Abstract

Background

We sought to determine if nasopharyngeal (NP) cultures taken at times of healthy visits or at onset of acute otitis media (AOM) could predict the otopathogen mix and antibiotic-susceptibility of middle ear isolates as determined by middle ear fluid (MEF) cultures obtained by tympanocentesis.

Methods

During a 7-year-prospective study of 619 children from Jun 2006-Aug 2013, NP cultures were obtained from 6-30 month olds at healthy visits and NP and MEF (by tympanocentesis) at onset of AOM episodes.

Results

2601 NP and 530 MEF samples were collected. During healthy visits, S. pneumoniae (Spn) was isolated from 656 (31.7%) NP cultures compared to 253 (12.2%) for Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and 723 (34.9%) for Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat). At onset of AOM 256 (48.3%) of 530 NP samples were culture positive for Spn, 223 (42%) for NTHi and 251 (47.4%) for Mcat, alone or in combinations. At 530 AOM visits, Spn was isolated from 152 (28.7%) of MEF compared to 196 (37.0%) for NTHi and 104 (19.6%) for Mcat. NP cultures collected at onset of AOM but not when children were healthy had predictive value for epidemiologic antibiotic susceptibility pattern assessments.

Conclusions

NP cultures at onset of AOM more closely correlate with otopathogen mix than NP cultures at healthy visits using MEF culture as the gold standard, but the correlation was too low to allow NP cultures to be recommended as a substitute for MEF culture. For epidemiology purposes, antibiotic susceptibility of MEF isolates can be predicted by NP culture results when samples are collected at onset of AOM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Acute otitis media (AOM) is one of the most common diseases in childhood and causes a considerable illness burden for children. Streptococcus pneumoniae (Spn), Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) and Moraxella catarrhalis (Mcat) are the 3 main pathogens causing AOM [1],[2]. The “gold-standard” for etiologic diagnosis of AOM is by detecting pathogens in middle ear fluid (MEF) by culture [1],[2]. However tympanocentesis is not routinely performed to obtain and culture MEF, so scientists and clinicians are in a conundrum regarding scant data to allow recommendations for treatment of AOM or sinusitis, leading to the suggestion that there may be no choice but to rely on nasopharyngeal cultures (NP) [3].

NP cultures have been used in the past as an epidemiologic tool to monitor the mix of otopathogens circulating in a country or region, and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern [4]. However, in a recent systematic review van Dongen et al [5] found that concordances between NP samples collected at onset of AOM compared to MEF isolates vary from 68% to 97% per microorganism. For the most prevalent microbes, positive predictive values were about 50%. Most negative predictive values were moderate to high, with a range from 68% up to 97%. The results indicate that NP samples do not provide an accurate proxy for those of middle ear fluid.

In 2006, we began a longitudinal, multi-year, prospective study of AOM with a primary objective to further understand the immunologic mechanisms responsible for the otitis prone children. During the course of our studies, we collected NP samples and MEF from these children. We have periodically reported one microbiologic aspects of our research [6]-[15]. Here we sought to answer several questions regarding the value of NP cultures as to their concordance with MEF cultures collected by tympanocentesis. Can NP samples taken during healthy visits serve as a surrogate for MEF cultures? In the current pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era, where otopathogen mix has changed due to vaccine efficacy, are NP cultures taken at onset of AOM concordant with MEF cultures? Can antibiotic susceptibility of otopathogens collected from the MEF be predicted by otopathogen isolates obtained from the NP at healthy or at onset of AOM visits?

Methods

Study population

The details of the study design have been previously described [16]. Study participants were recruited mainly from a single private pediatric office (Legacy Pediatrics) in Rochester, NY. Four other private pediatric groups joined in the recruitment effort by referral of patients to Legacy Pediatrics. Written informed parental consent was obtained prior to any study procedures. This study was approved by the University of Rochester IRB and subsequently by the Rochester General Hospital IRB.

