Abstract

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) contact tracing is a key strategy for containing TB and provides addition to the passive case finding approach. However, this practice has not been implemented in Tanzania, where there is unacceptably high treatment gap of 62.1% between cases estimated and cases detected. Therefore calls for more aggressive case finding for TB to close this gap. We aimed to determine the magnitude and predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB index cases in the city of Mwanza, Tanzania.

Methods

This study was carried out from August to December 2016 in Mwanza city at the TB outpatient clinics of Tertiary Hospital of the Bugando Medical Centre, Sekou-Toure Regional Hospital, and Nyamagana District Hospital. Bacteriologically-confirmed TB index cases diagnosed between May and July 2016 were identified from the laboratory registers book. Contacts were traced by home visits by study TB nurses, and data were collected using a standardized TB screening questionnaire. To detect the bacterioriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB, two sputum samples per household contact were collected under supervision for all household contacts following standard operating procedures. Samples were transported to the Bugando Medical Centre TB laboratory for investigation for TB using fluorescent smear microscopy, GeneXpert MTB/RIF and Löwenstein–Jensen (LJ) culture. Logistic regression was used to determine predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts.

Results

During the study period, 456 household contacts from 93 TB index cases were identified. Among these 456 household contacts, 13 (2.9%) were GeneXpert MTB/RIF positive, 18 (3.9%) were MTB-culture positive and four (0.9%) were AFB-smear positive. Overall, 29 (6.4%) of contacts had bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB. Predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts were7being married (Odds ratio [OR], 3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4–8.0; p = 0.012) and consuming less than three meals a day (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7; p = 0.009).

Conclusions

Our data suggest that in Mwanza, Tanzania, seven in 100 contacts living in the same house with a TB patient develop bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB. These results therefore underscore the need to implement routine TB contact tracing to control tuberculosis in high TB burden countries such as Tanzania.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is a deadly disease primarily transmitted through airborne droplets, particularly in populations that share air with infected individuals [1]. In TB high-burden countries, the majority of cases are diagnosed when patients seek health care at health-care facilities (“passive case finding”) [2, 3]. Active screening of individuals in contact with TB-infected cases is a key component in containing the disease in low-incidence countries. However, this practice has not been implemented in most high-burden countries [4].

The 2016 World Health Organization report on TB ranked Tanzania among the 22 countries with the highest tuberculosis burden worldwide [5]. To control TB, healthcare systems will need to detect more cases of TB at an earlier stage of the illness [6]. However, in 2016 WHO estimates high number of cases not reported and treated in high burden countries [5]. In Tanzania, WHO estimates 164,000 people had TB disease, of these, only 62,180 (37.9%) cases were notified [5]. This demonstrates a huge treatment gap of 62.1% of all people with TB in Tanzania were not reported and treated in Tanzania. This treatment gap is unacceptably high and calls for more aggressive case finding for TB (household contacts via active case findings) to close this gap. Active case finding by TB contacts tracing provides a promising addition to the passive case finding approach [7], as it a very effective method of increasing case detection rates [8]. However, this practice has not been implemented in Tanzania. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 41 studies showed that screening household contacts in middle- and low-income countries increased new case findings by 4.5% [1]. It is imperative to prioritize active case finding, as it leads to early diagnosis and shortens exposure of cases within the community [9,10,11].

Analysis of studies has indicated that, where the national prevalence of TB reaches 100 cases per 100,000 people, the active case-finding technique detected one case among 100 tested individuals [12]. Two studies in Tanzania showed having less education and living far from testing facilities to be factors associated with delayed case detection [13, 14]. Studies in three countries in West Africa have shown that the host and environmental factors, predicting pulmonary TB were male sex, HIV infection, smoking, history of asthma, family history of TB, marital status, adult crowding, and renting the house [15]. Studies outside Africa have shown the predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts include: male sex, low body weight, alcoholism, glucocorticoid therapy, and diabetes [16].

The WHO strongly recommends the practice of systematic screening of active TB household contact, people living with HIV, mining communities, workers exposed to silica, and imprisoned people. This practice is encouraged in general communities where prevalence is ≥100 per 100,000 people [17]. Active case finding is important in diagnosing new TB cases, which offers the opportunity to treat infected patients at an earlier stage, before signs and symptoms develop, especially in HIV endemic areas as HIV fuels TB transmission [18].

