Abstract

Background

The causes and consequences of social isolation and loneliness of older people living in rural contexts during the COVID-19 pandemic were systematically reviewed to describe patterns, causes and consequences.

Methods

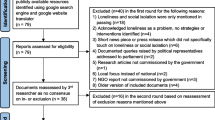

Using the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) scoping review method, searches were conducted between March and December 2022, 1013 articles were screened and 29 were identified for data extraction.

Results

Findings were summarized using thematic analysis separated into four major themes: prevalence of social isolation and loneliness; rural-only research; comparative urban-rural research; and technological and other interventions. Core factors for each of these themes describe the experiences of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic and related lockdowns. We observed that there are interrelationships and some contradictory findings among the themes.

Conclusions

Social isolation and loneliness are associated with a wide variety of health problems and challenges, highlighting the need for further research. This scoping review systematically identified several important insights into existing knowledge from the experiences of older people living in rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic, while pointing to pressing knowledge and policy gaps that can be addressed in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

First identified in late 2019, the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has resulted in a global pandemic, particularly affecting the lives of older adults owing to their higher likelihood of having pre-existing conditions or multimorbidity, and of being immune compromised [1,2,3,4]. It is a highly contagious viral disease that has been associated with a spectrum of deleterious health effects, ranging from flu-like symptoms to death. Older adults, particularly those in institutional settings such as long-term care facilities (LTC), have been the most affected by the serious complications of COVID-19 infection and have accounted for the highest percentage of deaths due to the virus [4, 5]. However, those living in the community have also experienced a higher risk of negative physical and mental health consequences [6, 7]. The high-risk of infection and its negative health consequences among older adults have prompted the use of the new term “geropandemic” among researchers [e.g., 8, 9]. Furthermore, media reports have heightened the awareness of these high-risk populations, which have in turn intensified feelings of vulnerability, fear, stress and anxiety. Public health policies to control the spread of the disease in many countries included “lockdowns,” where they restricted work environments or travel in and out of the country, closed schools, and limited overall mobility. These restrictive measures were deemed necessary to slow the COVID-19 transmission rates and to safeguard health institutions and resources from becoming overwhelmed by an unprecedented number of patients [10]. The subsequent isolation related to the lockdowns affected lives across geographic spaces at the global, regional, national and local levels [9]. The pandemic experiences and responses, including the effects of social isolation and loneliness, have been highly diverse depending on the level of urbanity or rurality level of environments [e.g., 11, 12]. These knowledge gaps have led to calls for reviews examining the effects of the pandemic on older adults living in rural environments [e.g., 13]. The present scoping review responded to these calls and aimed to analyze research studies that specifically examined the effects of social isolation and loneliness among older adults living in rural or remote communities.

Social isolation and loneliness

Social isolation and loneliness (Si/L) are increasingly deemed to be public health challenges with unique ageing associations. Social isolation has been typically defined, “as a lack in quantity and quality of social contacts” and “involves few social contacts and few social roles, as well as the absence of mutually rewarding relationships” [14, p.1]. Loneliness is usually defined as “a distressing feeling that accompanies the perception that one’s social needs are not being met by the quantity or especially the quality of one’s social relationships” [15, p.218]. In this paper, social isolation is defined as a separation from social connections, such as friends, family, acquaintances and loved ones. Loneliness, on the other hand, is defined as the subjective experience, often due to social isolation, but not necessarily. The terms can be mutually exclusive because it is possible to be separated from social contacts and not feel lonely, or to be in close contact with friends and family, but still experience feelings of loneliness [16]. The geography of the rural environment further complicates this separation of Si/L because residents are often simultaneously cast as at-risk in terms of health outcomes [e.g., 17–19], yet benefitting from higher levels of social cohesion activities (e.g., community participation, volunteering, etc.) as compared to urban areas [e.g., 20–23]. These nuanced understandings of one’s environment are important in determining how these experiences are recorded and measured by researchers. Social isolation is measured using quantitative measures of physical separation from an individual or network perspective. The subjective experience of loneliness is measured or understood based on quantitative scales or qualitative methods to capture individuals’ lived experiences. We do not review different conceptualizations and/or measurements of these concepts, but rather, focus on their patterns across rural-urban environments among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, given that the nexus of these factors is deemed to be relevant [24].

Research challenges studying rural environments, isolation and COVID-19

An important challenge for researchers conducting studies on rural environments is related to the definition of rural. Rurality is often given a residual definition, which defines it as what it is not (i.e., urban space), as opposed to what it is. The definition of urban areas often becomes the primary tool to determine what is and is not rural, but this differs greatly across studies and geographical context. For example, Canada defines urban centres as having a population of > 1000 and a population density of > 400 people per square kilometer [25]. Lower middle-income countries (LMICs) in the global periphery often lack clear, official definitions. Nigeria, for example, defines rural places as having a population < 20,000 and with a primary economic focus on agriculture, according to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs [26]. Our interest is centered on older adults who live in areas locally defined as “rural,” rather than attempt to impose a particular definition of “rurality” on the included studies. Despite the abundance of literature on ageing and rural environments, few studies have focused on this in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In many ways, social isolation is a de facto element of living in a rural environment as compared to an urban one, due to lower population density and physical distance between residences. Research has been equivocal in terms of levels and outcomes of social isolation and loneliness among older adults based on levels of rurality /urbanity of the environment. Henning-Smith and colleagues (2019) reported these equivocal findings based on a study of nearly 2,500 older adults living in rural, small towns and metropolitan urban centres [27]. The findings suggest that urban centre residents were more likely to feel socially isolated and lonely. However, significant differences existed among race and ethnicity divisions, and rural residents were found to be more at-risk for loneliness than their urban dwelling peers. Similar differences were found in differing measures of social contact, such as access to social services and social capital. For instance, research has established that older adults in rural environments are disadvantaged with respect to access to community and health services [e.g., 17–19, 28]. This association points to the issue of blurring between social and physical isolation. Yet, other research indicates that rural older adults have higher levels of social capital (i.e., stronger community connectedness), resulting in rich and more satisfying social engagement and support from neighbours and the broader community [e.g., 20–22]. Additionally, the role of technologies during Covid-19 to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults has been supported, although a focus on rural environments remains under-researched [29]. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has created increases in Si/L for most older adults due to public health behaviours and policies. Whether and to what degree rural older adults have experienced Si/L differentially than their counterparts in more urban environments is largely unknown.

