Abstract

Background

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine antibody response has been associated with reduced risk of AIDS or death. However, it is unknown whether HBV vaccine responsiveness is associated with improved immune reconstitution during treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). We evaluated the relationship between HBV vaccine response status and CD4 reconstitution on cART in the U.S Military HIV Natural History Study.

Methods

Participants with viral load <400 copies/mL within 1 year on initial cART and documented HBV vaccination and surface antibody (anti-HBs) prior to cART were included. Participants were characterized as HBV vaccine responders (anti-HBs ≥10 IU/L) or non-responders (<10 IU/L) and further divided into 2 groups based on vaccine administration before or after HIV diagnosis. Linear mixed regression was used to model CD4 reconstitution during the first year of cART.

Results

Of the 307 and 169 participants vaccinated before or after HIV diagnosis, HBV vaccine response occurred in 288 (94%) and 74 (44%), respectively. For those vaccinated before HIV diagnosis, CD4 counts increased by a median 190 [IQR 99–310] cells/mm3 for responders and 186 [IQR 116–366] cells/mm3 for non-responders during the first year (P = 0.684). Participants vaccinated after HIV diagnosis had median increases of 185 [IQR 76–270] and 143 [IQR 47–238] cells/mm3 for responders and non-responders, respectively (P = 0.134). In contrast to those with CD4 > 350 cells/mm3 at cART initiation, participants with CD4 < 200 and 200–350 cells/mm3 had significantly reduced CD4 gains in both groups by longitudinal mixed models, but there was no difference in CD4 recovery according to HBV vaccine seroresponse.

Conclusions

Although HBV vaccine responsiveness is associated with a reduction in HIV disease progression, HBV vaccine responders do not achieve greater CD4 gains during the first year of cART. Additional clinical markers are needed to predict the magnitude of post-cART immune recovery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the setting of HIV infection, immunization with hepatitis B virus (HBV) vaccine is essential in order to prevent liver-related morbidity and mortality than can occur with HBV co-infection [1,2]. However, HIV-infected patients have diminished vaccine responsiveness compared to HIV-uninfected persons [3-6]. For example, positive seroresponses occur in 20-62% of persons vaccinated after HIV diagnosis compared to approximately 90% in HIV-uninfected individuals. The development of a positive HBV vaccine antibody response involves not only T-cell function but also other functional pathways including B-cell activity and antigen presentation of the peptide-based vaccine [7-9]. Since HBV vaccine seroresponse requires preserved function in a number of immune pathways, the evaluation of vaccine responsiveness in HIV-infected persons may provide useful information about the immune status of the individual beyond measurement of CD4 cell counts.

In a previous study, we reported the risk of developing clinical acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) or death is 2-fold higher in HBV vaccine non-responders compared to responders after adjusting for HIV disease-related factors such as CD4 count, viral load (VL), and use of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) [10]. Although HBV vaccine response can predict HIV disease outcomes, it is unknown whether HBV vaccine responders have improved immune recovery during cART. Identifying predictors of CD4 reconstitution during cART is clinically important since the rate of both AIDS and serious non-AIDS events decrease at higher CD4 counts, even among the subgroup of individuals with CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3 [11,12]. We retrospectively evaluated the relationship between HBV vaccine response status and post-cART CD4 cell gains in the U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study.

Methods

The U.S. Military HIV Natural History Study is comprised of over 5700 military beneficiaries with HIV infection as previously described [13]. Participants were ≥18 years of age and provided informed, written consent. Individuals without prior HBV infection who achieved VL suppression, defined as <400 copies/mL within 1 year on their initial cART regimen, and maintained VL suppression for >1 year were included. Participants were divided into 2 groups according to the whether all vaccine doses were received prior to HIV diagnosis or in the interval between HIV diagnosis and cART initiation. Individuals who received HBV vaccine doses both before and after HIV diagnosis were excluded as were individuals vaccinated after cART initiation. Participants were then characterized according to HBV vaccine response, with responders and non-responders defined as having an antibody to HBV surface antigen (anti-HBs) ≥10 or <10 IU/L, respectively ≥30 days after last vaccination. For those vaccinated prior to HIV diagnosis, the first available anti-HBs determination was used to assign participants into responder or non-responder categories. This study was approved by the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

The primary outcome was CD4 cell recovery during the first year of cART in HBV vaccine responders compared to non-responders. Continuous variables were analyzed by t-test for normally distributed variables and Wilcoxon for non-normally distributed variables. Normality was assessed using Shapiro-Wilks test. P-values for categorical variables were calculated using chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. To assess and quantify the effect of HBV vaccine response on CD4 reconstitution after cART initiation, all available CD4 counts for participants from cART initiation to one year post-cART were analyzed. To quantify the adjusted effect of vaccine response on the rate of CD4 increase after cART, longitudinal mixed models were performed which allowed use of all CD4 values in the window of interest while accounting for within participant CD4 association. The model adjusts for race, gender, age at cART initiation, AIDS before cART, and HBV vaccine response status at baseline as well as CD4 at cART and vaccine response status on CD4 gains after cART. Power to detect differences among variables was enhanced by multiple CD4 count measurements contributed per participant. Lastly, sensitivity analyses were performed for several variables, including year of cART initiation, and time from HIV diagnosis to cART initiation. Additional variables were used to assess effect modification post hoc, however none of these variables were significant modifiers for the outcome of interest.

