Abstract

Background

Caregiver burden affects the caregiver’s health and is related to the quality of care received by patients. This study aimed to determine the extent to which caregivers feel burdened when caring for patients with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and to investigate the predictors for caregiving burden.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted. One hundred two caregivers of patients with AD at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, a tertiary care hospital, were recruited. Assessment tools included the perceived stress scale (stress), PHQ-9 (depressive symptoms), Zarit Burden Interview-12 (burden), Clinical Dementia Rating (disease severity), Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaires (neuropsychiatric symptoms), and Barthel Activities Daily Living Index (dependency). The mediation analysis model was used to determine any associations.

Results

A higher level of severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms (r = 0.37, p < 0.01), higher level of perceived stress (r = 0.57, p < 0.01), and higher level of depressive symptoms (r = 0.54, p < 0.01) were related to a higher level of caregiver burden. The direct effect of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver burden was fully mediated by perceived stress and depressive symptoms (r = 0.13, p = 0.177), rendering an increase of 46% of variance in caregiver burden by this parallel mediation model. The significant indirect effect of neuropsychiatric symptoms by these two mediators was (r = 0.21, p = 0.001).

Conclusion

Caregiver burden is associated with patients’ neuropsychiatric symptoms indirectly through the caregiver’s depressive symptoms and perception of stress. Early detection and provision of appropriate interventions and skills to manage stress and depression could be useful in reducing and preventing caregiver burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) composes from 60 to 80% of dementia cases [1] and imposes a severe burden on patients themselves and their relatives. Caregiving for patients with AD could be related to high levels of strain. As dementia impairs the cognitive skills and functions of patients, it increases dependency and could influence the sense of burden among caregivers. This could affect the care quality received by patients, leading to complications and poor health outcomes [2]. Any intervention that could prevent or manage caregiver burden would be beneficial to the patient and family members [3].

Caregiver burden refers to the state in which one perceives physical and psychological well-being, financial status, and social relations could be threatened by care provision [4]. Related studies have reported possible predictors of caregiver burden including patient factors (e.g., changes in symptoms and severity of the psychological and behavioral problems), and caregiver factors (e.g., younger caregiver age, being female, lower educational levels), and lack of support [5,6,7,8].

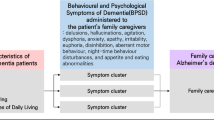

Neuropsychiatric symptoms or behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) have been found to create caregivers’ distress, burden, and burnout, and might be a predictive factor for caregiver decisions to institutionalize patients [9,10,11,12]. These symptoms include emotional, perceptual and behavioral disturbances [13]. Several studies have paid attention to the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and the level of caregiver burden [14, 15]. However, the evidence is inconclusive as to which types of BPSD influence caregiver well-being more than others [16].

Some studies have attempted to focus on which BPSD symptom has the greatest impact on caregiver burden and found inconsistent results due to the heterogeneity in measurement and analysis method. While practically every single symptom is important and accounted for caregiver burden and lack of well-being, the magnitude of the relationship between each neuropsychiatric symptom and caregiver burden may vary. What is lacking in most studies is a determination of what variables link neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden.

Research has shown that depression is a variable involved with both neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiving burden. Stress is also increased among caregivers [17,18,19]. In addition to the relationship between caregiving and depression, a significant relationship between perceived stress and depression has long been demonstrated in various settings. Evidence shows that perceived stress significantly correlated with higher scores in depressive symptoms [20,21,22,23]. It has been assumed that both perceived stress and depression would mediate the effect of neuropsychiatric symptoms on caregiver burden. To the best of our knowledge, this has not been investigated. This study aimed to investigate the associations between neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden and the mediating role of perceived stress and depressive symptoms. We hypothesized associations between neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden as described below (Fig. 1).

-

Hypothesis 1: Neuropsychiatric symptoms predict caregiver burden via depressive symptoms.

