Abstract

Objective

The associations between plasma vitamin B12 level and anemia under different dietary patterns in elderly Chinese people are poorly understood. We aimed to examine the associations between plasma vitamin B12 levels and anemia under different dietary patterns in adults aged 65 years and older in nine longevity areas in China.

Methods

A total of 2405 older adults completed a food frequency questionnaire at the same time as a face-to-face interview. The dietary diversity score (DDS) was assessed based on the food frequency questionnaire, with the low DDS group referring to participants with a DDS score ≤ 4 points. Vitamin B12 levels were divided into two groups of high (>295 pg/mL) and low (≤ 295 pg/mL) with the median used as the cut-off point. Sub-analyses were also performed on older adults divided into tertiles of vitamin B12 levels: low (< 277 pg/mL), medium (277–375 pg/mL) and high (> 375 pg/mL) to study the association of these levels with anemia.

Results

Six hundred ninety-five (28.89%) of these people were diagnosed with anemia and had a mean age of 89.3 years. Higher vitamin B12 levels were associated with a decreased risk of anemia (multi-adjusted OR, 0.59, [95% CI, 0.45 ~ 0.77] P < 0.001) in older adults with a low DDS, whereas no significant association between vitamin B12 levels and anemia was found in older adults with a high DDS in a full-model after adjustment for various confounding factors (multi-adjusted OR, 0.88, [95% CI, 0.65 ~ 1.19], P = 0.41).

Conclusion

The relationship between vitamin B12 levels and the prevalence of anemia was significant only when the level of dietary diversity in the older adults was relatively low. The dietary structure of the population should be taken into consideration in combination in order to effectively improve anemia status by supplementing vitamin B12.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

The relationship between vitamin B12 and the prevalence of anemia was significant only when the dietary structure of the population was relatively simple.

Why does this paper matter?

The dietary structure of the population should be taken into consideration in combination in order to effectively improve anemia status by supplementing vitamin B12 which is more meaningful for public health practice.

Introduction

Anemia is very prevalent in older adults, especially in those older than 85 years [1, 2]. As we know, vitamin B12 plays an important biological role in the hematopoietic process [3,4,5]. Megaloblastic anemia is a type of large cell anemia caused by several reasons including synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid in bone marrow hematopoietic cells or the slow replication rate. However, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency were the most common cause of the disorder. An unhealthy diet, increased consumption of processed food products and digestive system dysfunction were the potential factors of vitamin B12 deficiency among the older adults. The diet of many older adults is always over emphasized because the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension in the aged is relatively high, or because they have a relatively simple dietary structure due to lifestyle and economic reasons, which may in the long term lead to vitamin B12 deficiency and nutritional megaloblastic anemia. Anemia and low plasma vitamin B12 concentrations are very common in older adults who are frequently administered vitamin B12 supplements. But some studies have reported that not all older people with anemia and subnormal vitamin B12 levels benefit from vitamin B12 supplementation alone and it has been suggested that trials are needed to verify whether this patient group should all be treated with hydroxocobalamin [6,7,8,9]. Anemia and vitamin B12 levels in older people are both closely related to dietary habits. According to the dietary guidelines in many countries, such as China, dietary diversity is one of the main characteristics of a healthy diet, with residents guided to implement “dietary diversification” and increase the variety of similar and different kinds of food in their diet. This approach ensures an adequate nutrient intake with dietary diversification improving the quality of the diet and leading to better nutritional and health status [10,11,12]. In practice, Dietary diversity score (DDS) is a good indicator and widely used for studying the relationship between dietary diversity and nutritional balance and health status. The majority of previous studies [6, 13, 14] have focused only on whether the occurrence of anemia is related to vitamin B12 deficiency, but have not paid attention to that if the different dietary patterns have an impact on their relationship. So there was still a controversy on the health benefits of vitamin B12 supplementation or only supplementing vitamin B12 without adjusting the structure of the diet, resulting in a limited improvement in anemia. Our research was conducted to investigate whether there were differences in the correlation between vitamin B12 deficiency and the prevalence of anemia under different dietary diversity levels.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

