Abstract

Background

The aim was to evaluate the value of organ-specific weighted incidence antibiogram (OSWIA) percentages for bacterial susceptibilities of Gram-negative bacteria (GNB) collected from intra-abdominal infections (IAIs) during SMART 2010–2014.

Methods

We retrospectively calculated the OSWIA percentages that would have been adequately covered by 12 common antimicrobials based on the bacterial compositions found in the appendix, peritoneum, colon, liver, gall bladder and pancreas.

Results

The ESBL positive rates were 65.7% for Escherichia coli, 36.2% for Klebsiella pneumoniae, 42.9% for Proteus mirabilis and 33.1% for Klebsiella oxytoca. Escherichia coli were mainly found in the appendix (76.8%), but less so in the liver (32.4%). Klebsiella pneumoniae constituted 45.2% of the total liver pathogenic bacteria and 15.2–20.8% were found in 4 other organs, except the colon and appendix (< 10%). The percentages of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections were higher in the gall bladder, intra-abdominal abscesses, pancreas and colon (10.2–13.2%) and least (5.4%) in the appendix. The susceptibilities of hospital acquired (HA) and community acquired (CA) IAI isolates from appendix, gall bladder and liver showed ≥80% susceptibilities to amikacin (AMK), imipenem (IPM), piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP) and ertapenem (ETP), while the susceptibility of isolates in abscesses and peritoneal fluid showed ≥80% susceptibility only to amikacin (AMK) and imipenem (IPM). In colon CA IAI isolates susceptibilities did not reach 80% for AMK and ETP, and in pancreatic IAIs susceptibilities of HA GNBs did not reach 80% to AMK, TZP and ETP, and CA GNBs to IMP and ETP. In addition, besides circa 80% susceptibility of HA and CA IAI isolates from appendix to cefoxitin (FOX), IAI isolates from all other organs had susceptibilities between 7.6 and 67.9% to all cephalosporins tested, 28.3–75.2% to fluoroquinolones and 7.6–51.0% to ampicillin-sulbactam (SAM), whether they were obtained from CA or HA infections.

Conclusion

The calculated OSWIA susceptibilities were specific for different organs in abdominal infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The massive over prescribing of antimicrobial agents has led to dramatic changes in clinical susceptibilities to antibiotics and multidrug-resistant (MDR) infection has been proven to be one of the major causes of mortality, especially those patients with IAIs [1, 2]. Mortality rates associated with secondary peritonitis and severe sepsis or septic shock average approximately 30%. [3, 4]

In 2012, Tabah et al. conducted a prospective, multicentre non-representative cohort study in 162 intensive care units (ICUs) in 24 countries, and showed that MDR and pan-drug-resistance (PDR) was increased in Europe, and Gram-negative bacterial infections were especially associated with an increased 28-day mortality [5]. Lack of effective initial empirical antimicrobial treatment within 24 h increases mortality significantly compared with appropriate antimicrobial treatment (63.0–65.2% vs 30.6–42.0%) [6, 7]. It has also been noted that effective empirical treatment needs to be supported by epidemiological studies and antimicrobial susceptibility data about the prevalence of local pathogenic bacteria. However, traditional epidemiological studies are limited to the description of the broad bacterial distributions and variable drug susceptibilities in individual hospitals, while detailed organ-specific data are usually lacking. Recently, Herbert et al. (2012) developed a novel method of displaying microbiology data to support early empirical antimicrobial treatments, which they termed the weighted-incidence syndromic combination antibiogram (WISCA). It classifies patients by syndrome and determines, for each patient with a given syndrome, whether a particular treatment regimen (one or more drugs) would have covered all the organisms recovered from their infections [8]. These data are calculated by dividing the number of the patients treated with a particular antimicrobial drug by the total number of patients. In the present study we created OSWIAs, which estimated the probability of organ specific isolates being susceptible to particular antibiotics.

Using data from the SMART study, we analyzed organ specific antimicrobial susceptibilities of Gram-negative bacteria in abdominal infections via OSWIA determinations in order to explore the practicability of this protocol and to assess its potential benefits in clinical practice in China.