-

Hypothesis 2: Neuropsychiatric symptoms predict caregiver burden via perceived stress.

-

Hypothesis 3: Both depressive symptoms and perceived stress mediate the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms in predicting caregiver burden.

Methods

Participants and procedure

We surveyed caregivers of patients with AD treated by neurologists at Maharaj Nakorn Chiang Mai Hospital, a tertiary care hospital. We recruited primary caregivers aged 18 years or older who had been providing care for at least 1 month. The reason why we required the caregivers to provide care for at least 1 month to participate was that this duration would provide sufficient time for caregivers to know and be exposed to the patient’s symptoms and behaviors.

Inability to communicate, due to either language barrier or severe mental health problems, was criteria for exclusion. There were 127 patient/caregiver dyads invited to participate and 102 dyads were included for final analysis (Fig. 2). Caregivers were interviewed using a structured questionnaire to evaluate the patient’s status and to collect data including age, sex, occupation, highest level of education, relationship with patient and duration of care. The caregiver’s perception of the patients’ disease severity and functional performance were evaluated using Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaires (NPI-Q) and Barthel Activities Daily Living Index (ADL). The caregiver’s stress, depressive symptoms, quality of life and feeling of burden were determined using the Thai version of the perceived stress scale (PSS), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI-12). The caregivers provided written informed consent before completing the questionnaires, and provided consent on the patients’ behalf.

Measures

Measures about patients’ status

Clinical dementia rating (CDR)

CDR is a 5-point scale used to characterize 6 domains of cognitive and functional performance applicable to AD [24]. This includes memory, orientation, judgment and problem-solving ability, community affairs of the subject, home life, hobbies and personal care. It is based on a scale of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3 (from no cognitive impairment to severe cognitive impairment). The scores for each of the categories are weighted equally and summed to obtain a total score (0 to 18). Higher scores indicate greater severity of dementia. Translations of the CDR have been shown valid and reliable in Asian populations.

Neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaires (NPI-Q)

A structured interview of the caregiver is used to assess 12 behavior domains during the past month by asking whether the symptom is present (1 = yes, 0 = no) and how severe the symptom is (1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). The 12 domains include delusions, hallucinations, dysphoria, euphoria, anxiety, agitation, apathy, irritability, disinhibition, aberrant motor behavior, sleep and appetite/eating disorder [25].

Barthel activities daily living index (ADL)

The ADL is scored as 0 to 1, 2, or 3 in each of 10 basic domains including feeding, hygiene, transfer, toileting, ambulation, dressing, stairs, bathing and continence (stool and urine) [26]. Higher scores of ADL indicate better daily function.

Measures about caregivers

The Thai version of the 10-item perceived stress scale (PSS or T-PSS-10)

The PSS is a self-reporting, 10-item questionnaire measuring the extent to which individuals perceived stress [27]. The 5-response Likert scale ranges from 0 (never) to 4 (very often); the total scores range from 0 to 40. Higher scores indicate higher levels of perceived stress. This Thai version also shows good psychometric properties. The 2-factor structure model, namely, stress and control, fit well with the data in the confirmatory factor analysis study [28].

Patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

The PHQ-9 is a self-reporting, 9-item questionnaire measuring the extent to which an individual experienced depressive symptoms over the past 2 weeks [29]. The 4-response Likert scale ranges from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day); the total scores range from 0 to 27 and higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. The Thai version showed good psychometric properties [30].

The 12-item Zarit burden interview (ZBI-12)

The ZBI is a 12-item caregiver-reported questionnaire measuring the burden the respondent feels in providing care to the patient. Higher scores indicate a higher burden. The total score equals 17 [31]. This shortened, Thai version of the burden scale shows the ability to detect caregiver burden as a global score and is related to the 22-item version [32].

