Abstract

Background

Reports on the effects of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors on the clinical outcomes of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) have been conflicting. We performed this meta-analysis to find conclusive evidence.

Methods

We searched published articles through PubMed, EMBASE and medRxiv from 5 January 2020 to 3 August 2020. Studies that reported clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19, stratified by the class of antihypertensives, were included. Random and fixed-effects models were used to estimate pooled odds ratio (OR).

Results

A total 36 studies involving 30,795 patients with COVID-19 were included. The overall risk of poor patient outcomes (severe COVID-19 or death) was lower in patients taking RAAS inhibitors (OR = 0.79, 95% CI: [0.67, 0.95]) compared with those receiving non-RAAS inhibitor antihypertensives. However, further sub-meta-analysis showed that specific RAAS inhibitors did not show a reduction of poor COVID-19 outcomes when compared with any class of antihypertensive except beta-blockers (BBs). For example, compared to calcium channel blockers (CCBs), neither angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: [0.67, 1.23]) nor angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs) (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: [0.62, 1.33]) showed a reduction of poor COVID-19 outcomes. When compared with BBs, however, both ACEIs (OR = 0.85, 95% CI: [0.73, 0.99) and ARBs (OR = 0.72, 95% CI: [0.55, 0.94]) showed an apparent decrease in poor COVID-19 outcomes.

Conclusions

RAAS inhibitors did not increase the risk of mortality or severity of COVID-19. Differences in COVID-19 clinical outcomes between different class of antihypertensive drugs were likely due to the underlying comorbidities for which the antihypertensive drugs were prescribed, although adverse effects of drugs such as BBs could not be excluded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The effect of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors on the clinical outcomes of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) is of great interest [1]. This is because RAAS blockers, one of the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive drug groups, were previously reported to have some interactions with the pathophysiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1, 2].

Experimental studies have shown that blockage of RAAS by either angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARBs) substantially upregulates the expression of host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [3], a transmembrane enzyme used by SARS-CoV-2 as a receptor to enter and infect cells [4]. On the other hand, ACE2 catalyzes the degradation of potentially harmful angiotensin-II to a vasodilator angiotensin (1–7), which has antiarrhythmic and cardioprotective effects [2, 3]. In addition, RAAS inhibitors may also prevent some complications of COVID-19, such as hypokalaemia. Hence, despite concerns that overexpression of ACE2 with RAAS inhibitors could facilitate infection of tissues by SARS-CoV-2, these drugs could also have a therapeutic role.

Recent studies on the effects of RAAS inhibitors (ACEIs and ARBs) on the clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19 have reported conflicting results, ranging from a decrease in mortality [5, 6], no effect [7,8,9,10] or even an increase in mortality [11]. Even previous meta-analysis studies had conflicting findings that reported either a decrease [12,13,14] or an increase [15] in mortality with RAAS inhibitors. These varying effects on mortality may not be caused by the drugs themselves and could be related to the underlying comorbidities that guided the antihypertensive drug selection (e.g. beta-blockers (BBs) for a hypertensive patient with angina). This bias could partially be avoided by performing multiple sub-meta-analysis comparing one specific class of antihypertensive to another antihypertensive class. This permits a fair comparison of antihypertensive drugs with similar indication and helps us to keep compelling comorbidities in mind when comparing class of drugs with totally different indications (e.g. BBs for heart failure with systolic dysfunction versus thiazides for hypertension without this comorbidity [16]). As no prior meta-analysis made such analysis, we compared the of risk developing poor COVID-19 clinical outcomes among the five specific classes of antihypertensives: (ACEIs, ARBs, BBs, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and thiazides). In addition, this updated systematic review and meta-analysis included the most recent studies to estimate the overall risk of poor COVID-19 outcomes in patients receiving RAAS inhibitors compared to those receiving non-RAAS inhibitor antihypertensive agents.

Methods

This study was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 checklist [17] (Supplementary Table 1 (Table S1)).

