Abstract

Background

The effects of statins on the reduction of mortality in individuals aged 75 years or older remain controversial. We conducted this study to investigate whether there is an association between statin therapy and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) who are over the age of 75 years.

Methods

The present study used data from the Staged Diabetes Targeting Management Study, which began in 2005. A total of 518 T2DM patients older than 75 years were included. Cox regression analyses were used to evaluate the association between statins and specific causes of death in patients with T2DM.

Results

After a follow-up period of 6.09 years (interquartile range 3.94–8.81 years), 111 out of 518 patients died. The results of Cox regression analyses showed that there was no significant association between statin use and all-cause mortality (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.47, 1.19) after adjustment for all potential confounders. Subgroup analysis indicated that statins had no association with the risk of all-cause mortality or deaths caused by ischemic cardiovascular diseases in T2DM patients with or without coronary heart disease.

Conclusions

Our study found no significant association between all-cause mortality and statin use in T2DM patients over the age of 75 years. More evidence is needed to support the use of statins in the elderly T2DM patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases (ASCVD) are the leading cause of death in most parts of the world [1, 2], with coronary heart disease (CHD) and ischemic stroke (IS) accounting for 42% and 35% of global cardiovascular mortality, respectively [2]. Statins are first-line evidence-based drugs for the management of dyslipidemia and for secondary prevention of ASCVD events across age groups [3, 4]. A number of studies have demonstrated that in addition to its cholesterol lowering effect, statins also show pleiotropic effects such as modulating immune responses, and inhibiting subclinical inflammation and oxidative stresses [5, 6]. In addition, the benefits of statins for primary prevention in subjects under 75 years old have been well established based on multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs), except for those over 75 years of age [7,8,9,10].

The advantage of statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality in patients over 75 years old remains controversial, mainly because there is significantly less evidence for this age group and the risk for statin-related harms increases with age, which could potentially offset their positive effects [11,12,13,14,15]. Most of the available evidence regarding statin use for primary prevention of ASCVD in these patients is derived from subgroup analyses of RCTs. However, the US Preventive Services Task Force concluded in a recent review that older people are underrepresented in trials and there is insufficient evidence to draw a robust conclusion about the balance between benefits and harms of statins for primary prevention in this age group [11, 12]. Recently, it was revealed by an individual participant data meta-analysis including 28 RCTs that statin therapy resulted in a significant reduction of major vascular events irrespective of age, but there is less evidence of benefit among participants older than 75 years without previous vascular diseases (primary prevention) [15]. Consistently, two recently published real-world retrospective studies also found that use of statins was not associated with a lower risk of outcomes including all-cause death in the primary prevention among individuals without diabetes or other modifiable risk factors [13, 14].

It was well known that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have a similar risk of ASCVD to those with a history of cardiovascular disease [16]. Interestingly, statin use was significantly associated with reduced incident ASCVD and all cause mortality in diabetic patients without clinically recognized ASCVD in Spanish population [13]. Against this background, we undertook this study to investigate whether there is an association between statin therapy and mortality in patients with T2DM over the age of 75 years in Chinese population.

Methods

Patients

The present study was conducted using the data taken from the Staged Diabetes Targeting Management (SDTM) Study [17, 18], which was started since 2005 as a continuous structured diabetes care program in Jiangsu Province Official Hospital. All patients were managed according to the Staged Diabetes Management protocol adopted from International Diabetes Center (Minneapolis, US) [19], and the information of each visit was recorded online (www.chinasdtm.com). The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethical Committee, Jiangsu Province Official Hospital, Nanjing. Informed consent was obtained from all patients at the time of first assessment to allow use of their data for research purposes.

Clinical and laboratory data

The information recorded in the SDTM study has been described [20, 21]. Briefly, body weight, height and blood pressure were measured by the diabetic specialist nurses according to standard protocols. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the ratio of the weight (kg) to squared height (m2). Details on personal information, history of disease and current use of medications were also obtained from all patients through interviews by the nurses. Blood tests were carried out after an overnight fasting for glucose, lipid profiles, uric acid (UA), renal/liver functions and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). Glucose, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and serum creatinine (Scr) were measured using Hitach 7060 automated analyzer (Hitachi Koki Co. Ltd., Hitachinaka City, Japan). HbA1c was measured by Bio-rad Diamat high-performance liquid chromatography analyzer (Bio-Rad Labs., Brea, CA, USA). Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation [22].