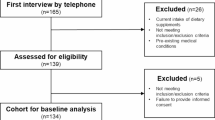

Participants in the study had been enrolled in nine longevity areas from the Healthy Ageing and Biomarkers Cohort Study (HABCS) in China. we conducted a biomarker substudy of the 2017–2018 HABCS in nine longevity regions which covered the central, eastern and southern parts of China in 2017, The details of this survey have been described in a previous report [15]. As shown in Fig. 1, elderly people aged 65 or older who got vitamin B12 tested and had complete anemia related indicators and DDS scoring item were included. Elderly who took multivitamins within 24 hours or took Fe supplements regularly, or diagnosed with digestive system diseases such as gastric ulcer or other serious diseases affecting body function such tumor were excluded from the study. 2405 individuals aged 65 years or over included in the final data analysis. The study was approved by the biomedical ethics committee of National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (IRB:201922). A signed informed consent form was obtained in writing from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

All methods were carried out in accordance to relevant guideline and regulation.

A venous blood (4 mL volume) was collected from each subject. The hemoglobin (Hb) concentration of the subjects was measured by the cyaniding high iron method at a local laboratory. The remainder of the blood samples were sent to the clinical laboratory center of Capital Medical University for testing. The routine hematology tests included hemoglobin, blood cell count and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) that were measured with standard methods by a blood cytoanalyzer. Based on the World Health Organization (WHO) definition and a large study [16], we defined anemia as a Hb level < 130 g/L in men and < 120 g/L in women [17], and moderate/severe anemia as a Hb < 110 g/L in both genders. Morphological classification was performed according to the mean MCV and mean corpuscular hemoglobin contentration(MCHC). The values for the different hematological conditions were: megaloblastic anemia (MCV > 100 FL); normal cell anemia (MCV normal); simple microcytic anemia (MCHC ≥300 g/L and MCV < 80 FL); and hypochromic microcytic anemia (MCHC < 300 g/L and MCV < 80 FL) [18, 19]. As there is no established threshold for defining functional vitamin B12 deficiency [4, 20, 21] in older people, vitamin B12 status was divided into high (>295 pg/mL) and low (≤295 pg/mL) groups. Sub-analyses were also performed on older people with low (< 277 pg/mL), medium (277–375 pg/mL) and high (> 375 pg/mL) vitamin B12 levels to study the relationships between all these levels and anemia.

Determination of vitamin B12 status

Plasma vitamin B12 concentrations were measured using chemiluminescent technology with a reference range of 150-738 pg/mL. Vitamin B12 levels were divided into two groups of high (>295 pg/mL) and low (≤ 295 pg/mL) by median. Sub-analyses were also performed on older adults divided into low (< 277 pg/mL), medium (277-375 pg/mL) and high (> 375 pg/mL) vitamin B12 level by tertiles.

Assessment of DDS

A food frequency questionnaire survey was conducted at the same time as face-to-face interviews with all participants. DDS was evaluated according to a food frequency questionnaire [22, 23] that included nine major categories of food: meat, fish, beans, eggs, fruits, tea, nut, fresh vegetables and agaric. The consumption of these items was recorded as either “regularly or every day nearly”, “not regularly, but at least once/week”, “not every week, but at least once/month”, “not every month, but occasionally”, or “never or rarely”. As oil and cereals are consumed by almost all Chinese people they were not counted in the dietary diversity score [24]. The consumption of any food group as “regularly or every day nearly” or “not regularly, but at least once/week” intake was categorized as one DDS unit, while the other frequency intakes were not classified as a DDS unit. Because a total of nine categories of food were scored, 9 DDS points is the highest, representing the greatest diversity level. We set score ≥ 5 points as high DDS group and score ≤ 4 points as low DDS group. The DDS questionnaire used was developed to evaluate the balance of food intake and diet healthfulness and was composed of many kinds of healthy food items [25]. The scientific validity of the DDS questionnaire has been confirmed in previous studies [10, 24].

