Abstract

Aim

This study has conducted a comparative analysis of common carbapenemases harboring, the expression of resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family efflux pumps, and biofilm formation potential associated with carbapenem resistance among Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) strains with different carbapenem susceptibility. Methods: A total of 90 isolates of A. baumannii from two tertiary hospitals of China were identified and grouped as carbapenem susceptible A. baumannii (CSAB) strains and carbapenem non-susceptible A. baumannii (CnSAB) strains based on the susceptibility to imipenem. Harboring of carbapenemase genes, relative expression of RND family efflux pumps and biofilm formation potential were compared between the two groups. Result: Among these strains, 12 (13.3 %) strains were divided into the CSAB group, and 78 (86.7 %) strains into the CnSAB group. Compared with CSAB strains, CnSAB strains increased distribution of blaOXA−23 (p < 0.001) and ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like (p = 0.034) carbapenemase genes, and a 6.1-fold relative expression of adeB (p = 0.002), while CSAB strains led to biofilm formation by 1.3-fold than CnSAB strains (p = 0.021).

Conclusions

Clinically, harboring more blaOXA−23−like and ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like complex genes and overproduction of adeABC are relevant with carbapenem resistance, while carbapenem susceptible strains might survive the stress of antibiotic through their ability of higher biofilm formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is emerging as an opportunistic nosocomial pathogen and clinically causes serious infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia, urinary tract infection, surgical wound infection, pyemia, meningitis, and peritonitis [1,2,3,4]. A. baumannii has become a clinically successful pathogen owing to its strong tolerance to an adverse environment, complex drug resistance mechanism and plastic genome. This pathogen has caused serious public health problems globally in recent 20 years [5].

Carbapenems, including imipenem, meropenem and doripenem, are important antibiotics in treating A. baumannii infections [6, 7]. According to the results of the antimicrobial sensitive test (AST), clinical isolates of A. baumannii can be divided into carbapenem non-susceptible A. baumannii (CnSAB) and carbapenem susceptible A. baumannii (CSAB). Even following the guidance of AST strictly, the actual treatment effects of A. baumannii are often not so ideal, both for CnSAB and CSAB. Different strains seem to live in different ways. Carrying carbapenemases, overproduction of efflux pumps, low-expression of outer membrane proteins, and biofilm formation may be related to the survival of A. baumannii in the presence of antibiotics. A comparative understanding of CSAB and CnSAB pathogen characteristics is critical for adopting appropriate strategies to control their infection. To the best of our knowledge, most studies focused on the resistance mechanisms, and only a few investigations have attempted comparing CnSAB and CSAB, especially after modifying the clinical breakpoints for imipenem in 2021 (CLSI 2021, 31st Edition; Document M100). In this context, this study aims to investigate the different characterization in carbapenemases harboring, efflux pumps expression level and biofilm formation capability of CnSAB and CSAB strains of A. baumannii.

Methods

Collection and identification of strains

A total of 115 non-repetitive strains of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus - Acinetobacter baumannii complex were collected from two hospitals from July 2018 to December 2019. 90 of these strains were further identified as A. baumannii using rpoB gene sequence analysis with a previously described method [8, 9], and the primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Among them, 48 strains were from the First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University in South China, and 42 strains were from Wuhan No.1 Hospital in Central China. Specimen sources of these isolates included sputum, blood, nasal secretion, alveolar lavage fluid, urine, etc. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University (approval ID 20200511007). The data related to this study were received from the hospital’s information system, and the patient’s informed consent was exempted. Overall, the outcome of this study is expected to benefit patients with the infection of A. baumannii for better therapy.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test (AST)

AST of the above strains was determined by an automated broth microdilution method (Gram-negative susceptibility cards) through the VITEK 2 system (Biomerieux, France) according to the manufacture’s instruction, and susceptibility interpretation was based on the clinical breakpoints from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI 2021, 31st Edition; Document M100). Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27,853 strains were used as the control. According to the CLSI clinical breakpoint to imipenem, these strains were divided into two groups: carbapenem susceptible A. baumannii (CSAB) and carbapenem non-susceptible A. baumannii (CnSAB). In CSAB, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for imipenem was ≤ 2 µg/ml; and in CnSAB, MIC was ≥ 4 mg/L (intermediate: 4 mg/L; resistant: ≥8 mg/L).

