Abstract

Background

While the field of rehabilitation has determined a common definition of professional practice, legislators and healthcare professionals in various Western countries have struggled to reach consensus about how the newer offer of ‘reablement’ should be organised, operationalised, and understood as a health service for older adults. International research indicates that there is confusion, ambiguity, and disagreement about the terminology and the structure of these programmes, and they may not be adequately supporting older people’s self-identified goals. Could an analysis of the concept’s genealogy illuminate how reablement can be more effective and beneficial in theory and in practice?

Methods

We conducted a qualitative and quantitative scoping review to determine how reablement has developed through time and space. Eligible articles (N=86) had to focus on any of the defined features of current reablement programmes; there were no restrictions on study designs or publication dates. In articles published from 1947 to 2019, we identified themes and patterns, commonalities, and differences in how various countries described and defined reablement. We also performed an analysis using computer software to construct and visualise term maps based on significant words extracted from the article abstracts.

Results

The fundamental principles of reablement have a long history. However, these programmes have undergone a widespread expansion since the mid-2000s with an intention to reduce costs related to providing long-term care services and in-home assistance to growing older populations. Despite theoretical aspirations to offer person-centred and goal-directed reablement, few countries have been able to implement programmes that adequately promote older people’s goals, social involvement, or participation in their local community in a safe, culturally sensitive and adaptable way.

Conclusions

Reablement is meant to support older people in attaining their self-defined goals to be both more physically independent at home and socially involved in their communities. However, until legislators, health professionals, and older people can collectively reach consensus about how person-centred reablement can be more effectively implemented and supported in professional home-care practice, it will be difficult to determine a conceptual description of reablement as a service that is unique, separate, and distinct from standard rehabilitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

Population ageing raises significant questions about the socio-economic sustainability of increased human longevity, and this demographic shift has resulted in the promotion of ‘healthy ageing’ in many Western societies. While there is no universally accepted definition for ‘healthy ageing’ – or active, productive, or successful ageing – such concepts typically refer to individual or collective strategies used to optimise economic, social, and cultural participation throughout the life course [1]. The paradigm of ‘healthy ageing’ is often emphasised in legislation and social policies that target older people [2,3,4,5], particularly in high-income, industrialised Western societies that tend to valorise individualism and productivity. For example, during the International Federation on Ageing (IFA) Global Think Tank and Copenhagen Summit 2015/2016, attendees from many of these countries met to discuss ways to develop a solution-driven global public-health agenda that would further promote ‘healthy ageing’. One result of the summit was an agreed intention to advance “improved awareness of the value of a reablement approach and applied technology for an increasing ageing population” [6]. Here, reablement for the individual older person was defined as “an active process of (re) gaining skills and confidence in maintaining or improving function, or adapting to the consequences of declining function. It also supports the individual to remain socially engaged within the community context in a safe, culturally sensitive and adaptable way” [6].

Although this definition may seem straightforward, it is not universally accepted. This is because the concept of ‘reablement’ is relatively new and lacks regulation; thus, it is generally considered to be “poorly defined, with little understanding of what it looks like when achieved” [7]. Furthermore, while the related field of physical rehabilitation has long had a conceptual description to “foster the development of a common understanding of rehabilitation and its professions” [8], it appears that legislators and healthcare professionals both within and across various Western countries have been struggling to reach consensus about how reablement programmes should be defined, described, and structured. As such, there is ambiguity about what reablement is, what these programmes offer, and why (e.g., some may not specifically target older people; most are defined as being time-limited and home-based) as well as how reablement can best promote ‘healthy ageing’. Could an analysis of the concept’s genealogy illuminate how reablement can be more effective in both theory and in practice to benefit older people?

We performed a quantitative and qualitative exploration of how the concept of ‘reablement’ has developed over time in various countries to examine the common features and differences between these programmes at an international level. With our investigation of the term’s genealogy, this scoping review contributes insights and provides clarity to legislators, health professionals, and older people with regards to how these programmes can be organised, operationalised, and understood in practice – fundamentally, this clarification will enable them to collectively determine what ‘reablement’ looks like when it is achieved.

