Abstract

Background

Increasing number of hospitalized children with community acquired pneumonia (CAP) is co-detected with Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp). The clinical characteristics and impact of Mp co-detected with other bacterial and/or viral pathogens remain poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the demographic and clinical features of CAP children with Mp mono-detection and Mp co-detection.

Methods

A total of 4148 hospitalized children with CAP were recruited from January to December 2017 at the Children’s Hospital of Hebei Province, affiliated to Hebei Medical University. A variety of respiratory viruses, bacteria and Mp were detected using multiple modalities. The demographic and clinical features of CAP children with Mp mono-detection and Mp co-detection were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Among the 110 CAP children with Mp positive, 42 (38.18%) of them were co-detected with at least one other pathogen. Co-detection was more common among children aged ≤3 years. No significant differences were found in most clinical symptoms, complications, underlying conditions and disease severity parameters among various etiological groups, with the following exceptions. First, prolonged duration of fever, lack of appetite and runny nose were more prevalent among CAP children with Mp-virus co-detection. Second, Mp-virus (excluding HRV) co-detected patients were more likely to present with prolonged duration of fever. Third, patients co-detected with Mp-bacteria were more likely to have abnormal blood gases. Additionally, CAP children with Mp-HRV co-detection were significantly more likely to report severe runny nose compared to those with Mp mono-detection.

Conclusion

Mp co-detection with viral and/or bacterial pathogens is common in clinical practice. However, there are no apparent differences between Mp mono-detection and Mp co-detections in terms of clinical features and disease severity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a leading cause of hospitalization among infants and children worldwide, especially in developing countries. A variety of respiratory viruses such as Influenza A (Flu A), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus (ADV) and human metapneumovirus (HMPV), and bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Hemophilus influenza, Staphylococcus aureus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) are associated with childhood CAP [1,2,3,4]. Notably, Mp accounts for 10–40% of CAP in children, and as high as 18% of cases with CAP require hospitalization [4,5,6]. In recent years, with the development more frequent use of molecular diagnostics, an increasing number of hospitalized CAP children are diagnosed with mixed viral-bacterial detections, and Mp co-detection is not uncommon [7,8,9,10]. However, the clinical characteristics and implications of Mp co-detection are poorly described.

To better characterize the impacts of Mp co-detection on CAP children, a 12-month prospective study was carried out to examine the demographic and clinical characteristics of CAP caused by Mp, including mono-detection and co-detection. In addition, this study assessed the differences in demographic and clinical features between mono- and co-detected CAP children.

Methods

Study population and case definitions

This prospective study was conducted on children (< 18 years) with CAP admitted at the Children’s Hospital of Hebei Province, affiliated to Hebei Medical University, China, over a period of 12 months (from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2017). The diagnostic criteria for CAP included: (a) clinical manifestations: fever, cough and/or dyspnea; (b) auscultatory findings: abnormal breath sounds, wheezes or crackles; and (c) radiographic evidence: consolidation, other infiltrate or pleural effusion.

CAP patients with positive results of Mp-DNA bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) or a ≥ 4-fold rise in IgG titer were considered to have Mp positive. If only Mp was detected, the patients were considered to have Mp mono-detection. Co-detection was defined as detection of Mp with ≥1 other bacterial or viral pathogen. Children with co-detection were stratified into two groups: Mp-virus co-detection and Mp-bacteria co-detection. The Mp-virus co-detection group was further stratified into two subgroups: Mp-HRV co-detection and Mp-virus (excluding HRV) co-detection.

Data collection

The demographic, clinical, laboratory and other related data of Mp-positive children were collected: (1) demographic characteristics: gender and age; (2) clinical information: duration of fever, cough, wheezing and gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea or vomiting); (3) laboratory results: peripheral leukocyte, neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, C-reactive protein (CRP) levels and chest radiographic findings; and (4) disease severity parameters: incidence of severe CAP [11], length of hospitalization, requirement for mechanical ventilation and admission to the PICU.

