Abstract

Background

Talaromyces marneffei (T. marneffei) is a thermal dimorphic pathogenic fungus that often causes fatal opportunistic infections in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients. Although T. marneffei-infected cases have been increasingly reported among non-HIV-infected patients in recent years, no cases of T. marneffei infection have been reported in pulmonary sarcoidosis patients. In this case, we describe a T. marneffei infection in an HIV-negative patient diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old Chinese man who had pre-existing pulmonary sarcoidosis presented with daily hyperpyrexia and cough. Following a fungal culture from bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), the patient was diagnosed with T. marneffei infection. A high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) chest scan revealed bilateral lung diffuse miliary nodules, multiple patchy exudative shadows in the bilateral superior lobes and right inferior lobes, air bronchogram in the consolidation of the right superior lobe, multiple hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies and local pleural thickening. After 3 mos of antifungal therapy, the patient’s pulmonary symptoms rapidly disappeared, and the physical condition improved markedly. A subsequent CT re-examination demonstrated that foci were absorbed remarkably after treatment. The patient is receiving follow-up therapy and assessment for a cure.

Conclusion

This case suggested that clinicians should pay more attention to non-HIV-related lung infections in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Early diagnosis and treatment with antifungal therapy can improve the prognosis of T. marneffei infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Talaromyces marneffei (Penicillium marneffei), first discovered in 1956, is a thermally dimorphic fungus that can cause severe infections in epidemic regions of Southeast Asia, particularly in immunocompromised patients [1,2,3]. It develops into a mycelium at 25 °C and into yeast at 37 °C, but only the yeast-like form has pathogenic potential. Patients with HIV/AIDS have been reported to be vulnerable to T. marneffei [4, 5]. However, a growing number of T. marneffei-infected patients without HIV have been reported in recent years [6,7,8]. Among non-HIV-infected patients, to our knowledge, those who suffer from long-standing pulmonary sarcoidosis have rarely been reported to be subject to T. marneffei infection. We herein describe the details of the first such case worldwide.

Case presentation

A 41-year-old man, a native of Cangnan County in the Zhejiang province of southeast China, was admitted to our hospital because of a 3-week history of daily hyperpyrexia and sputum-coughing in April 2017. The first time that multiple pulmonary nodules and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy were found in chest CT (Fig. 1a) was 7 years ago. The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary sarcoidosis according to the results of a transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) and transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), which revealed lymphocytes, columnar epithelial cells and a cloud of epithelial-like cells. In the following years, he received follow-up chest CT examination and corticosteroid treatment irregularly. The patient met the ATS/WASOG diagnostic criteria for sarcoidosis because there was no progression of the lesions in recent years. With the pre-existing pulmonary sarcoidosis, he had been diagnosed with the progression of pulmonary sarcoidosis in a certain hospital in Shanghai 12 days prior. At that time, he was examined with chest CT and central ultrasound bronchoscopy. The chest CT showed space-occupying lesions of the right superior lobe, probably a malignant tumour, mediastinal and right hilum lymphadenopathy, and plaques and nodules disseminated throughout the bilateral lung, probably pneumoconiosis and metastasis (MT) (Fig. 1b). Compared to the initial chest CT performed in 2015 (Fig. 1a), Fig. 1b shows increased miliary pulmonary nodules and a new pulmonary consolidation. Central ultrasound bronchoscopy revealed that a nodular projection was on the surface of both superior lobar bronchus and that stenosis appeared in the right superior lobar bronchus, especially the right apical segment (Fig. 2a). The patient received transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) 6 times when the ultrasound probed a tumour outside of the right primary bronchus and lymphadenectasis in 11R and 10 L. The pathology exam found fibrous tissue hyperplasia accompanied by apparent infiltration of monocytes and lymphocytes. There was no evidence of non-caseating epithelioid granuloma. Moreover, eosinophils were infiltrated in some areas. After 3 days of prednisone and levofloxacin, the fever and cough persisted, and there was no clinical improvement; even worse, skin lesions (Fig. 3a) erupted on his back.

