Abstract

Background

The insular cortex is not routinely removed in modified functional hemispherectomy due to the risk of injury to the main arteries and to deep structures. Our study evaluates the safety and usefulness of applying intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG) on the insular during the hemispherectomy.

Methods

We included all patients who underwent insular ECoG during a modified functional hemispherectomy from 2012 to 2015. After the surgery, the decision for further resection of the insular cortex was made based on the presence of electrographic seizures on ECoG.

Results

The study included 19 patients (age, 6.4 ± 4.7 years, mean ± standard deviation). Electrographic seizures were identified in 5 patients (26.3%). Sixteen of the 19 patients (84.2%) became seizure-free with a follow-up duration of 3.1 ± 0.6 years and no vascular complication occurred.

Conclusions

Intraoperative insular ECoG monitoring can be performed safely while providing a tailored approach for insular resection during modified hemispherectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the literature, the seizure outcome after hemispherectomy in children varies from 52 to 80% upon follow-up 1 year after surgery, and remains stable beyond 5 years at 58–63% [1,2,3,4,5]. The most common cause of surgical failure after hemispherectomy is incomplete disconnection [2]. Common areas of interest include the corpus callosum, frontal basal cortex, and insular cortex. With the use of intraoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we can complete the disconnection of the epileptic hemisphere to the remaining structures in the corpus callosum or frontal basal cortex with high reliability. Although there is a high possibility of insular involvement in intractable epilepsy suggesting hemispheric pathology, the insular cortex is not routinely removed, unless epileptogenic, due to the risk of injury to the main arteries on the surface of the insula and deep structures such as the basal ganglia. An insular seizure is not easily distinguishable from frontal- or temporal-onset seizures based on scalp electroencephalography (EEG) or clinical semiology [6,7,8,9,10]. Since techniques like MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) are not sensitive enough to examine the extent of the involvement of the insular cortex in the epileptogenic zone, stereoelectroencephalography or magnetoencephalography (MEG) are often used [9, 10].

This study aimed to evaluate the safety and usefulness of applying intraoperative insular electrocorticography (ECoG) in modified functional hemispherectomy.

Methods

Patients

We included all patients who underwent intraoperative ECoG monitoring on the insular cortex during modified functional hemispherectomy, at Florida Hospital for Children, from January 2012 to September 2015, and reviewed medical records retrospectively.

Preoperative workup

Patients underwent detailed preoperative evaluation including prolonged video-EEG, 3-Tesla MRI (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), PET with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose, ictal and interictal technetium 99 m single photon emission computed tomography with subsequent subtraction ictal SPECT co-registered with MRI, and neuropsychological evaluation. If required, MEG, functional MRI, and a Wada test were performed. The surgical decision for hemispherectomy was made based on the consensus of the epilepsy board meeting.

Intraoperative procedures

Each patient underwent a modified functional hemispherectomy. After the hemispherectomy without insular resection, ECoG was recorded from frontal and temporal sides of the exposed insular cortex. We used an 8-contact strip electrodes for monitoring insular ECoG and monitored for 3–6 min on each side of insula. Total intravenous anaesthesia with Propofol and Fentanyl was used to minimize effect on cortical electrical activity during ECoG. No pharmacological activation was introduced during the recording. We removed the insular cortex if an electrographic seizure was recorded on the insular ECoG.

Pathology results and outcome

Pathological findings were reported based on the consensus of International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) diagnostic methods commission [11]. The seizure outcome was classified based on the ILAE classifications [12].

Results

Patient profile

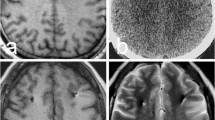

A total of 19 patients were included in the current study (Table 1). Five patients (26.3%) had epilepsy surgery before hemispherectomy, three (15.8%) patients had an MRI suggestive of insular involvement (Fig. 1a), and four (21.1%) patients underwent intracranial EEG monitoring to confirm hemispheric involvement, since their MRIs did not clearly show hemispheric pathology (data not shown).