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses, such as sociodemographic data and all clinical variables, were presented as frequency, percentage and mean standard deviation. For mediation model analysis, we first conducted correlation analyses to assess the associations between all variables. Spearman’s rank correlation or Pearson’s correlation analysis were utilized as appropriate. To meet the assumption of the mediation model [33], a significant correlation (p < .05) between independent variables (NPI -Q score) and mediators (PHQ-9 score and PSS score), and dependent variables (ZBI score) would be expected. We then conducted a mediation model to test Hypothesis 1: that neuropsychiatric symptoms predict caregiver burden via depressive symptoms (Model 2). In Model 3, perceived stress was specified to mediate the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden, and in Model 4, depressive symptoms and perceived stress were specified as parallel mediators of the relationship between neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden. Despite the fact that a serial mediation model (M1 = perceived stress; M2 = depressive symptoms) could be an alternative as, theoretically, stress precedes depression, the sample size did not allow us to perform such a complex model (see supplement for power calculation). All models were conducted using Mplus, Version 8.0 with Maximum Likelihood estimation. To test the model fitness, a nonsignificant χ2 test; an RMSEA < 0.06; an SRMR < 0.08; a comparative fit index (CFI) and a Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.95 [34], were considered a good model fit. Indirect effects were tested using bootstrap estimation with 5000 samples. Bias-corrected percentile bootstrap confidence intervals were reported at the 95% confidence level. All diagrams were drawn using AMOS version 18.

Results

One hundred two patients together with their caregivers were recruited in the study including 72 female patients (70.6%) with a mean age of 79.4 years (SD 7.9). The average ADL score was 15.4 (SD 6.5) and all patients had at least one symptom of BPSD (mean 5.8, SD 2.6). The average age of caregivers was 55.0 (SD 12.9). Most caregivers in our sample group were educated, female (77.5%), and without financial problems. About half reported physical problems. Most caregivers were a child of the patient (68.6%). The average duration of care of the patient was 6.1 years (SD 8.7), which indicated the presence of outliers. Concerning the outliers, we have analyzed the correlation between ZBI and duration of caregiving both with original data and data without outliers, and the results were shown to be the same - without significance. The average time spent taking care of the patient was 15.4 h daily (SD 8.1) and most patients had at least one helper. About 16% reported having severe burden. The demographic data of the patients and caregivers are described in Table 1.

Table 2 shows that no sociodemographic variables, CDR and ADL were significantly related to ZBI, but to PSS, PHQ-9 and NPI. Significant correlations were observed between PHQ-9, ZBI, PSS, and NPI, denoting that the mediation model among these 4 variables was justified.

Table 3 shows the results of the mediation model after accounting for sex, age, education, CDR and ADL. Model 0 was used to test the association between NPI and ZBI. The model fit statistics suggested that the model fit the data, χ2 = 28.354, df = 11, p = 0.0029, CF =1.000, TLI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.000. NPI explained 17.8% of caregiver burden. Model 2 tested hypothesis 1 in that PHQ-9 was added to the model. The model fit statistics suggested that the model fit the data, χ2 = 76.372, df = 18, p < 0.001; CFI =1.000, TLI =1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.000. The overall model explained 36.6% of the variance in caregiver burden. Model 3, tested hypothesis 2 in that PSS was added to the model. The model fit statistics suggested that the model fit the data, χ2 = 76.947, df = 18, p < 0.001; CFI =1.000, TLI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.000. Compared with Model 1, the direct effect of NPI was reduced to 0.179, and was nonsignificant. The overall model explained 39.3% of the variance in caregiver burden. Model 4, tested hypothesis 3 in that both PSS and PHQ-9 were added to the parallel model. The model fit statistics suggested that the model fit the data, χ2 = 129.408, df = 26, p < 0.001; CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.000, RMSEA = 0.000, SRMR = 0.000. Notably, the effect of PSS was stronger than that of PHQ-9; both nullified the direct effect of NPI. The overall model explained 45.9% of the variance in caregiver burden.