Rationale for study

Despite the extensive literature addressing causes and consequences of Si/L among older adults spanning decades of research [see 30–34], systematic reviews of this knowledge in relation to the lived experiences in rural settings are few. Furthermore, a focus on the existing research conducted during the COVID-19 global pandemic represents a novel study and an organic experiment to study rural experiences of older adults under adverse conditions. Hence, we propose a scoping review to ask the following overarching question: what is known about the social isolation and loneliness of older adults living in rural settings during the COVID-19 pandemic? Our initial research questions include: (A) how did COVID-19 affect the prevalence of Si/L among older adults? (B) what factors contributed to Si/L among older adults during the pandemic? (C) how did Si/L affect the lives of older people during COVID-19; and (D) how were technological interventions employed to address Si/L among older adults during the pandemic? This review aims to synthesize the factors of the Si/L of older adults living in rural environments during the COVID-19 pandemic, describe the state of the existing literature, and identify key knowledge gaps systematically to facilitate subsequent research for further policy and program development.

Methods

Scoping reviews are a form of knowledge synthesis that aim to identify the key themes or concepts informing a particular area of research and summarize the main types of evidence and sources available based on a multi-step iterative process [35,36,37]. Scoping reviews are particularly useful when the literature on a topic has employed a range of data collection methods and/or analysis techniques, there is a lack of previous knowledge syntheses on the topic, and/or the project does not require a quality assessment of the included studies [35]. Our study topic meets all three criteria, which is why we have elected to employ the scoping review method. Our approach involves several procedural steps and the scoping review began in March 2022. The preliminary list of sources for inclusion was identified in December 2022, with the full article review having been completed in January 2023. We detail the procedural steps, derived using the scoping review method characterized by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), below [35].

Step 1 - identifying the question and relevant literature

We began by searching for existing reviews to determine the general knowledge and synthesis gaps relevant to our interest on how COVID-19 has affected older adults’ social lives in rural areas. Since no existing knowledge syntheses were found at the time of our scoping review, we refined our synthesis question to fill this knowledge gap. Following this, we devised a library data base search strategy to determine specific keywords specific to gerontological inquiry. In addition, we hand searched relevant titles and abstracts of recent studies to supplement the data search. Table 1 details our search strategy using identified keywords, which focused on four categories. After performing preliminary search attempts it was determined that some terms were responsible for erroneous returned results. The table was refined by utilising Boolean terms to better manage the returned search results employing an iterative process. For example, terms that further focused the search on the COVID-19 pandemic and those which limited or eliminated articles focusing on institutional care, were also identified and included at this stage. This process also helped to maintain a focus on rural areas due to the lack of institutional and long-term care provision in rural places.

Step 2 – searching the literature

A search strategy was used that included English-language, peer-reviewed literature published in scholarly journals, and our search strategy was developed to specifically target journals focusing on older adults and gerontology. These inclusion criteria were chosen for specific reasons, including: a lack of language ability outside of English on the review team; peer-reviewed articles published in quality journals maintains a high level of research incorporated into the review; and older adults were a criterion since a gerontological focus directed this study. Relevant combinations of keyword terms from Table 1 were searched in eight academic databases, including Google Scholar (Table 2). Boolean operators were used to maximize the combinations and permutations of the terms, and various combinations yielded marginally different results. Using an iterative process, additional keywords were added and Boolean terms and/or removed keywords when the returned results were irrelevant and/or unproductive.

Building on our consultations with the reference librarian, we used the gerontology-specific databases to conduct our search. We targeted Google Scholar for our preliminary database search used to identify exclusion terms. Certain terms, including nursing home and pandemic, consistently yielded unwanted results and were removed from subsequent searches by adding (-“nursing home”), (-“long-term care”), (-“senior center”), (-“HIV) and (-“AIDS”). Our preliminary Google Scholar searches indicated that this strategy would be unlikely to exclude potentially usable articles. Identical search queries were conducted in the database searches and were further focused using options within the ‘who’ category, as necessary. Some of the terms included within the “who” category are considered to be examples of ageist language (i.e., seniors); however, we decided to include these terms to maximize our search results. Search results were then organized and stored using Zotero reference management software and inputted into the Covidence review managing software and a shared Google Sheet.

Step 3 – charting the data

We used the Zotero software to remove duplicate sources. Our first step in data charting was to independently review the titles and abstracts to identify articles to be reviewed in full. Subsequently, the authors selected those that should be read in full for potential inclusion in the scoping review. Eliminated sources during the title/abstract review stage included (1) articles that lack focus on the synthesis question (e.g., social isolation, loneliness, COVID-19, and rural location), (2) materials that are not peer-reviewed published articles, and/or (3) sources not written in English.

