Abstract

Background

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition requiring prompt diagnosis and therapeutic intervention. Diagnosis and management of cardiac tamponade in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection pose a major challenge for clinicians. This study aimed to investigate clinical characteristics, paraclinical findings, therapeutic options, patient outcomes, and etiologies of cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV.

Methods

Pubmed, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science databases were systematically searched for case reports or case series reporting HIV-infected patients with cardiac tamponade up to February 29, 2024. Baseline characteristics, clinical manifestations, paraclinical findings, therapeutic options, patient outcomes, and etiologies of cardiac tamponade were independently extracted by two reviewers.

Results

A total of 37 articles reporting 40 HIV-positive patients with cardiac tamponade were included. These patients mainly experienced dyspnea, fever, chest pain, and cough. They were mostly presented with abnormal vital signs, such as tachypnea, tachycardia, fever, and hypotension. Physical examination predominantly revealed elevated Jugular venous pressure (JVP), muffled heart sounds, and palsus paradoxus. Echocardiography mostly indicated pericardial effusion, right ventricular collapse, and right atrial collapse. Most patients underwent pericardiocentesis, while others underwent thoracotomy, pericardiotomy, and pericardiostomy. Furthermore, infections and malignancies were the most common etiologies of cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive patients, respectively. Eventually, 80.55% of the patients survived, while the rest expired.

Conclusion

Infections and malignancies are the most common causes of cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive patients. If these patients demonstrate clinical manifestations of cardiac tamponade, clinicians should conduct echocardiography to diagnose it promptly. They should also undergo pericardial fluid drainage and receive additional therapy, depending on the etiology, to reduce the mortality rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a significant global health concern, impacting millions of individuals worldwide [1]. According to the last report from the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in 2022, 85.6 million individuals have become infected with HIV, leading to 40.4 million deaths over the past four decades [2]. The introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has transformed HIV infection from a terminal illness to a chronic condition, resulting in improved life expectancy for many patients [3]. However, many HIV-positive patients experience HIV-related complications, such as opportunistic infections, metabolic disorders, malignancies, or organ dysfunctions [4, 5]. Cardiac complications have emerged as a prominent concern, contributing to increased morbidity and mortality in people living with HIV [6]. Cardiac involvement in these patients can present as ischemic heart disease, endocarditis, HIV-related cardiac malignancies, pulmonary artery hypertension, cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, pericarditis, constrictive pericarditis, and cardiac tamponade [7].

Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening emergency characterized by dyspnea, tachycardia, hypotension, and pulsus paradoxus. It is essential to promptly diagnose and treat cardiac tamponade to prevent cardiac shock and potential mortality [8, 9]. Performing pericardiocentesis as early as possible to relieve pressure on the heart chambers and prevent hemodynamic compromise is crucial, which can improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of complications associated with delayed treatment [10]. However, when performing therapeutic procedures for cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive patients, there is a risk of transmitting pathogens through blood or body fluids to healthcare workers [11]. This emphasizes the importance of stringent infection control and precautionary measures when managing cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV among healthcare workers. The intersection of HIV infection and cardiac tamponade presents unique challenges in clinical practice, emphasizing the need for evidence-based guidelines to ensure optimal patient care and healthcare worker safety [12].

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate clinical characteristics, paraclinical findings, therapeutic options, patient outcomes, and etiologies of cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV. This information can help clinicians promptly diagnose similar cases and make appropriate therapeutic decisions.

Methods

This study conforms to the “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses” (PRISMA) statement [13]. The study protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews as PROSPERO (CRD42024517212).

Eligibility criteria

In our systematic review, full-text English-language case reports/case series reporting HIV-infected patients with cardiac tamponade were included. Original articles, review articles, randomized controlled trials, animal studies, commentaries, editorials, guidelines, and conference papers were excluded.

