Abstract

Background

Healthcare-associated infections have become a public health problem, creating a new burden on medical care in hospitals. The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria poses a difficult task for physicians, who have limited therapeutic options. The dissemination of pathogens depends on “reservoirs”, the different transmission pathways of the infectious agents and the factors favouring them. Contaminated environmental surfaces are an important potential reservoir for the transmission of many healthcare-associated pathogens. Pathogens can survive or persist in the environment for months and be a source of infection transmission when appropriate hygiene and disinfection procedures are inefficient. The aim of this study was to identify bacterial species from hospital surfaces in order to effectively prevent healthcare-associated infections.

Methods

Samples were taken from surfaces at the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi/So-Ava in South Benin (West Africa). To achieve the objective of this study, 160 swab samples of hospital surfaces were taken as recommended by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 14698-1). These samples were analysed in the bacteriology section of the National Laboratory for Biomedical Analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 21 software. A Chi Square Test was used to test the association between the Results of culture samples and different care units.

Results

Of the 160 surface samples, 65% were positive for bacteria. The frequency of isolation was predominant in Paediatrics (87.5%). The positive samples were 64.2% Gram-positive bacteria and 35.8% of Gram-negative bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus predominated (27.3%), followed by Bacillus spp. (23.3%).

The proportion of other microorganisms was negligible. S. aureus and Staphylococcus spp. were present in all care units. There was a statistically significant association between the Results of culture samples and different care units (χ2 = 12.732; p = 0.048).

Conclusion

The bacteria found on the surfaces of the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi/So-Ava’s care environment suggest a risk of healthcare-associated infections. Adequate hospital hygiene measures are required. Patient safety in this environment must become a training priority for all caregivers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare-associated infections (HAI) are a public health problem due to their high morbidity and mortality rates and subsequent economic consequences [1]. Pathogens responsible for these infections are varied and may have an endogenous or exogenous origin [2]. Despite advances in healthcare safety, the hospital environment can contribute to the spread of pathogens by transferring bacteria between patients and the environment [3]. Healthcare workers should be aware of the role of environmental contamination in the Intensive Care Unit and consider it in the broader perspective of infection control measures and stewardship initiatives [4]. Thus, pathogens can contaminate the surfaces of the hospital environment at concentrations sufficient for transmission from the hands of the nursing staff, or survive persist despite the disinfection of the environment [5]. Prior contamination of the patient environment is a factor in the acquisition of Healthcare-associated infections [6]. The microbial ecology of the care units remains a known risk factor for these infections [3].

In Benin, efforts are being made to fight healthcare-associated infections, but a study of patients admitted to a Benin hospital in 2012 reported a patient infection frequency of 9.84% [7]. In the fight against this health problem, it is important to carry out microbiological controls to identify the sources of pathogens in the hospital environment and with the infectious risk [8]. Therefore, knowledge of the microbiological contamination of the surfaces surrounding a patient provides information on the activity in the room, the presence of nosocomial pathogens and the quality of the disinfection [8, 9]. It is in this context that we aimed to determine the bacterial ecology on surfaces or even medical devices at the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi/So-Ava in South Benin (West Africa).

Methods

In order to identify the bacterial species contaminating the hospital environment, an analytical cross-sectional study was carried out on surface samples.

Study framework

This work spanned two months, from February to March 2017. It was carried out in the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi / So-Ava in South Benin (West Africa). CHUZAS has about 100 beds, and is located in a southern Benin city of a population of 656,358 inhabitants [10]. The samples were taken from various sites in the hospital environment, in various departments (surgery, maternity, paediatrics, medicine, emergency, operating theatre, recovery room). Bacteriological testing was carried out at the National Laboratory of Biomedical Analysis of the Ministry of Health (Benin).

Equipment

Conventional materials used in bacteriological diagnosis were used. Eosin Methylene-Blue (EMB), Chapman, Mueller Hinton Agar (MH) and API 20 E gallery were used.

Sample collection

The 160 samples were taken at different environmental sites according to the care units (Table 1). The areas sampled were: surgery tables; medical instrument tables; neonatal resuscitation tables, reusable electrosurgical patient plate, blood pressure cuff, oxygen mask, access door latches, care trolleys, patient examination tables, stethoscope pavilion, hospital bed sheets and the ground.

