Abstract

Background

Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medicine use is common in older people, resulting in harm increased by lack of patient-centred care. Hospital clinical pharmacy services may reduce such harm, particularly prevalent at transitions of care. An implementation program to achieve such services can be a complex long-term process.

Objectives

To describe an implementation program and discuss its application in the development of a patient-centred discharge medicine review service; to assess service impact on older patients and their caregivers.

Method

An implementation program was begun in 2006. To assess program effectiveness, 100 patients were recruited for follow-up after discharge from a private hospital between July 2019 and March 2020. There were no exclusion criteria other than age less than 65 years. Medicine review and education were provided for each patient/caregiver by a clinical pharmacist, including recommendations for future management, written in lay language. Patients were asked to consult their general practitioner to discuss those recommendations important to them. Patients were followed-up after discharge.

Results

Of 368 recommendations made, 351 (95%) were actioned by patients, resulting in 284 (77% of those actioned) being implemented, and 206 regularly taken medicines (19.7 % of all regular medicines) deprescribed.

Conclusion

Implementation of a patient-centred medicine review discharge service resulted in patient-reported reduction in potentially inappropriate medicine use and hospital funding of this service. This study was registered retrospectively on 12th July 2022 with the ISRCTN registry, ISRCTN21156862, https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN21156862.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polypharmacy, defined here as the taking of five or more medicines concurrently, is associated with a high prevalence of potentially inappropriate medicine (PIM – defined in supplementary Table 1) use and occurs frequently in those aged 65 years or over [1,2,3]. PIM use results in poor outcomes including falls, emergency department visits, increased costs, adverse events, and functional decline [4, 5]. Deprescribing - the patient-centred, supervised process of dose reduction or cessation of PIMs [6, 7] - has been identified as part of good prescribing [8] but as limited and reactive rather than proactive, generally occurring because of an adverse event [9]. Deprescribing does not appear to be part of current hospital inpatient practice [10]. Yet the simple count of prescribed medicines at discharge has been shown to outperform complex indicators of therapy quality, such as Beers’ list 2019 [11] and STOPP criteria Version 2 [12] when identifying people at risk and predicting poor outcomes [13].

In Australia, up to 30% of hospital admissions for patients over 75 years of age have been found to be medicine-related, with up to three-quarters potentially preventable, the single most important predictor being the number of medicines taken [2]. The risk of harm and of poor adherence rises with the addition of each new medicine [14, 15], with harm described to be at epidemic proportions [16]. Transitions from hospital to primary care further increase the risk for reasons that include increased medicine sensitivity due to deconditioning and ongoing recovery from acute illness, inaccuracies in medicine reconciliation, insufficient patient education, poor communication with primary care and unexplained medicine changes [17,18,19]. As many as 44% of patients do not follow medicine changes initiated in hospital, continuing to take discontinued medicines, failing to implement dosage changes or to take newly prescribed medicines [20], which may themselves be potentially inappropriate [19].

While the best strategies to combat PIM use in primary care remain unclear [17, 21, 22], effective transitional pharmacist-led strategies have been described [23,24,25,26,27,28]. They have included medicine reconciliation and review in the context of multidisciplinary care, patient counselling, communication with primary care providers and post-discharge follow-up.

Although patient engagement in understanding and managing their medicines is strongly encouraged, it is uncommon [6, 29,30,31,32]. Transitional patient-centred care has been described as poorly understood and a missed opportunity for pharmacists [33], such care recognised as improving patient satisfaction and decision making and reducing adverse events and readmissions [34,35,36,37,38]. A paradigm shift in such care is needed [31, 39].

Australian hospital safety and quality standards state that patients and their caregivers should be actively involved in their care, and that they should receive verbal and written information in ways that are meaningful to them [40]. Patient-directed education or coaching has been shown to be the most influential component of multicomponent interventions for successful transitions [41]. However, there is limited research on the impact of pharmacy health coaching [42], or how well patient-centred care is applied to medicine management in Australian hospitals [37].

