zhang Y, Ge Z. Risk factors for developing pneumonia in patients with diabetes mellitus following acute ischaemic stroke. J Int Med Res. 2012;40(5):1860–5.

Minnerup J, Wersching H, Brokinkel B, Dziewas R, Heuschmann PU, Nabavi DG, Ringelstein EB, Schabitz WR, Ritter MA. The impact of lesion location and lesion size on poststroke infection frequency. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(2):198–202.

Ersoz M, Ulusoy H, Oktar MA, Akyuz M. Urinary tract infection and bacteriurua in stroke patients: frequencies, pathogen microorganisms, and risk factors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(9):734–41.

Funding

The study was funded by Region Örebro län. Region Örebro län had no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data that the current article is based upon already published material.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MW extracted all data from the articles, contributed to the analyses and drafted the manuscript. YC took part in the statistical analyses. MW, YC and JOS contributed to the study design. All authors (MW, YC and JOS) revised the manuscript critically and approved the final version before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Being a meta-analysis, no ethical approval was needed.

Competing interests

Jakob O Ström has received consultant fee for participation in an Advisory Board for Bayer AB in 2016. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wästfelt, M., Cao, Y. & Ström, J.O. Predictors of post-stroke fever and infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 18, 49 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1046-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-018-1046-z