Data sources and search terms

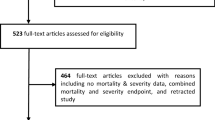

We searched PubMed, EMBASE and medRxiv preprint server to identify potentially relevant articles published between 5 January 2020 to 3 August 2020. A Google grey literature search was also performed to find additional articles that may have not been indexed. We used three main search keywords: (1) clinical outcome OR death OR mortality, (2) angiotensin and (3) COVID. These key words were combined with Boolean operators to make the following search term: (((((clinical outcome) OR death) OR mortality)) AND angiotensin) AND COVID. We found 339 and 604 articles indexed in PubMed and EMBASE, respectively (Fig. 1). We also found 498 articles from medRxiv preprint server and one article from manual search (Fig. 1). Two authors (Y. B., W. B.) selected studies by screening titles and abstracts. A third author (E. A) served as a mediator to reach a consensus for discrepancies.

Study definitions

RAAS inhibitors in this study refer to only ACEIs and ARBs whereas non-RAAS inhibitors include CCBs, BBs and thiazide diuretics. Severe COVID-19 refers to the presence of any of the following: respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/minute, oxygen saturation at rest ≤93%, oxygenation index [partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/ percentage of inspired oxygen (FiO2)] ≤300 mmHg, respiratory or other organ failure, mechanical ventilation, shock, or intensive care unit treatment [18]. We used the term ‘poor clinical outcome’ to indicate the presence of either severe COVID-19 or death. Main meta-analysis refers to the overall comparison of RAAS inhibitors to non-RAAS inhibitor drugs whereas sub-meta-analyses were comparison between specific class of drugs within the above two major groups of antihypertensives (e.g. ACEIs to CCBs).

Outcome of interest

The main outcome of interest was the overall risk of having poor clinical outcomes in patients infected with COVID-19 while receiving RAAS inhibitors, compared with those taking other antihypertensive agents. The secondary outcome was the risk of severe COVID-19 or death in patients receiving a specific RAAS inhibitor (e.g. ACEIs) compared with those receiving other classes of antihypertensives.

Study selection: inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that reported the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients stratified by class of antihypertensive drug therapy (treated group on RAAS inhibitors and control group on non-RAAS inhibitors) were included. Cohort (prospective or retrospective) studies, clinical trials, case series studies and editorials/letters that assessed COVID-19 clinical outcomes for patients taking RAAS inhibitors versus non-RAAS inhibitors were included. The included papers were either published (including preprint servers) or accepted original articles written in English. We excluded review papers and case reports. In addition, studies that compared COVID-19 clinical outcomes in two groups where the treated group were taking RAAS inhibitors whereas the control group were not taking any form of antihypertensive (e.g. hypertension requiring only dietary management) were ineligible. This was to have comparable groups in terms of the severity level of the comorbidity.

Data extraction and quality control

In each study, the total number of patients taking RAAS inhibitors or other class (es) of antihypertensives was recorded. Then, for each antihypertensive class exposure, the total number of patients with a poor clinical outcome (severe COVID-19 or death) versus those with a good outcome (non-severe COVID-19 and survival) were recorded. In addition, year, design of study and nature of comorbidities were also documented (Table 1).

The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) [50] was used for quality assessment of the included studies (Table S2). Two reviewers (W.B. and E.A.) independently performed the quality assessment and another author (Y.B.) brought consensus during discrepancies. Articles which got a score of less than 7 stars in the NOS were considered poor quality and excluded (Table S2).

Data analysis

A random-effects meta-analysis using the DerSimonian and Laird method [51] was used to estimate pooled odds ratio (OR) whenever the heterogeneity (I2) was above 25% and the fixed effects model (Mantel-Haenszel) was used when heterogeneity was ≤25%. A two-side alpha value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Publication bias was assessed using the funnel plot asymmetry. All analyses were performed using the OpenMeta (Analyst) [52].

Results

Study characteristics and quality assessment

A total of 1442 potentially relevant articles were identified through our search strategy. Of these, 36 articles were included in our final analysis (Fig. 2). All the included articles were of good quality (NOS score ≥ 7), and study characteristics and quality assessment are shown in Table 1 and Table S2, respectively.

