Abstract

Background

The role of non-group A streptococci and Fusobacterium necrophorum in pharyngotonsillitis has been disputed and few prospective studies have evaluated the effect of antibiotic treatment. This study uses registry data to investigate the relation between antibiotic prescription for pharyngotonsillitis in primary healthcare and return visits for pharyngotonsillitis, complications, and tonsillectomy.

Methods

Retrospective data were extracted from the regional electronic medical record system in Kronoberg County, Sweden, for all patients diagnosed with pharyngotonsillitis between 2012 and 2016. From these data, two cohorts were formed: one based on rapid antigen detection tests (RADT) for group A streptococci (GAS) and one based on routine throat cultures for β-haemolytic streptococci and F. necrophorum. The 90 days following the inclusion visit were assessed for new visits for pharyngotonsillitis, complications, and tonsillectomy, and related to bacterial aetiology and antibiotic prescriptions given at inclusion.

Results

In the RADT cohort (n = 13,781), antibiotic prescription for patients with a positive RADT for GAS was associated with fewer return visits for pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days compared with no prescription (8.7% vs. 12%; p = 0.02), but not with the complication rate within 30 days (1.5% vs. 1.8%; p = 0.7) or with the tonsillectomy rate within 90 days (0.27% vs. 0.26%; p = 1). In contrast, antibiotic prescription for patients with a negative RADT was associated with more return visits for pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days (9.7% vs. 7.0%; p = 0.01). In the culture cohort (n = 1 370), antibiotic prescription for patients with Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp. equisimilis was associated with fewer return visits for pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days compared with no prescription (15% vs. 29%; p = 0.03).

Conclusions

Antibiotic prescription was associated with fewer return visits for pharyngotonsillitis in patients with a positive RADT for GAS but with more return visits in patients with a negative RADT for GAS. There were no differences in purulent complications related to antibiotic prescription.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infectious pharyngotonsillitis can be caused by a wide array of viruses and bacteria, of which Streptococcus pyogenes (group A streptococci, GAS) is the most important pathogen and the only one that warrants antibiotic treatment according to most guidelines [1,2,3,4]. The indication of antibiotic therapy, however, is confined to reducing symptoms as non-purulent complications of GAS such as rheumatic fever and glomerulonephritis are rare in high-income countries [3] and purulent complications such as peritonsillitis, sinusitis, and media otitis occur in less than 1% of patients [5].

The Sore Throat Guideline Group within the European Society for Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases advocates using the Centor scoring system (one point each for fever, cervical lymphadenitis, tonsillar coating, and absence of cough) [6] to select patients with a higher likelihood of GAS infection (i.e., 3–4 criteria) and considering using a Rapid Antigen Detection Test (RADT) for these patients [3]. Throat cultures are not necessary for routine diagnosis of GAS nor after a negative RADT [3]. Penicillin V, twice or three times daily for 10 days, is the recommended treatment of GAS [3], but should be avoided in patients with Centor score 0–2 as these patients do not seem to benefit from antibiotics [3]. The Swedish Medical Products Agency has adopted this guideline for the most part but stresses that an RADT should only be performed in patients with Centor scores 3–4 as these are the patients who could benefit from antibiotic treatment [1].

In addition to GAS, Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis (SDSE), formerly described as large colony group C or G streptococci in the Lancefield classification system [7], has been detected in 9 to 15% of young adults with pharyngotonsillitis [8,9,10], and the anaerobe Fusobacterium necrophorum has been detected in 18–19% of patients with pharyngotonsillitis in primary healthcare (PHC) [11, 12]. Both bacteria, however, are also recovered from healthy controls, and their roles as pathogens in pharyngotonsillitis are still disputed [10,11,12,13,14]. F. necrophorum, the main pathogen causing the severe but unusual Lemierre’s syndrome [15], has been associated with peritonsillar abscesses [16] and several case reports have described complications following pharyngotonsillitis associated with group C and group G streptococci [3]. Most cases of peritonsillitis, however, are not preceded by a recorded pharyngotonsillitis [17] and few prospective studies have approximated the incidence of complications after an episode of pharyngotonsillitis. Furthermore, no randomised controlled study has shown that antibiotic treatment of pharyngotonsillitis caused by SDSE or F. necrophorum lowers the complication rate [10, 12].