Patients have been reported to arrive at hospital taking PIMs, have PIMs commenced and be discharged on PIMs [18]. To address this problem, an implementation program for a discharge medicine review service was begun in 2006 with the development of prescribing appropriateness criteria for older Australians [43]. This criteria set was applied in a scoping study [44], which found a high incidence of PIM use at our hospital. A randomised controlled trial subsequently applied the criteria during medicine review at discharge in intervention patients, sent to patients’ general practitioners (GPs) for actioning. No significant difference in criteria-based recommendations between intervention and control groups were found at follow-up. GPs implemented a relatively low number (42%) of recommendations [45]. This led to a new intervention strategy; the patient and/or caregiver were made the driver of change in reducing their use of PIMs. A patient-centred discharge medicines review service was commenced in 2016.

This study aims to identify the processes, barriers and facilitators that influenced the implementation and intervention effectiveness of this service. For example, limited organisational resources and low leadership engagement have been identified as barriers to implementation of transitional care innovations, whereas adaptability of innovations and high perceived benefit by users identified as facilitators [39]. Implementing research into healthcare practice can be complex and unpredictable, with failure common [46,47,48]. A post-implementation (post hoc) study of these factors was conducted, such studies being commonly used to analyse and explain the implementation process [39, 49]. A prospective audit was conducted to determine the effectiveness of the resulting patient-centred intervention.

Aims of the study

To describe an implementation program in the development of a patient-centred medicine review service; to assess service impact on older patients and their caregivers actioning recommendations after discharge from hospital.

Ethics approvals

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Sydney for each phase of the intervention process, begun in 2006 (project numbers 2011-2015/10043, 2019/209). Approval was also obtained from the Hospitals Medical Executive Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients or their caregivers.

Methods

Implementation process

Many different implementation frameworks have been developed to plan, guide, and evaluate implementation efforts [49,50,51]. Implementation (or process evaluation) dimensions (defined in supplementary Table 1) recommended by the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group [52] were identified by the authors post-intervention that determined the resulting intervention.

To gain a broad understanding of determinants of practice (that is, barriers or facilitators), a checklist resulting from a synthesis of frameworks [51] was chosen to identify determinants responsible for achieving the desired outcome. Combining different frameworks may enable a more comprehensive study [39]. Reporting was guided by the “Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies” checklist [53].

Intervention Setting

The intervention, a prospective post-hospital audit of recommendations made to patients and/or caregivers at discharge, was carried out at a private, not-for-profit 55 bed hospital in Sydney Australia. Patients were admitted for exacerbations of chronic medical conditions such as heart failure, Parkinson’s disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease/asthma, degenerative spinal disease, and inflammatory bowel disease; for rehabilitation after heart, spinal, joint, gastrointestinal, breast or gynaecologic surgery, or trauma from motor vehicle accidents or falls; for palliative care due to metastatic disease; and for management of infections such as cellulitis, pneumonia or urosepsis. Chronic medical conditions and medicines were representative of older Australian community patients [45, 54]. Patients were admitted under the care of one of three geriatricians, rehabilitation specialists or one of two palliative care physicians, supported by two staff doctors. Multidisciplinary care was provided by nursing staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, social workers, and a discharge planner. The clinical pharmacist (BJB) was an experienced medicines review pharmacist.

Eligibility criteria

All patients 65 years or older were eligible. There were no other exclusion criteria. Specifically, patients were not excluded if taking less than five medicines, cognitively impaired, whose second language was English, were being discharged to residential or supportive care, lived distant from the hospital, had a terminal illness, or had vision or hearing impairment.

Intervention

Between July 2019 and March 2020, a convenience sample of 100 patients were recruited for follow-up after discharge. Between one to four patients were discharged daily, the first alternating with the last on a non-alphabetized list being recruited daily. Where cognitive impairment was present, as determined by a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test [55] score of less than 26/30, or where there was language, hearing or vision difficulties, a caregiver was recruited.

