Abstract

Background

Aging is an inevitable process of life development. These physical changes may cause a decline in the functional adaptability and health of older adults. This study aims to determine if an association exists between health-related physical fitness measurements and self-reported health status in older Taiwanese adults.

Methods

A total of 22,389 Taiwanese adults aged 65 years or older were recruited as study participants. Demographic characteristics, life habits, anthropometric assessments, health-related physical fitness measurements, and self-reported health status from this dataset were analyzed using the chi-square test, one-way analysis of variance, and logistic regression analysis.

Results

The results showed that there was significant association between back scratch and self-reported health status (excellent/good) (odds ratio [OR], 1.003; 95% CI 1.000–1.006) after adjusting potential confounders (gender, height, weight, body mass index, education, monthly income, marital status, smoking status, and chewing betel nuts). However, adjusted OR for unhealthy status (poor/very poor) significantly decreased for chair sit-and-reach test (OR 0.994, 95% CI 0.988–0.999).

Conclusions

The present study reveals significant associations between health-related physical fitness measurements and self-reported health status in older Taiwanese adults. In particular, the waist-to-hip ratio could be involved in the cognitive process of one’s subjective health status, since individuals’ perception of their physical appearance affects their self-reported health. Future researches are suggested to investigate the causality between health-related physical fitness and subjective health status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aging is an inevitable process of life development. One characteristic of aging is the degradation of the human musculoskeletal system, which leads to a decrease in muscle mass and lower muscle function [1, 2]. These physical changes may cause a decline in the functional adaptability and health of older adults.

Recently, researchers have increased their focus on health and aging. According to the World Health Organization [3], “health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” Physical fitness is a multi-factor indicator. The basic measures of physical fitness include height, weight, body mass index (BMI), body function, medical history, body composition, and age. Numerous advanced measures are also used to assess physical fitness, including cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular endurance, muscular strength, and body flexibility [4,5,6].

Obviously, in the advanced measures used to assess physical fitness, musculoskeletal-related measurements account for the majority. Musculoskeletal health consists of three elements: muscular strength, muscular endurance, and flexibility [4]. If these elements cannot be maintained, the fitness of the musculoskeletal system may be damaged. Musculoskeletal interaction is the essential for body movement, so poor musculoskeletal health will directly affect the physical condition of the individual. Kell et al. [7] pointed out that the execution of daily tasks may become a challenge due to age. They also illustrated that the combination of resistance training and stretching to improve musculoskeletal health is related to enhanced health. In addition, numerous studies have established the relationships of general physical fitness with health status and quality of life [4, 8,9,10].

Sato et al. used multiple discriminant analysis to quantify the relationship between the health status and physical fitness of middle-aged and older adults (ages 30 to 60 years) [8]. Their results revealed a relationship between health status and physical fitness. Daily physical activity may positively affect the health of middle-aged and older people. However, few studies have mentioned the relationship between physical fitness measurement and self-reported health status. Instead, most researchers have used physician assessments to determine the health status of participants.

Sato et al. have explored the relationship between the health status and physical fitness of middle-aged and older men [9] and women [10] in Japan. The studies identified components of physical fitness that helped to improve and maintain health in different age groups and quantified the relationship of health status with physical fitness in middle-aged and older individuals. For example, they suggested that for men aged 50 to 59, maintaining a normal BMI and improving cardiorespiratory endurance and balance are effective. For men aged 60 to 69, maintaining and improving flexibility and paying attention to body fat percentage are most important [9]. In addition, for women between the ages of 50 and 69, maintaining the percentage of body fat within an appropriate range is most important [10].

When researchers want to compare the health status between groups, self-reported health indicators are commonly used (also known as self-rated health). Self-reported health is a comprehensive measure of individual’s overall health and can be regarded as the output of an individual’s physical function and subjective self-health awareness [11].

We found no relevant research on the relationship between health status and physical fitness in Taiwan. Determining factors related to self-reported health is very important for overall population health, especially due to the aging trend of the overall population [12]. Determining these factors can also help the government formulate relevant incentive policies promote the health of the people [11]. Therefore, this study aims to determine if an association exists between health-related physical fitness measurements and self-reported health status in older Taiwanese adults.