This study uses registry data to prospectively follow patients with a PHC-recorded pharyngotonsillitis for 90 days and to quantify the incidence of new visits for pharyngotonsillitis, complications, and tonsillectomy in relation to initial aetiology and antibiotic prescription.

Methods

Study population and setting

This study was conducted in Kronoberg County in southern Sweden. The Swedish healthcare system is mainly tax-funded and is equally accessible to all inhabitants, with the services decentralised to 21 regional councils. PHC is provided by approximately 1 200 PHC centres (PHCC) dispersed throughout the country. People are encouraged to contact their PHCC before seeking emergency care at hospitals. Therefore, sore throat and other respiratory infections are usually managed by the PHCC.

During the study period (2012–16), the median population in Kronoberg County was 189 292, about 2% of the Swedish population. This population was served by two hospitals and 34 PHCCs, 31 of which participated in the study. The PHCCs were generally open between 08:00 and 17:00, and two out-of-hours centres also served patients between 17:00 and 21:00. In most cases, patients were first assessed over the telephone by a triage nurse, who decided if a physician’s visit was necessary. All visits with a physician required that the physician register a diagnosis code according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) or its modified Swedish PHC edition (KSH97-P) [18].

This paper is reported following the STROBE statement [19] and the RECORD statement [20].

Data extraction

Retrospective data for the years 2012–16 were extracted from the regional electronic medical record (EMR) system (Cambio Cosmic, Cambio Healthcare Systems, Linköping, Sweden) and the laboratory information system (ADBAKT, Autonik, Nyköping, Sweden). The data extraction was performed in four steps.

In the first step, all patients were identified who received a diagnosis code for pharyngotonsillitis (J02 or J03) from a PHCC or hospital clinic physician during the study period (Step 1, Fig. 2). Data regarding age, sex, RADTs, throat cultures, and antibiotic prescriptions from PHCCs and hospital clinics were then extracted and linked using the Swedish personal identification number and visit date. As the indication for antibiotic treatment could not be extracted from the EMR system, the following antibiotics relevant for treating pharyngotonsillitis in accordance with Swedish guidelines [1] were identified: phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin V), cefadroxil, and clindamycin. In addition, amoxicillin, erythromycin, and azithromycin were included as they are approved by the Swedish Medical Products Agency for treating pharyngotonsillitis. However, data were unavailable that would confirm whether patients collected their medication at a pharmacy or complied with prescribed treatment regime.

In the second step, patients who had at least one eligible visit to a PHCC with aetiological testing (see below) were selected (Step 2, Fig. 2). Five exclusion criteria for a visit were used: (1) visit date during the first 30 days of the study period; (2) a diagnosed pharyngotonsillitis or complication (defined as peritonsillitis, media otitis, sinusitis, lymphadenitis or sepsis, see Additional file 1: Table S1) the previous 30 days; (3) antibiotic prescription (as defined above) the previous 30 days; (4) a complication diagnosed on the same day as the visit; and (5) prescription of an antibiotic not indicated for a sore throat (Fig. 2). Aetiological testing was defined as an RADT for GAS performed on the same date as the visit or a throat culture performed within seven days. RADTs performed on the first day and cultures performed within a week were included because this routine mirrors clinical practice. Early descriptive analysis also revealed that most cultures were performed on the same day as the index visit, and an absolute majority within 7 days.

In the third step, a cohort (cohort 1) was formed with all patients from step 2 where an RADT had been performed (Step 3, Fig. 2). The first eligible visit for each patient was denoted as the index visit.

In the fourth step, using the same patients as in step 2, a new, explanatory cohort was created (cohort 2), with all patients who had been cultured (step 4, Fig. 2). As before, the first eligible visit with a culture was denoted as the index visit. As most patients had an RADT performed before they were cultured, many patients in cohort 2 were also in cohort 1, with common index visit dates.

In both cohorts, patients were grouped by antibiotic prescription on the day of their index visit, as early descriptive analysis revealed that most patients with a prescription were prescribed antibiotics during their index visit, whereas subsequent prescriptions were often made during a new visit, which we wanted to count as an outcome.

