Abstract

Background

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly transmittable virus which causes the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Monocyte distribution width (MDW) is an in-vitro hematological parameter which describes the changes in monocyte size distribution and can indicate progression from localized infection to systemic infection. In this study we evaluated the correlation between the laboratory parameters and available clinical data in different quartiles of MDW to predict the progression and severity of COVID-19 infection.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of clinical data collected in the Emergency Department of Rashid Hospital Trauma Center-DHA from adult individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 between January and June 2020. The patients (n = 2454) were assigned into quartiles based on their MDW value on admission. The four groups were analyzed to determine if MDW was an indicator to identify patients who are at increased risk for progression to sepsis.

Results

Our data showed a significant positive correlation between MDW and various laboratory parameters associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study also revealed that MDW ≥ 24.685 has a strong correlation with poor prognosis of COVID-19.

Conclusions

Monitoring of monocytes provides a window into the systemic inflammation caused by infection and can aid in evaluating the progression and severity of COVID-19 infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly transmittable virus which causes the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) that has affected over 131 million people worldwide and has caused 2.85 million deaths globally as of April 5th, 2021. The most common clinical presentation of this disease includes fever, dry cough and fatigue. However, in a subset of COVID-19 patients, severe outcomes such as viral sepsis are seen. Sepsis is a life-threatening systemic illness which can result in dysregulated immune responses leading to organ dysfunction and a leading cause of mortality [1].

To date, several biomarkers have been identified as early markers to evaluate inflammation and disease outcomes such as C-reactive protein, creatinine and D-dimer [2]. In response to infection, the first immune cells to be recruited are neutrophils and monocytes. In fact, monocyte distribution width (MDW) is used as a biomarker for sepsis where levels > 20 are indicative of sepsis [3]. MDW is an in-vitro hematological parameter which describes the changes in monocyte size distribution and can indicate progression from localized infection to systemic infection [4]. This parameter can be performed along with other routine parameters on several Beckman Coulter DxH analyzers. MDW alone or in combination with white blood count (WBC) can be used to detect early sepsis in the emergency department [5]. A recent study showed that combining MDW ≥ 20 and Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) < 3.2 is more efficient in identifying COVID-19 and can be actually used to distinguish SARS-CoV-2 infection from influenza infection and other upper respiratory tract infections [6]. Monitoring of monocytes provides a window into the systemic inflammation caused by infection and can aid in evaluating the progression and severity of the infection.

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical and biological characteristics of the COVID-19 infected patients and investigated the ability of MDW to predict at an earlier time the disease severity, in comparison with other biomarkers. We also investigated the correlation between routine laboratory parameters in different quartiles of MDW values to evaluate the usefulness of this value in predicting disease outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

This is a retrospective cohort study, which includes all adult individuals (≥ 18 years old) tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the Emergency Department—Rashid Hospital Trauma Center of DHA between January and June 2020. We included only the laboratory-confirmed cases, as the diagnosis was performed by real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) conducted on a nasopharyngeal swab of the patient according to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidance.

Epidemiological characteristics including demographics, recent exposure history, clinical symptoms and signs, and laboratory findings, were obtained from the patients’ electronic medical records in DHA unified electronic system Salama using a standardized data collection form, which is a modified version of the WHO/International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium case record form for severe acute respiratory infections (Additional file 1: Appendix 1).

Clinical and laboratory data

In terms of epidemiological information, we considered patient demographic characteristics including age and gender; clinical symptoms including fever, cough, respiratory symptom, ear, nose and throat symptom; comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, and other disease.

Venous blood samples and nasal-pharyngeal swabs were collected and examined by the Emergency Department Laboratory of Rashid Hospital Trauma Center of DHA. Initial investigations included hematological analysis (complete blood count and coagulation profile), serum biochemical test (renal and liver function, creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, electrolytes, and serum ferritin) in addition to some inflammatory markers (procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein). Frequency of examinations was determined according to the disease progress. For hospitalized patients, nasopharyngeal swab specimens were obtained for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR re-examination every other day after clinical remission of symptoms, including fever, cough, and dyspnea. Repeat RT-PCR tests were performed for SARS-CoV-2 done in patients confirmed to have COVID-19 infection to show viral clearance before hospital discharge or discontinuation of isolation as per national guidelines at the time of this study.