Search strategy and information sources

PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Web of Science were systematically searched for eligible articles published between January 1994 and February 29, 2024 using the following search strategy: ((((HIV) OR (human immunodeficiency virus)) OR (AIDS)) OR (acquired immunodeficiency virus)) AND (((cardiac tamponade) OR (pericardial tamponade)) OR (heart tamponade)). Further studies were identified by manually searching all the references in the selected publications.

Study selection

Searching databases yielded records that were merged and duplicate records were removed using EndNote X6 software (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). Initially, records were independently screened by two reviewers regarding the title and abstract (HN and SR). Subsequently, the full texts of those that passed the initial screening were independently assessed for eligibility by the same reviewers (HN and SR). Disagreements were resolved by the principal investigator (AK).

Data extraction

The following variables were independently extracted from the included publications by two reviewers (HN and SR): first author name, publication year, country where the cases lived, age, sex, underlying diseases, treatment for HIV infection, clinical characteristics (signs and symptoms), imaging findings, laboratory results, reports of cardiac paraclinical investigations (electrocardiography and echocardiography), etiologies of cardiac tamponade and how to treat them, and patients outcome. Disagreements were resolved by the principal investigator (AK).

Quality assessment

The checklist provided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) was used to perform the quality assessment of case reports and case series [14].

Results

Study selection

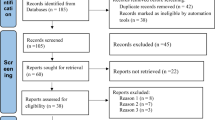

After removing duplicates from 1427 records obtained from the database search, 1108 of them screened regarding title and abstract. Subsequently, full texts of the remaining records were assessed for eligibility, and 37 studies were included for systematic review. Figure 1 depicts the flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review.

The detailed characteristics of the included studies are illustrated in Table 1. In this systematic review, 35 case reports and 2 case series reporting 40 HIV-positive patients with cardiac tamponade (31 men and 9 women) were examined.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

Table 2 presents the clinical characteristics of the patients. The most common underlying diseases were Kaposi’s sarcoma (4/18, 22.22%), hepatitis B (3/18, 16.67%), tuberculosis (2/18, 11.11%), syphilis (2/18, 11.11%), and hypertension (2/18, 11.11%). They mainly experienced dyspnea (32/38, 84.21%), fever (19/38, 50.00%), chest pain (17/38, 44.73%), and cough (15/38, 39.47%). They were mostly presented with abnormal vital signs, such as tachypnea (20/21, 95.23%), tachycardia (25/33, 75.75%), fever (13/26, 50.00%), and hypotension (10/31, 32.25%). Physical examination predominantly revealed elevated Jugular venous pressure (JVP) (27/30, 90.00%), muffled heart sounds (19/29, 65.51%), and palsus paradoxus (15/31, 48.38%).

Paraclinical findings of the patients

Table 3 shows the paraclinical findings of the patients. The majority of patients had a CD4 < 200 cell/mm3 (16/27, 59.25%) than CD4 > 200 cell/mm3 (11/27, 40.75%), and more patients had detectable viral loads (9/13, 69.23%) than undetectable ones (4/13, 30.77%). Leukocytosis (8/21, 38.10%) and normal white blood cell (WBC) count (8/21, 38.10%) were more common than leukopenia (5/21, 23.80%). Normal platelet count (7/11, 63.63%) was more common than thrombocytopenia (4/11, 36.37%). Furthermore, most patients exhibited elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (9/10, 90.00%) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (6/7, 85.71%).

The most common electrocardiographic finding was sinus tachycardia (8/16, 50.00%), followed by low voltage QRS complex (7/16, 43.75%), ST elevation in inferior leads (3/16, 18.75%), diffuse ST elevation and PR depression (3/16, 18.75%), inverted T in inferior leads (3/16, 18.75%). Echocardiography mostly revealed pericardial effusion (38/38, 100%), right ventricular collapse (20/38, 52.63%), and right atrial collapse (12/38, 31.57%). In addition, the most evident findings on chest imaging were pleural effusion (20/39, 51.28%), enlarged cardiac silhouette sign (15/39, 38.46%), cardiomegaly (14/39, 35.89%), pulmonary consolidation (11/39, 28.20%), and pericardial effusion (11/39, 28.20%).