Detection of carbapenemases

Based on the already established polymerase chain reaction (PCR) conditions [10], all these 90 strains were subjected to the detection of carbapenemase genes, including blaSIM (Seoul imipenemase), blaVIM (Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamases), blaIMP (imipenemase), blaNDM−1 (New-Delhi metallo-β-lactamase), blaOXA−51−like, blaOXA−23−like, blaOXA−24/40−like and blaOXA−58−like [11, 12]. The detection of ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like was performed using the method of Jane Turton et al [13]. All PCR primers targeting resistance genes and mobile elements used in this study are shown in Table 1.

Relative expression of RND family efflux pumps

The relative gene expressions of adeB, adeJ and adeG were used to evaluate the relative expressions of adeABC, adeFGH and adeIJK efflux pumps, respectively. The preparation methods of RNA templates and quantitative real-time PCR assays were performed based on the earlier reported conditions [10]. The 16 S rRNA gene as control and A. baumannii ATCC 17,978 as a reference strain were used to measure the relative expression levels. All the reactions were carried out in triplicate.

Detection of biofilm production capacity

The biofilm formation assay was performed according to the previous method [14]. A. baumannii strains were cultured overnight and diluted to a density of 0.5 on the McFarland scale. 100 µl of the diluted culture was introduced into the wells of 96-well plate and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C without shaking. All wells were washed three times, and the planktonic bacteria were removed. 125 µl (0.1 %) crystal violet solution was then added into each well and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. The wells were then washed and dried at room temperature. Each well was then added 200 µl of 95 % ethanol and incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. The obtained ethanol-crystal violet solution in each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate to determine the optical density (OD) at 550 nm.

Statistical analysis

Data entry and analysis were performed with Stata/SE 15.1 for windows version 16.0 (Stata Corp LLC, Texas, USA). Categorical variables were described as frequency numbers (percentages). The distribution of sources of samples, age and gender, were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test. Harboring of resistance genes, relative expression of efflux pumps, and biofilm formation between the CSAB and CnSAB groups were compared using the Fisher-Exact or independent t-test. The association of relative expression of RND family efflux pumps and biofilm formation were analyzed using multivariate regression. All tests were two-tailed, and a p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristic of strains

The clinical characteristics of the 90 isolates of A. baumannii are listed in Table 2. In this study, the patients who suffered from the infection of A. baumannii consisted of 72 (80.0 %) males and 18 (20.0 %) females. Among them, 52 (57.8 %) were over 60 years old (including 60), and 38 (42.2 %) were less than 60 years old. Respiratory tract specimens were the most frequent source. These respiratory tract specimens included sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and nasal secretion, and their respective proportions were 71.1 %, 8.9 and 5.6 %, respectively. Five of these strains were isolated from a blood specimen.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

Based on the susceptibility to imipenem, strains were divided into CnSAB and CSAB. Of the 90 strains, 13.3 % (12/90) were carbapenem susceptible (CSAB), and the rest (86.7 %, 78/90) were classified as CnSAB.

Distribution of carbapenemases

As shown in Table 3, no blaSIM, blaVIM and blaIMP genes were detected in these 90 isolates. An intrinsic carbapenemase gene to A. baumannii species, blaOXA−51−like was present in all the 90 (100 %) isolates. The blaOXA−23−like, blaOXA−24/40−like and blaOXA−58−like were present in 83.3 % (75/90), 1.1 % (1/90), and 2.2 % (2/90) isolates, respectively. The blaOXA−23−like was detected positive in 33.3 % (4/12) of the CSAB group and 91.0 % (71/78) of CnSAB, respectively. Compared with CSAB strains, CnSAB showed a statistically significant increasing distribution of blaOXA−23−like (p < 0.001). For another carbapenemase gene, ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like was detected in 28.2 % (22/78) in CnSAB group (p = 0.034). The blaOXA−24/40−like and blaOXA−58−like genes were noted in 1 and 2 strains, respectively. blaNDM−1 gene was detected in 6.4 % (5/78) of CnSAB strains.