Methods

Study design and participants

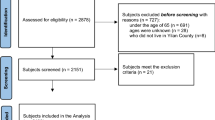

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine the associations between physical fitness components and self-reported health status in older Taiwanese adults. We reviewed data derived from the National Physical Fitness Survey Databases in Taiwan (NPFSD 2014–15) from Taiwan’s Sports Administration, a branch of the Ministry of Education. All participants were recruited using convenience sampling from 35 examination stations in 20 cities or counties in Taiwan; the detailed procedure has been described elsewhere [13,14,15]. Participants completed a questionnaire on their demographic characteristics and life habits, and we measured resting heart rate and blood pressure for safe preliminary screening before conducting physical fitness measurements. Finally, for this study, we assayed the questionnaire and physical fitness measurement data of 22,389 Taiwanese adults aged 65 years and older. The data was collected between October 2014 and March 2015. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Fu Jen Catholic University (FJU-IRB-C108088), and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Data collection

Face-to-face interviews and physical examinations were completed by trained research assistants and nurses. The questionnaire data included demographic characteristics (i.e., age, gender, education, monthly income, and marital status), life habits (i.e., smoking, betel-nut chewing, and dieting), and self-reported health status. Anthropometric measurements including body weight, height, waist circumference (WC), and hip circumference (HC) were taken after the participants had removed their shoes and heavy clothes. Body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a weighing scale. Body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a metal measuring tape attached to a wall with an acute-angled head piece; the participants stood against this vertical wall and wore no shoes. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. WC was measured (to the nearest 0.1 cm) by using a soft measuring tape at the level of the natural waist, which was identified as the level at the hollow molding of the trunk when the trunk was bent laterally. HC was measured (to the nearest 0.1 cm) at the level of the greater trochanter. The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) was also calculated. The cut-off BMI values were those suggested by Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare: underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24 kg/m2), overweight (24 ≤ BMI < 27 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2) [16].

Self-reported health status

Self-reported health status and obtained from the following questionnaire item: “In general, would you say your health is excellent, good, fair, poor, or very poor?” In this analysis, we have combined the responses into a ternary outcome, where self-reported health status could be health status (a response of “excellent” or “good”), fair (a response of “fair”), or unhealthy status (a response of “poor” or “very poor”), in order to concentrate the categories for further comparisons. This approach has been presented in the previous studies [13,14,15].

Physical fitness measurements

To determine the functional capacity of older adults, we assessed five main components of physical fitness based on nine indicators: aerobic endurance (2-min step), muscle strength and endurance (30-s arm curl and 30-s chair stand), flexibility (back scratch and chair sit-and-reach), balance (one-leg stance with eyes open and 8-ft up-and-go), and body composition (BMI and WHR). Each physical fitness indicator had accompanying performance standards for male and female participants aged 65 years and older based on an annual national survey of more than 20,000 older Taiwanese adults. Measurements and above-mentioned data were recorded by examiners who had attended an official training seminar and passed a certification test on standardized procedures. The details of the 2-min step, 30-s arm curl, 30-s chair stand, back scratch, chair sit-and-reach, and 8-ft up-and-go were strictly performed according to the Senior Fitness Test manual [17], and the one-leg stance with eyes open was as described in other articles [18].

The content and the process of the physical fitness measurements were explained to the participants, and they had 10 min to warm up so that their optimum performance could be achieved. Measurements were scheduled before the exercises. All participates were assessed in the following order with sufficient rest (3 to 5 min) between measures: body weight, height, WC, HC, one-leg stance with eye open, 30-s chair stand, 30-s arm curl, 2-min step, chair sit-and-reach, back scratch, and 8-ft up-and-go. For each indicator, the participants were classified into four quartiles according to their physical fitness performance levels.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software package (Version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Differences in demographic data and physical fitness measurements between categories of self-reported health status were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-square tests. When a significant F value was found (p < 0.05), Tukey’s post hoc test was performed to determine the differences between the pairs of means. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between quartiles of each physical fitness measurements and self-reported health status (excellent/good vs. fair and poor/very poor vs. fair) while adjusting for potential confounders. All data are expressed as means ± standard deviation or frequency (percentage). The significance level adopted to reject the null hypothesis was p < 0.05.

