Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is identified as the pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2). The intravascular thrombotic phenomena related to the COVID-19 are emerging as an important complication that contribute to significant mortality.

Case presentation

We present a 62-year-old man with severe COVID-19 and type 2 diabetes. After symptomatic and supportive treatment, the respiratory function was gradually improved. However, the patient suddenly developed abdominal pain, and the enhanced CT scan revealed renal artery thrombosis. Given the risk of surgery and the duration of the disease, clopidogrel and heparin sodium were included in the subsequent treatment. The patient recovered and remained stable upon follow-up.

Conclusions

Thrombosis is at a high risk in patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia because of hypercoagulable state, blood stasis and endothelial injury. Thrombotic events caused by hypercoagulation status secondary to vascular endothelial injury deserves our attention. Because timely anticoagulation can reduce the risk of early complications, as illustrated in this case report.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The past research shows that COVID-19 can cause arteriovenous thromboembolism in most organ systems [1,2,3]. Among them, what is particularly striking is the correlation between SARS-CoV-2 infection and renal artery thrombosis [1, 2]. Although the mechanism of COVID-19 complicated by renal vascular thrombosis is not yet fully understood, scholars speculate that it may be the direct pathogenic effect of SARS-CoV-2 on endothelial cells and microvascular damage, or it may be related to the hypercoagulable state of the blood [4]. Severe COVID-19 pneumonia is associated with a coagulopathic state and may increase the risk of thrombotic complications [5]. The current common thrombotic complications mainly include venous thrombosis events, pulmonary thrombosis, and myocardial infarction. However, we have noted that reports of embolization events that occur in renal arteries are rare. We present a case of renal artery thrombosis in a SARS-CoV-2-positive patient.

Case presentation

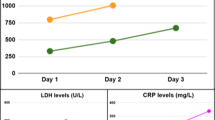

A 62-year-old man with a history of type 2 diabetes presented with fever that started 5 days ago. Cough, fatigue, or abdominal pain were not present. At admission, the body temperature was 36.7 °C, and the patient was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay. Vital signs on presentation revealed heart rate of 76 beats/minute, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/minute, and blood pressure of 117/65 mmHg. A chest computed tomography scan showed ground glass-like shadows multiple consolidations in the both upper lobes (Fig. 1 A to B). The initial peripheral blood sample showed that the coagulation function was normal and the LDH was 274 U/L (Table 1). The patient had no history of valvular heart disease, atrial fibrillation or urinary system disease. The electrocardiogram indicates sinus rhythm. The creatinine value is 71 μmol/L. Urinalysis results are normal. The rest of the physical examination was also unremarkable.

According to the fifth edition of Chinese New Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection Treatment Plan Guide [6], the coronavirus pneumonia diagnosed was classified as mild type. He agreed to be given routine antiviral treatment and glycemic management of diabetes. Three days later, the patient developed shortness of breath and the symptom gradually worsened. The blood gas analysis showed an oxygenation index result of 172. After a regimen of 4-day course of methylprednisolone and ceftriaxone, his physical condition showed a significant improvement. On day 12 of hospitalization, the patient reported sudden-onset severe pain in the left waist. Abdominal and urinary color doppler ultrasound at that time showed no abnormalities. Two days later, laboratory tests displayed significantly elevated d-dimer level of 1008 ng/ml, creatinine level of 116 umol/L, and LDH level of 576 U/L. Urine routine showed urinary occult blood 2 + and protein 2 +. Table 1 shows the results of the second peripheral blood test. The enhanced CT scan revealed the left renal artery embolism and threatening ischemia (Fig. 2 A to F). The electrocardiogram of this patient showed sinus rhythm, and there was no history of cardiac valvular disease and atrial fibrillation, which did not support cardiogenic embolism, so it was diagnosed as renal artery thrombosis, resulting in acute renal artery embolism. Although the patient did not have obvious contraindications to thrombolysis, thrombosis occurred in the renal artery branch, interventional procedures were difficult and risky. The patient was diagnosed as renal artery thrombosis 48 hours after the onset of symptoms, and thrombolytic reperfusion therapy may not be beneficial. The patient had not received any anticoagulant therapy before. Considering that the process of renal artery thrombosis involves platelet activation and aggregation, clopidogrel antiplatelet aggregation therapy (clopidogrel 300 mg with 75 mg daily) and nadroparin calcium (3800 IU/q12h) anticoagulant therapy were given. Three days later, clopidogrel combined with rivaroxaban was used to maintenance therapy. The patient was discharged from the hospital after 1 week of anticoagulation therapy, with disappearance of lumbago, negative lumbar percussion pain, reexamination of D-dimer and renal function, and normal urinary routine. After that, the patient continued to receive the above anticoagulant regimen for 3 months. After 3 months, the patient returned to the hospital for reexamination, indicating that the renal function was normal.

