Abstract

Background

Pain is often neglected in disabled older population, especially in Taiwan where the population of institutional residents is rapidly growing. Our study aimed to investigate pain prevalence and associated factors among institutional residents to improve pain assessment and management.

Methods

This nationwide study recruited 5,746 institutional residents in Taiwan between July 2019 and February 2020. Patient self-report was considered the most valid and reliable indicator of pain. A 5-point verbal rating scale was used to measure pain intensity, with a score ranging from 2 to 5 indicating the presence of pain. Associated factors with pain, including comorbidities, functional dependence, and quality of life, were also assessed.

Results

The mean age of the residents was 77.1 ± 13.4 years, with 63.1% of them aged over 75 years. Overall, 40.3% of the residents reported pain, of whom 51.2% had moderate to severe pain. Pain was more common in residents with comorbidities and significantly impacted emotions and behavior problems, and the mean EQ5D score, which is a measure of health-related quality of life (p < .001). Interestingly, pain was only related to instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and not activities of daily living (ADL). On the other hand, dementia was significantly negatively associated with pain (p < .001), with an estimated odds of 0.63 times (95% CI: 0.53–0.75) for the presence of pain when compared to residents who did not have dementia.

Conclusions

Unmanaged pain is common among institutional residents and is associated with comorbidities, IADL, emotional/behavioral problems, and health-related quality of life. Older residents may have lower odds of reporting pain due to difficulty communicating their pain, even through the use of a simple 5-point verbal rating scale. Therefore, more attention and effort should be directed towards improving pain evaluation in this vulnerable population .

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pain is a subjective experience that involves an unpleasant sensory and emotional response, usually associated with actual or potential tissue damage [1]. As people age, they are more likely to develop various comorbidities, and increase the risk of experiencing pain compared to individuals belonging to other age groups [2]. As the global population ages, there is a high prevalence of pain in the elderly, as reported in previous studies [3,4,5]. Unfortunately, pain in geriatric individuals is often neglected, particularly in those with functional declines and dementia. We know that people with persistent pain may worsen comorbidities and eventually lead to neurophysiological disorders, such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders.

In recent years, there has been an increasing number of adults over 65 years living in institutions [6]. The National Study of Long-Term Cares Providers (2013–2014) indicated that approximately 1.4 million people in the United States live in nursing homes [7]. In addition, as of 2018, Taiwan has become an aging society, with over 3.3 million adults over 65 years of age, which is more than 14% of the population [8]. There is a rapidly growing need for care in the aging population, with at least over 250,000 people receiving long-term care services in 2019. Identifying painful conditions in frail institutional residents and conducting comprehensive assessments of potential factors associated with pain, including limited functional abilities that may occur during aging, are crucial to target specific domains.

Previous research has revealed that estimated pain experiences in older adults within institutions ranged from 45 to 80% [9]. Institutional residents, who frequently have multiple comorbidities, are particularly prone to daily pain [10], and more than 20% of these residents receive inadequate or no analgesic treatment [6, 11]. In addition to aging, chronic illnesses are associated with a greater incidence of pain. A review study reported that patients with neuropathological disorders have a high prevalence of pain [12]. Some patients with stroke also showed increased neuronal hyperexcitability and complaints of post-stroke pain [13].

Hoffmann et al.found more than 50% of the 4,584 nursing home residents in Germany had dementia based on the health insurance claims data [14]. Similarly, a recently published nationwide survey in Taiwan showed that the institutional prevalence of dementia was 87.1%, including very mild dementia [15]. An increased in documented dementia cases has been reported especially in institutions in Taiwan [16] and the estimated global prevalence was forecasted to triple by 2050 [17]. The future outcome of demented patients in Asia has been reported to be highly associated with cerebrovascular diseases [18], which can further deteriorate cognition [19]. Accurate evaluating pain in older residents is challenging, as they often have varying degrees of impaired cognitive and communication functions [20, 21].