The MDW, which was measured in this study using Beckman Coulter DxH 900 analyzer, is an additional parameter that was recorded in the data collection form. MDW values were compared among the studied groups to determine its usefulness as an indicator to identify patients who are at increased risk for progression to sepsis.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency (number and percentage; %) for categorical variables. For all statistical analyses and tests, SPSS was used (Released 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). The normality test for all groups was done by Shapiro–Wilk tests using SPSS, and sig. of all independent variables > 0.05 means that all groups were normally distributed. To assess the differences between COVID-19 patients different groups based on MDW, ANOVA: analysis of variance used to identify and compare variances among groups for the continuous variables and Chi-square test was used for the categorical variables. P value < 0.05 had been considered significant.

Results

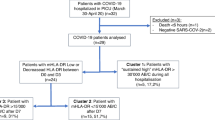

From January to June 2020, 2899 patients were tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 in the Emergency Department of Rashid Hospital Trauma Center of DHA. Only positive COVID-19 patients who had no comorbidities were selected for further analysis (n = 2454) as demonstrated in Fig. 1. The age range was 72 (18–90) years, and 78.7% were men. Further characteristics of the studied population are summarized in Table 1.

As presented in Table 2, the correlation between MDW and major hematology laboratory markers used routinely in assessing cases of COVID-19 in an emergency department setting. Pearson Correlation between MDW and all blood results for all patients included in the study (n = 2454) showed that MDW was positively correlated with WBC (r = 0.101, p < 0.001), neutrophils percentage (NE%) (r = 0.250, p < 0.001), neutrophils count (NE#) (r = 0.162, p < 0.001). Nevertheless, significant negative correlation was observed between MDW and total platelet (PLT) (r = − 0.140, p < 0.001), lymphocytes percentage (LY%) (r = − 0.168, p < 0.001), and monocytes percentage (MO%) (r = − 0.262, p < 0.001).

The results of the current study indicated significant positive correlation between MDW and COVID inflammation markers including C-reactive protein (CRP) (r = 0.401, p < 0.001), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (r = 0.381, p < 0.001), Ferritin (r = 0.305, p < 0.001), and Procalcitonin (r = 0.133, p < 0.001) as shown in Table 3. Interestingly, MDW was significantly correlated with the prothrombin time (PT) (r = 0.174, p < 0.001), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) (r = 0.204, p < 0.001), and D-Dimer (r = − 0.218, p < 0.001) but there was no correlation between MDW and fibrinogen level and Troponin (Table 4). Additionally, MDW was positively correlated with liver enzymes, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (r = 0.091, p < 0.001), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (r = 0.115, p < 0.001), and Total Bilirubin (r = 0. 109, p < 0.001). The only negative correlation was between MDW and Serum albumin r = − 0. 322, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Based on the MDW value, the patients were divided into quartiles with approximately equal numbers of patients assigned to each of the four groups as follows: Q1 (MDW < 21.215, n = 614), Q2 (MDW = 21.215–22.535, n = 614), Q3 (MDW = 22.535–24.685, n = 614) and Q4(MDW ≥ 24.685, n = 614) (Fig. 1). Comparing the different blood biomarkers in each MDW quartile showed that patients with MDW ≥ 24.685 (Q4) demonstrated a strong correlation with poor prognosis COVID-19 related biomarkers. Such patients showed significantly lower platelet counts (Q1 = 240.65 ± 101.408, Q2 = 236.4 ± 96.429, Q3 = 223.53 ± 82.662 and Q4 = 210.24 ± 84.356, p < 0.001) and higher neutrophils percentage (Q1 = 66.449 ± 12.8279, Q2 = 67.864 ± 12.6981, Q3 = 70.98 ± 11.8736 and Q4 = 74.946 ± 13.0348, p < 0.001). Likewise, Q4 patients showed lower lymphocytes percentage (Q1 = 21.301 ± 10.9329, Q2 = 19.717 ± 10.5829, Q3 = 18.373 ± 10.0544 and Q4 = 16.284 ± 10.2825, p < 0.001) and monocytes percentage (Q1 = 10.489 ± 4.0981, Q2 = 10.815 ± 4.2217, Q3 = 9.732 ± 4.1094 and Q4 = 8.019 ± 4.307, p < 0.001). Apparently, the results revealed that all inflammatory markers and risk to develop coagulations markers were significantly higher in Q4 patients compared to the rest of patients in different quartiles (Table 6).