Covariates

Some potential confounders were considered by a standardized and structured questionnaire including demographic variables such as residential region, nationality, age, gender, education status, marital status and health behaviors or habits information including current alcohol consumption levels, current smoking habits, self-reported measures of physical activity and physical health. After the face-to-face interview, all the individuals were required to attend a detailed health examinations including measurement of height and weight. All covariate information were defined as follows: demographic information including age (years), gender, residence (urban or rural),education background (illiteracy, primary school, junior middle school and above), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) and current marital status (married or not); lifestyle behavior such as alcohol consumption (current drinker or not), smoking habits (current smoker or not), tea drinking habits (yes or no), exercise regularly (yes or no), use of multivitamin supplements (yes or no), prevalence of one or more of the following diseases including cerebrovascular, heart, digestive, respiratory and kidney disease (yes or no). Comorbidity was defined as the presence of more than one diseases listed above in a person in a defined period. The definition of high blood pressure for the aged was systolic blood pressure(SBP) was≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure(DBP) was≥90 mmHg, or a self-reported diagnosed hypertension by a physician.

Statistical analysis

We compared the continuous and categorical variables between different groups using Student’s T-test or the chi-square test respectively. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for the relationship between vitamin B12 deficiency and anemia, with multiple logistic regression models used to adjust for possible confounders. Variables with a P ≤ 0.05 in the univariate analysis were regarded as likely predictors and mutually adjusted for in the multiple logistic regression models that included age, gender, level of education, nationality, residence, smoking habits, tea drinking habits, physic activity habits and BMI. To study the linear or curvilinear association between vitamin B12 and the odds of suffering from anemia, we performed generalized additive models. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by classifying vitamin B12 levels into three levels and modifying the outcomes of the study population to the diagnosis of severe anemia to evaluate the robustness of the results. All the statistical tests were performed with SAS 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and were two-sided (P < 0.05).

Results

-

(1)

Baseline characteristics of the older adults

The demographic description of the older adults grouped according to the type of anemia are summarized in Table 1. In total, 2405 older people were included in the study, 695 (28.80%) of whom were diagnosed with anemia with a mean age of 89.3 years. The average level of vitamin B12 among the aged with anemia was 308 pg/mL, which was lower than the level of 357 pg/mL in individuals without anemia (Table 1). The prevalence of anemia was 33.86% in older people with lower vitamin B12 levels (vitamin B12 < 295 pg/mL), which was 10% higher than that observed in those with a higher vitamin B12 level (vitamin B12 ≥ 295 pg/mL). However, in the older people with a low vitamin B12 level, the prevalence of anemia changed from 28.90% in the high DDS group to 38.14% in the low DDS group. In older people with a high vitamin B12 level, the prevalence of anemia changed to a lesser degree according to the DDS from 22.53% in the high DDS group to 25.31% in the low DDS group.

-

(2)

The relationship between vitamin B12 status and anemia

Higher vitamin B12 levels can reduce the risk of anemia in the elderly (crude OR, 0.61 [95% CI, 0.51–0.73]; basic adjusted OR, 0.69 [95% CI, 0.57–0.83]; and multi-adjusted analysis that controlled for education level, race, smoking habits, tea drinking habits, and BMI, OR, 0.70[95% CI, 0.57–0.85]), We studied the association between vitamin B12 status and different types of anemia using logistic regression and found that the vitamin B12 status was only significantly associated with the prevalence of megaloblastic anemia and normal cell anemia (Tables 2 and 3).

-

(3)

The relationship between vitamin B12 status and anemia under low DDS

Vitamin B12 status was associated negatively with anemia in older adults with a low DDS (multi-adjusted analysis OR, 0.59 [95% CI, 0.45–0.77]). In contrast, the association between vitamin B12 levels and anemia in older people with a high DDS in the full-model after adjustment for various confounding factors was not statistically significant(multi-adjusted OR, 0.88, [95% CI, 0.65 ~ 1.19],P = 0.41).When we further subdivided the population groups according to the DDS score, the results were still consistent with the above. Subgroup analysis stratified were performed with the basic model, basic-adjusted model, or fully adjusted model. The relationship between vitamin B12 status and the prevalence of anemia including megaloblastic anemia and normal cell anemia was only significant in older people with a low DDS score (P < 0.001 and P < 0.024,respectively), The ORs were 0.49(0.29–0.84),0.71(0.53–0.96)respectively. The statistical results did not change with gender and age group (over 80 years old or under 80 years old) (Tables 2 and 3).