Eligibility

Children were enrolled into the study at the age of 6 months and prospectively followed until 30-36 months of age (recently extended to 60 months of age). Inclusion criteria were: healthy, full term birth, no craniofacial anomalies and no known immune deficits. Participants were required to receive all doses of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV) according to the U.S. schedule; either PCV7 or PCV13 depending on the date of their enrollment. This is an ongoing prospective study where not all the children have completed the planned visits. In addition, although we request collecting samples at 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24 and at 30-36 months of age, most parents don’t consent for all the seven collection visits, especially since a venipuncture occurs simultaneously with the NP samplings. There is no statistically definable pattern of missing data [16].

Sampling

Nasal wash (NW) and nasopharyngeal swab (NP) samples were collected over 7 years (June 2006 to August 2013), prospectively from healthy children at 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24 and 30-36 months of age. During visits with AOM, MEF was obtained and cultured (both or a single tympanocentesis procedure depending on whether the infection was bilateral or unilateral) along with NW and NP swabs. Diagnosis of AOM was performed by validated otoscopists when children with acute onset of symptoms consistent with AOM had tympanic membranes (TMs) that were: (1) bulging or full, and (2) a cloudy or purulent effusion was observed, or the TM was completely opacified, and (3) TM mobility was reduced or absent. Sampling procedures, microbiology processing and identification, and molecular testing for organism identification have been previously described [6],[8],[15]. The oxacillin sensitivity of S. pneumoniae isolates was determined using Taxo™ P Discs (Beckton, Dickinson). Most Spn were also tested for their penicillin antibiotic susceptibility along with other antibiotics using VITEK 2 Gram Positive Susceptibility Card-AST-GP68 (BioMerieux, Inc) with the VITEK2 systems as described previously [17]. Microbiology data gathered from NW and NP are collectively represented as NP culture results. The detection rate of otopathogens from NW is higher than NP samples as shown recently by our group [18].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism. Positive cultures for Spn, NTHi or Mcat from a MEF samples were defined as the gold standard for the etiologic diagnosis of AOM. In this analysis, 2 MEF samples obtained at the same visit were regarded as one case of AOM and any otopathogen found in either or both of these samples was treated as a single finding in that case. The NW and NP swab results (hereafter referred to as NP cultures) and MEF culture results were compared with χ2 test. The positive predictive value (PPV) represents the proportion of NP samples that tested positive for a NTHi or Spn or Mcat, for which the paired MEF sample was also positive. The negative predictive value (NPV) represents the proportion of NP samples that tested negative for a common otopathogens, for which the paired MEF sample was also negative. The sensitivity represents the proportion of MEF samples that tested positive for NTHi or Spn or Mcat, for which the paired NP sample was also positive. The specificity represents the proportion of MEF samples that tested negative for NTHi or Spn or Mcat, for which the paired NP sample was also negative. Bacterial otopathogens between healthy vs AOM visits were compared using logistic regression with bacterial presence as binary outcome and visit type factor variable as predictor. A subject level random effect was included to model within-subject correlation. The function glmer() from the R package lme4 was used to calculate the model [19]. Estimates of the bacterial otopathogen presence rate and the visit group odds ratio were calculated directly from the model. The effects of age on the pathogens distribution during healthy colonization and AOM were assessed by Pearson correlation.

Results

Study population

During the 7-years involved in the current report 619 children were enrolled in the study. There were 2071 healthy visits among the children. The distribution of sample visits at 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24 and 30-36 months was as follows: 402 (19.4%), 388 (18.7%), 366 (17.7%), 297 (14.3%), 292 (14.1%), 244 (11.8%) and 82 (4%) respectively. A total of 530 AOM visits occurred in 309 children. The mean age of children at the time of AOM episode was 13.7 months and median age was 12.

