Abstract

Background

Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) infection is characterised by the persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Expanding HBV diagnosis and treatment programmes into low resource settings will require high quality but inexpensive rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) in addition to laboratory-based enzyme immunoassays (EIAs) to detect HBsAg. The purpose of this review is to assess the clinical accuracy of available diagnostic tests to detect HBsAg to inform recommendations on testing strategies in 2017 WHO hepatitis testing guidelines.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using 9 databases. Two reviewers independently extracted data according to a pre-specified plan and evaluated study quality. Meta-analysis was performed. HBsAg diagnostic accuracy of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) was compared to enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and nucleic-acid test (NAT) reference standards. Subanalyses were performed to determine accuracy among brands, HIV-status and specimen type.

Results

Of the 40 studies that met the inclusion criteria, 33 compared RDTs and/or EIAs against EIAs and 7 against NATs as reference standards. Thirty studies assessed diagnostic accuracy of 33 brands of RDTs in 23,716 individuals from 23 countries using EIA as the reference standard. The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 90.0% (95% CI: 89.1, 90.8) and 99.5% (95% CI: 99.4, 99.5) respectively, but accuracy varied widely among brands. Accuracy did not differ significantly whether serum, plasma, venous or capillary whole blood was used. Pooled sensitivity of RDTs in 5 studies of HIV-positive persons was lower at 72.3% (95% CI: 67.9, 76.4) compared to that in HIV-negative persons, but specificity remained high. Five studies evaluated 8 EIAs against a chemiluminescence immunoassay reference standard with a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 88.9% (95% CI: 87.0, 90.6) and 98.4% (95% CI: 97.8, 98.8), respectively. Accuracy of both RDTs and EIAs using a NAT reference were generally lower, especially amongst HIV-positive cohorts.

Conclusions

HBsAg RDTs have good sensitivity and excellent specificity compared to laboratory immunoassays as a reference standard. Sensitivity of HBsAg RDTs may be lower in HIV infected individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An estimated 257 million individuals worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), of whom 2.7 million are co-infected with HIV [1]. Globally, between 20 and 30% of patients with chronic HBV infection will develop cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma [2], accounting for the majority of the attributable 686, 000 deaths [3] and 21 million disability-adjusted life-years annually [4]. Most individuals with chronic HBV infection however are not aware of their serostatus. Delayed diagnosis means that many may progress to long term complications and present only with advanced disease [5]. Expanded access to testing for HBV is critically important in order to increase numbers of infected individuals aware of their status for linkage to care, as well as identifying candidates for HBV vaccination and facilitating prevention and control efforts.

In March 2015 the World Health Organization (WHO) published the first global guidelines for the prevention, care, and treatment of individuals with chronic HBV infection [5]. These guidelines focused on assessment for treatment eligibility, initiation of first and second-line therapies, and monitoring. These initial guidelines did not include testing recommendations, and in particular which tests to use. Given the large burden of HBV in low and middle income settings where there are limited or no existing HBV testing guidelines, the development of HBV testing guidelines is a priority.

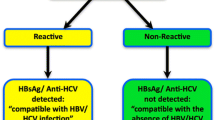

Advances in HBV detection technology have created new opportunities for testing, referral, and treatment. Chronic HBV infection is defined as persistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBSAg) for at least six months, and the testing strategy involves an initial serological test to detect HBsAg followed by nucleic-acid amplification test (NAT) for detection of HBV DNA viral load to help guide treatment decisions [5]. HBsAg can be detected using rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) in lateral flow, flow through or simple agglutination assays formats. Laboratory-based immunoassays to detect HBsAg include traditional radioimmunoassays (RIA) and enzyme immunoassays (EIA), as well as newer technologies such as electrochemiluminescence immunoassays (ECLIA), microparticle enzyme immunoassays (MEIA) and chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassays (CMIA), which use signal amplification to give quantitative measurements.

Previous systematic reviews on HBV infection have focused on effectiveness of immune responses to HBV vaccination [6], surveillance of cirrhosis [7], and evaluation of treatment effectiveness [8]. Prior reviews on hepatitis B testing [9,10,11] only focused on the performance of tests that can be used at the point of care. They also included evaluations with unclear reference standards and studies that used serum panels to evaluate test performance, which are inappropriate for assessing clinical or operational diagnostic accuracy in the field. This review aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of assays used to detect HBsAg in order to inform WHO and other guidelines on hepatitis testing [12]. This was the first study exclusively comparing the clinical performance of both RDTs and laboratory-based immunoassays, in addition to addressing the question of accuracy in the context of HIV status. The accuracy of HBsAg assays against a NAT reference standard was also undertaken, given the importance of reducing transmission during the seroconversion period and in the diagnosis of occult hepatitis B where HBsAg may not be detectable, which is more common with HIV co-infection. The purpose of this review was to provide quantitative evidence of the accuracy of available diagnostics to detect HBsAg in order to inform global guidelines.

Methods

Search strategy and identification of studies

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis on the diagnostic accuracy of HBsAg tests. The review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42015020313) and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) check list. We utilised standardised methods for systematic reviews on diagnostics, including an a priori protocol (Additional file 1).

Literature search strategies were developed by a medical librarian with expertise in systematic review searching, using a search algorithm consisting of terms for: hepatitis B, diagnostic tests, and diagnostic accuracy. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Science Citation Index Expanded, SCOPUS, Literatura Latino-Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS), WHO Global Index Medicus, WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry and the Web of Science. We also contacted researchers, experts and authors of major trials, with no relevant manuscripts in preparation identified. Additional pertinent citations were identified through bibliographies of retrieved studies.

Abstracts were screened by reviewers AA and HK according to standard inclusion and exclusion criteria. All studies identified for full manuscript review were assessed independently by two reviewers (AA and OV) against inclusion criteria. Papers were accepted or rejected, with reasons for exclusion specified. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between review authors and, when required, a third independent reviewer (RP).

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria were: case-control, cross-sectional, cohort studies or randomized trials published between 1996 and May 2015; primary purpose of evaluating HBsAg test accuracy; commercially available laboratory immunoassays or NAT as reference standard; any clinical specimen type. We excluded: articles in languages other than English; conference abstracts, comments or review papers; studies only reporting sensitivity or specificity without reference standards; studies using commercially prepared reference panels.