A total of 30,795 COVID-19 patients were included. Among these, 19.6% (6036/30,795) of them had poor COVID-19 outcome. Majority of these patients (55% or 16,873/30,795) were taking non-RAAS inhibitors, whereas 45% (13,922/30,795) were receiving RAAS inhibitors. In most of the studies (22 of the 36 studies) patients taking antihypertensives were categorized based on the severity of COVID-19, whereas in the remaining 14 studies they were categorized based on survival after COVID-19 (Table 1). Eighteen studies compared RAAS inhibitors to non-RAAS inhibitors without mentioning of a specific antihypertensive sub-class whereas the remaining 18 studies documented the number of patients taking a specific drug class within the RAAS inhibitor and non-RAAS inhibitor drug groups. The latter group of studies that documented specific drug classes were eligible for sub-meta-analyses. In these studies, the total number of patients taking ACEIs (5145) and ARBs (5250) were comparable. In addition, the number of patients taking CCBs (3102), BBs (2792), and thiazides (1797) were approximately comparable (Table 1).

Comparison of the risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcomes with different antihypertensives

We found that the overall risk of poor patient outcomes was lower in patients taking RAAS inhibitors (OR = 0.79, 95% CI: [0.67, 0.95]) compared with those taking non-RAAS inhibitors (Fig. 2). Specific comparison of ACEIs to different antihypertensives including ARBs, CCBs, thiazides did not bring a decrease in poor outcomes among COVID-19 patients (Table 2, Supplementary Figures S1-S13). Similarly, comparison of ARBs to these class of drugs did not show a significant improvement in outcomes. For example, it is interesting to note that a comparison of ARBs to CCBs (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: [0.62, 1.33]) did not show difference in poor COVID-19 outcomes. However, comparison of either ACEIs or ARBs to BBs showed a decrease in poor COVID-19 outcomes (OR = 0.85, 95% CI: [0.73, 0.99]) and (OR = 0.72, 95% CI: [0.55, 0.94]), respectively.

Discussion

Evidence on the safety of antihypertensive medications is of paramount importance as about one-third of the world’s population is estimated to have hypertension [53] and this comorbidity is associated with increased mortality in patients with COVID-19 [54]. Since RAAS inhibitors were reported to affect the clinical outcome of COVID-19, either for good or worse [6, 11, 55], we pooled recent studies to provide stronger evidence on the effects of these drugs. In addition, we also performed multiple sub-meta-analyses (comparing class of antihypertensives) to identify the effect of specific drug classes. We found that COVID-19 patients taking RAAS inhibitors had an overall decreased risk of poor outcomes compared to those receiving non-RAAS inhibitors. However, based on our multiple sub-meta-analysis findings (Table 2), these effects were likely related to the underlying comorbidities for which specific antihypertensive class of drugs were indicated, and not necessarily related to the beneficiary role of RAAS inhibitors. In addition to compelling comorbidity, the adverse effects of drugs such as BBs could also be responsible.

It is possible that the overall decreased risk of COVID-19 severity or mortality with the use of RAAS inhibitors could be related to the blockage of a rapidly progressing systemic inflammation that is frequently seen in severe COVID-19 cases [56]. For example, COVID-19 patients taking ACE/ARBs had lower levels of inflammatory markers, such as interleukin 6 (IL-6) [9], C-reactive protein (CRP) and procalcitonin [10], than those not taking these drugs. In addition, these classes of drugs could also help prevent hypokalaemia, a complication that was reported to occur in COVID-19 patients [57]. Hence, RAAS inhibitors may decrease poor clinical outcomes by limiting the deleterious effects of angiotensin-II in multisystem inflammation, as well as by preventing the occurrence of hypokalaemia [56, 57]. Further, these drugs could also circumvent SARS-CoV-2 induced ACE2 downregulation in host cells, so that the preventive effects of ACE2 against severe disease are not lost [58].