Comparison of otopathogen mix during NP colonization at healthy and AOM visits

During healthy visits, Spn was isolated from 656 (31.7%) NP cultures compared to 253 (12.2%) for NTHi and 723 (34.9%) for Mcat alone or in combination (Table 1). At the onset of AOM, 256 (48.3%) of 530 NP samples were culture positive for Spn, 223 (42%) for NTHi and 251 (47.4%) for Mcat, alone or in combinations (Table 1). There was a significant difference (p < 0.0001) between healthy and at onset of AOM NP cultures. Data show that NTHi is more prevalent at AOM visits (Odd Ratio = 2.72). Co-colonization with multiple otopathogens distribution among healthy vs AOM visits are also shown in Table 1. The ratio of frequency of NTHi (AOM/healthy) is about 200% and this estimate does not depend on the co-pathogens. On the other hand, the ratio of frequency (AOM/healthy) of Mcat alone or Spn alone are about 50-60% (ie. less prevalent in AOM visits). For Spn-Mcat [no NTHi] the ratio of frequency (AOM/healthy) is about 100%, ie. equally prevalent. When Mcat or Spn is co-colonized with NTHi, there is an NTHi ratio of frequency of about 200% indicating NTHi seems to dominate. Otopathogens patterns change during the transition to AOM. For example, a Mcat-alone colonization is more likely to co-colonize during the transition to AOM than NTHi-alone colonization would be. This would explain the under-representation of Mcat-alone colonizations among AOM visits, without having to assume that Mcat-alone has a smaller transition rate to AOM. Co-colonization with multiple otopathogens was significantly higher (p < 0.0001) during AOM compared to healthy visits (Table 1). Staphylococcus aureus was also detected in 189 (9.1%) cases during healthy visits and 34 (6.4%) cases during AOM visits.

Correlation of MEF otopathogens during AOM with NP otopathogens isolated at healthy visits occurring within one month before AOM

In order to determine whether the presence of bacteria in NP samples obtained at healthy visits shortly prior to onset of AOM might be predictive of the etiology of AOM, we compared data from 81 AOM cases where NP samples were taken within one month before an AOM but not at onset of AOM. 31 (42%) of healthy NP colonized children had the same pathogen in the MEF during their AOM visit as they had at the healthy visit. We analyzed the correlation between concordance of MEF culture results and NP cultures taken at healthy visits 4, 3, 2, and 1 week prior to AOM onset. NP cultures taken 1 week prior to onset of AOM were more frequently concordant with MEF cultures compared to NP cultures taken 2 weeks prior to onset of AOM. As the time interval between NP culture sampling and onset of AOM lengthened the concordance became significantly lower (p < 0.05).

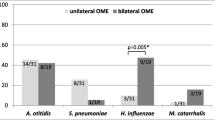

Correlation of MEF otopathogens with the NP at onset of AOM

To determine whether NP cultures correlated with MEF cultures at onset of AOM, 519 AOM cases out of 530 cases were compared. In 165 (31.8%) cases there was an exact match of MEF and NP isolate. In 359 (69.2%) cases at least one otopathogen in the NP sample matched the MEF culture result. In 160 (30.8%) cases no match was observed between the NP and MEF.

The otopathogens in the MEF where exact matches were observed in the NP (N = 165) is shown in Table 2. The best correlation was observed for NTHi (~37%). In 194 (37.3%) children there was partial agreement between the NP and MEF with 1 organism from the MEF found among 2 or 3 other otopathogens isolated from the NP. The predictive value of NP cultures according to otopathogen(s) in MEF is shown in Table 3.

Comparison of otopathogens with age

The presence of Spn, NTHi and Mcat in the NP (Figure 1A) and their presence in MEF during AOM (Figure 1B) were compared according to the age of the child. During healthy visits NP colonization by potential otopathogens significantly increased with age (p <0.05, with correlation r2 = 0.7880 for Spn, 0.931 for NTHi and 0.729 for Mcat). During AOM, the otopathogens in the MEF between 6-24 months of age did not show any age specific distribution. A negative trend with age was observed for Spn (p = 0.06 and r2 = 0.617) but NTHi and Mcat were uniformly distributed between 6-24 months of age.

Distribution of S. pneumoniae , NT Hi and M. catarrhalis bacteria at 6, 9, 12, 15, 18 and 24 months of age during healthy colonization and their presence in MEF during AOM. The healthy colonization of each bacteria increased significantly with age but no significant difference was observed with age during AOM. A negative trend with age was observed for S. pneumoniae in MEF during AOM shown by dotted line in the figure.