Discussion

In contrast to the delayed neutrophil response specially in viral infections, circulating monocytes are first responders in a proportional magnitude that match to the intensity of microbial exposure [3]. Blood monocytes are transient stage between site of production and site of action during infection, therefore, assessing monocyte activation by MDW can be a direct measure of the level and stage of infection [7]. MDW is a morphometric biomarker in the course of sepsis development and can be an early indicator of sepsis. Recent studies showed that adding MDW to WBC can enhance medical decision making during early sepsis management especially in neonates patients and whenever monitoring sepsis biomarkers is not accessible due to various reasons such as high coast or testing cannot be done for every suspected cases as in pandemics [5, 8]. Our data showed a significant positive correlation between MDW and various laboratory parameters linked with poor prognosis of COVID-19 including total WBC, neutrophils, liver enzymes and inflammatory markers such as CRP. Furthermore, our data revealed that MDW ≥ 24.685 has a strong correlation with poor prognosis of COVID-19.

A negative correlation between MDW and lymphocytes was noted in the current study which is consistent with several studies’ observations that severe illness is associated with lower lymphocyte counts and may predict poor outcomes and higher rate of mortality in patients with COVID‐19 [9,10,11]. Studies on SARS suggested that SARS-CoV-2 exhaust and eliminate natural killer cells and T cells leading to lymphopenia, making lymphopenia a useful predictor for prognosis in the patients as Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admitted patients show a dramatic decrease in T cells, especially CD8-T cell counts [12, 13]. Lymphocyte/monocyte count was found to be the main markers discriminating high- and low-risk groups in COVID-19 patients [14]. We found that peripheral blood from deceased patients with COVID-19 frequently showed neutrophilic leukocytosis and lymphopenia that makes serial white blood cell count and lymphocyte count a useful predictors of progression towards a more severe form of COVID-19 as documented by other studies [15, 16]. Additionally, elevated neutrophil counts were significantly correlated to the mortality of COVID‐19 patients, so combined admission lymphopenia and neutrophilia are associated with poor outcomes in patients with COVID-19 [17, 18].

In all cases, the demonstrated correlation between MDW and poor prognostic WBC, neutrophils and lymphocytes is not surprising as previous studies suggested that circulating monocytes and tissue macrophages participate in all stages of SARS COVID-19 [7]. SARS-CoV-2 can infect monocytes through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2(ACE2)-dependent and independent pathways and shifts in monocyte subpopulations in mediating severity of the disease has been proposed [19, 20]. Certain subsets were disturbed and cells co-expressing markers of M1 and M2 monocytes were found in intermediate and non-classical subsets [21]. Those overactivated monocytes play a role in the cytokine storm that leads to the acute pulmonary injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in COVID‐19 patients [22]. Initially in COVID-19 patients there may be monocytopaenia that is corrected on the 5th day onwards with abnormal activated monocytes characterized by marked anisocytosis, cytoplasmic vacuolisation and paucity of granules [23]. Monocytes in COVID-19 patients have increased lipid droplets accumulation leading to changes in MDW and making this a clinically attractive biomarker for macrophage abnormalities, and structural functional correlation [24].

