Abstract

Background

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluated the role of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prophylaxis of central venous catheter (CVC) related complications, but the results remained inconsistent, updated meta-analyses on this issue are warranted.

Methods

A meta-analysis on the RCTs comparing Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing versus other dressing or no dressing for prophylaxis of central venous catheter-related complications was performed. A comprehensive search of major databases was undertaken up to 30 Dec 2018 to identify related studies. Pooled odd ratio (OR) and mean differences (MDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using either a fixed-effects or random-effects model. Subgroup analysis was performed to identify the source of heterogeneity, and funnel plot and Egger test was used to identify the publication bias.

Results

A total of 12 RCTs with 6028 patients were included. The Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings provided significant benefits in reducing the risk of catheter colonization (OR = 0.46, 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.58), decreasing the incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) (OR = 0.60, 95% CI: 0.42 to 0.85). Subgroup analysis indicated that the Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings were conducive to reduce the risk of catheter colonization and CRBSI within the included RCTs with sample size more than 200, but the differences weren’t observed for those with sample less than 200. No publication bias was observed in the Egger test for the risk of CRBSI.

Conclusions

Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing is beneficial to prevent CVC-related complications. Future studies are warranted to assess the role and cost-effectiveness of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It’s very common that clinically indwelling central venous catheter (CVC) to meet the treatment needs, especially for patients admitted to intensive care unit (ICU) [1, 2]. The insertion of CVC provides credible pathway to meet the needs of rapid rehydration, the use of vasoactive drugs, hemodynamic monitoring and parenteral nutrition support, etc. [3]. However, the catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) may accompany with the use of CVC-related devices [4]. It’s been reported that the rate of CRBSI ranges from 0.8 to 0.2 per 1000 central-line catheter days [5, 6]. Besides, it’s well known that CRBSI leads to increased use of antibiotics, longer length of hospital stay, excessive burdens of healthcare costs and even higher mortality [7,8,9]. Therefore, effective strategies to prevent CRBSIs are essential to improve the prognosis of patients with CVC.

Currently, many CLABSI care bundles have been applied to prevent CRBSIs, which include highlighting hand hygiene, the maximum full-barrier precautions during the insertion process, and skin antisepsis etc. [10, 11]. In recent years, the use of Chlorhexidine for CRBSIs prevention has drawn numerous attentions from clinically health care providers. Many studies have reported the applications of Chlorhexidine in different ways, such as Chlorhexidine for bathing, disinfection, oral care and dressing-containing. Based on literature review, we found that several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluated and reported the role of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prophylaxis of CVC-related complications, but the results remained inconsistent and even controversial. Furthermore, currently the systematic reviews on the role of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prophylaxis of CVC-related complications are quite few. Besides, there are several new RCTs on this issue has been reported. Therefore, it’s necessary to conduct an updated meta-analysis to evaluate the role of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prophylaxis of CVC-related complications, thereby providing more evidences for the management of CVC.

Methods

This present systematic review was conducted and reported in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [12].

Search strategies

To identify potential eligible RCTs, a systematic literature search was conducted in following databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Science Direct, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang Database (from inception to 30 Dec 2018). Following search terms were used according to the rule of each database: “Chlorhexidine”, “dressing”, “sponge”, “bloodstream”, “infection”, “colonization”. The reference lists of articles were retrieved by two authors (L W and X L) and the authors of included RCTs were contacted to obtain additional data if necessary. Furthermore, the ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical TrialsRegistry Platform were manually searched for unpublished, planned or ongoing trial reports. And also the OpenGrey was manually searched to identify grey literature.

Criteria for included studies

RCTs comparing Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing versus other dressing or no dressing for prophylaxis of CVC-related complications were included irrespective of the language of publication, publication status, year of publication, or sample size.

Data extraction

Two authors (L W and Y L) independently evaluated the titles, abstracts and full-text of identified studies, any controversy was resolved by further discussion. The following data were collected for each included study whenever it’s available: authors, publication year, country of origin, study population, numbers of participants, type of inserted catheter, Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing intervention, definition of catheter colonization and CRBSI, outcome variables and study conclusions. The original authors were further contacted by email if there were something unclear. Two authors (L W and Y L) independently reviewed the included RCTs, and extracted and collected related data. All disagreements were resolved by further discussions.