Antibiotic susceptibility of NP isolates at AOM compared to NP isolates at healthy visits

Recovery of Spn in the NP during healthy visits was not significantly different from recovery the NP during AOM visits. However, among NP cultures at healthy visits 187 (28.5%) of 656 Spn isolates were oxacillin resistant compared to 98 (38.3%) of 256 of NP cultures at onset of AOM (p = 0.004). The number of Spn detected during NP colonization with a MIC ≥2 μg/ml to penicillin at healthy visits was significantly lower 34 (6.7%) of 509 isolates compared to 205 Spn isolates at AOM visits (12.7%). Recovery of NTHi in the NP during healthy visits was significantly lower from the NP at onset of AOM (p < 0.0001). During healthy visits 57 (22.5%) of the 253 NTHi isolates were β-lactamase positive compared to 72(32.3%) at onset of AOM (p = 0.016). The frequency of recovery of Mcat in the NP during healthy visits was not significantly different from recovery in the NP during AOM visits and in almost all visits Mcat was β-lactamase positive.

Antibiotic susceptibility of middle ear fluid isolates compared to NP isolates at healthy visits

Oxacillin resistance of Spn in the MEF from AOM visits was not significantly different from Spn isolates at healthy visits. 42 (27.6%) of 152 Spn isolates from MEF at AOM visits were oxacillin resistant compared to 187 (28.5%) of 656 Spn isolates from NP at healthy visits. Comparison of Spn with MIC of ≥2 μg/ml to penicillin in MEF isolates and NP isolates at healthy visits showed 17.5% of 103 MEF isolates of Spn were penicillin-resistant compared to 6.7% of 509 NP isolates at healthy visits, which was significantly different (p = 0.001). 73 (37.2%) of 196 NTHi isolates from MEF at onset of AOM were β-lactamase positive compared to 57 (22.5%) of the 253 NTHi NP isolates during healthy visits (p = 0.001).

Antibiotic susceptibility of middle ear fluid isolates compared to NP isolates at onset of AOM

42 (27.6%) of 152 Spn isolates from MEF were oxacillin resistant. 98 (38.3%) of 256 isolates of Spn from the NP at onset of AOM were oxacillin resistant, significantly lower comparing MEF isolates with NP cultures at onset of AOM (p < 0.001). Comparison of Spn with MIC of ≥2 μg/ml to penicillin in MEF and NP isolates showed 17.5% of 103 MEF isolates of Spn were penicillin-resistant compared to 12.7% of NP isolates at onset of AOM, which was not significantly different (p = 0.612). 73 (37.2%) of 196 NTHi were β-lactamase positive. The proportion of β-lactamase positive in NTHi MEF cultures was not significantly different from NP cultures collected at onset of AOM (p = 0.287). To calculate whether antibiotic resistance of MEF pathogens can be predicted from NP isolates obtained at onset of AOM, we compared oxacillin resistance in 127 paired NP and MEF Spn isolates and found the PPV to be very high at 95.3%. Similarly comparison of β-lactamase activity of 170 paired isolates of NTHi showed the predictive value at 96%.

Discussion

Historically during the early 1970s to early 1990s, the relative proportion of otopathogens in MEF during AOM was 40% for S. pneumoniae, 25% for H. influenzae and 12% for M. cattarrhalis [20]. After the introduction of PCV-7 vaccine in the early 2000’s, changes in the frequency and distribution of AOM pathogens occurred [15],[17],[21],[22]. We sought to determine if NP cultures could be used to predict MEF cultures in the post PCV era. In this study from June 2006-August 2013, the relative proportion of otopathogens in MEF during AOM was 28.7% Spn, 37% NTHi and 19.6% Mcat. Thus our group and others have shown the introduction of PCV-7 and more recently PCV-13 has reduced the contribution of Spn causing AOM [15],[17],[22]-[24].

Can NP samples taken during healthy visits serve as a surrogate for MEF cultures? The results from the present study show that predicting the etiology of AOM in MEF cultures by analyzing NP cultures at healthy visits is poor and cannot be recommended as a substitute strategy for collection of MEF.

Are NP cultures taken at onset of AOM concordant with MEF cultures? NP cultures collected at onset of AOM to predict MEF culture results are somewhat better than NP cultures collected at healthy visits. The PPV for NP cultures at onset of AOM compared to MEF was 48.8% for Spn, 70.6% for NTHi and 36.9% for Mcat. NPV values for all the pathogens were high.