We included studies reporting original data from patient specimens in all age groups, settings, countries and specimen types. We performed a sub-analysis comparing test accuracy before 2005 with more recent studies published between 2005 and 2015 as the accuracy of reference standard immunoassays has improved over time. This time period was chosen as it was 10 years prior to the literature search, matched with a similar meta-analysis on hepatitis C tests (Ref Paper 11), and was around the time of the last WHO review of HbsAg assay operational characteristics [13]. Studies comparing the accuracy of laboratory based immunoassays were only included if they used CMIAs as the reference standard; most excluded studies using other platforms included reference panels, while five specifically used non-CMIA reference assays. Given the association between false negatives and a low OD/CO, it was reasonable to presume sensitivity is reduced with low HBsAg levels. CMIA has excellent analytical sensitivity (0.05 IU/ml) [14,15,16], and can be used to quantitate HBsAg levels in clinical specimens [17]. These platforms are the most widely used in clinical practice [18] given automation and high throughput, with data on kinetics and sensitivity in HIV-HBV co-infection.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (AA and OV) independently extracted data and reached agreement on the following variables: study author and year; study location and design; specimens tested; eligibility criteria; index test and reference standard, including manufacturer; raw cell numbers (true positives, false negatives, false positives, true negatives); HIV co-infection; sources of funding and reported conflict of interest.

Study quality was evaluated using the QUADAS-2 tool [19], which evaluates risk of bias (patient selection, index test, reference standard, and patient flow through) and applicability concerns (patient selection, index test, reference standard).

Data analysis and synthesis

We conducted meta-analysis pooling data using the DerSimonian-Laird bivariate random effects model (REM) to calculate pooled sensitivity and specificity with 95% confidence intervals (CI), which were used to estimate positive and negative likelihood ratios (PLR, NLR). Heterogeneity was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots and estimates of τ2 for diagnostic odds ratios (DOR) to measure between study variability. We performed sub-group analysis based on study year (2005–2015); tests brands (for brands that were evaluated in at least three studies); sample type and HIV status. All statistical analysis and figures were generated using Meta-Disc© version 1.4.7. (XI Cochrane Colloquium Barcelona, Spain).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

A total of 11,589 citations were identified, and 293 full-text articles examined which identified 40 studies meeting pre-defined criteria (Fig. 1). Of the included studies, 33 compared RDTs [14, 18, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] and/or EIAs [14, 47,48,49,50] against an immunoassay reference standard, of which five focused on accuracy in HIV-positive individuals [26, 44,45,46,47]. Seven studies compared RDTs [51,52,53] and/or EIAs [53,54,55,56,57] against a NAT reference standard, of which 3 had data from HIV-positive patients [53, 56, 57]. Studies were all either cross-sectional or case-control, predominantly in the laboratory setting, and performed in a broad range of populations, including healthy volunteers, blood donors, pregnant women, incarcerated adults, HIV and hepatitis patient cohorts with confirmed HBV infection. The prevalence of HBV ranged from 1.9 to 84% in populations tested. A mixture of serum, plasma and whole blood was used for RDTs, while studies of EIAs were performed on serum or plasma samples. Study characteristics are presented in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Assessment of the quality of the studies

The QUADAS-2 assessment for risk of bias of each study, including sub-studies deriving separate data points is presented in (Fig. 2a, b), with a summary in (Fig. 3). Bias in patient selection was generally attributable to a case-control study design (38%), or from enrolment of highly selected populations such as blood donors or those with known hepatitis B virus infection. Risk of bias from the index test was most commonly due to insufficient reporting of blinding or evaluation of RDTs which are no longer commercially available. Although the majority of studies did not specify the exact time interval between performance of the index and reference assays, it was assumed to be at low risk of bias as the assays were performed on the same sample. Applicability was judged to be higher risk for bias predominantly due to inclusion of older studies, those that evaluated tests which are no longer commercially available or studies using a NAT reference.

Diagnostic accuracy of rapid tests for HBsAg detection

Thirty studies [14, 18, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] assessed the accuracy of 33 different brands of RDTs in 23,716 individuals, which resulted in 63 data points for sensitivity and specificity. The reference standards used were CMIA in 5 studies, MEIA in 3 studies, and EIA/ELISA in 25 studies, with 3 studies using more than one type of reference assay. Test evaluations were conducted in 23 countries: six studies were conducted in high-income country studies [23, 27, 29, 32, 38, 42], two in upper-middle income country studies [14, 34], nine in lower-middle income [21, 24, 28, 30, 31, 33, 35, 39, 47], and six in low income [18, 20, 22, 40, 43, 46] countries, with income levels classified according to the World Bank ranking criteria. The overall pooled sensitivity and specificity were 90.0% (95% CI: 89.1, 90.8) and 99.5% (95% CI: 99.4, 99.5), respectively. The positive and negative likelihood ratios were 117.5 (95% CI: 67.7, 204.1) and 0.10 (95% CI 0.07, 0.14), respectively. Visual and statistical heterogeneity (τ2 = 6.84) was present for pooled analyses of sensitivity and specificity; however, the range in sensitivity values (0.50 to 1.00) was much broader than the range in specificity values (0.86 to 1.00 in all studies except for 1) [Fig. 4 ; Tables 2, 4 and 5].

Most studies used serum or plasma samples. Eight studies had data evaluating five RDTs using capillary or venous whole blood [18, 21, 23, 32, 33, 39, 44, 45], including two that were in exclusively HIV-positive individuals [44, 45]. Pooled sensitivity and specificity in capillary or venous whole blood were comparable to plasma or serum at 91.7% (95% CI: 89.1, 93.9) and 99.9% (95% CI: 99.8, 99.9). Visual and statistical heterogeneity (τ2 = 1.69) were somewhat less among these studies as compared with those described above using a mixture of clinical samples [Fig. 5 ; Tables 2, 4 and 5].

Five studies [26, 44,45,46,47] evaluated three RDTs in 2596 HIV-positive patients, with a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 72.3% (95% CI: 67.9, 76.4) and 99.8% (95% CI: 99.5, 99.9), respectively. Visual and statistical heterogeneity was reduced (τ2 = 1.12). Only one sub-study [18] had extractable data for 224 HIV-negative chronic HBV patients who were HBV treatment naïve [Fig. 6 ; Tables 2, 4 and 5].