The samples were taken in the morning one hour after cleaning and disinfection of the room. For some care units (surgery room), the samples were taken after disinfection of the room without prior use. Swabs were taken according to ISO 14698-1 [11].

The sterile swabs were moistened with sterile distilled water and passed in parallel striations on the surface by turning them slightly, then in perpendicular striations on the same zones.

Subsequently, the swabs were returned to their protective cases and transmitted to the laboratory within one hour. We obtained a total of 160 samples from the 64 selected sites across the 7 investigative care units. The number of samples varied between 2 and 4 per site.

Isolation

The samples were emulsified in haemolysis tubes with 5 ml of Brain Heart broth (BHB) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Bacterial growth manifested in the form of turbidity. Each sample showing turbidity was streaked on Eosin Methylene-Blue, Chapman and MH medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Identification

Gram staining was carried out directly on one isolated colonies. One characteristic Colonies with Gram-negative bacilli (GNB), Gram-positive bacilli (GPB) and Gram-positive cocci (GPC) were then selected.

After purification, biochemical identification of GNB was carried out by seeding the API 20 E gallery. For the identification of S. aureus, catalase, coagulase and DNase tests were carried out on Gram-positive cocci. Catalase, oxidase, and urease tests were also performed on sporulate large Gram-positive bacilli for the identification of Bacillus spp.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 21 software. A Chi Square Test was used to test the association between the Results of culture samples and different care units.

Results

Result of samples

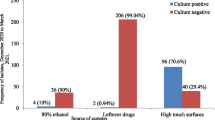

Of the total 160 samples analysed, 65% (n = 104) were positive for bacteria (Table 1).

The distribution by services is presented in Table 1. The greatest frequency of bacterial isolation was observed in paediatrics (87.5%) and the lowest proportion was found in the operating theatre (47.4%). There was a statistically significant association between the Results of culture samples and different care units (χ2 = 12.732; p = 0.048).

Biochemical identification

The study of biochemical characteristics revealed that of the total 150 species identified, 63.3% (n = 95) of the isolates were Gram-positive bacteria, and 55 36.7% (n = 55) were Gram-negative bacteria.

Distribution of gram-positive bacteria

Gram-positive bacteria consisted of 3 different species (Fig. 1). The most frequent were Staphylococcus aureus 27.3% (n = 41).

Distribution of bacterial species belonging to Enterobacteriaceae family

There were 4 genera that constituted 39 strains of bacteria from Enterobacteriaceae groupe identified in the study (Table 2).

The most frequent were Escherichia coli 7.3% (n = 11), followed by Serratia ficaria 5.3% (n = 08).

Distribution of non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli NFGNB

The Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacilli (NFGNB) strains consisted of 15 species. Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas oryzihabitans constituted 46.7% (n = 7) and 26.7% (n = 4), respectively (Fig. 2).

Repartition of species identified according to care units

Species identified in survey services are presented in Table 3. Staphylococcus aureus (23.3%) and Staphylococcus spp (12.7%) were present in all care units (Table 3).

Discussion

Antibiotic resistance is a health problem with the expansion of multidrug-resistant strains such as Klebsiella pneumoniae [12,13,14]. Surface swabs of various hospital care units were used for the identification of different bacterial species in this study. From a total of 160 hospital surface samples, there were 65% positive bacterial cultures. The share of negative bacterial cultures is the result of environmental contamination control through cleaning and disinfection. The air quality of the room is also important, because particles suspended in the air inevitably end up landing on the surfaces. There was a statistically significant association between the Results of culture samples and different care units (χ2 = 12.732; p = 0.048).

We identified a high percentage of positive cultures in paediatrics (87.5%), followed by medicine (75%) (Table 1). Presence of health teams and visitors in the care unit, and their consequent contact with different patients, objects and surfaces imply the possibility of pathogen dissemination if the necessary precautions (especially hand washing) are not observed. However, other means may be involved in the transference of pathogens [15, 16]. The distribution of the results obtained from the culture of the samples in this study, reflected the level of efficiency of the treatment of the air of certain care units (operating theatre) and the quality of the cleaning or the disinfection of the hospital surfaces in general. These data encourage a strengthening of the principles of cleaning and disinfection of hospital surfaces.

There were microbes on all surfaces analysed, with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus spp. present in all positive samples across all care units in our study (Table 3). The constant presence of these two species in all departments could also indicate a lack of hygiene in this hospital environment. We found S. aureus, which is a commensal microorganism and opportunistic pathogen [17], in 27.3% of samples (Fig. 1). The presence of S. aureus is not surprising because of its’ opportunistic and ubiquitous nature [18, 19]. Staphylococci survives for days on some surfaces [20].