Can antibiotic susceptibility of otopathogens collected from the MEF be predicted by otopathogen isolates obtained from the NP at healthy or at onset of AOM visits? Our data show poor correlation in predicting the antibiotic resistance of microorganisms in the MEF compared to NP samples taken during healthy visits. In comparison we found antibiotic susceptibility of otopathogens collected from the MEF can be predicted by otopathogen isolates obtained from the NP at onset of AOM visits.

We postulated and found that the correlation of NP otopathogens isolated at healthy visits occurring within one month before AOM would be stronger than cultures taken at times further distant from onset of AOM. The results are consistent with prior work showing that typical pathogenesis of AOM involves recent (generally < 2 weeks) acquisition of a potential otopathogen progressing to cause the infection [25],[26].

We observed that Spn and NTHi NP colonization increased significantly between 6 and 30-36 months of age, but as children got older the relationship between detection of a potential otopathogen in the NP with detection in MEF got weaker. Our results are in agreement with Syrjanen et al [27] who also found a high prevalence of NP colonization but low frequency of Spn as an etiology of AOM with age, especially after children became >18 months of age. However, neither our results nor those of Syrjanen et al [27] allow confidence to use NP cultures as surrogates of MEF cultures in children below 2 years of age. Our results are consistent and also support a Finnish study by Kilpi et al [28] where they showed that the incidence of Spn AOM peaked at 12 months of age, whereas the incidence of NTHi AOM peaked later at 20 months of age.

Our study has potential limitations. Our results were obtained from a single community and mostly from a single private pediatric practice. However, we have compared our MEF culture results in the past to those of Bardstown KT [29],[30], Pittsburgh PA [31] and Fairfax VA [32],[33] where tympanocentesis has been performed and found results to be similar [22]. Also, while participating in multicenter trials of new antimicrobial agents and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines during the 1990s and 2000s, our center had MEF culture results similar to multiple other U.S. centers but not to centers outside the U.S. where tympanocentesis was performed [34]-[37].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the overall results bring into question the epidemiologic value of NP cultures to predict otopathogen mix or anticipated antibiotic susceptibility patterns among otopathogens. The results published here extend and confirm those of another recent paper from our group [17] in showing that NP isolation of otopathogens at onset of AOM better reflect, albeit incompletely, likely MEF isolates compared with NP isolates at times of health. We will continue to collect MEF at our otitis media research center for the coming years and collect NP cultures in order to provide results to the health care community for review and consideration in recommendations for AOM management.

References

Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2004, 113 (5): 1451-1465. 10.1542/peds.113.5.1451.

Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA, Joffe MD, Miller DT, Rosenfeld RM, Sevilla XD, Schwartz RH, Thomas PA, Tunkel DE: The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013, 131 (3): e964-e999. 10.1542/peds.2012-3488.

Wald ER, DeMuri GP: Commentary: antibiotic recommendations for acute otitis media and acute bacterial sinusitis in 2013–the conundrum. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013, 32 (6): 641-643. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3182868cc8.

Schwartz R, Rodriguez WJ, Mann R, Khan W, Ross S: The nasopharyngeal culture in acute otitis media: a reappraisal of its usefulness. J Am Med Assoc. 1979, 241 (20): 2170-2173. 10.1001/jama.1979.03290460034016.

van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, van Zon A, Bogaert D, Sanders EA, Schilder AG: Evaluation of concordance between the microorganisms detected in the nasopharynx and middle ear of children with otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013, 32 (5): 549-552. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318280ab45.

Kaur R, Adlowitz DG, Casey JR, Zeng M, Pichichero ME: Simultaneous assay for four bacterial species including Alloiococcus otitidis using multiplex-PCR in children with culture negative acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010, 29 (8): 741-745. 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181d9e639.

Kaur R, Casey JR, Pichichero ME: Relationship with original pathogen in recurrence of acute otitis media after completion of amoxicillin/clavulanate: bacterial relapse or new pathogen. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013, 32 (11): 1159-1162. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31829e3779.