Methods

On 25 March 2019, we searched Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycInfo for all articles on reablement. There were no restrictions on publication dates. Due to the exploratory nature of our study and our main interest in reablement, the search term for all databases was “reablement OR re-ablement”. This resulted in papers published in English by researchers primarily working in high-income Western countries (as defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, International Monetary Fund, World Health Organization, and the United Nations). We examined the full texts of potentially eligible articles, and then used reference tracking to scrutinise reviews, updates, and protocols for additional potentially eligible articles.

Article selection

Two authors (AC and SK) jointly examined all resulting articles for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third reviewer (RGJW). For an article to be eligible, it had to focus on any of the most common aspects of ‘reablement’ as currently defined by most local government officials or health- or aged-care organisations:

-

time-limited offer

-

home-based intervention

-

intervention implemented to improve a person’s functional ability and improve or develop their social participation (i.e., to support them in being more socially active).

The resulting original contribution had to be a complete research article, study protocol, or editorial published in an academic journal or book, and therefore not a conference abstract or poster. We did not apply restrictions on study designs (quantitative or qualitative) or publication dates.

Qualitative analysis of the eligible articles

Starting with the earliest articles published, we examined the titles and abstracts for themes and patterns, commonalities, and differences in how ‘reablement’ was described and defined. In order to inform our analysis, we aimed to identify several shifts in terms of how reablement programmes have developed, which components they share, how reablement is organised and delivered as a service model, and how/why reablement is offered by healthcare authorities and to whom. This thematic analysis provided flexibility and allowed us to manage a large initial dataset; it was also an efficient way for us to determine the conceptual shifts in how reablement programmes have developed over time. Once we determined these predominant themes and patterns, we reviewed all of the relevant articles in full.

Quantitative analysis of the eligible articles

To validate the findings from our qualitative analysis, we also performed a quantitative analysis of the eligible articles using VOS viewer software version 1.6.11 [9]. Here, we used the software’s text-mining functions to construct and visualise term maps based on scientific terms extracted from the eligible abstracts. A term map is a two-dimensional visualisation that represents networks of concurrent relations between scientific terms. The relatedness of terms is determined based on two or more terms occurring together in the abstracts. The smaller the distance between two terms, the stronger the terms are correlated with each other. Multiple terms with high co-occurrence are grouped together into clusters, and each cluster can therefore be seen as a confined intellectual topic. We used a full counting method, meaning that the number of occurrences of a term in a document was taken into account instead of only looking at the presence or absence of a term. Parts of the texts were tagged to identify verbs, nouns, adjectives, etc., and thereafter a filter selected all word sequences that consisted exclusively of nouns and adjectives. We also set a threshold of minimum five occurrences for a term to be included in our analysis. Out of all of the terms included, a relevance score was calculated and, based on this score, the most relevant terms were selected. The top 60% of the most relevant terms were visualised and coloured according to publication year. It is likely that some of the terms may appear across multiple time periods. However, each term is only visualised once, depending on the average publication year of articles in which the term was mentioned.

Results

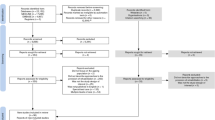

Figure 1 presents a flow chart describing the selection of articles. Out of the 120 articles identified in our initial search in Medline, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycInfo databases, 14 were conference abstracts, 14 were beyond the scope and therefore irrelevant (e.g., articles on postnatal wards, homeless people, non-humans, etc.), and 18 were hospital-based post-disease/ -injury, which resulted in 74 relevant articles from the database search. We added another 12 relevant articles from reference tracking for a total of 86 eligible articles that were appropriate for the next stage of quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Qualitative analysis

Based on the collected literature, we divided the conceptual shifts about reablement into the following categories: historical focus (pre-2000); the emergence of ‘restorative care’ for older people (2001–2005); the transition from ‘restorative care’ to ‘reablement’ (2006–2014); and the boom of reablement services (2015–2019).