Articles identified for full review were gathered through institutional journal subscriptions or inter-library loan. Two team members were assigned to read each article to determine if it should be included in the review. Authors independently reviewed articles remotely and recorded notes on the source and its viability for inclusion. The lead author reviewed the recommendations to reach consensus on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the scope of the extracted data. There were few initial disagreements related to inclusion or exclusion of the sources among the team members. In the few instances where consensus was not achieved between two readers, inclusion or exclusion was determined by a third reader to make the final determination. The main reasons for exclusion at this stage were a lack of clear focus on social and isolation and/or loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic, a lack of focus on older adults, or a distinction between rural- and urban-based older adults. During this step, we also hand-searched the reference lists of included articles to identify other sources that could undergo a second round of title and abstract review.

Step 4 - collating, summarizing and reporting the results

The review process was charted on the Covidence review managing software, and a secure, online spreadsheet editable by all team members and based on the authors’ previous experiences with scoping reviews [e.g., 29, 38]. We independently recorded bibliographic details of each study and extracted data for the reviewed articles. At the completion of the review phase, the extracted data were reviewed independently by each team member to identify themes and organise the findings relevant to the synthesis question. The lead author then inputted the included articles into QSR NVivo to code the data points and assist in the definition and identification of relevant themes. We then held remote correspondence to identify key themes and define their scope and scale. The following section details the four synthesis themes identified.

Findings

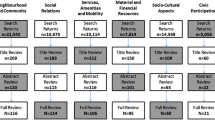

Figure 1 provides a summary of our scoping review search process and outcomes. Twenty-nine articles met the study criteria and were included in the review. Employing an inductive thematic analysis approach [39, 40], we followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) steps for thematic analysis: (i) familiarization, (ii) generation of codes, (iii) search and review themes, and (iv) theme definition. From the included articles we organized the review results according to the following four main crosscutting themes: (1) Prevalence of social isolation and loneliness, (2) Rural-only research (all participants lived in a rural environment with no comparison to non-rural group), (3) Urban-Rural comparative research, and (4) Technological and other interventions (see Table 3 with this organisation, and Table 4 for the methodological breakdown of the included studies). A further summary of all articles included for review can be found in Table 5. We further separate these results into positive or negative findings relating to each theme. While the prevalence and technological application themes align with the questions 1 & 4; we found it necessary to address research questions 2 & 3 in both rural-only and comparative thematic sections. The reason is based on methodological grounds, since the rural -only research is limited in generalizability; whereas the rural-urban comparative research has a benchmark against which we can contextualize the rural findings. We recognize that there is overlap exists among some of the themes. For example, seven studies were included in both the rural-only research and technology groups, while four studies were in both the comparative and technology groups. Table 5 also identifies the study design for each study, noting that the rural-only and technology groups were primarily qualitative, and the rural/urban comparative group was a mix of qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods.

Prevalence of social isolation/loneliness during the COVID-19 Pandemic (n = 10)

Positive outcomes for rural areas

Nine studies indicated that the prevalence of Si/L was less common in rural areas, compared to urban areas, with a primary focus on loneliness. These studies were conducted in five different countries, including Bangladesh [41, 42], Canada [43, 44], France [45], Serbia [46], the United States (US) [47], and the United Kingdom (UK) [48, 49]. Several studies determined rural areas to be a protective factor against Si/L, and identified women, those with financial challenges and additional chronic health issues, as groups with the highest prevalence or risk of loneliness [47,48,49]. Older rural residents in the US also had a lower prevalence of loneliness as compared to urban residents [47], and were much less worried about contracting COVID-19 [50]. The prevalence of loneliness was often connected to possible mental health issues, such as depression, and found to be similar to experiences of those in long-term care facilities [44, 46]. For example, Martin et al.’s (2022) study in rural Canada and found loneliness in 72% of respondents, with nearly 80% expressing concern for their mental health [44]. One study by Mistry et al. (2022a) conducted two periods of data collection in 2020 and 2021. In this study, the prevalence of loneliness was found to have dropped significantly from 2020 to 2021, which suggests some adaptation to the pandemic occurred in older, rural dwelling Bangladeshi adults [41].

Neutral outcomes for rural areas

Only two studies included for review found a neutral prevalence of loneliness in rural and urban places. These studies were conducted in Japan [51], and in the US [50]. Although limited in number, these studies suggest that rural areas are diverse and unique spaces with the potential to vary greatly. In the Japanese context, loneliness was prevalent, but rural or urban locations were found to be statistically insignificant when comparing levels of loneliness [51]. This study found that the prevalence of loneliness was quite high in rural and urban areas, even prior to the pandemic, and neighbourhood-based factors were likely the best protections against loneliness. Hennig-Smith et al. (2022b) found loneliness in the rural US to be prevalent in both urban and rural environments; however, the effect on mental health and social well-being outcomes for both rural and urban respondents was the same [50].

Rural-only research (n = 16)

Positive outcomes for rural places

In five of the sixteen rural-focused studies (i.e., based solely on rural participants), older adults were shown to be highly engaged socially in their daily lives and rural-dwelling older adults were more likely to report that they were supported [11, 12, 51, 53]. In fact, Colibaba et al. (2021) noted that older adults continued their practice of voluntarism to stay connected to the community during the pandemic and found the rural environment to be more suited to the lockdowns [52]. This was echoed by other studies, which found that older adults relied on past experiences of isolation to manage their mental health during the pandemic [11, 12]. Rural residents could go outside, in their gardens for example, without the fear of being in close contact with others [53]. The mechanisms contributing to protections against loneliness were quite varied amongst the studies. The most common reported activity that helped older adults maintain social connection during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns was volunteering [11, 12, 44, 52]. Volunteering acted to foster forms of support such as combating institutional changes (e.g., support for online learning and assistance with home schooling of children) and bridging gaps where existing infrastructure did not exist or was inadequate (e.g., the reallocation of transportation options when buses and taxis were not readily available) [11, 12, 52] found that the role of rural public libraries pivoted to create virtual meeting spaces for the local residents, including older adults [54].