Two to three days before discharge, the pharmacist explained to the patient and/or caregiver that sometimes, the benefit of taking certain medicines may be unclear, or the dose may need adjustment. A safer or cheaper medicine or even no medicine at all may be more appropriate. Permission to review their medicines, make recommendations and follow them up was sought, an information sheet provided, and a consent form signed. A medicine list would be provided that detailed the best times to take their medicines, brand names, purpose, cost considerations, relevant side effects and easy-to-understand recommendations to assist with management. Medicines were then reconciled, and reviewed utilizing validated prescribing appropriateness criteria, shown in this setting to detect approximately three quarters of all causes of medicine-related problems (MRPs) [45]. A comprehensive medicine review was conducted according to the protocol of the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia [56], including opportunities for non-pharmacologic care. Patient-directed education was provided during a discharge interview, timing facilitated by allied health staff. Patients/caregivers were encouraged to discuss with their GPs those recommendations important to them for prescription medicines, and to consider for themselves their use of non-prescription medicines. The pharmacist acted as the patient/caregivers’ advocate in proactively addressing PIM use, catering to patient/caregiver health literacy.

The discharge medicine list with recommendations and pharmacist contact details was sent separately to GPs, and where appropriate to aged care facilities, community nurses and pharmacies. Where patients had no GP, support was given finding one. Because it was necessary for all patients to have their medicines reconciled and reviewed and to receive discharge counselling, a control group was not possible. The time taken for each activity was recorded to determine the cost of the service. This included finding medical notes and walking corridors. Patients were invited to fill in a general hospital feedback form at discharge as part of standard practice.

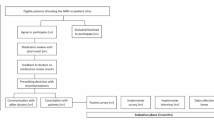

Ten to fourteen days after discharge, each patient or caregiver was contacted, either by phone or in person. Enquiry was made about the actioning of each recommendation, and the results including GP response recorded. Patients’ reports of changes to medicine use were accepted as truthful. Where there had been no visit to a GP or specialist doctor, support and reassurance was provided, and a repeat contact time made. The patient journey consisted of six stages (Figure 1), fitted into episodes of physiotherapy/hydrotherapy attendance, sleep, and mealtimes. Reporting followed the STROBE checklist for observational studies [57].

Data analysis

Data were entered into Microsoft Excel (version 2203), checked for normality, and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Results

Implementation

Processes and determinants identifying actions taken in the implementation of a discharge medicines review service appear in Table 1.

Processes of context, fidelity, implementer engagement, intervention quality and reach (definitions supplementary Table 1) appeared in each phase, as did the following determinants: feasibility; mandate, authority, and accountability; quality assurance and patient safety systems; source of the recommendation. The most commonly occurring determinants were capacity to plan change; implementer engagement; and patient needs, beliefs, knowledge, and motivation.

Intervention

The implemented service was audited between July 2019 and March 2020. Of the 166 patients recruited, 66 were excluded; 11 were transferred to other hospitals due to the occurrence of an acute medical condition such as bleeding or chest pain, or for a procedure unavailable onsite; six left before interview; no recommendations requiring follow-up were made for 33 patients; nine patients were uncontactable after discharge; three had not seen a doctor within four weeks of discharge; three were admitted to another hospital within two weeks of discharge, and one patients family refused follow-up, leaving 100 patients.

All patients/caregivers received a discharge medicine list and review form, and all agreed to participate in a medicines discharge interview and to consider discussing those recommendations important to them with their GP. All patients were followed-up. The pharmacist did not communicate directly with GPs, nor did any GP contact the pharmacist.

Mean participant age was 83.1 years, mean total number of medicines 10.4, with a mean number of 8.9 medical conditions per patient. Of 100 patients, five took less than 5 regular medicines, 48 took five to nine regular medicines, and 47 took 10 regular medicines or more - classed as hyper polypharmacy [3]. Fifty six percent of patients were counselled in the presence of a caregiver. Of 368 recommendations made to 100 patients/caregivers, 351 (95%) were actioned, with 284 (77% of those actioned) reported to be implemented and 206 (21%) regularly taken medicines deprescribed – 141 ceased and 65 medicines reduced in dose (Table 2).

There were 340 causes of a medicine-related problems (MRPs - 3.4 per patient), classified according to a validated system [58]. The top 10 categories represented 92% (312/340) of all causes of MRPs, the most common being: Medicine not effective for the indication treated; medicine was not the most safe/effective; and indication does not warrant medicine treatment (Table 2)

Medicines for acid-related disorders, multivitamins, complementary and alternative medicines, and mineral supplements were the most common medicines ceased. Gabapentinoids, opiates, proton pump inhibitors and statins were the most common medicines reduced in dose. The time taken to reconcile, review and interview patients/caregivers averaged 63.6 minutes/patient.