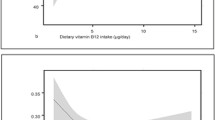

As shown in Fig. 2, we also found a U-shaped association between anemia and vitamin B12 status in the GAMs models and the quadratic models in older adults with a low DDS score, but did not find a similar significant result in older adults with high DDS score. This indicates that older adults may have the lowest risk of overall anemia when their level of vitamin B12 is > 437.94 pg/mL. Among the participants whose vitamin B12 levels were simultaneously below the cut-point (438 pg/mL) and DDS score below 5 points, there was a trend towards a significant decrease in the risk of anemia with increasing levels of vitamin B12. Each 1 pg/mL increase in vitamin B12 level corresponded to a 0.4% lower risk of anemia after adjusting for covariates in the full-model (OR, 0.996 [95%CI, 0.994–0.998]). Compared with participants with lower vitamin B12 levels (≤238 pg/ mL) those with a higher vitamin B12 level (> 238 pg/ mL) had a 36% lower risk of anemia in the full-model (OR, 0.64[95%CI, 0.47–0.86]). However, such a negative or positive association was not observed in participants whose vitamin B12 levels were above 438 pg/ mL or had a DDS score ≥ 5 points, regardless of whether vitamin B12 was considered as either a continuous or categorical variable.

-

(4)

Results of the sensitivity analyses

The results of the sensitivity analyses suggested that our findings were relatively robust and did not show material changes after categorizing the vitamin B12 levels into three levels and modifying the outcome of the study population according to the diagnosis of severe anemia in order to study the relationship between vitamin B12 status and anemia using logistic regression (Table 4).

A significant association between vitamin B12 levels and severe anemia was only observed in older people with a low DDS (OR,0.47(0.27–0.83), P < 0.009.

Discussion

We observed a negative relationship between vitamin B12 status and anemia which only remained significant in older people with a low DDS but not in those with a high DDS. We also found a U-shaped association between anemia and vitamin B12 status in the GAMs models and quadratic models in older people with a low DDS score, but did not find a similar significant result in older people with high DDS score. When the vitamin B12 level was close to 438 pg/mL the risk of anemia was lowest when analyzed by smoothing function fitting.

The negative association between vitamin B12 and anemia was only found among the participants who simultaneously had a vitamin B12 level below the cut-point(438 pg/mL) and a DDS score below 5 points at the same time. We therefore speculate that when the elderly have high levels of vitamin B12 or diversified diets, the risk of anemia don’t always further decrease with an increase of vitamin B12 level. Zhou [26] considered that iron deficiency anemia due to a lack of iron makes vitamin B12 unable to participate in the synthesis of erythrocyte DNA, causing iron deficiency anemia and increasing the serum levels of vitamin B12. This may obscure the real relationship between vitamin B12 levels and anemia especially when the serum vitamin B12 level is high. Because of the nondeterminacy of the dose relationship between vitamin B12 depletion and the onset of various diseases and the various laboratory methods for measuring vitamin B12, functional vitamin B12 deficiency is difficult to define. No universal gold standard was set for diagnosing cobalamin deficiency and the criteria for dividing older people into deficient or sufficient groups remains unclear [7, 27]. However, the following guidelines were used by some clinicians to classify cobalamin levels: < 200 pg/mL, deficiency is present, 200-300 pg/mL, deficiency possible, and > 300 pg/mL, deficiency is unlikely [28]. Our study classified older people into subnormal and normal groups according to the median or percentile of vitamin B12 status. The median value of vitamin B12 used in our study was 295 pg/mL, which is similar to the guidelines mentioned above. In many other recent studies in Western societies the proportion of people with a high vitamin B12 level was greater than that of people with a subnormal vitamin B12 level, with a median level of 392 pg/mL or higher [29,30,31,32]. However, the results of studies in elderly Chinese people showed that the level of vitamin B12 was relatively low and that the levels varied greatly in different studies [33, 34]. A study in people living in Southern China [35] reported that the adjusted mean level of plasma vitamin B12 was 260 pmol/L (352 pg/mL), while the level of people living in Northern China was 189 pmol/L (256 pg/mL), with levels tending to decrease with age. Our study showed that the mean age of older people with a low plasma vitamin B12 level was greater than that of those with a high level, indicating that older people are more likely to have vitamin B12 deficiency.

