Abstract

Objectives

To clarify the mechanisms of interventions addressing loneliness and social isolation in older adults living in nursing homes through the involvement of primary and secondary informal caregivers.

Methods

This scoping review was performed by two independent reviewers, covering the period between 2011 and 2022 and the databases MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Scopus. It included terms related to (A) informal caregivers, (B) nursing homes, (C) psychosocial interventions, (D) involvement and (E) social isolation or loneliness.

Results

Thirty-three studies met the inclusion criteria. Although there were various definitions and assessment tools related to social isolation and loneliness, the studies referred to three dimensions of these concepts in nursing home residents: the quantity of social interactions, the perception of these encounters and biographical changes in social relationships. Most studies did not explicate the mechanisms of these interventions. The review uncovered the following aspects of intervention mechanisms: increasing opportunities for social contact, creating meaningful encounters, maintaining existing relationships with primary informal caregivers and establishing new ones with secondary informal caregivers.

Conclusion

Studies reporting on interventions addressing loneliness and social isolation in nursing home residents need to clarify and detail their intervention mechanisms in order to foster more targeted interventions. In addition, there is a need for further research on large-scale programs or care philosophies in this field and the development of intervention designs, which allow for tailored intervention formats in order to respond to the individual perception of social relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Loneliness and social isolation are mayor challenges in geriatric care. For the population over 80 years of age it is estimated the prevalence rate of loneliness lies between 27.1% for severe and 32.1% for moderate cases, while it is at 33.6% for social isolation [1]. It is estimated the mean prevalence of loneliness in nursing home residents is 61% for moderate and 35% for severe levels [2]. These alarming overall tendencies were highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath [3,4,5,6]. The health effects of loneliness and social isolation further underline the concern: Both states are generally linked to increased mortality [7]. In addition, studies on older adults living in long-term care settings report that loneliness increases the risk for depression, suicidal ideation and frailty [8]. There are various risk factors for social isolation in nursing homes: reaching from individual health related communication barriers to systemic issues, such as the location of many facilities, and structural challenges including socioeconomic disadvantages or discriminatory public perceptions [9].

Frequently social isolation is defined as the ‘objective’ number of social interactions, while loneliness characterizes the ‘subjective’ evaluation of these interactions [10]. However, there is considerable variation in how both concepts are defined and operationalized [11,12,13]. Thus the term social isolation touches upon various aspects of the number of social contacts and subjective evaluations of these encounters [12]. Similarly each definition of loneliness emphasizes a specific aspects of the phenomenon, for example highlighting the cognitive evaluation of the actual and desired relationships or the experience of a situation as lacking social relationships [13]. Robert Weiss’ seminal work on loneliness distinguishes between emotional and social loneliness – the former referring to the lack of intimate relationships while the latter describes the feeling of missing a social network [14]. Building on this distinction a recent conceptual review on loneliness in adults differentiates between three dimensions of loneliness: the social dimension of loneliness highlights social connections and the feeling being socially isolated, the emotional dimension touches upon the quality of relationships, and the existential dimension of loneliness captures the feeling of being fundamentally (and not only temporarily) separated from others [15].

For older adults living in nursing homes, functional relationships with staff alone may not compensate for loneliness and social isolation. Contrary to community dwelling older adults, nursing home residents can potentially profit from the company other residents [16]. A crucial aspect for nursing home residents is support from family members and friends [17, 18]. In addition, older adults living in nursing homes can receive support from a range of external community actors, voluntary workers or institutions like schools and associations, providing various forms of informal care and companionship. Though most of the literature refers to informal caregivers as family members or friends, there are concurring understandings of the term [19]. In the context of nursing homes, we distinguish two main groups: primary informal caregivers who have a biographical relationship with one nursing home resident (e.g. relatives, friends) and secondary informal caregivers who have a connection to the nursing home itself (e.g. schoolchildren, members of associations, voluntary workers). Secondary caregivers play a robust role in expanding the circle of social contacts for residents [20,21,22] and opening the nursing home to the larger community. The inclusion of these groups in the nursing home is a complex process [23] involving informal caregivers’ access to everyday activities and active engagement in decision-making and the care process.

There are various psychosocial interventions addressing the involvement of primary and secondary informal caregivers in nursing homes, these interventions change the behaviour of these actors with the aim to advance or retain the mental or physical health and well-being of residents. However, the facilitation of this involvement remains underexplored [24]. There are increasing calls for refining and tailoring interventions against loneliness and social isolation for individuals and specific groups of older adults [10, 25]. Previous reviews on interventions against loneliness highlight the specificity of interventions for older adults in general [26, 27] or nursing home residents in particular [28, 29], we add to this debate by looking at a sub-set of these interventions – interventions involving informal caregivers into the facility. This review therefore explores the field of intervention studies addressing loneliness and social isolation through the involvement of both groups of informal caregivers in nursing homes. It aims to (A) clarify how intervention studies employ the concepts of loneliness and social isolation and (B) subsequently lay out the mechanisms through which interventions address the dimensions of loneliness and social isolation. Mechanisms describe how an intervention brings about a change in a certain outcome [30]. The review hence contributes to the endeavour to broaden theoretical understandings of how interventions contribute to reducing loneliness and social isolation [10, 27].