Although the main criteria for inclusion in this study was a visit to a PHCC, the outcomes were defined as a visit to either a PHCC or a hospital clinic (Fig. 1). This was especially important for tonsillectomy, as it is never coded for in PHC, as well as for peritonsillitis, as these patients sometimes visit an emergency department at a hospital without first visiting a PHCC. If a patient had separate index visit dates for the two cohorts, the exclusion criteria made sure that no index visit would be registered as an outcome in the other cohort.

Observation time for patients with pharyngotonsillitis. In cohort 1 the index visit was defined as the first visit with a rapid antigen detection test (RADT) for group A streptococci (GAS) performed on the same day. In cohort 2, the index visit was defined as the first visit where a throat culture was performed within seven days. For a visit to be eligible there should neither be a visit for pharyngotonsillitis or a complication nor an antibiotic prescription during the last 30 days. In the follow-up, each patient was assessed for new visits for pharyngotonsillitis, a complication, and tonsillectomy up to 90 days from the index visit

Microbiological procedures

The RADT kit for GAS used in Kronoberg County during the study period was QuickVue Dipstick Strep A (Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA), a lateral-flow immunoassay using antibody-labelled particles [21]. The test detects viable and nonviable organisms directly from throat swabs.

Routine throat cultures for the recovery of large colony β-haemolytic streptococci used standard procedures, as previously described [9]. Starting in 2013, the laboratory also offered an extended throat culture that added an anaerobic plate for the recovery of F. necrophorum [9]. In late 2013, with the introduction of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization with time-of-flight mass spectrometer (MALDI-TOF), the reporting of streptococci transitioned from Lancefield classification to species identification. As a result, GAS was reported as S. pyogenes and most group C and G streptococci were reported as SDSE. In this study, group C or G streptococci were reported as SDSE. During the study period, before the transition, group C and G streptococci constituted 40% of all β-haemolytic streptococci in throat cultures; after the transition, the corresponding proportion for SDSE was 42% (data not shown).

Statistical methods

Data were cleaned and analysed using Excel 2019 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and SPSS 25.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables with non-normal distribution or small sample sizes were reported as median (interquartile range, IQR). Categorical data were compared with two-sided Pearson χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test for independent groups, and McNemar test or Cochran’s Q test for dependent groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

* For patients with multiple eligible visits, the first visit was denoted index visit. Due to double aetiological testing or multiple eligible visits, 1 127 patients were included in both cohorts.

Study population

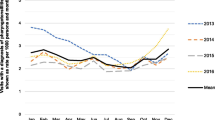

Between 2012 and 2016, 20,858 patients were diagnosed with pharyngotonsillitis during at least one PHCC or hospital clinic visit. Of these, 14,024 had at least one eligible visit to a PHCC with aetiological testing, and from these patients two cohorts were formed (Fig. 2). Most index visits in cohort 1 and 2 took place during office hours (84% and 88%, respectively).

Flow chart of inclusion. All patients diagnosed with pharyngotonsillitis during a primary healthcare centre visit or hospital clinic visit in Kronoberg County during 2012–16 were selected from registry data (Step 1). From the group of patients with at least one eligible visit to a PHCC with aetiological testing (Step 2), two cohorts were created in turns: one based on rapid antigen detection testing (RADT) for group A streptococci (GAS) (Step 3), and one based on throat cultures (Step 4). As both cohorts were created from the same population, a patient could be included in both cohorts

Aetiology

In cohort 1, the RADT was positive for GAS in 9 170 patients (67%). In cohort 2, a regular culture was performed in 745 (54%) patients and an extended culture was performed in 625 (46%) patients. Of the 1 370 cultures registered within seven days of the index visit, 1 128 (82%) were performed on the same day as the index visit (Additional file 1: Table S2). Bacterial growth was found in 231 (31%) of the regular cultures and 234 (37%) of the extended cultures. Overall, GAS was detected in 201 (15%) patients and SDSE in 190 (14%) patients. F. necrophorum was detected in 95 (15%) patients who had extended cultures.

Characteristics in relation to aetiology

GAS was most prevalent in children aged 0–14, with 80% of RADTs positive, whereas SDSE and F. necrophorum were most prevalent in patients aged 15–29. Table 1 lists the background characteristics of the patients in relation to aetiology.

Frequency of outcomes

In the RADT cohort, 8.6% of the patients made a new visit for pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days (median = 12 days, IQR 4–16) and 1.6% made a new visit for a complication within 30 days (median = 12 days, IQR 3–21). Peritonsillitis accounted for 29% of these complications (median = 3 days, IQR 2–14) (Additional file 1: Table S3).