Additionally, pain in institutional residents may be associated with a decline in their daily function and subsequent disability. Chronic pain has been shown to reduce activities of daily living (ADL) and physical activity in community-dwelling older people [22]. A nationwide cross-sectional study conducted in Spain reported that more than 50% of adults with chronic pain experience some limitations in ADL [23]. A population-based survey indicated that higher age and pain intensity significantly affected ADL [24].

Pain is a significant problem among institutional residents globally, and more research is needed to improve their care, particularly in countries like Taiwan where the population of older adults is rapidly growing. Therefore, our study aims to investigate the prevalence of pain and its associated factors among institutional older adults in Taiwan, with a larger sample size, providing further insights into the relationship between pain and comorbidities, cognition, daily functional dependence, and quality of life. This research is essential to improve care for disabled older adults in Taiwan and other countries facing a similar demographic shift.

Methods

This cross-sectional study utilized data from the Taiwan National Health Research Institutes and was conducted between July 2019 and February 2020. The study population included 5,746 institutional residents from 22 counties and cities in Taiwan. A total of 299 long-term care institutions were recorded, including 164 welfare institutions for elderly people, 125 general nursing homes, and 10 veteran homes. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Research Ethics Committee of National Health Research Institutes (EC1080502), and written informed consent was obtained from the residents before their participation. If self-determination was not possible, proxy consent was requested from their families. All methods were conducted according to the Helsinki guidelines and regulations. The response rate was 87.7%, and socio-demographic parameters, pain experiences, current comorbidities (within 6 months), emotional status, and physical functional disabilities were obtained from residents through questionnaires (self- or other-report). In addition, all interviewers or specialists who participated in the study underwent a training course to reduce inter-interviewers’ bias in the cognitive dysfunction and dementia assessment.

The primary outcome of this study was pain score, which was measured by assessing the intensity of pain using a verbal rating scale. The scale consisted of five-points of assessment that corresponded to the following level of pain: 1 (no pain), 2 (slight pain), 3 (moderate pain), 4 (severe pain), and 5 (unbearable pain). This 5-point rating scale is a reliable and valid tool for assessing pain in older adults, both with and without cognitive impairment [25,26,27,28,29]. Pain scores that ranged from 2 to 5 indicated the presence of pain, while scores of 0 to 1 indicated the absence of pain [30]. The study also collected socio-demographic variables, including age (≤ 65, 66–75, > 75 years), sex, and educational level (illiteracy, ≤ 6 years, and > 6 years).

We conducted further analyses to examine the presence of cognitive dysfunction and the prevalence of diagnosed dementia among institutional residents. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was commonly used as a brief screening tool for cognitive disorders [31], with lower scores indicating more severe cognitive problems. However, the optimal cutoff values for the MMSE are inconclusive. We used the MMSE questionnaire in the Taiwan/Mandarin version published by Psychological Assessment Resources and compared different cutoff points with the existence of pain. First, we defined a cutoff-score of 27 (26 or below) for the MMSE as indicative of cognitive impairment in highly educated individuals based on previous research [32]. Participants who scored below 27 were further categorized into three levels: mild (20 to 26 points), moderate (10 to 19 points), and severe (0 to 9 points). Second, as individuals with lower levels of formal education may have reduced cognitive performance on the MMSE [33,34,35], the MMSE cut-off values were adjusted to minimize the effects of educational level. For literate participants, a score below 25 on the MMSE indicated cognitive impairment, while for illiterate participants, the. threshold was set at a score below 14. Additionally, institutional residents who had a diagnosed dementia certificate from a hospital or by a neurologist were surveyed. The severity of dementia was also investigated using the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR 0 to 3 scores), which is a reliable tool for evaluating cognitive performance across six domains [36]. To classify the severity of dementia, five levels of dementia were defined as follows: 0 (normal), 0.5 (very mild dementia), 1 (mild dementia), 2 (moderate dementia), and 3 (severe dementia).