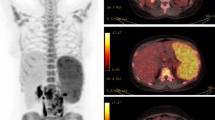

a Past chest CT scan (February 20, 2015) showing bilateral lung diffuse miliary nodules. b Chest CT scan on day 10 before hospital admission (March 31, 2017) showing plaques and nodules disseminated throughout the bilateral lung. c Chest CT scan on day 2 of hospital admission (April 12, 2017) showing bilateral lung diffuse miliary nodules, multiple patchy exudative shadows in the bilateral superior lobes and right inferior lobes, and an air bronchogram in the consolidation of the right superior lobe. d Chest CT scan during follow-up (July 18, 2017) showing the absorption of lesions and nodules

The patient was pale and had intermittent high fever on the day of admission to our hospital. Born and raised in Cangnan, he denied a residential history in any epidemic regions. After his admission, imipenem cilastatin was promptly used against the infection. Immediate HRCT revealed bilateral lung diffuse miliary nodules, multiple patchy exudative shadows in the bilateral superior lobes and right inferior lobes, air bronchogram in the consolidation of the right superior lobe, multiple hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathies and local pleural thickening (Fig. 1c). The image did not change much compared to the previous one. The results of the following laboratory routine examinations are shown in Table 1. Microbiology analysis showed that repeated sputum smears, sputum culture, and blood cultures were negative. Combining these clinical manifestations and biochemical analyses, the chance of tuberculosis diagnosis could not be excluded. However, the T-spot was negative, and acid-fast bacilli were not present. It was difficult to explain the extremely elevated IgE and eosinophils in the blood as well as the eosinophil infiltration in the bronchus on the monism of tuberculosis. After providing informed consent, the patient underwent bronchoscopy again, which revealed an unevenness of the trachea in the subglottic region as well as protrusions on the tracheal wall, especially in the right superior lobar bronchus (Fig. 2b). A subsequent (1/3) -b-D-glucan (G) assay was positive, and a smear was positive for fungus in the BAL. All the evidence above was associated with a higher likelihood of fungal infection. Along with the evidence that there was no clinical improvement after 4 days of antibacterial therapy, the patient was suspected of pulmonary aspergillosis because it was endemic in the region of Cangnan. He was immediately treated with voriconazole at a dosage of 200 mg/dL every 12 h via intravenous administration starting on April 14, 2017. Ultimately, the fungal culture of bronchoalveolar confirmed the diagnosis of T. marneffei infection on April 20 (Fig. 3b). His fever returned to normal, and his respiratory signs disappeared gradually after an 8-day treatment, as well as his skin lesions. The results of the chest CT re-examination showed that the lung lesions were markedly absorbed after 3 months (Fig. 1d). He continued to receive follow-up antifungal treatment.

Discussion

Talaromyces marneffei, the only known dimorphic fungus of the genus Penicillium, was first isolated in 1956 in Vietnam from the bamboo rat Rhizomys sinensis [9]. A diagnostic characteristic of T. marneffei is mould-to-yeast conversion or phase transition, which is thermally regulated. Since the first natural T. marneffei infection was reported in 1973 [10], it has been increasingly observed both in AIDS patients and in HIV-negative individuals in recent years. Among non-HIV-infected individuals, pulmonary T. marneffei infection has been reported in patients with a history of pulmonary tuberculosis [6] or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [11]. However, to our knowledge, the infection has not been reported in patients with a history of pulmonary sarcoidosis. In this article, we first present such a case of a confirmed diagnosis of T. marneffei infection in a non-HIV-infected patient with pre-existing pulmonary sarcoidosis.