Therapeutic options and outcomes of the patients

Table 4 demonstrates the therapeutic options and outcomes of the patients. Most patients underwent pericardiocentesis (34/39, 87.17%), while others underwent thoracotomy (4/39, 10.25%), pericardiotomy (3/39, 7.69%), and pericardiostomy (2/39, 5.12%). Table S1 displays results of pericardial fluid analysis of the patients. Furthermore, most patients survived (29/36, 80.55%), while the rest expired (7/39, 19.45%).

Etiologies of cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive patients

Table 5 summarizes the etiologies of cardiac tamponade. According to our systematic review, infections (25/40, 62.50%), malignancies (12/40, 30.0%), and systemic diseases (2/40, 5.00%) were the most common etiologies of cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive patients, respectively. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (6/25, 24.00%), Nocardia species (5/25, 20.00%), multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (3/25, 12.00%), and Streptococcus pneumonia (2/25, 8.00%) were the most common infectious etiologies, respectively. Moreover, Kaposi’s sarcoma (4/12, 33.34%), Burkitt lymphoma (3/12, 25.00%), and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (2/12, 16.67%) were the most common malignant etiologies, respectively. Additionally, HIV-associated immune complex kidney disease (1/40, 2.50%) and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (1/40, 2.50%) were two systemic diseases that caused cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV.

Discussion

This study was conducted to provide more information regarding cardiac tamponade in patients with HIV infection. The annual incidence of cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV is estimated to be about 1%. However, it can increase up to 9% in cases with pericardial effusion [15]. Patients with pericardial effusion have lower CD4 counts compared to those without pericardial effusion, indicating advanced HIV infection [7]. The findings of our systematic review demonstrated that cardiac tamponade predominantly occurred in men aged 20 to 40 years, possibly due to the demographic distribution of HIV infection, which was more prevalent in young males.

The diagnosis of cardiac tamponade is established by clinical suspicion and confirmation by echocardiography [10]. HIV-infected patients with cardiac tamponade may experience dyspnea, chest pain, fever, or other symptoms, depending on the disease etiology [16]. In most cases with cardiac tamponade, physical examination reveals evidence of increased systemic venous pressure, tachycardia, tachypnea, and pulsus paradoxus, which is consistent with our results. Nevertheless, systemic blood pressure may be normal, decreased, or even elevated [10]. Moreover, evidence of friction rub or muffled heart sounds may be found [16]. Upon electrocardiography, sinus tachycardia, low voltage QRS complex, ST or T changes, and electrical alternans may be found [17], which is in line with our findings. Our results indicated that pericardial effusion, right ventricular collapse, and right atrial collapse were frequently observed in the echocardiography of cardiac tamponade cases. Based on a review article by Fowler, massive peripheral effusion, diastolic compression of the right ventricle or right atrium, abnormal respiratory alterations in ventricular dimensions, flow velocities of the atrioventricular valves, and the inferior vena cava (IVC) plethora, are indicators of cardiac tamponade in echocardiography [18].

Laboratory results and imaging findings play a crucial role in diagnosing the etiology of cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV. For instance, elevated inflammatory markers (e.g., leukocytosis, and elevated ESR & CRP) may indicate the infectious etiology of cardiac tamponade [19]. Additionally, certain imaging findings such as mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy, parenchymal consolidations, cavitary lesions, pleural effusion, miliary pattern, and centrilobular nodules point towards pulmonary tuberculosis as the potential etiology. It is important to note that in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, cardiac tamponade may result from mycobacterial invasion into the cardiac tissue [20].

