Abstract

Background

We aimed to demonstrate the associations between social interactions within social distancing norms during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and cognitive function among South Korean older adults.

Methods

Data from the 2017 and 2020 Survey of Living Conditions and Welfare Needs of Korean Older Persons were used. There were 18,813 participants (7,539 males; 11,274 females). T-test and multiple logistic regression analyses verified whether the mean difference in older adults’ cognitive function before and during the COVID-19 pandemic was statistically significant. We also examined the associations between social interactions and cognitive function. The key results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

All participants were more likely to experience cognitive impairment during the COVID-19 pandemic than before (males: OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.3–1.78; females: OR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.14–1.40). Cognitive impairment increased linearly with the decreased frequency of face-to-face contact with non-cohabiting children. Possible cognitive impairment was greater for females who had not visited senior welfare centers for the past year (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.21–1.69).

Conclusion

Korean older adults’ cognitive function declined during the COVID-19 pandemic and was associated with reduced social interactions because of social distancing measures. Alternative interventions should be promoted for safely restoring social networks, considering the adverse effects of long-term social distancing on older adults’ mental health and cognitive function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The worldwide spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the resulting deaths caused the World Health Organization to declare a global pandemic on March 12, 2020 [1]. Since the first COVID-19 case was reported in South Korea on January 20, 2020, the number of confirmed cases have increased continuously in the past three years [2]. As of February 2023, the cumulative number of confirmed cases in Korea had reached 30 million, and 3 out of 5 people in the entire population were infected.

The Korean government has ardently promoted various public health interventions to prevent transmission, including public campaigns for social distancing, early detection testing, isolation and quarantine measures, and contact tracing. In addition, Korean citizens were instructed to practice personal hygiene, such as wearing masks indoors and outdoors and avoiding private gatherings [2, 3]. These non-pharmaceutical interventions could help control the spread of the virus; however, implementing a long-term social distancing policy faced many challenges; for instance, it incurred higher socio-economic costs [3, 4]. Therefore, the Korean government has declared a new blueprint, “Living with COVID-19” known as “With Corona” to prepare for a gradual return to normal life, and the first phase began on November 1, 2021.

Prolonged social distancing mitigated disease spread effectively and minimized its critical impact on older adults [5]. However, there was a concern that it would adversely affect their mental health; for instance, the lack of social interactions would cause loneliness and isolation [6]. As is well documented, social isolation harms the older adult’s quality of life as well as their physical and mental health [7], and limited social interactions are associated with psychological distress and cognitive deficits among the older people [8,9,10].

However, in Korea, few prior studies have examined the association between social interactions and cognitive function of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, this study aimed to demonstrate the associations between cognitive function and reduced social interactions, in compliance with social distancing measures during the COVID-19 pandemic, among older South Koreans.

Materials and methods

Data

This study used data obtained from the 2017 and 2020 Survey of Living Conditions and Welfare Needs of Korean Older Persons, conducted by the Korean Institute for Health and Social Welfare. This nationwide survey was based on the Elderly Welfare Act, and since 2008, five surveys have been conducted every three years [11, 12]. The question used in each survey are the same, and data collection methods have not changed during the pandemic.

The purpose of this data collection was to provide a basis for establishing welfare policies to improve the older adults’ quality of life, examine changes in their characteristics through time-series data accumulation, and respond to the older population. Since all participants provided informed consent in advance, and the data were publicly accessible, no further ethical approval was required.

Study population

The survey population from the recent two waves (2017 and 2020) included 20,396 individuals. Among the population for this study, we selected the older adults who currently live separately from their children to confirm the impact of decreased face-to-face contact with their non-cohabiting children, in compliance with social distancing measures. After excluding missing data (N = 180), responses from 18,813 participants (7,539 males; 11,274 females) comprised the study sample.