Negative outcomes for rural places

Rural-only studies (n = 9) that found negative aspects linked to rural environments depicted a wide-range of environmental specific challenges, often for the most at-risk older adults. Older adults who were already experiencing Si/L prior to the pandemic and subsequent lockdowns became extremely isolated, and often lonely. This included those who were living alone [55], older adults with chronic health or substance abuse problems [44, 55], informal caregivers (i.e., often older adults providing spousal care) [43], and those who had recently moved to rural environments [56]. The lack of ability to connect with family, friends and routine social engagements caused significant mental health harm, often from a lack of rural-specific information and the fear surrounding COVID-19 infection and sickness [53, 57]. However, these challenges were identified in studies focused on populations in the Global North (i.e., more affluent, developed and powerful countries). 4 studies in the Global South (i.e., less affluent, underdeveloped countries) [58,59,60,61] exposed the precarious nature of ageing in rural places during the COVID-19 pandemic without official support infrastructure. In Nigeria, Ekoh et al. (2020, 2021, 2022) reported financial disaster for the rural-based older adults who depended entirely on familial support systems [58,59,60]. When these supports were disrupted by government mandated lockdowns, some older adults were left to starve with no way to travel to get food and no means to make purchases. In Ghana, similar depictions of the experience of older adults were made with a focus on those suffering from existing health issues, including blindness [61].

Rural/urban Comparative Articles (n = 10)

Positive outcomes for rural places

This theme was chosen based on methodological grounds, since comparative studies provide a benchmark against which rural findings can be contextualized. Six studies comparing rural and urban experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic identified protective factors of the rural environment for the Si/L of older adults [27, 45, 47,48,49, 62]. Peres et al. (2021) found that older rural residents were three times more likely to feel supported compared to urban dwellers, and further, that urban residents reporting twice the level of negative social experiences compared to their rural counterparts [45]. Rural environs are often close-knit communities, where rural residents are well connected and supportive of one another, which may be indicative of greater resilience to adversity in the form of social isolation [47]. Older rural residents often have family living close-by and were more likely to have visitors during the pandemic than their urban counterparts [45, 47, 49]. In Japan, older customs that are no longer relevant or active in urban areas were revived to help older residents stay connected. The revisiting of old customary ‘neighbourhood conferences’ (Osekkai) greatly reduced feelings of loneliness and helped build social connections [62].

Negative outcomes for rural places

Specific geographic characteristics of the rural environment, as compared to urban centres, were implicated in four studies as exacerbating experiences of loneliness and contributing to the deterioration of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly during lockdowns [42, 46, 56, 63]. Egeljić-Mihailović et al. (2022) found similar patterns of low social participation and depression symptoms in Serbia between those living in urban-based long-term care and those living in rural places [46]. Rural residents are heavily reliant on the few gathering spots available in their neighbourhoods and the loss of access to these places resulted in feelings of loss and loneliness [56]. Finlay et al. (2022) also found political differences in the US became more apparent when the social circles of older adults shrunk during the pandemic, particularly in rural areas [56]. The social challenges in rural contexts are further worsened by chronic health care issues and the lack of health care services as compared to urban environments [63]. Only one study included for review looked at the differences between urban and rural places and the experience of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. An urban/rural comparative study by Mistry and colleagues (2022b) found 53.4% of the rural-based participants to be lonely in 2020 compared to 43.7% of those in urban areas [42]. The key drivers of loneliness in this study were documented as financial strains and living alone in rural Bangladesh.

Technological and other interventions (n = 14)

Positive outcomes for rural places

The digital divide differentiates people and communities in access and use of Internet technology [64], which has been applied to older adults living in rural places [65,66,67]. However, the majority of studies (n = 8) included in this review exploring the connection between ageing, rurality and technology during the pandemic found many rural-dwelling older adults were actually early adopters of technologies to maintain social and familial contact. The digital technologies were wide ranging, with some being institutional driven and others being individual driven. Lenstra and colleagues (2022) found that US public libraries pivoted to virtual services to help connect older adults in rural areas during the pandemic [54]; while Henning-Smith et al. (2022b) identified higher levels of social media use among rural dwelling older adults than those living in urban centres in the US [50]. The use of social media to replace face-to-face contact during the COVID-19 pandemic required significant effort on the older adults who chose to do so, including the creation of schedules and strategies to make it more effective [11]. When the digital infrastructure was sufficient, video chats (e.g., FaceTime, Skype) and social media messaging were the choice to stay connected, including the live-streaming of church services [56]. Lund and Ma (2021) found Facebook and Twitter to be the most common form of social media used by older adults in rural areas and small towns, and that older adults were most interested in news relating to health and politics [68]. Beyond the use of social media, other technologies were used to connect people, maintain social networks and stay mentally active. For example, a study conducted in Japan demonstrated that older adults were using video games on their phones as a way to connect to others, keep themselves mentally active, and to combat isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic [53]. Even in cases where the infrastructure to support online digital technologies was lacking, older adults used cell phones and traditional landline phone calls to stay in touch with family and friends [11, 51, 59, 61].