According to our findings, the most common etiologies of cardiac tamponade were infectious (Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Nocardia species, Staphylococcus aureus) and malignant (Kaposi’s sarcoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and diffuse large B cell lymphoma) conditions, which align with existing literature [17, 21]. According to a systematic review by Gowda et al., the majority of cardiac tamponades in HIV-positive patients were attributed to Mycobacterium species (42.1%). Malignancies were the second leading cause of HIV-related cardiac tamponade (16.1%), including lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, and adenocarcinoma. Bacterial causes accounted for 10.6% of cases, with Staphylococcus aureus being the most common agent, followed by Streptococcus species, Klebsiella pneumonia, Rhodococcus equi, Pseudomonas aeroginosa, and Listeria monocytogenes. Furthermore, fungal (Cryptococcus neoformans, Nocardia asteroids, and Aspergillus species) and viral (Cytomegalovirus and Herpes simplex virus) etiologies were also identified [17].

Overall, the evaluation of pericardial effusion/cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV involves the following steps. Firstly, clinicians should suspect pericardial effusion/cardiac tamponade based on symptoms and signs. Secondly, they should carry out comprehensive diagnostic measures to evaluate the extent of pericardial effusion and subsequent hemodynamic compromise. Thirdly, they should make therapeutic decisions based on the benefits and risks of pericardiocentesis and closely monitor the patient’s response [10, 22, 23].

Therefore, unexplained dyspnea, Beck’s triad (hypotension, elevated JVP, and muffled heart sounds), or cardiomegaly on chest imaging in people living with HIV should rapidly be evaluated using echocardiography. If cardiac tamponade is confirmed, it is necessary to perform pericardiocentesis to drain effusions and stabilize vital signs of the patient [24]. In case of massive effusion, reaccumulation of pericardial fluid, or the need for tissue biopsy, more aggressive interventions such as pericardiostomy or thoracotomy may be required [21]. It is important to be alert that during therapeutic procedures for cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive individuals, there is a risk of transmitting the virus from the patient to healthcare workers. Thus, clinicians should take appropriate precautions to prevent the transmission of HIV when managing cardiac tamponade [11]. Our systematic review revealed that the majority of HIV-positive patients with cardiac tamponade underwent pericardiocentesis as the primary therapeutic option. However, a few patients underwent secondary procedures for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. For instance, some patients had a thoracotomy to obtain biopsies. Pericardiostomy and pericardiotomy were performed in cases where the primary pericardiocentesis did not have the desired effect.

A study by Kwan et al. reported that 54% of HIV-positive patients with cardiac tamponade expired on discharge [25]. However, our systematic review indicated that 80.55% of cases survived after receiving appropriate therapy. This discrepancy in survival rate may be influenced by changes in healthcare facilities over time. In recent years, improved access to medical facilities and advancements in medical care have led to earlier diagnosis and timely treatment of cardiac tamponade, resulting in a lower mortality rate. There is ongoing debate regarding whether the type of therapeutic procedure is linked to the mortality rate. A study by Flum et al. reported that pericardiostomy performed under general anesthesia was associated with high mortality rates [26], while another study reported that pericardiostomy under local anesthesia was safer. Additionally, the mortality rate may be influenced by the progression of HIV infection and its complications rather than solely by the therapeutic procedures used to treat cardiac tamponade [21].

Our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. Although reviewing multiple databases with appropriate queries, some relevant articles might be unintentionally missed. We included publications written in English, which could lead to a language bias. Additionally, the included records reported patient outcomes as either survived or expired, which means that no prolonged follow-ups were available to assess the recurrence rate of cardiac tamponade. Given the rarity of cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV, we had to include only case reports/case series in the systematic review. Therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings from these limited cases.

Conclusion

Infections and malignancies are the most common causes of cardiac tamponade in HIV-positive patients. If these patients demonstrate clinical manifestations of cardiac tamponade, clinicians should conduct echocardiography to diagnose it promptly. They should also undergo pericardial fluid drainage and receive additional therapy, depending on the etiology, to reduce the mortality rate.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Global regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and, mortality of HIV. 1980–2017, and forecasts to 2030, for 195 countries and territories: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study 2017. The lancet HIV. 2019;6(12):e831-e59.