Quality assessment

The Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [13] was used by two authors (L W and Y L) independently to evaluate the methodological quality and risk of bias of included RCTs; any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus.

Data analysis

The software RevMan 5.3 was used to perform statistical analyses in this present study. Binary outcomes were presented as Mantel–Haenszel-style odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI), and continuous outcomes were reported as mean differences (MDs). The presence of heterogeneity among trials was assessed by using chis-square test (p < 0.05 denoted statistical significance in the analysis of heterogeneity), whereas the degree of heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistic with a threshold of 50%, a random-effect or fix-effect model was used according to the degree of heterogeneity. The source of heterogeneity was detected by subgroup analysis, and the interaction was significant if the P value < 0.05 based on the sample size, effect size and 95% CI of each subgroup. Publication bias was evaluated by using funnel plots, and the asymmetry was assessed by conducting Egger regression test. Furthermore, we conducted sensitivity analyses to identify the impact of single study on the whole synthesized results. P < 0.05 was considered that the difference was statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

A total of 609 references were obtained from the initial electronic database searches. Eighteen additional references were identified from other sources. After de-duplication, 625 references were screened, and 588 reference were excluded after first screening on the title and abstract, thus 37 references underwent further full-text screening. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, finally 12 RCTs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25] were included. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flowchart for study selection.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of 12 included RCTs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Of the 12 included RCTs, a total of 6028 patients were involved, with 3242 patients for Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing intervention, and 2786 patients for other intervention respectively. The included RCTs were conducted in several different countries, one RCT [17] focused on the population of neonates, and one [18] focused on pediatrics, the resting RCTs were all conducted on adults. For the type of CVC, tunneled and non-tunneled CVC were both reported among the included RCTs. For Chlorhexidine intervention, the Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings were generally applied after catheterization and changed every 3 days. For observed outcomes, five studies [14, 18, 20, 21, 25] failed to detect the effects of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings on reducing the incidence of CRSBI or colonization, while the resting seven RCTs [15,16,17, 19, 22,23,24] favored that the Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings were beneficial to reduce the risk of CRSBI.

Risk of bias evaluation

Figures 2 and 3 indicate the risk of bias for each included study. Briefly, all included RCTs mentioned randomization in their reports, but two RCTs [16, 21] failed to report the methods to generate random sequence. Only two studies [14, 24] reported the methods to perform allocation concealment. All included studies were rated as high risk of performance bias as they were unable to blind the personnel or participant about the intervention allocated. Only one RCT [18] reported the blind design during the outcome assessment, thereby it was rated as low risk of detection bias. No other kinds of biases were found.

Effects of interventions

The risk of catheter colonization A total of seven RCTs [14, 17,18,19, 21, 23, 24] reported the risk of catheter colonization. The summary OR on the risk of catheter colonization between Chlorhexidine and control group was 0.46(95% CI, 0.36 to 0.58), without evident heterogeneity (P < 0.18, I2 = 33%) (Fig. 4a). The results indicated that Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings was beneficial to reduce the risk of catheter colonization.

The incidence of CRBSI A total of 11 RCTs [14,15,16,17,18,19,20, 22,23,24,25] reported the incidence of CRBSI. The summary OR on the incidence of CRBSI between Chlorhexidine and control group was 0.60(95% CI: 0.42 to 0.85), without evident heterogeneity (P = 0.22, I2 = 24%) (Fig. 4b). The results indicated that the Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings were conducive to reduce the incidence of CRBSI.

Subgroup analysis

We conducted subgroup analysis stratified by study size less or more than 200 patients, and the interactions were significant on the risk of catheter colonization and CRBSI when study size less or more than 200 patients (all P < 0.05), indicating that study size less or more than 200 patients is a potential influencing factor. As Fig. 5 showed, the Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressings provided more benefits in reducing the risk of catheter colonization and CRBSI among the included RCTs with sample size more than 200, but the differences weren’t observed among the included RCTs with sample size less than 200.

Publication bias

The funnel plot on the risk of catheter colonization is presented in Fig. 6, and even though the funnel plot was asymmetrical as it looked, but no publication bias was detected in the risk of CRBSI by Egger test (P = 0.071).