Kaur R, Chang A, Xu Q, Casey JR, Pichichero ME: Phylogenetic relatedness and diversity of non-typable Haemophilus influenzae in the nasopharynx and middle ear fluid of children with acute otitis media. J Med Microbiol. 2011, 60 (Pt 12): 1841-1848. 10.1099/jmm.0.034041-0.

Friedel V, Chang A, Wills J, Vargas R, Xu Q, Pichichero ME: Impact of respiratory viral infections on alpha-hemolytic streptococci and otopathogens in the nasopharynx of young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013, 32 (1): 27-31. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31826f6144.

Pichichero ME, Casey JR: Evolving microbiology and molecular epidemiology of acute otitis media in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007, 26 (10 Suppl): S12-S16. 10.1097/INF.0b013e318154b25d.

Xu Q, Kaur R, Casey JR, Adlowitz DG, Pichichero ME, Zeng M: Identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae in culture-negative middle ear fluids from children with acute otitis media by combination of multiplex PCR and multi-locus sequencing typing. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2011, 75 (2): 239-244. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.11.008.

Xu Q, Kaur R, Casey JR, Sabharwal V, Pelton S, Pichichero ME: Nontypeable Streptococcus pneumoniae as an otopathogen. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011, 69 (2): 200-204. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.09.019.

Xu Q, Almudervar A, Casey JR, Pichichero ME: Nasopharyngeal bacterial interactions in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012, 18 (11): 1738-1745. 10.3201/eid1811.111904.

Xu Q, Casey JR, Chang A, Pichichero ME: When co-colonizing the nasopharynx haemophilus influenzae predominates over Streptococcus pneumoniae except serotype 19A strains to cause acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012, 31 (6): 638-640. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31824ba6f7.

Casey JR, Adlowitz DG, Pichichero ME: New patterns in the otopathogens causing acute otitis media six to eight years after introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010, 29 (4): 304-309.

Friedel V, Zilora S, Bogaard D, Casey JR, Pichichero ME: Five-year prospective study of paediatric acute otitis media in Rochester, NY: modelling analysis of the risk of pneumococcal colonization in the nasopharynx and infection. Epidemiol Infect. 2014, 142 (10): 2186-2194. 10.1017/S0950268813003178.

Casey JR, Kaur R, Friedel VC, Pichichero ME: Acute otitis media otopathogens during 2008 to 2010 in Rochester, New York. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013, 32 (8): 805-809.

Kaur R, Pichichero M: Nasopharyngeal wash versus swab specimens for culture of nontypeable haemophilus influenzae and other respiratory bacterial pathogens. J Infect Dis. 2014, 210 (10): 1684-1685. 10.1093/infdis/jiu309.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S: lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R package version 1.1-6. 2014, ., [http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4]

Bluestone CD, Stephenson JS, Martin LM: Ten-year review of otitis media pathogens. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992, 11 (8 Suppl): S7-S11. 10.1097/00006454-199208001-00002.

Casey JR, Pichichero ME: Changes in frequency and pathogens causing acute otitis media in 1995-2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004, 23 (9): 824-828. 10.1097/01.inf.0000136871.51792.19.

Pichichero ME, Casey JR, Hoberman A, Schwartz R: Pathogens causing recurrent and difficult-to-treat acute otitis media, 2003-2006. Clin Pediatr. 2008, 47 (9): 901-906. 10.1177/0009922808319966.

Gounder PP, Bruce MG, Bruden DJ, Singleton RJ, Rudolph K, Hurlburt DA, Hennessy TW, Wenger J: Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on nasopharyngeal colonization by streptococcus pneumoniae – Alaska, 2008–2012. J Infect Dis. 2013, 209 (8): 1251-1258. 10.1093/infdis/jit642.

Caeymaex L, Varon E, Levy C, Bechet S, Derkx V, Desvignes V, Doit C, Cohen R: Characteristics and Outcomes of Acute Otitis Media in Children Carrying Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae in Their Nasopharynx as a Single Otopathogen after Introduction of the Heptavalent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014, 33 (5): 533-536. 10.1097/INF.0000000000000213.