A painful condition often impairs the moods, functional dependence, and health-related quality of life of individuals. The presence of pain was investigated in relation to several factors including activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), emotional or behavioral problems, and the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire as measured by the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire. ADL was scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning in basic self-care tasks [37]. IADL was scored from 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating independence in performing instrumental activities of daily life [38]. The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire consists of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression [39]. A higher score indicates better quality of life, with scores ranging between -1.0259 (the worst health status) and 1 (full health) [40]. The covariates of chronic illness in the residents were also examined.

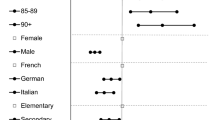

Institutional residents in the study were divided into two groups based on their experience of pain, and various covariates, such as demographics, comorbidities, cognitive functions, and quality of life (as listed in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4), were compared between the two groups. Continuous data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and analyzed using Student’s t-test, while categorical data were expressed as number (%) and analyzed using the chi-square test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A total of 30 comparisons were made in this study, and to account for multiple testing, the significance level was adjusted to 0.0017 (0.05/30) using the Bonferroni correction. Therefore, a p-value less than 0.0017 was considered statistically significant. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, sex, and educational level.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographics and baseline MMSE scores of the study population, along with a comparison of those who had pain and those who did not. The sample included 5,746 institutional residents with a mean age of 77.1 ± 13.4 years, of whom18.4% were aged ≤ 65 years, 18.5%. were aged 66–75 years, and 63.1% were aged > 75 years. Of the residents, 49.2% (n = 2,829) were men, 81.6% (n = 4,689) were aged > 65 years, and 26.8% (n = 1,496) had completed at least junior high school education. The mean MMSE score was 17.0 ± 6.66. Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, educational level, and mean MMSE score, showed no association with the presence of pain. Furthermore, up to 40.3% (n = 2,318) of the institutional residents reported different levels of pain, with 1,131 residents reporting slight pain, 553 (9.6%) reporting moderate pain, 282 (4.9%) reporting severe pain, and 352 (6.1%) reporting unbearable pain (data not shown). These findings suggest that undertreated pain is not uncommon among institutional residents.

Table 2 shows the current comorbidities in institutional residents and their association with pain. Nearly all residents (97.8%) had comorbidities. Among the most common comorbidities were hypertension (59.3%), stroke (31.4%), diabetes mellitus (30.2%), and dementia (22.6%). The residents with comorbidities were significantly more likely to experience pain, with an odds ratio of 2.24 (95% CI: 1.46–3.43) after adjusting for potential confounders (age, sex, and educational level). We further analyzed the association between pain and specific comorbidities and found that bone disorders (arthritis, bone fracture, osteoporosis) (OR: 1.53, p < 0.0001), urogenital disorders (OR: 1.31, p < 0.0009), and spinal cord injury (OR: 2.71, p < 0.0001) were significantly associated with pain in institutional residents after adjusting for potential confounders.

Table 3 presents the relationship between self-report pain, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia among institutional residents. There was no significant association between pain and cognitive dysfunction, defined as MMSE ≤ 26 (p = 0.89 and OR: 0.98, 95% of CI: 0.72–1.33). After adjusting for educational level (literacy or illiteracy), cognitive impairment defined as MMSE < 25 for literacy and MMSE < 14 for illiteracy was not associated with pain. However, our study found a high prevalence of dementia in older institutional residents, and a significant negatively association was observed between dementia and pain (p < 0.001 and OR: 0.63, 95% CI: 0.53–0.75) compared to residents without dementia. The distribution of dementia was determined using four criteria: 1. confirmation from hospital, 2. CDR ≥ 0.5 and MMSE < cutoff point (MMSE < 25 for literacy and MMSE < 14), 3. CDR ≥ 1 but MMSE ≥ cutoff point, 4. CDR ≥ 1. Institutional residents with a hospital certificate of dementia diagnosis and those with CDR scores of 1 or above were less likely to report pain, with a p-value less than 0.001, indicating a statistically significant difference. Additionally, a post-hoc analysis of the data based on CDR scores was also conducted, and the results showed no significant difference in the likelihood of reporting pain across different CDR scores.

