Abstract

Background

Salmonellas enterica serovar Typhi (S.typhi) causes typhoid fever and is a global health problem, especially in developing countries like Ethiopia. But there is a little information about prevalence and factors association with S.typhi and its antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in Ethiopia especially in the study area.

The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of S.typhi infection, its associated factors and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among patient with a febrile illness at Adare General Hospital, Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods

Hospital based cross sectional study was conducted among 422 febrile patients from May 23, 2018 to October 20, 2018. A 5 ml venous blood was collected from each febrile patient. Culture and biochemical test were performed for each isolate. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed for each isolate using modified Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion techniques.

Result

In this study, the prevalence of S.typhi among febrile illness patients at Adare General Hospital was 1.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.5–2.9]. The age of the study subjects were ranged from 15 to 65 years (mean age 32 years). It was observed that participants who came from rural area had 8 times (AOR 8.27: 95% CI: 1.33, 51.55) more likely to had S. typhi infection when compared with urban dwellers. The microbial susceptibility testing revealed that all six of S.typhi isolates showed sensitive to Ceftriaxone and all 6 isolates showed resistant to nalidixic acid and Cefotaxime and 5(83.3%) susceptible to Chloramphenicol and Ciprofloxaciline. Multidrug resistance (resistance to three or more antibiotics) was observed among most of the isolates.

Conclusion

S. typhi bacteraemia is an uncommon but important cause of febrile illness in our study population. Ceftriaxone therapy is a suitable empirical antibiotic for those that are unwell and suspected of having this illness. Further surveillance is required to monitor possible hanging antibiotic resistant patterns in Ethiopia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Salmonella belongs to the family Enterobacteriaceae. Within two species, Salmonella bongori and Salmonella enterica, over 2500 different serotype or serovar have been identified [1]. The only known natural hosts and reservoir for S.typhi infections are low socioeconomic condition, deprived hygiene with human beings [2].. A very comparable but often less sever disease is caused by paratyphoid fever, which is caused by S.enterica serovar Paratyphoid A (SPA),B,C [3]. The organisms are non-capsulated, non-sporulating, gram negative, facultative anaerobic bacilli, which have characteristic flagellar, somatic and outer coat antigens [2].

Typhoid fever is a global health problem. It is an acute, life-threatening, febrile illness. Its real impact is difficult to estimate because the clinical picture is confused with those of many other febrile infections [3]. Without treatment, the case fatality rate of typhoid fever is 10–30%, however, an appropriate therapy may decreases the case fatality to 1–4% [4]. Despite the availability of antibiotics and different prevention method, almost 80% of the cases and deaths occur in Asia and the rest occur mostly in Africa and Latin America [5].

In many developing countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, the true burden of enteric fever is difficult to estimate due to the limited diagnostic resources and proper surveillance tools result in poor characterization of the burden of enteric fever [6, 7].

The global encumber of disease estimation for typhoid were estimated based on community-based incidence studies using climatic change and socio-economic features to derive continental estimates of the burden. In most African countries the recommended estimate incidence of typhoid were 10–100 cases/100,000 person years in most African countries with the incidence highest in childhood [8]. Because of the limited scope of studies, under-reporting of the case, the presence of other disease and lack of coordinated epidemiological surveillance system in Ethiopia it was difficult to evaluate the burden of typhoid fever infection [9].

In a study conducted in Jiggiga, Ethiopia the overall prevalence of enteric fever was 11%. The prevalence of S.typhi (7%) was higher than S.paratyphi (4%). The odds of having enteric fever were higher among the study participants aged 31–45 years and with previous history of enteric fever [10].

The risk for infection is high in low- and middle-income countries where typhoidal Salmonella is endemic and that have poor sanitation and lack of access to safe food and water [11] and the peak incidence is reported in children between 5 and 19 years of age in developing countries. But some studies in South Asia report highest rates of enteric fever under 5 years of age [12].

Access to safe water and sanitation is inadequate in many parts of the world. The scarcity of these basic amenities weighs heavily on public health and typhoid fever [13]. Regions with contaminated water supplies and inadequate waste disposal have a high incidence of typhoid fever [14].