Therefore, this study aimed to determine bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB index cases in the city of Mwanza, Tanzania. It also determined predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts. A systemic review and meta-analysis of 41 studies showed that screening household contacts increased new case findings by 4.5% [1]. Therefore, we hypothesized that there is ≥5% of new bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB cases among these index cases in the city of Mwanza.

Methods

From August to December 2016, a retrospective study was done on newly bacteriologically confirmed TB index cases between May and July 2016 at TB outpatient clinics at Bugando Medical Centre (BMC) Tertiary Hospital, Sekou-Toure Regional Hospital, and Nyamagana District Hospital in the city of Mwanza. A retrospective chart review from the laboratory registers book was done to identify new bacteriologically confirmed TB index cases. These index cases received home visits by the study TB nurses and household contacts were screened for TB using a standardized TB screening questionnaire.

Demographic information and address and phone numbers of the index cases were extracted from registry books. Before visits, a call was made to the index case to inform of the visit, arrange the day and suitable time, and discuss the possibility of meeting all house inhabitants. Calls were made using the telephone number extracted from the TB laboratory registers. The study team visited all cases who accepted.

Index case household contacts who were willing to participate were asked to sign giving their consent, and were requested to provide a spot sputum sample regardless of TB signs or symptoms. Those who provided a sample were left with a sputum container for depositing the morning specimen.

Special arrangements were made to accommodate contacts that were unavailable during the first visit. We optimized our effort to collect sputum samples from children by instructing and supervising them in producing sputum. Contacts with clinical signs, especially children who were unable to produce sputum, were referred to the nearby TB clinic and managed in accordance with the national TB guidelines.

The household contacts who were able to produce the sputum sample were enrolled into this study while those who were not able to produce sputum were excluded. The study did not collect and report data on those excluded based on refusal of participation, could not be reached, or could not produce sputum. At the time of home visits, the study TB nurses administered questionnaires to only those who provided spot sputum samples, to obtain the socio-demographic, baseline information, and predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB. The predictors investigated were symptoms of pulmonary TB (cough, fever, weight loss, excessive night sweats and hemoptysis), current smoking, house size, distance to health facility, number of people living in the house and number of meals taken per day. Later, the house parameters were measured using a tape measure.

Study definitions

Bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB was defined as the individual having at least one positive result from AFB smear, GeneXpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) or LJ culture. We used a definition of a household contact as defined elsewhere but with a stringent criteria on time. In this context a household contact was defined as a person who had been in close and frequent contact by living in the same house with a TB index case for at least 3 days in between 3 weeks before diagnosis and 1 week after diagnosis and commencement of treatment [19].

Sample collection and laboratory analysis

Contacts were instructed and supervised to collect one spot sample and one morning sputum sample generated from a deep cough. The samples were analyzed by GeneXpert MTB/RIF. In cases where this was not sufficient, the second sample was used. Additionally, two culture slopes and two smears were made from each sample. We performed all three tests (GeneXpert MTB/RIF, LJ culture and fluorescent smear microscopy) for all 456 contacts at BMC TB laboratory. Routine laboratory standard operating procedures were used to analyze the samples. Bacterial culture was performed using Löwenstein–Jensen (LJ) medium base. All standard operating procedures were validated using known samples and the validation reports were documented for traceability. Staff who analyzed samples were trained and assessed for competency to ensure procedures were properly followed. Equipment for analyzing samples was validated and maintained in accordance with the respective manufacturer’s instructions. TB control strains were cultured against samples to control the culturing process.

Data management and statistical analysis

Laboratory personnel collected laboratory data, while a TB nurse collected clinical data about the symptoms for TB. All data generated from home visit and laboratory work were first collected in hard copy, except for GeneXpert MTB/RIF results, which were generated by the machine. Data were then double entered into Epi Data version 3.1 (The Epi Data Association, Odense, Denmark). Accessing of data was limited to authorized personnel and amendment of records was not allowed. The researcher maintained all participants’ data in a securely locked cupboard. Information on participants’ positive TB diagnoses was forwarded to the TB coordinator to assist with patient treatment.