Serum or plasma vitamin B12 deficiencies are listed as established causes of anemia [36, 37], with many previous studies having investigated the relationship between vitamin B12 status and anemia. Most of these researches have focused on the negative association between vitamin B12 status and higher risk of macrocytic anemia, with only a few studies exploring the relationship between vitamin B12 status and different types of anemia. In addition, few studies have studied whether the lower vitamin B12 levels can increase the risk of different types of anemia by including dietary structure in the analyses.

The progress of DNA synthesis, erythropoiesis, and cell division, vitamin B12 is an important essential micronutrient. Therefore, DNA replication, cell division and S-phase progression in erythroblasts can be influenced by vitamin B12 deficiency [38]. Patients with very low levels of vitamin B12 may suffer from macrocytosis and anemia because of overproduction of protein in erythroblasts [39]. Vitamin B12 cannot be synthesized in the body and is completely dependent on dietary sources, especially all kinds of meat [40]. A systematic review of 25 studies on vitamin B12 deficiency and anemia in the aged showed inconsistent results [7]. There were three possible explanations why we observed a negative relationship between vitamin B12 status and anemia which was only remained significant in older people with a low DDS not in that with a high DDS. First, an inadequate dietary intake of foods rich in vitamin B12, such as animal products and food-cobalamin malabsorption (FCM) were the main causes of vitamin B12 deficiency [34]. Some studies have reported that malabsorption primarily affects people aged 60 years and older. About 40% of patients with an unexplained low serum vitamin B12 level may have FCM [41]. Although the causes for FCM are unclear, FCM explains why vitamin B12 depletion occurs along with aging and was the most common cause of vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly population. The most probable factors that contribute to malabsorption of vitamin B12 in older people include intestinal microbial proliferation, chronic alcoholism, gastric reconstruction, pancreatic enzyme deficiency, sjogren syndrome and long-term ingestion of drugs such as antacids, biguanides, H2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors [42, 43]. If the older people had a balanced diet, but the vitamin B12 status remained low, it suggests that they may not only have vitamin B12 deficiency, but often accompanied by intestinal absorption and intestinal immunity problems. Then, malabsorption could lead to other anemia related deficiencies caused by Fe or folic acid, which are also important causes of nutritional anemia [44, 45]. This may disturb the relationship between vitamin B12 level and anemia. We know that because iron deficiency causes microcytosis and vitamin B12 deficiency causes macrocytosis, if patients suffer from concomitant deficiencies in iron and vitamin B12 at the same time, they may present with anemia with normal-sized RBCs (normocytic anemia) instead [46, 47]. The second explanation is that anemia due to nutritional deficiency is an acquired problem because of the insufficient quantity of bioavailable essential hematopoietic nutrients such as Fe, vitamin B12 and folic for red blood cell and hemoglobin synthesis. The older people with a high DDS had a balanced dietary intakes of various nutrients, which may promote their absorption to a certain extent.

Because the synthesis of red blood cells also involves the effective utilization of various nutrients, even if the level of vitamin B12 status is relatively low, a balanced diet may improve the bioavailability of vitamin B12 level in the process of erythropoiesis, so as to reduce the actual risk of anemia and modify the relationship between vitamin B12 level and anemia [48]. The third explanation is that in addition to the insufficient intake of vitamin B12, the older adults with a low DDS score also have insufficient intake of other anemia related nutrients. For example, vegetarians may have insufficient Fe intake, which further increases the possibility of anemia [49]. The dietary variety and the absorption capacity of various nutrients always declines with advancing age [50]. Dietary nutritional habits, vitamin B12, and serum iron deficiency therefore influence each other and in combination also affect the type of anemia that may develop. Low vitamin B12 and symptoms due to vitamin B12 deficiency especially neurological which can be irrevesible are usually corrected with supplements [51]. However, the effect of this supplementation on haematological parameters in community-dwelling older people with low vitamin B12 is not consistent [9], not all vitamin B12 administration can effectively improve the haemoglobin concentrations and MCV among older people [8, 9, 52]. Some other causes such as chronic inflammation, other hematological diseases, polypharmacy may play a role in the development of vitamin B12 deficiency and anaemia [53]. Sometimes multiple co-existing deficiencies of other nutrients such as Fe and folic acid may interfere with the clinical symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency. Currently, there is no an independent gold standard for unequivocal characterization of vitamin B12 deficiency nor an agreement on how to treat (in relation to cobalamin preparation, dosage, formulation, intensity and duration of treatment), or on how and when to monitor the effects of vitamin B12 supplementation [43, 54]. Therefore, we should not only directly and blindly supplement vitamin B12 to improve the anemia symptoms of vitamin B12 deficient among older people. Both the causes of vitamin B12 deficiency and the dietary structure of the population need to be taken into consideration to decide whether to supplement vitamin B12 alone or associated with nutritional intervention for FCM prevention and treatment is needed.