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) can survive for days in the hospital environment; 12 days on a table, and 9 days on tissue [21]. In a study reported in 2015 by Ouendo et al. in Benin, 20% of the bacteria responsible for healthcare-associated infections were S. aureus [7]. The significant presence of S. aureus in the care environment of the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi / So-Ava in South Benin suggests the existence of infectious risk with the possibility of the appearance of methicillin-resistant strains.

Gram-negative bacilli (GNB) accounted for 36.7% (n = 55) in this study. Of the 150 species, Enterobacteriaceae accounted for 26.0%, followed by 15.0% NFGNB and 0.7% other GNB. Infections caused by GNB are specific because of the efficacy of these bacteria in the acquisition of genes that encode antibiotic resistance mechanisms [22]. In the hospital environment, these pathogens play an important role in the public health impact of healthcare-associated infections [23]. The detection rate of Enterobacteriaceae from all strains isolated in this study was 26.0%. This rate is comparable to the 23.5% obtained in 2007 in a hospital of Benin [24], and to the 25.03% reported in 2015 by a study in Tébessa (Algeria) in 2015 [25]. However, it was lower than the 67.33% obtained in 2008 on hospital environmental surfaces in Algeria [26]. These differences could be explained by the sample sizes.

In all 13 GNB genera isolated, there were Escherichia, Serratia and Pantoea. These genera can persist on dry surfaces for days [27]. In Enterobacteriaceae family, Escherichia coli 7.3% (n = 11) were the most frequent (Table 2). E. coli is a pathogen of healthcare-associated infections that poses problems in hospitals [28]. These include urinary tract infections, septicaemia, pneumonia, neonatal meningitis, peritonitis and gastroenteritis [17]. Escherichia coli ST131 est. un agent émergent résistant responsable d’infections des voies urinaires acquises dans la communauté et il est. important de contrôler sa propagation dans la communauté [29].

NFGNB are pathogenic bacteria with variable transmission capacities. Their identification at the species level is important for the management of patients suffering from healthcare-associated infections [30]. NFGNB are generally opportunistic pathogens that have been selected by repeated and prolonged antibiotic treatments [30]. In our study, Acinetobacter baumannii was the most frequently isolated NFGNB species at 46.7% (Fig. 2).

A. baumannii is an NFGNB present in the environment and commensal mucous membranes of man. This pathogen causes real therapeutic challenges because of its capacity to develop resistance to antibiotics [31,32,33]. The epidemic spread of A. baumannii is attributed to transmission on hands and to the prolonged survival of the microbe in the hospital environment [34]. This pathogen can persist from 3 days to 5 months [27], and survive under certain conditions for 4–5 months or more on dry surfaces [5]. The resistance of A. baumannii generates healthcare-associated infections with mortality up to 35% [35, 36].

Conclusion

Healthcare-associated infections are a significant public health problem. The pathogens responsible for these infections are often present on hospital surfaces and equipment. It is important to identify these bacterial species in order to effectively prevent Healthcare-associated infections. Here, we report the pathogens present in the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi /So-Ava in South Benin (West Africa). Some pathogens found evoke infectious risk and highlight the insufficiency of cleaning and the disinfection. Consequently, our results suggest an improvement in hospital hygiene and increased environmental disinfection is necessary.

Abbreviations

- API 20 E:

-

Apparatus and methods of identification for the 20 characters of enterobacteria

- BHB:

-

Brain heart broth

- EMB:

-

Eosin methylene-blue

- GNB:

-

Gram-negative bacilli

- GPB:

-

Gram-positive bacilli

- GPC:

-

Gram-positive cocci

- HAI:

-

Healthcare-associated infections

- ISO:

-

International organization for standardization

- MH:

-

Mueller hinton agar

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant s. aureus

- NFGNB:

-

Non-fermenting gram-negative bacilli

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social sciences

- UHC:

-

University hospital center

References

Defez C, Fbro-Peray P, Cazaban M. Additional direct medical cost of nosocomial infections: an estimation from a cohort of patients in a French university hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68:130–6.

Parneix P. Les infections nosocomiales associées aux soins. In: Hygiène hospitalière. Hygis N. Suramps Mecical. 2010;3:37–46.