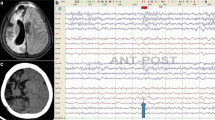

Insular hyperintensity shown on fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery MRI. 3-Tesla axial fluid-attenuated inversion-recovery images at the insular level show insular hyperintensity (a, arrow). The patient had an electrographic seizure on frontal strip of insular ECoG (b), which disappeared after insular resection (c)

Intraoperative insular electrocorticography

In the entire cohort, electrographic seizures were identified in five patients (26.3%) by post-resection intraoperative ECoG on the insular cortex (Fig. 1b), of whom one patient had previous epileptic surgery, while another had brain tumor surgery after birth. Further, of the five patients, one had Rasmussen encephalitis, one had hemimegalencephaly, and three had diffuse malformation of cortical development (MCD). The characteristics of the patient with positive insular seizure are shown in Table 2.

Consistency between MRI and ECoG

As noted in Table 3, MRI was not always predictive of the presence of an insular seizure: MR fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) image showed no abnormality on insular cortex in 3 of 5 patients with an insular seizure, while MRI was abnormal on insular cortex in one patient without an insular seizure.

Presence of insular seizure according to etiology

Histopathological analyses revealed MCD as the most common etiology (10/19, 52.6%, Table 4), followed by perinatal stroke (6/19, 31.6%). Of them, insular seizures were identified on ECoG in 5 patients (26.3%) and pathology showed as follows: one with hemimegalencephaly, one with Rasmussen and three with diffuse malformations of cortical development. None of six perinatal stroke patients showed electrographic seizures on the insular ECoG. However, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.128).

Outcome

In the current study, 16 of the 19 patients (84.2%) became seizure free with a median follow-up of 3.1 ± 0.6 years (mean ± standard deviation) (Table 5). Four out of 5 patients (80%) with electrographic seizures on insular ECoG became seizure-free and one patient had breakthrough seizures with the onset from basal frontal brain area. Twelve of 14 patients (80%) without insular ECoG abnormality became seizure-free. Two patients with abnormality on both imaging and ECoG and one patient with an abnormal imaging but normal ECoG became seizure-free after surgery. Two patients developed hydrocephalus, and the disconnection was incomplete in the corpus callosum or basal frontal area in three patients. None of the patients developed perioperative stroke.

Discussion

In the current study, although electrographic seizures were detected on the insular ECoG in five patients (5/19; 26.3%), only two of these patients demonstrated subtle high signal intensity in the insular cortex on FLAIR images. These five patients underwent removal of the insular cortex in addition to functional hemispherectomy, and 84.2% of the patients in the current cohort were seizure-free with a mean follow-up duration of 3.1 years.

We believe the use of insular ECoG should be considered in all modified hemispherectomy cases for two reasons. Firstly, there is a relatively high possibility of insular involvement in hemispherectomy candidates. The existence of bidirectional interconnections between the amygdalo-hippocampal formation and the insula was confirmed by an electrophysiological study [13]. Given that the amygdalo-hippocampal formation is the most commonly involved brain structure in intractable epilepsy, the insular cortex should be considered the critical part of the epileptic network in these children. The residual insular cortex was positively correlated with persistent postoperative seizures in failed hemispherectomy patients [14].

Secondly, insular seizures could be indistinguishable from frontal or temporal lobe onset seizures [6,7,8,9,10]. The insular cortex is deeply located, buried in the lateral sulcus, and covered by the operculum, making it hard to detect using scalp EEG.

Although some previous research favored insular removal in hemispherectomy [15,16,17], others did not support it [2, 18]. Some centers routinely remove the insular cortex during hemispherectomy to prevent the potential development of persistent seizures [19, 20]. However, the routine removal of the insular cortex is not widely accepted at this point, due to the risk of injury to arteries and deep structures surrounding the insula (the average distance from the limen insulae to the putamen is only 5.7 mm [21]).