Strengths

To date, most previous studies on whether the anemia was associated with vitamin B12 deficiency were carried out in Western populations whose dietary habits are very different from those in China. The vitamin B12 level and prevalence of anemia in the elderly Chinese population are also different from that of other countries. It is therefore very important to carry out further analyses on the dietary habits of older people in China. The large number of people selected for our study lived in nine provinces in Northern and Southern China and were representative of the population in these areas. By combining dietary diversity with the relationship between vitamin B12 levels and different types of anemia in our analyses and a negative association between vitamin B12 and anemia was only found among the participants whose vitamin B12 levels were below the cut-point(438 pg/ mL) and DDS score were below 5 points at the same time, we consider that the results may be more meaningful for public health practice.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, it’s a cross-sectional design .Furthermore, the fact that classification of the dietary score can be further refined. Thirdly, our evaluation of the vitamin B12 levels was based only on plasma vitamin B12 concentration. Concomitant deficiencies in cobalamin and folate are often found although we did not measure vitamin B12 metabolites and other anemia-related dietary nutrients including folic acid and serum iron which are closely related to dietary nutrition and anemia.

Conclusions

We found that the relationship between vitamin B12 and the prevalence of anemia, mainly macrocytic anemia and normal cell anemia was only statistically significant when the dietary structure of the elderly population was relatively simple. In addition, a negative association between vitamin B12 and anemia was only observed among the participants who simultaneously had a vitamin B12 level below the cut-point and a DDS score below 5 points. In contrast, if the level of dietary diversity in the elderly was relatively high. The dietary structure of the population, the vitamin B12 levels and the type of anemia should therefore be taken into consideration together in order to improve anemia status by supplementing vitamin B12. We encourage further study on these relationships and hope our findings will both inform continuing debate on vitamin B12 and anemia under different dietary diversity levels and influence efforts to treat anemia in older people from a perspective of low vitamin B12 status under different dietary diversity levels.

Availability of data and materials

This study was based on the datasets from the Healthy Ageing and Biomarkers Cohort Study(HABCS). The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due the data shared by multiple researchers but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Beghé C, Wilson A, Ershler WB. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in geriatrics: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(Suppl 7A):3s–10s.

Guralnik JM, Eisenstaedt RS, Ferrucci L, Klein HG, Woodman RC. Prevalence of anemia in persons 65 years and older in the United States: evidence for a high rate of unexplained anemia. Blood. 2004;104(8):2263–8.

Andrès E, Noureddine HL, Noel E, Kaltenbach G, Abdelgheni MB, Perrin AE, et al. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patients. CMAJ. 2004;171(3):251–9.

Wolters M, Ströhle A, Hahn A. Cobalamin: a critical vitamin in the elderly. Prev Med. 2004;39(6):1256–66.

Longo D, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. Harrison's principles of internal medicine, vol. 204. 18th ed. Practitioner; 2011. p. 831–7.

Elzen WD, Westendorp R, Frölich M, Ruijter WD, Assendelft J, Gussekloo J. Vitamin B12 and folate and the risk of Anemia in old age: the Leiden 85-plus study. JAMA Intern Med. 2008;168(20):2238–44.

Elzen WD, Weele GMVD, Gussekloo J, Westendorp RG, Assendelft WJJ. Subnormal vitamin B12 concentrations and anaemia in older people: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2010;10(1):42.

Hvas AM, Ellegaard J, Nexø E. Vitamin B12 treatment normalizes metabolic markers but has limited clinical effect: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Chem. 2001;47(8):1396–404.

