Abstract

Background

Gastric intramural hematoma is a rare disease. Here we report a case of spontaneous isolated gastric intramural hematoma combined with spontaneous superior mesenteric artery intermural hematoma.

Case presentation

A 75-years-old man was admitted to our department with complaints of abdominal pain. He underwent a whole abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan in the emergency department, which showed extensive thickening of the gastric wall in the gastric body and sinus region with enlarged surrounding lymph nodes, localized thickening of the intestinal wall in the transverse colon, localized indistinct demarcation between the stomach and transverse colon, and a small amount of fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity. Immediately afterwards, he was admitted to our department, and then we arranged a computed tomography with intravenously administered contrast agent showed a spontaneous isolated gastric intramural hematoma combined with spontaneous superior mesenteric artery intermural hematoma. Therefore, we treated him with anticoagulation and conservative observation. During his stay in the hospital, he was given low-molecular heparin by subcutaneous injection for anticoagulation therapy, and after discharge, he was given oral anticoagulation therapy with rivaroxaban. At the follow-up of more than 4 months, most of the intramural hematoma was absorbed and became significantly smaller, and the intermural hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery was basically absorbed, which also confirmed that the intramural mass was an intramural hematoma.

Conclusion

A gastric intramural hematoma should be considered, when an intra-abdominal mass was found to be attached to the gastric wall. Proper recognition of gastric intramural hematoma can reduce the misdiagnosis rate of confusion with gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric intramural hematoma is a rare disease. The exact incidence of gastric hematomas is unknown. Intramural hematomas of the gastrointestinal tract are well described in the esophagus and duodenum [1]. However, intramural hematomas in the stomach have been rarely reported [2,3,4]. The main causes of intramural hematomas in the stomach include anticoagulant therapy, coagulopathy, trauma, and aneurysm, as well as idiopathic or congenital (endoscopic treatment and surgery). Here we report a case of spontaneous isolated gastric intramural hematoma combined with spontaneous superior mesenteric artery intermural hematoma.

Case presentation

A 75-year-old man was brought to our emergency department complaining of abdominal pain, predominantly in the upper abdomen and around the umbilicus. The pain started at 3 h and got progressively worse. Physical examination revealed with a blood pressure of 116/ 70 mmHg, heart rate of 60 beats/minute, oxygen saturation of 100% (on room air), and respiratory rate of 17/ minute. The signs of abdominal physical examination were negative except epigastric pressure pain. His past medical history included Parkinson's disease (PD), cerebral ischemia. He had no history of pancreatitis, abdominal trauma and other abdominal surgery except hemorrhoid surgery. He was taking aspirin, cytarabine sodium and medroxyprogesterone. His laboratory findings included erythrocytes count of 4.62*1012/L, hemoglobin level of 133 g/L, hematocrit level of 42.1%, prothrombin time of 11.4 s, activated prothrombin time of 22.2 s, fibrinogen level of 2.17 g/L and normal values of platelets and D-dimer, but a bleeding time was not performed. Blood chemistry laboratory tests were within normal limits. He underwent a whole abdominal CT scan (2022–10-27) in the emergency department, which showed extensive thickening of the gastric wall in the gastric body and sinus region with enlarged surrounding lymph nodes, localized thickening of the intestinal wall in the transverse colon, localized indistinct demarcation between the stomach and transverse colon, and a small amount of fluid accumulation in the abdominal cavity. Afterwards, he was admitted to our department with a diagnosis of gastric neoplasm.