Studies published since 2005 reported lower sensitivity compared to the nine articles published before 2005 [20, 27, 30, 32, 33, 36, 38, 40, 42]. Pooled sensitivity was 96.9% (95% CI: 96.0, 97.7) and 86.4% (95% CI: 85.2, 87.5) for studies before and after 2005 respectively [Fig. 7a and b; Table 4]. Five studies [14, 18, 25, 46, 47] published since 2010 evaluating tests against a newer CMIA reference specifically also reported lower pooled sensitivity of 80.4% (95% CI: 77.9, 82.6), with reduced heterogeneity (τ2 = 1.26). Pooled specificity was above 99% irrespective of publication date [Fig. 7b ; Table 5].

Stratifying by test brand did not substantially reduce heterogeneity. Data for all 50 brands of RDTs and EIAs evaluated [Table 5; Additional file 2] demonstrates broad ranges in sensitivity results within individual brands, with generally high (>90%) specificity, as previously noted. Only four test brands were evaluated in three or more studies. Determine HBsAg was evaluated in ten studies, only one published before 2008 [18, 23, 26, 33, 34, 37, 41, 44, 45, 47]; pooled sensitivity and specificity in 7730 samples were 90.8% (95% CI: 88.9, 92.4) and 99.1% (95% CI: 98.9, 99.4), respectively. Excluding one outlier field study that reported a sensitivity of 56% and specificity of 69% [37], the sensitivities ranged from 69% to 100% and specificities from 93% to 100%. VIKIA HBsAg was evaluated in three studies in 5242 patient samples [18, 23, 47], all published after 2010, with pooled sensitivity and specificity of 82.5% (95% CI: 77.5, 86.7) and 99.9% (95% CI: 99.8, 100), respectively. BinaxNOW HBsAg was evaluated in three studies in 3542 patient samples [21, 27, 32], all published before 2007, with pooled sensitivity and specificity of 97.6% (95% CI: 96.2, 98.6) and 100% (95% CI: 99.7, 100), respectively. Serodia HBsAg was evaluated in three studies on 1040 patient samples [33, 38, 42], all published before 2000, with pooled sensitivity and specificity of 95.8% (95% CI: 93.4, 97.5) and 99.8% (95% CI: 99.1, 100), respectively.

Diagnostic accuracy of laboratory immunoassays for HBsAg detection

Five studies [14, 47,48,49,50], performed in China, Ghana, Cambodia and Vietnam evaluated 8 EIAs against a CMIA reference standard, in 1825 serum or plasma samples, reported a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 88.9% (95% CI: 87.0, 90.6) and 98.4% (95% CI: 97.8, 98.8), respectively. The respective positive and negative LRs were 46.8 (95% CI: 12.9, 170.0) and 0.04 (95% CI: 0.01, 0.13), with visible and statistical heterogeneity between studies (τ2 = 12.00). Outliers were from two Chinese studies [14, 49] that evaluated two older ELISA assays (KHB; Wantai) with a sensitivity lower than 90% [Fig. 8 ; Tables 1 and 4].

One study [47] evaluated 3 different EIAs in 838 HIV-positive patients. Results were homogenous between tests, with pooled sensitivity and specificity of 97.9% (95% CI: 96.0, 99.0) and 99.4% (95% CI: 99.0, 99.7), respectively, for a positive and negative LR of 167.3 (95% CI: 95.1, 294.1) and 0.02 (95%CI: 0.01, 0.04) respectively [Table 4].

Diagnostic accuracy compared to a nucleic acid reference standard

Rapid diagnostic tests

Three studies [51,52,53] evaluated 7 RDTs in samples from 510 patients against a NAT reference standard, although some samples were used for multiple testing episodes with different tests. One study [52] used plasma from Nigerian repeat blood donors. Sensitivities ranged from 38% to 99% and specificities ranged from 94 to 99%. Overall pooled sensitivity and specificity were 93.3% (95% CI: 91.3, 94.9) and 98.1% (95% CI: 97.0, 98.9), respectively, with significant heterogeneity in terms of sensitivity [Fig. 9 ; Table 3; Additional file 3]. One case-control study [51] evaluating five different tests in 240 Iranian patients, had significantly higher sensitivity and specificity compared to the other studies, contributing to the overall statistical heterogeneity (τ2 = 5.82).

One study [52] assessed RDT performance in 113 HIV-negative Nigerian repeat blood donors, with clinical sensitivity 60% (95% CI: 36, 81); of note the 8 false negative samples were anti-HBc-positive and regarded as occult hepatitis B, with median HBV viral load 51 IU/ml (range 30–80 IU/mL). The final study [53] had data for consecutive HIV-positive and negative individuals in Uganda; sensitivity was lower in the 83 HIV-positive patients compared to the 74 HIV-negative individuals at 38% (95% CI: 23, 54) and 55% (95% CI: 32, 76) respectively [Table 3; Additional file 3].

Enzyme immunoassays

Five studies [53,54,55,56,57] evaluated EIAs based on a NAT reference, using samples from 1194 patients. Pooled sensitivity and specificity were 75.7% (95% CI: 72.1, 79.1) and 86.1% (95% CI: 83.8, 88.2), respectively. The respective positive and negative LRs were 7.2 (95% CI: 4.4, 11.8) and 0.30 (95%CI: 0.19, 0.46), with reduced heterogeneity compared to studies evaluating RDTs (τ2 = 0.90) [Fig. 10 ; Table 3; Additional file 3].

Three studies [53, 56, 57] had data from 442 HIV-positive patients in Uganda and South Africa, with pooled sensitivity and specificity of 57.9% (95% CI: 49.8, 65.6) and 95.8% (95% CI: 92.7, 97.8), respectively. The corresponding pooled sensitivity and specificity for the 202 HIV-negative patients across two of these studies [53, 57] were 83.3% (95%CI: 69.8, 92.5) and 85.7% (95% CI: 79.2, 90.8), respectively [Table 3; Additional file 3].