UNAIDS, Global HIV. & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet 2021 [15 March 2024]. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, Hernández-Díaz S, Robins JM, Sabin C, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24(1):123–37.

Khunnawat C, Mukerji S, Havlichek D Jr., Touma R, Abela GS. Cardiovascular manifestations in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(5):635–42.

Zaid D, Greenman Y. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and the Endocrine System. Endocrinol Metabolism (Seoul Korea). 2019;34(2):95–105.

Pinto DSM, da Silva M. Cardiovascular Disease in the setting of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2018;14(1):25–41.

Chastain DB, King TS, Stover KR. Infectious and non-infectious etiologies of Cardiovascular Disease in Human Immunodeficiency Virus infection. open AIDS J. 2016;10:113–26.

Farouji I, Damati A, Chan KH, Ramahi A, Chenitz K, Slim J, et al. Cardiac Tamponade Associated with Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Immune Complex kidney disease. J Global Infect Dis. 2021;13(3):151–3.

Estok L, Wallach F. Cardiac tamponade in a patient with AIDS: a review of pericardial disease in patients with HIV infection. Mt Sinai J Med. 1998;65(1):33–9.

Imazio M, Adler Y. Management of pericardial effusion. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(16):1186–97.

Bouya S, Balouchi A, Rafiemanesh H, Amirshahi M, Dastres M, Moghadam MP, et al. Global prevalence and Device Related Causes of Needle Stick Injuries among Health Care workers: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Annals Global Health. 2020;86(1):35.

Riddler SA, Haubrich R, DiRienzo AG, Peeples L, Powderly WG, Klingman KL, et al. Class-sparing regimens for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(20):2095–106.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg (London England). 2010;8(5):336–41.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53.

Heidenreich PA, Eisenberg MJ, Kee LL, Somelofski CA, Hollander H, Schiller NB, et al. Pericardial effusion in AIDS. Incidence and survival. Circulation. 1995;92(11):3229–34.

Barbaro G, Fisher SD, Giancaspro G, Lipshultz SE. HIV-associated cardiovascular complications: a new challenge for emergency physicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(7):566–74.

Gowda RM, Khan IA, Mehta NJ, Gowda MR, Sacchi TJ, Vasavada BC. Cardiac tamponade in patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. Angiology. 2003;54(4):469–74.

Fowler NO. Cardiac tamponade. A clinical or an echocardiographic diagnosis? Circulation. 1993;87(5):1738–41.

Furqan MM, Verma BR, Cremer PC, Imazio M, Klein AL. Pericardial diseases in COVID19: a contemporary review. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23(7):90.

Nachiappan AC, Rahbar K, Shi X, Guy ES, Mortani Barbosa EJ Jr., Shroff GS, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis: role of Radiology in diagnosis and management. Radiographics: Rev Publication Radiological Soc North Am Inc. 2017;37(1):52–72.

Chen Y, Brennessel D, Walters J, Johnson M, Rosner F, Raza M. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated pericardial effusion: report of 40 cases and review of the literature. Am Heart J. 1999;137(3):516–21.

Adler Y, Ristić AD, Imazio M, Brucato A, Pankuweit S, Burazor I, et al. Cardiac tamponade. Nat Reviews Disease Primers. 2023;9(1):36.

Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; the Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European society of cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(7):587–610.

Harmon WG, Dadlani GH, Fisher SD, Lipshultz SE. Myocardial and Pericardial Disease in HIV. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2002;4(6):497–509.

Kwan T, Karve MM, Emerole O. Cardiac tamponade in patients infected with HIV. A report from an inner-city hospital. Chest. 1993;104(4):1059–62.

Flum DR, McGinn JT Jr., Tyras DH. The role of the ‘pericardial window’ in AIDS. Chest. 1995;107(6):1522–5.

Aboulafia DM, Bush R, Picozzi VJ. Cardiac tamponade due to primary pericardial lymphoma in a patient with AIDS. Chest. 1994;106(4):1295–9.