Variables

The dependent variable was cognitive function, assessed using the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination for Dementia Screening (MMSE-DS) [13]. A binary variable was formed based on the criteria that any score over 24 (out of 30) indicates normal cognition, and a score less than 24 is considered cognitive impairment [14, 15]. The main independent variables were the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and the participant’s social interactions. The COVID-19 outbreak variable was classified into two waves: before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2017 and during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The social interactions variable, defined as social behavior patterns that occur when complying with social distancing norms during the pandemic, includes the following three variables: face-to-face contact with their non-cohabiting children (seldom:1 ~ 2 times a year, occasionally: 1 ~ 2 times per quarter, frequently: at least once a week), visiting senior community centers (yes or no), and visiting senior welfare centers (yes or no).

Data regarding socio-demographic factors and health-related variables, potential confounders, included gender, age (65–69, 70–74, 75–79 and 80 or over), region (urban and rural), marital status (unmarried or separated and married), and schooling years (0 ~ 6, 7 ~ 12, and 13 or over). In addition, economic activity was classified based on whether the participants were currently economically active or inactive. Variables regarding health behavior patterns such as drinking, smoking, and physical activity were also considered. Furthermore, experiences of dementia and depression diagnoses from doctors were also corrected.

Statistical analysis

The chi-squared test was conducted to compare the general characteristics of the study population. Subsequently, t-test was performed to verify whether the mean difference in the older adult’s cognitive function between the two waves (before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) was statistically significant. Multiple logistic regression was conducted to examine the associations between social interactions that comply with social distancing norms during the pandemic and cognitive function among older Korean adults. The key results were presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). For all analyses, we used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC, USA), and p-values less than 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Results

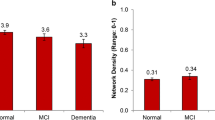

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the study population stratified by gender, in which 29.1% of men (N = 2,193) and 46.7% of women (N = 5,268) were identified as cognitively impaired with an MMSE-DS score of less than 24. After the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of the participants with cognitive impairment was higher for both men and women. Furthermore, based on the t-test results, the mean difference in MMSE-DS scores between the two waves (the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic) was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

Figure 1 illustrates the frequency of change in the participants’ social interactions and the difference between 2017 and 2020. The biggest change was in the frequency of face-to-face contact with their non-cohabiting children. Compared to the period before the COVID-19 outbreak in 2017, the percentage of frequent contact decreased significantly during the pandemic. The percentage of individuals who have frequent contact with their children, at least once a week, has decreased significantly since the pandemic among both those with normal cognitive function (-21.0%p) and those with cognitive impairment(-22.8%p).

As noted in Table 2, the associations between social interactions and cognitive function among older Korean adults were identified. Both men and women were more likely to be cognitively impaired during the COVID-19 pandemic, compared to before the pandemic (Men: OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.36–1.78; Women: OR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.14–1.40). The ORs increased linearly as the frequency of face-to-face contact with the participants’ non-cohabiting children decreased. When a "frequent contact” was set as the reference category, statistical significance was found for “seldom contact” for men (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.10–1.64), and “occasional” and “seldom contact” for women (Occasional contact: OR 1.19, 95% CI 1.07–1.33; Seldom contact: OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.12–1.68). The association between visits to senior community centers and cognitive function was not identified; however, the possibility of cognitive impairment was higher in older women who had not visited senior welfare centers in the past year than it was for those older women who had (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.21–1.69).

We also conducted subgroup analysis stratified by region; Fig. 2 illustrates the results. For example, visits to senior welfare centers in the past year were associated with urban residents’ cognitive impairment. Conversely, a significant change in ORs of cognitive impairment was confirmed for rural residents according to face-to-face contact frequency with their non-cohabiting children.

Discussion

This study presents the following three key findings. First, the mean of the MMSE-DS score, a measure of the prevalence of cognitive impairment, was lower during, compared to before, the COVID-19 pandemic. The MMSE-DS score of the study population before the pandemic was 25.2 ± 5.2 (mean ± SD; median: 26.0) out of 30, and the MMSE-DS score tested during the pandemic was 24.6 ± 6.9 (mean ± SD; median: 25.0) out of 30. Second, changes in social interactions among the older adults before and during the pandemic were noted and are attributed to the impact of strong social distancing measures. The decline in social interactions during the pandemic were relatively greater, especially in the cognitively impaired group. Third, the participants’ social interactions were associated with their cognitive function. This association was investigated particularly among residents in rural areas.

