Abstract

Background

Recent studies have shown associations between contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) and increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); however, the estimates are inconsistent and vary widely. Therefore, this meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the precise associations between CI-AKI and adverse clinical consequences in patients undergoing PCI for ACS.

Methods

EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science™ and Cochrane Library databases were systematically searched from inception to December 16, 2016 for cohort studies assessing the association between CI-AKI and any adverse clinical outcomes in ACS patients treated with PCI. The results were demonstrated as pooled risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity was explored by subgroup analyses.

Results

We identified 1857 articles in electronic search, of which 22 (n = 32,781) were included. Our meta-analysis revealed that in ACS patients undergoing PCI, CI-AKI significantly increased the risk of adverse clinical outcomes including all-cause mortality (18 studies; n = 28,367; RR = 3.16, 95% CI 2.52–3.97; I2 = 56.9%), short-term all-cause mortality (9 studies; n = 13,895; RR = 5.55, 95% CI 3.53–8.73; I2 = 60.1%), major adverse cardiac events (7 studies; n = 19,841; RR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.34–1.65; I2 = 0), major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (3 studies; n = 2768; RR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.42–2.43; I2 = 0) and stent restenosis (3 studies; n = 130,678; RR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.24–1.81; I2 = 0), respectively. Subgroup analyses revealed that the studies with prospective cohort design, larger sample size and lower prevalence of CI-AKI might have higher short-term all-cause mortality risk.

Conclusions

CI-AKI may be a prognostic marker of adverse outcomes in ACS patients undergoing PCI. More attention should be paid to the diagnosis and management of CI-AKI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), including ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina (UA), is one of the most dangerous presenting conditions. It usually results from the abrupt reduction of coronary blood flow caused by the ruptured coronary atherosclerotic lesion and superimposed acute thrombosis. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended as a first-line treatment of the reperfusion strategy and it contributes to the salvage of the myocardium and improvement of the prognosis [1,2,3]. However, even after successful PCI, both the short-and long-term morbidity and mortality of ACS patients undergoing PCI are alarmingly high [4,5,6]. Therefore, it is critical to investigate the risk factors associated with worse outcomes.

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI), also known as contrast-induced nephropathy, is a frequent complication of PCI due to the use of iodinated contrast agent [7,8,9,10]. In particular, patients who underwent primary PCI are at higher risk of CI-AKI than those treated with elective PCI due to hemodynamic instability and lack of adequate renal prophylactic therapy [8, 11]. The primary manifestation is the mild decline in renal function, occurring 1 to 3 days after contrast media exposure. According to several reports, CI-AKI after PCI for ACS was associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including all-cause mortality [12,13,14], short-term in-hospital mortality [15,16,17], major adverse cardiac events (MACE) [18,19,20], major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) [21,22,23] and stent restenosis [19, 24, 25]. However, several other studies demonstrated the inconsistent results [26, 27]. In addition, the evaluated values among studies varied widely. For example, the increased risk of all-cause mortality for CI-AKI patients after PCI for ACS varied from 54% [26] to 799% [17].

The aim of the present meta-analysis was to evaluate the associations between CI-AKI and adverse clinical consequences, including all-cause mortality, short-term all-cause mortality, MACE, MACCE and stent restenosis in patients undergoing PCI for ACS.

Methods

Our study was designed, conducted and reported based on Preferred.

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

guidelines (see Additional file 1) [28].

Search strategy

EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science™ and Cochrane Library databases were systematically searched from inception to December 16, 2016 using Google Chrome software with following terms: “acute myocardial infarction”, “AMI”, “myocardial infarction”, “MI”, “non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction”, “ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction”, “acute coronary syndrome”, “ACS”, “unstable angina”, “acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction”, “acute non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction”, “complete revascularization”,“revascularization”, “revascularization”, “percutaneous coronary intervention”, “PCI”, “contrast-induced acute kidney injury”, “contrast-induced nephropathy”, “contrast media use”, “CIN”, “CI-AKI”, “mortality”, “cardiovascular”, “events”, “death”, “outcome”, “Hemodialysis”, “Haemodialysis”, “Dialysis”, “peritoneal dialysis”, “Adverse effect”, “prognosis”, “chronic kidney disease”, “CKD”, “end-stage renal disease”, “ESRD” (see Additional file 2). Furthermore, we searched the reference lists of included articles for additional studies. The full text of a record was reviewed if there was any doubt to the eligibility of it. Two of the authors (Y.Y. and K.G.) independently screened titles and abstracts, analyzed full-text articles, and ascertained the final eligible records. Divergences were resolved by discussion or consulting a third author.