However, the apparent decrease in COVID-19 poor outcomes with RAAS inhibitors could also be due to the mere comorbidity differences among patients who took different class of antihypertensive drugs. This is supported by our sub-meta-analyses findings that showed both ACEIs and ARBs were not different from CCBs in terms of COVID-19 outcomes (Table 2). Interestingly, however, ACEIs and ARBs showed a decrease in poor COVID-19 outcomes, when each were compared to BBs (Table 2). Therefore, the overall decrease in poor COVID-19 outcomes with RAAS inhibitors relative to non-RAAS inhibitors could be related to more severe cardiovascular comorbidity in patients taking certain non-RAAS inhibitors like BBs. Further, some adverse effects of BBs could be the cause of poor COVID-19 clinical outcomes.

In fact, a recent study showed that the use of either ACEIs or ARBs does not increase ACE2 expression in human tissues [59]. This is in sharp contrast to a previous experimental study (in rats) that reported an increase in ACE2 expression with these drugs [3]. Note that, increased ACE2 expression with the use of RAAS inhibitors was the key pathophysiologic process that was hypothesised to be associated with an increase in SARS-CoV-2 entry to human cells and hence diseases severity. On the other hand, increased ACE2 expression was also thought to be associated with a decrease in COVID-19 severity and mortality, since ACE2 enhances the degradation of harmful angiotensins into cardioprotective ones. Hence, combining all the above evidences, RAAS inhibitor antihypertensive medications might not have any effect at all on the severity or mortality of COVID-19.

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review and meta-analysis is a comprehensive one including the most recent studies and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 among patients taking major classes of antihypertensive drugs. However, our study has some limitations, majority of which are implicit to the studies included. First, even though all of the included papers were of good quality, propensity matching to address common confounders (e.g., age, comorbidity) was performed in only few of the studies. Second, the number of studies included in our sub-meta-analyses (versus the main meta-analysis) (Table 2) were relatively small and this might affect our conclusions. The other limitation is that our interpretation of sub-meta-analysis findings were based on our clinical judgement that assumed prescription of BBs could occur in patients with worse cardiovascular comorbidity [16]. For instance, patients taking certain antihypertensives like BBs may not necessarily have a worse cardiovascular condition. Similarly, even though ACEIs are good choice of antihypertensives in patients without any comorbidity, they are also preferred drugs in those who had myocardial infarction or systolic dysfunction. Finally, this review was not able to measure the clinical outcome of COVID-19 patients taking the combination of RAAS inhibitor and non-RAAS inhibitor drugs.

On the other hand, the strength of this meta-analysis is that we excluded studies that compared hypertensive patients who were taking RAAS inhibitors to those that were not taking any form of antihypertensive (e.g., on dietary management). This helped us to have comparable groups in terms of comorbidity and severity of hypertension.

Conclusion

An increased risk of severe COVID-19 or death was unlikely in patients receiving RAAS inhibitors (Fig. 2). Differences in COVID-19 poor outcomes were likely due to the underlying comorbidities for which the antihypertensive drugs were prescribed. COVID-19 should not bring a discontinuation or change in treatment with RAAS inhibitors as these antihypertensive drugs might not have any effect at all on the disease severity or mortality of COVID-19.

Abbreviations

- ACE2:

-

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- ACEI:

-

Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme inhibitors

- ARBs:

-

Angiotensin II receptor blockers

- BBs:

-

Beta blockers

- CCBs:

-

Calcium channel blockers

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-19

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- FiO2:

-

Percentage of inspired oxygen

- HTN:

-

Hypertension

- IL-6:

-

Interleukin 6

- mm Hg:

-

Millimetre of mercury

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PaO2:

-

Partial pressure of arterial oxygen

- RAAS:

-

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

References

Hanff TC, Harhay MO, Brown TS, Cohen JB, Mohareb AM. Is there an association between COVID-19 mortality and the renin-angiotensin system-a call for epidemiologic investigations. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020.