In the culture cohort, 20% of the patients made a new visit for pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days (median = 3 days, IQR 2–6) and 3.8% made a new visit for a complication within 30 days (median = 3 days, IQR 2–5). Peritonsillitis accounted for 78% of these complications (median = 2 days, IQR 2–5). Of the 51 patients with a complication, 61% were cultured on the same day as the complication, 35% were cultured at least one day before the complication, and two were cultured later.

Antibiotics and outcomes

In the RADT cohort, in patients with a positive RADT pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days was less common in those who were prescribed antibiotics (8.7%; 95% CI 8.1–9.3%) than in those who were not prescribed antibiotics (12%; 95% CI 9.2–16%) (Table 2). In contrast, antibiotic prescription for patients with a negative RADT was associated with a higher proportion of pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days (9.7%; 95% CI 8.4–11%) compared to patients with no prescription (7.0%; 95% CI 6.1–8.0%). Antibiotic prescription was not associated with complication rates or tonsillectomy rates regardless of RADT result.

In the culture cohort, antibiotics were prescribed to 717 (52%) patients on the same day as the index visit and to another 159 (12%) patients during the following seven days (Additional file 1: Table S4). Only 106 (7.7%) patients were prescribed an antibiotic before a sample for culture was obtained. In patients with SDSE antibiotic prescription was associated with a lower proportion of pharyngotonsillitis within 30 days compared with no prescription (Table 3). In contrast, in patients with a negative culture antibiotic prescription was associated with a larger proportion of pharyngotonsillitis and peritonsillitis within 30 days, compared with no prescription.

In the RADT cohort, the proportion of peritonsillitis within 30 days differed with antibiotic chosen both in patients with a positive RADT and a negative RADT, with the lowest proportions among patients who were prescribed penicillin V (Table 4). In the culture cohort, antibiotic type was not associated with the outcomes.

Discussion

In this registry-based study of patients diagnosed with pharyngotonsillitis at a visit in primary healthcare, antibiotic prescription was associated with a lower proportion of return visits for pharyngotonsillitis in patients with a positive RADT for GAS but with a higher proportion of return visits in patients with a negative RADT for GAS. Regardless of test result, antibiotic prescription was not associated with a reduced incidence of purulent complications.

Meaning of the study

With RADTs being positive in 67% of tested patients (i.e. 47% of the whole population studied), GAS was the most common aetiology in our material. This proportion is much higher than expected from prevalence studies [3, 9, 22] and probably points to a classification bias, where the choice of diagnosis codes might have been affected by the test result. In throat cultures, all detected bacteria were equally common, but this finding is hard to interpret as the reason for obtaining a sample for culture (e.g. a more severe clinical presentation) is unknown. Moreover, a positive RADT should reduce the diagnostic necessity of a culture, so the true prevalence of GAS could be underestimated. The prevalence (15%) of F. necrophorum in prolonged anaerobic culture suggests that a similar proportion of routine cultures for streptococci might also harbour F. necrophorum. Certainly, the clinical presentation could have led to a selection bias of extended cultures; however, recent meta-analyses have reported a 18–19% prevalence of F. necrophorum in patients with a sore throat diagnosed in PHC [e, 12]. In our study, F. necrophorum and SDSE were most prevalent among patients aged 15–29. This finding is in line with previous studies: a low prevalence of F. necrophorum and SDSE in children and the highest prevalence in adolescents and young adults [8,9,10,11, 23]. Conversely, GAS was most prevalent in children, which probably reflects a large proportion of carriage in this age group [22, 24].

There was an association between antibiotic prescription and fewer return visits for pharyngotonsillitis in patients with a positive RADT, suggesting a protective role for antibiotics. This finding contrasts with previous findings of increased re-attendance in patients prescribed an immediate antibiotic due to changed expectations and behaviour (i.e., “medicalisation”) [25,26,27]. On the other hand, antibiotics were associated with a higher rate of return visits for pharyngotonsillitis in patients with a negative RADT, which may suggest that the treatment was not effective for this group or that there was a medicalising effect.