Negative outcomes for rural places

Rural areas commonly experience varying degrees of digital poverty, as compared to urban places, where digital poverty refers to an inability to interact with the online world due to a lack of connectivity or technical ability [69]. Despite reports of general willingness and openness to using new digital technologies, such as social media platforms, older adults often identified these products as inadequate. Within the studies reporting negative experiences using technology, many rural residents were unsatisfied by digital methods to connect to friends and family and longed for face-to-face contact. In fact, Martin et al. (2022) reported older adults living in rural areas responded to the pandemic lockdowns by increasing their use of social media, but they still reported feeling lonely [44]. Many social media users were reporting on experiences in urban places, which caused rural residents to become fearful and confused, despite a relatively low risk of contracting COVID-19 in their immediate rural areas [62]. Additionally, the shift to using digital technologies was also cited as a barrier [52, 70]. Of those who chose not to use digital technology to combat Si/L, the most cited reasons included distrust of social media platforms [47, 70], lack of knowledge in terms of operation and digital skills [52], a lack on connectivity to their personal dwellings [71], and a lack of digital literacy and/or skills [52, 70].

Discussion

In this scoping review, we investigated the effects of social isolation and loneliness of older adults living in rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic. Following an extensive review of the English-language scholarly literature, we analyzed twenty-nine qualitative, quantitative and mixed method articles in the existing literature. We summarized insights into the following four broad themes: (1) Prevalence of social isolation and loneliness, (2) Rural-only research, (3) Urban-Rural comparative research, and (4) Technological and other interventions (Table 3). These thematic categories allowed for a more structured analyses of the studies based on our research questions. The factors central to each of these themes, and related sub-themes, ultimately serve to influence older persons’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the related lockdowns. We also acknowledge that there are interrelationships and a few contradictory findings among the themes, which are indicative of the need for further study in this area. For example, while digital technology and connectivity were found to be limited in some rural areas, other studies reported on the ability of older adults to adopt new technologies, such as social media, to better maintain their social connections. In addition, other factors such as socio-economic status (SES) likely have an effect on the ability of older adults to manage the pandemic and eventual lockdowns. Few articles address these topics and none of the included articles specifically examined aspects such as income, education, and literacy levels. SES would affect both the availability and affordability of technologies that are available in rural areas, creating a dichotomous experience between wealthier and poorer older adults.

The insights offered by these studies provide a wealth of information relevant to the current scoping review. From a human geographic perspective, the rural environment was more suited to the lockdowns because residents could go outside without the fear of being in close contact with others [e.g., 49, 53, 56]. In fact, the inherent experience of geographic isolation in rural places appears to have a positive effect on the resiliency of older adults in terms of their experiences of Si/L [e.g., 47]. Most included studies found the experience of living in isolation to be a protective factor against feeling lonely. The prevalence of loneliness was measured in ten of the thirteen studies relying on quantitative or mixed-methods approaches. Qualitative studies (n = 16) also described feelings of loneliness experienced by older adults living in rural areas during the pandemic. However, the included studies provided conflicting accounts of those in rural places. Studies conducted in the Global South [41, 42, 58,59,60,61] depicted the rural environment as an exacerbating factor for loneliness, those studies conducted in the Global North found the rural environment to be protective or insignificant. Finally, technology was an important tool used by older adults to minimise the effects of Si/L. Fourteen of the included articles specifically explored technology use, which was either high-tech (i.e., social media, video calls) or low-tech (i.e., phone calls, radio programs). The effectiveness of technology to impact Si/L was split with eight studies identifying a positive effect, and six identified a lack of effectiveness or uptake. However, the types of technological interventions are not available in all rural locations, and the included studies highlight these geographical variations and differences. Low-tech devices were the primary technological tools used in LMICs and less affluent areas, detailed by Ekoh et al. (2020, 2021, 2022), Mistry et al. (2022a, 2022b) and Tsiboe et al. (2020) [41, 42, 58,59,60,61]. Less distinction was made in more affluent countries of the Global North, such as Japan, where descriptions included somewhat ambiguous terms such as “social media” [e.g., 62] and “phone-based video games” [e.g., 53].

Research gaps

A key aspect of scoping reviews is to help researchers identify knowledge gaps in the existing literature [35], and several were determined as a result of the current review. While all included studies addressed issues pertaining to Si/L, most studies focused on loneliness, not social isolation. Studies focusing on mental health outcomes, depression and the support systems older adults in rural areas rely on would add to the current discourse. It was also evident that studies focusing on countries in the Global North were over-represented as compared to studies focusing on the Global South. As a consequence, relatively little is known about the geographic differences of Si/L experiences of rural-based older adults. Additionally, rural spaces often lack a specific identity and are identified by what they are not, as opposed to what they are. For example, some included studies included small towns, whereas others explored the experiences in remote areas with very limited and disperse populations. Furthermore, the lack of clarity surrounding the definition of ‘rural’ creates a potential for ecological fallacy – is it an individual isolation experience that is accounting for the association; or, is it the context of the physical environment that accounts for isolation? The resources available in places are often highly varied, specifically in regards to broadband connection for internet and online services. The experiences of these older adults may be very different, despite the fact they might both be identified as rural residents. Researchers seeking to make advances in understanding these factors and experiences will need to identify novel ways of assessing rurality in ways that can be comparable among countries. Additionally, theoretical framing of rural aging may benefit from strength-based resilience and aging models that employ socio-environmental processes to address adversity, such as a pandemic, by integrating individual, community and system-level environmental domains [71].

Studies examining marginalised populations were lacking in this review. Few studies explored lived experiences relating to gender, sexual orientation, and racial or ethnic variations. It is important to highlight the relative lack of studies reporting on non-binary experiences during the lockdowns in general, and more specifically in rural locales. Research that examines such differences, as well as their intersections, can aid in achieving a more nuanced understanding of the factors synthesized, as shown in Table 4. Such insights would be valuable for policy-makers at the municipal, state/province/prefectural and national levels. Building on the abovementioned point, all research directions identified here can benefit from both quantitative and qualitative insights, and we encourage the use of a broader range of mixed methods and the identification of new sources of data. Future studies may benefit from adopting qualitative methods, other than interviews and surveys, such as using personal diaries, mapping exercises, or creating focus groups to expand our knowledge about the factors contributing to the Si/L among older adults in rural environments by drawing on more diversely-generated insights.