Methods

As the review explored the broad extent of the knowledge on intervention mechanisms against loneliness and social isolation, we chose a scoping review methodology and based our review on the criteria of the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis [31]. We used a modified version of the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and published a protocol for the review (https://osf.io/vjzqw/). With regard to this protocol, the search had to be limited to empirical studies and conceptual papers to better reconstruct the intervention mechanisms themselves.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies on psychosocial interventions against loneliness and social isolation. The term psychosocial interventions refers to a wide array of activities aimed at maintaining or improving the functioning, well-being and social relationships of older adults [32]. These interventions focused on the involvement of primary and secondary informal caregivers in the facility life of nursing homes, i.e., institutions providing 24-hour support to people requiring assistance during (instrumental) activities of daily living due to identified health needs [33]. Studies comparing nursing homes with hospital or community settings were also included. Hence, the populations covered in this review included nursing home staff, primary and secondary informal caregivers and residents of nursing homes, with a focus on primary informal caregivers such as partners, relatives and friends and secondary informal caregivers, i.e. broader community actors engaging with the nursing home. For our review, we define primary informal caregivers as people who feel a sense of belonging towards a certain person within the nursing home and maintain a biographical relationship. Secondary informal caregivers are defined as people that feel a sense of belonging towards the nursing home itself. Studies on nursing home residents alone were included only if the residents were explicitly addressed by the interventions as providers of support to their peers as secondary informal caregivers.

As it was the aim to explore the field of studies, the review covered peer-reviewed articles as well as grey literature, incorporated studies with qualitative as well as quantitative designs regardless of their quality. We excluded letters to the editor, posters, review articles and commentaries and included empirical intervention studies and conceptual papers on interventions in English and German published between 2011 and 2022. Focussing the sample on empirical intervention studies and conceptual papers allowed us to pinpoint the outcomes of these interventions as well as their mechanisms.

Search strategy

We carried out a preliminary search in MEDLINE and a manual search in PROSPERO to refine the search terms. The search in April 2021 and an update in December 2022 included the following information sources: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Scopus. The search strategy comprised terms related to (A) informal caregivers, (B) nursing homes, (C) psychosocial interventions, (D) involvement and (E) social isolation or loneliness (Table 1). We hand-searched for additional relevant sources in the bibliographies of articles included in the full-text screening and carried out a forward citation of these articles in Google Scholar.

Selection process

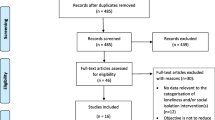

We gathered the included titles found in different information sources in EndNote 20 (Clarivate Analytics) and removed duplicates from the list (Fig. 1). Afterwards, we screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles for their eligibility according to the five inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers (AH and DA) screened and selected articles and carried out the data extraction, and a third reviewer was consulted in case of divergences (MH).

Data extraction and analysis

Based on the JBI criteria for data extraction in scoping reviews, we used an extraction sheet with information on the country of intervention, methodology, population included, sample size and type of care facility; a detailed description of the intervention; the definition, use and/or measurement of the concepts loneliness and social isolation and the challenges and facilitators mentioned in the studies; and a bibliographical note.

We started by comparing the definitions, assessments and implicit uses of loneliness and social isolation across articles based on the extraction sheets. Subsequently, we employed these dimensions to the intervention descriptions in order to highlight the implicit intervention mechanisms. In order to clarify the mechanisms of these interventions, we furthermore assessed the description of the mechanism and interpreted included studies with regard to the type of relationship (establish/maintain relationships, meaningful connections) and involvement (group, dyad) they generated.

Results

As a result of the database search, a total of 1,013 articles were retained (Fig. 1). After removing 332 duplicates, we screened the title and abstract of the remaining 681 articles and added six sources through backward and forward citation. We performed a full-article screening of 59 articles, of which 26 were excluded for various reasons (see Fig. 1), leading to 33 articles included in the review (Table 2).

Study characteristics

The articles reported on interventions conducted in Canada (n = 11), the United Kingdom (n = 6), Australia (n = 5), the United States (n = 5), Taiwan (n = 2) and Germany (n = 1), with two studies not clarifying the country. Most texts were published between 2020 and 2022 (n = 22), while publications during the previous periods between 2011 and 2013 (n = 4), 2014 and 2016 (n = 2) as well as 2017 and 2019 (n = 5) remained relatively stable. Most studies employ a qualitative design (n = 12), while slightly fewer chose a mixed-method approach (n = 8). A smaller number of articles used a quantitative design (n = 5), did not clarify the data collection approach (n = 3) or did not gather empirical data at all (n = 5). Articles not based on empirical data included study protocols and concept proposals.