Discussion and conclusion

In this case, renal artery thrombosis suddenly occurred during the treatment of COVID-19 and subsequently led to left renal threatening ischemia. The laboratory test indicating thrombotic complications was elevated D-dimer. Previous studies have shown that elevated D-dimer was a risk factor for death in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially in elderly patients [7, 8]. The hypercoagulation status of COVID-19 and the subsequent series of vascular complications are a vital topic that is currently emerging [9]. Previous reports have suggested that patients with renal artery thrombosis were patients with atrial fibrillation or had a history of renal artery stenting. Interestingly, the patient in this case had no history of atrial fibrillation or renal artery surgery, and the occurrence of renal artery thrombosis suggested that it was related to vascular damage and coagulation function changes in novel Coronavirus. This has implications for future renal injury complications from COVID-19 [10,11,12]. The question of anticoagulant therapy at prophylaxis dose or even higher was subsequently raised [13]. It has been suggested that immune-mediated reaction or direct viral infection of the endothelium will lead to recruitment of immune cells, which may develop into extensive endothelial dysfunction [14]. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors are expressed in organs including lung, heart, kidney and intestine. Vascular endothelial cells also express angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. And the virus can directly infect endothelial cells by converting enzyme 2 and cause diffuse endothelial inflammation [15]. SARS-CoV-2 infection can develop into acute respiratory distress syndrome. Similar to other viral infections, early cytokine storms are caused by overproduction of response proinflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor, interleukin-6 and interleukin-1 β, resulting in an increased risk of multiorgan failure and vascular hyperpermeability [16]. The main function of thrombin in the immune response is to promote the formation of clots by activating platelets and converting fibrinogen to fibrin. However, it is worth noting that the cellular effect of thrombin, mainly par-1 (proteinase-activated receptors), can further enhance inflammation [17]. Protein C system, tissue factor pathway inhibitor and antithrombin are defective during inflammation, which impairs the coagulant–anticoagulant balance and leads to the formation of microthrombus [18]. The hypercoagulation status of blood caused by the infection of SARS-CoV-2 can lead to a variety of intravascular thrombotic phenomena, ranging from limited venous and arterial thrombosis to fatal disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Thrombotic events caused by hypercoagulation status secondary to vascular endothelial injury deserves our attention. Because timely anticoagulation can reduce the risk of early complications.

Availability of data and materials

If required, the relevant material can be provided by corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV2:

-

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

References

Mukherjee A, Ghosh R. Furment MM case report: COVID-19 associated renal infarction and ascending aortic thrombosis. Am J Tropical Med. 2020;103:1989–92.

Tomasoni D, Adamo M, Italia L, Branca L, Chizzola G, Fiorina C, et al. Impact of COVID-2019 outbreak on prevalence, clinical presentation and outcomes of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Med. 2020;21:874–81.

Post A, den Deurwaarder ESG, Bakker SJL, de Haas RJ, van Meurs M, Gansevoort RT, et al. Kidney infarction in patients with COVID-19. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:431–5.

Basara Akin I, Altay C, Eren Kutsoylu O. Secil M possible radiologic renal signs of COVID-19. Abdom Radiol. 2021;46:692–5.

Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020; 2020.04.013.

Lin L, Li TS. Interpretation of "guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of novel coronavirus (2019-ncov) infection by the national health commission (trial version 5)". Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;100:E001.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62.

Arachchillage DRJ, Laffan M. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thrombosis, haemostasis: JTH. 2020;18(5):1233–4.

Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;185(5):1023–6.

El Shamy O, Munoz-Casablanca N, Coca S, Sharma S, Lookstein R, Uribarri. Bilateral renal artery thrombosis in a patient with COVID-19. J Kidney medicine. 2021;3:116–9.

Singh T, Chaudhari R. Gupta a renal artery thrombosis and mucormycosis in a COVID-19 patient. Indian J Urol. 2021;37:267–9.

Philipponnet C, Aniort J, Chabrot P, Souweine B. Heng AE renal artery thrombosis induced by COVID-19. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13:713.

Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thrombosis. 2020;18(5):1094–9.

Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–8.

Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2605–10.

Meduri GU, Kohler G, Headley S, Tolley E, Stentz F, Postlethwaite A. Inflammatory cytokines in the BAL of patients with ARDS. Persistent elevation over time predicts poor outcome. Chest. 1995;108(5):1303–14.

José RJ, Williams AE, Chambers RC. Proteinase-activated receptors in fibroproliferative lung disease. Thorax. 2014;69(2):190–2.

Jose RJ, Manuel A. Respiratory medicine COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30216-2.

Acknowledgements

We want to express our gratitude to The First People’s Hospital of Fang Cheng Gang City for help and support.

Funding

This report was supported by The First People’s Hospital of Fang Cheng Gang City and the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. The funders had no role in the design of the study or in the collection analysis or interpretation of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HYH, CGL, YDC and SQC contributed in the analysis and interpretation of data; HYH, XTW and MML drafted the work. YDC and KL revised the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient approved of publishing this manuscript and signed a written informed consent. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors in this study have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, H., Lin, C., Chen, Y. et al. Renal artery thrombosis in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case report. BMC Nephrol 23, 175 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02808-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-022-02808-5