Recommendations not actioned (17 or 4.6% of the total number) occurred if patients/caregivers decided they were unimportant. Recommendations not implemented occurred because medicines were continued despite evidence provided of poor or absent effectiveness, or GPs considering recommendations unnecessary. Examples included non-discontinuation of glucosamine [59] and prescription of proton pump inhibitors despite apparent lack of indication. Oral feedback about the service from attending doctors and nursing staff, and written feedback from patients presented at patient care committee meetings, was consistently positive with respect to the quality and usefulness of the service.

Examples of medicine management recommendations made to patients appear in supplementary Table 2, according to the cause of their medicine related problem.

Discussion

Continuing positive feedback and the results of this study resulted in our non-government, not-for-profit (private) hospital commencing and continuing to pay for a non-dispensing or cognitive pharmacy service. Facilitators influencing the implementation of transitional care innovations have been identified and include the benefits and usefulness of the innovation to healthcare providers; patient satisfaction resulting in high buy-in from healthcare providers and management; quality of information transfer; clear roles and responsibilities of key team members; support from allied health and administrative staff; and regular communication and feedback about the innovation [39]. These facilitators appear in this study.

Gaining the approval of the Hospital’s executive officers, board of management and medical committee was considered critical in legitimizing the clinical role of the pharmacist. The Hospital supported implementation from inception, providing organizational and policy support. Allied healthcare team support was also essential to facilitate implementation, contributing to the design and evaluation of the service at each stage. This has been found to make interventions more likely to be effective at ward level [60] and represented a participatory action research approach [61]. Such an approach has been used to improve care of delirium in older inpatients [62] and to address inappropriate psychotropic medicine use in residential care [63]. Staff understood that the pharmacist taking time to talk to patients/caregivers about medicines was fundamental to patient care.

Patient-centered care appeared to be of low priority in Australian hospitals [37, 64] and internationally [31, 65, 66], featuring poor delivery of information [28, 67,68,69,70]. Transition interventions involving caregivers also appeared uncommon [25, 31, 41] and often with poor pharmacist involvement [35]. Caregivers need to be recognized as partners in management to reduce communication failures and share information received by patients [32, 71, 72]. Care delivered in this study motivated patients/caregivers to become effective facilitators of medicine management change after discharge. Educating patients/caregivers facilitated crossing the primary-secondary interface, where the pharmacist was made the person for accurately determining and explaining the appropriateness of patients’ medicines and providing it in plainly written form [71]. Such a model of pharmacist care did not appear to be standard practice [73].

In a realist synthesis of pharmacist-conducted medicine reviews in discharged patients [74], factors likely to lead to beneficial outcomes were discussed. Corresponding to these factors, this study engaged healthcare professionals, patients, and caregivers; recruited patients in a trusted environment supportive of the integral role and skill of the pharmacist; established hospital organizational support; provided a pharmacist who understood the critical role of medicine review and integration with staff; and had access to comprehensive information about patients [74].

Handover at transitions of care involved transfer of responsibility to GPs. However, in this study, PIM use was identified and discussed with the patient/caregiver, who were requested to take it up with their GP if it concerned them. This differed from standard practice of pharmacists making recommendations directly to GPs. [24]. GPs then had their attention directed to PIM use by a concerned patient. This proved effective in influencing GPs decision-making behavior (the “nudge” strategy [75]) through overcoming personal cognitive biases, habits, fear of upsetting the patient, therapeutic inertia (failure to alter therapy when indicated [76]) or psychological reactance – a motivational state that affirms a person’s freedom of choice, even if opposite to a recommendation [77].

The presence of MRPs after discharge was not unusual, as hospital doctors may not review long-term medicines unrelated to the current admission, viewing it as the GPs role [78]. After discharge, the GP may assume that medicines have been evaluated and were appropriate to continue. Lack of hospital review represented a lost opportunity, as most older Australians were willing to stop one or more of their regular medicines if their GP said they could [79, 80].