In our study, MDW was significantly positively correlated with COVID-19 inflammatory markers including CRP, LDH, Ferritin, and Procalcitonin. The level of plasma CRP is known to positively correlate with the severity of COVID-19 pneumonia and can serve as an earlier indicator for severe illness and provides easy guidance to primary care enabling effective intervention measures ahead of time to reduce the rates of severe illness and mortality [25,26,27]. It is well known that systemic inflammation associated with elevated plasma CRP conferred a phenotype on Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMC), specifically through monocyte tissue factor (TF) expression by monocytes/macrophages leads to thrombin generation linked to sepsis [28, 29]. Moreover, it was reported that monocytes can transport CRP in blood flow through monocyte-derived exosomes to maintain chronic inflammation [30].

The findings of the current study presented significant negative correlation between MDW and total platelet (r = − 0.140, p < 0.001). These findings are concurrent with the fact that COVID-19 is associated with mild thrombocytopenia that is linked with more severe disease and mortality as SARS-CoV-2 can alter platelet number, form, and function [31, 32]. Also, MDW was significantly correlated with the prothrombin time (PT) (r = 0.174, p < 0.001), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) (r = 0.204, p < 0.001), and D-Dimer (r = − 0.218, p < 0.001). Studies have reported disturbed coagulation in COVID-19 patients, including decreased antithrombin, prolonged prothrombin time, and increased fibrin degradation products such as D-dimer [33, 34]. This implies increased risk of bleeding, as well as thromboembolic disease that could dispose to the most serious cases including the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [35]. Additionally, D-dimer level at presentation with COVID-19 was shown to predict ICU admission [36].

This study has limitation for being a single-institution study and focused on adults COVID-19 patients. Nevertheless, the interesting about the study is the investigation, for the first time, the correlation between routine laboratory parameters in different quartiles of MDW values and the use of large sample size to support the findings precision. The MDW correlation with different inflammation markers involved in the cytokine storm induced by SARS-CoV-2, such as Interlukin-6 (IL6) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF), is a focal point for future research to increase our understanding of the MDW as a novel sepsis indicator in COVID-19 patients. Further study to investigate the MDW relationship with the clinical evolution of the patients is suggested to make the prognostic value of MDW in disease progress.

Conclusions

To conclude, MDW can be predictor of poor outcome in patients presenting to the emergency setting with COVID-19. Interventions and specific therapeutics to target macrophage activation may be useful in mitigating adverse outcomes in these populations and manage the inflammatory response in COVID-19, preventing progressing to sepsis and multiorgan failure.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they form a part of the patients’ medical record at DHA but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MBRU:

-

Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences

- DHA:

-

Dubai Health Authority

- DSREC:

-

Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee

References

Olwal CO, et al. Parallels in sepsis and COVID-19 conditions: implications for managing severe COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:602848.

Malik P, et al. Biomarkers and outcomes of COVID-19 hospitalisations: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020;26(3):107–8.

Crouser ED, et al. Improved early detection of sepsis in the ED with a novel monocyte distribution width biomarker. Chest. 2017;152(3):518–26.

Crouser ED, et al. Monocyte distribution width enhances early sepsis detection in the emergency department beyond SIRS and qSOFA. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:33.

Crouser ED, et al. Monocyte distribution width: a novel indicator of sepsis-2 and sepsis-3 in high-risk emergency department patients. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(8):1018–25.

Lin HA, et al. Clinical impact of monocyte distribution width and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for distinguishing COVID-19 and influenza from other upper respiratory tract infections: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241262.

Martinez FO, et al. Monocyte activation in systemic Covid-19 infection: assay and rationale. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102964.

Polilli E, et al. Comparison of monocyte distribution width (MDW) and procalcitonin for early recognition of sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1):e0227300.

Huang G, Kovalic AJ, Graber CJ. Prognostic value of leukocytosis and lymphopenia for coronavirus disease severity. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8):1839–41.

Yamada T, et al. Value of leukocytosis and elevated C-reactive protein in predicting severe coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;509:235–43.

Sayad B, et al. Leukocytosis and alteration of hemoglobin level in patients with severe COVID-19: association of leukocytosis with mortality. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3(4):e194–e194.

Fathi N, Rezaei N. Lymphopenia in COVID-19: therapeutic opportunities. Cell Biol Int. 2020;44(9):1792–7.

Yan S, Wu G. Is lymphopenia different between SARS and COVID-19 patients? FASEB J. 2021;35(2):e21245.