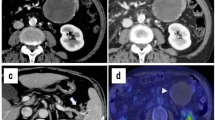

Post-admission physical examination and gastroduodenoscop suggested no significant abnormality. But contrast-enhanced abdominal CT (2022–10-29) suggested hematoma formation on the lateral side of the gastric lesser curvature with perihepatic and abdominopelvic blood/fluid accumulation considered, and multiple peri-gastric lymph nodes enlarged. Interstitial hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery is considered. Computed tomography angiography of the abdominal aorta (2022–10-30) showed a filling defect in the superior mesenteric artery with luminal stenosis, suggesting a possible thrombosis of a vessel coming off the superior mesenteric artery. Concomitantly, hematoma formation on the lateral side of the gastric lesser curvature with perihepatic and abdominopelvic blood/fluid accumulation was considered, and multiple peri-gastric lymph nodes were enlarged. We did not conduct invasive treatment, such as endovascular management or surgery considering that no obvious bleeding site or any mass was found on enhanced abdominal CT and computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the abdominal aorta. Then we took conservative anticoagulation treatment for low-molecular heparin by subcutaneous injection. The patient recovered gradually after conservative anticoagulation treatment without signs of continuous bleeding or increased abdominal pain, and he was discharged after 5 days. Physical examination at the time of discharge suggested blood pressure of 121/63 mmHg, heart rate of 87 beats/minute. His laboratory tests at discharge included erythrocytes count of 3.53*1012/L, hemoglobin level of 104 g/L, hematocrit level of 33.3%. He was given oral anticoagulation therapy with rivaroxaban 20 mg quaque die after discharge.

We performed follow-ups for the patient regularly at the hospital outpatient department. At the follow-up about 1 month after discharge, the patient had no other discomfort such as abdominal pain. The results of the about 1-month follow-up after discharge showed blood pressure of 135/79 mmHg, heart rate of 75 beats/minute. His laboratory tests at discharge included erythrocytes count of 4.71*1012/L, hemoglobin level of 142 g/L, hematocrit level of 42.9%. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT (2022–11-18) suggested the hematoma on the lateral side of the lesser curvature of the stomach is less absorbed than the imaging findings on 2022–10-29, the perihepatic blood/fluid accumulation is less than before, and the pelvic blood/fluid accumulation is essentially similar than before. Intermural hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery with localized entrapment changes. The contrast-enhanced abdominal CT (2023–03-10) of the about 4-month follow-up after discharge showed a small hematoma on the side of the gastric lesser curvature was mostly decreased and the intermural hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery was largely decreased and abdominopelvic blood/fluid accumulation disappeared compared to the imaging findings on 2022–11-18. The timeline from emergency to follow-ups is presented in Fig. 1.

Discussion

Gastric intramural hematoma is rare with only a few cases reported to date [1,2,3,4]. Here we report the first case of which described a spontaneous isolated gastric intramural hematoma combined with spontaneous superior mesenteric artery intermural hematoma. Which is particularly rare.

Within the gastric wall there are a large number of arteries and veins distributed in a network and with a significant number of blood vessels in the submucosal layer [5]. When an artery is injured due to external factors, it can lead to the formation of a hematoma in the submucosal or muscular layer [6]. Spontaneous isolated intramural hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery is characterized by completely thrombosed false lumen which was often considered as a subset of spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery (SIDSMA) and only included few cases in the current literature [7, 8].However, in our case, intramural hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery did not reveal obvious signs of dissection on CTA of the abdominal aorta, but rather suggested the presence of a thrombosis of a vessel coming off the superior mesenteric artery. In our case, this patient had an isolated intramural hematoma of the stomach and an isolated hematoma of the superior mesenteric artery, and there appeared to be no continuity between the two sites.

GIH usually arises secondary to another condition or intervention. The causes of this disease include anticoagulant medication [9], coagulopathy, ulcer disease, aneurysm, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, procedure-related damage, or even in the presence of infection [10,11,12,13,14,15].

Spontaneous isolated intramural hematoma of the SMA is known as a variant form of SIDSMA, and factors likely affecting its nature are complex, including a history of connective tissue disease, fibromuscular dysplasia, atherosclerosis, and elastosis [16, 17]. This patient denied a history of connective tissue disease, lupus erythematosus, giant cell arthritis, mesenteric arthritis, Ehlers-Danlos disease, and it is important to monitor the subsequent literature on this aspect of autoimmune disease. The etiology of the gastric intramural hematoma and SIHSMA in this case is unknown. This patient had a long history of oral aspirin medication, but his coagulation function and platelets were not substantial abnormal, but a bleeding time was not performed. We therefore considered this case to be an idiopathic hematoma. It is important to distinguish it from various submucosal tumors including gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors (GISTs) because of the submucosal tumor-like appearance of the hematoma [18]. In previously published case reports, there have been confusing misclassifications in the diagnosis of intramural hematomas in the stomach.