Danser AHJ, Epstein M, Batlle D. Renin-angiotensin system blockers and the COVID-19 pandemic: at present there is no evidence to abandon renin-angiotensin system blockers. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2020:HYPERTENSIONAHA12015082.

Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111:2605–10.

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020:S0092867420302294.

Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, Xie Y, Huang J, Li J, et al. COVID-19 with different severity: a multi-center study of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020:rccm.202002-0445OC.

Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J, Lei F, Qin J-J, Xie J, et al. Association of inpatient use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res. 2020:CIRCRESAHA.120.317134.

Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, Troxel AB, Iturrate E, Johnson SB, et al. Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020:NEJMoa2008975.

Li J, Wang X, Chen J, Zhang H, Deng A. Association of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors with severity or risk of death in patients with hypertension hospitalized for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1624.

Meng J, Xiao G, Zhang J, He X, Ou M, Bi J, et al. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors improve the clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients with hypertension. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:757–60.

Yang G, Tan Z, Zhou L, Yang M, Peng L, Liu J, et al. Effects Of ARBs And ACEIs On Virus infection, inflammatory status and clinical outcomes in COVID-19 patients with hypertension: a single center retrospective study. Hypertension. 2020:HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15143.

Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, Wu X, Zhang L, He T, et al. cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017.

Abdulhak AAB, Kashour T, Noman A, Tlayjeh H, Mohsen A, Al-Mallah MH, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers and outcome of COVID-19 : a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.05.06.20093260.

Qu G, Shu L, Song EJ, Verghese D, Uy JP, Cheng C, et al. Association between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers use and the risk of infection and clinical outcome of COVID-19: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.07.02.20144717.

Ghosal S, Mukherjee JJ, Sinha B, Gangopadhyay KK. The effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on death and severity of disease in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.04.23.20076661.

Nunes JPL. Mortality and use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in Covid 19 disease - a systematic review. medRxiv. 2020:2020.05.29.20116483.

Thomas U, Claudio B, Fadi C, Khan Nadia A, Poulter Neil R, Dorairaj P, et al. 2020 International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–57.

PRISMA. http://prisma-statement.org/prismastatement/Checklist.aspx. Accessed 30 Mar 2020.

Interpretation of "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Infection by the National Health Commission (Trial ... - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32033513. Accessed 17 May 2020.

Ip A, Parikh K, Parrillo JE, Mathura S, Hansen E, Sawczuk IS, et al. Hypertension and renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. medRxiv. 2020:2020.04.24.20077388.

Khera R, Clark C, Lu Y, Guo Y, Ren S, Truax B, et al. Association of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers with the risk of hospitalization and death in hypertensive patients with Coronavirus Disease-19. MedRxiv Prepr Serv Health Sci. 2020.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, Crawford JM, McGinn T, Davidson KW, et al. presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–9.

Tan N-D, Qiu Y, Xing X-B, Ghosh S, Chen M-H, Mao R. Associations between angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blocker use, gastrointestinal symptoms, and mortality among patients with COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1170–1172.e1.

Conversano A, Melillo F, Napolano A, Fominskiy E, Spessot M, Ciceri F, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and outcome in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: a case series study. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2020;76:e10–2.

Zhou X, Zhu J, Xu T. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with hypertension on renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Clin Exp Hypertens N Y N 1993. 2020;42:656–60.

Pan W, Zhang J, Wang M, Ye J, Xu Y, Shen B, et al. Clinical features of COVID-19 in patients with essential hypertension and the impacts of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors on the prognosis of COVID-19 patients. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2020;76:732–41.

Cannata F, Chiarito M, Reimers B, Azzolini E, Ferrante G, My I, et al. Continuation versus discontinuation of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers in COVID-19: effects on blood pressure control and mortality. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;6:412–4.

Lam KW, Chow KW, Vo J, Hou W, Li H, Richman PS, et al. continued in-hospital angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker use in hypertensive COVID-19 patients is associated with positive clinical outcome. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:1256–64.