Residents were the main target group of all interventions, i.e. the interventions aimed at mitigating loneliness and social isolation in residents. Some interventions focused on residents with cognitive impairment only (n = 5), while most targeted older adults living in nursing homes in general (n = 28).

Most studies reported on interventions that introduced a digital technology or that trained a population in the usage of a digital technology (n = 17). Such interventions consisted of videoconferencing tools delivered through smartphones, computers, televisions or robots [34,35,36,37,38,39,40]; other communication technology, such as messaging apps, online platforms or e-mail programs [41,42,43,44,45,46]; or the technological delivery of entertainment activities or therapeutic support, i.e., video gaming and digital reminiscence tools [47,48,49] or a combination of various modified tablet functions [50].

Other studies reported introducing therapeutic or leisure activities into nursing homes (n = 11), such as music- and art-based activities [51,52,53,54,55], intergenerational visiting programmes [56,57,58] and peer-mentoring [59,60,61]. The remaining articles described changes in the management, living arrangements and philosophy of care at nursing homes (n = 5), including a multi-componential strategy [62], a plan on how to design and execute an integrated intervention [63], the Eden Alternative programme [64] and reports on intergenerational living arrangements [65, 66].

Definition and measurement of loneliness and social isolation

Most texts only loosely referred to the concepts of loneliness and social isolation (n = 13); i.e., they did not define one or both concepts or systematically assess them as outcomes. A majority of studies does not report on loneliness or social isolation as an outcome (n = 16). The UCLA Loneliness Scale [67,68,69] was the most frequently used assessment tool for loneliness, but was used in different versions, while the de Jong–Gierveld Loneliness Scale [70] was only sporadically found. Only two studies reported on loneliness with qualitative interviews. The studies measured social isolation with the Duke Social Support Index [71], the Social Support Behaviours Scale [36] and the Friendship Scale [72].

In general, the term loneliness was used more frequently than social isolation. Most studies employ both terms (n = 19), while fewer use loneliness (n = 10) and only a fraction refer to social isolation (n = 4). There was a lack of consistency in how the two concepts were defined and, subsequently, how they were distinguished from each other. Instead, the articles revealed various interlinked concepts.

Although the articles did not unilaterally share a definition of loneliness and/or social isolation, in discussing these concepts, they mainly touched upon three dimensions. First, they referred to the quantity of social interactions. Thus, social isolation was seen as the objective lack of interactions [51], referring to the number of social contacts and interactions [53] or criticizing the lack of opportunities for nursing home residents to interact with each other or external actors [65]. The second dimension concerns the subjective perspective on interactions: Several studies claimed that loneliness occurs when individuals do not consider their existing interactions to be meaningful and fulfilling. For instance, two studies defined social connectedness as the existence of meaningful social interactions [41, 42]. This dimension includes the definition of loneliness as a misfit between the desired and the actual number of social interactions, i.e., the involuntary state of social isolation [44]. The third dimension sheds light on the biographical changes in social relationships and, subsequently, the distinction of primary and secondary informal caregivers. The studies hence argued that loneliness occurs when existing social relationships dissolve or when individuals find themselves incapable of establishing new social ties. The conceptual texts referred to the loss of social ties in older adults living in nursing homes in general [63] or specifically to the loss of friends and family members [62].

Intervention mechanisms

Most studies did not sufficiently lay out the mechanism of the intervention. A large amount of studies did not explicitly mention how the intervention brings about reduced loneliness and/or social isolation (n = 12). In addition, in most cases the description of the mechanism was reduced to a singular sentence and did not give details about the interaction of elements of an intervention with these mechanisms. Comparing the interventions based on the three dimensions of loneliness and social isolation – the quantity of social interactions, the perception of these interactions and the biographical changes in social relationships – highlights three aspects of intervention mechanisms. These are not mutually exclusive and occur in various combinations in these studies.

The first aspect of intervention mechanisms is creating opportunities for social contact. Thus, the technologies, activities or large-scale changes in management were designed to decrease loneliness and social isolation by means of introducing or increasing encounters with informal caregivers. Several studies offered opportunities for interaction or connections (n = 8) or facilitated communication (n = 6). With regard to the quantity of interactions, the studies converged in establishing opportunities for increased encounters but diverged on how much time participants spent with others and how many actors were involved during the intervention. For example, one intervention involved 30 min of exchange per week [46], whereas another intervention involved 30 h of activities per month [66]. The way informal caregivers were involved also differed: The sample includes interventions involving informal caregivers in group activities as well as dyadic (i.e. person-to-person) encounters. There are interventions combining group and dyadic elements (n = 12), dyadic interventions (n = 10) and group interventions (n = 9).

The second aspect of ways to decrease loneliness and social isolation consists in creating meaningful connections. With regard to this, studies did not only increase or introduce contacts, the intervention was designed to foster meaningful exchange with informal caregivers. Several interventions were rooted in reflection on meaningful activities (n = 4) or concluded that an encounter is meaningful based on a proxy such as spontaneous activities, shared goals of participants or the length of interactions [42, 65]. However, the studies did not point out how tailored forms and durations of interactions were provided during the intervention to cater to the individual perceptions of the participants, which went beyond simple nonparticipation. One conceptual text therefore suggested that strategies to combat loneliness should include assessing loneliness scores, encouraging nursing staff to continuously monitor the quality of social interactions and designing a customized plan together with each resident [63].