Although the culture cohort only constituted a small proportion of all patients, there was an association between antibiotic prescription and fewer return visits for pharyngotonsillitis in patients with SDSE, suggesting a protective role of antibiotics in a subset of the patients with a negative RADT. Surprisingly, patients with negative cultures and antibiotic prescription had a higher incidence of all outcomes measured regardless of the antibiotic used for treatment. Our first thought was that most of these patients had initiated antibiotic treatment before being cultured, but this was only the case in 10% of the patients. Other explanations might be medicalisation, ineffective antibiotics, and confounding by indication (i.e., patients with more severe illness are more likely to receive antibiotics) [28].

Antibiotic prescription was not associated with fewer complications in any cohort. However, complications, especially peritonsillitis, are rare outcomes, and since 95% of the patients with a positive RADT were prescribed antibiotics, the comparison group was rather small. The actual numbers did point to a protective role for antibiotics for complications in patients with a positive RADT (Table 2), but there might have been too few cases to detect a significant difference. The small numbers were also evident in the culture cohort as almost none of the comparisons, no matter how large the difference, were statistically significant. The complication rate in this study was similar to a previous registry study in PHC [29] but lower than the average in randomised controlled trials [5]. Previous studies on the protective role of antibiotics are somewhat conflicting, with the limited trial evidence suggesting a lowered relative risk (RR = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.01–0.79, in studies conducted after the 1950s) [5], but large recent observational studies suggest either no protective role [17, 29] or a very small absolute risk reduction with a huge Number needed to treat (NNT) [30, 31].

Most patients who developed peritonsillitis were diagnosed within a few days after inclusion, with a median of three days in the RADT cohort and two days in the culture cohort. In the long-term follow-up, almost no new cases emerged between 30 and 60 days. These findings are consistent with previous reports of a very fast onset of peritonsillitis [17, 29, 32, 33], suggesting that some of the cases of peritonsillitis might already have been imminent or misdiagnosed as pharyngotonsillitis at inclusion.

Most treated patients received penicillin V, but the overall picture was that the antibiotic chosen was unrelated to the outcomes, a finding in line with a previous meta-analysis [34]. The exception was peritonsillitis and tonsillectomy in the RADT cohort, where penicillin V was associated with fewer cases both in patients with a positive RADT and in patients with a negative RADT. In Sweden, patients with recurring pharyngotonsillitis are generally required to have tried three types of antibiotics before being eligible for tonsillectomy; therefore, clindamycin and cefadroxil, which are second-choice antibiotics, might be associated with complications and tonsillectomy more than penicillin V.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

To our knowledge, this is the largest registry-based study investigating pharyngotonsillitis in PHC, with almost complete data on all recorded diagnoses of pharyngotonsillitis, complications and tonsillectomies for five years, from PHC (office hours and out-of-hours) and hospital clinics. In addition, this is the first study to present data on patients who had F. necrophorum detected in routine cultures. Unlike case–control studies and case reports, this study followed a cohort of patients with pharyngotonsillitis prospectively to estimate the incidence of outcomes. As no randomised controlled trial has been sufficiently sized to study the effect of antibiotics on non-group A streptococci and F. necrophorum in patients with pharyngotonsillitis, this study offers valuable observational data.

However, a registry study comes with inherent weaknesses. For example, we did not know the clinical circumstances of the patients (e.g. severity and duration of symptoms, patients’ expectations, and physicians’ intentions with tests and antibiotic prescription), differential diagnostic reasoning, and inter-rater reliability in terms of diagnostic skills and coding. Therefore, all results are based on the factual codes, test results, and prescriptions registered in the EMR system, a circumstance that calls for a cautious interpretation of the results. On the other hand, this study is based on a large quantity of real-life clinical data from PHC, mirroring both the disease panorama and the behaviour of physicians, nurses, and patients rather than on experimental trial data on a small, selected, and closely monitored population.

The definition of pharyngotonsillitis was confined to the applicable codes in ICD-10 (J02.x and J03.x) although we know from clinical experience and previous studies [35] that sore throats are sometimes coded as “upper respiratory infection” or “viral infection”, especially if the patient has compelling viral symptoms. We made this choice because sore throat as a symptom does not lend itself to registry-based studies, and other codes encompass too many conditions to be useful. Narrowing in on ICD codes for pharyngotonsillitis, however, might have selected a population with a higher likelihood to benefit from antibiotics.