Discussion

The present study aimed to demonstrate to what extent caregiver burden was influenced by neuropsychiatric symptoms. The patient’s neuropsychiatric behavioral symptoms were associated with the feeling of burden reported by the caregiver. This result is concurrent with many studies [9, 15, 35,36,37]. However, by adding depressive symptoms and perceived stress, the feeling of burden could be more fully explained while reducing the direct effect of neuropsychiatric symptoms to nonsignificance.

This indicated that a feeling of burden comes from many sources. Whatever the source is, it entails experiencing stress and depressive symptoms in the caregiver. The fact that depressive symptoms and perceived stress fully mediated the relationship with the severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms may indicate that depressive symptoms and perceived stress are more proximal to caregiver burden than the patient’s symptoms. By including depressive symptoms and perceived stress in the parallel mediation model, the variance of caregiver burden was explained up to 28%. These findings were consistent with related studies that show the caregiver’s factor plays an important role, especially concerning depression [38, 39].

Our findings were also supported by Wang and colleagues, in that depression had a significantly direct effect on caregiver burden. They also found that the relationship could be moderated by perceived social support [40], while other research found it could be mediated by a positive attitude concerning caregiving [41].

Notably, those findings, including ours, have been observed in Asian samples, which might differ from studies conducted in a Western culture, where caregiving activity may not be provided mostly by family members or relatives. As noted by Yu et al., in Chinese culture (comparable to Thai culture), caring for parents is considered the role and responsibility of family members. In addition to social support, they found that family function and caregiving experience were mediators of the relationship between the patient’s factors, e.g., cognitive level, physical function behavioral problems and caregiver burden [42]. However, similar findings were found in non-Asian cultures as well, in that the caregiver’s age and type of relationship showed a higher impact on the neuropsychiatric symptoms and caregiver burden [38, 39].

Does the effect size of perceived stress over depression on caregiver burden matter clinically? We have known that perceived stress could lead to depression, and vice versa [43,44,45]. Perceived stress is considered a predetermined psychological state before experiencing depression. Perceived stress should then become a target for early identification in managing caregiving problems. As mentioned earlier, the serial mediation model, in which perceived stress has a direct effect on depressive symptoms, should be proposed and tested if the sample size is sufficient. Despite the fact that the sample size was relatively small, it exhibited sufficient statistical power (≥80%) for each parameter. However, it did not support the case for the serial mediation model, which requires up to 280 participants (see supplement file).

Interestingly, our results showed that perceived stress was related to caregiver’s education and age. Individuals with a younger age, but a higher level of education, tend to feel more stressed in providing care to patients with AD, while depression was associated with the patient’s symptoms, such as the severity of the dementia and the ability to help oneself. These interesting relationships are not fully clear to us and need further investigation. However, the fact that perceived stress overshadowed depression and makes patient’s factors seem less significant could be explained by its proximity between perceived stress and burden, and variances shared by the same respondent.

Therefore, to prevent caregiver burden, identifying and managing these two mental health problems could prove useful. While physicians assess the severity and progression of the disease, the perception of the caregiver should be simultaneously assessed. When the caregiver feels stress, difficulty in controlling neuropsychiatric symptoms of the patient, or other problems, then caregiver training could be useful. Studies also revealed an association in the opposite direction: caregiver burden might affect patient behaviors. Inappropriate caregiver management strategies, such as confronting or ignoring the patient, or poor patient-caregiver interaction may trigger dementia in patients’ behaviors [46]. Effective treatment could include both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies. Nonpharmacological interventions to reduce patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms include music therapy, touch therapy, bright light therapy, cognitive rehabilitation, etc. However, indications for each intervention could vary depending on the type of neuropsychiatric symptom. Caregiver training, especially among younger people, should include educating and supporting the caregiver to handle those symptoms and use appropriate coping skills. A recent study of systematic review and meta-analysis showed that interventions including emotional support, exercise, and education/skills-based training on coping strategies and dealing with patient behaviors, trended to relieve caregiver burden. This was especially evident when the interventions consisted of multicomponent content. These interventions would reduce stress or depression, and ultimately reduce the feeling of burden [47,48,49,50].