Specimen collection and laboratory testing

Blood, serum, nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) and BALF specimens were obtained for pathogen detection using multiple modalities.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for Mp-DNA detection in BALF specimens using a quantitative diagnostic kit (DaAn Gene Co. Ltd., Guangzhou, China) [12]. Serum IgG against Mp was evaluated by a commercial test kit (Virion-Serion, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Criteria for the diagnostic test were defined as IgG ≥4-fold titers [13].

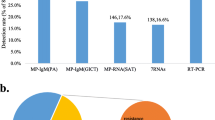

The NPAs collected from all patients were tested simultaneously for Flu A, Influenza B (Flu B), Influenza A H1N1 pdm09 (09H1), influenza H3N2 (H3), human parainfluenza virus (HPIV), RSV, rhinovirus (HRV), ADV, HMPV, human bocavirus (HBoV), human coronavirus (HCoV), Chlamydia (Ch) and Mp using a GeXP-based multiplex reverse transcription PCR assay [14]. The presence of bacteria and fungi was determined on admission by a positive result in blood specimen and/or BALF culture with the use of standard techniques.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 13.0.1 statistics package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). In brief, the demographic and clinical manifestations of all children with Mp positive were presented as absolute frequencies or rates for categorical variables, median (interquartile range) values for quantitative variables. Multiple sets of independent continuous data were compared using the Kruskale-Wallis test, while two sets of independent continuous data were compared by the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Pearson Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact Test. The level of statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Study population and microbiological diagnosis

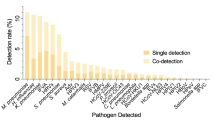

Between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017, 4148 patients who met the criteria of CAP were enrolled. Among them, 110 (2.65%) were defined as Mp positive (Table 1). Of these 110 patients, 68 (61.82%) were detected with only Mp, 42 (38.18%) were detected with at least one other pathogen, 30 (27.27%) were detected with one or more viruses, 7 (6.36%) were detected with one or more bacteria, and the remaining 5 (4.55%) were detected with both bacterial and viral pathogens (Table 2).

Demographic characteristics

Among the 110 patients with Mp positive, the median age was 5 years, which was significantly higher compared to that of 4148 CAP children (median age: 0.5 years, P < 0.001). Approximately 57.3% were male, and the gender distribution did not differ significantly between children with Mp positive and CAP (P = 0.094). Co-detection was more prevalent in children aged ≤3 year compared to those aged > 3 years old (64.29% vs. 29.27%; P = 0.001). The median age of CAP children with Mp-virus co-detection (P = 0.009), Mp-HRV co-detection (P = 0.004) and Mp-virus (excluding HRV) co-detection (P = 0.045) was significantly younger compared to those with Mp mono-detection (Table 3). Gender distribution did not differ significantly among various etiological groups (Table 3). The peak incidence of Mp detection was in autumn (October to November), while the peak incidence of Mp co-detection was in winter. Besides, Mp-virus co-detection and Mp-HRV co-detection occurred throughout the year, with no obvious seasonality. For Mp-bacteria co-detection, the highest incidence rates were observed in winter and spring (Fig. 1).

Clinical data, laboratory and radiographic findings

The differences in clinical data, laboratory and radiographic findings among various etiological groups are summarized in Table 4. Fever, cough, and sore throat were the three most common symptoms of children with Mp positive. In comparison with mono-detected patients, the duration of fever was significantly longer in Mp-virus co-detected (P = 0.039) and Mp-virus (excluding HRV) co-detected (P = 0.031) patients. Lack of appetite was more prevalent among children with Mp-virus co-detection (P = 0.022). Runny nose was more common in patients with Mp-virus co-detection (P = 0.012) and Mp-HRV co-detection (P = 0.002). However, the clinical features of patients with Mp-bacteria co-detection were relatively similar to those with Mp mono-detection. No significant differences were noted in terms of the laboratory and radiographic findings among various etiological groups.

Complications, underlying conditions and disease severity parameters

The differences in complications, underlying conditions and disease severity parameters among various etiological groups are presented in Table 5. All children with Mp positive, including Mp mono-detection and Mp co-detection, did not require PICU admission or invasive mechanical ventilation. However, the cases with severe CAP might require noninvasive mechanical ventilation, and the duration of hospitalization was not significantly different between the patients with Mp co-detection and Mp mono-detection. However, compared to those with Mp mono-detection, Mp-bacteria co-detected children were more likely to have abnormal blood gases (P = 0.041). In addition, the underlying medical conditions of Mp co-detected patients were relatively similar to those of Mp mono-detected patients.