Biamonte F, et al. Combined lymphocyte/monocyte count, D-dimer and iron status predict COVID-19 course and outcome in a long-term care facility. J Transl Med. 2021;19(1):79.

Harris CK, et al. Bone marrow and peripheral blood findings in patients infected by SARS-CoV-2. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcp/aqaa274.

Huang Y, Zhang Y, Ma L. Meta-analysis of laboratory results in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(5):449–449.

Shi L, et al. Is neutrophilia associated with mortality in COVID-19 patients? A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020;42(6):e244–7.

Henry B, et al. Lymphopenia and neutrophilia at admission predicts severity and mortality in patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(3):e2020008.

Meidaninikjeh S, et al. Monocytes and macrophages in COVID-19: friends and foes. Life Sci. 2021;269:119010.

Pence BD. Atypical monocytes in COVID-19: lighting the fire of cytokine storm? J Leukoc Biol. 2021;109(1):7–8.

Matic S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection induces mixed M1/M2 phenotype in circulating monocytes and alterations in both dendritic cell and monocyte subsets. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(12):e0241097.

Karimi Shahri M, Niazkar HR, Rad F. COVID-19 and hematology findings based on the current evidences: a puzzle with many missing pieces. Int J Lab Hematol. 2021;43(2):160–8.

Singh A, et al. Morphology of COVID-19—affected cells in peripheral blood film. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(5):e236117.

da Silva Gomes Dias S, et al. Lipid droplets fuel SARS-CoV-2 replication and production of inflammatory mediators. bioRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.22.262733.

Chen W, et al. Plasma CRP level is positively associated with the severity of COVID-19. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):18.

Ahnach M, et al. C-reactive protein as an early predictor of COVID-19 severity. J Med Biochem. 2020;39(4):500–7.

Liu SL, et al. Expressions of SAA, CRP, and FERR in different severities of COVID-19. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(21):11386–94.

Cai H, et al. Importance of C-reactive protein in regulating monocyte tissue factor expression in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(7):1224–31.

Osterud B. Tissue factor expression by monocytes: regulation and pathophysiological roles. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1998;9(Suppl 1):S9-14.

Melnikov I, et al. CRP is transported by monocytes and monocyte-derived exosomes in the blood of patients with coronary artery disease. Biomedicines. 2020;8(10):435.

Larsen JB, Pasalic L, Hvas A-M. Platelets in coronavirus disease 2019. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020;46(7):823–5.

Parra-Izquierdo I, Aslan JE. Perspectives on platelet heterogeneity and host immune response in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020;46(7):826–30.

Han H, Yang L, Liu R, et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2020-01884.

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3.

Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(04):844–7.

Hachim MY, et al. D-dimer, troponin, and urea level at presentation with COVID-19 can predict ICU admission: a single centered study. Front Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.585003.

Acknowledgements

The Authors wish to thank all members of the DHA unified electronic system Salama for helping in data collection from the electronic patient medical record.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LA assisted with study design and interpretation of the data, had full access to the study data, assumes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the analysis, and drafted the manuscript. SA assisted with interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. MH conducted the statistical analyses, assisted with the data interpretation and edited the initial draft of the manuscript. NA & FA assisted with data collection & management and contributed to the final editing of the manuscript. RS & AH final editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee (DSREC) of the Dubai Health Authority (DHA) reviewed and approved the present study (DSREC-06/2020-55). Further clarification can be obtained from the DSREC at DSREC@dha.gov.ae. This study was initiated in the DHA all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki). No patients were enrolled for this study hence informed consent was waived off by the Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee (DSREC). No questionnaire or survey was separately created or designed for this study. This was indicated in the IRB application that was submitted to DHA-DSREC which approved the waiver.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

WHO/International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium case record form for severe acute respiratory infections, which is used to develop data collection form for the current study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsuwaidi, L., Al Heialy, S., Shaikh, N. et al. Monocyte distribution width as a novel sepsis indicator in COVID-19 patients. BMC Infect Dis 22, 27 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-07016-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-07016-4