Excluding patients with a diagnosed complication on the same day might have underestimated the complication rate of certain bacteria. However, the primary aim was not to establish a link between aetiology and complications but to follow patients with a pharyngotonsillitis in PHC and study the effect of antibiotic prescription on different outcomes. Another study, focusing on complications, especially peritonsillitis, is nonetheless fully possible with this database and already in the planning.

Unanswered questions and future research

To better appreciate the effect of antibiotic treatment on resolution of symptoms, relapses, and complications in patients with non-group A streptococcal bacterial aetiology, a sufficiently sized randomised controlled trial is warranted. As regular penicillin V was found to be non-inferior to clindamycin and cefadroxil in this study, it might then be an interesting candidate to investigate further. The prevalence of throat cultures was low in our material, and any subsequent registry study on this topic will need to consider this in sizing calculations.

Conclusions

Antibiotic prescription was associated with a lower proportion of return visits for pharyngotonsillitis in patients with a positive RADT for GAS but with a higher proportion of return visits in patients with a negative RADT. Antibiotic prescription was not associated with a reduced incidence of purulent complications regardless of test result. Routine throat cultures were sparse in our setting (in line with national guidelines) and too few to draw any strong conclusions about the possible divergent outcomes in patients positive for SDSE and/or F. necrophorum.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

01 November 2021

In the online version of this article, the funding note should be update. The article has been updated.

Abbreviations

- GAS:

-

Group A streptococci

- EMR:

-

Electronic medical record

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- PHC:

-

Primary healthcare

- PHCC:

-

Primary healthcare centres

- RADT:

-

Rapid antigen detection test

- SDSE:

-

Streptococcus dysgalactiae Subspecies equisimilis

References

Läkemedelsverket [Swedish Medical Products Agency]. Handläggning av faryngotonsillit i öppenvård – ny rekommendation [Management of pharyngotonsillitis in ambulatory care – new recommendation]. Inf Läkemedelsverket. 2012;23(6):18–25.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sore throat (acute): antimicrobial prescribing 2018 www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng84.

Pelucchi C, Grigoryan L, Galeone C, Esposito S, Huovinen P, Little P, et al. Guideline for the management of acute sore throat. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(Suppl 1):1–28.

Shulman ST, Bisno AL, Clegg HW, Gerber MA, Kaplan EL, Lee G, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of group A streptococcal pharyngitis: 2012 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(10):1279–82.

Spinks A, Glasziou PP, del Mar CB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD000023.

Centor RM, Witherspoon JM, Dalton HP, Brody CE, Link K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1(3):239–46.

Facklam R. What happened to the streptococci: overview of taxonomic and nomenclature changes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(4):613–30.

Centor RM, Atkinson TP, Ratliff AE, Xiao L, Crabb DM, Estrada CA, et al. The clinical presentation of Fusobacterium-positive and streptococcal-positive pharyngitis in a university health clinic: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):241–7.

Hedin K, Bieber L, Lindh M, Sundqvist M. The aetiology of pharyngotonsillitis in adolescents and adults - Fusobacterium necrophorum is commonly found. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):263.

Gunnarsson RK, Manchal N. Group C beta hemolytic Streptococci as a potential pathogen in patients presenting with an uncomplicated acute sore throat—a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2020;38(2):226–37.

Marchello C, Ebell MH. Prevalence of group c streptococcus and fusobacterium necrophorum in patients with sore throat: a meta-analysis. Ann Family Med. 2016;14(6):567–74.

Malmberg S, Petren S, Gunnarsson R, Hedin K, Sundvall PD. Acute sore throat and Fusobacterium necrophorum in primary healthcare: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e042816.

Ludlam H, Howard J, Kingston B, Donachie L, Foulkes J, Guha S, et al. Epidemiology of pharyngeal carriage of Fusobacterium necrophorum. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58(Pt 9):1264–5.

Jensen A, Kristensen L, Prag J. Detection of Fusobacterium necrophorum subsp. funduliforme in tonsillitis in young adults by real-time PCR. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13(7): 695–701.

Riordan T. Human infection with Fusobacterium necrophorum (Necrobacillosis), with a focus on Lemierre’s syndrome. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(4):622–59.