Discussion

Mp has been recognized as a significant and common cause of pediatric CAP. In this study, it was found that 2.65% of hospitalized children with CAP experienced Mp positive, which is less than 19.1% reported in Wuhan, China [15]. Such low incidence may be attributed to the different study populations and methods used for Mp testing. Previous studies [16,17,18] have indicated that Mp is detected year-round, and its seasonal peaks have been reported in various seasonal periods starting from the end of summer to winter. In this study, Mp positive was more common in autumn, which is consistent with the findings of Chiu et al. [19].

At present, it is widely considered that mixed detections with multiple pathogens are common in children with CAP. Furthermore, Mp infection is often associated with preceding or concomitant viral and bacterial infections in children [19, 20]. In the present study, we found that children with co-detection accounted for 38.18% of total cases with Mp positive. This proportion is lower than that in Taiwan population [19] and higher than that in Beijing population [20]. However, the incidence of mixed detections with viruses was 27.27% in this study, which is higher compared to both Taiwan and Beijing populations. These differences may be due to the exclusion of HRV test in their studies. HRV is the most prevalent respiratory virus and is often associated with the common cold. Moreover, HRV may be associated with more severe lower respiratory tract infections in children, including bronchiolitis and pneumonia [21]. The results of this study showed that HRV was the most common pathogen among children with Mp co-detection, at a frequency of up to 18.18%. Thus, researchers and pediatricians should pay more attention to Mp-HRV co-detection among children with CAP. Age is an important factor that can affect pathogen distribution. The incidence of Mp infection is highest among children aged 3–7 years, while respiratory viral infections are more common in children younger than 2 years [22, 23]. Likewise, in this study, the patients with Mp-virus co-detections were significantly younger, especially prevalent among those ≤3 years old.

Mp-infected children can present with fever, cough, chest pain and wheeze, along with non-respiratory symptoms such as arthralgia and headache [24]. In the present study, we found that, similar to Mp mono-detection, fever, cough and sore throat were the three main symptoms of Mp co-detection, followed by non-respiratory symptoms, including rash, headache and abdominal pain. In addition, there were some differences in the clinical symptoms between patients with co-detection and mono-detection. First, compared to Mp mono-detection children, the duration of fever was significantly longer in children with Mp-virus and Mp-virus (excluding HRV) co-detection. Second, lack of appetite was more prevalent in children with Mp-virus co-detection. Third, runny nose was more common in patients with Mp-virus co-detection and Mp-HRV co-detection. However, the clinical symptoms are relatively non-specific, indicating that these parameters may not be helpful to distinguish Mp co-detection from Mp mono-detection.

A recent study shows that the clinical outcomes of Mp infection are heavily dependent on the co-infected pathogen [20]. Pientong et al. [25] have reported that Mp may serve as an important co-infectious agent of respiratory viruses, which increases the severity of acute childhood bronchiolitis. However, no significant differences were noted in the incidence of severe CAP, duration of hospitalization, and noninvasive mechanical ventilation among various etiological groups in the present study, suggesting that mixed detection of Mp with other viral or bacterial pathogen does not contribute to the severity of CAP. Chiu et al. [19] demonstrate that no significant difference is observed between the patients infected with Mp and those co-infected with virus, as similar to that reported in our study. To avoid overestimation of Mp-HRV co-detection, we further investigated the differences in clinical outcomes between children with Mp-virus (excluding HRV) co-detection and Mp mono-detection. Similarly, there was no significant difference between the two groups. Then, we further explored the role of Mp-HRV co-detection in children with CAP. Notably, a similar distribution of most complications, underlying conditions and disease severity parameters were found between the two groups. These results indicate that Mp-HRV co-detection may have little influence on the clinical outcomes of CAP. Likewise, we found no significant difference in the clinical outcomes between Mp-bacteria co-detection and Mp mono-detection, except that Mp-bacteria co-detection was more likely to be associated with abnormal blood gases. However, our results might differ from with the findings [19, 20] of different regions of China, suggesting that S. pneumoniae co-infection can lead to greater disease severity in children with Mp infection compared to single infection.