Sensitivity analysis

We excluded RCTs on each result one by one to see that if the overall results changed, and we found that the overall results weren’t changed by exclusion of any included RCTs.

Discussion

With 12 RCTs included, the results of this meta-analysis indicate that the use of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing is beneficial to reduce the risk of catheter colonization and CRBSI for patients with CVC, it’s an effective anti-infection strategy in preventing CRBSI. Our results are consistent with the previous findings of meta-analyses [26, 27], but with more RCTs included for synthesized analysis, our results do provide more strength in increasing the statistical effectiveness. As such, this study further supports the use of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prophylaxis of CVC-related complications.

Currently, several clustering care strategies in nursing care have been utilized to prevent CRBSI, such as the maximum sterile barriers, choosing appropriate location for insertion, disinfection of skin with Chlorhexidine, and daily assessment of the need for catheter removal etc. However, the results of published RCTs on Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing as a preventive strategy for CRBSI remain controversial. Based on literature reviews, the incidences of CRBSI varied greatly among different areas. The National Healthcare Safety Network reported that the CRBSI rates were 1.0‰~ 1.4‰ in adult ICUs of developed countries in 2010 [28], whereas International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium conducted a survey of 36 developing countries in Latin America, Asia, Africa and Europe, and it reported that the CRBSI rate was 6.8 ‰ [29]. The rate of CRBSI in China was 2.9 ‰~ 11.3‰ [30]. However, the overall rate of CRBSI in this present study is 11.5‰, which is higher than that of previous reports. Nevertheless, the rate of CRBSI in Chlorhexidine group is 15.2‰, yet the rate of CRBSI in control group is 26.3‰, a significant difference was detected between this two groups. Therefore, the application of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing is conducive to reduce the risk of CRBSI in patients with CVC.

Chlorhexidine gluconate is one kind of cationic surfactants, it’s commonly used for disinfecting skin or mucosal tissues clinically, the mechanism of Chlorhexidine gluconate for disinfection is that destroying the permeation barrier on bacterial cell membrane. At present, there are two kinds of Chlorhexidine dressings used clinically, one is one-piece, that is, the dressing itself is self-contained with Chlorhexidine, the other is a separate type, which needs to be covered with Chlorhexidine cotton, plus further transparent dressing covering. Pfaff [31] compared the effectiveness of a new one-piece occlusive dressing that incorporated Chlorhexidine gluconate with that of a dressing plus a Chlorhexidine gluconate patch, found that the new dressing provided more advantages in reducing the incidence of CRBSI, improving nurses’ satisfaction and saving medical cost. Additionally, since the dressings containing Chlorhexidine only need to be changed every 7 days, the frequency of dressing change reduces significantly when compared to the routine dressings requiring change every 3 days, thereby reducing the risk of infection and workload of nursing care [32, 33].

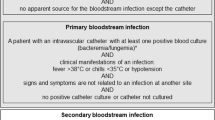

The definition, importance and potential relationship of colonization and CRBSI must be considered. Generally, the catheter is considered as being colonized when the culture of tip yield ≥15 colony-forming units of the same colony type, whereas CRBSI is defined as the presence of the same organism (identical species and anti-microbial susceptibility pattern) in a colonized PICC and in blood cultures from the same event [34]. Meanwhile, it’s been reported that cutaneous colonization is related to CRBSI [35]. There are some intersection in the definition of colonization and CRBSI, and the most included RCTs have both reported the colonization and CRBSI, yet the incidence of colonization and CRBSI varied greatly among the included RCTs, there is a possibility that making mistakes on mixing colonization and CRBSI, which is a potential source of result heterogeneity.

It should be highlighted that there are many factors influencing the incidence of CRBSI, which includes the site selection of CVC placement, the operation of catheterization, the maintenance after catheterization etc. [36,37,38] The Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing on the puncture site is only one related factors, more nursing care bundles must be considered in preventing CRBSI. Previous studies [39,40,41] have shown that the incidence of CRBSI is highest in the case of femoral vein catheterization, while the subclavian vein is the site with lowest incidence of CLABSI, and the internal jugular vein is the second. The aseptic techniques and the proficiency of operator during the catheterization are also closely related to CRBSI, repeated punctures can cause damage to the vessel wall and subcutaneous tissue, thereby increasing infection risk attributed to bacterial invasion [42, 43]. We attempted to conduct sub-group analysis according to catheter site, but the data on the catheter site among the included RCT were not fully available, future studies should focus on the role of catheter site and related nursing bundles in the management of CVC.