Syrjanen RK, Auranen KJ, Leino TM, Kilpi TM, Makela PH: Pneumococcal acute otitis media in relation to pneumococcal nasopharyngeal carriage. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005, 24 (9): 801-806. 10.1097/01.inf.0000178072.83531.4f.

Labout JA, Duijts L, Lebon A, de Groot R, Hofman A, Jaddoe VV, Verbrugh HA, Hermans PW, Moll HA: Risk factors for otitis media in children with special emphasis on the role of colonization with bacterial airway pathogens: the Generation R study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011, 26 (1): 61-66. 10.1007/s10654-010-9500-2.

Syrjanen RK, Herva EE, Makela PH, Puhakka HJ, Auranen KJ, Takala AK, Kilpi TM: The value of nasopharyngeal culture in predicting the etiology of acute otitis media in children less than two years of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006, 25 (11): 1032-1036. 10.1097/01.inf.0000241097.37428.1d.

Kilpi T, Herva E, Kaijalainen T, Syrjanen R, Takala AK: Bacteriology of acute otitis media in a cohort of Finnish children followed for the first two years of life. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001, 20 (7): 654-662. 10.1097/00006454-200107000-00004.

Block SL, Hedrick JA, Kratzer J, Nemeth MA, Tack KJ: Five-day twice daily cefdinir therapy for acute otitis media: microbiologic and clinical efficacy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000, 19 (12 Suppl): S153-S158. 10.1097/00006454-200012001-00004.

Block SL, McCarty JM, Hedrick JA, Nemeth MA, Keyserling CH, Tack KJ: Comparative safety and efficacy of cefdinir vs amoxicillin/clavulanate for treatment of suppurative acute otitis media in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000, 19 (12 Suppl): S159-S165. 10.1097/00006454-200012001-00005.

Aspin MM, Hoberman A, McCarty J, McLinn SE, Aronoff S, Lang DJ, Arrieta A: Comparative study of the safety and efficacy of clarithromycin and amoxicillin-clavulanate in the treatment of acute otitis media in children. J Pediatr. 1994, 125 (1): 136-141. 10.1016/S0022-3476(94)70140-7.

Pelton SI, Teele DW, Shurin PA, Klein JO: Disparate cultures of middle ear fluids: results from children with bilateral otitis media. Am J Dis Child. 1980, 134 (10): 951-953. 10.1001/archpedi.1980.02130220029009.

Teele DW, Pelton SI, Klein JO: Bacteriology of acute otitis media unresponsive to initial antimicrobial therapy. J Pediatr. 1981, 98 (4): 537-539. 10.1016/S0022-3476(81)80755-X.

Pichichero M: Widening differences in acute otitis media study populations. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 49 (11): 1648-1649. 10.1086/647934.

Arguedas A, Dagan R, Leibovitz E, Hoberman A, Pichichero M, Paris M: A multicenter, open label, double tympanocentesis study of high dose cefdinir in children with acute otitis media at high risk of persistent or recurrent infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006, 25 (3): 211-218. 10.1097/01.inf.0000202138.12950.3c.

Arguedas A, Dagan R, Pichichero M, Leibovitz E, Blumer J, McNeeley DF, Melkote R, Noel GJ: An open-label, double tympanocentesis study of levofloxacin therapy in children with, or at high risk for, recurrent or persistent acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006, 25 (12): 1102-1109. 10.1097/01.inf.0000246828.13834.f9.

Pichichero ME, Casey JR: Comparison of study designs for acute otitis media trials. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008, 72 (6): 737-750. 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.02.020.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by NIH NIDCD RO1 08671. We thank the nurses and staff of Legacy Pediatrics and the collaborating pediatricians from Sunrise Pediatrics, Westfall Pediatrics, Lewis Pediatrics and Long Pond Pediatrics, the parents who consented and the children who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RK and MEP contributed to study design, interpretation of data and writing. KZ contributed to data collection and data analyses. JC contributed to clinical management of patients and critical review of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript during preparation and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaur, R., Czup, K., Casey, J.R. et al. Correlation of nasopharyngeal cultures prior to and at onset of acute otitis media with middle ear fluid cultures. BMC Infect Dis 14, 640 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0640-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0640-y