Selçuk M, Çınar T, Keskin M, Çiçek V, Kılıç Ş, Kenan B, et al. Is the use of ACE inb/ARBs associated with higher in-hospital mortality in Covid-19 pneumonia patients? Clin Exp Hypertens N Y N 1993. 2020;42:738–42.

Amat-Santos IJ, Santos-Martinez S, López-Otero D, Nombela-Franco L, Gutiérrez-Ibanes E, Del Valle R, et al. Ramipril in high-risk patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:268–76.

Felice C, Nardin C, Di Tanna GL, Grossi U, Bernardi E, Scaldaferri L, et al. Use of RAAS inhibitors and risk of clinical deterioration in COVID-19: results from an Italian cohort of 133 hypertensives. Am J Hypertens. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpaa096.

Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, Xie Y, Huang J, Li J, et al. COVID-19 with different severities: a multicenter study of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:1380–8.

Yang G, Tan Z, Zhou L, Yang M, Peng L, Liu J, et al. Effects of angiotensin II receptor blockers and ACE (Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme) inhibitors on virus infection, inflammatory status, and clinical outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and hypertension: a single-center retrospective study. Hypertens Dallas Tex 1979. 2020;76:51–8.

Gao C, Cai Y, Zhang K, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Zhang X, et al. Association of hypertension and antihypertensive treatment with COVID-19 mortality: a retrospective observational study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2058–66.

Hu J, Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhao H, Lian J, Hao S, et al. COVID-19 is more severe in patients with hypertension; ACEI/ARB treatment does not influence clinical severity and outcome. J Infect. 2020;81:979–97.

Liu Y, Huang F, Xu J, Yang P, Qin Y, Cao M, et al. Anti-hypertensive Angiotensin II receptor blockers associated to mitigation of disease severity in elderly COVID-19 patients. 2020. https://medrxiv.org/cgi/content/short/2020.03.20.20039586. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

Zeng Z, Sha T, Zhang Y, Wu F, Hu H, Li H, et al. Hypertension in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A single-center retrospective observational study. 2020. https://medrxiv.org/cgi/content/short/2020.04.06.20054825. Accessed 23 Apr 2021.

Bravi F, Flacco ME, Carradori T, Volta CA, Cosenza G, De Togni A, et al. Predictors of severe or lethal COVID-19, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers, in a sample of infected Italian citizens. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0235248.

Dauchet L, et al. ACE inhibitors, AT1 receptor blockers and COVID-19: clinical epidemiology evidences for a continuation of treatments. ACER-COVID Study. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.28.20078071.

Feng Z, Li J, Yao S, Yu Q, Zhou W, Mao X, et al. The use of adjuvant therapy in preventing progression to severe pneumonia in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019: a multicenter data analysis. medRxiv. 2020:2020.04.08.20057539.

Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, Apolone G, Corrao G. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2431–40.

Yan H, Valdes AM, Vijay A, Wang S, Liang L, Yang S, et al. role of drugs used for chronic disease management on susceptibility and severity of COVID-19: a large case-control study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2020;108:1185–94.

Şenkal N, Meral R, Medetalibeyoğlu A, Konyaoğlu H, Kose M, Tukek T. Association between chronic ACE inhibitor exposure and decreased odds of severe disease in patients with COVID-19. Anatol J Cardiol. 2020;24:21–9.

Liabeuf S, Moragny J, Bennis Y, Batteux B, Brochot E, Schmit JL, et al. Association between renin–angiotensin system inhibitors and COVID-19 complications. Eur Heart J - Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020:pvaa062.

Sardu C, Maggi P, Messina V, Iuliano P, Sardu A, Iovinella V, et al. Could anti-hypertensive drug therapy affect the clinical prognosis of hypertensive patients with COVID-19 infection? Data from centers of Southern Italy. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;9. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.016948.

Liu X, Liu Y, Chen K, Yan S, Bai X, Li J, et al. Efficacy of ACEIs/ARBs vs CCBs on the progression of COVID-19 patients with hypertension in Wuhan: a hospital-based retrospective cohort study. J Med Virol. 2021;93:854–62.