Table 4 presents the association of pain with functional dependence, emotional/behavioral problems, and quality of life among institutional residents. The majority of residents who reported pain had severe or total dependence in ADL and IADL. However, the mean ADL score and the severity of ADL were not statistically significant in relation to self-reported pain. In contrast, residents who reported pain had higher mean IADL scores than residents who did not report pain (p < 0.001), and the moderate dependent group had an estimated 2.08 times the odds of experiencing pain when compared to residents who had no dependence in IADL. These findings suggest that residents with higher IADL scores reported more pain experience. Additionally, we found a strong association between pain and emotional/behavioral problems (p = 0.0002 and OR: 1.23, 95% of CI: 1.10–1.38), and pain had a significantly negative effect on quality of life, using the ED5Q assessment tool (p < 0.001).

Discussion

This study is the first large-scale and nationwide study in Taiwan, to our knowledge, that aim to examine pain prevalence and its effects on institutional older residents. The study enrolled 5,746 residents from various institutions in Taiwan, with over 60% aged over 75 years. The results showed that pain is prevalent among institutional residents, with 40.3% experienced pain, and more than half of them (51.2%) having moderate or more pain. These finding suggest that undermanaged pain is a common problem among institutional residents, which is consistent with the prevalence of pain reported in nursing home in other countries such as the US, Canada and Sweden (ranging from 40 to 80%) [41]. The study also found that pain was commonly associated with comorbidities such as bone disorders, urogenital disorders, and spinal cord injury. However, different degrees of dementia were negatively associated with pain. The study also found that the IADL level, but not ADL, was significantly associated with pain. Pain was found to significantly increase mood- and behavior-related problems, and have a significant negative impact on quality of life.

Atee et al [42] conducted a retrospective cross-sectional analysis and found a high prevalence of pain (54.6%-78.6%) among individuals with dementia. Similarly, a review study reported that approximately 60% to 80% of nursing home resident with dementia experienced pain [43]. In the present study, which included over 80% of residents with varying stages of dementia, those with a hospital diagnosis certificate of dementia and those with CDR scores of 1 or above were significantly less like to report pain using a 5-point verbal rating scale. This may be due to reduced communication abilities in these populations, even with a simple numeric scale. A systematic review study proposed that self-report by the patients is a standard tool for pain assessment and should be the first-line approach whenever possible[44] and self-report measures are applicable even in case of moderate dementia [45]. Considering the limited functional abilities of institutional residents, we used a 5-point verbal rating scale to assess their pain instead of traditional visual analogous scale (VAS), which is more difficult to use in clinical practice [46]. Pain identification remains a challenge in institutions, especially in older residents with dementia and at least one chronic disease. Our results showed that even this simpler pain scale may underestimate pain experience by older individuals with moderate to severe cognitive impairment and those with functional dependence. To effectively assess pain in this vulnerable population, we need to pay more attention on pain assessment using more assessment tools and encourage interdisciplinary collaboration. The UK National Guideline recommends using numerical rating scale or verbal descriptors for elderly individuals with mild to moderate cognitive decline. However, for cases with severe cognitive impairment, PAINAD (Pain in Advanced Dementia) and Doloplus-2 scale are recommended [45]. Youjeong et al. have suggested that further studies are needed to assess pain in older adults, and multidimensional tools may be required for accurate self-reporting of pain [47]. This approach can help uncover undiagnosed pain and improve the overall management of pain in this population.