The main route of transmission of T. marneffei is inhaling the infectious agent; rarely is there direct animal contact. The typical clinical manifestations are fever, weight loss, skin lesions, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and respiratory signs, but the severity of the disease depends on the patient’s immune status [12, 13]. The patient in this case was a non-HIV-infected patient and was young, but his lung immunity was probably impaired due to long-standing pulmonary sarcoidosis. Early in 1988, Deng, Z. et al. [14] reported that southern China was one of the endemic regions for T. marneffei. Specifically, these clinical features, as indicated by hyperpyrexia, sputum-coughing, persistent elevated IgE and eosinophils in the blood, eosinophil infiltration in the bronchus, positive BAL-G assay (G assay of BAL), and T-spot negativity as well as the failure to reveal acid-fast bacilli, led to possible infection with a pulmonary fungus. As the accuracy of the BAL-G assay is marginal rather than absolutely specific for invasive fungal disease (IFDs), the results should not be interpreted alone but should be used as a part of a full assessment together with clinical features, image findings and other laboratory results for the diagnosis of IFDs [15]. Finally, the T. marneffei infection was confirmed with bronchoalveolar lavage culture. In addition to the BAL, commonly used clinical specimens in the literature include bone marrow aspirate, blood, lymph node biopsies, skin biopsies, skin scrapings, sputum, pleural fluid, liver biopsies, cerebrospinal fluid, pharyngeal ulcer scrapings, palatal papule scrapings, urine, stool samples, and kidney, pericardium, stomach or intestine specimens [16]. Different from previously reported cases of pulmonary T. marneffei infection in non-HIV-infected patients, the pre-existing pulmonary sarcoidosis covered up the clinical futures of T. marneffei and easily misled us about the progression of the original disease or lymphoma.

The T. marneffei presentation upon chest CT is non-specific, as displayed by multiple patchy exudative shadows, pulmonary consolidation, nodular shadows, a ground-glass appearance, miliary lesions, and nodular masses, commonly accompanied by mediastinal and hilum lymphadenopathy and sometimes by cavitary lesions [17]. Compared to the chest CT (Fig. 1a) 2 yrs prior, the chest CT (Fig. 1b and c) showed the progression of pulmonary nodules and the new consolidation lesions. In this respect, we would be more likely to suspect the progression of pulmonary sarcoidosis and to ignore the possibility of fungal infection. The chest CT (Fig. 1d) re-examined after anti-fungal treatment for 3 months showed that the lung lesions as well as some pulmonary nodules were markedly absorbed. However, the mediastinal lymphadenopathy did not improve in all the groups, as shown in Fig. 1. There was a strong likelihood that the lymphadenopathy was due to long-standing pulmonary sarcoidosis.

The non-specific presentation of T. marneffei highlights the importance of the rapid diagnosis and treatment of this potentially life-threatening mycosis. T. marneffei is susceptible to itraconazole and amphotericin B in vitro [18, 19]. A study from China revealed that voriconazole had the lowest MIC (ranged from 0.004 mg/L to 0.25 mg/L) in comparison to other antifungal agents, and the results showed that voriconazole and itraconazole are active against T. marneffei isolated in vitro [20]. However, a documented study reported that a single dose of itraconazole for the treatment of T. marneffei infection in HIV-infected patients was non-effective [21]. A retrospective study evaluating the efficacy and safety of voriconazole to treat patients with T. marneffei infection suggested that voriconazole was an effective, well-tolerated therapeutic option for this disease [22]. Taken together, we preferred voriconazole as the antifungal drug for this case. Indeed, the patient recovered rapidly, and the lung lesions were markedly absorbed after treatment.

Conclusions

In summary, our study reports a case of T. marneffei infection in a non-HIV-infected patient with a history of pulmonary sarcoidosis in an endemic fungal area. This study invites clinicians to consider T. marneffei infection in non-HIV-infected patients with underlying diseases because early diagnosis and proper treatment lead to a reduction in the mortality associated with T. marneffei.

Abbreviations

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- G assay:

-

(1/3) -b-D-glucan assay

- GM assay:

-

Galactomannan antigen assay

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution computed tomography

- T. marneffei :

-

Talaromyces marneffei

- TBNA:

-

Transbranchial needle aspiration

References

Capponi M, Segretain G, Sureau P. Penicillosis from Rhizomys sinensis. Bulletin de la Societe de pathologie exotique et de ses filiales. 1956;49(3):418–21.

Xiang Y, Guo W, Liang K. An unusual appearing skin lesion from Penicillium marneffei infection in an AIDS patient in Central China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(1):3.

Hee CH, Pil CY, Cho KJ. Penicillium marneffei infection in a HIV-positive patient: a comparison of bronchial washing cytology and biopsy. J Cytol. 2017;34(1):45–8.

Wang YF, Xu HF, Han ZG, Zeng L, Liang CY, Chen XJ, Chen YJ, Cai JP, Hao W, Chan JF, et al. Serological surveillance for Penicillium marneffei infection in HIV-infected patients during 2004-2011 in Guangzhou, China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(5):484–9.