Finally, among the gaps in the literature, the lack of studies on LMICs was markedly important in this review. The negative experiences of Si/L resulting from living in rural places during the COVID-19 pandemic was clearer within LMICs. Rural residents are often naturally separated from their families [e.g., 59, 72] as many younger adults (i.e., children of rural-dwelling older adults) tend to migrate to urban centres for greater economic opportunities. The pandemic separated families, and many older rural residents were effectively cut off from their existing familial support structures. Although this was the case in many rural locations [50, 63, 73], the few studies on LMICs in the Global South (n = 6) provided a harrowing account of the experiences facing the most marginalised older adults [58,59,60,61]. Economic hardship was a reality before the lockdowns, but it was exacerbated during the pandemic [41, 42, 58,59,60,61]. The most vulnerable and least supported older adults living in rural areas of LMICs rely for support almost exclusively on their families, particularly on their adult children.

Scoping review limitations

The main limitation to this study is that we omitted sources not written in English. Scoping reviews require parameters, and language is a commonly used one. We, thus, acknowledge that there may be robust scholarly discussions of related experiences in other languages that are not captured in the current review. Another limitation is that there is no universal definition of “rural.” As such, we acknowledge that our review will represent different conceptualisations of what defines rural or remote settings, particularly in different physical geographic locations and we may not have captured articles that described rurality using words other than those found in our keywords. We believe that this potential limitation was mitigated in part due to our post hoc review phase that involved hand-searching of the reference sections of fully reviewed sources, which is a hallmark of the Arksey and O’Malley (2005) scoping review protocol that we followed [35]. Further, while our thematic structure separated rural-only and rural-urban comparative studies, other approaches could be employed that are driven more by content-oriented themes. Finally, this “geropandemic” has been politically and culturally addressed disparately in different countries. This was apparent not only comparing the global south and north, but even occurring within the global north (e.g., Sweden vs. USA vs. Germany), and thus led also to different actions of shutdowns or restriction measures in different years (2020–2022). While we explored experiences relating to “lockdowns” imposed by the relative government authorities, it is important to recognise the differences among the various countries included in the reviewed studies.

Conclusion

Many of the identified motivating factors of the Si/L of older adults living in rural environments during the COVID-19 pandemic seemed complex, interwoven and dichotomous. The juxtaposed nature in which the rural environment was characterised by studies in this review, positive and negative, highlights how little we know about ageing in rural and remote places. Much of the literature available focuses on countries in the Global North and cities. With rural places experiencing accelerated population ageing, as compared to urban centres, due primarily to younger people leaving for opportunities in cities [e.g., 74, 75], researchers need to further explore social isolation and loneliness in rural settings in earnest. Studies exploring the processes and outcomes of Si/L are currently lacking in the existing literature. The association between Si/L with various health issues and challenges underscores the need for more research. Expanding the variation of analytical approaches would also create interesting avenues for future research. This review highlights the lack of studies elucidating the interrelationships between contextual factors at both the macro and micro levels relating to the various processes and outcomes at the nexus of Si/L and ageing and place. Finally, the paucity of literature focusing on rural and/or rural/urban comparisons of Si/L, can be juxtaposed with a more prolific literature on urban dwelling older adults [e.g., 9, 24, 76,77,78]. Overall, this scoping review has systematically identified several important insights about existing knowledge of the experiences of older adults living in rural places during the COVID-19 pandemic, while also identifying the pressing knowledge gaps that can be addressed in future research.

Data Availability

We have provided a detailed description of search strategies within this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- LTC:

-

Long-term care

- LMICs:

-

Lower- and middle-income countries

- SES:

-

Social-Economic Status

- Si/L:

-

Social isolation and loneliness

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- US:

-

United States

References

Iaccarino G, Grassi G, Borghi C, Ferri C, Salvetti M, Volpe M. Age and multimorbidity predict death among COVID-19 patients: results of the SARS-RAS study of the italian society of hypertension. Hypertension. 2020;76(2):366–72.

Mitra AR, Fergusson NA, Lloyd-Smith E, Wormsbecker A, Foster D, Karpov A, Crowe S, Haljan G, Chittock DR, Kanji HD, Sekhon MS. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients with COVID-19 admitted to intensive care units in Vancouver, Canada: a case series. CMAJ. 2020;192(26):E694–701.

Shahid Z, Kalayanamitra R, McClafferty B, Kepko D, Ramgobin D, Patel R, Aggarwal CS, Vunnam R, Sahu N, Bhatt D, Jones K. COVID-19 and older adults: what we know. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(5):926–9.

Thompson DC, Barbu MG, Beiu C, Popa LG, Mihai MM, Berteanu M, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on long-term care facilities worldwide: an overview on international issues. BioMed Res Int. 2020;2020:8870249.

Powell T, Bellin E, Ehrlich AR. Older adults and Covid-19: the most vulnerable, the hardest hit. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50:61–3.

Raina P, Wolfson C, Kirkland S, Griffith LE, Balion C, Cossette B, Dionne I, Hofer S, Hogan D, Van Den Heuvel ER, Liu-Ambrose T. Cohort profile: the canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA). Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(6):1752–3j.

Vannini P, Gagliardi GP, Kuppe M, Dossett ML, Donovan NJ, Gatchel JR, Quiroz YT, Premnath PY, Amariglio R, Sperling RA, Marshall GA. Stress, resilience, and coping strategies in a sample of community-dwelling older adults during COVID-19.J Psychiatr Res.2021;138:176–85.