With the use of molecular diagnostics, co-detection with other viral/bacterial pathogens has been commonly identified in Mp positive patients. Nonetheless, this study confirms that the clinical features and severity of Mp mono-detected patients are relatively similar to those co-detected with viral and/or bacterial pathogens. Thus, we speculate that a large proportion of CAP patients may be infected with a major pathogen of pneumonia (i.e. Mp) and tend to have a colonization of other pathogens in respiratory tract [26]. Furthermore, it is also possible that the viral or bacterial pneumonia patients may have a serologic evidence of past MP infection (IgM positive) or PCR positive (colonization).

Nevertheless, this study has several limitations. The presence of co-infection should be confirmed by serologic tests at least 2 times during hospitalization or convalescent stage. However, it is very difficult to apply at clinical fields, owing to lack of available methods. In this study, due to the limits of current respiratory bacteria detection methods, the pattern of identified pathogens might not accurately represent the CAP, especially in young children. Moreover, the small sample size could impose restrictions on determining the association between Mp co-detection and disease severity. In addition, this single center study might not be representative of the entire Chinese pediatric population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we concluded that though Mp co-detection with viral and/or bacterial pathogens is common in clinical practice, there are no apparent differences between Mp mono-detection and Mp co-detections in terms of clinical features and disease severity. Our findings may eventually contribute to a better understanding of the implication of Mp co-detections in clinical practice, which is essential to improve preventive and therapeutic strategies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 09H1 :

-

Influenza A H1N1 pdm09

- ADV :

-

Adenovirus

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- Ch :

-

Chlamydia

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- Flu A :

-

Influenza A

- Flu B :

-

Influenza B

- H3 :

-

Influenza H3N2

- HBoV :

-

Human bocavirus

- HCoV :

-

Human coronavirus

- HMPV :

-

Human metapneumovirus

- HPIV :

-

Human parainfluenza virus

- HRV :

-

Rhinovirus

- Mp :

-

Mycoplasma pneumoniae

- NPAs:

-

Nasopharyngeal aspirates

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- RSV :

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

References

Cevey-Macherel M, Galetto-Lacour A, Gervaix A, Siegrist CA, Bille J, Bescher-Ninet B, Kaiser L, Krahenbuhl JD, Gehri M. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children based on WHO clinical guidelines. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:1429–36.

Don M, Fasoli L, Paldanius M, Vainionpää R, Kleemola M, Räty R, Leinonen M, Korppi M, Tenore A, Canciani M. Aetiology of community-acquired pneumonia: serological results of a paediatric survey. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:806–12.

Honkinen M, Lahti E, Österback R, Ruuskanen O, Waris M. Viruses and bacteria in sputum samples of children with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:300–7.

Jain S, Williams DJ, Arnold SR, Ampofo K, Bramley AM, Reed C, Stockmann C, Anderson EJ, Grijalva CG, Self WH, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization among U.S. children [J]. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(9):835–45.

Liu WK, Liu Q, Chen DH, Liang HX, Chen XK, Chen MX, Qiu SY, Yang ZY, Zhou R. Epidemiology of acute respiratory infections in children in Guangzhou: a three-year study [J]. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96674.

Ferwerda A, Moll HA, de Groot R. Respiratory tract infections by Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children: a review of diagnostic and therapeutic measures. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:483–91.

Juven T, Mertsola J, Waris M, Leinonen M, Meurman O, Roivainen M, Eskola J, Saikku P, Ruuskanen O. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in 254 hospitalized children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:293–8.

Michelow IC, Olsen K, Lozano J, Rollins NK, Duffy LB, Ziegler T, Kauppila J, Leinonen M, McCracken GH. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children. J Pediatr. 2004;113:701–7.

Chen CJ, Lin PY, Tsai MH, Huang CG, Tsao KC, Wong KS, Chang LY, Chiu CH, Lin TY, Huang YC. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia in hospitalized children in northern Taiwan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:e196–201.