Discussion

Study findings

Our systematic review and meta-analysis shows that both RDTs and EIAs had excellent specificity for the detection of HBsAg when compared to laboratory-based assays. Although the pooled sensitivity of RDTs was only 90% compared to laboratory based EIAs, the 10% lower sensitivity of RDTs may be an acceptable trade-off for opportunities to use RDTs to increase access to testing to all levels of the health care system. Significant heterogeneity with a broad range of sensitivity estimates was observed across studies and different brands as well as across studies for the same brand. Accuracy and quality of RDTs should be important considerations in test selection for national programmes.

Apart from the rapid results and ease of use, RDTs can be used with whole blood from a finger prick compared to the necessity of processing blood samples to obtain serum or plasma for use with EIAs. Our review showed that accuracy using capillary or venous whole blood was not significantly different from studies using plasma or serum, which offers convenient specimen sampling outside of laboratory settings without compromising test accuracy.

None of the RDTs met minimum requirements for analytical sensitivity (i.e. limit of detection [LOD] of 0.130 IU/mL) required by regulatory authorities such as the European Union; WHO prequalification assessment studies indicate a 50–100 fold lower LoD for EIAs (0.1 IU/mL) compared to RDTs (2–10 IU/mL) [15]. Clinical sensitivity is however unlikely to be greatly reduced as the majority of chronic HBV is associated with blood HBsAg concentrations well above 10 IU/mL and false-negative HBsAg RDTs are associated with lower HBsAg and viral load, presence of HBsAg mutants, or specific genotypes [15, 23, 34, 47].

We found lower sensitivity of RDTs in HIV-positive individuals; however, there did not appear to be a similar reduction in the single study assessing three different EIAs in this cohort using an EIA reference with neutralisation [47]. The reasons for the apparent lower performance are unclear. Studies quantifying HBsAg found that in the context of co-infection, most false negatives had lower concentrations of HBsAg and generally lower HBV DNA than true positives [46, 47]. HIV-reverse transcriptase inhibitors active against HBV can modestly reduce HBsAg levels and therefore detection by RDTs [58,59,60]; patients treated for a median 47 months demonstrated significantly lower median HBsAg levels compared to untreated patients (3.32log10 vs 4.23log10) (p = 0.001), with the most marked reduction in HBeAg positive patients and those with a more robust improvement of CD4 from nadir on cART [61]. In our review, the two studies with preserved sensitivity were in exclusively ART-naïve patients with median CD4 175 cell/uL [26] and 250 cells/uL [44]. Studies with sensitivity less than 80% were in cohorts which included patients on lamivudine-containing ART [46, 47] or ART-naïve with a higher median CD4 (350 cells/uL) [45]. As most patients in the field will be ART-naïve as part of dual screening programmes, the clinical impact of reduced sensitivity could be less significant as most will have detectable higher HBsAg levels. Another theoretical explanation in the context of ART is that given overlapping surface and polymerase genes, lamivudine with its low genetic barrier to resistance could promote the emergence of surface genome variants undetectable by standard assays; mutations in the “a” antigenic determinant region of HBsAg can cause conformational changes leading to decreased accuracy of diagnosis [62]. This was, however, only a minor contributor to reduced performance in the single study assessing mutants in HIV-HBV co-infection [47], with reduced analytical sensitivity of assays more important. Further reasons for reduced sensitivity of lateral flow devices in the context of HIV could be due to either an increased presence of blocking antibodies to HBsAg and immune-complex formation in HIV-associated hypergammaglobulinaemia, or the prozone effect at high antigen concentrations. Assay sensitivity also varies depending on genotypes, and it could be that regions with high HIV co-infection also have a higher proportion of poorly detected genotypes. Finally, as studies were cross-sectional in nature, we can’t assess and compare the true prevalence of chronic HBV in cohorts or the progression of disease – it may be that there is an increased prevalence of acute and/ or chronic HBV in HIV-cohorts, with RDTs missing low level HBsAg in patients who are in the process of seroconverting from their illness. Further studies are required following up patients with HIV and full HBV serology to further ascertain reasons for and the clinical impact of reduced sensitivity of RDTs.

Accuracy of both HBsAg RDTs and EIAs compared to a NAT reference was generally lower, especially amongst HIV-positive cohorts; sensitivity of RDTs was generally <60%, with one laboratory based case-control study evaluating six RDTs contributing to potential over-estimation of pooled sensitivity [51]. Although NAT assays are not optimal reference standards for HBsAg, given the complex relationship between viral kinetics of HBV DNA and levels of HBsAg, NAT assays are nevertheless useful markers of viremia and disease activity to guide treatment, as well as the detection of occult hepatitis B. Occult hepatitis B (OHB) is defined as the presence of HBV DNA in serum or liver tissue with undetectable HBsAg [57]. Studies in ART-naïve East [63] and West-African [64] patients found an OHB prevalence of 10–15%, with significantly lower HBV viral loads in these individuals compared to those with detectable HBsAg [47]. Knowledge of HBeAg status and ART regimes is relevant, as dually active ART could successfully suppress HBV viral load and HBsAg detection [58, 59]. Now that it is possible to use CMIA to quantitate HBsAg, and levels of HBsAg has been correlated with intrahepatic cccDNA clearance during treatment, further research should explore the use of CMIA to quantitate HBsAg levels as potential markers of disease resolution.

The pooled sensitivity for RDTS in this review is lower than that reported in previous systematic reviews (pooled sensitivities were 97.1% [11], 94.8% [10], and 98.1% [9]). This may be due to the use of different inclusion criteria in the prior reviews. Accuracy estimates tend to be higher when the RDTs were evaluated in laboratory settings using archived evaluation panels than when they are evaluated in field settings in patients attending a clinical facility, who may have a variety of underlying conditions or co-infections that affect test performance. In the case of RDTs, the tests may be stored and used in uncontrolled physical environments and performed by users who may not have ever performed a test. Data on the clinical performance of these assays are more relevant for developing guideline recommendations.

Sources of heterogeneity

Statistical heterogeneity is observed in most diagnostic accuracy reviews. None of the sub-analyses performed eliminated heterogeneity, which could be due to a number of factors. Variability of assays could result in statistical heterogeneity. This persisted despite subgrouping by brand, although it should be noted that the same brand often undergoes minor product changes and modifications over time, particularly with changes in the manufacturer.