Symptomatic intramural gastric hematomas are extremely rare, and less than 15 cases underwent surgical treatment [19, 20], and of the cases treated with surgery, only a small percentage of cases had a correct preoperative diagnosis, with a preoperative diagnosis of gastric tumor, a preoperative diagnosis of pancreatic cyst, and a preoperative diagnosis of unknown [20]. In this case, the patient presented with acute abdominal pain and was diagnosed with a gastric tumor in an emergency abdominal (CT) scan, and a revised diagnosis of intramural hematoma was made after performing an enhanced abdominal CT in admission, which was confirmed in the subsequent anticoagulation follow-up treatment. Their treatment recommendations are not standardized due to their rarity [19]. Gastric intramural hematoma is treated in various ways, including surgery and transcatheter arterial embolization, endoscopic and percutaneous drainage, and conservative treatment [20]. In this case the patient successfully recovered with conservative anticoagulation.

Conclusions

Here we reported a case of spontaneous isolated gastric intramural hematoma combined with spontaneous superior mesenteric artery intermural hematoma. A gastric intramural hematoma should be considered, when an intra-abdominal mass was found to be attached to the gastric wall. Proper recognition of gastric intramural hematoma can reduce the misdiagnosis rate of confusion with gastric neoplasm.

Availability of data and materials

All patient data and clinical images adopted are contained in the medical files of Shaoxing People’s Hospital. The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its figures and tables.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- SIDSMA:

-

Spontaneous isolated dissection of the superior mesenteric artery

References

Kones O, Dural AC, Gonenc M, Karabulut M, Akarsu C, Gok I, Bozkurt MA, Ilhan M, Alıs H. Intramural hematomas of the gastrointestinal system: a 5-year single center experience. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85(2):58–62. https://doi.org/10.4174/jkss.2013.85.2.58. Epub 2013 Jul 25. PMID: 23908961; PMCID: PMC3729987.

Imaizumi H, Mitsuhashi T, Hirata M, Aizaki T, Nishimaki H, Soma K, Ohwada T, Saigenji K. A giant intramural gastric hematoma successfully treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Intern Med. 2000;39(3):231–4. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.39.231. PMID: 10772126.

Plojoux O, Hauser H, Wettstein P. Computed tomography of intramural hematoma of the small intestine: a report of 3 cases. Radiology. 1982;144:559–61.

Dhawan V, Mohamed A, Fedorak RN. Gastric intramural hematoma: a case report and literature review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23(1):19–22. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/503129.PMID:19172203;PMCID:PMC2695142.

Eishi H, Yamaguchi K, Hiramatsu Y, Akita K. Intra-mural distribution of the blood vessels in the stomach demonstrated by contrast medium injection: a cadaver study. Surg Radiol Anat. 2021;43(3):389–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-020-02613-5.Epub 2020 Nov 9 PMID: 33164135.

Ng SN, Tan HJ, Keh CH. A belly of blood: A case report describing surgical intervention in a gastric intramural haematoma precipitated by therapeutic endoscopy in an anticoagulated patient. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;26:65–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.06.014.Epub 2016 Jul 18. PMID: 27455112; PMCID: PMC4961227.

Xiaoq Z, Hao M, Lin L, Jiao Y, Zou J, Zhang X, Hong YY. Clinical and CT Angiographic Follow-Up Outcome of Spontaneous Isolated Intramural Hematoma of the Superior Mesenteric Artery. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42(8):1088–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-019-02212-x.Epub 2019 Apr 4 PMID: 30949761.

Yoo J, Lee JB, Park HJ, Lee ES, Park SB, Kim YS, Choi BI. Classification of spontaneous isolated superior mesenteric artery dissection: correlation with multi-detector CT features and clinical presentation. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43(11):3157–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1556-6.PMID: 29550960.