Finally, the third aspect of intervention mechanisms consists in either establishing or maintaining social relationships. This aspect focusses on the informal caregivers involved and pinpoints the heterogeneity of people involved in nursing homes. For primary informal caregivers, the group most frequently addressed by these interventions was relatives (n = 12). In comparison, fewer studies mentioned friends (n = 2). For secondary informal caregivers, there were several intergenerational interventions involving children and their parents, schoolchildren and university students (n = 8) and interventions that addressed the potential of older adults and, in particular, other residents as informal caregivers (n = 8).

Most interventions either maintained contact with primary caregivers or created new social relationships with secondary caregivers, and only a few studies combined both aspects. In one intervention, trained student volunteers offered technical assistance to residents in sending emails to family members [45], a second intervention combined a customized tablet interface for families with a virtual stakeholder forum [50] and a third intervention displayed photographs uploaded by family members which could be seen by other residents and were to foster exchange between them [49]. The Eden Alternative established regular ties with children and other residents while also encouraging meaningful family connections [64], and another program encouraged peer support and the maintenance of contact with friends and family [62].

The interventions created opportunities for new groups to become involved in nursing homes. Visits included regular phone calls with university students [46] and video calls with schoolchildren [40]. Furthermore, a peer-mentoring programme arranged visits between community and resident mentors and cognitively impaired resident mentees [59,60,61]. Three studies described interventions establishing leisure activities, such as seasonal activities with university students [56], gardening, food preparation and related social events with schoolchildren [57]. There were several interventions that introduced games: an open playgroup with nursing home residents, younger children and their parents [58]; online quiz sessions [39]; and exergaming [47] with residents. Music-based interventions ranged from choir visits [54] to interactive music sessions with music experts [55] and multicomponent music approaches [51, 53]. Two studies evaluated intergenerational living arrangements, where students moved into a nursing home for a certain amount of time and fulfilled tasks for residents [65, 66].

Fewer interventions focused on maintaining existing relationships, and all of these interventions relied on digital technology. Videoconferencing was used to allow digital visits with friends and family members [36, 37], which were facilitated by a wheeled device [38] or a telepresence robot [34, 35]. Some interventions combined videoconferencing with asynchronous or text-based communication technologies. Examples include a multipurpose software using video, audio and picture content [41, 42]; and a platform combining video calls, voice-mail and text messaging [43]. There were online communication interventions [44] and, in particular, digital reminiscence applications that allowed primary informal caregivers to upload photos, music, books and video clips to a private device [48] or provide pictures that would automatically pop up on a public screen in the nursing home [49].

Discussion

The review shows the breadth of interventions addressing loneliness and social isolation by involving different groups of informal caregivers in nursing homes. However, these studies rarely described explicitly how the intervention influenced or aimed at influencing loneliness and social isolation. Thus, as also pointed out in the latest update of the Medical Research Councils guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions [30], there is a need for future intervention studies to give detailed descriptions on the mechanisms underlying interventions.

Only a limited amount of studies focused on residents with cognitive impairment and previous reviews have concluded that studies on interventions against loneliness and social isolation often exclude them [3, 29, 73]. Although there are already approaches to the inclusion of family members of residents with cognitive impairment [74], there is a need for further research on how these interventions can address loneliness and social isolation. Such interventions can profit from first in-depth insights on how these residents perceive loneliness [75].

Three dimensions of loneliness and social isolation

The review revealed a plurality of assessment tools for and definitions of loneliness and social isolation in intervention studies. Several studies used the UCLA Loneliness Scale to report on loneliness scores – a trend emphasized in other reviews [3, 28, 29] – whereas there was no dominant assessment tool used to measure social isolation. In addition, other reviews have also highlighted the lack of coherence in defining these terms in intervention studies [5, 25]. As the studies did not provide such an explicit coherent use of definitions and measurements, we compared the definitions, measurements and implicit uses of loneliness and social isolation and thus highlighted three distinct dimensions in which the studies employed these concepts: the quantity of social interactions, the perception of these interactions and biographical changes in social relationships.

Analysing the quantitative dimension of loneliness and social isolation revealed that the most interventions converged in offering opportunities for social interactions, but covered different time frames and group sizes. The dimension of individual perception of social interactions corresponds to the cognitive theory of loneliness by Letitia Anne Peplau and Daniel Perlman defining loneliness as a discrepancy between actual and desired relationships [76]. Considering this dimension of loneliness in interventions goes beyond changing the amount of social contacts and highlights the need to assess the desired relationships of study participants. Although the studies all mentioned the perception of social relationships, this was not systematically evaluated during the delivery of the interventions. It is therefore not possible to deduce from the results of the studies which attributes of social relationships have an effect on social isolation and loneliness. Studies show, for example, that evenings and weekends are experienced as particularly lonely or that types of relationships play an important role and the meaning of loneliness for people is highly individual [75, 77]. Future studies should explicitly describe and evaluate these influencing elements.