Materials and methods

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital approved this study and waived the need for consent (Ethics Approval Number: SK238). Patient data were collected from a total of 21 hospitals in 16 Chinese cities from 2010 to 2014 and according to the SMART protocol each participating hospital provided at least 100 consecutive aerobic and facultative Gram-negative bacilli from patients with IAIs excluding duplicate isolates.

Isolates (8066) of Gram-negative aerobic bacteria and other pathogenic bacteria were obtained from different infected abdominal organs, including fermentative and non-fermentative bacteria in the appendix, peritoneum, colon, liver, gall bladder and pancreas from 2012 to 2014. All duplicate isolates (the same genus and species from the same patient) were excluded. Isolates collected within 48 h of hospitalization were categorized as community acquired (CA) IAIs, and those collected after 48 h were categorized as hospital acquired (HA) IAIs. The majority of intra-abdominal specimens were obtained during surgery, though some paracentesis specimens were also collected.

Bacterial identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Bacteria were identified by standard methods used in the participating clinical microbiology laboratories and all organisms were deemed clinically significant according to local criteria. All isolates were sent to the central clinical microbiology laboratory of Peking Union Medical College Hospital for re-identification using MALDI-TOF MS (Vitek MS, BioMérieux, France).

To assess antimicrobial susceptibilities, minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined with dehydrated MicroScan broth micro dilution panels (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, West Sacramento, CA, USA), according to the guidelines of the 2012 Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [9]. Susceptibility interpretations were based on the CLSI M100-S23 clinical breakpoints [10], and the ATCC 25922 strain of Escherichia coli (E. coli), the ATCC 27853 strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa), and the ATCC 700603 strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) were used as reference strains in each set of MIC tests for quality control. The antibiotics tested were the aminoglycoside amikacin (AMK), the carbapenems ertapenem (ETP) and imipenem (IPM), the cephamycins cefoxitin (FOX), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefepime (FEP), cefotaxime (CTX) and ceftriaxone (CRO), the fluoroquinolones levofloxacin (LVX) and ciprofloxacin (CIP) as well as the broad spectrum penicillins combined with β-lactamase inhibitors ampicillin-sulbactam (SAM) and piperacillin-tazobactam (TZP).

Phenotypic identification of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) positive bacteria were carried out by CLSI recommended methods [10]. If MICs were ≥ 2 μg/mL for cefotaxime or ceftazidime, the MICs of cefotaxime or ceftazidime plus clavulanic acid (4 μg/mL) were determined and ESBL production was defined as a ≥ 8-fold decrease of MICs for cefotaxime or ceftazidime plus clavulanic acid.

Organ-specific weighted incidence antibiogram (OSWIA) calculation

We evaluated the data retrospectively and analyzed the pathogenic bacteria distribution in various abdominal organs. OSWIAs were calculated using the following equation: Weighted susceptibility of a certain antimicrobial drug in a certain organ = antimicrobial susceptibility of A × the constituent ratio of A in the organ + antimicrobial susceptibility of B × the constituent ratio of B in the organ + antimicrobial susceptibility of C × the constituent ratio of C in the organ + (where A, B, C represent the pathogenic bacteria in a certain organ).

Statistical analysis

The susceptibility of all Gram-negative isolates combined was calculated using breakpoints appropriate for each species and assuming 0% susceptibility for species with no breakpoints for any given drug. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the adjusted Wald method; linear trends of ESBL rates in different years were assessed for statistical significance using the Cochran-Armitage test and comparison of ESBL rates were assessed using a chi-squared test. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Distribution of gram-negative enteric bacteria from 2010 to 2014

The majority if IAI isolates included E. coli, with 3764 strains in total (46.7%), of which 2472 (65.7%) were ESBL-producing strains, followed by K. pneumoniae with 1486 strains in total (18.4%) of which 538 (36.2%) were ESBL-producing strains. Other major pathogenic bacteria included 804 strains of P. aeruginosa (10.0%) and 558 strains of Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) (6.9%), which both belong to the non-fermentative bacteria group, as well as 410 strains of Enterobacter cloacae (E. cloacae) (5.1%). The rest of the pathogenic bacteria comprised < 2% of the total. The majority of non-fermentative GNBs was isolated from HA IAIs (Table 1). A total of 61 other strains were rarely isolated and detailed information is listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparison of the pathogenic distribution of abdominal infections in different organs (2010–2014)