Heiskanen-Kosma T, Korppi M, Jokinen C, Kurki S, Heiskanen L, Juvonen H, Kallinen S, Stén M, Tarkiainen A, Rönnberg PR, et al. Etiology of childhood pneumonia: serologic results of a prospective, population-based study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:986–91.

The Subspecialty Group of Respirology, the Society of Pediatrics, Chinese Medical Association. The editorial board of Chinese journal of pediatri. Guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in children (revised 2013). Chin J Pediatr. 2013;51(11):856–62.

Xu D, Li S, Chen Z, Du L. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in different respiratory specimens. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170(7):851–8.

Bradley JS, Byington CL, Shah SS, Alverson B, Carter ER, Harrison C, Kaplan SL, Mace SE, McCracken GH Jr, Moore MR, et al. The management of community-acquired pneumonia in infants and children older than 3 months of age: clinical practice guidelines by the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(7):e25–76.

Zhao M-c, Li G-x, Zhang D, Zhou H-y, Wang H, Yang S, Wang L, Feng Z-s, Ma X-j. Clinical evaluation of a new single-tube multiplex reverse transcription PCR assay for simultaneous detection of 11 respiratory viruses, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia in hospitalized children with acute respiratory infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;88:115–9.

Liu J, Ai H, Xiong Y, Li F, Wen Z, Liu W, Li T, Qin K, Wu J, Liu Y. Prevalence and correlation of infectious agents in hospitalized children with acute respiratory tract infections in Central China. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119170.

Luby JP. Pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Chest Med. 1991;12:237–44.

Johnson DH, Cunha BA. Atypical pneumonias. Clinical and extrapulmonary features of Chlamydia, Mycoplasma, and Legionella infections. Postgrad Med. 1993;93:69–72, 75–76, 79–82.

Lieberman D, Porath A. Seasonal variation in community acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2630–4.

Chiu C-Y, Chen C-J, Wong K-S, Tsai M-H, Chiu C-H, Huang Y-C. Impact of bacterial and viral coinfection on mycoplasmal pneumonia in childhood community-acquired pneumonia. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2015;48:51–6.

Song Q, Xu B-P, Shen K-L. Effects of bacterial and viral co-infections of mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: analysis report from Beijing Children’s hospital between 2010 and 2014. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(9):15666–74.

Louie JK, Roy-Burman A, Guardia-Labar L, Boston EJ, Kiang D, Padilla T, Yagi S, Messenger S, Petru AM, Glaser CA, et al. Rhinovirus associated with severe lower respiratory tract infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(4):337–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e31818ffc1b.

Youn YS, Lee KY, Hwang JY, Rhim JW, Kang JH, Lee JS, Kim JC. Difference of clinical features in childhood Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:48.

Liu XT, Wang GL, Luo XF, Chen YL, Ou JB, Huang J, Rong JY. Spectrum of pathgens for community-acquired pneumonia in children. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2013;15:42–5.

Harris M, Clark J, Coote N, Fletcher P, Harnden A, McKean M, Thomson A, British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. British thoracic society guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in children: update 2011. Thorax. 2011;66(Suppl 2):ii1–23.

Pientong C, Ekalaksananan T, Teeratakulpisarn J, Tanuwattanachai S, Kongyingyoes B, Limwattananon C. Atypical bacterial pathogen infection in children with acute bronchiolitis in Northeast Thailand. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2011;44:95–100.

Youn YS, Lee KY. Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. Korean J Pediatr. 2012;55(2):42–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Hebei Key Project Plan for Medical Science Research (20190834, 20180616, 20170402). The funding body had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MZ, GL and ZF conceived the study. MZ, LW and FQ performed the experiments. LZ, WG and SY conducted the clinical work. MZ wrote this article, ZF revised it. All the authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Children’s Hospital of Hebei Province, affiliated to Hebei Medical University. The written informed consent was obtained from each patient’s parent prior to enrollment.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, Mc., Wang, L., Qiu, Fz. et al. Impact and clinical profiles of Mycoplasma pneumoniae co-detection in childhood community-acquired pneumonia. BMC Infect Dis 19, 835 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4426-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4426-0