Robert Weiss’s distinction between social loneliness, the absence of intimate relationships, and emotional loneliness, the lack of an overall sense of connectedness, captures the difference between maintaining the ties with primary informal caregivers and establishing new social relationships with secondary informal caregivers. Analysing the studies on the dimension of biographical changes in social relationships showed that informal caregivers are a heterogeneous group consisting of relatives and friends with established relationships with nursing homes residents as well as newly formed contacts spanning different age groups and organizational backgrounds such as schools, universities, or other nursing homes. Overall, the studies differed regarding the question which informal caregivers are most important for combatting loneliness and social isolation in nursing home residents. Other studies mainly point towards the role of family relationships in general [18] and the support of adult children in particular [17]. Some of the included studies targeted residents themselves as informal caregivers to their peers. Common activities between residents might increase overall social interactions [78]. Residents might especially be able to provide company and peer support to each if engaged in meaningful collective activities [16, 79]. Working with the distinction of social and emotional loneliness can especially shed light on the mechanisms of those interventions which combine meaningful activities with the creation of new social relationships [59,60,61].

The mechanisms of interventions alleviating loneliness and social isolation

There is an overall need for studies to clarify the mechanisms through which interventions involving informal caregivers decrease levels of loneliness and social isolation, as pointed out for the case of befriending programmes [80]. The review highlighted three main aspects of the mechanisms through which interventions involving informal caregivers in nursing homes target loneliness and social isolation: Increasing social interactions, assuring meaningful and desired relationships and establishing new or maintaining existing relationships. Studies thus have to show, how an intervention sparks social interaction, how it ensures that these interactions are meaningful for and desired by the individuals participating in the implementation and how it relates to the biography of the target group.

The interventions included in this review ranged from short-term visits, to recurring weekly activities, to long-term live-in arrangements, and they included large groups as well as individual meetings. Earlier reviews classified interventions against loneliness, among other things, as person-to-person or group interventions [26, 27, 73, 81] and noted that in nursing homes, group interventions are more common than one-on-one approaches [73]. The review showed that interventions involving informal caregivers equally created group and dyadic settings or even combined both forms with each other.

Several interventions in this sample revolved around the questions of meaningful or purposeful activity, a tendency also highlighted in another review [26]. Although the studies emphasized individual perceptions of and needs for social interactions, they did not establish how they considered this aspect during the delivery of the interventions. There is first evidence on the impact of person-centred care on loneliness among nursing home residents [29] and the aspects of meaningful engagement [16, 82]. Therefore, there is a need to further consider multiple ways of participating in a single intervention and modes for adjusting the implementation to individual needs.

Interventions focus on maintaining social relationships established prior to residents moving into a nursing home or creating opportunities for new encounters for residents. While a review on interventions against loneliness in older adults reported on a dominance of approaches maintaining social relationships [26], both kinds of mechanisms are covered by intervention studies in this sample. However, it is possible that interventions establishing or maintaining social relationships might use different components for similar interventions. For example, it is unclear if a videoconferencing with family members and strangers needs the same or different supporting documents such as conversation aids.

Limitations

The articles covered a limited geographical area, with many studies from Canada. In addition, the review was limited to recent articles, and thus, certain interventions – especially technological innovations – might have been overrepresented. Although the review covered a wide array of interventions, there are other interventions that might have the potential to include primary or secondary informal caregivers in the nursing home, such as those focused on religious and cultural practices, humour therapy, gender-based groups, animal-assisted therapy or befriending [3, 5, 26,27,28,29]. Conceptually, employing both social isolation and loneliness might have focused the perspective of this review more on the social aspects and less on the personality aspects of these phenomena [13]. Especially the existential dimension of loneliness lies beyond the scope of the interventions included in this review. The concept of involvement limited the search: The interventions we addressed involved primary and secondary informal caregivers in everyday activities and did not try to tackle loneliness and social isolation through occupational activities or therapeutic interventions alleviating maladaptive forms of cognition [26]. This limitation equally holds true for other aspects of primary informal caregiver involvement, such as being informed about care processes or participating in decision-making.

Conclusion

The heterogeneity of definitions and measures of both loneliness and social isolation as well as the lack of sufficient descriptions of intervention mechanisms complicate the evaluation of interventions involving primary or secondary informal caregivers. When addressing the loneliness and/or social isolation in nursing home residents, it is necessary to clarify the dimension of loneliness and social isolation, e.g., the quantity of social interactions, the individual perspective on these encounters and the maintenance and establishment of social relationships. Furthermore, it has to be highlighted in what way the intervention and its components engage with these aspects. The interventions created opportunities for group and dyadic interactions, offered meaningful activities and brought various groups of informal caregivers into the nursing home through introducing technological advances, therapeutic and leisure activities or large-scale managerial changes or care philosophies to the nursing homes. There is especially a lack of evidence on the implementation of large-scale programs or care philosophies focused on the issue of loneliness and social isolation in nursing homes and interventions should increasingly offer multiple ways of participating to cater to person-specific requirements.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Hajek A, Volkmar A, König HH. Prevalence and correlates of loneliness and social isolation in the oldest old: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol; 2023.