Klug TE, Henriksen JJ, Rusan M, Fuursted K, Krogfelt KA, Ovesen T, et al. Antibody development to Fusobacterium necrophorum in patients with peritonsillar abscess. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(10):1733–9.

Dunn N, Lane D, Everitt H, Little P. Use of antibiotics for sore throat and incidence of quinsy. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(534):45–9.

Socialstyrelsen [The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare]. Klassifikation av sjukdomar och hälsoproblem 1997, Primärvård (KSH97-P) [Classification of diseases and health problems 1997, Primary healthcare] [Microsoft Excel file in Swedish and English]. 1996 [cited 2021 24 February]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/klassifikationer-och-koder/klassificering-kodtextfil-ksh97-primarvard-svensk-engelsk.xls.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12(10):e1001885.

Solvik UO, Boija EE, Ekvall S, Jabbour A, Breivik AC, Nordin G, et al. Performance and user-friendliness of the rapid antigen detection tests QuickVue Dipstick Strep A test and DIAQUICK Strep A Blue Dipstick for pharyngotonsillitis caused by Streptococcus pyogenes in primary health care. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;40(3):549–58.

Oliver J, Malliya Wadu E, Pierse N, Moreland NJ, Williamson DA, Baker MG. Group A Streptococcus pharyngitis and pharyngeal carriage: A meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(3):e0006335.

Frost HM, Fritsche TR, Hall MC. Beta-Hemolytic Nongroup A Streptococcal Pharyngitis in Children. J Pediatr. 2019;206(268–73):e1.

Shaikh N, Leonard E, Martin JM. Prevalence of streptococcal pharyngitis and streptococcal carriage in children: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;126(3):e557–64.

Little P, Gould C, Williamson I, Warner G, Gantley M, Kinmonth AL. Reattendance and complications in a randomised trial of prescribing strategies for sore throat: the medicalising effect of prescribing antibiotics. BMJ. 1997;315(7104):350–2.

Herz MJ. Antibiotics and the adult sore throat–an unnecessary ceremony. Fam Pract. 1988;5(3):196–9.

Little P, Williamson I. Sore throat management in general practice. Fam Pract. 1996;13(3):317–21.

Kyriacou DN, Lewis RJ. Confounding by Indication in Clinical Research. JAMA. 2016;316(17):1818–9.

Cars T, Eriksson I, Granath A, Wettermark B, Hellman J, Norman C, et al. Antibiotic use and bacterial complications following upper respiratory tract infections: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e016221.

Little P, Stuart B, Hobbs FD, Butler CC, Hay AD, Delaney B, et al. Antibiotic prescription strategies for acute sore throat: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(3):213–9.

Petersen I, Johnson AM, Islam A, Duckworth G, Livermore DM, Hayward AC. Protective effect of antibiotics against serious complications of common respiratory tract infections: retrospective cohort study with the UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2007;335(7627):982.

Powell EL, Powell J, Samuel JR, Wilson JA. A review of the pathogenesis of adult peritonsillar abscess: time for a re-evaluation. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(9):1941–50.

Sunnergren O, Swanberg J, Molstad S. Incidence, microbiology and clinical history of peritonsillar abscesses. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40(9):752–5.

van Driel ML, De Sutter AI, Habraken H, Thorning S, Christiaens T. Different antibiotic treatments for group A streptococcal pharyngitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD004406.

Pallon J, Sundqvist M, Hedin K. A 2-year follow-up study of patients with pharyngotonsillitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):3.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Olof Cronberg for assistance with data retrieval.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Lund University. This work was supported by Region Kronoberg, Sweden and The South Swedish Region Council. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Validation, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—review & editing. KH: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review & editing. MR: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. MS: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethics Review Board in Linköping, Sweden: 2016/529-31. All managers of the involved primary healthcare centres gave their permission to extract data, and these permissions were included in the application of ethical approval. As this study contains only retrospective anonymous patient data, the Regional Ethics Review Board in Linköping, Sweden, did not require informed consent from the patients. Confidentiality of the patients was ensured by using encrypted ID numbers.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Additional tables.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pallon, J., Sundqvist, M., Rööst, M. et al. Association between bacterial finding, antibiotic treatment and clinical course in patients with pharyngotonsillitis: a registry-based study in primary healthcare in Sweden. BMC Infect Dis 21, 779 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06511-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06511-y