Selection criteria

We selected articles that (1) were cohort studies published as original studies, (2) enrolled the populations of general PCI-treated ACS patients, including acute myocardial infarction, non ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris or ACS (i.e., without any additional pathologies, neither be given other special operation or interventional therapy), (3) observed the exposure of CI-AKI with clear definition, (4) evaluated the associations between CI-AKI and risk of any clinical outcomes during follow-up, and quantitative effect size could be extracted, calculated or obtained from original authors, including relative risks, hazard ratios or odds ratios (RRs, HRs or ORs) and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and (6) had no restriction of language.

Exclusion criteria

Studies should be excluded by the following criteria: (1) meta-analyses, reviews, editorials, meeting abstracts, comments, letters, notes, animal studies, case-control and cross-sectional studies were excluded; (2) we could not extract available data from the published result, and the authors did not reply our request for more data; (3) only one or two studies evaluated the association between CI-AKI and risk of the same outcome.

If two articles were from the same cohort but reported the different outcomes, we included both; otherwise, we included the most informative study.

Data extraction

We extracted the information of interest from each study including study characteristics (study group name, publication year, geographical location, study design, sample size, clinical scenario, age at baseline, male percentage, follow-up duration, prevalence of CI-AKI, CI-AKI definition, smoker percentage, body mass index, Killip class, left ventricular ejection fraction, baseline serum creatinine, baseline eGFR, Family history for coronary artery disease), complication (prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipemia), diseases’ history (myocardial infarction, previous coronary bypass surgery, PCI), medications for ACS (Aspirin, ACEI/ARB, β-blocker, Statins), use of contrast volume and confounder-adjusted and unadjusted risk estimates (including RRs, HRs and ORs) and 95% CIs for any adverse outcome. All outcomes in our eligible articles included all-cause mortality, in-hospital mortality, 30-day mortality, cardiovascular mortality, MACE, MACCE, stent restenosis, reinfarction and major bleeding. We conducted meta-analyses if more than two studies had available data for an outcome. Two authors independently extracted data using standardized tables and resolved discrepancies through discussion and consensus. We made a request to the corresponding author of original studies for further information when necessary and included it if responses were obtained.

Quality assessment

We evaluated the quality of studies using Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) of cohort studies [29] which assessed the following: (1) exposed cohort truly or somewhat representative, (2) non-exposed cohort drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort, (3) ascertainment of exposure, (4) outcome of interest not present at start, (5) study controls for age, (6) study controls for≥3 additional risk factors, (7) assessment of outcome (independent blind assessment or record linkage), (8) follow-up≥24 m, (9) complete accounting for cohorts or subjects lost to follow-up unlikely to introduce bias. This scale allocates a maximum of 9 points for quality of study participants. Overall study quality was graded as good (score, 7–9), fair (score, 4–6), or poor (score, 0–3) [30]. Two authors performed the quality assessment independently and divergence was resolved by discussion or consensus.

Statistical analysis

The studies included in our analysis reported different effect measures (HRs, RRs or ORs). The RR was used as a common measure of association across studies. We combined HRs as RRs in our article. OR was transformed into RR according to the formula RR = OR/[(1-P0) + (P0 × OR)] where P0 stands for the incidence of CI-AKI whenever possible [31]. Otherwise, ORs was considered as RRs because of the low incidence of CI-AKI. Heterogeneity of RRs across included studies was examined using χ2 based on Q-statistical test and quantified by I2 index. Roughly, heterogeneity was considered significant if P < 0.10 and Higgins I2 values of 25, 50, and 75% were respectively considered as low, moderate, and high inconsistencies. We used random effects models when there was obvious heterogeneity among studies (I2 ≥ 50%); otherwise fixed effects models were used. Publication bias was assessed through Begg’s and Egger’s testing (P < 0.10 was significant) as well as funnel plot. Jackknife sensitivity analyses were conducted by recalculating pooled RRs with the removal of a single study once from the baseline group. To explore the source of heterogeneity, subgroup meta-regressions were conducted. All analyses and graphs were made using Stata 10.0 (College Station, TX, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6. P < 0.05 by 2 tailed were set to be significant.