Relative expression of RND family pumps

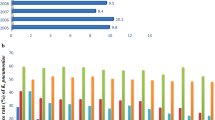

The relative expression of three RND family efflux pumps genes was measured using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (Fig. 1). Compared with CSAB, the relative expressions of adeB, adeJ, and adeG genes in CnSAB were increased by 6.1, 0.9, and 0.9 times, respectively. The relative expression of adeB was significantly increased (p = 0.003), but the relative expressions of adeG (p = 0.709) and adeJ (p = 0.340) were not significantly increased.

Relative expressions of adeB, adeJ and adeG in CSAB and CnSAB strains. The RND family efflux pump expression was determined by the quantitative real-time PCR, and Acinetobacter baumannii strain ATCC 17,978 was taken as a reference. All reactions were carried out in triplicate. The black dot indicates carbapenem susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii (CSAB) strains; the Black square denotes carbapenem non-susceptible Acinetobacter baumannii (CnSAB) strains. S, significant; NS, not significant

Biofilm forming capacity

The biofilm-forming potential of strains was measured through violet crystalline dying. As shown in Fig. 2, CSAB strains produced biofilm with an OD of 0.29 ± 0.04, while CnSAB strains produced biofilm with an OD of 0.23 ± 0.02. the biofilm produced by CSAB strains was 1.3 times higher than that of CnSAB. There was significant difference in biofilm forming capacity between the two groups (p = 0.021).

Biofilm formation capacity of CSAB and CnSAB strains. A The biofilm of A. baumannii by violet crystalline dying (under oil lens, 1000x). B Comparison of biofilm production between carbapenem susceptible (CSAB) and carbapenem non-susceptible (CnSAB) groups of A. baumannii. S, significant; NS, not significant

Association between the relative expression of RND family efflux pumps and biofilm formation

The regression analysis results of the correlation between the relative expression of RND family efflux pumps and biofilm formation are shown in Table 4. The relative expressions of three proteins, adeB, adeG, adeJ, demonstrate no significant association with biofilm formation capacity (p = 0.128, 0.218, and 0.601, respectively).

Discussion

A. baumannii is an important pathogen of nosocomial infections. This decade witnessed a series of clinical infections events and led to high clinical mortality [15,16,17,18,19]. Outstanding drug resistance and tolerance to the harsh environment make A. baumannii to be a successful clinical pathogen [1, 20]. Earlier studies have observed that powerful resistance was associated with hydrolyzing enzymes, efflux pumps, biofilm and outer membrane in A. baumannii [11, 21, 22]. This study was designed to compare the characterization of carbapenemases harboring, efflux pumps relative expression and biofilm formation capability in the A. baumannii strains with different carbapenem susceptibility. For this, 90 isolates of A. baumannii obtained from two hospitals were identified and were divided into CSAB and CnSAB groups based on their imipenem susceptibility. The obtained results indicate that CnSAB strains increased distribution of blaOXA−23 (P < 0.001) and ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like (p = 0.034) carbapenemase genes, and a 6.1-fold relative expression of adeB (p = 0.002) was noted compared with CSAB strains, while the biofilm produced by CSAB strains was 1.3 times higher than that of CnSAB, (p = 0.021).

Production of multiple carbapenemases is effective for carbapenem resistance. The most important carbapenemases in A. baumannii include class B metallo-β -lactamases (MBLs) and class D oxacillinases (OXAs). OXAs include blaOXA−51−like, blaOXA−23−like, blaOXA−24/40−like and blaOXA−58−like, and MBLs include blaSIM (Seoul imipenemase), blaVIM (Verona integron-encoded metallo-beta-lactamases), blaIMP (imipenemase), blaNDM-1 (New-Delhimetallo-β-lactamase) [23] [24] [25].