Results

A total of 307 participants met criteria for HBV vaccination prior to HIV diagnosis, including 288 (94%) responders and 19 (6%) non-responders (Table 1). Demographic characteristics were similar between groups except the responder group had a higher proportion of African Americans. The median CD4 count at cART initiation was 360 [IQR 270–448] cells/mm3 compared to 298 [IQR 234–394] cells/mm3 for responders versus non-responders (P = 0.398), respectively and VL was similar between groups. Participants vaccinated prior to HIV diagnosis had a median of 4 (IQR 2–5) CD4 count determinations during the first year on cART and a median of 3 (IQR 2–5) values were available for those vaccinated between HIV diagnosis and cART initiation. Regimens commonly included non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) in both groups, however the median year of cART initiation was later for responders compared to non-responders (2008 vs 2003; P = 0.051).

For participants vaccinated after HIV diagnosis but prior to cART initiation (n = 169), 74 (44%) were responders and 95 (56%) were non-responders. Demographic and vaccine-related characteristics were similar between groups, including the number of vaccine doses, and CD4 and VL at the time of last vaccination. At cART initiation, the median CD4 count (390 [IQR 277–492] vs 377 [IQR 215–460] cells/mm3; P = 0.137) and median VL (4.4 [IQR 3.9-4.7] vs 4.4 [IQR 3.5-4.8] log10 copies/mL; P = 0.864) were not different for responders compared to non-responders, respectively. Responders initiated cART at a later median calendar year compared to non-responders (2004 vs. 1998; P = 0.001) and the majority of participants in both groups received protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimens.

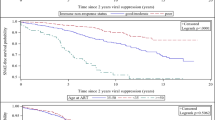

Among those vaccinated before HIV diagnosis, the median CD4 cell gains 1 year post-cART were similar for HBV vaccine responders compared to non-responders (190 [IQR 99–310] cells/mm3 vs. 186 [IQR 116–366] cells/mm3; P = 0.684, respectively). For participants vaccinated after HIV diagnosis, vaccine responders had greater CD4 gains (185 [IQR 76–270] cells/mm3) compared to non-responders (143 [IQR 47–238] cells/mm3), however the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.134). Longitudinal mixed models for CD4 gains during the first year of cART (Table 2) showed that CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 at cART initiation was associated with reduced CD4 gains for those vaccinated before (−208 cells/mm3, 95% CI −283, −134; P < 0.001) and after HIV diagnosis (−188 cells/mm3, 95% CI −295, −81; P < 0.001). A similar effect was also observed for participants with pre-cART CD4 counts between 200–350 cells/mm3 for those vaccinated before or after HIV diagnosis (−141 cells/mm3, 95% CI −189, −94; P < 0.001 and −81 cells/mm3, −167, 5; P = 0.067, respectively). HBV vaccine responder status was not associated with greater CD4 recovery in those vaccinated either before (−18 cells/mm3, 95% CI −79, 42; P = 0.551) or after HIV diagnosis (26 cells/mm3, 95% CI −55, 108; P = 0.528).

Discussion

In addition to the importance of HBV vaccine in the prevention of HBV infection, positive vaccine response has been associated with improved HIV prognosis. In a previous study, we found that 22% of HBV vaccine non-responders developed AIDS or death compared to 5% of responders (P < 0.001) [10]. Based on these findings, we studied whether the beneficial functional immune aspects inherent in vaccine responders translated to more robust immune responses after initiation of VL-suppressive cART. Characteristics associated with differential CD4 gains on cART in previous studies were no different among our participant groups, including age, regimen type, duration of HIV infection, and pre-cART CD4 counts and VL [14-16]. In accordance with prior studies in our cohort [13,17], we observed that CD4 gains were blunted in those with lower CD4 cell counts at cART initiation, particularly in those with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3. However, the magnitude of CD4 gains was comparable for HBV vaccine responders compared to non-responders regardless of whether participants were vaccinated before or after HIV diagnosis. Although HBV vaccine seroresponse did not predict CD4 reconstitution after cART initiation, response status remains an important tool as a reduction in AIDS or death events was observed in vaccine responders independent of CD4 cell count in our prior study, including those with CD4 counts >500 cells/mm3.