Outcomes

The incident endpoint events of all-cause mortality and the causes of death including ischemic cardiovascular diseases (CHD and IS), cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease (CCVD) (including IS, CHD and hemorrhagic stroke (HS)), cancer, respiratory system disease and renal failure were collected from the SDTM database. In addition, telephone-interviews were performed by diabetic specialist nurses to confirm the status of 518 participants in January 2018. Finally, all the mortality data were further verified through the resident database from local centers for disease control system as well.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS (version 20.0) software. Variables were assessed for the full cohort and stratified by statin use. All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or percentage, where appropriate. Unpaired student’s t-test was used to compare differences between two groups. Rates were compared using the χ 2 test. The effect of statins on all-cause mortality, and deaths caused by ischemic cardiovascular disease, HS, cancer, respiratory system disease and renal failure were analyzed and in subgroups stratified by the presence or absence of prior CHD. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) by Cox regression were used to estimate the association between statins and specific death of T2DM. Variables those were significant in univariable analyses and had biological plausibility were entered into multivariate Cox regression models.

Results

Characteristics of study population

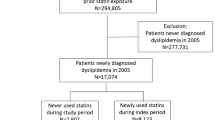

A total of 4285 diabetic patients were enrolled in the SDTM study until January 2018. After excluding those who younger than 75 years at baseline (N = 3524), loss to follow-up (N = 195), had a history of type 1 diabetes, glutamic acid decarboxylase positive or impaired glucose regulation at baseline (N = 19), missing data for key variables (N = 29), we had the complete data of 518 patients with T2DM for the final analysis (Fig. 1). Characteristics of participants included in and excluded from the study were shown in Table S1.

Of the 518 participants, there were 307 (59.27%) men and 211 (40.73%) women, with a mean age of 79.82 ± 3.50 years. The clinical and metabolic characteristics of the subjects grouped by the use of statins were shown in Table 1. Generally, the subjects using statins have higher levels of BMI, systolic blood pressure (SBP), fasting blood glucose (FBG), postprandial blood glucose (PBG), HbA1c levels, and lower hemoglobin (Hb) levels (Table 1).

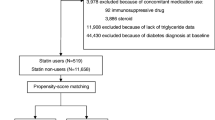

Furthermore, we performed propensity score matching (PSM) model by key variables at baseline, including sex, age, BMI, SBP, Hb, HbA1c, HDL-C, CHD, HT, calcium channel blocker, angiotensin receptor blocker, sulfonylureas, insulin, metformin, beta blockers. After PSM, 116 pairs of participants were included. There were no difference of variables between groups (Table 1).

Characteristics of population with different outcomes

The median follow-up period was 6.09 years (interquartile range 3.94–8.81 years). During the follow-up, 111 patients died, including 23 caused by ischemic cardiovascular disease, 27 by CCVD, 21 by cancer, 15 by respiratory system disease, 6 by renal failure and 19 by other conditions. As shown in Table 2, age, microalbuminuria, PBG, and UA showed higher levels in the group of patients who died, while HDL-C and eGFR showed lower levels.

Association of statin use and all-cause mortality and specific mortality

There was no statistical association between statin use and all-cause mortality (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.47, 1.19) and CCVD (HR 0.49; 95% CI 0.18, 1.32) after adjustment for all potential confounders including baseline age, sex, BMI, Hb, HbA1c, medical history and medications. Statin use was associated with reduced ischemic cardiovascular disease mortality (HR 0.31; 95% CI 0.10, 0.97). However, after PSM, Cox regression analyses showed that statin use was not associated with all-caused mortality, ischemic cardiovascular disease mortality and CCVD mortality (Table 3).

Subgroup analysis indicated that statins had no association with the all-caused mortality or mortality caused by ischemic cardiovascular disease in T2DM patients without CHD, HRs (95% CIs) were 0.59 (0.33, 1.03) and 0.31 (0.09, 1.06), respectively.In T2DM patients with CHD, statins had no association with all-caused mortality [1.79 (0.62, 5.20)], neither (Table 4). Similar results were also shown by cox regression analyses in matched pairs.

Discussions

Our findings explored issues that have remained controversial and insufficiently studied to date. In our cohort study of 518 T2DM patients over 75 years old, the results indicated a nonsignificant association of reduced all-caused mortality and ischemic cardiovascular disease with the statin use. To our knowledge, this is the first time to raise the possibility of statins associated with a reduction in mortality in elderly individuals in the Chinese population.