The cost of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing must also be concerned. It was reported that chlorhexidine-impregnated sponge use saved $197 by preventing infection per patient with the 3-day chlorhexidine-impregnated sponge dressing change strategy, and $83 with the 7-day standard dressing change strategy [44]. We attempted to compare the costs of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing with other dressing, however, only one RCT [25] reported this outcome, and this study [25] found that the use of Chlorhexidine transparent dressing could not save the direct economic cost of dressing, nor reduce length of ICU stay to save the indirect economic costs, but it could effectively reduce the frequency of dressing changes to ease the workload of nursing staff. Future studies are warranted to provide more insights into the economic evaluation on the use of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing.

Several limitations in this meta-analysis must be considered. Firstly, we didn’t use mesh terms in our search strategy or ask for help from a librarian developing the search strategy, therefore, there was possibility that some article might be missed in our initial search. Secondly, considering the nature of intervention, it’s rather difficult to blind the research personnel and outcome assessment, none of included RCTs was truly double blind design, hence the risk of bias is inevitable. And the blood culture was conducted in elected patients only among the included RCTs, this might also introduce bias. Thirdly, the rates of CRBSI among included RCTs varied greatly with a range of 0 to 11.3%, it might be related to the differences in clinical nursing practice and guidelines. Fourthly, the Egger test for the detection of publication bias was potentially underpowered given the small sample size, a non-significant Egger’s test did not necessarily suggest lack of asymmetry in the Funnel plot, therefore, this results should be treated with cautions. Finally, we only made post-hoc subgroup analyses stratified by sample size, but not by insertion location, type of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing, the frequency of dressing changes etc. due to the data limitation, the publication bias on the risk of catheter colonization remained unclear, future studies addressing the role of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing with combined consideration to those related factors are warranted.

Conclusions

In conclusions, the application of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing is effective in reducing the risks of catheter colonization and CRBSI for patients with CVC, which is beneficial to the prognosis of patients and it may be potentially worthy of clinical use. Future studies are needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing use and other related preventative strategies. Moreover, further stratified analysis of Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing use and CRBSI-related factors are needed to elucidate the optimal prophylaxes for CRBSI.

Abbreviations

- CIs:

-

confidence intervals

- CRBSI:

-

catheter-related bloodstream infection

- CVC:

-

central venous catheter

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- MDs:

-

mean differences

- ORs:

-

odd ratios

- PRISMA:

-

preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- RCTs:

-

randomized controlled trials

References

Gershengorn HB, Garland A, Kramer A, Scales DC, Rubenfeld G, Wunsch H. Variation of arterial and central venous catheter use in United States intensive care units. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(3):650–64.

Cho EE, Bevilacqua E, Brewer J, Hassett J, Guo WA. Variation in the practice of central venous catheter and chest tube insertions among surgery residents. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2018;11(1):47–52.

Brasher C, Malbezin S. Central venous catheters in small infants. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(1):4–5.

Huang V. Effect of a patency bundle on central venous catheter complications among hospitalized adult patients: a best practice implementation project. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16(2):565–86.

Salm F, Schwab F, Behnke M, Brunkhorst FM, Scherag A, Geffers C, Gastmeier P. Nudge to better care - blood cultures and catheter-related bloodstream infections in Germany at two points in time (2006, 2015). Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:141.

Hussein WF, Mohammed H, Browne L, Plant L, Stack AG. Prevalence and correlates of central venous catheter use among haemodialysis patients in the Irish health system - a national study. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19(1):76.

Saliba P, Hornero A, Cuervo G, Grau I, Jimenez E, Garcia D, Tubau F, Martinez-Sanchez JM, Carratala J, Pujol M. Mortality risk factors among non-ICU patients with nosocomial vascular catheter-related bloodstream infections: a prospective cohort study. J Hosp Infect. 2018;99(1):48–54.

Takeshita N, Kawamura I, Kurai H, Araoka H, Yoneyama A, Fujita T, Ainoda Y, Hase R, Hosokawa N, Shimanuki H, et al. Unique characteristics of community-onset healthcare- associated bloodstream infections: a multi-Centre prospective surveillance study of bloodstream infections in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2017;96(1):29–34.