The immunity represented by CD4 count may not be fully indicative of immune functions that lead to the production of anti-HBs antibodies at an effective titer. In addition to our current study examining CD4 outcomes by HBV vaccine seroresponse, studies of other HIV prognostic markers demonstrated similar findings. For example, delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) response to recall antigens, an assessment of cell-mediated immunity, has been associated with HIV disease progression [18,19]. However, pre-cART DTH responsiveness did not predict CD4 gains during VL-suppressive cART [20]. Discordance between CD4 count and HIV clinical outcomes was observed in the SILCAAT and ESPIRIT studies [21]. In these clinical trials, infusion of interleukin-2 (IL-2) in addition to cART resulted in larger, sustained CD4 gains compared to cART alone. However, the increase in CD4 count did not translate to improved clinical outcomes as measured by development of opportunistic infections or death, as there was no difference in these outcomes in those treated with cART plus IL-2 compared to cART alone. The observation of nearly identical CD4 gains for HBV vaccine responders and non-responders during the first year of cART in our current study may be explained by differing pathways involved in CD4 reconstitution during cART compared to those responsible for development of HBV vaccine seroresponse.

The strengths of this study include a population with early enrolment after HIV infection and free access to care, as these can be confounders in other cohorts. Based on the composition of our military cohort, our findings may not be applicable to women or those with a history of intravenous drug use or HCV co-infection. The magnitude of anti-HBs titers were not examined as quantitative titers were not routinely performed in clinical practice. Other limitations include the retrospective study design and non-randomized administration of HBV vaccine either before or after HIV diagnosis. The vaccine manufacturer and dose administered were not recorded, however there are conflicting data regarding the efficacy of high-dose HBV in HIV-infected persons [22,23]. The decision to initiate cART was non-randomized and at the discretion of individual providers and patients. Although cART regimens were compared by drug class, specific regimens could not be directly compared due to sample size constraints.

Conclusions

We observed no difference in CD4 gains for HBV vaccine responders compared to non-responders by the examination of CD4 gains at 1 year post-cART and by longitudinal mixed modeling of all CD4 values during the first year of therapy. This lack of effect was observed in those vaccinated before or after HIV diagnosis. Since HBV vaccine responsiveness has been associated with reduced risk of AIDS or death, it is possible that vaccine responders may have improved immune recovery during cART that is not measured by CD4 counts. For example, T-cell activation and exhaustion, which have both been associated with HIV disease progression and death, may continue to have detrimental effects during VL-suppressive cART [24,25]. The development and validation of other clinically relevant immune correlates are necessary to better predict both HIV progression and immune recovery during cART.

Abbreviations

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- VL:

-

Viral load

- cART:

-

Combination antiretroviral therapy

- Anti-HBs:

-

Antibody to HBV surface antigen

- NNRTI:

-

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor

- PI:

-

Protease inhibitor

- DTH:

-

Delayed-type hypersensitivity

- IL-2:

-

Interleukin 2

References

Kim JH, Psevdos Jr G, Sharp V. Five-year review of HIV-hepatitis B virus (HBV) co-infected patients in a New York City AIDS center. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27(7):830–3.

Anderson AM, Mosunjac MB, Palmore MP, Osborn MK, Muir AJ. Development of fatal acute liver failure in HIV-HBV coinfected patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(32):4107–11.

Landrum ML, Fieberg AM, Chun HM, Crum-Cianflone NF, Marconi VC, Weintrob AC, et al. The effect of human immunodeficiency virus on hepatitis B virus serologic status in co-infected adults. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8687.

Irungu E, Mugo N, Ngure K, Njuguna R, Celum C, Farquhar C, et al. Immune response to hepatitis B virus vaccination among HIV-1 infected and uninfected adults in Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(3):402–10.

Tsai IJ, Chang MH, Chen HL, Ni YH, Lee PI, Chiu TY, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of the combined hepatitis A and B vaccine in young adults. Vaccine. 2000;19(4–5):437–41.

Collier AC, Corey L, Murphy VL, Handsfield HH. Antibody to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and suboptimal response to hepatitis B vaccination. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(2):101–5.

van den Berg R, van Hoogstraten I, van Agtmael M. Non-responsiveness to hepatitis B vaccination in HIV seropositive patients; possible causes and solutions. AIDS Rev. 2009;11(3):157–64.

Yao ZQ, Moorman JP. Immune exhaustion and immune senescence: two distinct pathways for HBV vaccine failure during HCV and/or HIV infection. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2013;61(3):193–201.