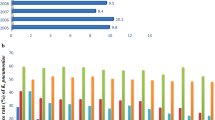

In Figure 1, we show the pathogenic distribution of Gram-negative bacteria in some infected organs in the abdomen, including 2510 strains from the gall bladder (31.1%), 2078 strains from peritoneal fluid (25.8%), 1444 strains from abdominal abscesses (17.9%), and the remainder from the appendix (405 strains), colon (174 strains), liver (553 strains) and pancreas (256 strains), respectively.

The majority of the abdominal pathogenic bacteria included fermentative bacteria comprising E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and the non-fermentative bacteria A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa. The highest percentage of E. coli was found in the appendix (76.8%) and the least percentage in the liver (32.4%). K. pneumoniae accounted for 45.2% of the total pathogenic bacteria in the liver and moderate fractions (15.2–20.8%) in the gall bladder, peritoneal fluid, abscesses and pancreas, but only 7.7% in the appendix and 5.7% in the colon. P. aeruginosa was one of the major pathogens found in the gall bladder (11.5%), abscesses (10.2%), pancreas (12.2%) and colon (13.2%). The highest percentage of A. baumannii was found in the pancreas (11.0%) and the least percentage in the appendix (≤ 1%) (Fig. 1).

Non-fermentative GNBs accounted for 12.5% of liver and 6.7% of appendix infections, whereas the percentages in other organs were 18.8–25.8%. More non-fermentative bacteria were found in HA compared to CA infections in all abdominal organs except the appendix. In pancreas infections, the ESBL producing rates of Enterobacteriaceae were slightly higher in HA compared to CA IAIs, but in the liver the GNB rate was almost double. There were obvious differences between Enterobacteriaceae ESBL producing rates within the organs, being highest in the colon followed by the pancreas and peritoneal fluid infections (Table 2).

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of specific syndromes determined by OSWIAs in IAIs.

Next, we calculated the OSWIAs (Fig. 2). Additionally, apart from the liver, all other organs presented with a typical “stair-step” shape, with only AMK, IPM, TZP and ETP susceptibilities being ≥80%; the rest of the antibiotics had activity far below this level. The highest susceptibility rates to AMK, IMP, TZP and ETP were found in he appendix and differences between HA and CA IAI susceptibilities were more pronounced in the colon, peritoneal fluid and pancreas, being higher in CA derived strains from peritoneal fluid and pancreas but less in CA strains isolated from colon infections. Apart from susceptibility of appendix isolates to FOX, IAI isolates from all other organs were susceptible (18–74.5% to all cephalosporins tested including cefoxitin, whether they were obtained from CA or HA infections, suggesting a high prevalence of ESBL production. Susceptibilities to fluoroquinolones were 28.3–75.2% and to SAM 7.6–51.0% (Fig. 2).

Discussion

A timely worldwide multi-center cross-sectional study showed that abdominal infections constituted 19.6% of infected patients in ICUs. The mortality of patients was higher than those with other infections (29.4% vs 24.4%, P < 0.001). Nearly all patients were treated with antibiotics (98.1%), but the results of microbial culture were obtained in only about two-thirds of patients [11]. The common use of empirical antimicrobial drugs needs to refer to local epidemiological studies and antimicrobial susceptibility data [12]. Traditional epidemiological studies are conducted in a “bacteria-antibiotics” mode, which first describes the isolated local bacteria strains, then reports the corresponding drug susceptibilities. In 2012, Herbert et al. proposed that WISCAs could determine the likelihood that a specific regimen can effectively treat all organisms in a patient with a specific syndrome after microbial and clinical data analysis [8]. This method is based on significant differences in the distribution of pathogenic bacteria sites, which is usually lacking in traditional microbial/epidemiological studies; thus, the patients cannot be treated precisely.