Data were then imported into STATA 13 (Stata Corp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for management and analysis. We reported the median with interquartile range (IQR) for continuous data and simple frequencies (numbers), and percentages (proportions) for categorical data. The main outcome was bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB detected by contact tracing. The factors assessed were household contact’s relationship with the TB index cases, TB symptoms, level of education, house size, smoking, age, sex, marital status, number of meals per day, number of family members, and distance to the nearest health center. We employed univariate followed by multivariate logistic regression models to determine factors associated with bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among contacts. Multivariate logistic regression was conducted on factors that were statistically significant in univariate regression. Odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was computed.

Informed consent and ethical clearance

Study participants’ consent was obtained after identification of TB-positive cases from a laboratory register in Mwanza. The participants were given clear explanation about the project and how they would participate, as well as the benefits. A consent form was signed upon agreement to participate. Consent forms were translated in the Swahili National language. For participants who were unable to read, their consent were witnessed by explaining the purpose of the study and its benefits. The study team clearly explained that participation into the study was absolutely voluntary and participants were allowed to leave the study at any time. For children below 18 years, informed consent was sought from parents or guardians as per Tanzania medical research regulations.

The study was approved by the ethics committees of both the Joint Catholic University of Health and Allied Science/Bugando Medical Centre (Mwanza, Tanzania) and Stellenbosch University (Cape Town, South Africa).

Referral of contacts with bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB

Identified TB-positive contacts from any of our testing methods were referred to the nearby TB clinic receive free TB treatment. Contacts especially children who were not able to produce sputum but had presented with signs and symptoms of TB were referred to nearby TB clinic for further investigations.

Results

Description of participant characteristics

Between May and July, a total of 93 TB index cases were identified from laboratory registers. Upon following of these cases, 456 household contacts met eligibility criteria and were enrolled into the study. The median age for the household contacts was 22 (IQR, 15–37) years. A slight majority of participants were female 57.0% (260/456), and 55.5% (253/456) were married. The most common contact relationships with cases were siblings at 41% (187/456), followed by parents at 24.6% (112/456). More than half of the contacts, 59.2% (270/456), reported they had three or more meals a day. There were 4.4% (20/456) household contacts who were habitual smokers (Table 1).

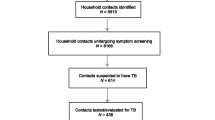

Among the 456 household contacts, 13 (2.9%) were positive for GeneXpert MTB/RIF, 18 (3.9%) were M.tb-culture positive and and four (0.9%) were AFB-smear positive. Four were positive for all three tests. Six were only positive for both GeneXpert MTB/RIF and culture. Seven contacts only GeneXpert MTB/RIF positive, whereas 12 were only positive for the culture. None were positive for only the smear, smear and culture, and smear and GeneXpert MTB/RIF. There were 10 (2.1%) samples that had invalid results on GeneXpert MTB/RIF and 16 (3.5%) contaminated in the culture. Overall, 29 (6.4%) were bacteriologically diagnosed TB cases (Fig. 1).

Predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts

Following multivariate logistic regression analysis, the independent predictors of bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB among household contacts were: being married (OR, 3.3; 95% CI, 1.4–8.0; p = 0.012) and consuming less than three meals a day (OR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7; p = 0.009). (Table 2).

Discussion

Using active case finding among household contacts of bacteriologically-confirmed adult pulmonary TB cases, we found that 6.4% of household contacts who produced a sputum sample also had bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB in Mwanza, Tanzania. These results mean the active case-finding technique provides an increased TB detection rate about 20 times higher than the 306 per 100,000 people detection rate achieved by passive diagnosis [5].

Our results provided a high yield compared with Uganda, which was 3.5% [9], and 4.5% from a systematic review involving 41 case-finding studies that was conducted to synthesize evidence of implementing active case finding as an effective approach for raising the TB-detection rate [1]. The results from the present study were consistent with active case findings in urban slums in southeastern Nigeria, which reported 6.4% of TB cases undiagnosed [20]. Our results therefore reinforce the WHO recommendation to implement TB case-finding targeting areas at high risk of TB (e.g., mines and prisons).