The current study also suggests the possible correlation between the pathology and the insular seizures on ECoG, although it did not reach the clinical significance. Except one patient with Rasmussen encephalitis, all 4 patients with electrographic seizures on insular ECoG had a developmental etiology; three had MCD and one had hemimegalencephaly. None of the five perinatal stroke patients showed insular seizure. These results suggest that developmental malformation commonly occurs in a more diffuse pattern, increasing the chances of insular cortex involvement. Due to the small number of patients in each pathology group, further research is required to validate the correlation between pathology and the involvement of the insular cortex in the epileptic network.

Our data support the use of insular ECoG as a safe and sensitive method to detect insular involvement in hemispherectomy patients. None of the 19 patients developed stroke or infection.

Limitations in the current study must be noted. The average duration of postoperative follow-up was less than 5 years. A recent multicenter study suggested that complications such as hydrocephalus could occur even after 8.5 years [22] and seizure outcome may change with a longer duration of follow-up [4]. In addition, intraoperative ECoG findings are not always predictive of postoperative seizure recurrence. Only a randomized controlled study could answer whether insular ECoG truly contributes to a better surgical outcome following hemispherectomy.

Conclusions

Intraoperative insular ECoG monitoring could be performed safely without adding risk while providing a tailored approach to insular removal. Patients with developmental malformation may benefit from this approach.

Abbreviations

- ECoG:

-

Electrocorticography

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalography

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- ILAE:

-

International League Against Epilepsy

- MCD:

-

Malformations of cortical development

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

References

Hamad AP, Caboclo LO, Centeno R, Costa LV, Ladeia-Frota C, Carrete Junior H, Gomez NG, Marinho M, Yacubian EMT, Sakamoto AC. Hemispheric surgery for refractory epilepsy in children and adolescents: outcome regarding seizures, motor skills and adaptive function. Seizure. 2013;22(9):752–6.

González-Martínez JA, Gupta A, Kotagal P, Lachhwani D, Wyllie E, Lüders HO, Bingaman WE. Hemispherectomy for catastrophic epilepsy in infants. Epilepsia. 2005;46(9):1518–25.

Lettori D, Battaglia D, Sacco A, Veredice C, Chieffo D, Massimi L, Tartaglione T, Chiricozzi F, Staccioli S, Mittica A. Early hemispherectomy in catastrophic epilepsy: a neuro-cognitive and epileptic long-term follow-up. Seizure. 2008;17(1):49–63.

Moosa AN, Gupta A, Jehi L, Marashly A, Cosmo G, Lachhwani D, Wyllie E, Kotagal P, Bingaman W. Longitudinal seizure outcome and prognostic predictors after hemispherectomy in 170 children. Neurology. 2013;80(3):253–60.

Jonas R, Nguyen S, Hu B, Asarnow R, LoPresti C, Curtiss S, De Bode S, Yudovin S, Shields W, Vinters H. Cerebral hemispherectomy hospital course, seizure, developmental, language, and motor outcomes. Neurology. 2004;62(10):1712–21.

Ryvlin P, Minotti L, Demarquay G, Hirsch E, Arzimanoglou A, Hoffman D, Guénot M, Picard F, Rheims S, Kahane P. Nocturnal hypermotor seizures, suggesting frontal lobe epilepsy, can originate in the insula. Epilepsia. 2006;47(4):755–65.

Dobesberger J, Ortler M, Unterberger I, Walser G, Falkenstetter T, Bodner T, Benke T, Bale R, Fiegele T, Donnemiller E. Successful surgical treatment of insular epilepsy with nocturnal hypermotor seizures. Epilepsia. 2008;49(1):159–62.

Levitt MR, Ojemann JG, Kuratani J. Insular epilepsy masquerading as multifocal cortical epilepsy as proven by depth electrode: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010;5(4):365–7.

Heers M, Rampp S, Stefan H, Urbach H, Elger CE, von Lehe M, Wellmer J. MEG-based identification of the epileptogenic zone in occult peri-insular epilepsy. Seizure. 2012;21(2):128–33.