Whereas the composition of different carbapenemases was different in different regions, the most common mechanism for carbapenem resistance was harboring blaOXA−23 in A. baumannii. Janak Koirala et al. reported blaOXA−23−like (52 %) and blaOXA−24/40−like (28 %) were the most common genes in CnSAB in central Illinois, the United States. [26]Sunil Kumar et al. found a high prevalence of blaOXA−23−like (97.7 %) among the carbapenem-resistant strains followed by blaNDM−1 (29.1 %) and blaOXA58−like (3.5 %) in India [27]. Udomluk Leungtongkam found a pattern of blaOXA−23 (82.6 %), blaNDM−1 (9.1 %), blaOXA−24/40−like (0.3 %), and blaOXA−58−like (6.5 %) in 339 A. baumannii in Thailand [24]. In the current study, a pattern of blaOXA−23−like (83.3 %), ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like (24.4 %), blaNDM−1 (5.6 %), blaOXA−24/40−like (1.1 %), and blaOXA−58−like (2.2 %) was detected in CnSAB. CnSAB strains showed a statistically significant increase of harboring of blaOXA−23 (p < 0.001) compared with CSAB strains.

Another interesting finding was that harboring the ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like gene might be another important factor in carbapenem resistance. The chromosome encoded blaOXA−51−like gene is intrinsic, but the solitary OXA-51 enzyme only showed a weak hydrolyzing activity to carbapenems. While with an additional genetic element ISAba1 upstream insertion, the ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like complex may result in OXA-51 overproduction which confers resistance to carbapenem. In this study, a significant difference in the carrying of ISAba1/blaOXA−51−like between CnSAB and CSAB strains (p = 0.034) was observed. In this study, four isolates harboring blaOXA−23−like were found susceptible to carbapenem. This may be due to some mutations in blaOXA−23−like gene or decrease of expression of this gene. Based on this, a further quantitative detection for blaOXA−23−like expression is necessary to evaluate the actual contribution to carbapenem resistance in further research.

Besides carbapenemase, overproduction of efflux pumps could be another important factor contributing to drug resistance. Efflux pumps can extrude a variety of antimicrobial agents and reduce the accumulation of antibiotics in bacteria. According to the reports in this decade, five super families of efflux pumps have been found in A. baumannii: the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters family, the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family, the major facilitator super (MFS) family, and the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family [10, 28,29,30,31]. The three RND efflux family members, adeABC, adeFGH and adeIJK, are the most important pumps for carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii. The relative expressions of adeB, adeJ and adeG were commonly used to evaluate the relative expression of adeABC, adeFGH, and adeIJK efflux pumps, respectively. Also, by comparing with CSAB strains, the relative expression of adeB, adeJ, and adeG genes in CnSAB strains increased by 6.1-fold (p = 0.003), 0.9-fold (p = 0.709), and 0.9-fold (p = 0.340), respectively. These results agree with Yili Chen’s findings, where they found a significantly increased expression of adeB from carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii strains compared with susceptible strains [32]. This indicates the overproduction of adeABC efflux pump might be another potential cause for carbapenem resistance. In this study, only RND family pumps were discussed, but the contribution of other efflux family pumps needs to be examined further.

Biofilm formation of A. baumannii often leads to relapse of chronic infection and disease delay. The relationship between biofilm formation potential and resistance of carbapenems is controversial. Using confocal laser scanning microscopy, Dahdouh et al. found that carbapenem resistant strains could produce more biofilm than susceptible strains [33]. In comparison, Perez et al. reported an inverse relationship between the biofilm formation ability and carbapenem resistance level. They observed meropenem susceptible isolates produced more biofilm than the resistant ones in nosocomial A. baumannii strains [34]. This study noticed that the biofilm produced by CSAB strains was 1.3 times higher than that of CnSAB, and the difference is significant (p = 0.021). It was indicated that the carbapenem susceptible strains might take advantage of the biofilm formation to survive the pressure of antimicrobials. This explains why the clinical therapy for A. baumannii sensitive strains is often not so ideal, even following the guide of AST strictly in vitro.

The relative expression of RND efflux pumps influencing biofilm formation is controversial. Yoon et al. reported that mutants with up-regulation expression of the AdeABC, AdeFGH and AdeIJK efflux pumps reduced biofilm formation compared with wild strains. In contrast, He et al. reported that overexpression of the AdeFGH efflux pump is beneficial for biofilm formation in A. baumannii. In this study, a regression analysis was attempted. No relationship between the relative expressions of adeB, adeG, and adeJ, as well as biofilm formation capacity in these 90 isolates, was found out.