Some patients excreting S.typhi have no history of typhoid fever which means they do not recollect a recent febrile illness with diahoea. Between 1 and 5% of patients with acute typhoid infection have been reported to become chronic carriers of the infection in the gall bladder, depending on age, sex and treatment regimen. The propensity to become a chronic carrier may have changed with the present availability and selection of antibiotics as well as with the antibiotic resistance of the prevalent strains [3].

In Ethiopia, as in other developing countries, the prevalence and real situation of antibiotic resistance is also not clear since Salmonella are not routinely cultured and their resistance to antibiotics cannot be tested. However, to control the spread of typhoid fever, surveillance for S.typhi and the assessment of antimicrobial susceptibility is essential [9]. Therefore; the aim of this research is to determine prevalence of S.typhi infection and its associated risk factor and its antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among patient with febrile illness.

Method

Study area

Hawassa town is the capital city of Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Regional state. The city is located on the shores of Lake Hawassa in the Great Rift Valley and is located 275 km to the South of Addis Ababa.

Study design and period

Hospital based cross sectional study was conducted from May 23, 2018 to October 20, 2018, at Adare General Hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

Study population

All febrile patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and requested for Widal test at Adare General Hospital, Hawassa, Ethiopia.

Inclusion criteria

The following patients who fulfilled all of the following criteria were included in the study:

1) Those who were febrile (defined as a temperature of 37 °C).

2) Those aged over 15 years old.

3) Those whom the treating physician suspected may have typhoid fever (demonstrated by the ordering of the “Widal test” with its’ known limitations.)

4) Those able and willing to consent to participation.

Exclusion criteria

The following patients were excluded from the study:

1) Those unable to consent to participation due to severity of illness.

2) Those who had received antibiotics within the 2 weeks prior to presentation.

3) Those presenting on more than one occasion during the study period had their first attendance included only.

Sample size determination

Sample size was calculated by using single proportion formula

Where n: sample size.

Z – Standard normal distribution value at the 95% CI, which is 1.96.

P – The prevalence was taken as, 50%.

d – The margin of error, taken as 5%.

Sample size = n (sample size) + (10% non-respondent).

Sample size (N) = 384 + 38.4= 421.4 ~ 422.

Samples collected during the study was 422.

Sampling technique and procedure

Systematic random sampling method was used to recruit patients attending outpatient department of Adare General Hospital. Considering a five month study period, an estimated of 1320 patients visited the outpatient department according to hospital plan and the past three months performance document review. This estimate was divided by the sample size to determine the sample interval (k value), which would be 3. The 1stserved patient was selected by lottery method and every 3rd patients thereafter were invited to participate in the study until the required sample size was obtained.

Data collection

A pre-tested and pre-structured questionnaire was used to collect information on socio-demographic characteristics (age, residence, marital status, and educational level) and associated factors (Additional file 1).

Culture and identification of S.typhi About 5 ml of venous blood sample was collected from each febrile patients and the sample was directly inoculated into bottle containing 45 ml triptic soya broth medium (Himedia,India) and incubated for 7 days. Those cultured bottle which showed growth were further sub cultured on MacConky agar (Deben diagnostic Ltd) and blood agar media (Biomark, India laboratories) after 48 h. Negative broth culture were incubated for seven days and sub cultured before reported negative. Suspected colonies obtained were screened by biochemical test using triple sugar iron agar (TSI), citrate utilization test, SIM (sulfide indole motility test), urease test and lysine decarboxylation test. Specific antisera were used to determine S.typhi.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test

Antimicrobial susceptibility test was done for the isolates of S.typhi using Muller-Hinton Agar (MHA) (Biomark, India laboratories) following the disk diffusion technique. Each isolate was tested for the selected antimicrobial agent such as ciprofloxacine (5 μg), cotrimoxazole (25 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (5 μg), nalidixic acid (30 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg) and ampicillin (10 μg) (Abetek biological Ltd). After incubation for 18–24 h at 37oc, 4–5 colonies was transferred to a tube containing 5 ml sterile normal saline by using inoculating loop. Turbidity of the broth was matched with 0.5 McFarland standards. A sterile cotton swab was dipped in to the suspension. The swab rotated and pressed firmly against the inside wall of the tube to remove excess inoculum. The swab was streaked on the surface of MHA and antibiotic disk were placed on the plate then the plate were incubated at 35-37oc for 18–24 h. The diameter of the zone of inhibition around the disk was measured using a metal caliper and the isolate were classified as sensitive, intermediate and resistant as recommended by CLSI 2018.