Rossi R, Jannini TB, Socci V, Pacitti F, Lorenzo GD. Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:635832.

Wister A, Kadowaki L. Social isolation among older adults during the pandemic. Employment and Social Development Canada; 2021.

Melnick ER, Ioannidis JPA. Should governments continue lockdown to slow the spread of Covid-19? BMJ. 2020;369:m1924.

Herron RV, Newall NEG, Lawrence BC, Ramsey D, Waddell CM, Dauphinais J. Conversations in times of isolation: exploring rural-dwelling older adults’ experiences of isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Manitoba, Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3028.

Herron RV, Lawrence BC, Newall NEG, Ramsey D, Waddell-Henowitch CM, Dauphinais J. Rural older adults’ resilience in the context of COVID-19. Soc Sci Med. 2022;306:115153.

Lebrasseur A, Fortin-Bédard N, Lettre J, Raymond E, Bussières EL, Lapierre N, Faieta J, Vincent C, Duchesne L, Ouellet MC, Gagnon E. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults: rapid review. JMIR aging. 2021;4(2), e26474.

Keefe J, Andrew M, Fancey P, Hall M. A profile of social isolation in Canada. Report submitted to the F/P/T Working Group on Social isolation. Province of British Columbia and Mount Saint Vincent University. 2006 May 15.

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:218–27.

Valtorta N, Hanratty B. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: do we need a new research agenda? J R Soc Med. 2012;105:518–22.

Brown DK, Lash S, Wright B, Tomisek A. Strengthening the direct service workforce in rural areas. National Direct Service Workforce Resource Center; 2011.

Rivera-Hernandez M, Ferdows NB, Kumar A. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on older adults in rural and urban areas in Mexico. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2021;76(7):e268–74.

Wilkins R, Lass I, Butterworth P, Vera-Toscano E. The household, income and labour dynamics in Australia survey: Selected findings from waves 1 to 12. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, The University of Melbourne; 2015 Jul 15.

Heenan D. Social capital and older people in farming communities. J Aging Stud. 2010;24(1):40–6.

Sørensen JF. Rural–urban differences in bonding and bridging social capital. Reg Stud. 2016;50(3):391–410.

Tiwari S, Lane M, Alam K. Do social networking sites build and maintain social capital online in rural communities? J rural Stud. 2019;66:1–0.

Ziersch AM, Baum F, Darmawan IG, Kavanagh AM, Bentley RJ. Social capital and health in rural and urban communities in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2009;33(1):7–16.

Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. B M C Public Health. 2020;20:129.

Statistics Canada. From urban areas to population centres (archived). Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/subjects/standard/sgc/notice/sgc-06; 2011.

Konjar M, Kosanović S, Popović SG, Fikfak A. Urban/rural dichotomy and the forms-in-between. Sustain Resil. 2018;149.

Henning-Smith C, Moscovice I, Kozhimannil K. Differences in social isolation and its relationship to health by rurality. J Rural Health. 2019;35(4):540–9.

The Cecil G, Sheps, Center for Health Services Research. 185 rural hospital closures: January 2010 - present. University of North Carolina. 2023. Retrieved Feb 1, 2023 from: http://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/programs-projects/rural-health/rural-hospital-closures/

Wister A, Eireann O, Fyffe I, Cosco TD. Technological interventions to reduce loneliness and social isolation among community-living older adults: a scoping review. Gerontechnology. 2021;20(2):1–6. https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2021.20.2.30-471.11

Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1346–63.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: Opportunities for the health care system. National Academies Press; 2020 Jun. p. 14.

Perlman D, Gerson AC, Spinner B. Loneliness among senior citizens: An empirical report. Essence: Issues in the Study of Ageing, Dying, and Death. 1978.

Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30(4):377.

Wu B. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: a global challenge. Global health research and policy. 2020;5(1):27.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Davis K, Drey N, Gould D. What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1386–400.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–9.

Pickering J, Crooks VA, Snyder J, Morgan J. What is known about the factors motivating short-term international retirement migration? A scoping review. J Popul Ageing. 2019;12:379–95.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Weil J. Research design in aging and social gerontology: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Taylor & Francis; 2017 Feb. p. 24.

Mistry SK, Ali AM, Yadav UN, Huda MN, Ghimire S, Saha M, Sarwar S, Harris MF. Loneliness and its correlates among bangladeshi older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):15020.

Mistry SK, Ali AM, Yadav UN, Khanam F, Huda MN. Changes in loneliness prevalence and its associated factors among bangladeshi older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(11):e0277247.

L’Heureux T, Parmar J, Dobbs B, Charles L, Tian PG, Sacrey LA, Anderson S. Rural family caregiving: A closer look at the impacts of health, care work, financial distress, and social loneliness on anxiety. InHealthcare 2022 Jun 21 (Vol. 10, No. 7, p. 1155). MDPI.

Martin C, Szabo A, Champlin C. A study exploring the impact of COVID-19 on the mental and physical health of older adults in a small rural community: what we learned. Perspectives. 2022;43:6–16.

Pérès K, Ouvrard C, Koleck M, Rascle N, Dartigues JF, Bergua V, et al. Living in rural area: a protective factor for a negative experience of the lockdown and the COVID-19 crisis in the oldest old population? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;36:1950–8.

Egeljić-Mihailović N, Brkić-Jovanović N, Krstić T, Simin D, Milutinović D. Social participation and depressive symptoms among older adults during the Covid-19 pandemic in Serbia: a cross-sectional study. Geriatr Nurs. 2022;44:8–14.

Fuller HR, Huseth-Zosel A. Older adults’ loneliness in early COVID-19 social distancing: implications of rurality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2022;77:e100–5.

Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc Sci Med. 2020;265:113521.