The potential benefits of statins for primary prevention of mortality in the elderly remain controversial. A subanalysis of the JUPITER study found no benefits of statins in reducing mortality for individuals aged > 70 years [23]. Similarly, in the PROSPER study that focused on primary prevention in elderly individuals, pravastatin was found to have no benefits for all-cause mortality [24]. Meta-analyses also suggested that statins do not have a protective effect against all-cause mortality for individuals aged over 65 years old in the setting of primary prevention [25, 26]. However, a nonsignificant direction toward increased all-cause mortality with pravastatin was observed among adults 75 years and older in the ALLHAT-LLT study [27].

In contrast, statins are associated with reduced mortality in aged 75 and older population in some other studies. In the US veterans study with patients 75 years and older and free of ASCVD at baseline, prescription of statins for the first time was significantly associated with a lower risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [28]. The SCOPE-75 study suggested a remarkable reduction in the relative risk of all-cause death among statin users aged over 75 years for primary prevention [29]. The Reykjavik Study, which enrolled subjects with a mean age of 77 years, reported a greater benefit of statins in the subgroup of diabetic subjects [30]. Moreover, in a large-scale retrospective cohort study with 46, 864 people aged 75 years or more without cardiovascular diseases, Rafel Ramos and colleagues also revealed that statin use was significantly associated with reduced all-cause mortality in diabetic patients for primary prevention [13]. In fact, Rafel et al. found that the protective effect of statins against all-cause mortality in participants with diabetes became weaker as age increased and began to lose statistical significance at age 82 years [13].

Our findings appear to be consistent with these studies in elderly T2DM patients. In our population, statin use showed a reduction association with ischemic cardiovascular disease mortality, although it does not reach statistical significance after PSM. Age should be considered as an important factor affecting the protective effects of statins. It is worth noting that the average age in our study is about 80 years. Meanwhile, relatively small sample size may also responsible for the lack of effect observed.

The majority of published data suggest that statin usage does not affect the incidence of most cancers [31]. Our present study, in accordance with previous studies, demonstrates that the associations between statin use and cancer-related outcomes were not statistically significant. Similarly, non-vascular death, deaths caused by respiratory system disease and renal failure were not affected by statin use in the present study or in most previous studies.

There are several limitations in this study. It was carried out in a cohort that only comprised Chinese T2DM patients managed at a single outpatient clinic in Nanjing with a relative small sample size. There may be potential bias between different groups due to the observational study design, although we conducted PSM. More studies, especially prospective studies with large sample size and RCTs, are needed to confirm our finding. In addition, the proportion of patients who used low- or high-intensity statins was too small to investigate the possibility of different clinical outcomes between these groups. Despite these limitations, these real-world data recorded most of potential confounding factors, which might strengthen the findings of the present study. Moreover, the relatively long follow-up period (about 6.09 years) may provide a more accurate view of the effects of statin use on long-term mortality.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that statin use showed a possible reduction in all-cause mortality and ischemic cardiovascular disease mortality, although it does not reach statistical significance. More evidence is needed to support the use of statins in the elderly T2DM patients.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASCVD:

-

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- IS:

-

Ischemic stroke

- RCTs:

-

Randomized clinical trials

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- SDTM:

-

Staged Diabetes Targeting Management

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- UA:

-

Uric acid

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglycerides

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- Scr:

-

Serum creatinine

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- CCVD:

-

Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease

- HS:

-

Hemorrhagic stroke

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- PBG:

-

Postprandial blood glucose

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- PSM:

-

Propensity score match

References

Marrugat J, Sala J, Manresa JM, Gil M, Elosua R, Perez G, et al. Acute myocardial infarction population incidence and in-hospital management factors associated to 28-day case-fatality in the 65 year and older. Eur J Epidemiol. 2004;19(3):231–7.

Collaborators GBDCoD. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–210.

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–78.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C, Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9976):1397–405.

Oesterle A, Laufs U, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of statins on the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2017;120(1):229–43.

Endres M. Statins: potential new indications in inflammatory conditions. Atheroscler Suppl. 2006;7(1):31–5.

Yandrapalli S, Gupta S, Andries G, Cooper HA, Aronow WS. Drug therapy of dyslipidemia in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2019;36(4):321–40.

Mortensen MB, Falk E. Primary prevention with statins in the elderly. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(1):85–94.

Ruscica M, Macchi C, Pavanello C, Corsini A, Sahebkar A, Sirtori CR. Appropriateness of statin prescription in the elderly. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;50:33–40.

Singh S, Zieman S, Go AS, Fortmann SP, Wenger NK, Fleg JL, et al. Statins for primary prevention in older adults-moving toward evidence-based decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(11):2188–96.