Quality assurance

The English version of the questionnaire has been converted to home language (Amharic) and reverses to English to make sure its uniformity by two individuals who have language professional and medical background (Additional file 1). Earlier to the commencement of data collection, every data collectors were taught by the principal investigator. The collected data were checked every day for reliability and truthfulness. Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) were rigorously pursued during sample collection, storage and analytical process. A pperformance test of the broth (internal quality control) has done by branded strain of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923. For quality control of blood agar Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 19604 and streptococcus pneumonia ATCC 49619 were used and for MacConkey, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Salmonellatyphimurium ATCC 13311 were used.

Data entry and analysis

Data entry, cleaning and analysis was done using SPSS version 23.0 software. First descriptive statistics was computed using frequency and percentage. The bivariate analysis was performed to select candidate variables for multivariate logistic regression analysis. Variables with p-value < 0.25 on bivariate analysis were selected for multivariate analysis. The final model was used to determine the association between explanatory variables and the outcome variables.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 422 study participant were enrolled in this study with an overall response rate 381 (90.28%). Of these, 172(45.1%) were males and 209(54.9%) were females. The mean age was 32 years and standard deviation (SD), 11.64; range, 15–65 years. Nearly, one-third of the study participants 136 (35.7%) were in the age category of 15–24 years. The majority of the study participants were urban 324 (85.3%) residence. Concerning the marital status 223(58.5%) were married and 208(54.6%) had completed secondary school and above (Table 1).

From the total study participants 367(96.3%) use tap water for drinking and 14(3.7%) uses river water, wall water or unprotected spring water for drinking purpose. Sixty one (16%) of the participants were treating water before drinking while 320(84%) were not use any treatment for drinking water (Table 2).

The availability of latrine among study participants were 379 (99.5%). The remaining had no latrine service. The hand washing habit of the study participants after latrine were 249(65.4%). Among them 97(39%) were using soap always, 100(40.2%) were sometimes and 52(20.9%) were not at all. From the total were respond latrine available in their home, while 2(0.5%) were respond no latrine in their home. From the total study subject were washes their hands after latrine. Among the study subject who were washes their hands, uses to washes their hands but uses soaps sometimes washing their hands after latrine, the rest were not use soap or only washes their hands with water (Table 2).

Prevalence of S.typhi

In this study, the overall prevalence of S.typhi were 1.6%.Additionally Staphylococcus aureus 25(6.56%). coagulase negative Staphylococci 20 (5.2%), E.coli 4(1%), Proteus spp. 2(0.5%), Enterococci 3(0.8%), Streptococci 3(0.8%), Klebseilla spp. 1(0.3%) and Pseudomonas spp. 1(0.3%) were observed.

The highest prevalence of S.typhi infection was observed among patients in the age group of 25–34 years old was 3(2.6%). Based on marital status, 1(7.1%) widowed and divorced patients were positive for S.typhi infection. With regard to site of residence, 7% of patients came from rural area were positive for S.typhi infection. Those patients with no formal education was 1(3.3%) for S.typhi and 2(2.5%) the students were positive for S.typhi (Table 1). The highest frequency of S.typhi infection were observed patient who were not washing hands after latrine 5(3.8%). (Table 2).

Associated factors for S.typhi infection

In the bivariate analysis, age, residence, marital status, hand washing practice, washing of vegetables or fruits before eating were candidate variable for multivariable analysis (Table 3).