Alabd A, Deitch C. A Rare Case of Gastric Intramural Hematoma in Recurrent Leukemia. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21385. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.21385.PMID:35198296;PMCID:PMC8853736.

Iijima-Dohi N, Shinji A, Shimizu T, Ishikawa SZ, Mukawa K, Nakamura T, Maruyama K, Hoshii Y, Ikeda S. Recurrent gastric hemorrhaging with large submucosal hematomas in a patient with primary AL systemic amyloidosis: endoscopic and histopathological findings. Intern Med. 2004;43(6):468–72. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.43.468.PMID: 15283181.

Sadio A, Peixoto P, Cancela E, Castanheira A, Marques V, Ministro P, Silva A, Caldas A. Intramural hematoma: a rare complication of endoscopic injection therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E141–2. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1214927.Epub 2011 Mar 18. PMID: 21425016.

Sun P, Tan SY, Liao GH. Gastric intramural hematoma accompanied by severe epigastric pain and hematemesis after endoscopic mucosal resection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(47):7127–30. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.7127.PMID:23323020;PMCID:PMC3531706.

Itaba S, Kaku T, Minoda Y, Murao H, Nakamura K. Gastric intramural hematoma caused by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy. Endoscopy. 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E666. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1390867.Epub 2014 Dec 19. PMID: 25526416.

Lee CC, Ravindranathan S, Choksi V, Pudussery Kattalan J, Shankar U, Kaplan S. Intraoperative Gastric Intramural Hematoma: A Rare Complication of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy. Am J Case Rep. 2016;19(17):963–6. https://doi.org/10.12659/ajcr.901248.PMID:27990013;PMCID:PMC5193299.

Lee SJ. A case of gastric intramural hematoma caused by anisakis infection. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2020;2020:9260318. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/9260318.PMID:32685220;PMCID:PMC7336193.

D’Ambrosio N, Friedman B, Siegel D, Katz D, Newatia A, Hines J. Spontaneous isolated dissection of the celiac artery: CT findings in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):W506–11. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.06.0315.PMID: 17515339.

Solis MM, Ranval TJ, McFarland DR, Eidt JF. Surgical treatment of superior mesenteric artery dissecting aneurysm and simultaneous celiac artery compression. Ann Vasc Surg. 1993;7(5):457–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02002130.PMID: 8268091.

Almeida JI, Lima C, Pinto P, Armas I, Santos T, Freitas C. Spontaneous hemoperitoneum as a rare presentation of gastric lesions: Two case reports. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022;91:106769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.106769.Epub 2022 Jan 12. PMID: 35091354; PMCID: PMC8801985.

Spychała A, Nowaczyk P, Budnicka A, Antoniewicz E, Murawa D. Intramural gastric hematoma imitating a gastrointestinal stromal tumor - case report and literature review. Pol Przegl Chir. 2017;89(2):62–5. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0009.9159.PMID: 28537566.

Yoshioka Y, Yoshioka K, Ikeyama S. Large gastric intramural hematoma mimicking a visceral artery aneurysm: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12(1):61. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-018-1595-1.PMID:29510734;PMCID:PMC5840811.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Dr. Hang Yang of the Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University for the English language polishing of this paper.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhenxing Zhang and Guangen Xu developed the protocol. Zhenxing Zhang, Shan Wang and Guolin Zhang analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript text. Zhenxing Zhang, Kelong Tao, Yu Zhang and Danling Guo collected the data. Zhenxing Zhang prepared the Fig. 1. All authors reviewed, read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The patient provided informed consent, which was registered in the medical record. This paper confirms to the principles and requirements of Academic Ethics Committee of Shaoxing Peoples’s Hospital.

Consent for publication

The patient had given written consent for the personal or clinical details along with any identifying images to be published in this study. A copy of this consent to publish is available for review by the editor of the journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Wang, S., Tao, K. et al. Spontaneous isolated gastric intramural hematoma combined with spontaneous superior mesenteric artery intermural hematoma: a rare case. BMC Geriatr 24, 360 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04991-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-024-04991-6