Halwani M, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Grundmann H. Cross-contamination of nosocomial pathogens in an adult intensive care unit: incidence and risk factors. J Hosp Infect. 2006;63:39–46.

Russotto V, Cortegiani A, Fasciana T, Iozzo P, Raineri SM, Gregoretti C, Giammanco A, Giarratano A. What healthcare workers should know about environmental bacterial contamination in the intensive care unit. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:6905450.

Otter JA, Yelp S, French GL. The role played by contaminated surfaces in the transmission of nosocomial pathogens. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(7):687–99.

Drees M, Snydman DR, Schmid CH, Barefoot L, Hansjosten K, Vue PM, Cronin M, Nasraway SA, Golan Y. Prior environmental contamination increases the risk of acquisition of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(5):678–85.

Ouendo E-M, Saïzonou J, Dégbey C, Glélé Kakai C, Glélé Y, Makoutode M. Gestion du risque infectieux associé aux soins et services au Centre National Hospitalier et Universitaire Hubert Koutoukou Maga de Cotonou (Bénin), International Journal of Biological and Chemical. Sciences. 2015;9(1):292–300.

Van Der Mee-Marquet N. Surveillance et contrôle de l’environnement dans un établissement de santé In: Hygiène hospitalière. Hygis N. Suramps Mecical. 2010;3:257–64.

Galvin S, Dolan A, Cahill O, Daniels S, Humphreys H. Microbial monitoring of the hospital environment: why and how. J Hosp Infect. 2012;82(3):143–51.

INSAE Bénin, RGPH 4, 2013.

ISO 14698-1: 2003 (en). Cleanrooms and associated controlled environments Biocontamination control - Part 1: General principles and methods p32.

Bonura C, Giuffrè M, Aleo A, Fasciana T, Di Bernardo F, Stampone T, Giammanco A. MDR-GN working group, Palma DM, Mammina C. an update of the evolving epidemic of blaKPC carrying Klebsiella pneumoniae in Sicily, Italy, 2014: emergence of multiple non-ST258 clones. PLoS One. 2015;10:7.

Mammina C, Bonura C, Di Bernardo F, Aleo A, Fasciana T, Sodano C, Saporito M, Verde M, Tetamo R, Palma D. Ongoing spread of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in different wards of an acute general hospital, Italy, June to December 2011. Eur Secur. 2012;16(17):33.

Geraci DM, Bonura C, Giuffrè M, Saporito L, Graziano G, Aleo A, Fasciana T. F. Di Bernardo F, Stampone T, Palma DM, Mammina C. is the monoclonal spread of the ST258, KPC-3-producing clone being replaced in southern Italy by the dissemination of multiple clones of carbapenem-nonsusceptible, KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):15–7.

Wybo I, Blommaert L, De Beer T, Soetens O, De Regt J, Lacor P, Piérard D, Lauwers S. Outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a Belgian university hospital after transfer of patients from Greece. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67(4):374–80.

Comert FB, Kulah C, Aktas E, Ozlu N, Celebi G. First isolation of vancomycin-resistant enterococci and spread of a single clone in a university hospital in northswestern Turquey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;26(1):57–61.

Hassan AK, Aftab A, Riffat M. Nosocomial infection and their control strategies. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2015;5(7):509–14.

Nabila S e a, Adil E, Abedelaziz C, Nabila A, Samir H, Abdelmajid S. Rôle de l’environnement hospitalier dans la prévention des infections nosocomiales: surveillance de la flore des surfaces à l’hôpital El Idrissi de Kenitra- maroc. European Scientific Journal. 2014;9(10):238–47.

Subbalakshmi. Surveillance of Hospital Acquired Infection from Frequently Handled Surfaces in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. IntJCurrMicrobiolAppSci. 2018;7(02):860–6.

Neely AN, Maley MP. Survival of enterococci and staphylococci on hospital fabric and plastic. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:724–6.

Huang XZ, Frye JG, Chahine MA, Glenn LM, Ake JA, Su W, Nikolich MP, Lesho EP. Characteristics of plasmids in multi-drug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolated during prospective surveillance of a newly opened hospital in Iraq. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40360.

Ruppé E, Woerther PL, Barbier F. Mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance in gram-negative bacilli. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5:21.

Marty N. 2010. Les Flores de l’environnement humain In: Hygiène hospitalière. Hygis N. Suramps Mecical. 2010;3:26–36.