The strengths of the present study are that it focused on patients with AD and their primary caregivers. Caregivers who participated in the study were selected as a key primary caregiver who would be most affected by the patient. However, some limitations were encountered. Firstly, the study recruited participants from a tertiary care hospital which would not represent caregivers and patients with AD being treated elsewhere. Secondly, according to the nature of the cross-sectional study design, a causal relationship could not be evaluated. Thirdly, a caregiver’s depressed mood or presenting mental disorder during the interview could have led to information bias, as any abnormal judgment stemming from the mental disorder would interfere with the analysis. This group would be associated with more feelings of burden, so this could have resulted in an underestimated prevalence. Thus, initially in the analysis plan, we have endeavored to minimize this effect by excluding caregivers with a severe mental disorder from the study. However, such cases were not found during the recruitment so this would not have affected the results. Fourthly, family function is important, especially in Asian culture, and may have an impact on the feelings of burden. Unfortunately, we did not collect such specific information. Lastly, the small sample size precludes us from testing a more specific model determining the direct effect of perceived stress on depressive symptoms, i.e. a serial mediation model. In conclusion, caregiver burden could not be neglected when taking care of patients with AD. Caregiver’s feeling of burden concerning the patient’s neuropsychiatric symptoms is indirectly associated with the caregiver’s perception of stress and feeling of depression. Apart from controlling patients’ symptoms, early detection and providing psychological support, effective intervention and appropriate emotional management to the caregivers would provide benefit in reducing and preventing caregiver burden.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s Disease

- ADL:

-

Activities Daily Living

- CDR:

-

Clinical Dementia Rating

- NPI:

-

Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaires

- PHQ-9:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- PSS:

-

Perceived Stress Scale

- ZBI:

-

Zarit Burden Interview

References

Barker WW, Luis CA, Kashuba A, Luis M, Harwood DG, Loewenstein D, Waters C, Jimison P, Shepherd E, Sevush S, et al. Relative frequencies of Alzheimer disease, Lewy body, vascular and frontotemporal dementia, and hippocampal sclerosis in the State of Florida Brain Bank. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002;16:203–12.

Kuzuya M, Enoki H, Hasegawa J, Izawa S, Hirakawa Y, Shimokata H, Akihisa I. Impact of caregiver burden on adverse health outcomes in community-dwelling dependent older care recipients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(4):382–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181e9b98d.

Chan SW. Family caregiving in dementia: the Asian perspective of a global problem. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30(6):469–78. https://doi.org/10.1159/000322086.

Sherman CW, Burgio LD, Kowalkowski JD. Chapter 10 - Assessment of Dementia Family Caregivers. In: Lichtenberg PA, editor. Handbook of Assessment in Clinical Gerontology. 2nd ed. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. p. 243–71.

Mohamed S, Rosenheck R, Lyketsos K, Schneider LS. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: cross sectional and longitudinal patient correlates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(10):917–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d5745d.

Gallicchio L, Siddiqi N, Langenberg P, Baumgarten M. Gender differences in burden and depression among informal caregivers of demented elders in the community. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(2):154–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.538.

Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Barnes DE, Newcomer RJ, Yaffe K. Caregiver characteristics are associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):796–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00697.x.

Clyburn LD, Stones MJ, Hadjistavropoulos T, Tuokko H. Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2000;55:S2–13.

Cheng S-T. Dementia caregiver burden: a research update and critical analysis. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19(9):64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2.

Chen CT, Chang C-C, Chang W-N, Tsai N-W, Huang C-C, Chang Y-T, Wang H-C, Kung C-T, Su Y-J, Lin W-C, Cheng BC, Su CM, Hsiao SY, Hsu CW, Lu CH. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: associations with caregiver burden and treatment outcomes. QJM. 2017;110(9):565–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcx077.