Functional deficits are common among institutional residents, and the decline in physical function may increase the risk of mortality and adverse health outcomes [48, 49]. In our study, most of the residents showed high dependency in ADL and IADL (mean scores: 24.9 ± 31.8 and 0.98 ± 1.62, respectively). A recent study reported that pain significantly predicted a decline in ADL functioning over a 6-month follow-up in order individuals with limited ability to communicate, as determined using a pain assessment checklist (PACSLAC-D) [50]. A cross-sectional study including community-dwelling older adults showed a positive association between pain and functional impairment in participants with cognitive impairment (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.15,2.62; p < 0.01). However, a systematic review of 11 studies revealed controversial results in eight of the studies and showed no or weak association between pain and functional impairment. Therefore, we investigated the relationship between pain report and functional deficits in institutional older residents. We observed that the presence of pain showed a significant association with IADL, but not ADL. Other contributing factors may have affected the association between pain and functioning in our study population, in which most residents had cognitive impairment. Basic ADLs comprise daily fundamental skills, whereas IADLs require a more complex capacity to live independently in a community. Declined performance in IADLs is observed in the early stages of dementia, whereas impairments in ADL are often noted in later stages of dementia[38]. In our study, residents with reported pain had a higher IADL level than those without pain (1.04 ± 1.61 and 0.94 ± 1.62, respectively). The residents who were capable of understanding tasks and questions in the questionnaire and express their pain well were considered as having IADL function.

Pain assessment in institutional residents is a complex task that requires more comprehensive and reliable tools to accurately detect pain in. Previous systemic review studies have highlighted the importance of identifying of barriers and facilitators to pain assessment in improving the quality of care provided for nursing home residents [51, 52]. While standard pain assessment tools are still lacking, other reliable assessment tools have been developed and studied for their application in individuals with dementia [53, 54]. However, a recent meta-analysis has shown that the routine use of a pain tool alone is insufficient to evaluate pain experience by patients with dementia and that a comprehensive pain model involving multidisciplinary health professionals is necessary to improve pain management [55]. Supplementary assessment tools such as observational ratings for pain-related behaviors by observers (body movement, facial expression, and vocalization domain) [41, 56,57,58] and electronic pain recognition tools have also been suggested to aid in pain assessment [59, 60]. Further research is needed to develop and validate more comprehensive pain assessment tools to improve pain management in this vulnerable population.

The strength of our study lies in its large sample size and highly representative nature. However, this study still has some limitations. A previous study reported that the EQ-5D as a self-report tool is suitable for use in older nursing home residents with cognitive impairment, whereas the validity of the EQ VAS was lower [61]. Although we used a simpler 5-point verbal descriptor pain scale with numbers to examine different pain intensities, this tool may have still not reflected the actual extent of pain experienced by the residents as pain is a complex phenomenon and can be more difficult to evaluate in the older population. We plan to incorporate multidimensional pain assessment tools as the next step in our study, particularly to assess pain among residents with multiple health issues. Furthermore, the characteristics, duration and locations of pain as well as current medications that the residents were taking to alleviate pain were not evaluated in this study. More studies that incorporate the aforementioned aspects are warranted in the future.

Conclusions

Unmanaged pain is common among the institutional residents in Taiwan. Painful conditions impact on functional dependence (IADL), emotional/behavioral problems and quality of life. Patients with a certain degree of cognitive impairment often underestimate their painful conditions, which may subsequently lead to devastating health consequences. Thus, more attention and focus must be given to the evaluation of the pain conditions in this vulnerable population.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activities of daily living

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- CDR:

-

Clinical dementia rating scale

- IADL:

-

Instrumental activities of daily living

- VAS:

-

Visual analogous scale

References

Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, Keefe FJ, Mogil JS, Ringkamp M, Sluka KA, Song XJ, Stevens B, Sullivan MD, Tutelman PR, Ushida T, Vader K. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976–82.

Jones MR, Ehrhardt KP, Ripoll JG, Sharma B, Padnos IW, Kaye RJ, Kaye AD. Pain in the Elderly. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(4):23.

International Pain Summit Of The International Association For The Study Of Pain. Declaration of Montreal: declaration that access to pain management is a fundamental human right. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25(1):29–31.

Won AB, Lapane KL, Vallow S, Schein J, Morris JN, Lipsitz LA. Persistent nonmalignant pain and analgesic prescribing patterns in elderly nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(6):867–74.

Cravello L, Di Santo S, Varrassi G, Benincasa D, Marchettini P, de Tommaso M, Shofany J, Assogna F, Perotta D, Palmer K, Paladini A, di Iulio F, Caltagirone C. Chronic Pain in the Elderly with Cognitive Decline: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther. 2019;8(1):53–65.