Results

This study obtained data from 22,389 participants aged 65 years and older. The relationship between demographic characteristics and anthropometric indices of self-reported health status are shown in Table 1. Significant associations were identified between self-reported health status and all the demographic characteristics except age. Participants whose self-reported health status was excellent or good were the tallest (156.77 ± 7.92 cm) and heaviest (60.88 ± 9.75 kg).

Table 2 compares the physical fitness measurements between self-reported health status categories. Significant associations were observed between self-reported health status and physical fitness. Both men and women whose self-reported health status was excellent or good had the highest levels of physical fitness (2-min step test, 30-s arm curl, 30-s chair stand, back scratch, chair sit-and-reach test, 8-ft up-and-go, and one-leg stance with eyes closed), but no significant association was identified between self-reported health status and BMI in men (p = 0.112).

Tables 3 and 4 represent the relationship between physical fitness and self-reported health status (excellent/good) after adjusting for potential confounders (gender, height, weight, BMI, education, monthly income, marital status, smoking status, and chewing betel nuts). Before adjusting, no significant associations were identified between five physical fitness indicators (back scratch: OR = 1.002, 95% CI 0.999–1.004; chair sit-and-reach test: OR = 1.002, 95% CI 0.999–1.005; one-leg stance with eye open: OR = 1.002, 95% CI 0.998–1.005; BMI: OR = 1.004, 95% CI 0.995–1.014; WHR: OR = 1.047, 95% CI 0.670–1.637) and self-reported health status (excellent/good). However, after adjustment, a significant association between the back scratch indicator and self-reported health status (excellent/good) was revealed (OR = 1.003; 95% CI 1.000–1.006). No significant relationships were observed between six physical fitness indicators (2-min step test: OR = 0.999, 95% CI 0.997–1.001; 30-s arm curl: OR = 0.992, 95% CI 0.982–1.003; back scratch: OR = 0.997, 95% CI 0.993–1.002; chair sit-and-reach test: OR = 0.995, 95% CI 0.989–1.001; BMI: OR = 1.012, 95% CI 0.995–1.028; WHR: OR = 1.010, 95% CI 0.449–2.273) and low self-reported health status (poor/very poor). However, once the results were adjusted for potential confounders, the ORs for self-reported health status (poor/very poor) decreased, and the correlation became significant for the chair sit-and-reach test (OR = 0.994, 95% CI 0.988–0.999).

Discussion

In this study, we examine the relationship between self-reported health status and physical fitness measurement results. The results indicate that regardless of gender, participants who perceived their health status as good exhibited significantly higher physical fitness measurement results than those in the other two groups, who reported their health status as either fair or poor. Therefore, the present study indicates that people with good self-reported health status also perform higher in physical fitness.

In addition, body shape is a factor for woman that affects self-reported health status. Nonetheless, the relationship between BMI and self-reported health status was not significant in men (p = 0.112). However, for women in this sample, the relationship between BMI and self-reported health status was statistically significant (p < 0.001) which means the heavier weight (normal BMI) have the better self-reported health. According to the results, the BMI are significant different among different self-reported health group in women but not men. We conclude that this may be related to the fact that women are more concerned about body shape [19]. Generally speaking, women still feel obese when they are of normal weight. Therefore, this may cause women to reach statistical significance in the relationship between BMI and self-reported health status. The limitation of this study is that the unbalanced male to female ratio of participants of this data collection. This gender difference may be caused by the convenience sampling which the gender ratio subjects was 1:2 (male: female) of this convenience sample. Therefore, in future research design, we suggest increasing the sample size and controlling the gender ratio to examine gender differences in the association between BMI and self-reported health status. In addition, there were significant bivariate associations between WHR and general health among men and women (that did not hold in adjusted analyses). We suggest that WHR may be a superior predictor than BMI in the future research. Although BMI is a very intuitive indicator for the definition of obesity, not all individuals at risk for obesity-related diseases are identified [20]. Additionally, individuals with large muscle proportions will generally have a relatively high BMI. It is also unlikely to define these individuals as obese.