Gardiner C, Laud P, Heaton T, Gott M. What is the prevalence of loneliness amongst older people living in residential and nursing care homes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2020;49(5):748–57.

Bethell J, Aelick K, Babineau J, Bretzlaff M, Edwards C, Gibson JL, et al. Social connection in Long-Term Care homes: a scoping review of published research on the Mental Health impacts and potential strategies during COVID-19. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(2):228–. – 37.e25.

Gorenko JA, Moran C, Flynn M, Dobson K, Konnert C. Social isolation and psychological distress among older adults related to COVID-19: a narrative review of remotely-delivered interventions and recommendations. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(1):3–13.

Plattner L, Brandstötter C, Paal P. [Loneliness in nursing homes-experience and measures for amelioration: a literature review] Einsamkeit Im Pflegeheim – Erleben und Maßnahmen Zur Verringerung. Z Gerontol Geriatr; 2021.

Veiga-Seijo R, Miranda-Duro MDC, Veiga-Seijo S. Strategies and actions to enable meaningful family connections in nursing homes during the COVID-19: a scoping review. Clin Gerontologist. 2022;45(1):20–30.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–37.

Lapane KL, Lim E, McPhillips E, Barooah A, Yuan Y, Dube CE. Health effects of loneliness and social isolation in older adults living in congregate long term care settings: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;102:104728.

Boamah SA, Weldrick R, Lee T-SJ, Taylor N. Social isolation among older adults in long-term care: a scoping review. J Aging Health. 2021;0(0):08982643211004174.

Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):129.

ElSadr CB, Noureddine S, Kelley J. Concept analysis of loneliness with implications for nursing diagnosis. Int J Nurs Terminol Classif. 2009;20(1):25–33.

Nicholson NR. Jr. Social isolation in older adults: an evolutionary concept analysis. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65(6):1342–52.

McHugh Power JE, Dolezal L, Kee F, Lawlor BA. Conceptualizing loneliness in health research: philosophical and psychological ways forward. J Theoretical Philosophical Psychol. 2018;38:219–34.

Weiss RS, Loneliness. The experience of emotional and social isolation. Loneliness: The experience of emotional and social isolation: The MIT Press; 1973. p. xxii, 236-xxii.

Mansfield L, Victor C, Meads C, Daykin N, Tomlinson A, Lane J et al. A conceptual review of loneliness in adults: qualitative evidence synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2021; 18(21).

Jansson A, Karisto A, Pitkälä K. Loneliness in assisted living facilities: an exploration of the group process. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(5):354–65.

Ferguson JM. How do the support networks of older people influence their experiences of social isolation in care homes? Soc Incl. 2021;9(4):315–26.

Naik P, Ueland VI. How Elderly residents in nursing homes handle loneliness—from the nurses’ perspective. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:1–6.

Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal Caregiving and its impact on Health: a Reappraisal from Population-Based studies. Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):309–19.

Pereira RF, Myge I, Hunter PV, Kaasalainen S. Volunteers’ experiences building relationships with long-term care residents who have advanced dementia. Dementia. 2022;21(7):2172–90.

Noten S, Stoop A, De Witte J, Landeweer E, Vinckers F, Hovenga N et al. Precious time together was taken away: impact of COVID-19 restrictive measures on social needs and loneliness from the perspective of residents of nursing Homes, Close relatives, and volunteers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(6).

de Sandes-Guimarães LV, Dos Santos PC, Alves C, Cervato CJ, Silva APA, Leão ER. The effect of volunteer-led activities on the quality of life of volunteers, residents, and employees of a long-term care institution: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23(1):151.

Puurveen G, Baumbusch J, Gandhi P. From family involvement to family inclusion in nursing home settings: a critical interpretive synthesis. J Fam Nurs. 2018;24(1):60–85.

Gaugler JE, Mitchell LL. Reimagining Family involvement in residential long-term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(2):235–40.

Akhter-Khan SC, Au R. Why loneliness interventions are unsuccessful: a call for precision health. Adv Geriatric Med Res. 2020;4(3).

O’Rourke HM, Collins L, Sidani S. Interventions to address social connectedness and loneliness for older adults: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):214.

Gardiner C, Geldenhuys G, Gott M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community. 2016;26(2):147–57.

Quan NG, Lohman MC, Resciniti NV, Friedman DB. A systematic review of interventions for loneliness among older adults living in long-term care facilities. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(12):1945–55.