Results

Literature search

We identified 1857 articles in a systematic electronic search, of which 22 [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, 32,33,34,35,36,37] articles were included for the current meta-analysis after detailed evaluation (Fig. 1). No additional article was found through manual search of the reference lists in these studies.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 22 included studies (prospective: 12; retrospective: 10) were summarized in Table 1. Studies were published between 2003 and 2016, and 13 were from Asia, 5 from Europe, 3 from North America and 1 from Australia. The number of participants ranged from 194 to 3822 (32,781 in total, male: 75.9%), and the mean age ranged from 56.4 and 69.0 years across studies. CI-AKI occurred in 4809 patients (14.6%) on average. The definition of CI-AKI varied among the trials. Other relevant characteristics, complications, previous history and medications were shown in Additional files 3 and 4.

Quality of included studies

The NOS scores for included studies were detailed in Fig. 2. Overall, 18 (81.8%) studies were regarded to be of good methodological quality and the remaining 4 studies [17, 27, 32, 37] were considered to be of fair quality.

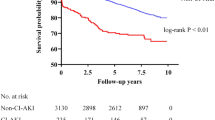

CI-AKI and risk of all-cause mortality

Of the 22 cohorts included, 18 studies (16 with adjusted RR [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, 23, 24, 26, 33,34,35] and 2 with crude RR [32, 36]) investigated the association between CI-AKI and risk of all-cause mortality for a total pooled population of 28,367 patients after PCI for ACS. Overall, CI-AKI was associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality (pooled RR 3.16; 95% CI 2.52–3.97; Q statistic P = 0.002; I2 = 56.9%; Fig. 3a). Notably, this data set was heterogeneous, thus random effects model was used for the analysis.

Association between contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI) and risk of adverse clinical outcomes. a all-cause mortality, (b) short-term all-cause mortality, (c) major adverse cardiac events (MACE), (d) major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE) and (e) stent restenosis. Abbreviations: RR, risk ratio

CI-AKI and risk of short-term all-cause mortality

Of the 22 cohorts included, 7 studies investigated the association between CI-AKI and risk of in-hospital mortality [12, 13, 15,16,17, 19, 36], and 2 studies [32, 33] investigated the association between CI-AKI and risk of 30-day mortality for a total number of 13,895 patients after PCI for ACS. These 9 studies (7 with adjusted RRs [12, 13, 15,16,17, 19, 33] and 2 with crude RRs [32, 36]) were pool-evaluated using random-effects model with moderate heterogeneity, and revealed that CI-AKI was significantly associated with increased risk of short-term all-cause mortality (pooled RR 5.55; 95% CI 3.53–8.73; Q statistic P = 0.010; I2 = 60.1%; Fig. 3b).

CI-AKI and risk of MACE, MACCE and stent restenosis

For ACS patients treated with PCI, CI-AKI increased the risk of MACE (7 studies [18,19,20, 24, 27, 33, 37]; n = 19,841; pooled RR 1.49, 95% CI: 1.34–1.65; Q statistic P = 0.686; I2 = 0; Fig. 3c), MACCE (3 studies [21,22,23]; n = 2768; pooled RR 1.86, 95% CI: 1.42–2.43; Q statistic P = 0.697; I2 = 0; Fig. 3d) and stent restenosis (3 studies [19, 24, 25]; n = 130,678; pooled RR 1.50, 95% CI: 1.24–1.81; Q statistic P = 0.748; I2 = 0; Fig. 3e), respectively. These data were not heterogeneous (all Q statistic P > 0.1 and all I2 = 0); therefore, fixed effects models were used for analyses.

Subgroup analyses

For all-cause mortality and short-term all-cause mortality, we further conducted subgroup meta-analysis. Figure 4 showed possible confounding factors and outcomes. In the subgroups of prospective study, sample size< 1500, mean age ≥ 62 years old, CI-AKI (%) ≥ 14.5, hypertension (HT) (%) ≥ 55, diabetes mellitus (DM) (%) ≥ 24.2 and hyperlipidemia (HLP) (%) ≥ 48 for all-cause mortality, and the subgroups of prospective study, sample size< 1500, sample size≥1500, mean age ≥ 60 years old, CI-AKI (%) < 13.6, CI-AKI (%) ≥ 13.6, HT (%) ≥ 53, DM (%) ≥ 23.4 and elective PCI for short-term all-cause mortality, no statistical heterogeneity was detected (all P values > 0.1). Even though all differences were not significant (all P > 0.05 in meta-regression analysis), an obvious difference of pooled RRs occurred in studies with different sample sizes for all-cause mortality, while obvious differences of pooled RRs were found in studies with different study design, sample size and prevalence of CI-AKI for short-term all-cause mortality (Fig. 4).