The advantage of this study is that it uses data collected by the NPFSD for Taiwan’s Sports Administration. This data comes from different counties and cities across Taiwan and is therefore representative. Thus, it eliminates the researcher’s sampling selection bias. Furthermore, according to the literature review, although there are numerous studies have established the relationships of general physical fitness with health status and quality of life [4], few studies have examined the correlation between physical fitness performance and health among older adults. Sato et al. examined the relationship between anatomical structure and the quality of life related to body function and health [21]. They found that by verifying physical fitness measurement, health status can be estimated with relative accuracy. Another study confirmed that different musculoskeletal components have a strong influence on health status and quality of life which suggested that providing interventions for the older adults with high body weight, low lower limb strength, poor lumbosacral flexion ability and poor balance ability can improve their health and quality of life [4].. In this analysis, we examine the association between physical fitness and self-reported health status. The cross-sectional study design was also a limitation of this study. We cannot confirm the causality between these two variables. Therefore, we can continue to examine whether living habits may be mediating or moderating variables. In addition, different physical fitness measures could also be compared in future studies.

Evidence clearly supports the notion that exercise contributes to healthy aging. Angevaren et al. [22] concluded that aerobic physical exercise that improves cardiorespiratory health is beneficial to adults’ cognitive function. However, in their research, most of the comparisons results were not statically significant. In addition, with regard to improving the health of older adults, healthcare providers must take into account appropriate physical exercises to maintain and improve the level of physical health [23]. Research has also shown that physical activity improves the health of older adults [24]. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the factors affecting health, we suggest that future studies include surveys of older adults’ exercise routines. Finally, due to a government provided questionnaire was conducted, the measurement of subjective health status may be insufficient which is also a limitation of this study. The self-reported health scale, such as SF-12, SF-36, should be applied for the future studies [4]. Also, quality of life survey is recommended to take part in the analysis in order to distinguish the dimensions of health status. In future research, we suggest that a more comprehensive self-reported health status survey be provided to obtain more information.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the effect sizes are finite in relevant comparisons, the present study reveals significant associations between health-related physical fitness measurements and self-reported health status in older Taiwanese adults. In particular, the WHR could be involved in the cognitive process of one’s subjective health status. WHR can be considered an indicator of physical appearance [19]. Therefore, individuals’ perceptions of their physical appearance affect their scores on self-reported health. Future researches are suggested to investigate the causality between health-related physical fitness and subjective health status.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from [the Sports Cloud: Information and Application Research Center of Sports for All, Sport Administration, Ministry of Education in Taiwan] but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of [the Sports Cloud: Information and Application Research Center of Sports for All, Sport Administration, Ministry of Education in Taiwan].

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HC:

-

Hip circumference

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- NTD:

-

New Taiwan Dollar

- SAS:

-

Statistical Analysis System

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- WHR:

-

Waist-to-hip ratio

References

Pedrero-chamizo R, Gómez-cabello A, Mélendez A, Vila-maldonado S, Espino L, Gusi N, et al. Higher levels of physical fitness are associated with a reduced risk of suffering sarcopenic obesity and better perceived health among the elderly. the EXERNET multi-center study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2015;19(2):211–7.

Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Fielding RA, Fiatarone MA, Evans WJ, Roubenoff R. Aging of skeletal muscle: A 12-yr longitudinal study. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88(4):1321–6.

World Health Organization. (n.d.). WHO remains firmly committed to the principles set out in the preamble to the Constitution. https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/constitution.

Cuesta-Vargas A, Galán-Mercant A. Contribution of physical fitness component to health status in elderly males and females over 60 years-short report. SA J Physiother. 2012;68(1):4–8.

Wilder RP, Greene JA, Winters KL, Long WB 3rd, Gubler K, Edlich RF. Physical fitness assessment: an update. J Long-Term Eff Med Implants. 2006;16(2):193–204.

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). General principles of exercise prescription. In: A.C.S.M.´S. Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

Kell R, Bell G, Quinney A. Musculoskeletal fitness, health outcomes and quality of life. Sports Med. 2001;31(12):863–73.