Tribler S, Brandt CF, Fuglsang KA, Staun M, Broebech P, Moser CE, Scheike T, Jeppesen PB. Catheter-related bloodstream infections in patients with intestinal failure receiving home parenteral support: risks related to a catheter-salvage strategy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(5):743–53.

Lavallee JF, Gray TA, Dumville J, Russell W, Cullum N. The effects of care bundles on patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):142.

Arvaniti K, Lathyris D, Blot S, Apostolidou-Kiouti F, Koulenti D, Haidich AB. Cumulative evidence of randomized controlled and observational studies on catheter-related infection risk of central venous catheter insertion site in ICU patients: a pairwise and network meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):e437–48.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of intervention Version. 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Arvaniti K, Lathyris D, Clouva-Molyvdas P, Haidich AB, Mouloudi E, Synnefaki E, Koulourida V, Georgopoulos D, Gerogianni N, Nakos G, et al. Comparison of Oligon catheters and chlorhexidine-impregnated sponges with standard multilumen central venous catheters for prevention of associated colonization and infections in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):420–9.

Biehl LM, Huth A, Panse J, Kramer C, Hentrich M, Engelhardt M, Schafer-Eckart K, Kofla G, Kiehl M, Wendtner CM, et al. A randomized trial on chlorhexidine dressings for the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections in neutropenic patients. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(10):1916–22.

Chambers ST, Sanders J, Patton WN, Ganly P, Birch M, Crump JA, Spearing RL. Reduction of exit-site infections of tunnelled intravascular catheters among neutropenic patients by sustained-release chlorhexidine dressings: results from a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Hosp Infect. 2005;61(1):53–61.

Garland JS, Alex CP, Mueller CD, Otten D, Shivpuri C, Harris MC, Naples M, Pellegrini J, Buck RK, McAuliffe TL, et al. A randomized trial comparing povidone-iodine to a chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated dressing for prevention of central venous catheter infections in neonates. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1431–6.

Gerceker GO, Yardimci F, Aydinok Y. Randomized controlled trial of care bundles with chlorhexidine dressing and advanced dressings to prevent catheter-related bloodstream infections in pediatric hematology-oncology patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2017;28:14–20.

Levy I, Katz J, Solter E, Samra Z, Vidne B, Birk E, Ashkenazi S, Dagan O. Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prevention of colonization of central venous catheters in infants and children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24(8):676–9.

Pedrolo E, Danski MT, Vayego SA. Chlorhexidine and gauze and tape dressings for central venous catheters: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014;22(5):764–71.

Roberts B, Cheung D. Biopatch--a new concept in antimicrobial dressings for invasive devices. Aust Crit Care. 1998;11(1):16–9.

Ruschulte H, Franke M, Gastmeier P, Zenz S, Mahr KH, Buchholz S, Hertenstein B, Hecker H, Piepenbrock S. Prevention of central venous catheter related infections with chlorhexidine gluconate impregnated wound dressings: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Hematol. 2009;88(3):267–72.

Timsit JF, Schwebel C, Bouadma L, Geffroy A, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Pease S, Herault MC, Haouache H, Calvino-Gunther S, Gestin B, et al. Chlorhexidine-impregnated sponges and less frequent dressing changes for prevention of catheter-related infections in critically ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Jama. 2009;301(12):1231–41.

Timsit JF, Mimoz O, Mourvillier B, Souweine B, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Alfandari S, Plantefeve G, Bronchard R, Troche G, Gauzit R, et al. Randomized controlled trial of chlorhexidine dressing and highly adhesive dressing for preventing catheter-related infections in critically ill adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(12):1272–8.

Yu K, Li Z, Wang J, Li H, Lu M. Effect and cost analysis of two kinds of transparent dressings on the bloodstream infection rate of central venous catheter. Chin J Pract Nurs. 2015;31(36):2777–80.

Safdar N, O'Horo JC, Ghufran A, Bearden A, Didier ME, Chateau D, Maki DG. Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infection: a meta-analysis*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(7):1703–13.