Subgroup and meta-regression analysis for all-cause mortality and short-term all-cause mortality. Abbreviations: RR, risk ratio; PC, prospective; RC, retrospective; CI-AKI, CI-AKI, contrast-induced acute kidney injury; HT, hypertension; DM, diabetes mellitus; HLP, hyperlipidemia; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. Hint: the cut points for all-cause mortality: sample size, 1500; mean age, 62 years old; prevalence of CI-AKI, 14.5%; prevalence of HT, 55%; prevalence of DM, 24.2%; prevalence of HLP, 48%; prevalence of smoker, 47.5% and for short-term all-cause mortality: sample size, 2000; mean age, 60 years old; prevalence of CI-AKI, 13.6%; prevalence of HT, 53%; prevalence of DM, 23.4%. The cut-off points are all the means for continuous data.

Sensitivity analysis

The associations all remained significant after removing any single study conforming to Jackknife sensitivity analysis (see Additional files 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

Publication Bias

There was no evidence of publication bias identified by Egger’s test for all adverse outcomes, with P = 0.205, 0.211, 0.053, 0.568 and 0.365 for all-cause mortality, short-term all-cause mortality, MACE, MACCE and stent restenosis, respectively (see Additional file 10).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study was the first meta-analysis to evaluate the association between CI-AKI and risk of adverse outcomes in ACS patients treated with PCI. Twenty two studies were eligible. We confirmed that CI-AKI might increase 216, 455, 49, 86 and 50% relative risk for all-cause mortality, short-term all-cause mortality, MACE, MACCE, and stent restenosis in ACS patients treated with PCI.

There was moderate heterogeneity among the studies included for all-cause mortality and short-term all-cause mortality, but no heterogeneity among the studies included for MACE, MACCE and stent restenosis.

CI-AKI was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, short-term all-cause mortality, MACE, MACCE and stent restenosis of ACS patients after PCI in our study. Especially for short-term all-cause mortality, the increased risk was up to 455% compared to none CI-AKI patients. According to other reports, in ACS patients treated with PCI, CI-AKI was also associated with other adverse outcomes, including net adverse clinical events (HR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.23–1.9 [19]), major bleeding (HR = 2.69, 95% CI: 2.26–3.2 [24] and HR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.57–2.73 [19]) and in-hospital ischaemic stroke (HR = 2.91, 95% CI: 1.03–8.24 [38]).

The reasons for taking CI-AKI as a strong predictor of clinical adverse outcomes were complex. It was demonstrated that the renal function of 54.6% of CI-AKI patients did not return to baseline level after 2 weeks [39]. CI-AKI patients were at increased risk of progressive decline in kidney function [40, 41]. Over 45% of patients had persistent renal dysfunction leading to chronic kidney disease (CKD) [42]. Patients with CKD have more severe and diffuse coronary artery disease, higher rates of traditional coronary risk factors and complications such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy dyslipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and congestive heart failure [43, 44], and more restrictions to therapies for other diseases [43, 45].

For patients undergoing coronary angiography, CI-AKI was also reported to be associated with an increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes in a meta-analysis [46]. It included 39 studies and showed that CI-AKI was associated with increased risk of mortality (adjusted pooled RR = 2.39, 95% CI: 1.98–2.90), MACE (adjusted pooled RR = 1.98, 95% CI: 1.52–2.59) and end-stage renal disease (pooled crude RR, 15.26, 95% CI: 1.86–125.01) for patients treated with coronary angiography. Our meta-analysis focused on ACS patients treated with PCI. Noteworthy, only one same study [12] was included in both our study and the above study. The occurrence of ACS was more of an emergency and increased risk of short-term mortality associated with CI-AKI was higher (pooled RR 5.55; 95% CI 3.53–8.73). Therefore, CI-AKI should be paid more attention to for ACS patients treated with PCI.