Strengths and limitations

The behavioural nudge featured in this study requires confirmation [81]. Cost of the service appeared dependent upon pharmacist time per patient. Follow-up was short, although persistence of discharge medicine changes following medicine review have been demonstrated [82]. Patients/caregivers reports of medicine changes were accepted as truthful, with no further form of validation. This study was performed in a small hospital by a single pharmacist, limiting generalisability. No clinical outcomes were reported. However, the implementation process delivered a funded service judged effective by management. There were no patient exclusion criteria other than age, adding to real-world impact.

Conclusion

An implementation program resulted in the commencement of a paid patient-centred discharge medicine review service with an implementation rate of recommendations exceeding that of a previous effort. Failure of patient centred care appeared common in hospitals. This, combined with low rates of medicine review in those recently discharged from hospital [32], meant that the epidemic of medicine-related harm may remain undiminished.

Availability of data and materials

Individual participant data is available from Dr Ben Basger at ben.basger@sydney.edu.au upon request. It consists of an Excel spreadsheet containing de-identified patient gender, age, number of medicines taken, and category of medicine related problems identified. All other data generated or analysed during this study is included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- GP:

-

General Practitioner (family doctor)

- MoCA:

-

Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test

- MRP:

-

Medicine Related Problem

- PIM:

-

Potentially Inappropriate Medicine

- STOPP:

-

Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Prescriptions

- STROBE:

-

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

References

Cullinan S, O’Mahony D, Fleming A, et al. A meta-synthesis of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older patients. Drugs Aging. 2014;31:631–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0190-4.

Scott IA, Anderson K, Freeman CR, et al. First do no harm: a real need to deprescribe in older patients. Med J Aust. 2014;201:390–2.

Page AT, Falster MO, Litchfield M, et al. Polypharmacy among older Australians, 2006–2017: a population-based study. Med J Aust. 2019;211:71–5.

Nair NP, Chalmers L, Bereznicki BJ, et al. Adverse drug reaction-related hospitalizations in elderly Australians: A prospective cross-sectional study in two Tasmanian Hospitals. Drug Saf. 2017;40:597–606.

Mekonnen AB, Redley B, de Courten B, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing and its associations with health-related and system-related outcomes in hospitalised older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87:4150–72.

Coe A, Kaylor-Hughes C, Fletcher S, et al. Deprescribing intervention activities mapped to guiding principles for use in general practice: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052547.

Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. Review of deprescribing processes and development of an evidence-based, patient-centred deprescribing process. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:738–47.

Reeve E. Deprescribing tools: a review of the types of tools available to aid deprescribing in clinical practice. J Pharm Pract Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/jppr.1626.

Scott S, Clark A, Farrow C, et al. Deprescribing admission medication at a UK teaching hospital; a report on quantity and nature of activity. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40:991–6.

Bredhold BE, Deodhar KS, Davis CM, et al. Deprescribing opportunities for elderly inpatients in an academic, safety-net health system. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2021;17:541–4.

American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:674–94.

O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–8.

De Vincentis A, Gallo P, Finamore P, et al. Potentially inappropriate medications, drug-drug interactions and anticholinergic burden in elderly hospitalized patients: Does an association exist with post-discharge health outcomes? Drugs Aging. 2020;37:585–93.

Rasmussen MK, Ravn-Nielsen LV, Duckert M-L, et al. Cost-consequence analysis evaluating multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention targeting patient transitions of care from hospital to primary care. JACCP 2018:2 (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/jac5.1042.

Threapleton CJD, Kimpton JE, Carey IM, et al. Development of a structured clinical pharmacology review for specialist support for management of complex polypharmacy in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:1326–35.

Mangin D, Bahat G, Golomb BA, et al. International group for reducing inappropriate medication use and polypharmacy (IGRIMUP): Position statement and 10 recommendations for action. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:575–87.

Parekh N, Ali K, Davies JG, et al. Medication-related harm in older adults following hospital discharge: development and validation of a prediction tool. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;29:142–53.

Weir DL, Lee TC, McDonald DG, et al. Both new and chronic potentially inappropriate medications continued at hospital discharge are associated with increased risk of adverse events. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:1184–92.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2020) Medication without harm - WHO global patient safety challenge. Australia's Response. Sydney: ACSQHC.: 1-52. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/medication-without-harm-who-global-patient-safety-challenge-australias-response Accessed 12 November 2022.