Besides the above observations, this study has several limitations. Firstly, the sample size was relatively small, and the source of the strains was only from two hospitals. Secondly, this study only discussed the relationship of overproduction of three members of the RND family, but other efflux pump families and outer membrane proteins were not involved. Thus, the experimental data analysis might be influenced by these limitations. Thirdly, different resistance mechanisms may have synergistic or antagonistic effects, and the interactions between those resistance mechanisms have not been considered in this study.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Antunes LCS, Visca P, Towner KJ. Acinetobacter baumannii: Evolution of a global pathogen. Pathog Dis. 2014;71:292–301.

Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: Emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538–82.

Holmes CL, Anderson MT, Mobley HLT, Bachman MA. Pathogenesis of gram-negative bacteremia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021;34:1.

Lima WG, Silva Alves GC, Sanches C, Antunes Fernandes SO, de Paiva MC. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in patients with burn injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Burns. 2019;45:1495–508.

Ayobami O, Willrich N, Harder T, Okeke IN, Eckmanns T, Markwart R. The incidence and prevalence of hospital-acquired (carbapenem-resistant) Acinetobacter baumannii in Europe, Eastern Mediterranean and Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Microb Infect. 2019;8:1747–59.

Durante-Mangoni E, Zarrilli R. Global spread of drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: molecular epidemiology and management of antimicrobial resistance. Fut Microbiol. 2011;6:407–22.

Doi Y. Treatment options for carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(Suppl 7):S565–75.

Gundi VAKB, Dijkshoorn L, Burignat S, Raoult D, La Scola B. Validation of partial rpoB gene sequence analysis for the identification of clinically important and emerging Acinetobacter species. Microbiology. 2009;155:2333–41.

La Scola B, Gundi VAKB, Khamis A, Raoult D. Sequencing of the rpoB gene and flanking spacers for molecular identification of Acinetobacter species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:827–32.

Zhang Y, Li Z, He X, Ding F, Wu W, Luo Y, et al. Overproduction of efflux pumps caused reduced susceptibility to carbapenem under consecutive imipenem-selected stress in Acinetobacter baumannii. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:457–67.

El-Shazly S, Dashti A, Vali L, Bolaris M, Ibrahim AS. Molecular epidemiology and characterization of multiple drug-resistant (MDR) clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;41:42–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2015.10.016.

Yang YS, Chen HY, Hsu WJ, Chou YC, Perng CL, Shang HS, et al. Overexpression of AdeABC efflux pump associated with tigecycline resistance in clinical Acinetobacter nosocomialis isolates. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;25:512.e1-512.e6.

Turton JF, Ward ME, Woodford N, Kaufmann ME, Pike R, Livermore DM, et al. The role of ISAba1 in expression of OXA carbapenemase genes in Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;258:72–7.

Krzyściak P, Chmielarczyk A, Pobiega M, Romaniszyn D, Wójkowska-Mach J. Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from hospital-acquired infection: biofilm production and drug susceptibility. APMIS. 2017;125:1017–26.

Schooley RT, Biswas B, Gill JJ, Hernandez-Morales A, Lancaster J, Lessor L, et al. Development and use of personalized bacteriophage-based therapeutic cocktails to treat a patient with a disseminated resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:1.

Xiao J, Zhang C, Ye S. Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis in children: a case series and literature review. Infection. 2019;47:643–9.

Yamasmith E, Chongtrakool P, Chayakulkeeree M. Isolated pulmonary fusariosis caused by Neocosmospora pseudensiformis in a liver transplant recipient: A case report and review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2020;22:e13344.

Aykota MR, Sari T, Yilmaz S. Successful treatment of extreme drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infection following a liver transplant. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14:408–10.

Xu A, Zhu H, Gao B, Weng H, Ding Z, Li M, et al. Diagnosis of severe community-acquired pneumonia caused by Acinetobacter baumannii through next-generation sequencing: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:45.