Hunnicutt JN, Ulbricht CM, Tjia J, Lapane KL. Pain and pharmacologic pain management in long-stay nursing home residents. Pain. 2017;158(6):1091–9.

Harris-Kojetin L, Sengupta M, Park-Lee E, Valverde R, Caffrey C, Rome V, Lendon J. Long-Term Care Providers and services users in the United States: data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013-2014. Vital Health Stat 3. 2016;(38):x–xii; 1–105. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27023287/.

Chen CF, Fu TH. Policies and Transformation of Long-Term Care System in Taiwan. Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2020;24(3):187–94.

AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6 Suppl):S205-24.

Gloth FM 3rd. Geriatric pain. Factors that limit pain relief and increase complications. Geriatrics. 2000;55(10):46–8 51–4.

Bernabei R, Gambassi G, Lapane K, Landi F, Gatsonis C, Dunlop R, Lipsitz L, Steel K, Mor V. Management of pain in elderly patients with cancer. SAGE Study Group. Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use via Epidemiology. JAMA. 1998;279(23):1877–82.

Borsook D. Neurological diseases and pain. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 2):320–44.

Klit H, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. Central post-stroke pain: clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(9):857–68.

Hoffmann F, Kaduszkiewicz H, Glaeske G, van den Bussche H, Koller D. Prevalence of dementia in nursing home and community-dwelling older adults in Germany. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2014;26(5):555–9.

Kao YH, Hsu CC, Yang YH. A Nationwide Survey of Dementia Prevalence in Long-Term Care Facilities in Taiwan. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1554.

Hsieh SW, Huang LC, Hsieh TJ, Lin CF, Hsu CC, Yang YH. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in institutional residents with dementia in Taiwan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2021;21(8):718–24.

Collaborators GBDDF. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(2):e105–25.

Meng L, Zhao J, Liu J, Li S. Cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive impairment. Journal of Neurorestoratoratology. 2019;7(4):184–95.

Yang Y, Fuh J, Mok VCT. Vascular Contribution to Cognition in Stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain Science Advances. 2018;4(1):39–48.

Proctor WR, Hirdes JP. Pain and cognitive status among nursing home residents in Canada. Pain Res Manag. 2001;6(3):119–25.

Sawyer P, Lillis JP, Bodner EV, Allman RM. Substantial daily pain among nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2007;8(3):158–65.

Hirase T, Kataoka H, Nakano J, Inokuchi S, Sakamoto J, Okita M. Impact of frailty on chronic pain, activities of daily living and physical activity in community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(7):1079–84.

Duenas M, Salazar A, de Sola H, Failde I. Limitations in Activities of Daily Living in People With Chronic Pain: Identification of Groups Using Clusters Analysis. Pain Pract. 2020;20(2):179–87.

Stamm TA, Pieber K, Crevenna R, Dorner TE. Impairment in the activities of daily living in older adults with and without osteoporosis, osteoarthritis and chronic back pain: a secondary analysis of population-based health survey data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:139.

Shega JW, Ersek M, Herr K, Paice JA, Rockwood K, Weiner DK, Dale W. The multidimensional experience of noncancer pain: does cognitive status matter? Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1680–7.

Stolee P, Hillier LM, Esbaugh J, Bol N, McKellar L, Gauthier N. Instruments for the assessment of pain in older persons with cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):319–26.

Pautex S, Herrmann F, Le Lous P, Fabjan M, Michel JP, Gold G. Feasibility and reliability of four pain self-assessment scales and correlation with an observational rating scale in hospitalized elderly demented patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(4):524–9.

Taylor LJ, Harris J, Epps CD, Herr K. Psychometric evaluation of selected pain intensity scales for use with cognitively impaired and cognitively intact older adults. Rehabil Nurs. 2005;30(2):55–61.

Weiner DK, Peterson BL, Logue P, Keefe FJ. Predictors of pain self-report in nursing home residents. Aging (Milano). 1998;10(5):411–20.