Freeman CR, Scott IA, Hemming K, et al. Reducing medical admissions and presentations into hospital through optimising medicines (REMAIN HOME): a stepped wedge, cluster randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2021;214:212–7.

Garfinkel D, Bilek A. Inappropriate medication use and polypharmacy in older people. BMJ 2020;369:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2023

Steinman MA. Reducing hospital admissions for adverse drug events through coordinated pharmacist care: learning from Hawai’i without a field trip. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:91–3.

Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien JE. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/2/e010003.full.pdf

Van-der-Linden L, Hias J, Walgraeve K, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in older inpatients: An evidence-based review. Drugs Aging. 2020;37:161–74.

Ravn-Nielsen LV, Duckert M-L, Lund ML, et al. Effect of an in-hospital multifaceted clinical pharmacist intervention on the risk of readmission. A randomised controlled trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:375–82.

Miller D, Ramsey M, L’Hommedieu TR, et al. Pharmacist-led transitions-of-care program reduces 30-day readmission rates for Medicare patients in a large health system. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2020;77:972–8.

Snyder ME, Krekeler C, Jaynes HA, et al. Evaluating the effects of a multidisciplinary transition care management program on hospital readmissions. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2020;77:931–7.

Capiau A, Foubert K, Van der Linden L, et al. Medication counselling in older patients prior to hospital discharge: A systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2020;37:635–55.

Manias E, Hughes C. Challenges in managing medications for older people at transition points of care. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2015;11:442–7.

Mohammed MA, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Medication-related burden and patients' lived experience with medicine: a systematic review and metasynthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open 2016: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/2/e010035.full.pdf

Liebzeit D, Rutkowski R, Arbaje AI, et al. A scoping review of interventions for older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:2950–62.

Page AT, Cross AJ, Elliott RA, et al. Integrate healthcare to provide multidisciplinary consumer-centred medication management: report from a working group formed from the National Stakeholders' meeting for the quality use of medicines to optimise ageing in older Australians. J Pharm Pract Res 2018: https://doi.org/10.1002/jppr.1434

Ozavci G, Bucknall T, Woodward-Kron R, et al. A systematic review of older patients’ experiences and perceptions of communication about managing medication across transitions of care. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2021;17:273–91.

Selby JV, Beal AC, Frank L. The patient-centred outcomes research institute (PCORI) national priorities for research and initial research agenda. JAMA. 2012;307:1583–4.

Rodakowski J, Rocco PB, Ortiz M, et al. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: A metaanalysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:1748–55.

Eassey D, Smith L, Krass I, et al. Consumer perspectives in medication-related problems following discharge from hospital in Australia: a quantitative study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28:391–7.

Bucknall T, Digby R, Fossum M, et al. Exploring patient preferences for involvement in medication management in hospitals. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:2189–99.

Rayan-Gharra N, Balicer RD, Tadmor B, et al. Association between cultural factors and readmissions: the mediating effect of hospital discharge practices and care-transition preparedness. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:866–74.

Fakha A, Groenvynck L, de Boer BvA, T., et al. A myriad of factors influencing the implementation of transitional care innovations: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2021: 16; 21 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33637097/Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. 2nd ed. Sydney: ACSQHC.: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-second-edition.pdf Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Tomlinson J, Cheong V-L, Fylan B, et al. Successful care transitions for older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of interventions that support medication continuity. Age Ageing. 2020;49:558–69.

Singh HK, Kennedy GA, Stupans I. A systematic review of pharmacy health coaching and an evaluation of patient outcomes. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2019;15:244–51.

Basger BJ, Chen TF, Moles RJ. Inappropriate medication use and prescribing indicators in elderly Australians. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:777–93.

Basger BJ, Chen TF, Moles RJ. Application of a prescribing indicators tool to assist in identifying drug-related problems in a cohort of older Australians. Int J Pharm Pract. 2012;20:172–82.

Basger BJ, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Impact of an enhanced pharmacy discharge service on prescribing appropriateness criteria - a randomised controlled trial. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:1194–205.