Antonia FS, Jacobijn G, Bermingham LW, Allen E, Dangour AD, Eussen SJPM, et al. The effect of vitamin B12 and folic acid supplementation on routine haematological parameters in older people: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(6):785–95.

Lv YB, Kraus VB, Gao X, Yin ZX, Shi XM. Higher dietary diversity scores and protein-rich food consumption were associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality in the oldest old. Clin Nutr. 2019;39(7):2246–54.

Hamedi-Shahraki S, Norouzadeh M, Amirkhizi F. Decreased dietary diversity is a predictor of metabolic syndrome among adults a cross-sectional study in Iran. Top Clin Nutr. 2021;36(4):272–83.

Kennedy G, Ballard T, Dop MC. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Rome, Italy: FAO of the UN; 2013.

Lippi G, Montagnana M, Targher G, Guidi GC. Vitamin B12, folate, and anemia in old age. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):716.

Chui CH, Lau FY, Wong R, Soo OY, Cheng G. Vitamin B12 deficiency - need for a new guideline. Nutrition. 2001;17(11–12):917–20.

Lv Y, Mao C, Yin ZX, Li F, Shi XM. Healthy ageing and biomarkers cohort study (HABCS): a cohort profile. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e026513.

Culleton BF, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn BR. Impact of anemia on hospitalization and mortality in older adults. Blood. 2006;107(10):3841–6.

World Health Organization. Nutritional anaemias: Report of a WHO scientific group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1968. Technical report series No. 405.

Izaks GJ, Westendorp RG, Knook DL. The definition of Anemia in older persons. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1714–7.

Tyler RD, Cowell RL. Classification and diagnosis of anaemia. Comp Haematol Int. 1996;6(1):1–16.

Elzen WPJD, Gussekloo J. Anemia in older persons. Neth J Med. 2011;69(6):260–7.

Mézière A, Audureau E, Vairelles S, et al. B12 deficiency increases with age in hospitalized patients: a study on 14,904 samples. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(12):1576–85.

Qiu L, Sautter J, Gu D. Associations between frequency of tea consumption and health and mortality: evidence from old Chinese. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(9):1686–97.

Lee YH, Chang YC, Lee YT, Shelley MC, Liu CT. Dietary patterns with fresh fruits and vegetables consumption and quality of sleep among older adults in mainland China. Sleep Biol Rhythm. 2018;16(3):293–305.

Yin Z, Fei Z, Qiu C, et al. Dietary diversity and cognitive function among elderly people: a population-based study. J Nutr Health Ageing. 2017;21(1):1089–94.

Krebs-Smith SM, Pannucci TE, Subar AF, et al. Update of the healthy eating index: HEI-2015. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(9):1591–602.

Zhou M. Observation of serum vitamin B12 in some hematological diseases. Med Inform. 2011;24(10):6420–1.

Savage DG, Lindenbaum J, Stabler SP, Allen RH. Sensitivity of serum methylmalonic acid and total homocysteine determinations for diagnosing cobalamin and folate deficiencies. Am J Med. 1994;96(3):239–46.

Orton CC. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in the older adult. J Nurse Pract. 2012;8(7):547–53.

Abrahamsen JF, Bjørke-Monsen AL, Ranhoff AH, et al. No association between subnormal serum vitamin B12 and anemia in older nursing home patients. Eu Geriatr Med. 2019;11(5):247–54.

Zulfiqar AA, Sebaux A, Dramé MD, Pennaforte JL, Novella JL, Andrès E. Hypervitaminemia B12 in elderly patients: frequency and nature of the associated or linked conditions. Preliminary results of a study in 190 patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(10):e63–4.

Arendt JFB, Nexø E. Unexpected high plasma cobalamin/proposal for a diagnostic strategy. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51(3):489–96.

Brah S, Chiche L, Mancini J, Meunier B, Arlet JB. Characteristics of patients admitted to internal medicine departments with high serum cobalamin levels: results from a prospective cohort study. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(5):e57–8.

Wang Y, Zheng Y, Fang Y, Zhang W. Status of vitamin B12 deficiency in the elderly Chinese community people. Health. 2015;7(12):1703–9.

Wang YH, Yan F, Zhang WB, et al. An investigation of vitamin B12 deficiency in elderly inpatients in neurology department. Neurosci Bull. 2009;25(4):209–15.