López-Otero D, López-Pais J, Cacho-Antonio CE, Antúnez-Muiños PJ, González-Ferrero T, Pérez-Poza M, et al. Impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers on COVID-19 in a western population. CARDIOVID registry. Rev Espanola Cardiol Engl Ed. 2021;74:175–82.

Golpe R, Pérez-de-Llano LA, Dacal D, Guerrero-Sande H, Pombo-Vide B, Ventura-Valcárcel P. Risk of severe COVID-19 in hypertensive patients treated with renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Med Clínica. 2020;155:488–90.

Xu J, Huang C, Fan G, Liu Z, Shang L, Zhou F, et al. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers in context of COVID-19 outbreak: a retrospective analysis. Front Med. 2020:1–12.

Choi HK, Koo H-J, Seok H, Jeon JH, Choi WS, Kim DJ, et al. ARB/ACEI use and severe COVID-19: a nationwide case-control study. medRxiv. 2020:2020.06.12.20129916.

Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 17 May 2020.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88.

Wallace BC, Lajeunesse MJ, Dietz G, Dahabreh IJ, Trikalinos TA, Schmid CH, et al. Open MEE : Intuitive, open-source software for meta-analysis in ecology and evolutionary biology. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8:941–7.

Mills KT, Stefanescu A, He J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:223–37.

Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Zuliani G, Rigatelli A, Mazza A, Roncon L. Arterial hypertension and risk of death in patients with COVID-19 infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020:S0163445320301894.

Guzik TJ, Mohiddin SA, Dimarco A, Patel V, Savvatis K, Marelli-Berg FM, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1666–87.

Sun ML, Yang JM, Sun YP, Su GH. Inhibitors of RAS Might Be a Good Choice for the Therapy of COVID-19 Pneumonia. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi Zhonghua Jiehe He Huxi Zazhi Chin J Tuberc Respir Dis. 2020;43:E014.

Chen D, Li X, Song Q, Hu C, Su F, Dai J, et al. Hypokalemia and clinical implications in patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). medRxiv. 2020:2020.02.27.20028530.

Bourgonje AR, Abdulle AE, Timens W, Hillebrands J, Navis GJ, Gordijn SJ, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 ( ACE2 ), SARS-CoV -2 and pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID -19). J Pathol. 2020:path.5471.

Robust ACE2 protein expression localizes to the motile cilia of the respiratory tract epithelia and is not increased by ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers | medRxiv. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.08.20092866v1. Accessed 16 Aug 2020.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.B. and W.B.; methodology, Y.B. and W.B.; validation, Y.B., G.P., W. B, E.A. and A.B.; formal analysis, Y.B.; investigation, Y.B., W.B.; data curation, Y.B. and W.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.B.; writing—review and editing, Y.B., G.P., E.A., A.B.; visualization, Y.B., G.P., E.A., and A.B.; supervision, W.B.; project administration, W.B. and Y.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

PRISMA Checklist. Table S2. Quality score of articles (Newcastle–Ottawa Scale). Figure S1. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEIs relative to ARBs. Figure S2. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEIs relative to BBs. Figure S3. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEIs relative to CCBs. Figure S4. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEIs relative to thiazides. Figure S5. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEIs relative to all other antihypertensives. Figure S6. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ARBs relative to all other antihypertensives. Figure S7. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ARBs relative to BBs. Figure S8. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ARBs relative to CCBs. Figure S9. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ARBs relative to thiazides. Figure S10. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ARBs relative to all other non-RAAS antihypertensives. Figure S11. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEIs relative to all other non-RAAS antihypertensives. Figure S12. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with CCBs relative to ACEI, ARBs, BBs. Figure S13. Risk of poor COVID-19 clinical outcome with ACEI, ARBs, BBs relative to CCBs and thiazides.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bezabih, Y.M., Bezabih, A., Alamneh, E. et al. Comparison of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors with other antihypertensives in association with coronavirus disease-19 clinical outcomes. BMC Infect Dis 21, 527 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06088-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06088-6