Variation in reference standards also contributed to different RDT sensitivity. Pooled sensitivity of RDTs was lower when compared to a CMIA reference standard (80.4%) than a reference including non-CMIA technology (90.0%). ELISA/EIA based assays in particular performed poorly relative to other immunoassays when compared to a CMIA reference [14, 49]; different signal cut-off ratio’s (S/CO) and use of the ‘gray zone’ improved sensitivity at the expense of specificity. Accuracy of tests also varies depending on the phase of chronic HBV infection, with reduced sensitivity more common in the inactive carrier state compared to the active replicative phase. In a Gambian field study [18], the majority (94.7%) of false-negative RDT results were from inactive carriers; they were all HBeAg negative with normal ALT levels, more commonly female (p = 0.05) and had lower median quantitative HBsAg levels compared to true positives (1.2 IU/mL vs 875 IU/mL) (p = 0.0002). Of note, RDTs also had a lower limit of detection in the field (26.5 IU/mL) compared to the laboratory setting (2.8 IU/mL), although the clinical sensitivity was similar, albeit in a study where field staff were all adequately trained. Although inactive carriers often do not warrant treatment, 17% had elevated liver stiffness and were pre-cirrhotic, so would have benefited from antiviral therapy [65]. Further studies are required to assess the clinical impact of reduced RDT sensitivity, particularly those performed in the field.

Finally, the large variability in study design across the literature is a significant source of heterogeneity. A large number of case-control studies with pre-selection of known cases and controls tend to over-estimate accuracy, in part due to the higher quantitative ranges of HBsAg in those with known active disease. Performance in higher income countries tends to be less heterogeneous [11], while reduced accuracy observed in low-resource settings may be due to insufficient training or lack of quality assurance systems [66]. Pooled sensitivity and specificity tend to be lower when the RDTs are used in the field compared to studies where they were performed in laboratory settings [26, 37].

Study strengths

Strengths of this review include evaluation of a comprehensive evidence base, use of a pre-specified protocol incorporating numerous major scientific databases, and assessment of additional areas relevant to HBsAg diagnostic testing, notably comparison with NAT and potential impact of occult hepatitis B. We identified 11 additional articles [18, 22, 25, 28, 29, 35, 37, 43, 45,46,47] not found in the most recent systematic review assessing the diagnostic accuracy of RDTs [11]. The pooled sensitivity for RDTs in this review is lower than reported in previous systematic reviews (pooled sensitivities of 97.1% [11], 94.8% [10], and 98.1% [9]). Potential reasons include the different inclusion criteria; previous reviews included a mixture of studies of analytical performance using serum panels and clinical studies. As previously explained, accuracy estimates tend to be higher when tests are evaluated in laboratory settings using archived evaluation panels, with estimates less relevant for informing the development of testing or operational guidelines.

We included evaluations of both RDTs and EIAs, in addition to evaluation using a NAT reference, and as such are able to evaluate the effects of different types of HBsAg assays and different types of reference assays.

Limitations

Our study has a number of limitations. Many studies were case-control designs or evaluated cohorts known to over-estimate accuracy. We were unable to assess diagnostic accuracy specifically in field studies as definitions of “in the field” are open to interpretation with methods poorly described in many papers. Only two studies (1, 2) specifically mention the use of RDTs in the field. Since the purpose of our review was to assess clinical performance, we included papers describing evaluations of test performance in patients in clinical settings and not laboratory based evaluations using reference panels. Some analyses were based on a small number of patients and few positive samples. We were unable to explore potential sources of heterogeneity due to genotype, stage and severity of infection or other co-infections; genetic information has long been suspected to impact on diagnostic accuracy [67,68,69,70,71,72], and mutants are rapidly evolving such that prevalence of specific types cannot be determined on historical data. The use of different reference standards makes pooling across studies difficult; this is further complicated by rapid changes in technology and analytical sensitivity combined with suboptimal reporting of LOD in both index tests and reference standards. For studies using NAT as a reference, assays were not standardized, with poor reporting of testing, albeit all were according to the manufacturer’s instructions; some used pooled NAT of HBsAg negative sample [55, 57], while others described inadequate detail for qPCR methodology [51, 54]. Finally, the natural history of diagnostic markers in chronic hepatitis B is more complex than most viral infections, with transient low level asynchronous quantitative fluctuations of HBsAg and DNA recognised in uncomplicated chronic HBV [73]. Such cases are clinically less severe and of lower priority than persons with higher levels of viremia, but are likely to impact estimates of sensitivity and specificity.

Implications

The global burden and relative rank of hepatitis B in terms of health loss has increased in the last two decades, unlike most communicable diseases. Implementation of timely and accurate testing strategies in many endemic settings is poor, hindering the linkage to care. Rapid tests are suited to improve the uptake of testing in resource limited settings, particularly amongst remote and vulnerable populations, but evidence is lacking for the impact of testing at the point of care on service delivery and linkage to and uptake of subsequent care. Research is needed on the clinical impact of reduced RDT sensitivity given the association of low quantitative HBsAg missed by testing with inactive carriers and minimal disease progression [74]. Validation of assays in the context of immune escape variants and using less invasive collection methods would support the development of demographic specific testing strategies. Finally, concerns about the low sensitivity of RDTs in HIV positive cohorts warrant particular evaluation, given the growing global challenge posed by co-infection, drug resistance and inadequate approaches to management of HBV and prevention of mother to child transmission in pregnant women [75]. Studies assessing the impact of viral load, CD4 and ART regimen exposure on HBsAg diagnostic accuracy are urgently needed, particularly the potential prudence of repeat HBsAg testing after a certain time in high risk individuals who may have seroconverted or progressed.

Conclusion

In summary, this meta-analysis demonstrates that RDTs to detect HBsAg, performed on either serum, plasma or whole blood, have a pooled sensitivity of >90% and specificity of >98% compared to laboratory methods of HBsAg detection, using EIAs as the reference standard. Sensitivity varies widely overall and within brands of HBsAg tests. Sensitivity of RDTs may be lower in HIV-positive individuals, although possibly less so in ART-naïve individuals who would benefit most from screening using dual HIV-HBV RDTs in settings with limited access to laboratories. Further research is needed to assess the impact of using RDTs in a variety of settings and populations. WHO guidelines currently recommend a role for RDTs in scaling up HBsAg testing in settings with poor access to or lack of existing laboratory infrastructure, such as remote settings or with hard-to-reach populations. Their use may also be appropriate in high-income countries to increase the uptake of hepatitis testing in populations that may be reluctant to test or have poor access to health-care services and in outreach programmes [12].