Sato T, Demura S, Murase T, Kobayashi Y. Quantification of relationship between health status and physical fitness in middle-aged and elderly males and females. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2005;45(4):561–9.

Sato T, Demura S, Murase T, Kobayashi Y. Contribution of physical fitness component to health status in middle-aged and elderly males. J Physiol Anthropol. 2006;25(5):311–9.

Sato T, Demura S, Murase T, Kobayashi Y. Contribution of physical fitness component to health status in middle-aged and elderly females. J Physiol Anthropol. 2007;26(6):569–77.

Manderbacka K. Examining what self-rated health question is understood to mean by respondents. Scand J Soc Med. 1998;26(2):145–53.

Lundberg O, Manderbacka K. Assessing reliability of a measure of self-rated health. Scand J Soc Med. 1996;24(3):218–24.

Chen HH, Chen HL, Lin YT, Lin CW, Ho CC, Lin HY, et al. The associations between functional fitness test performance and abdominal obesity in healthy elderly people: results from the National Physical Fitness Examination Survey in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):264.

Lee PF, Ho CC, Yeh DP, Hung CT, Chang YC, Liu CC, et al. Cross-sectional associations of physical fitness performance level and sleep duration among older adults: results from the National Physical Fitness Survey in Taiwan. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(2):388.

Ho CC, Lee PF, Chen HL, Tseng CY, Hsieh XY, Chiu CH. Poor health-related physical fitness performance increases the overweight and obesity risk in older adults from Taiwan. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):170.

Mo H, Wo T. Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (R.O.C.). Annual Report of Health Promotion Administration. 2016. https://health99.hpa.gov.tw/storage/files/materials/21937.zip. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7(2):129–61.

Jonsson E, Seiger Å, Hirschfeld H. One-leg stance in healthy young and elderly adults: a measure of postural steadiness? Clin Biomech. 2004;19(7):688–94.

Voges MM, Giabbiconi CM, Schöne B, Waldorf M, Hartmann AS, Vocks S. Gender differences in body evaluation: do men show more self-serving double standards than women? Front Psychol. 2019;10:544.

Swainson MG, Batterham AM, Tsakirides C, Rutherford ZH, Hind K. Prediction of whole-body fat percentage and visceral adipose tissue mass from five anthropometric variables. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177175.

Sato T, Demura S, Murase T, Kobayashi Y. Estimation equation for the evaluation of the health status of middle-aged and elderly individuals based on the results of physical fitness tests: a proposal for use as an initial screening test. Human Performance Measure. 2009;6:1–9.

Angevaren M, Aufdemkampe G, Verhaar HJ, Aleman A, Vanhees L. Physical activity and enhanced fitness to improve cognitive function in older people without known cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD005381.

Elsawy B, Higgins KE. Physical activity guidelines for older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(1):55–9.

Nawrocka A, Mynarski W, Cholewa J. Adherence to physical activity guidelines and functional fitness of elderly women, using objective measurement. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24(4):632–5.

Acknowledgments

This study was based on data from the National Physical Fitness Survey in Taiwan provided by the Sports Cloud: Information and Application Research Center of Sports for All, Sport Administration, Ministry of Education in Taiwan. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Sport Administration, Ministry of Education in Taiwan.

Funding

This study was under three years of an integrated research project, which mainly supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (MOST 105–2627-M-030-002, 106–2627-M-030-002, 107–2627-M-030-002, 109–2410-H-030-059). The MOST provided financial supports, including the costs of the project. Besides, the cost of data analysis was supported by the Ministry of Education of Taiwan (FJU-A0108153).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJS and CCH participated in the design, conducted the statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. CTH supervised the study, assisted in data interpretation, and critically reviewed the manuscript. CL and PFL helped in conducting the study and revising the manuscript. CFL and HTC helped to manage and analyze the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Fu Jen Catholic University (FJU-IRB-C108088). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, YJ., Hsu, CT., Liang, C. et al. Association between health-related physical fitness and self-reported health status in older Taiwanese adults. BMC Geriatr 22, 235 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02929-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-022-02929-4