Legras A, Lemmens B, Dequin PF, Cattier B, Besnier JM. Tamponade due to Rhodococcus equi in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Chest. 1994;106(4):1278–9.

Scerpella EG, Fatmi AA, Brito MA. Bacterial pericarditis and cardiac tamponade in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1: case report and review. Clin Infect Diseases: Official Publication Infect Dis Soc Am. 1995;21(6):1518–9.

Serrano-Heranz R, Camino A, Vilacosta I, López-Castellanos A, Roca V. Tuberculous cardiac tamponade and AIDS. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(3):430–2.

Van Vooren JP, Renard M, Dargent JL, Capel P, Feremans WW, Farber CM. Cardiac tamponade: the first manifestation of a generalized lymphoma in a patient with HIV infection. Eur J Haematol. 1995;55(4):274.

Bennis A, Mehadji B, Nourredine M, Haddani J, Soulami S, Chraibi N. Cardiac tamponade as the first manifestation of AIDS. Eur Heart J. 1996;17(11):1771–2.

Vijay V, Aloor RK, Yalla SM, Bebawi M, Kashan F. Pericardial tamponade from Kaposi’s sarcoma: role of early pericardial window. Am Heart J. 1996;132(4):897–9.

Currie PF, Wright RA, Campanella C, Gray J, Boon NA. Long-term survival following pericardiectomy for Staphylococcus aureus pericarditis in an HIV-positive drug user. Eur Heart J. 1997;18(3):526–7.

Azrak EC, Kern MJ, Bach RG. Hemodynamics of cardiac tamponade in a patient with AIDS-related non-hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998;45(3):287–91.

Chyu KY, Birnbaum Y, Naqvi T, Fishbein MC, Siegel RJ. Echocardiographic detection of Kaposi’s sarcoma causing cardiac tamponade in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Cardiol. 1998;21(2):131–3.

Rivero A, Esteve A, Santos J, Maŕquez M. Cardiac tamponade caused by Nocardia asteroides in an HIV-infected patient. J Infect. 2000;40(2):206–7.

Theodossiades G, Tsevrenis V, Bellia M, Avgeropoulou A, Nomikos J, Kontopoulou-Griva I. Cardiac tamponade due to post-cardiac injury syndrome in a patient with severe haemophilia A and HIV-1 infection. Haemophilia: Official J World Federation Hemophilia. 2000;6(5):584–7.

Goldberg L, Hagios P, Grigorov V, Mekel J. Low pressure left ventricular tamponade in a patient with rheumatic mitral stenosis and HIV-related acute pericarditis. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2003;14(2):91–4.

Leang B, Lynen L, Lim K, Jacques G, Van Esbroeck M, Zolfo M. Disseminated nocardiosis presenting with cardiac tamponade in an HIV patient. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(12):839–40.

Louw A, Tikly M. Purulent pericarditis due to co-infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a patient with features of advanced HIV infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:12.

Russell JB, Syed FF, Ntsekhe M, Mayosi BM, Moosa S, Tshifularo M, et al. Tuberculous effusive-constrictive pericarditis. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2008;19(4):200–1.

Chandrashekar UK, Acharya V, Gnanadev NC, Varghese GK, Chawla K. Pulmonary nocardiosis presenting with cardiac tamponade and bilateral pleural effusion in a HIV patient. Trop Doct. 2009;39(3):184–6.

Heller T, Lessells RJ, Wallrauch C, Brunetti E. Tuberculosis pericarditis with cardiac tamponade: management in the resource-limited setting. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(6):1311–4.

Park YI, Sir JJ, Park SW, Kim HT, Lee B, Kwak YK, et al. Acute idiopathic hemorrhagic pericarditis with cardiac tamponade as the initial presentation of acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51(2):273–5.

Kabangila R, Mahalu W, Masalu N, Jaka H, Peck R, Recurrent. Massive Kaposi’s Sarcoma Pericardial Effusion presenting without cutaneous lesions in an HIV Infected Adult: a Case Report. Tanzan J Health Res. 2011;13(1):82–6.