In bivariate analysis, patient without hand washing practice after latrine were 9.76 times (COR 9.76: 95% CI: 1.13, 84.47, p=0.038) more likely to had S.typhi infection when compared with their counter parts. Study participants who did not washing of vegetables or fruits before eating were 3 times (COR: 95% CI: 0.55, 16.77, p=0.203) more likely to be infected with S.typhi infection even though, not statically significant.

In further analysis, after adjustment for those significantly associated variables using multivariable logistic regression analysis, the association between S.typhi infection and age,,marital status, handwashing practice after latrine and washing of vegetables or fruits before eating did not remain statistically significant (AOR 7.52; 95% CI 0.77–73.89, P = 0.083), (AOR 1.49; CI 0.23,9.87, P=0.675) respectively. In multivariable analysis, patients who came from rural area had 8 times (AOR 8.27: 95% CI: 1.33, 51.55) more likely to had S.typhi infection when compared with urban dwellers.

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern

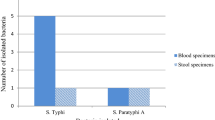

The susceptibility pattern of S.typhi isolated from blood culture against seven antimicrobial agent are presented in Fig. 1.The microbial susceptibility testing revealed that all 6(100%) of S.typhi isolates showed sensitivity to Ceftriaxone. All 6(100%) isolates showed resistant to Nalidixic acid and Cefotaxime and 5(83.3%) susceptible to Chloramphenicol and Ciprofloxaciline. Resistance to ampicillin was observed 83.3% of S.typhi MDR (resistance to three or more antibiotics) was observed among 83.3% (5 of 6) of S.typhi isolates (Table 4). The overall resistance for different antibiotics was ranged from 0 to 100%.

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of S.typhi among febrile illness patients at Adare General Hospital was 1.6% [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.5–2.9]. This finding was lower than study conducted in Shashemene Ethiopia 5% [15], Central Ethiopia (4.1%) [16], in Indonesia (15.5%) [17] and Lalitpur 4.1% [18]. Similar findings were also reported in India 2.5% [19] and Nepal 1.2% [20]. This difference might be due to geographic setting of the study district, the disparity in study population, time of the studies. Moreover, mode of the laboratory investigation technique disparity also have an effect on the result.

Regarding residence of study participants, it had significant association with S.typhi infection where patients living in rural area had 8 times higher risk of having S.typhi compared to those who live in urban area. This might be due to lack of access to safe water and hygienic edification, lack of toilet and/or hand washing exercise after toilet, open defecation practices near to the springs and rivers, insufficient medical care, low socio-economic status, poor personal hygiene are possible reason [21, 22].

S.typhi is one of the eight highly antibiotic resistant bacteria [23]. In our study all or 100 % of the isolates showed resistant to nalidixic acid. This finding was similar to the finding of Bangladesh and Nepal which shows 100 and 92% resistance, respectively to nalidixic acid [18, 24]. This augmentation may be due substandard supply, condensed antimicrobial therapy, medication sharing, fake drugs, bacterial advancement, climate changes and poor-quality drug.

In this study, most of the S.typhi isolates showed higher resistance to Ampicillin (83.3). This was similar to the study conducted in Kenya [25] and previous study done in Ethiopia [26] .This could be due to the availability and handling of these drugs from drug shops/pharmacy and lack of understanding in the management of antimicrobials.

The finding of this study shows all isolate of S.typhi were sensitive to ceftriaxone. Similar finding was reported in study done in Bangladesh and Lalitpure, Nepal which shows 100% sensitive to ceftriaxone [18, 23]. In this study chloramphenicol susceptible to S.typhi was observed, 83.3%. This finding was similar with study done in India which shows 87.4% of S.typhi was sensitive to Chloramphenicol [27].

Additionally, the episodes of S.typhi isolates resistant for more than two drugs were high (83.3%). The enhancement of this is possibly due to mobile genetic units (including plasmids, gene cassettes in integrons and transposons) [28], inadequate access to effective drugs, and abridged antimicrobial therapy [28, 29].

Limitations

The study was limited on small sample size, sensitivity /specificity and type of sample like stool.