Ahoyo AT, Baba-Moussa L, Anago AE, Avogbe P, Missihoun TD, Loko F, Prévost G, Sanni A, Dramane K. Incidence d’infections liées à Escherichia coli producteur de bêta-lactamase à spectre élargi au Centre hospitalier département du Zou et Collines au Bénin. Med Mal Infect. 2007;37:746–52.

Debabza M. Emergence en milieu hospitalier des bacilles Gram négatifs multirésistants aux antibiotiques: étude bactériologique et moléculaire. In: Thèse de Doctorat en Microbiologie, Faculté des Sciences. Algérie: Université Badji Mokhtar-Annaba; 2015. p. 259.

Touati A, Brasme L, Benallaoua S, Madoux J, Gharout A, de Champs C. Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing CTX-M-15 recovered from hospital environmental surfaces from Algeria. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(2):183–5.

Kramer A, Schwebke I, Kampf G. How long do nosocomial pathogens persist on inanimate surfaces? A systematic review BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:130.

Lausch KR, Fuursted K, Larsen CS, Storgaard M. Colonization with multi-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in hospitalised Danish patients with a history of recent travel: a cross-sectional study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2013;11(5):320–30.

Fasciana, T., Giordano, G., Di Carlo, P., Colomba, C., Mascarella, C., Tricoli, M.R., Calà, C., Giammanco, A. Virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli ST131 in community-onset healthcare-associated infections in sicily, Italy. Pharmacologyonline. 2017; 1: Issue Special Issue, 12–21.

Ferroni A, Sermet-Gaudelus I, Abachin E, Quesnes G, Lenoir G, Berche P, Gaillard JL. Caractéristiques phénotypiques et génotypiques des souches atypiques de bacilles à Gram négatif non fermentant isolées chez des patients atteints de mucoviscidose. Pathol Biol. 2003;51:405–11.

Howard A, O'Donoghue M, Feeney A, Sleator RD. Acinetobacter baumannii. An emerging opportunistic pathogen Virulence. 2012;3(3):243–50.

Weber BS, Harding CM, Feldman MF. Pathogenic Acinetobacter: from the cell surface to infinity and beyond. J Bacteriol. 2015;198(6):880–7.

Mammina C, Palma DM, Bonura C, Aleo A, Fasciana T, Sodano C, Saporito MA, Verde MS, Calà C, Cracchiolo AN, Tetamo R. Epidemiology and clonality of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from an intensive care unit in Palermo. Italy BMC Research Notes. 2012;5:365.

Lahsoune M, Boutayeb H, Zerouali K, Belabbes H, El Mdaghri N. Prévalence et état de sensibilité aux antibiotiques d’Acinetobacter baumannii dans un CHU marocain. Med Mal Infect. 2007;37:828–31.

Antunes LC, Visca P, Towner KJ. Acinetobacter baumannii: evolution of a global pathogen. Pathogens and Disease. 2014;71(3):292–301.

Mammina C, Bonura C, Aleo A, Calà C, Caputo G, Cataldo MC, Di Benedetto A, Distefano S, Fasciana T, Labisi M, Sodano C, Palma DM, Giammanco A. Characterization of Acinetobacter baumannii from intensive care units and home care patients in Palermo, Italy. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(11):E12–5.

Acknowledgments

No additional acknowledgments.

Funding

This work did not receive any funding.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: FCDA; AJA, RCJ and HSB. Managed the conduction of the study: HSB; SCH. Collected samples: FCDA; AJA; OH. Microbiological advice and Microbiological analysis: AJA; OH. Analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript: RCJ; AJA; FCDA. All the authors were involved in the revision of the manuscript, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

We obtained a valid administrative authorization No. 188 /17 / MS / DDS-ATL-LIT / ZS-AS / CHUZ / SAAE / DGAP / SGA dated 24th January 2017, before taking samples from surfaces at the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi / So-Ava in South Benin (West Africa). No sample selected in this study for publication concerns humans. In the laboratory, protection and safety measures were guaranteed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Afle, F.C.D., Agbankpe, A.J., Johnson, R.C. et al. Healthcare-associated infections: bacteriological characterization of the hospital surfaces in the University Hospital of Abomey-Calavi/so-ava in South Benin (West Africa). BMC Infect Dis 19, 28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3648-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3648-x