The core results of our study were similar to those in previous studies examining the impacts of social networks, social interactions, social ties, and social isolation on the quality of life of older adults and their mental health, including depression [16,17,18,19], loneliness [20, 21], suicidal ideation [22,23,24], and cognitive function [25]. Many of studies on the health and well-being of older adults have also demonstrated this association [26, 27]; however, few studies have considered the impact of COVID-19 using recent data. Therefore, this study is meaningful in that we used the most recent time-series survey data performed both before and after the COVID-19 outbreak to investigate and compare the impact of social distancing norms during the pandemic on the social interactions among the older Korean adults, and the possibility of cognitive impairment due to reduced social interactions.

Korea has the highest suicide rate of older adults among OECD countries. In addition, Alzheimer’s disease is the seventh leading cause of death, and mental health problems were recognized as a critical phenomenon affecting the mortality of the older population [28]. With this background, we could provide some public health implications by reflecting on current social issues related to the mental health of older Koreans. Amid the crisis caused by the pandemic, the effect of social distancing on COVID-19 incidence and mortality has been proven [29]. However, such interventions can also have adverse effects; for instance, they cause changes in social networks and daily lifestyles. Therefore, social distancing and social support interventions should be implemented simultaneously for socially vulnerable groups such as older individuals. For instance, it would be helpful to provide telehealth services to vulnerable groups suffering from deterioration of physical and mental health [30].

Furthermore, due to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic, most of our social networks are expected to include non-face-to-face communication. Thus, older adults must become accustomed to non-face-to-face interactions, such as video meetings and online classes. In many countries including Korea, job training, leisure activities, and e-learning programs for persons 65 years and older previously held at senior welfare centers, are being implemented in a non-face-to-face system.

This study had certain limitations. First, the data were based on self-reports; hence, the interactions may not have been accurately measured and may be less reliable. It may not be easy for older adults to fully recall their social interactions over the past year, especially those with cognitive impairment. Second, we included only three types of social behavior patterns as the social interactions: face-to-face contact with their non-cohabiting children and visits to senior community centers and welfare center; however, more types of social interactions may be included in future studies. Furthermore, the data excluded the frequency of contact with relatives and friends, which may have decreased during the pandemic. Third, although we attempted to control for numerous covariates that may affect the dependent variable, residual confounding effects from unmeasured variables could not be ruled out.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that cognitive decline in older Korean adults during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with reduced social interactions in compliance with social distancing norms. While social distancing effectively reduced the incidence of and mortality associated with COVID-19, it may have adversely affected older adults’ mental health and cognitive function. Thus, alternative interventions should be promoted to safely restore the social networks during the “With Corona”.

Availability of data and materials

The data is publicly accessible and can be shared through application on the website of Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (https://data.kihasa.re.kr/kihasa/kor/contents/ContentsList.html).

References

Ciotti M, Ciccozzi M, Terrinoni A, Jiang W-C, Wang C-B, Bernardini S. The COVID-19 pandemic. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2020;57(6):365–88.

Choe YJ, Lee J-K. The impact of social distancing on the transmission of influenza virus, South Korea, 2020. Osong Pub Health Res Perspect. 2020;11(3):91–2.

Kim S, Ko Y, Kim Y-J, Jung E. The impact of social distancing and public behavior changes on COVID-19 transmission dynamics in the Republic of Korea. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0238684.

Kim E-A. Social distancing and public health guidelines at workplaces in Korea: responses to coronavirus disease-19. Saf Health Work. 2020;11(3):275–83.

Van Orden KA, Bower E, Lutz J, Silva C, Gallegos AM, Podgorski CA, Santos EJ, Conwell Y. Strategies to promote social connections among older adults during “social distancing” restrictions. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(8):816–27.

Aleman A, Sommer I. The silent danger of social distancing. Psychol Med. 2020;52:1–2.

Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, Turner V, Turnbull S, Valtorta N, Caan W. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health. 2017;152:157–71.

Evans IE, Martyr A, Collins R, Brayne C, Clare L. Social isolation and cognitive function in later life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70(s1):S119–44.

Fu C, Li Z, Mao Z. Association between social activities and cognitive function among the elderly in China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(2):231.

Li HO-Y, Huynh D. Long-term social distancing during COVID-19: A social isolation crisis among seniors? CMAJ. 2020;192(21):E588–E588.

Lee S-Y, Atteraya MS. Depression, poverty, and abuse experience in suicide ideation among older Koreans. Int J Aging Human Dev. 2019;88(1):46–59.

Baek JY, Lee E, Jung H-W, Jang I-Y. Geriatrics fact sheet in Korea 2021. Ann Geriatric Med Res. 2021;25(2):65.

Oh E, Kang Y, Shin J, Yeon B. A validity study of K-MMSE as a screening test for dementia: comparison against a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation. Dement Neurocog Disord. 2010;9(1):8–12.

Crum RM, Anthony JC, Bassett SS, Folstein MF. Population-based norms for the mini-mental state examination by age and educational level. JAMA. 1993;269(18):2386–91.

Nari F, Jeong W, Jang BN, Lee HJ, Park E-C. Association between healthy lifestyle score changes and quality of life and health-related quality of life: a longitudinal analysis of South Korean panel data. BMJ Open. 2021;11(10):e047933.

Mair CA. Social ties and depression: an intersectional examination of Black and White community-dwelling older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2010;29(6):667–96.

Blazer DG. Impact of late-life depression on the social network. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(2):162–6.

Domènech-Abella J, Lara E, Rubio-Valera M, Olaya B, Moneta MV, Rico-Uribe LA, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Mundó J, Haro JM. Loneliness and depression in the elderly: the role of social network. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52(4):381–90.

Rosenquist JN, Fowler JH, Christakis NA. Social network determinants of depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(3):273–81.

Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24(8):1346–63.

Kemperman A, van den Berg P, Weijs-Perrée M, Uijtdewillegen K. Loneliness of older adults: social network and the living environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(3):406.

Heuser C, Howe J. The relation between social isolation and increasing suicide rates in the elderly. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 2019;20(1):2-9.

Dsir TO. Suicide among the elderly in Korea: a meta-analysis. Innov Aging. 2017;1(S1):419.

Mireault M, De Man AF. Suicidal ideation among the elderly: Personal variables, stress and social support. Soc Behav Personal Int J. 1996;24(4):385–92.

Siette J, Georgiou A, Brayne C, Westbrook JI. Social networks and cognitive function in older adults receiving home-and community-based aged care. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;89:104083.

Park S, Kim TH, Eom TR. Impact of social network size and contact frequency on resilience in community-dwelling healthy older adults living alone in the Republic of Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):6061.

Han S, Kim H, Lee H-S. Social Capital and Its Association with Health and Well-Being. Issues and Subpopulations: Health Disparities in Contemporary Korean Society; 2020. p. 23.

Korea S. Cause of death statistics in the Republic Korea, 2019. 2021.

Thu TPB, Ngoc PNH, Hai NM. Effect of the social distancing measures on the spread of COVID-19 in 10 highly infected countries. Sci Total Environ. 2020;742:140430.

Fisk M, Livingstone A, Pit SW. Telehealth in the context of COVID-19: changing perspectives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e19264.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Institute of Health Services Research at Yonsei University for their advice for the further development of this study.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design was performed by Il Yun, while analysis and interpretation of data was performed by Il Yun, Yu Shin Park, and Jaeyong Shin. Il Yun and Eun-Cheol Park drafted and revised the work. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the data used were approved by the Institutional Review Board installed in Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (IRB No. 2020–36). There are no further ethical requirements as participants obtained written informed consent prior to conducting the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, I., Park, Y.S., Park, EC. et al. Associations of social interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic with cognitive function among the South Korean older adults. BMC Geriatr 23, 395 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04112-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-04112-9