Garcia-Cardenas V, Perez-Escamilla B, Fernandez-Llimos F, et al. The complexity of implementation factors in professional pharmacy. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2018;14:498–500.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38:65–76.

Uitvlugt EB, En-nasery-de-Heer S, Van den Bemt BJF, et al. The effect of a transitional pharmaceutical care program on the occurrence of ADEs after discharge from hospital in patients with polypharmacy. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2022;18:2651–8.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, et al. A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implement Sci 2016;11:72.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Hunter SC, Kim B, Mudge A, et al. Experiences of using the i-PARIHS framework: a co-designed case study of four multi-site implementation projects. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):72.

Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: A systematic review and synthesis frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8:35–46.

Cargo M, Harris J, Pantoja T, et al. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group guidance paper - paper 4: methods for assessing evidence on intervention implementation. J Clin Epidemiol. 2018;97:59–69.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, Rycroft-Malone J, Meissner P, Murray E, Patel A, Sheikh A, Taylor SJC (2017) Standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement. BMJ 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6795

NPS MedicineWise (2018) General Practice Insights Report July 2016-June 2017: A working paper. Sydney. National Prescribing Service 2018.1-84. https://www.nps.org.au/assets/63df68106933b7b1-100a108a779c-GPIR-2016_17_FinalVersion13-Dec.pdf Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:695–9.

Sansom L, ed. Medicines Review; Australian Pharmaceutical Formulary and Handbook 24th edition Canberra. Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2018:173–175. https://apf.psa.org.au.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–7.

Basger BJ, Moles RJ, Chen TF. Development of an aggregated system for classifying causes of Drug Related Problems (DRPs). Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49:405–18.

Wandel S, Juni P, Tendal B, et al.Effects of glucosamine, chondroitin, or placebo in patients with ost eoarthritis of hip or knee: network meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;341: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4675

Casey M, O’Leary D, Coghlan D. Unpacking action research and implementation science: Implications for nursing. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1051–8.

Cordeiro L, Soares CB. Action research in the healthcare field: a scoping review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2018;16:1003–47.

Day J, Higgins I, Koch T. The process of practice redesign in delirium care for hospitalised older patients: A participatory action research study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:13–22.

Kormelinck CMG, van Teunenbroek CF, Kollen BJ, et al. Reducing inappropriate psychotropic drug use in nursing home residents with dementia: protocol for participatory action research in a stepped wedge cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry 2019;19(1):298. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2291-4 Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Tong EY, Edwards G, Hua PU, et al. Systematic review of clinical outcomes in clinical pharmacist roles in hospitalised general medicine patients. J Pharm Pract Res. 2020;50:297–307.

Bonetti AF, Reis WC, Lombardi NF, et al. Pharmacist-led discharge medication counselling: A scoping review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2018;24:570–9.

Fernandes BD, Almeida PHRF, Foppa AA, et al. Pharmacist-led medication reconciliation at patient discharge: A scoping review. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2020;16:605–13.

Mahfouz C, Bonney A, Mullan J, et al. An Australian discharge summary quality assessment tool: A pilot study. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46:57–63.

Aubert CE, Kerr EA, Maratt JK, et al. Outcome measures for interventions to reduce inappropriate chronic drugs: A narrative review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68:2390–8.

Bekker CL, Naghani SM, Natsch S, et al. Information needs and patient perceptions of the quality of medication information available in hospitals: a mixed method study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42:1396–404.

Weir DL, Motulsky A, Abrahamowicz M, et al. Failure to follow medication changes made at hospital discharge is associated with adverse events in 30 days. Health Serv Res. 2020;55:512–23.

Manias E, Gerdtz M, Williams A, et al. Communicating about the management of medications as patients move across transition points of care: an observation and interview study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22:635–43.

Garfield S, Furniss D, Husson F, et al. How can patient-held lists of medication enhance patient safety? A mixed-methods study with a focus on user experience. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29:764–73.

Shane RR. Why is the patient here? What do they need? Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2020;77:901–2.

Luetsch K, Rowett D, Twigg MJ. A realist synthesis of pharmacist-conducted medication reviews in primary care after leaving hospital: what works for whom and why? BMJ Qual Saf. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011418.