Goncalves L, Albarran B, Salmen S, Borges L, Fields H, Montes H, et al. The nonresponse to hepatitis B vaccination is associated with impaired lymphocyte activation. Virology. 2004;326(1):20–8.

Landrum ML, Hullsiek KH, O'Connell RJ, Chun HM, Ganesan A, Okulicz JF, et al. Hepatitis B vaccine antibody response and the risk of clinical AIDS or death. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33488.

Marin B, Thiebaut R, Bucher HC, Rondeau V, Costagliola D, Dorrucci M, et al. Non-AIDS-defining deaths and immunodeficiency in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2009;23(13):1743–53.

Mocroft A, Furrer HJ, Miro JM, Reiss P, Mussini C, Kirk O, et al. The incidence of AIDS-defining illnesses at a current CD4 count >/= 200 cells/muL in the post-combination antiretroviral therapy era. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57(7):1038–47.

Marconi VC, Grandits GA, Weintrob AC, Chun H, Landrum ML, Ganesan A, et al. Outcomes of highly active antiretroviral therapy in the context of universal access to healthcare: the U.S. Military HIV natural history study. AIDS Res Ther. 2010;7:14.

Kaufmann GR, Furrer H, Ledergerber B, Perrin L, Opravil M, Vernazza P, et al. Characteristics, determinants, and clinical relevance of CD4 T cell recovery to <500 cells/microL in HIV type 1-infected individuals receiving potent antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(3):361–72.

Gilson RJ, Man SL, Copas A, Rider A, Forsyth S, Hill T, et al. Discordant responses on starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: suboptimal CD4 increases despite early viral suppression in the UK collaborative HIV cohort (UK CHIC) study. HIV Med. 2010;11(2):152–60.

Jevtovic D, Salemovic D, Ranin J, Pesic I, Zerjav S, Djurkovic-Djakovic O. The dissociation between virological and immunological responses to HAART. Biomed Pharmacother. 2005;59(8):446–51.

Kulkarni H, Okulicz JF, Grandits G, Crum-Cianflone NF, Landrum ML, Hale B, et al. Early postseroconversion CD4 cell counts independently predict CD4 cell count recovery in HIV-1-postive subjects receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(5):387–95.

Dolan MJ, Clerici M, Blatt SP, Hendrix CW, Melcher GP, Boswell RN, et al. In vitro T cell function, delayed-type hypersensitivity skin testing, and CD4+ T cell subset phenotyping independently predict survival time in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Infect Dis. 1995;172(1):79–87.

Blatt SP, Hendrix CW, Butzin CA, Freeman TM, Ward WW, Hensley RE, et al. Delayed-type hypersensitivity skin testing predicts progression to AIDS in HIV-infected patients. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(3):177–84.

Minidis NM, Mesner O, Agan BK, Okulicz JF. Delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) test anergy does not impact CD4 reconstitution or normalization of DTH responses during antiretroviral therapy. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18799.

Group I-ES, Committee SS, Abrams D, Levy Y, Losso MH, Babiker A, et al. Interleukin-2 therapy in patients with HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1548–59.

Cornejo-Juarez P, Volkow-Fernandez P, Escobedo-Lopez K, Vilar-Compte D, Ruiz-Palacios G, Soto-Ramirez LE. Randomized controlled trial of Hepatitis B virus vaccine in HIV-1-infected patients comparing two different doses. AIDS Res Ther. 2006;3:9.

Fonseca MO, Pang LW, de Paula CN, Barone AA, Heloisa Lopes M. Randomized trial of recombinant hepatitis B vaccine in HIV-infected adult patients comparing a standard dose to a double dose. Vaccine. 2005;23(22):2902–8.

Guihot A, Bourgarit A, Carcelain G, Autran B. Immune reconstitution after a decade of combined antiretroviral therapies for human immunodeficiency virus. Trends Immunol. 2011;32(3):131–7.

Wilson EM, Sereti I. Immune restoration after antiretroviral therapy: the pitfalls of hasty or incomplete repairs. Immunol Rev. 2013;254(1):343–54.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the NIH or the Department of Health and Human Services, the DoD or the Departments of the Army, Navy or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Support for this work (IDCRP-000-03) was provided by the Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program (IDCRP), a Department of Defense (DoD) program executed through the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. This project has been funded in whole, or in part, with federal funds from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health (NIH), under Inter-Agency Agreement Y1-AI-5072.

Authors’ contributions

KA, OM, AG, TAO, RGD, BKA, and JFO participated in the design of the study and manuscript preparation. OM performed the statistical analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Allen, K., Mesner, O., Ganesan, A. et al. Association between hepatitis B vaccine antibody response and CD4 reconstitution after initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons. BMC Infect Dis 15, 203 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0937-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-015-0937-5