Conclusion

Bacteraemeia with S.typhi was isolated in 6/379 (1.6%) of febrile patients in our study population. It is an important differential in unwell patients presenting to our hospital and should be considered alongside other bacteraemias seen in our setting, such as Staphylococcus aureus (seen in 25 patients, 6.56%), Enterococci (3 patients, 0.8%), and other gram negative organisms (E.coli, proteus, klebsiella, pseudomonas 8 patients, 2.1%.) This study confirms patients in our setting who are unwell with suspected typhoid fever should be treated empirically with Ceftriaxone intravenously. When available, antimicrobial sensitivity results should be used to guide decisions regarding oral antibiotic follow-on options (such as the use of cotrimazole or ciprofloxacin.) Ongoing surveillance is needed in Ethiopia to monitor changes in susceptibility patterns and to guide empirical treatment choices, to strengthen our antibiotic stewardship programmes and combat the rise of antimicrobial resistant pathogens.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

World Health Organization fact sheet salmonella (non typhoidal) reviewed September 2017.

Jasmine Kaur S.K.Jai:Role of antigens and virulence factors of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi in its pathogenesis;microbiological research Volume 167, Issue 4, 20 April 2012, Pages 199–210).

World Health Organization , Background document: The diagnosis, treatment and prevention of typhoid fever, Department of Vaccines and Biologicals CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland. 2003.

World Health Organization vaccine-preventable disese survillance standards 2014.

Ackers ML, Puhr ND, Tauxe RV, Mintz ED. Et a. laboratory-based surveillance of Salmonella serotype Typhi infections in the United States antimicrobial resistance on the rise. JAMA. 2000;283(20):2668–73.

Eng SK, Pusparajah P, Ab Mutalib NS, Ser HL, Chan KG, Lee LH. Salmonella: A review on pathogenesis, epidemiology antimicrobial resistance Journal Frontiers in Life Science. 2015 Volume 8(3 ):Pages 284–293.

Bharmoria A, Shukla A, Sharma K. Typhoid Fever as a Challenge for Developing Countries and Elusive Diagnostic Approaches Available for the Enteric Fever. Int J Vaccine Res. 2017;2(2):1–16.

Evanson M, English M. Typhoid fever in children in Africa. J Trop med and inter health. 2008;13(4):532–40.

Beyene G, Asrat D, Mengistu Y, Aseffa A, Wain J. Typhoid fever in Ethiopia. J Infect Develop Countries. 2008;2(6):448–53.

Dawit Admassu, Gudina Egata and Zelalem Teklemariam Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and Salmonella enterica serovar Paratyphi among febrile patients at Karamara Hospital, Jigjiga, eastern Ethiopia.

Crump JA, Karlsson MS, Gordon MA, Parry CM. Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Laboratory Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Antimicrobial Management of Invasive Salmonella Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(4):901–37.

Raveendran R, Datta S, wattal C. drug resistance in Salmonella enterica serotype typhi and paratyphi A. jimsa. 2010;vol. 23 (121).

Mogasale V, Maskery B, Ochiai RL, SeokLee J, Mogasale VV, Ramani E, et al. Burden of typhoid fever in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic, literature-based update with risk-factor adjustment. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(10):e570–e80.

Hosoglu S, Aldemir M, Akalin S, Geyik MF, Tacyildiz IH, Loeb M. Risk Factors for Enteric Perforation in Patients with Typhoid Fever. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;160(1):46–50.

Limenih Habte, Endale Tadesse, Getachew Ferede* and Anteneh Amsalu: Typhoid fever: clinical presentation and associated factors in febrile patients visiting Shashemene Referral Hospital, southern Ethiopia. BMC Res Note vol 11(605) 2018.

Andualem G, Abebe T, Kebede N, Gebre-Selassie S, Mihret A, Alemayehu H. A comparative study of Widal test with blood culture in the diagnosis of typhoid fever in febrile patients. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:653.

Mirari Prasada Judio1, Mulya Karyanti, Lia Waslia, Decy Subekti, Bambang Supriyatno, Kevin Baird: Antimicrobial Susceptibility among circulating S.typhi serotypes in Children in Jakarta, Indonesia Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Disease..