Our results found a statistically significant association between bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB and taking less than three per day. This could be explained by the fact that people with good nutrition had improved immunity [21, 22]. Nutrition plays a major role in the management of both acute and chronic diseases, in terms of body’s response to the pathogenic organism [21,22,23]. An array of nutrients like macro- and micro-nutrients (vitamins, minerals, and trace elements) are associated with boosting the host’s immune responses against intracellular pathogens including Mycobacterium tuberculosis [23]. These nutrients have an immuno-modulatory effects in controlling the infection and inflammation process. Hence nutritional deficiency of any form may greatly increases an individual’s susceptibility to progression of infection to disease [23].

The majority of contacts with bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB were married. This high proportion may be due to the fact that married people share a bedroom with their spouses, and are in closer contact with other people as well such as their children, friends, etc. than a single person. Thus, perhaps that closer contact to spouse, and to children, friends, etc., predisposes them to an infectious contact than any other person in the house [24].

We anticipated the number of people staying in houses per square meter of floor space (crowding), relationship of contacts with TB cases, and education level could be associated with TB among household contacts. Our results on risk factors differed from in a multicenter study done in West Africa that looked at risk factors for TB; that study found an association between adult crowding and renting of houses [15]. Our results show no statistically significant association between the mentioned factors.

The limitations to this study were we did not follow up house-hold contacts for some times and did not induce sputum to those unable to produce it especially children and also did not diagnose clinical pulmonary tuberculosis and extra-pulmonary TB. If these could be done the yield of active case finding could be higher. There could the possibility of bias in contact tracing and confounding, and the therefore the sample size could not be the representative for the city of Mwanza. Examining HIV was outside the scope of this study, but remains critically important for any intervention targeting TB.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that seven in 100 TB household contacts had bacteriologically-confirmed pulmonary TB. This figure underscores the need for implementation of routine contact tracing to control TB in developing countries. Further studies with follow up component are warranted on clinical tuberculosis, sputum induction, especially on children and those who can not produce sputum. Furthermore, based on this association, programs targeting diet should be integrated into TB services.

Abbreviations

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- LJ:

-

Löwenstein–Jensen

- MTB/RIF:

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis/Rifampicin

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Morrison J, Pai M, Hopewell PC. Tuberculosis and latent tuberculosis infection in close contacts of people with pulmonary tuberculosis in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(6):359–68.

Fox GJ, Dobler CC, Marks GB. Active case finding in contacts of people with tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

Senkoro M, Hinderaker S, Mfinanga S, Range N, Kamara D, Egwaga S, van Leth F. Health care-seeking behaviour among people with cough in Tanzania: findings from a tuberculosis prevalence survey. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(6):640–6.

Ntinginya E, Squire S, Millington K, Mtafya B, Saathoff E, Heinrich N, Rojas-Ponce G, Kowuor D, Maboko L, Reither K. Performance of the Xpert® MTB/RIF assay in an active case-finding strategy: a pilot study from Tanzania [short communication]. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(11):1468–70.

World Health Organization: Global tuberculosis report. 2016. Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children: First National Tuberculosis Prevalence Survey in the United Republic of Tanzania-Final report 2015, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania http://ihi.eprints.org/3361/1/PST_final_report_Sept_2013.pdf Accessed 11 Jan 2017.

Begun M, Newall AT, Marks GB, Wood JG. Contact tracing of tuberculosis: a systematic review of transmission Modelling studies. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e72470. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072470.

Behr MA, Hopewell PC, Paz EA, Kawamura LM, Schecter GF, et al. Predictive value of contact investigation for identifying recent transmission of mycobacterium tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:465–9.

Sekandi J, Neuhauser D, Smyth K, Whalen C. Active case finding of undetected tuberculosis among chronic coughers in a slum setting in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13(4):508–13.

van't Hoog AH, Laserson KF, Githui WA, Meme HK, Agaya JA, Odeny LO, Muchiri BG, Marston BJ, DeCock KM, Borgdorff MW. High prevalence of pulmonary tuberculosis and inadequate case finding in rural western Kenya. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(9):1245–53.