Brimelow RE, Wollin JA. Loneliness in Old Age: interventions to curb loneliness in Long-Term Care facilities. Activities. Adaptation Aging. 2017;41(4):301–15.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synthesis. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

McDermott O, Charlesworth G, Hogervorst E, Stoner C, Moniz-Cook E, Spector A, et al. Psychosocial interventions for people with dementia: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(4):393–403.

Sanford AM, Orrell M, Tolson D, Abbatecola AM, Arai H, Bauer JM, et al. An international definition for nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(3):181–4.

Follmann A, Schollemann F, Arnolds A, Weismann P, Laurentius T, Rossaint R et al. Reducing loneliness in Stationary Geriatric Care with Robots and virtual Encounters-A contribution to the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9).

Moyle W, Jones C, Cooke M, O’Dwyer S, Sung B, Drummond S. Connecting the person with dementia and family: a feasibility study of a telepresence robot. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):7.

Tsai H-H, Tsai YF. Changes in depressive symptoms, social support, and loneliness over 1 year after a minimum 3-month videoconference program for older nursing home residents. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(4):e93.

Tsai H-H, Cheng C-Y, Shieh W-Y, Chang Y-C. Effects of a smartphone-based videoconferencing program for older nursing home residents on depression, loneliness, and quality of life: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Zamir S, Hennessy CH, Taylor AH, Jones RB. Video-calls to reduce loneliness and social isolation within care environments for older people: an implementation study using collaborative action research. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1).

Zamir S, Hennessy C, Taylor A, Jones R. Intergroup ‘skype’ quiz sessions in care homes to reduce loneliness and social isolation in older people. Geriatr (Switzerland). 2020;5(4):1–16.

Zamir S, Hennessy CH, Taylor AH, Jones RB. Feasibility of school students skyping care home residents to reduce loneliness. Computers Hum Behav Rep. 2021;3:100053.

Barbosa Neves B, Franz RL, Munteanu C, Baecker R. Adoption and feasibility of a communication app to enhance social connectedness amongst frail institutionalized oldest old: an embedded case study. Inform Communication Soc. 2017;21(11):1681–99.

Barbosa Neves B, Franz R, Judges R, Beermann C, Baecker R. Can digital technology enhance social connectedness among older adults? A feasibility study. J Appl Gerontol. 2019;38(1):49–72.

Beogo I, Ramdé J, Tchouaket EN, Sia D, Bationo NJC, Collin S et al. Co-development of a web-based hub (esocial-hub) to combat social isolation and loneliness in francophone and anglophone older people in the linguistic minority context (quebec, manitoba, and new brunswick): protocol for a mixed methods interventional study. JMIR Res Prot. 2021;10(9).

Cotten SR, Anderson WA, McCullough BM. Impact of internet use on loneliness and contact with others among older adults: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e39.

Hoang P, Whaley C, Thompson K, Ho V, Rehman U, Boluk K, et al. Evaluation of an intergenerational and Technological intervention for loneliness: protocol for a feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2021;10(2):e23767.

van Dyck LI, Wilkins KM, Ouellet J, Ouellet GM, Conroy ML. Combating heightened social isolation of nursing Home elders: the Telephone Outreach in the COVID-19 outbreak program. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2020;28(9):989–92.

Chu CH, Biss RK, Cooper L, Linh Quan AM, Matulis H. Exergaming platform for older adults residing in long-term care homes: user-centered design, development, and usability study. JMIR Serious Games. 2021;9(1).

McAllister M, Dayton J, Oprescu F, Katsikitis M, Jones CM. Memory keeper: a prototype digital application to improve engagement with people with dementia in long-term care (innovative practice). Dement (14713012). 2020;19(4):1287–98.

Peng F. Wearable memory for healthy aging: share life narratives and make your memory visible. Axon. 2018;8(2):87–94.

Prophater LE, Fazio S, Nguyen LT, Hueluer G, Peterson LJ, Sherwin K, et al. Alzheimer’s Association Project VITAL: a Florida Statewide Initiative using technology to Impact Social isolation and well-being. Front Public Health. 2021;9:720180.

Cheetu S, Medeiros M, Winemaker L, Li M, Bartel L, Foster B et al. Understanding the effects of Music Care on the lived experience of isolation and loneliness in long-term care: a qualitative study. Healthc (Switzerland). 2022;10(3).

Evans SC, Bray J, Garabedian C. Supporting creative ageing through the arts: the impacts and implementation of a creative arts programme for older people. Work Older People. 2022;26(1):22–30.

Foster B, Pearson S, Berends A, Mackinnon C. The Expanding Scope, Inclusivity, and integration of music in Healthcare: recent developments, Research Illustration, and future direction. Healthc (Basel). 2021;9(1).

Ngamaba KH, Heap C. Benefits of running a multicultural singing project among older adults in a naturalistic residential environment: Case studies of Four Residential Care homes in England. J Gerontol Nurs. 2022;48(9):52–3.

O’Rourke HM, Hopper T, Bartel L, Archibald M, Hoben M, Swindle J et al. Music connects us: development of a music-based Group Activity intervention to engage people living with dementia and address loneliness. Healthc (Basel). 2021;9(5).