Brouwer I, Verhoef P. Folic acid fortification: is masking of vitamin B-12 deficiency what we should really worry about? Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(4):897–8.

Bach V, Schruckmayer G, Sam I, Kemmler G, Stauder R. Prevalence and possible causes of anemia in the elderly: a cross-sectional analysis of a large European university hospital cohort. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:1187–96.

Goodnough LT, Schrier SL. Evaluation and management of anemia in the elderly. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(1):88–96.

Irizarry MC, Gurol ME, Raju S, et al. Association of homocysteine with plasma amyloid β protein in aging and neurodegenerative disease. Neurol. 2005;65(9):1402–8.

Hung CJ, Huang PC, Lu SC, et al. Plasma homocysteine levels in Taiwanese vegetarians are higher than those of omnivores. Nutr J. 2002;132(5):152–8.

Robert C, Grimley EJ, Schneede J, et al. Vitamin B12 and folate deficiency in later life. Age Ageing. 2004;33(1):34–41.

Carmel R, Aurangzeb I, Qian D. Associations of food-cobalamin malabsorption with ethnic origin, age, helicobacter pylori infection, and serum markers of gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(1):63–70.

Zik C. Late life vitamin B12 deficiency. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35(3):319–25.

Cuskelly GJ, Mooney KM, Young IS. Symposium on micronutrients through the life cycle folate and vitamin b12 : friendly or enemy nutrients for the elderly. P Nutr Soc. 2007;64:548–58.

Senewiratne B, Hettiarachchi J, Senewiratne K. Vitamin B12 absorption in megaloblastic anaemia. Br J Nutr. 1974;32(3):491–501.

Obeagu EI. A review on nutritional Anaemia. IJAMR. 2018;5(4):11–5.

Kwok TCY, Cheng G, Woo J, Lai WK, Pang CP. Independent effect of vitamin B12 deficiency on hematological status in older Chinese vegetarian women. Am J Hematol. 2010;70(3):186–90.

Chang JYF, Wang YP, Wu YC, Cheng SJ, Chen HM, Sun A. Blood profile of oral mucosal disease patients with both vitamin B12 and iron deficiencies. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114(6):532–8.

Eaton SB, Konner M. Paleolithic nutrition.A consideration of its nature and current implications. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(5):283–9.

Silva ND, Davis B. Iron, B12 and folate. Med. 2013;41:204–7.

Huang YC, Wahlqvist ML, Lee MS. Appetite predicts mortality in free-living older adults in association with dietary diversity A NAHSIT cohort study. Appetite. 2014;83(1):89–96.

Andrès E, Zulfiqar AA, Vogel T. State of the art review: oral and nasal vitamin B12 therapy in the elderly.QJM. Int J Med. 2020;1:5–15.

Hughes D, Elwood P, Shinton NK, Wrighton RJ. Clinical trial of the effect of vitamin B12 in elderly subjects with low serum B12 levels. Br Med J. 1970;1(5707):458–60.

Nemeth E, Ganz T. Anemia of inflammation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:671–81.

Schneede J. Prerequisites for establishing general recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency and cost-utility evaluation of these guidelines. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2003;63(5):369–75.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The HABCS in 2017 was supported by National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (G030702). The National Natural Sciences Foundation of China had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LL organized and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. YL helped supervise the field activities. LL and YL contributed to the conception and design for the study, wrote the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. JHZ, FZ, FL and YCL collected the data. YL, YLQ and CC contributed to data cleaning. YCL, JYC, SJ, YWL and HG conducted HABCS and directed its implementation, including quality assurance and control, dataset management and analytic strategy. XMS and YL revised the manuscript critically for important content. All authors read and approved the final version to be published, and agreed both to be personally accountable for the their own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work. XMS and YL are the guarantor of this work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the biomedical ethics committee of National Institute of Environmental Health, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (IRB:201922). A signed informed consent form was obtained in writing from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Zhou, J., Chen, C. et al. Vitamin B12 is associated negatively with anemia in older Chinese adults with a low dietary diversity level: evidence from the Healthy Ageing and Biomarkers Cohort Study (HABCS). BMC Geriatr 24, 18 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04586-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04586-7