Wong SY, Wong KF. Penicillium marneffei infection in AIDS. Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:764293.

Wang PH, Wang HC, Liao CH. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei mimicking paradoxical response and relapse in a non-HIV patient with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2015;78(4):258–60.

Liu GN, Huang JS, Zhong XN, Zhang JQ, Zou ZX, Yang ML, Deng JM, Bai J, Li MH, Mao CZ, et al. Penicillium marneffei infection within an osteolytic lesion in an HIV-negative patient. Int J Infectious Dis. 2014;23:1–3.

Qiu Y, Zhang J, Liu G, Zhong X, Deng J, He Z, Jing B. A case of Penicillium marneffei infection involving the main tracheal structure. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:242.

Segretain G. Penicillium marneffei n.Sp., agent of a mycosis of the reticuloendothelial system. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1959;11:327–53.

DiSalvo AF, Fickling AM, Ajello L. Infection caused by Penicillium marneffei: description of first natural infection in man. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973;60(2):259–63.

De Monte A, Risso K, Normand AC, Boyer G, L'Ollivier C, Marty P, Gari-Toussaint M. Chronic pulmonary penicilliosis due to Penicillium marneffei: late presentation in a french traveler. J Travel Med. 2014;21(4):292–4.

Vanittanakom N, Cooper CR Jr, Fisher MC, Sirisanthana T. Penicillium marneffei infection and recent advances in the epidemiology and molecular biology aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(1):95–110.

Hu Y, Zhang J, Li X, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Ma J, Xi L. Penicillium marneffei infection: an emerging disease in mainland China. Mycopathologia. 2013;175(1–2):57–67.

Deng Z, Ribas JL, Gibson DW, Connor DH. Infections caused by Penicillium marneffei in China and Southeast Asia: review of eighteen published cases and report of four more Chinese cases. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(3):640–52.

Shi XY, Liu Y, Gu XM, Hao SY, Wang YH, Yan D, Jiang SJ. Diagnostic value of (1 --> 3)-beta-D-glucan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for invasive fungal disease: a meta-analysis. Respir Med. 2016;117:48–53.

Supparatpinyo K, Khamwan C, Baosoung V, Nelson KE, Sirisanthana T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in Southeast Asia. Lancet. 1994;344(8915):110–3.

Zhou F, Bi X, Zou X, Xu Z, Zhang T. Retrospective analysis of 15 cases of Penicilliosis marneffei in a southern China hospital. Mycopathologia. 2014;177(5–6):271–9.

Cao C, Liu W, Li R, Wan Z, Qiao J. In vitro interactions of micafungin with amphotericin B, itraconazole or fluconazole against the pathogenic phase of Penicillium marneffei. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(2):340–2.

Sirisanthana T, Supparatpinyo K, Perriens J, Nelson KE. Amphotericin B and itraconazole for treatment of disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1998;26(5):1107–10.

Liu D, Liang L, Chen J. In vitro antifungal drug susceptibilities of Penicillium marneffei from China. J Infec Chemother : official journal of the Japan Society of Chemotherapy. 2013;19(4):776–8.

Su Q, Ying G, Liang H, Ye L, Jiang J, Liang B, Huang J. Single use of Itraconazole has no effect on treatment for Penicillium Marneffei with HIV infection. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18(7):441–5.

Ouyang Y, Cai S, Liang H, Cao C. Administration of Voriconazole in disseminated Talaromyces (Penicillium) Marneffei infection: a retrospective study. Mycopathologia. 2017;182(5–6):569–75.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All the data are fully available without restriction.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ and XMY conceived the study and developed the search strategy. XMY conducted the review of relevant articles and produced the draft of the manuscript. KJM and YLC contributed to the diagnosis and treatment. CSZ participated in data collection and interpretation. MYC and HC contributed to the literature review and drafted the table and figures. XYH and YFC edited the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of his clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., Miao, K., Zhou, C. et al. T. marneffei infection complications in an HIV-negative patient with pre-existing pulmonary sarcoidosis: a rare case report. BMC Infect Dis 18, 390 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3290-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3290-7