Lamprell K, Tran Y, Arnolda G, et al. Nudging clinicians: A systematic scoping review of the literature. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021;27:175–92.

Byrnes PD. Why haven’t I changed that? Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:24–8.

de Almeida NA, Chen TF. When pharmacotherapeutic recommendations may lead to the reverse effect on physician decision-making. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:3–8.

Alldred DP. Deprescribing: a brave new word? Int J Pharm Pract. 2014;22:2–3.

Thillainadesan J, Gnjidic D, Green S, et al. Impact of deprescribing interventions in older hospitalised patients on prescribing and clinical outcomes: A systematic review of randomised trials. Drugs Aging. 2018;35:303–19.

Qi K, Reeve E, Hilmer SN, et al. Older peoples attitudes regarding polypharmacy, statin use and willingness to have statins deprescribed in Australia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2015;37:949–57.

Fox CR, Doctor JN, Goldstein NJ, et al. Details matter: predicting when nudging clinicians will succeed or fail. BMJ. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3256.

Debacq C, Bourgueil J, Aidoud A, et al. Persistance of effect of medication review on potentially inappropriate prescriptions in older patients following hospital discharge. Drugs Aging. 2021;38:243–52.

Pintor-Marmol A, Baena MI, Fajardo PC, et al. Terms used in patient safety related to medication: a literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:799–809.

Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Seger AC, et al. Adverse drug events and medication errors: detection and classification methods. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:306–14.

Rantsi M, Hyttinen V, Jyrkka J, et al. Process evaluation of implementation strategies to reduce potentially inappropriate medication prescribing in older population: A scoping review. Res Soc Admin Pharm. 2022;18:2367–91.

de Consenso Comite. Third consensus of Grenada on drug related problems and negative outcomes associated with medicines. Ars Pharm. 2007;48:5–17.

Australian Government Department of Health (2022) Medication management reviews. https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/medication_management_reviews.htm Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Brickley B, Williams LT, Morgan M, et al. Patient-centred care delivered by general practitioners: a qualitative investigation of the experiences and perceptions of patients and providers. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2020-011236.

Opondo D, Eslami S, Visscher S, et al. Inappropriateness of medication prescriptions to elderly patients in the primary care setting: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043617&type=printable Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

O’Mahony D, Gallagher PF. Inappropriate prescribing in the older population: need for new criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37:138–41.

Bala SS, Chen TF, Nishtala PS. Reducing potentially inappropriate medications in older adults: A way forward. Can J Aging. 2019;38:419–33.

O’Connor MN, Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. Inappropriate prescribing. Criteria, detection and prevention. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:437–52.

Basger BJ, Chen TF, Moles RJ. Validation of prescribing appropriateness criteria for older Australians using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. BMJ Open 2012. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/5/e001431.long Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

World Health Organisation (2019) International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8577172/ Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

World Health Organisation. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system index. ATC/DDD Index 2020. World Health Organisation www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/ Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Medibank Private Health Insurance (www.medibank.com.au) provided a grant of AU$30,000 in 2006 to commence this research. The Board of Management of Wolper Jewish Hospital provided a grant of AU$15,000 in 2019 to follow up patients after discharge. The Hospital was not involved in any other aspect of this research, such as study design, analysis, interpretation, writing or submission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BJB contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing the original draft, review editing, submission, and project administration. RJM contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, validation, review and editing the manuscript, project administration and supervision. TFC contributed to conceptualisation, methodology, validation, review and editing of the manuscript, project administration and supervision. All authors' read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of The University of Sydney for each phase of the intervention process, begun in 2006 (project numbers 2011-2015/10043) and provided for this current study (2019/209). Approval was also obtained from the Hospitals Medical Executive Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual patients or their caregivers following verbal and written discussion and information provided by the clinical pharmacist (BJB). This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

TFC and RJM declare no competing interests. BJB is employed as a clinical pharmacist by Wolper Jewish Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Basger, B.J., Moles, R.J. & Chen, T.F. Uptake of pharmacist recommendations by patients after discharge: Implementation study of a patient-centered medicines review service. BMC Geriatr 23, 183 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03921-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-023-03921-2