Rutland-Lawes J, Wallinheimo AS, Evans SL. Risk factors for depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in middle-aged and older adults. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e161.

Henning-Smith C, Tuttle M, Tanem J, Jantzi K, Kelly E, Florence LC. Social isolation and safety issues among rural older adults living alone: perspectives of meals on Wheels programs. J Aging Soc Policy. 2022:1–20.

Hanesaka H, Hirano M. Factors associated with loneliness in rural older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: focusing on connection with others. Healthc (Basel). 2022;10:484.

Colibaba A, Skinner MW, Russell E. Rural aging during COVID-19: a case study of older voluntarism. Can J Aging/La Revue canadienne du vieillissement. 2021;40:581–90.

Takashima R, Onishi R, Saeki K, Hirano M. Perception of COVID-19 restrictions on daily life among japanese older adults: a qualitative focus group study. Healthc (Basel). 2020;8:450.

Lenstra N, Oguz F, Winberry J, Wilson LS. Supporting social connectedness of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of small and rural public. Public Libr Q. 2022;41:596–616.

Henning-Smith C, Meltzer G, Kobayashi LC, Finlay JM. Rural/urban differences in mental health and social well-being among older US adults in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Aging Ment Health. 2022:1–7.

Finlay JM, Meltzer G, Cannon M, Kobayashi LC. Aging in place during a pandemic: neighborhood engagement and environments since the COVID-19 pandemic onset. Gerontologist. 2022;62:504–18.

Galkin K. The body becomes closed and squeezed up in a narrow Frame”: loneliness and fears of isolation in the lives of older people in rural areas in Karelia during COVID-19. Anthropol Aging. 2020;41:187–98.

Ekoh PC, Agbawodikeizu PU, Ejimkararonye C, George EO, Ezulike CD, Nnebe I. COVID-19 in rural Nigeria: diminishing social support for older people in Nigeria. Gerontol Geriatr Med. 2020;6:2333721420986301.

Ekoh PC, George EO, Ezulike CD. Digital and physical social exclusion of older people in rural Nigeria in the time of COVID-19. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2021;64:629–42.

Ekoh PC, George EO, Agbawodikeizu PU, Ezulike CD, Okoye UO, Nnebe I. Further distance and silence among kin”: social impact of COVID-19 on older people in rural Southeastern Nigeria. J Intergenerational Relat. 2022;20:347–65.

Tsiboe AK. Describing the experiences of older persons with visual impairments during COVID-19 in rural Ghana. J Adult Prot. 2020.

Ohta R, Yata A. The revitalization of “Osekkai”: how the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the importance of japanese voluntary social work. Qual Soc Work. 2021;20:423–32.

Jensen L, Monnat SM, Green JJ, Hunter LM, Sliwinski MJ. Rural population health and aging: toward a multilevel and multidimensional research agenda for the 2020s. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1328–31.

Van Dijk J. The digital divide. John Wiley and Sons; 2020.

Cheng H, Lyu K, Li J, Shiu H. Bridging the Digital divide for rural older adults by Family intergenerational learning: a Classroom Case in a rural primary school in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):371.

Lee HY, Choi EY, Kim Y, Neese J, Luo Y. Rural and non-rural digital divide persists in older adults: internet access, usage, and perception. Innov Aging. 2020;4(Suppl 1):412.

Scerbe A, Wiley K, Gould B, Carter J, Bourassa C, Morgan D, Jacklin K, Warry W. Anticipated needs and worries about maintaining independence of rural/remote older adults: Opportunities for technology development in the context of the double digital divide. Gerontechnology. 2018;17(3):126–38.

Lund B, Ma J. Exploring information seeking of rural older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aslib J Inf Manag. 2022;74:54–77.

Walker T. Digital poverty transformation: accessing digital services in rural north west communities – Regional policy briefing, Work Foundation. Lancaster University; 2022.

Diehl C, Tavares R, Abreu T, Almeida AMP, Silva TE, Santinha G, et al. Perceptions on extending the use of technology after the COVID-19 pandemic resolves: a qualitative study with older adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14152.

Wister A, Klasa K, Linkov I. A unified model of resilience and aging: applications to COVID-19. Front public health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.865459. 10.

Henning-Smith C. The unique impact of COVID-19 on older adults in rural areas. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32:396–402.

Giwa S, Mullings DV, Karki KK. (2020). Virtual social work care with older black adults: a culturally relevant technology-based intervention to reduce social isolation and loneliness in a time of pandemic. J Gerontol Soc Work, 63(6–7), 679–81.

Skinner M, Hanlon N, Halseth G. Health and social care issues in aging resource communities. Health Rural Can. 2012:462–80.

Skinner MW, Joseph AE, Hanlon N, Halseth G, Ryser L. Growing old in resource communities: exploring the links among voluntarism, aging, and community development. Can Geogr. 2014;58:418–28.

Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:799–812.

National Seniors Council. Scoping review of the literature: social isolation of seniors. 2014. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/national-seniors-council/programs/publications-reports/2014/scoping-social-isolation.html. Accessed 2 Dec 2022.

Kadowaki L, Wister A. Older adults and social isolation and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic: an integrated review of patterns, effects, and interventions. Can J Aging. 2022;8:1–18.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Gerontology reference Librarian at Simon Fraser University, Nina Smart. Nina provided support in the initial phases of the study.

Funding

This study was provided institutional supported for open access publication by Simon Fraser University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.P. wrote the main manuscript text. J.P, A.W. and E.O. reviewed titles. All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pickering, J., Wister, A.V., O’Dea, E. et al. Social isolation and loneliness among older adults living in rural areas during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. BMC Geriatr 23, 511 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04196-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04196-3