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

Anti-retroviral therapy

- CC:

-

Case-control studies

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMIAs:

-

Chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassays

- CS:

-

Cross-sectional studies

- DBS:

-

Dried blood spot

- DOR:

-

Diagnostic odds ratio

- ECLIA:

-

Electrochemiluminescent immunoassay

- EIA:

-

Enzyme immunoassay

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- HBcAb:

-

Hepatitis B core antibody

- HBeAg:

-

Hepatitis B ‘e’ antigen

- HBsAg:

-

Hepatitis B surface antigen

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B Virus

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C Virus

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodefiency virus

- LOD:

-

Limit of detection

- LR:

-

Likelihood ratio

- MEIA:

-

Microparticle enzume immunoassay

- NAT:

-

Nucleic acid testing

- NLR:

-

Negative likelihood ratio

- PLR:

-

Positive likelihood ratio

- POC:

-

Point-of-care

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- QUADAS:

-

Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies

- RDTs:

-

Rapid diagnostic tests

- REM:

-

Random effects model

- RIA:

-

Radioimmunoassay

- S/CO:

-

Signal cut-off ratio’s

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Global hepatitis report 2017. 2017: Geneva. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/global-hepatitis-report2017/en/

Ganem D, Prince AM, Hepatitis B. Virus infection--natural history and clinical consequences. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1118–29.

Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117–71.

Stanaway JD, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Fitzmaurice C, Vos T, Abubakar I, et al. The global burden of viral hepatitis from 1990 to 2013: findings from the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388(10049):1081–8.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. 2015: Geneva. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/hepatitis/hepatitis-b-guidelines/en/

Fabrizi F, Martin P, Dixit V, Bunnapradist S, Dulai G. Meta-analysis: the effect of age on immunological response to hepatitis B vaccine in end-stage renal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(10):1053–62.

Thompson Coon J, Rogers G, Hewson P, Wright D, Anderson R, Cramp M, et al. Surveillance of cirrhosis for hepatocellular carcinoma: systematic review and economic analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(34):1–206.

Qin XK, Li P, Han M, Liu JP. Xiaochaihu tang for treatment of chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review of randomized trials. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2010;8(4):312–20.

Hwang SH, HB O, Choi SE, Kim HH, Chang CL, Lee EY, et al. Meta-analysis for the pooled sensitivity and specificity of hepatitis B surface antigen rapid tests. Korean journal of. Lab Med. 2008;28(2):160–8.

Shivkumar S, Peeling R, Jafari Y, Joseph L, Pai NP. Rapid point-of-care first-line screening tests for hepatitis B infection: a meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy (1980-2010). Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(9):1306–13.

Khuroo NS, Khuroo MS. Accuracy of rapid point-of-care diagnostic tests for hepatitis B surface antigen-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical & Experimental. Hepatology. 2014;4(3):226–40.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing. 2017: Geneva. http://www.who.int/hepatitis/publications/guidelines-hepatitis-c-b-testing/en/

World Health Organization. Hepatitis B surface antigen assays: operational characteristics (phase I) Report 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Liu C, Chen T, Lin J, Chen H, Chen J, Lin S, et al. Evaluation of the performance of four methods for detection of hepatitis B surface antigen and their application for testing 116,455 specimens. J Virol Methods. 2014;196:174–8.

Scheiblauer H, El-Nageh M, Diaz S, Nick S, Zeichhardt H, Grunert HP, et al. Performance evaluation of 70 hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg) assays from around the world by a geographically diverse panel with an array of HBV genotypes and HBsAg subtypes.[Erratum appears in Vox sang. 2010 may;98(4):581]. Vox Sang. 2010;98(3 Pt 2):403–14.

Deguchi M, Yamashita N, Kagita M, Asari S, Iwatani Y, Tsuchida T, et al. Quantitation of hepatitis B surface antigen by an automated chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay. J Virol Methods. 2004;115(2):217–22.

Cornberg M, Wong VW, Locarnini S, Brunetto M, Janssen HL, Chan HL. The role of quantitative hepatitis B surface antigen revisited. J Hepatol. 2017; 66(2):398–411.

Njai HF, Shimakawa Y, Sanneh B, Ferguson L, Ndow G, Mendy M, et al. Validation of rapid point-of-care (POC) tests for detection of hepatitis B surface antigen in field and laboratory settings in the Gambia, Western Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(4):1156–63.

Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–36.

Abraham P, Sujatha R, Raghuraman S, Subramaniam T, Sridharan G. Evaluation of two immunochromatographic assays in relation to ‘RAPID’ screening of HBsAg. Indian J Med Microbiol. 1998;16:23–5.

Akanmu AS, Esan OA, Adewuyi JO, Davies AO, Okany CC, Olatunji RO, et al. Evaluation of a rapid test kit for detection of HBsAg/eAg in whole blood: a possible method for pre-donation testing. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2006;35(1):5–8.

Bjoerkvoll B, Viet L, Ol HS, Lan NT, Sothy S, Hoel H, et al. Screening test accuracy among potential blood donors of HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HCV to detect hepatitis B and C virus infection in rural Cambodia and Vietnam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41(5):1127–35.

Bottero J, Boyd A, Gozlan J, Lemoine M, Carrat F, Collignon A, et al. Performance of rapid tests for detection of HBsAg and anti-HBsAb in a large cohort, France. J Hepatol. 2013;58(3):473–8.

Chameera EWS, Noordeen F, Pandithasundara H, Abeykoon AMSB. Diagnostic efficacy of rapid assays used for the detection of hepatitis B virus surface antigen. Sri Lankan. J Infect Dis. 2013;3(2):21–7.

Chevaliez S, Challine D, Naija H, Luu TC, Laperche S, Nadala L, et al. Performance of a new rapid test for the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen in various patient populations. J Clin Virol. 2014;59(2):89–93.