Konrat C, Boutron I, Trinquart L, Auleley GR, Ricordeau P, Ravaud P. Underrepresentation of elderly people in randomised controlled trials. The example of trials of 4 widely prescribed drugs. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e33559.

Force USPST, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, et al. Statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults: us preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2016;316(19):1997–2007.

Ramos R, Comas-Cufi M, Marti-Lluch R, Ballo E, Ponjoan A, Alves-Cabratosa L, et al. Statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular events and mortality in old and very old adults with and without type 2 diabetes: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:k3359.

Bezin J, Moore N, Mansiaux Y, Steg PG, Pariente A. Real-life benefits of statins for cardiovascular prevention in elderly subjects: a population-based cohort study. Am J Med. 2019;132(6):740–740-8 e7.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in older people: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from 28 randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):407–15.

Rana JS, Liu JY, Moffet HH, Jaffe M, Karter AJ. Diabetes and prior coronary heart disease are not necessarily risk equivalent for future coronary heart disease events. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(4):387–93.

Ouyang XMY, Bian R, et al. Improving glycemic control in T2DM patients: Implementation of staged diabetes targeting management. Chin J Diabetes. 2013;21:55–9.

Bi Y, Liu L, Lu Y, Sun T, Shen C, Chen X, et al. T7 peptide-functionalized PEG-PLGA micelles loading with carmustine for targeting therapy of glioma. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:27465–73.

Mazze RS, Etzwiler DD, Strock E, Peterson K, McClave CR 2nd, Meszaros JF, et al. Staged diabetes management. Toward an integrated model of diabetes care. Diabetes Care. 1994;17(Suppl 1):56–66.

Li M, Gu L, Yang J, Lou Q. Serum uric acid to creatinine ratio correlates with beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34(5):e3001.

Gu L, Huang L, Wu H, Lou Q, Bian R. Serum uric acid to creatinine ratio: a predictor of incident chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with preserved kidney function. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2017;14(3):221–5.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12.

Glynn RJ, Koenig W, Nordestgaard BG, Shepherd J, Ridker PM. Rosuvastatin for primary prevention in older persons with elevated C-reactive protein and low to average low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: exploratory analysis of a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(8):488–96, W174.

Shepherd J, Blauw GJ, Murphy MB, Bollen EL, Buckley BM, Cobbe SM, et al. Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9346):1623–30.

Savarese G, Gotto AM Jr, Paolillo S, D’Amore C, Losco T, Musella F, et al. Benefits of statins in elderly subjects without established cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(22):2090–9.

Teng M, Lin L, Zhao YJ, Khoo AL, Davis BR, Yong QW, et al. Statins for Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Elderly Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(8):649–61.

Han BH, Sutin D, Williamson JD, Davis BR, Piller LB, Pervin H, et al. Effect of statin treatment vs usual care on primary cardiovascular prevention among older adults: the ALLHAT-LLT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):955–65.

Orkaby AR, Driver JA, Ho YL, Lu B, Costa L, Honerlaw J, et al. Association of statin use with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US veterans 75 years and older. JAMA. 2020;324(1):68–78.

Kim K, Lee CJ, Shim CY, Kim JS, Kim BK, Park S, et al. Statin and clinical outcomes of primary prevention in individuals aged >75years: The SCOPE-75 study. Atherosclerosis. 2019;284:31–6.

Olafsdottir E, Aspelund T, Sigurdsson G, Thorsson B, Eiriksdottir G, Harris TB, et al. Effects of statin medication on mortality risk associated with type 2 diabetes in older persons: the population-based AGES-Reykjavik Study. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1):e000132.

Beckwitt CH, Brufsky A, Oltvai ZN, Wells A. Statin drugs to reduce breast cancer recurrence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):144.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was supported by 2018III-2205 from the “333” Project of Jiangsu Province, and NMUB2019256 from science and technology development fund of Nanjing medical university. The Funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. J.W. verified the data. H.D-W and L.L-D performed clinical observation. L.W. and L.B-G conceived this study and critically revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to interpreting the findings and the development of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the Ethical Committee, Jiangsu Province Institute of Geriatrics, Nanjing ((2020) Institution Ethical Review Document No. 020). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients at the time of first assessment to allow use of their data for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics of participants included in and excluded from study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, Y., Wang, J., Wu, H. et al. Effect of statin treatment on mortality in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr 23, 549 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04252-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04252-y