Aisenberg GM, y, Martin RME. Pericardial tamponade caused by Nocardia asteroides in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: would sulfa prophylaxis have spared this infection? Infectious Diseases in Clinical Practice. 2014;22(4):e34-e6.

Tsao Y-T, Chen J-C, Tsai W-C. Cardiac tamponade caused by paradoxical immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(11):1712. e1-. e17122.

Laksananun N, Salee P, Kaewpoowat Q. Nocardia beijingensis pericarditis presenting with cardiac tamponade: a case report. Int J STD AIDS. 2018;29(5):515–9.

Luis BAL, Leon-Tavares DM. Purulent pneumococcal pericarditis: an uncommon presentation in the vaccination era. Am J Med. 2018;131(8):e331–2.

Qureshi IA, Zul-Farah S, Carbajal L, Chang A. 33‐year‐old HIV‐positive patient presenting with primary effusion lymphoma. Clin Case Rep. 2018;6(11):2289–90.

Lamas ES, Bononi RJR, Bernardes M, Pasin JL, Soriano HAD, Martucci HT, et al. Acute purulent pericarditis due co-infection with Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis as first manifestation of HIV infection. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2019;2019(2):omy127.

Ali L, Ghazzal A, Sallam T, Cuneo B. Rapidly developing Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Pericarditis and Pericardial Tamponade. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e8001.

Khaba MC, Kampetu MF, Rangaka MC, Karodia M, Ramoroko SP, Madzhia EI. Primary cardiac lymphoma in HIV infected patients: A clinicopathological report of two cases. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2021;69:102757.

Sinit RB, Leung JH, Hwang WS, Woo JS, Aboulafia DM. An unusual case of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis presenting as Impending Cardiac Tamponade in a patient with acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Am J case Rep. 2021;22:e929249.

Chlilek A, Barbar S-D, Stephan R, Barbuat C, Cayla G, Taha M-K et al. First case of invasive meningococcal disease-induced myopericarditis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Intern Med J. 2021:136–7.

Jacobs K, Beringer C, Abdulla SM, Mahomed Z. Massive purulent pericardial effusion with ultrasound features of tamponade secondary to non-typhoid Salmonella infection. BMJ case Rep. 2022;15(2).

Yanes RR, Malijan GMB, Escora-Garcia LK, Ricafrente SAM, Salazar MJ, Suzuki S, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 and HHV-8 from a large pericardial effusion in an HIV-positive patient with COVID-19 and clinically diagnosed Kaposi sarcoma: a case report. Trop Med Health. 2022;50(1):72.

Chang CY, Lee JL, Ong EL. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma presenting with cardiac tamponade in a patient with retroviral disease. Oxf Med Case Rep. 2022;2022(7):omac052.

Rathore A, Patel F, Gupta N, Asiimwe DD, Rollini F, Ravi M. First case of Arcobacter species isolated in pericardial fluid in an HIV and COVID-19 patient with worsening cardiac tamponade. IDCases. 2023;32:e01771.

Sufryd A, Kubicius A, Mizia-Stec K, Wybraniec MT. Acute purulent pericarditis complicated by cardiac tamponade in a human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. Kardiologia Polska. 2024;82(2):220–221.

Yan CL, Zarrabian B, Rodriguez BR, Khandaker M, Radfar A, Lesmes JA, et al. Primary Cardiac Lymphoma in a patient with Well-Controlled Human Immunodeficiency Virus. CASE. 2023;7(2):58–62.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine Research Center at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AK conceptualized the study, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, and critically edited the manuscript. HN collected the data, extracted the data, and wrote the primary draft of the manuscript. SR collected the data, extracted the data, and wrote the primary draft of the manuscript. ST supervised the study, interpreted the data, and critically edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keyvanfar, A., Najafiarab, H., Ramezani, S. et al. Cardiac tamponade in people living with HIV: a systematic review of case reports and case series. BMC Infect Dis 24, 882 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09773-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-024-09773-4