Kalpana Pandey,Vijay K. Sharma and Roshani Maharjan Prevalence and Antibiotic Sensitivity test of Salmonella Serovars from Enteric Fever Suspected Patients Visiting Alka Hospital, Lalitpur; American Journal of Microbiology 2015, 6 (2): 40.43 ).

Kumar S, Rizvi M, Berry N. Rising prevalence of enteric fever due to multidrugresistant Salmonella: an epidemiological study. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2008;57:1247–50.

Raza S, Tamrakar R, Bhatt CP, Joshi SK Antimicrobial Susceptibility Patterns of S.typhi and S.paratyphi A in a Tertiary Care Hospital : J Nepal Health Res Counc 2012 Sep;10(22):214–7).

Dewan AM, Corner R, Hashizume M, Onge ET. Typhoid fever and its association with environmental factors in the Dhaka Metropolitan Area of Bangladesh: a spatial and time-series approach. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(1):e1998.

Albert M. Vollaard, Soegianto Ali,Henri A. G. H. van Asten, Suwandhi Widjaja,Leo G. Visser,Charles Surjadi, Jaap T. van Dissel, Risk Factors for Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever in Jakarta, Indonesia: June 2, 2004 JAMA. 2004;291(21):2607–2615).

Globally TD-RI. Final report and recommendations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance Report. 2016.

Bulbul Hasan Sabera Gul Nahar Laila Akter Ahmed Abu Saleh; Antimicrobial sensitivity pattern of S.typhi isolated from blood culture in a referral hospital Bangladesh J Med Microbiol Volume 5: Number 1 January, 2011).

Mengo D, Kariuki S, Muigai A, et al. Trends in Salmonella enteric serovar Typhi in Nairobi, Kenya from 2004 to 2006. JInfect Dev Ctries. 2010;4(6):393–6.

Dagnew M, Yismaw G, Gizachew M, et al. Bacterial profile and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in septicemia suspected patients attending Gondar University hospital. BMC Res Notes: Northwest Ethiopia; 2013.

Tewari R, Jamal S, Dudeja M. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Salmonella enterica servars in southern Delhi. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2015 Aug;2(3):254–8.

Fewtrell L, Kaufmann RB, Kay D, Enanoria W, Haller L, Colford JM. Water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions to reduce diarrhoea in less developed countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(1):42–52.

Putnam S, Riddle M, Wierzba T, Pittner B, Elyazeed R, El-Gendy A, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility trends among Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. isolated from rural Egyptian paediatric populations with diarrhoea between 1995 and 2000. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10(9):804–10.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all data collectors and study participants whose contribution was vital throughout the data collection work. We would also acknowledge the southern Nation Nationalities people Hawassa public Health laboratory, and Adare Hospital for providing me all the support needed during data collection.

Funding

The study was supported by Hawassa University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences. The support included payment for data collectors, and purchase of materials and supplies required for the study. The support did not include designing of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RN: conceived and designed the study, performed the laboratory work, and analysing the data, involved in manuscript preparation. DYR: involved in protocol development and manuscript write up. DDG: conceived and designed the study, supervise the study, involved in analysis and manuscript preparation. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was ethically cleared from institutional Review Board (IRB) of the college of Medicine and Heath Sciences, Hawassa University (Ref No: IRB/179/10 dated on 03/05/2018). Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from hospital administration. The information sheet that contained about the benefit and risk of participating of the respondents in this study with verbal informed consent was attached to each questionnaire and before enrolled any of the eligible study participants, the purpose and the confidential nature of the study were described and discussed for each participant.

A written informed consent was obtained from participants whose age was greater than 16 and an assent form legal guardian or parent and additional consent were obtained from those less than 16 years old participants. Participants were anonymous and the information provided by each respondent was kept confidential. Also official permission and written informed consent was obtained from all parents/guardians for whom less than 16 years old.

Consent for publication

Not applicable as details, images and videos related to study subjects were not recorded for this study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Awol, R.N., Reda, D.Y. & Gidebo, D.D. Prevalence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi infection, its associated factors and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among febrile patients at Adare general hospital, Hawassa, southern Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis 21, 30 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05726-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05726-9