In addition, OSIWA estimates for empirical therapies of IAIs might serve as an initial hint for the choice of antibiotics when other information is not available, since bacterial strain identification and antibiograms requires some time to produce the data, particularly for IAIs.

SMART is a global multi-center abdominal infection program that mainly monitors Gram-negative bacteria and their susceptibility to antibiotics. The data showed that Enterobacteriaceae were still the major strains found in abdominal infections (2010–2014) in China, the most common types being E. coli and K. pneumoniae, which is in agreement with a previous study [13].

Other non-fermentative bacteria include P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii, which accounted for 10.0 and 6.9% of pathogens, respectively. A. baumannii were not commonly detected in general abdominal infections, but its distribution rate was high in certain organs such as the pancreas. According to our analyses, the composition of pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria isolated from the abdominal cavity is different, based on the isolation sites. For example, Gram-negative E. coli bacteria from the appendix accounted for 76.8%, but was distributed < 40% in the liver and pancreas. K. pneumoniae accounted for 45.2% of the total pathogenic bacteria in the liver but < 6% in the colon, which is in line with previous reports that liver infections caused by K. pneumoniae are increasing [14, 15].

Therefore, the distribution of pathogenic bacteria in different abdominal organs should be considered in empirical therapy. We further analyzed comprehensive antimicrobial susceptibilities using the OSWIA algorithm, which is calculated according to the susceptibility of each bacterium to a specific drug times the sum of the total proportion of the bacterium present in a specific infection. We found that OSWIA closely matched the clinical data: compared with pancreatitis and other infection sites, appendicitis had a higher overall antimicrobial susceptibility. Additionally, the susceptibility rates for liver and gall bladder infections was somewhere in between, but it should be noted that the therapeutic effects of antimicrobial drugs can be highly variable when treating different infected organs.

Let’s consider OSWIA > 80% as the initial gold standard. For example, the OSWIA of FOX is around 80% in the appendix, but was < 70% in the other 5 organs examined. Thus, it would only be appropriate for the treatment of specific infections in the appendix. Piperacillin/tazobactam (TZP) is recommended to treat many infections, but OSWIA was only 68.3% in HA pancreas infections, which is inappropriate for empirical treatment. Additionally, we found that apart from liver infections, the weighted susceptibility for each abdominal organ presented as a typical “stair-step” shape, with some of drugs such as ertapenem, amikacin, imipenem and piperacillin/tazobactam being > 80%, and the rest far below this level. The weighted susceptibilities of ertapenem, amikacin, imipenem and piperacillin/tazobactam were highest in all organs, which is in line with another study on Chinese IAIs [13].

ESBL rates of Enterobacteriaceae essentially differed between organs (Table 2), which were reflected in the low susceptibility rates to cephalosporins of colon, pancreas and peritoneal fluid isolates (Fig. 2). The high proportion of ESBL-producing strains in the pathogens of the studied organs certainly indicate a high risk for Chinese IAI patients becoming infected with an ESBL producing bacterial strain.

We analyzed the epidemiological data of antimicrobial susceptibilities using an “organ–bacteria–susceptibility” approach, but still a large number of clinical factors could not be included in the analysis, including the drug concentrations at the infection sites and the physical condition of individual patients.

Moreover, drawbacks in our data analysis have been noted. First, a classification based on infected organs reduced the sample size in each group, which decreased the reliability of the statistical analysis, and Gram-negative anaerobes and Gram-positive bacteria were not included. Second, because of the limited strain numbers in each year, we combined data from several years, which might not reflect the actual situation in each year. Yearly OSWIA analysis with sufficient samples should be conducted in large hospitals, as a complement to the traditional model of “bacteria-susceptibility” to support appropriate regimen selection of antibiotics for empirical therapy.

Conclusions

There are significant variations in the distributions of bacteria in different abdominal organs, with various antimicrobial organ-specific susceptibilities. OSWIA may be used as a complement to the traditional model of “bacteria–susceptibility”, and aid appropriate regimen selection of antibiotics for empirical therapy, particularly for CA IAIs. However, further studies will need to be conducted to validate the correlations between OSWIA, and the cure and survival rates of patients.