Historical focus (pre-2000)

Our literature review indicated that the meaning and conceptualisation of ‘reablement’ has changed since the beginning of the twentieth century; in practice, it has both run parallel to and deviated from its sister practice, rehabilitation. Notably, after World War II, the emphasis of clinical rehabilitation began to broaden from a patient’s recovery of ambulation to a focus on “the comprehensive restoration of an individual’s physical, mental, emotional, vocational, and social capacities” [10, 11]. Around the same time, the word ‘reablement’ first entered the scholarly lexicon in an editorial published in Physiotherapy that was simply titled “Disablement and reablement” [12]. The author argued that the word ‘rehabilitation’ must be discarded in favour of ‘reablement’, which should focus on “making a disabled person able-bodied again” and restoring “a man to capacity for his former work, or, alternatively, what particular work he can be trained for” [12].

The publication of this editorial at the end of World War II suggests that the author’s conceptualisation of reablement was inspired by the need to support and train ‘dis-abled’ patients – most likely injured soldiers returning from the frontlines – in restoring their functional abilities and ‘re-settling’ them both at home and in the workplace. The term ‘reablement’ also started to be used to describe physiotherapeutic training for patients suffering from specific health conditions or diseases, such as cerebral palsy and rheumatoid arthritis [13, 14]. The first mention of reablement associated with “the heavily handicapped patient” was found in the title of a British journal article on the principles of rehabilitation in 1962 [15], and an article from 1975 discussed reablement in relation to functional activities and “resettlement in work and home” [16].

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, there was a continued emphasis on the restoration of functional ability and “resettlement in work and home” [17,18,19] as well as ‘re-abling’ patients suffering from arthritis and other rheumatic diseases [20]. Few scholarly articles published in the 1980s and 1990s mentioned the term ‘reablement’, but a 1994 editorial in Reviews in Clinical Gerontology was the first to mention a focus on older people: “‘We are trying to improve this patient’s quality of life’ is the often stated goal of much therapeutic effort made for elderly people” [21], continuing that “the criteria for successful rehabilitation are often limited to independence in a limited range of basic activities of daily living. Reablement is most obviously concerned with reducing disability and the appropriate outcomes must be disability measures. ‘Resettlement’ is a more complex goal and implies the restoration of people to their own, or sometimes a new, environment” [21]. This article suggests that the term ‘reablement’ was still linked to ‘rehabilitation’ while ‘resettlement’ was understood as a different approach that included a focus on the environmental ‘restoration’ of older people.

The emergence of ‘restorative care’ for older people (2001–2005)

By the turn of the millennium, this idea of ‘resettlement’ and ‘restoration’ as a specific intervention for older people receiving homecare had transitioned into ‘restorative care’. In 2002, Tinetti et al. published what could be considered a landmark paper in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) titled: “Evaluation of restorative care vs usual care for older adults receiving an acute episode of home care”. The authors suggest that “a primary goal of health care for older, particularly multiply and chronically ill, persons should be to optimize function and comfort rather than solely to treat individual diseases” [22]. The restorative-care model that the authors described was based on principles adapted from geriatric medicine, nursing, rehabilitation, and goal attainment, which refers to the belief that people “are more likely to adhere to treatment plans if they are involved in setting goals and in determining the process for meeting these goals” [22].

The intervention included training relevant health professionals (i.e., homecare nurses, therapists, and home health aides) as well as reorganising this home-care staff “from individual care providers into an integrated, coordinated, interdisciplinary team with shared goals”, which required a “reorientation of the focus of the homecare team from primarily treating diseases and ‘taking care of’ patients toward working together to maximize function and comfort” [22]. Furthermore, it was built upon “the establishment of goals based on input from the patient, family, and home care staff, and agreement among this group on the process for reaching these goals” [22].