Wood R, Middelkoop K, Myer L, Grant AD, Whitelaw A, Lawn SD, Kaplan G, Huebner R, McIntyre J, Bekker L-G. Undiagnosed tuberculosis in a community with high HIV prevalence: implications for tuberculosis control. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(1):87–93.

Kranzer K, Houben RM, Glynn JR, Bekker L-G, Wood R, Lawn SD. Yield of HIV-associated tuberculosis during intensified case finding in resource-limited settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(2):93–102.

Wandwalo E, Mørkve O. Delay in tuberculosis case-finding and treatment in Mwanza, Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(2):133–8.

Ngadaya ES, Mfinanga GS, Wandwalo ER, Morkve O. Delay in tuberculosis case detection in Pwani region, Tanzania. A cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9(1):196.

Lienhardt C, Fielding K, Sillah J, Bah B, Gustafson P, Warndorff D, Palayew M, Lisse I, Donkor S, Diallo S. Investigation of the risk factors for tuberculosis: a case–control study in three countries in West Africa. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):914–23.

Herzmann C, Sotgiu G, Bellinger O, Diel R, Gerdes S, Goetsch U, Heykes-Uden H, Schaberg T, Lange C; TB or not TB consortium. Risk for latent and active tuberculosis in Germany. Infection 2017;45(3):283–290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-016-0963-2. Epub 2016 Nov 19. PMID: 27866367.

World Health Organization: Systematic screening for active tuberculosis: principles and recommendations: 2013. Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/tb/tbscreening/en/ Accessed 18 Jan 2017.

World Health Organization: Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case-finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. 2011. Geneva, Switzerland whqlibdocwhoint/publications/2011/9789241500708_engpdf Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Stop TB Partnership Childhood TB Subgroup World Health Organization. Guidance for National Tuberculosis Programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. Chapter 1: introduction and diagnosis of tuberculosis in children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2006;10 (10):1091–1097. PMID: 17044200.

Ogbudebe CL, Chukwu JN, Nwafor CC, Meka AO, Ekeke N, Madichie NO, Anyim MC, Osakwe C, Onyeonoro U, Ukwaja KN. Reaching the underserved: active tuberculosis case finding in urban slums in southeastern Nigeria. Int J Mycobacteriology. 2015;4(1):18–24.

Bhargava A. Undernutrition, nutritionally acquired immunodeficiency, and tuberculosis control. BMJ 2016;355:i5407. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5407. PMID:27733343.

Grobler L, Nagpal S, Sudarsanam TD, Sinclair D. Nutritional supplements for people being treated for active tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;(6):CD006086. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006086.pub4. Review. PMID: 27355911.

Chandrasekaran P, Saravanan N, Bethunaickan R, Tripathy S. Malnutrition: Modulator of immune responses in tuberculosis. Front Immunol 2017;8:1316. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01316. eCollection 2017. Review.PMID:29093710.

Hudelson P. Gender differentials in tuberculosis: the role of socio-economic and cultural factors. Tuber Lung Dis. 1996;77(5):391–400.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support provided by the members the tuberculosis laboratories of Bugando Medical Centre, Sekou-Toure Regional Hospital and Nyamagana District Hospital.

Funding

This study was funded by Medical Mission Institute, Wuerzburg, Germany as the part of sponsorship for Masters of Sciencedegree in Clinical Epidemiology awarded by Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials can be obtained on request from the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study: MB EO SEM CK. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: MB BRK CK. Collected the data: MB BRK. Analyzed the data: MB BRK SEM. Wrote the manuscript: MB. Edited and reviewed critically the manuscript: MB BRK LGA EO SEM CK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study participants were clearly informed on the aims and benefits of the study as well as the procedures involved before being enrolled into the study. Written informed consent was obtained before sample collection for adults and for children, their parents or guardian signed the written consent form on their behalf. The study was approved by the Joint Bugando Medical Centre and Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences Ethical Committee in Mwanza, Tanzania as well as approved by the Ethical Committee Stellenbosch University in Capetown, South Africa.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare that we have no competing interest to report.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Beyanga, M., Kidenya, B.R., Gerwing-Adima, L. et al. Investigation of household contacts of pulmonary tuberculosis patients increases case detection in Mwanza City, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 18, 110 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3036-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3036-6