Dijkshoorn L, Nemec A, Seifert H. An increasing threat in hospitals: multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:939–51.

Jia W, Li C, Zhang H, Li G, Liu X, Wei J. Prevalence of genes of OXA-23 carbapenemase and AdeABC efflux pump associated with multidrug resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in the ICU of a comprehensive hospital of Northwestern China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:10079–92.

Sun H, Xiao G, Zhang J, Pan Z, Chen Y, Xiong F. Rapid simultaneous detection of blaoxa-23, Ade-B, int-1, and ISCR-1 in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii using single-tube multiplex PCR and high resolution melting assay. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:1573–81.

Karampatakis T, Tsergouli K, Politi L, Diamantopoulou G, Iosifidis E, Antachopoulos C, et al. Polyclonal predominance of concurrently producing OXA-23 and OXA-58 carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains in a pediatric intensive care unit. Mol Biol Rep. 2019;46:3497–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-019-04744-4.

Leungtongkam U, Thummeepak R, Wongprachan S, Thongsuk P, Kitti T, Ketwong K, et al. Dissemination of blaOXA-23, blaOXA-24, blaOXA-58, and blaNDM-1 Genes of Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from Four Tertiary Hospitals in Thailand. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24:55–62.

Hou C, Yang F. Drug-resistant gene of blaOXA-23, blaOXA-24, blaOXA-51 and blaOXA-58 in Acinetobacter baumannii. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:13859–63.

Koirala J, Tyagi I, Guntupalli L, Koirala S, Chapagain U, Quarshie C, et al. OXA-23 and OXA-40 producing carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Central Illinois. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;97: 114999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2020.114999.

Kumar S, Patil PP, Singhal L, Ray P, Patil PB, Gautam V. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates reveals the emergence of blaOXA-23 and blaNDM-1 encoding international clones in India. Infect Genet Evol. 2019;75:103986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2019.103986.

Fernández L, Hancock REW. Adaptive and mutational resistance: role of porins and efflux pumps in drug resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:661–81.

Adabi M, Talebi-Taher M, Arbabi L, Afshar M, Fathizadeh S, Minaeian S, et al. Spread of efflux pump overexpressing-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance and multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by using an efflux pump inhibitor. Infect Chemother. 2015;47:98–104.

Hou PF, Chen XY, Yan GF, Wang YP, Ying CM. Study of the correlation of imipenem resistance with efflux pumps AdeABC, AdeIJK, AdeDE and AbeM in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Chemotherapy. 2012;58:152–8.

Yoon EJ, Courvalin P, Grillot-Courvalin C. RND-type efflux pumps in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii: Major role for AdeABC overexpression and aders mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:2989–95.

Chen Y, Ai L, Guo P, Huang H, Wu Z, Liang X, et al. Molecular characterization of multidrug resistant strains of Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from pediatric intensive care unit in a Chinese tertiary hospital 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1108 Medical Microbiology. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:1–7.

Dahdouh E, Orgaz B, Gómez-Gil R, Mingorance J, Daoud Z, Suarez M, et al. Patterns of biofilm structure and formation kinetics among Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates with different antibiotic resistance profiles. Med Chem Comm. 2016;7:1.

Perez LRR. Acinetobacter baumannii displays inverse relationship between meropenem resistance and biofilm production. J Chemother. 2015;27:13–6.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the engineers of the medical information system. The authors would like to express their gratitude to EditSprings (https://www.editsprings.com/) for the expert linguistic services provided.

Funding

This project was financially supported by the Grant from Basic research project of Shenzhen Science and technology innovation Commission (No. JCYJ20190806164011195).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG, YZ and BF conceived and designed the experiment, YZ, BF, ZT, YL, YN and YW performed the experiment, YZ, BF and YL analyzed the data, YZ, FD, and BF participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (Approval ID: 20200511007).

Consent for publication

Not applicable since there are no details on individuals reported within the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Fan, B., Luo, Y. et al. Comparative analysis of carbapenemases, RND family efflux pumps and biofilm formation potential among Acinetobacter baumannii strains with different carbapenem susceptibility. BMC Infect Dis 21, 841 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06529-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06529-2