Chireh B, D’Arcy C. Pain and self-rated health among middle-aged and older Canadians: an analysis of the Canadian community health survey-healthy aging. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1006.

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386–91.

O’Bryant SE, Humphreys JD, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, Lucas JA. Detecting dementia with the mini-mental state examination in highly educated individuals. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(7):963–7.

Creavin ST, Wisniewski S, Noel-Storr AH, Trevelyan CM, Hampton T, Rayment D, Thom VM, Nash KJ, Elhamoui H, Milligan R, Patel AS, Tsivos DV, Wing T, Phillips E, Kellman SM, Shackleton HL, Singleton GF, Neale BE, Watton ME, Cullum S. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the detection of dementia in clinically unevaluated people aged 65 and over in community and primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(1):CD011145.

Castro-Costa E, Fuzikawa C, Uchoa E, Firmo JO, Lima-Costa MF. Norms for the mini-mental state examination: adjustment of the cut-off point in population-based studies (evidences from the Bambui health aging study). Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2008;66(3A):524–8.

Scazufca M, Almeida OP, Vallada HP, Tasse WA, Menezes PR. Limitations of the Mini-Mental State Examination for screening dementia in a community with low socioeconomic status: results from the Sao Paulo Ageing & Health Study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(1):8–15.

Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9 Suppl 1:173–6 discussion 177–8.

Noelker LS, Browdie R. Sidney Katz, MD: a new paradigm for chronic illness and long-term care. Gerontologist. 2014;54(1):13–20.

Mlinac ME, Feng MC. Assessment of Activities of Daily Living, Self-Care, and Independence. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2016;31(6):506–16.

Cheung PWH, Wong CKH, Samartzis D, Luk KDK, Lam CLK, Cheung KMC, Cheung JPY. Psychometric validation of the EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) in Chinese patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2016;11:19.

Lin HW, Li CI, Lin FJ, Chang JY, Gau CS, Luo N, Pickard AS, Ramos Goni JM, Tang CH, Hsu CN. Valuation of the EQ-5D-5L in Taiwan. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12): e0209344.

Zwakhalen SM, Hamers JP, Abu-Saad HH, Berger MP. Pain in elderly people with severe dementia: a systematic review of behavioural pain assessment tools. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:3.

Atee M, Morris T, Macfarlane S, Cunningham C. Pain in Dementia: Prevalence and Association With Neuropsychiatric Behaviors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(6):1215–26.

Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M, Staniland A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Aarsland D, Ballard C. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(5):264–74.

Chow S, Chow R, Lam M, Rowbottom L, Hollenberg D, Friesen E, Nadalini O, Lam H, DeAngelis C, Herrmann N. Pain assessment tools for older adults with dementia in long-term care facilities: a systematic review. Neurodegener Dis Manag. 2016;6(6):525–38.

Schofield P. The Assessment of Pain in Older People: UK National Guidelines. Age Ageing. 2018;47(suppl_1):i1–22.

Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14(7):798–804.

Kang Y, Demiris G. Self-report pain assessment tools for cognitively intact older adults: Integrative review. Int J Older People Nurs. 2018;13(2): e12170.

Ramos LR, Simoes EJ, Albert MS. Dependence in activities of daily living and cognitive impairment strongly predicted mortality in older urban residents in Brazil: a 2-year follow-up. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(9):1168–75.

Millan-Calenti JC, Tubio J, Pita-Fernandez S, Gonzalez-Abraldes I, Lorenzo T, Fernandez-Arruty T, Maseda A. Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(3):306–10.

van Dalen-Kok AH, Pieper MJC, de Waal MWM, van der Steen JT, Scherder EJA, Achterberg WP. The impact of pain on the course of ADL functioning in patients with dementia. Age Ageing. 2021;50(3):906–13.

Dirk K, Rachor GS, Knopp-Sihota JA. Pain Assessment for Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review Protocol. Nurs Res. 2019;68(4):324–8.

Knopp-Sihota JA, Dirk KL, Rachor GS. Factors Associated With Pain Assessment for Nursing Home Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Synthesis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(7):884-892 e3.