Horan K, Perkinson MA. Reflections on the dynamics of a Student-Organized intergenerational visiting program to promote Social Connectedness. J Intergenerational Relationships. 2019;17(3):396–403.

Jones M, Ismail SU. Bringing children and older people together through food: the promotion of intergenerational relationships across preschool, school and care home settings. Work Older People. 2022;26(2):151–61.

Rosa Hernandez GB, Murray CM, Stanley M. An intergenerational playgroup in an Australian residential aged-care setting: a qualitative case study. Health & Social Care in the Community; 2020.

Theurer KA, Stone RI, Suto MJ, Timonen V, Brown SG, Mortenson WB. ‘It makes life worthwhile!’ Peer mentoring in long-term care-a feasibility study. Aging Ment Health. 2020:1–10.

Theurer KA, Stone RI, Suto MJ, Timonen V, Brown SG, Mortenson WB. The impact of peer mentoring on loneliness, Depression, and Social Engagement in Long-Term Care. J Appl Gerontol. 2021;40(9):1144–52.

Theurer KA, Stone RI, Suto MJ, Timonen V, Brown SG, Mortenson WB. It makes you feel good to help! An exploratory study of the experience of peer mentoring in long-term care. Can J Aging. 2022;41(3):451–9.

Akinbohun P. Loneliness among older adults and proposed strategic program for intervention. 2015.

Brownie S, Horstmanshof L. The management of loneliness in aged care residents: an important therapeutic target for gerontological nursing. Geriatr Nurs. 2011;32(5):318–25.

Brune K. Culture Change in Long Term Care services: Eden-Greenhouse-Aging in the community. Educ Gerontol. 2011;37(6):506–25.

Angelou K, McDonnell C, Low L-F, du Toit SHJ. Promoting meaningful engagement for residents living with dementia through intergenerational programs: a pilot study. Aging & Mental Health; 2022.

Gurung A, Edwards S, Romeo M, Craswell A. A tale of two generations: Case study of intergenerational living in residential aged care. Collegian. 2022.

Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: results from two Population-Based studies. Res Aging. 2004;26(6):655–72.

Neto F. Psychometric analysis of the short-form UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-6) in older adults. Eur J Ageing. 2014;11(4):313–9.

Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472–80.

Gierveld JDJ, Tilburg TV. A 6-Item scale for overall, emotional, and Social Loneliness:confirmatory tests on Survey Data. Res Aging. 2006;28(5):582–98.

Wardian J, Robbins D, Wolfersteig W, Johnson T, Dustman P. Validation of the DSSI-10 to measure Social Support in a General Population. Res Social Work Pract. 2013;23(1):100–6.

Hawthorne G. Measuring social isolation in older adults: development and initial validation of the friendship scale. Soc Indic Res. 2006;77(3):521–48.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Perach R. Interventions for alleviating loneliness among older persons: a critical review. Am J Health Promot. 2015;29(3):e109–25.

Backhaus R, Hoek LJM, de Vries E, van Haastregt JCM, Hamers JPH, Verbeek H. Interventions to foster family inclusion in nursing homes for people with dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):434.

Jansson AH, Karisto A, Pitkälä KH. Listening to the voice of older people: dimensions of loneliness in long-term care facilities. Aging Soc. 2023;43(12):2894–911.

Peplau LA, Perlman D. Perspectives on loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory,research and therapy. New York: Wiley; 1982.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Eisner R. The meanings of loneliness for older persons. Aging Ment Health. 2020;24(4):564–74.

Chesler J. The effects of playing Nintendo Wii on Depression, sense of belonging, Social Support, and Mood among Australian aged care residents: a pilot study. Federation University Australia; 2015.

Freeman S, Banner D, Labron M, Betkus G, Wood T, Branco E, et al. I see beauty, I see art, I see design, I see love. Findings from a resident-driven, co-designed gardening program in a long-term care facility. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(7):288–300.

Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. How do befriending interventions alleviate loneliness and social isolation among older people? A realist evaluation study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0256900.

Gurrutxaga-Lerma O. Interventions to prevent loneliness in older adults living in nursing homes. 2021.

Du Toit SH, Shen X, McGrath M. Meaningful engagement and person-centered residential dementia care: a critical interpretive synthesis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26(5):343–55.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Stiftung Wohlfahrtspflege Nordrhein-Westfalen under Grant SW-620-7083.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dominique Autschbach and Anika Hagedorn participated equally in the literature search, analysed and interpreted the studies and wrote the manuscript, Margareta Halek advised on the search, analysis and interpretation of the studies and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The review is part of a larger project approved by the ethics committee of the German Society of Nursing Science (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Pflegewissenschaft) with the registration number 20–030.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Autschbach, D., Hagedorn, A. & Halek, M. Addressing loneliness and social isolation through the involvement of primary and secondary informal caregivers in nursing homes: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 24, 552 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05156-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-05156-1