Mukherjee A, Biswas A, Roy A, Biswas S, Gangopadhyay G, Das SK. Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: correlates and impact on caregiver distress. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2017;7(3):354–65. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481568.

Torrisi M, De Cola MC, Marra A, De Luca R, Bramanti P, Calabrò RS. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia may predict caregiver burden: a Sicilian exploratory study. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(2):103–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12197.

Cloak N, Al Khalili Y. Behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2020, StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2020.

Terum TM, Andersen JR, Rongve A, Aarsland D, Svendsboe EJ, Testad I. The relationship of specific items on the neuropsychiatric inventory to caregiver burden in dementia: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(7):703–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4704.

Shim SH, Kang HS, Kim JH, Kim DK. Factors associated with caregiver burden in dementia: 1-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(1):43–9. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2016.13.1.43.

Feast A, Moniz-Cook E, Stoner C, Charlesworth G, Orrell M. A systematic review of the relationship between behavioral and psychological symptoms (BPSD) and caregiver well-being. Int Psychogeriatr. 2016;28(11):1761–74. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000922.

Cheng ST, Lam LC, Kwok T. Neuropsychiatric symptom clusters of Alzheimer disease in Hong Kong Chinese: correlates with caregiver burden and depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(10):1029–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.041.

Baharudin AD, Din NC, Subramaniam P, Razali R. The associations between behavioral-psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and coping strategy, burden of care and personality style among low-income caregivers of patients with dementia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(S4):447. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6868-0.

Luchesi BM, Souza ÉN, Gratão AC, Gomes GA, Inouye K, Alexandre Tda S, Marques S, Pavarini SC. The evaluation of perceived stress and associated factors in elderly caregivers. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;67:7–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.06.017.

Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):P112–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.2.P112.

Jiang JM, Seng EK, Zimmerman ME, Sliwinski M, Kim M, Lipton RB. Evaluation of the reliability, validity, and predictive validity of the subscales of the perceived stress scale in older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(3):987–96. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170289.

Banjongrewadee M, Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Pipanmekaporn T, Punjasawadwong Y, Mueankwan S. The role of perceived stress and cognitive function on the relationship between neuroticism and depression among the elderly: a structural equation model approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2440-9.

Pereira-Morales AJ, Adan A, Forero DA. Perceived stress as a mediator of the relationship between neuroticism and depression and anxiety symptoms. Curr Psychol. 2019;38(1):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9587-7.

Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–4. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.43.11.2412-a.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, Bray T, Castellon S, Masterman D, MacMillan A, Ketchel P, DeKosky ST. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the neuropsychiatric inventory caregiver distress scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(2):210–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02542.x.

Saisana M. Barthel Index. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Edited by Michalos AC. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2014:325–6.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T. The Thai version of the PSS-10: an investigation of its psychometric properties. Biopsychosoc Med. 2010;4(1):6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-4-6.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x.

Lotrakul M, Sumrithe S, Saipanish R. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the PHQ-9. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8(1):46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-8-46.

Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O'Donnell M. The Zarit burden interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.5.652.

Pinyopornpanish K, Pinyopornpanish M, Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Soontornpun A, Kuntawong P. Investigating psychometric properties of the Thai version of the Zarit burden interview using rasch model and confirmatory factor analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2020;13(1):120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-04967-w.

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173.

Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Lou Q, Liu S, Huo YR, Liu M, Liu S, Ji Y. Comprehensive analysis of patient and caregiver predictors for caregiver burden, anxiety and depression in Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24(17-18):2668–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12870.

Ransmayr G, Hermann P, Sallinger K, Benke T, Seiler S, Dal-Bianco P, Marksteiner J, Defrancesco M, Sanin G, Struhal W, Guger M, Vosko M, Hagenauer K, Lehner R, Futschik A, Schmidt R. Caregiving and caregiver burden in dementia home care: results from the prospective dementia registry (PRODEM) of the Austrian Alzheimer Society. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(1):103–14. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170657.