Davies J, van Oosterhout JJ, Nyirenda M, Bowden J, Moore E, Hart IJ, et al. Reliability of rapid testing for hepatitis B in a region of high HIV endemicity. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2010;104(2):162–4.

Clement F, Dewint P, Leroux-Roels G. Evaluation of a new rapid test for the combined detection of hepatitis B virus surface antigen and hepatitis B virus e antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(12):4603–6.

Erhabor O, Kwaifa I, Bayawa A, Isaac Z, Dorcas IaS, I. Comparison of ELISA and rapid screening techniques for the detection of HBsAg among blood donors in Usmanu Danfodiyo university teaching hospital Sokoto, North Western Nigeria. J Blood Lymph. 2014;4(2):124.

Gish RG, Gutierrez JA, Navarro-Cazarez N, Giang K, Adler D, Tran B, et al. A simple and inexpensive point-of-care test for hepatitis B surface antigen detection: serological and molecular evaluation. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21(12):905–8.

Kaur H, Dhanao J, Oberoi A. Evaluation of rapid kits for detection of HIV, HBsAg and HCV infections. Indian J Med Sci. 2000;54(10):432–4.

Khan J, Lone D, Hameed A. Evaluation of the performance of two rapid immunochromatographic tests for detection of hepatitis B surface antigen and anti HCV antibodies using ELISA tested samples. AKEMU. 2010;16(1 S1):84–7.

Lau DT, Ma H, Lemon SM, Doo E, Ghany MG, Miskovsky E, et al. A rapid immunochromatographic assay for hepatitis B virus screening. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10(4):331–4.

Lien TX, Tien NTK, Chanpong GF, Cuc CT, Yen VT, Soderquist R, et al. Evaluation of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2, hepatitis B surface antigen, and syphilis in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62(2):301–9.

Lin YH, Wang Y, Loua A, Day GJ, Qiu Y, Nadala EC Jr, et al. Evaluation of a new hepatitis B virus surface antigen rapid test with improved sensitivity. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(10):3319–24.

Mutocheluh M, Owusu M, Kwofie TB, Akadigo T, Appau E, Narkwa PW. Risk factors associated with hepatitis B exposure and the reliability of five rapid kits commonly used for screening blood donors in Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:873.

Mvere D, Constantine NT, Katsawde E, Tobaiwa O, Dambire S, Corcoran P. Rapid and simple hepatitis assays: encouraging results from a blood donor population in Zimbabwe. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74(1):19–24.

Nyirenda M, Beadsworth MB, Stephany P, Hart CA, Hart IJ, Munthali C, et al. Prevalence of infection with hepatitis B and C virus and coinfection with HIV in medical inpatients in Malawi. J Infect. 2008;57(1):72–7.

Oh J, Kim TY, Yoon HJ, Min HS, Lee HR, Choi TY. Evaluation of Genedia® HBsAg rapid and Genedia® anti-HBs rapid for the screening of HBsAg and anti-HBs. Korean J Clin Pathol. 1999;19:114–7.

Ola SO, Otegbayo JA, Yakubu A, Aje AO, Odaibo GN, Shokunbi W. Pitfalls in diagnosis of hepatitis B virus infection among adults nigerians. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12(4):350–4.

Raj AA, Subramaniam T, Raghuraman S, Abraham P. Evaluation of an indigenously manufactured rapid immunochromatographic test for detection of HBsAg. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44(4):413–4.

Randrianirina F, Carod JF, Ratsima E, Chretien JB, Richard V, Talarmin A. Evaluation of the performance of four rapid tests for detection of hepatitis B surface antigen in Antananarivo, Madagascar. J Virol Methods. 2008;151(2):294–7.

Sato K, Ichiyama S, Iinuma Y, Nada T, Shimokata K, Nakashima N. Evaluation of immunochromatographic assay systems for rapid detection of hepatitis B surface antigen and antibody, Dainascreen HBsAg and Dainascreen Ausab. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(6):1420–2.

Upreti SR, Gurung S, Patel M, Dixit SM, Krause LK, Shakya G, et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection before and after implementation of a hepatitis B vaccination program among children in Nepal. Vaccine. 2014;32(34):4304–9.

Franzeck FC, Ngwale R, Msongole B, Hamisi M, Abdul O, Henning L, et al. Viral hepatitis and rapid diagnostic test based screening for HBsAg in HIV-infected patients in rural Tanzania. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e58468.

Hoffmann CJ, Dayal D, Cheyip M, McIntyre JA, Gray GE, Conway S, et al. Prevalence and associations with hepatitis B and hepatitis C infection among HIV-infected adults in South Africa. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(10):e10–3.

Honge BL, Jespersen S, Te DS, da Silva ZJ, Laursen AL, Krarup H, et al. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen and anti-hepatitis C virus rapid tests underestimate hepatitis prevalence among HIV-infected patients. HIV Med. 2014;15(9):571–6.

Geretti AM, Patel M, Sarfo FS, Chadwick D, Verheyen J, Fraune M, et al. Detection of highly prevalent hepatitis B virus coinfection among HIV-seropositive persons in Ghana. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(9):3223–30.

Ol HS, Bjoerkvoll B, Sothy S, Van Heng Y, Hoel H, Husebekk A, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in potential blood donors in rural Cambodia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2009;40(5):963–71.

Peng J, Cheng L, Yin B, Guan Q, Liu Y, Wu S, et al. Development of an economic and efficient strategy to detect HBsAg: application of “gray-zones” in ELISA and combined use of several detection assays. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(23–24):2046–51.

Viet L, Lan NT, Ty PX, Bjorkvoll B, Hoel H, Gutteberg T, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B & hepatitis C virus infections in potential blood donors in rural Vietnam. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136(1):74–81.

Ansari MHK, Omrani MD, Movahedi V. Comparative evaluation of immunochromatographic rapid diagnostic tests (strip and device) and PCR methods for detection of human hepatitis B surface antigens. Hepat Mon. 2007;7(2):87–91.

Nna E, Mbamalu C, Ekejindu I. Occult hepatitis B viral infection among blood donors in south-eastern Nigeria. Pathogens Global Health. 2014;108(5):223–8.