Ammaturo DA, Hadjistavropoulos T, Williams J. Pain in Dementia: Use of Observational Pain Assessment Tools by People Who Are Not Health Professionals. Pain Med. 2017;18(10):1895–907.

Ersek M, Neradilek MB, Herr K, Hilgeman MM, Nash P, Polissar N, Nelson FX. Psychometric Evaluation of a Pain Intensity Measure for Persons with Dementia. Pain Med. 2019;20(6):1093–104.

Tsai YI, Browne G, Inder KJ. The effectiveness of interventions to improve pain assessment and management in people living with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analyses. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(3):1127–40.

Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2003;4(1):9–15.

Corbett A, Achterberg W, Husebo B, Lobbezoo F, de Vet H, Kunz M, Strand L, Constantinou M, Tudose C, Kappesser J, de Waal M, Lautenbacher S, EU-COST action td 1005 Pain Assessment in Patients with Impaired Cognition, especially Dementia Collaborators. An international road map to improve pain assessment in people with impaired cognition: the development of the Pain Assessment in Impaired Cognition (PAIC) meta-tool. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:229.

van Dalen-Kok AH, Achterberg WP, Rijkmans WE, de Vet HC, de Waal MW. Pain assessment in impaired cognition: observer agreement in a long-term care setting in patients with dementia. Pain Manag. 2019;9(5):461–73.

Atee M, Hoti K, Parsons R, Hughes JD. Pain Assessment in Dementia: Evaluation of a Point-of-Care Technological Solution. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;60(1):137–50.

Atee M, Hoti K, Hughes JD. Psychometric Evaluation of the Electronic Pain Assessment Tool: An Innovative Instrument for Individuals with Moderate-to-Severe Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2017;44(5–6):256–67.

Perez-Ros P, Martinez-Arnau FM. EQ-5D-3L for Assessing Quality of Life in Older Nursing Home Residents with Cognitive Impairment. Life (Basel). 2020;10(7):100.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW), Taiwan; National Health Research Institutes (NHRI) (07D1-FRMOHW04), Taiwan; the Neuroscience Research Center and Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University (KMU-TC110B03, KMTTH-DK(C)110008), Taiwan. The authors thank Miss Chung-Fen Lin of the NHRI for her dedicated statistical analysis. We also sincerely thank each of our partners for their great contributions, including the professional committee invited by the MOHW, the trained raters, neurologists or geriatric psychiatrists, members of Taiwan Dementia Society (TDS), institutional administrators and staff, local government for each site, and everyone contributing to the study. This article is the report of collective result of dementia researchers in Taiwan.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. Other supporters include Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST110-2314-B-037–092, NSTC 112-2314-B-037-124), Kaohsiung Municipal Ta-Tung Hospital (kmtth-111–005, 111-TA-03), Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center Grant (KMU-TC110B03), National health Research Institutes (07D1-FRMOHW04). The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: C.C.H., S.H.W., and Y.H.Y. Acquisition of data: C.F.L. and M.S.Y. Analysis and interpretation of data: S.H.W., C.F.L. and Y.H.Y. Drafting of the manuscript: S.H.W. Critical revision: S.H.W., I.C.L. and Y.H.Y. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Research Ethics Committee of National Health Research Institute (EC1080502). Written informed consent was obtained for all participants in the study after having been informed about the study. Informed consent statement for those with self-determination was impossible, proxy was requested for their families. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations by including a statement in the ethics approval and consent to participate section.

Consent for publication

Not applicate.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplemental Table 1.

Association between comorbidities and pain for those with dementia. Supplemental Table 2. Association between ADL, IADL, Mood, Quality of Life and pain for those with dementia. Supplemental Table 3. Association between comorbidities and pain for those without dementia. Supplemental Table 4. Association between ADL, IADL, Mood, Quality of Life and pain for those without dementia

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, SH., Lin, CF., Lu, IC. et al. Association between pain and cognitive and daily functional impairment in older institutional residents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 23, 756 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04337-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04337-8