Connors MH, Seeher K, Teixeira-Pinto A, Woodward M, Ames D, Brodaty H. Dementia and caregiver burden: a three-year longitudinal study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(2):250–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5244.

Gonyea J, O'Connor M, Carruth A, Boyle P. Subjective appraisal of Alzheimer’s disease caregiving: the role of self-efficacy and depressive symptoms in the experience of burden. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2005;20(5):273–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331750502000505.

Rinaldi P, Spazzafumo L, Mastriforti R, Mattioli P, Marvardi M, Polidori MC, Cherubini A, Abate G, Bartorelli L, Bonaiuto S, Capurso A, Cucinotta D, Gallucci M, Giordano M, Martorelli M, Masaraki G, Nieddu A, Pettenati C, Putzu P, Tammaro VA, Tomassini PF, Vergani C, Senin U, Mecocci P, Study Group on Brain Aging of the Italian Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (GSIC-SIGG). Predictors of high level of burden and distress in caregivers of demented patients: results of an Italian multicenter study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(2):168–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1267.

Wang Z, Ma C, Han H, He R, Zhou L, Liang R, Yu H. Caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: moderation effects of social support and mediation effects of positive aspects of caregiving. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(9):1198–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4910.

Xue H, Zhai J, He R, Zhou L, Liang R, Yu H. Moderating role of positive aspects of caregiving in the relationship between depression in persons with Alzheimer’s disease and caregiver burden. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:400–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.088.

Yu H, Wang X, He R, Liang R, Zhou L. Measuring the caregiver burden of caring for community-residing people with Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0132168. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132168.

Deeken F, Häusler A, Nordheim J, Rapp M, Knoll N, Rieckmann N. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in a sample of German dementia patients and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(1):39–47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217001387.

Clawson AH, Borrelli B, McQuaid EL, Dunsiger S. The role of caregiver social support, depressed mood, and perceived stress in changes in pediatric secondhand smoke exposure and asthma functional morbidity following an asthma exacerbation. Health Psychol. 2016;35(6):541–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000318.

Koyanagi A, DeVylder JE, Stubbs B, Carvalho AF, Veronese N, Haro JM, Santini ZI. Depression, sleep problems, and perceived stress among informal caregivers in 58 low-, middle-, and high-income countries: a cross-sectional analysis of community-based surveys. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;96:115–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.001.

de Vugt ME, Stevens F, Aalten P, Lousberg R, Jaspers N, Winkens I, Jolles J, Verhey FR. Do caregiver management strategies influence patient behaviour in dementia? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):85–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1044.

Springate BA, Tremont G. Dimensions of caregiver burden in dementia: impact of demographic, mood, and care recipient variables. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(3):294–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.09.006.

Shaji KS, George RK, Prince MJ, Jacob KS. Behavioral symptoms and caregiver burden in dementia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51(1):45–9. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.44905.

Pahlavanzadeh S, Heidari FG, Maghsudi J, Ghazavi Z, Samandari S. The effects of family education program on the caregiver burden of families of elderly with dementia disorders. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2010;15(3):102–8.

Navidian A, Kermansaravi F, Rigi SN. The effectiveness of a group psycho-educational program on family caregiver burden of patients with mental disorders. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5(1):399. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-5-399.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the patients and caregivers for their participation and encouragement for us to conduct this research.

Funding

This research was supported by the Research Medical Fund, Grant Number 066-2561, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP, KP, AS, ST, NW and TW participated in the concept and design of the study. MP, AS, ST, and AN collected data. KP, NW, and TW performed the statistical analyses. MP, AS, TW, and KP drafted and edited the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to interpret data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (PSY-2560-05110). All patients provided written informed consent to the study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication is not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pinyopornpanish, M., Pinyopornpanish, K., Soontornpun, A. et al. Perceived stress and depressive symptoms not neuropsychiatric symptoms predict caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 21, 180 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02136-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02136-7