There were some limitations of our meta-analysis. Firstly, the diagnostic criteria for CI-AKI, MACE and MACCE were not completely uniform in all included studies. Secondly, studies included in this meta-analysis were not adjusted for consistent factors when assessing the association between CI-AKI and outcomes. Finally, the differences of demographic and clinical characteristics regarding race, genetics, geographical locations and PCI procedure across the different populations pooled were not thoroughly studied. All the limitations might have effect on the risk evaluation of prognosis.

Conclusions

Our review shows that CI-AKI is associated with increased adverse events. Hence, it will be useful in promptly detecting patients at high risk of CI-AKI, and thereby they can be carefully monitored and treated with adequate prophylactic strategy.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

Acute coronary syndrome

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- CI-AKI:

-

Contrast-induced acute kidney injury

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HLP:

-

Hyperlipidemia

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- HT:

-

Hypertension

- MACCE:

-

Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events

- MACE:

-

Major adverse cardiac events

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa scale

- NSTEMI:

-

Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction

- OR,:

-

Odds ratio

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- STEMI:

-

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

- UA:

-

Unstable angina

References

Takii T, Yasuda S, Takahashi J, Ito K, Shiba N, Shirato K, Shimokawa H. Trends in acute myocardial infarction incidence and mortality over 30 years in Japan: report from the MIYAGI-AMI registry study. Circ J. 2010;74(1):93–100.

Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet (London, England). 2003;361(9351):13–20.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(16):e147–239.

Raber L, Kelbaek H, Ostojic M, Baumbach A, Heg D, Tuller D, von Birgelen C, Roffi M, Moschovitis A, Khattab AA, et al. Effect of biolimus-eluting stents with biodegradable polymer vs bare-metal stents on cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the COMFORTABLE AMI randomized trial. Jama. 2012;308(8):777–87.

Roger VL, Weston SA, Gerber Y, Killian JM, Dunlay SM, Jaffe AS, Bell MR, Kors J, Yawn BP, Jacobsen SJ. Trends in incidence, severity, and outcome of hospitalized myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121(7):863–9.

Kostis WJ, Deng Y, Pantazopoulos JS, Moreyra AE, Kostis JB. Trends in mortality of acute myocardial infarction after discharge from the hospital. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(6):581–9.

McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, Davidson C, Lameire N, Stacul F, Tumlin J. Epidemiology and prognostic implications of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(6a):5k–13k.

McCullough PA. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(15):1419–28.

Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5):930–6.

Shusterman N, Strom BL, Murray TG, Morrison G, West SL, Maislin G. Risk factors and outcome of hospital-acquired acute renal failure. Clinical epidemiologic study. Am J Med. 1987;83(1):65–71.

Dangas G, Iakovou I, Nikolsky E, Aymong ED, Mintz GS, Kipshidze NN, Lansky AJ, Moussa I, Stone GW, Moses JW, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary interventions in relation to chronic kidney disease and hemodynamic variables. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(1):13–9.

Wickenbrock I, Perings C, Maagh P, Quack I, van Bracht M, Prull MW, Plehn G, Trappe HJ, Meissner A. Contrast medium induced nephropathy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndrome: differences in STEMI and NSTEMI. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98(12):765–72.

Akkaya E, Ayhan E, Uyarel H, Ergelen M, Turer A, Demirci D, Demirci D, Cicek G, Gul M, Gunaydin Z, et al. The impact of chronic kidney disease on in-hospital clinical outcomes in patients undergoing primary percutaneous angioplasty for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Turk Kardiyol Dern Ars. 2011;39(4):276–82.

Lucreziotti S, Centola M, Salerno-Uriarte D, Ponticelli G, Battezzati PM, Castini D, Sponzilli C, Lombardi F. Female gender and contrast-induced nephropathy in primary percutaneous intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(1):37–42.

Akin F, Celik O, Altun I, Ayca B, Ozturk D, Satilmis S, Ayaz A, Tasbulak O. Relation of red cell distribution width to contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients undergoing a primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26(4):289–95.

Cicek G, Bozbay M, Acikgoz SK, Altay S, Ugur M, Koroglu B, Uyarel H. The ratio of contrast volume to glomerular filtration rate predicts in-hospital and six-month mortality in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiol J. 2015;22(1):101–7.

Park SH, Jeong MH, Park IH, Choi JS, Rhee JA, Kim IS, Kim MC, Cho JY, Sim DS, Hong YJ, et al. Effects of combination therapy of statin and N-acetylcysteine for the prevention of contrast-induced nephropathy in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2016;212:100–6.