Abbreviations

- ETP:

-

(ertapenem)

- AMK:

-

(amikacin)

- IPM:

-

(imipenem)

- TZP:

-

(piperacillin/tazobactam)

- FOX:

-

(cefoxitin)

- CAZ:

-

(ceftazidime)

- LVX:

-

(levofloxacin)

- FEP:

-

(cefepime)

- CIP:

-

(ciprofloxacin)

- CRO:

-

(ceftriaxone)

- CTX:

-

(cefotaxime)

- SAM:

-

(ampicillin/sulbactam)

References

Paterson DL, Rossi F, Baquero F, Hsueh PR, Woods GL, Satishchandran V, Snyder TA, Harvey CM, Teppler H, Dinubile MJ, et al. In vitro susceptibilities of aerobic and facultative gram-negative bacilli isolated from patients with intra-abdominal infections worldwide: the 2003 study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends (SMART). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;55(6):965–73.

Superti SV, Augusti G, Zavascki AP. Risk factors for and mortality of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli nosocomial bloodstream infections. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2009;51(4):211–6.

Sartelli M. A focus on intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2010;5:9.

Weigelt JA. Empiric treatment options in the management of complicated intra-abdominal infections. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74(Suppl 4):S29–37.

Tabah A, Koulenti D, Laupland K, Misset B, Valles J, Bruzzi de Carvalho F, Paiva JA, Cakar N, Ma X, Eggimann P, et al. Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: the EUROBACT international cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(12):1930–45.

Garnacho-Montero J, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Barrero-Almodovar A, Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Perez-Paredes C, Ortiz-Leyba C. Impact of adequate empirical antibiotic therapy on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(12):2742–51.

Valles J, Rello J, Ochagavia A, Garnacho J, Alcala MA. Community-acquired bloodstream infection in critically ill adult patients: impact of shock and inappropriate antibiotic therapy on survival. Chest. 2003;123(5):1615–24.

Hebert C, Ridgway J, Vekhter B, Brown EC, Weber SG, Robicsek A. Demonstration of the weighted-incidence syndromic combination antibiogram: an empiric prescribing decision aid. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):381–8.

CLSI: Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically; Approved Standards. 9th ed. Document M07-A: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, Penn.; 2012.

CLSI: Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-third informational supplement. Document M100-S23 clinical and laboratory standards institute, Wayne, Penn.; 2013.

De Waele J, Lipman J, Sakr Y, Marshall JC, Vanhems P, Barrera Groba C, Leone M, Vincent JL, Investigators EI. Abdominal infections in the intensive care unit: characteristics, treatment and determinants of outcome. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:420.

Zhang S, Huang W. Epidemiological study of community- and hospital-acquired intraabdominal infections. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18(2):84–9.

Zhang H, Yang Q, Liao K, Ni Y, Yu Y, Hu B, Sun Z, Huang W, Wang Y, Wu A, et al. Update of incidence and antimicrobial susceptibility trends of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Chinese intra-abdominal infection patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):776.

Liu Y, Wang JY, Jiang W. An increasing prominent disease of Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:258514.

Siu LK, Yeh KM, Lin JC, Fung CP, Chang FY. Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: a new invasive syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(11):881–7.

Acknowledgments

Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD; Whitehouse Station, NJ, US) provided funds to support this study.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are directly available from MSD China Holding Co. Ltd., but the SMART database is not public. Data are also available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of MSD China Holding Co. Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both of the authors listed have read and approved the manuscript. The authors were solely responsible for the conception and performance of the study and for writing the manuscript. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Shanghai BIOMED Science Technology (Shanghai, China) through funding provided by MSD China. The authors were solely responsible for the conception and performance of the study and for the contents and the writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Human Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital approved this study and waived the need for consent (Ethics Approval Number: SK238).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. A total of 61 IAI isolates were collected in < 0.2% of the Enterobacteriaceae or < 1.1% of non-fermentative bacterial strains. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Ni, Y. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of specific syndromes created with organ-specific weighted incidence antibiograms (OSWIA) in patients with intra-abdominal infections. BMC Infect Dis 18, 584 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3494-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3494-x