Chen Y, Chen X, Zhuang Y, Guo F, Xu Q, Wu J, Qiao L, Li Q. Meta-analysis of the effect of chlorhexidine dressing on prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infection in adult ICU patients. Chin J Emerg Med. 2017;26(12):1461–4.

Edwards JR, Peterson KD, Mu Y, Banerjee S, Allen-Bridson K, Morrell G, Dudeck MA, Pollock DA, Horan TC. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) report: data summary for 2006 through 2008, issued December 2009. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(10):783–805.

Rosenthal VD, Maki DG, Jamulitrat S, Medeiros EA, Todi SK, Gomez DY, Leblebicioglu H, Abu Khader I, Miranda Novales MG, Berba R, et al. International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) report, data summary for 2003–2008, issued June 2009. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(2):95–104 e102.

Association TCCMBoCM. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of intravascular catheter-related infections (2007). Chin J Emerg Med. 2008;17(6):597–605.

Pfaff B, Heithaus T, Emanuelsen M. Use of a 1-piece chlorhexidine gluconate transparent dressing on critically ill patients. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(4):35–40.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, Craven DE, Flynn P, O'Grady NP, Raad II, Rijnders BJ, Sherertz RJ, Warren DK. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1–45.

Haque M, Sartelli M, McKimm J, Abu Bakar M. Health care-associated infections - an overview. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:2321–33.

Martin-Rabadan P, Perez-Garcia F, Zamora Flores E, Nisa ES, Guembe M, Bouza E. Improved method for the detection of catheter colonization and catheter-related bacteremia in newborns. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;87(4):311–4.

Laurenzi L, Natoli S, Benedetti C, Marcelli ME, Tirelli W, DiEmidio L, Arcuri E. Cutaneous bacterial colonization, modalities of chemotherapeutic infusion, and catheter-related bloodstream infection in totally implanted venous access devices. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(11):805–9.

Parienti JJ. Catheter-related bloodstream infection in jugular versus subclavian central catheterization. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(7):e734–5.

Kutsuna S, Hayakawa K, Kita K, Katanami Y, Imakita N, Kasahara K, Seto M, Akazawa K, Shimizu M, Kano T, et al. Risk factors of catheter-related bloodstream infection caused by Bacillus cereus: case-control study in 8 teaching hospitals in Japan. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(11):1281–3.

Pichitchaipitak O, Ckumdee S, Apivanich S, Chotiprasitsakul D, Shantavasinkul PC. Predictive factors of catheter-related bloodstream infection in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. Nutrition. 2018;46:1–6.

Ishizuka M, Nagata H, Takagi K, Kubota K. Femoral venous catheterization is a major risk factor for central venous catheter-related bloodstream infection. J Invest Surg. 2009;22(1):16–21.

Timsit JF, L'Heriteau F, Lepape A, Francais A, Ruckly S, Venier AG, Jarno P, Boussat S, Coignard B, Savey A. A multicentre analysis of catheter-related infection based on a hierarchical model. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(10):1662–72.

Timsit JF, Bouadma L, Mimoz O, Parienti JJ, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Alfandari S, Plantefeve G, Bronchard R, Troche G, Gauzit R, et al. Jugular versus femoral short-term catheterization and risk of infection in intensive care unit patients. Causal analysis of two randomized trials. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(10):1232–9.

Xia L, Guo X, Ye S, Wang M, Hong W. Risk factors for central venous catheter-associated infections and prevention countermeasures. Chin J Nosocomiology. 2014;38(12):3996–8.

Buchman AL, Opilla M, Kwasny M, Diamantidis TG, Okamoto R. Risk factors for the development of catheter-related bloodstream infections in patients receiving home parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2014;38(6):744–9.

Schwebel C, Lucet JC, Vesin A, Arrault X, Calvino-Gunther S, Bouadma L, Timsit JF. Economic evaluation of chlorhexidine-impregnated sponges for preventing catheter-related infections in critically ill adults in the dressing study. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):11–7.

Acknowledgments

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z W, M L and L W contributed to the conception and design of the research; L W, Z W, X L, and Y L contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data; X L, L W and L B contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data; Z W wrote the first draft of manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript, agree to be fully accountable for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the work, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, L., Li, Y., Li, X. et al. Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for the prophylaxis of central venous catheter-related complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 19, 429 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4029-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4029-9