Kume K, Yasuoka Y, Adachi H, Noda Y, Hattori S, Araki R, Kohama Y, Imanaka T, Matsutera R, Kosugi M, et al. Impact of contrast-induced acute kidney injury on outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2013;14(5):253–7.

Narula A, Mehran R, Weisz G, Dangas GD, Yu J, Genereux P, Nikolsky E, Brener SJ, Witzenbichler B, Guagliumi G, et al. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the HORIZONS-AMI substudy. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(23):1533–40.

Nakahashi H, Kosuge M, Sakamaki K, Kiyokuni M, Ebina T, Hibi K, Tsukahara K, Iwahashi N, Kuji S, Oba MS, et al. Combined impact of chronic kidney disease and contrast-induced nephropathy on long-term outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction who undergo primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart vessels. 2017;32(1):22–9.

Wi J, Ko YG, Shin DH, Kim JS, Kim BK, Choi D, Ha JW, Hong MK, Jang Y. Prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy with persistent renal dysfunction and adverse long-term outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction using the Mehran risk score. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(1):46–53.

Watabe H, Sato A, Hoshi T, Takeyasu N, Abe D, Akiyama D, Kakefuda Y, Nishina H, Noguchi Y, Aonuma K. Association of contrast-induced acute kidney injury with long-term cardiovascular events in acute coronary syndrome patients with chronic kidney disease undergoing emergent percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174(1):57–63.

Park SD, Moon J, Kwon SW, Suh YJ, Kim TH, Jang HJ, Suh J, Park HW, Oh PC, Shin SH, et al. Prognostic impact of combined contrast-induced Acute kidney injury and hypoxic liver injury in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous Coronary intervention: results from INTERSTELLAR registry. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159416.

Giacoppo D, Madhavan MV, Baber U, Warren J, Bansilal S, Witzenbichler B, Dangas GD, Kirtane AJ, Xu K, Kornowski R, et al. Impact of contrast-induced Acute kidney injury after percutaneous Coronary intervention on short- and long-term outcomes: pooled analysis from the HORIZONS-AMI and ACUITY trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(8):e002475.

Gungor B, Karatas MB, Ipek G, Ozcan KS, Canga Y, Onuk T, Keskin M, Hayiroglu MI, Karadeniz FO, Sungur A, et al. Association of contrast-induced nephropathy with bare metal stent restenosis in STEMI patients treated with primary PCI. Ren Fail. 2016;38(8):1167–73.

Turan B, Erkol A, Gul M, Findikcioglu U, Erden I. Effect of contrast-induced nephropathy on the long-term outcome of patients with non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Cardiorenal Med. 2015;5(2):116–24.

Kuboyama O, Tokunaga T. The prevalence and prognosis of contrast-induced acute kidney injury according to the definition in patients with acute myocardial infarction who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin Trials Regul Sci Cardiol. 2016;13:29–33.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Walls GA, Shee B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available from http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 15 Mar 2017.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Bmj. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. Jama. 1998;280(19):1690–1.

Sadeghi HM, Stone GW, Grines CL, Mehran R, Dixon SR, Lansky AJ, Fahy M, Cox DA, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, et al. Impact of renal insufficiency in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108(22):2769–75.

Chong E, Shen L, Tan HC, Poh KK. A cohort study of risk factors and clinical outcome predictors for patients presenting with unstable angina and non ST segment elevation myorardial infraction undergoing coronary intervention. Med J Malaysia. 2011;66(3):249–52.

Crimi G, Leonardi S, Costa F, Ariotti S, Tebaldi M, Biscaglia S, Valgimigli M. Incidence, prognostic impact, and optimal definition of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in consecutive patients with stable or unstable coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Insights from the all-comer PRODIGY trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86(1):E19–27.

Centola M, Lucreziotti S, Salerno-Uriarte D, Sponzilli C, Ferrante G, Acquaviva R, Castini D, Spina M, Lombardi F, Cozzolino M, et al. A comparison between two different definitions of contrast-induced acute kidney injury in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2016;210:4–9.

Farhan S, Vogel B, Tentzeris I, Jarai R, Freynhofer MK, Smetana P, Egger F, Kautzky-Willer A, Huber K. Contrast induced acute kidney injury in acute coronary syndrome patients: a single Centre experience. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2016;5(1):55–61.