Dylgjeri S, Taussig D, Chipaux M, Lebas A, Fohlen M, Bulteau C, Ternier J, Ferrand-Sorbets S, Delalande O, Isnard J. Insular and insulo-opercular epilepsy in childhood: an SEEG study. Seizure. 2014;23(4):300–8.

Blümcke I, Thom M, Aronica E, Armstrong DD, Vinters HV, Palmini A, Jacques TS, Avanzini G, Barkovich AJ, Battaglia G. The clinicopathologic spectrum of focal cortical dysplasias: a consensus classification proposed by an ad hoc task force of the ILAE diagnostic methods Commission1. Epilepsia. 2011;52(1):158–74.

Wieser H, Blume W, Fish D, Goldensohn E, Hufnagel A, King D, Sperling M, Lüders H, Pedley TA. Proposal for a new classification of outcome with respect to epileptic seizures following epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 2001;42(2):282–6.

Zonjy B, Alkhachroum A, Kahriman E, Lacuey N, Miller J, Luders H. Functional connectivity between Insula, hippocampus, and Amygdala investigated using Cortico-cortical evoked potentials (CCEPs)(S50. 005). Neurology. 2014;82(Suppl 10):S50–005.

Cats EA, Kho KH, Van Nieuwenhuizen O, Van Veelen CW, Gosselaar PH, Van Rijen PC. Seizure freedom after functional hemispherectomy and a possible role for the insular cortex: the Dutch experience. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2007;107(4):275–80.

Cook SW, Nguyen ST, Hu B, Yudovin S, Shields WD, Vinters HV, BMVd W, Harrison RE, Mathern GW. Cerebral hemispherectomy in pediatric patients with epilepsy: comparison of three techniques by pathological substrate in 115 patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2004;100(2):125–41.

Kaido T, Otsuki T, Kakita A, Sugai K, Saito Y, Sakakibara T, Takahashi A, Kaneko Y, Saito Y, Takahashi H. Novel pathological abnormalities of deep brain structures including dysplastic neurons in anterior striatum associated with focal cortical dysplasia in epilepsy: clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;10(3):217–25.

Nguyen DK, Nguyen DB, Malak R, Leroux JM, Carmant L, Saint-Hilaire JM, Giard N, Cossette P, Bouthillier A. Revisiting the role of the insula in refractory partial epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009;50(3):510–20.

Villemure J, Mascott C, Andermann F, Rasmussen T. Is removal of the insular cortex in hemispherectomy necessary. Epilepsia. 1989;30(Suppl):728.

Schramm J, Kuczaty S, Sassen R, Elger C, von Lehe M. Pediatric functional hemispherectomy: outcome in 92 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2012;154(11):2017–28.

Villemure J-G, Mascott CR. Peri-insular hemispherotomy: surgical principles and anatomy. Neurosurgery. 1995;37(5):975–81.

Tanriover N, Rhoton AL Jr, Kawashima M, Ulm AJ, Yasuda A. Microsurgical anatomy of the insula and the sylvian fissure. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(5):891–922.

Lew SM, Matthews AE, Hartman AL, Haranhalli N. Posthemispherectomy hydrocephalus: results of a comprehensive, multiinstitutional review. Epilepsia. 2013;54(2):383–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The de-identified data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GHK acquired the data, conducted all of the data analyses and wrote the article. JHS and FA helped providing data, interpreted the data, and checked the final version of the article. KHL and JEB conceptualized the study design, analyzed and interpreted the data and revised the article. All of the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Florida Hospital for Children. Patients’ informed consents were waived because of the retrospective and observational nature of this study. All data are fully de-identified. No data (personal or clinical) from any individual participant are reported in this manuscript.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, GH., Seo, J.H., Baumgartner, J.E. et al. Usefulness of intraoperative insular electrocorticography in modified functional hemispherectomy. BMC Neurol 17, 162 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0940-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-017-0940-0