Seremba E, Ocama P, Opio CK, Kagimu M, Yuan HJ, Attar N, et al. Validity of the rapid strip assay test for detecting HBsAg in patients admitted to hospital in Uganda. J Med Virol. 2010;82(8):1334–40.

Khadem-Ansari MH, Omrani MD, Rasmi Y, Ghavam A. Diagnostic validity of the chemiluminescent method compared to polymerase chain reaction for hepatitis B virus detection in the routine clinical diagnostic laboratory. Adv Biomed Res. 2014;3:116.

Olinger CM, Weber B, Otegbayo JA, Ammerlaan W, van der Taelem-Brule N, Muller CP. Hepatitis B virus genotype E surface antigen detection with different immunoassays and diagnostic impact of mutations in the preS/S gene. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2007;196(4):247–52.

Lukhwareni A, Burnett RJ, Selabe SG, Mzileni MO, Mphahlele MJ. Increased detection of HBV DNA in HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-negative south African HIV/AIDS patients enrolling for highly active antiretroviral therapy at a tertiary hospital. J Med Virol. 2009;81(3):406–12.

Mphahlele MJ, Lukhwareni A, Burnett RJ, Moropeng LM, Ngobeni JM. High risk of occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-positive patients from South Africa. J Clin Virol. 2006;35(1):14–20.

Brunetto MR, Moriconi F, Bonino F, Lau GKK, Farci P, Yurdaydin C, et al. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: a guide to sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1141–50.

Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1):132–43.

Brunetto MR, Oliveri F, Colombatto P, Moriconi F, Ciccorossi P, Coco B, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen serum levels help to distinguish active from inactive hepatitis B virus genotype D carriers. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(2):483–90.

Jaroszewicz J, Reiberger T, Meyer-Olson D, Mauss S, Vogel M, Ingiliz P, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen concentrations in patients with HIV/HBV co-infection. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43143.

Sadeghi A, Shirvani-Dastgerdi E, Tacke F, Yagmur E, Poortahmasebi V, Poorebrahim M, et al. HBsAg mutations related to occult hepatitis B virus infection in HIV-positive patients result in a reduced secretion and conformational changes of HBsAg. J Med Virol. 2017;89(2):246–56.

Mudawi H, Hussein W, Mukhtar M, Yousif M, Nemeri O, Glebe D, et al. Overt and occult hepatitis B virus infection in adult Sudanese HIV patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;29:65–70.

N'Dri-Yoman T, Anglaret X, Messou E, Attia A, Polneau S, Toni T, et al. Occult HBV infection in untreated HIV-infected adults in cote d’Ivoire. Antivir Ther. 2010;15(7):1029–34.

European Association For The Study Of The L. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57(1):167–85.

Pruett CR, Vermeulen M, Zacharias P, Ingram C, Tayou Tagny C, Bloch EM. The use of rapid diagnostic tests for transfusion infectious screening in Africa: a literature review. Transfus Med Rev. 2015;29(1):35–44.

Moerman B, Moons V, Sommer H, Schmitt Y, Stetter M. Evaluation of sensitivity for wild type and mutant forms of hepatitis B surface antigen by four commercial HBsAg assays. Clin Lab. 2004;50(3–4):159–62.

Ly TD, Servant-Delmas A, Bagot S, Gonzalo S, Ferey MP, Ebel A, et al. Sensitivities of four new commercial hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) assays in detection of HBsAg mutant forms. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(7):2321–6.

Mizuochi T, Okada Y, Umemori K, Mizusawa S, Yamaguchi K. Evaluation of 10 commercial diagnostic kits for in vitro expressed hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigens encoded by HBV of genotypes A to H. J Virol Methods. 2006;136(1–2):254–6.

Kuhns MC, McNamara AL, Holzmayer V, Lou SC, Busch MP. Frequency of diagnostically significant hepatitis B surface antigen mutants. J Med Virol. 2007;79(SUPPL. 1):S42–S6.

Zhang R, Wang L, Li J. Hepatitis B virus transfusion risk in China: proficiency testing for the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen. Transfus Med. 2010;20(5):322–8.

Servant-Delmas A, Mercier-Darty M, Ly TD, Wind F, Alloui C, Sureau C, et al. Variable capacity of 13 hepatitis B virus surface antigen assays for the detection of HBsAg mutants in blood samples. J Clin Virol. 2012;53(4):338–45.

Maylin S, Sire JM, Mbaye PS, Simon F, Sarr A, Evra ML, et al. Short-term spontaneous fluctuations of HBV DNA levels in a Senegalese population with chronic hepatitis B. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):154.

Liu J, Yang HI, Lee MH, Jen CL, Batrla-Utermann R, SN L, et al. Serum levels of hepatitis B surface antigen and DNA can predict inactive carriers with low risk of disease progression. Hepatology. 2016;64(2):381–9.

Kourtis AP, Bulterys M, DJ H, Jamieson DJ. HIV-HBV coinfection - a global challenge. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(19):1749–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of WHO, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, SESH Global and UNC Project China.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is included within the article’s additional file.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Infectious Diseases Volume 17 Supplement 1, 2017: Testing for chronic hepatitis B and C – a global perspective. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-17-supplement-1.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the World Health Organization to RP at LSHTM, National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases 1R01AI114310–01 to JT, and UNC-South China STD Research Training Centre Fogarty International Centre 1D43TW009532–01 to JT.

Publication charges for this article have been funded by the World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RP and JDT designed the study, with input from JF in building search algorithm and retrieving articles. All authors contributed to study optimisation. AA, HK and OV identified and extracted data. AA was responsible for overall data synthesis and wrote the manuscript with input from OV, JT and RP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Search strategy. (DOC 80 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S1.

Summary pooled diagnostic accuracy of HBsAg assays by brand. (DOC 126 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S2.

Summary pooled diagnostic accuracy of HBsAg assays using NAT reference standards. (DOC 75 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/legalcode), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. In any reproduction of this article there should not be any suggestion that WHO or this article endorse any specific organization or products. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. This notice should be preserved along with the article's original URL.

About this article

Cite this article

Amini, A., Varsaneux, O., Kelly, H. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of tests to detect hepatitis B surface antigen: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 17 (Suppl 1), 698 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2772-3

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-017-2772-3