Uyarel H, Cam N, Ergelen M, Akkaya E, Ayhan E, Isik T, Cicek G, Gunaydin ZY, Osmonov D, Gul M, Demirci D, Guney MR, Ozturk R, Yekeler I. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: incidence, a simple risk score, and prognosis. Arch Med Sci. 2009;5(4):550–8.

Ergelen M, Gorgulu S, Uyarel H, Norgaz T, Ayhan E, Akkaya E, Ergelen R, Cicek G, Ugur M, Soylu O, et al. Ischaemic stroke complicating primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Acta Cardiol. 2009;64(6):729–34.

Brown JR, Malenka DJ, DeVries JT, Robb JF, Jayne JE, Friedman BJ, Hettleman BD, Niles NW, Kaplan AV, Schoolwerth AC, et al. Transient and persistent renal dysfunction are predictors of survival after percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the Dartmouth dynamic registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72(3):347–54.

Amdur RL, Chawla LS, Amodeo S, Kimmel PL, Palant CE. Outcomes following diagnosis of acute renal failure in U.S. veterans: focus on acute tubular necrosis. Kidney Int. 2009;76(10):1089–97.

James MT, Ghali WA, Tonelli M, Faris P, Knudtson ML, Pannu N, Klarenbach SW, Manns BJ, Hemmelgarn BR. Acute kidney injury following coronary angiography is associated with a long-term decline in kidney function. Kidney Int. 2010;78(8):803–9.

Wi J, Ko YG, Kim JS, Kim BK, Choi D, Ha JW, Hong MK, Jang Y. Impact of contrast-induced acute kidney injury with transient or persistent renal dysfunction on long-term outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart. 2011;97(21):1753–7.

Fox CS, Muntner P, Chen AY, Alexander KP, Roe MT, Cannon CP, Saucedo JF, Kontos MC, Wiviott SD, Acute Coronary T, et al. Use of evidence-based therapies in short-term outcomes of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients with chronic kidney disease: a report from the National Cardiovascular Data Acute Coronary Treatment and intervention outcomes network registry. Circulation. 2010;121(3):357–65.

Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC, Coresh J, Culleton B, Hamm LL, McCullough PA, Kasiske BL, Kelepouris E, Klag MJ, et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease: a statement from the American Heart Association councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Circulation. 2003;108(17):2154–69.

Anavekar NS, McMurray JJ, Velazquez EJ, Solomon SD, Kober L, Rouleau JL, White HD, Nordlander R, Maggioni A, Dickstein K, et al. Relation between renal dysfunction and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1285–95.

James MT, Samuel SM, Manning MA, Tonelli M, Ghali WA, Faris P, Knudtson ML, Pannu N, Hemmelgarn BR. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and risk of adverse clinical outcomes after coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(1):37–43.

Wi J, Ko YG, Shin DH, Kim JS, Kim BK, Choi D, et al. Prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy With persistent renal dysfunction and adverse long-term Outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction Using the mehran risk score. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36(1):46-53.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This project was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81470948, 81670633), National key research and development program (Grants 2016YFC0906103) and the National Key Technology R&D Program (Grant 2013BAI09B06, 2015BAI12B07).

Availability of data and materials

All data that support the conclusions of this manuscript are included within the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SWG and GX conceived and designed the study. YY screened the abstract and full text, extracted data, assessed studies and drafted the manuscript. KCG screened the abstract and full text, extracted data, assessed studies and performed statistical analyses. WFS assisted in statistical analyses. RL, YCC, KCG, and YY drafted the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA Checklist (PDF 353 kb)

Additional file 2:

Search strategy to identify studies. (PDF 224 kb)

Additional file 3:

Other related characteristics of included studies. (PDF 204 kb)

Additional file 4:

Adjusted confounders in each included study. (PDF 243 kb)

Additional file 5:

Sensitivity analysis for all-cause mortality. (PDF 106 kb)

Additional file 6:

Sensitivity analysis for short-term all-cause mortality. (PDF 100 kb)

Additional file 7:

Sensitivity analysis for major adverse cardiac events. (PDF 97 kb)

Additional file 8:

Sensitivity analysis for major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. (PDF 96 kb)

Additional file 9:

Sensitivity analysis for stent restenosis. (PDF 92 kb)

Additional file 10:

Egger’s test of all analysis. (PDF 186 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., George, K.C., Luo, R. et al. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and adverse clinical outcomes risk in acute coronary syndrome patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol 19, 374 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-018-1161-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-018-1161-5