Although the authors cite several studies from the 1990s that focused on goal-setting in clinical medicine for the so-called ‘frail elderly’, this intervention appears to be the first well-defined programme that reflects the central aims of reablement as it is presently being operationalised and implemented worldwide; in other words, while the restorative-care model was not explicitly called ‘reablement’, it contained similar features and aims, and seems to have provided the philosophical foundation for many of today’s reablement programmes. Tinetti et al.’s research also built its findings on the authors’ earlier study, “The design and implementation of a restorative care model for home care” [23] as well as several previous articles that examined older people’s self-care and functionality with regards to performing activities of daily living (ADLs) in both hospital and home settings.

During this period, researchers in the United Kingdom also published a report that described 33 services that were part of the NHS Modernisation Agency’s Changing Workforce Programme project [24]. These services were “designed to prevent inappropriate hospital admissions, facilitate hospital discharge, and prevent premature or avoidable admissions to long-term care” [24] – and this included what the authors called ‘reablement services’. The summary of care roles outlines that this service focuses on providing “personal care, daily living skills, mobility and financial management (…); enablement rather than ‘doing’ for their services users; dedicated home workers providing personal care from an enabling perspective with rehabilitation skills; reablement to promote independence” [24].

The transition from ‘restorative care’ to ‘reablement’ (2006–2014)

The foundational aims of ‘restorative care’ services for older people seem to have transitioned to being called ‘reablement’ more broadly in the late-2000s, and our search identified 24 relevant articles from this time period. In the United Kingdom, this transition was reinforced by a retrospective longitudinal study of ‘homecare re-ablement’, “Research into the longer-term effects of reablement services” [25], which was undertaken for the Care Services Efficiency Delivery (CSED) Programme at the Department of Health. In the Journal of Integrated Care, it was stated that homecare reablement had been widely accepted in the UK, and referred to “services for people with poor physical or mental health to help them accommodate their illness by learning or re-learning the skills necessary for daily living” [26].

Other British researchers emphasised progress in developing “outcomes-focused services for older people and the factors that help and hinder this” [27]. The authors also described two small-scale, exploratory studies that examined the impact of home-care reablement on subsequent service use [28]. These articles distinguish ‘reablement’ as its own unique approach, describing it as a service that “aims to help people ‘do things for themselves’, rather than ‘having things done for them’. Home care reablement services therefore provide personal care, help with mobility and other practical tasks for a time-limited period” [28]. The authors further stated that user-identified outcomes are central to the reablement process, particularly with regards to personal care, daily living tasks, or social activities. They also pointed out that reablement services can be offered to adults of all ages in the UK, although they suggested that “even very elderly…users may regain skills and attitudes to help sustain them for a relatively long period” [28]. The same authors published a prospective longitudinal study and working paper that investigated the longer-term impacts of “home care re-ablement services” [29].

During this time period, a greater focus on professional practice was beginning to develop [30], and a professional column in British Journal of Community Nursing stated that reablement is “generally provided by local authorities as part of adult social care provision with a focus upon promoting self-care skills and rebuilding confidence” [31]. Reablement services targeted specifically at older people was also beginning to emerge in northern Europe – particularly, Finland. However, such programmes were termed “geriatric rehabilitation’ [32] and did not take place within the home setting. But, other than this difference, the Finnish intervention had aims similar to other reablement programmes; e.g., the goal was “to achieve and maintain functional independence, and to enable older people to remain community-dwelling” [32].

By 2011, British experts reiterated the burgeoning ‘reablement philosophy’, which states that “the focus is on restoring independent functioning rather than resolving health care issues, and on helping people to do things for themselves rather than the traditional home care approach of doing things for people that they cannot do for themselves” [33]. Other researchers claimed that “home-care re-ablement or ‘restorative’ services” should enable older people to live independently in the community, writing that “the assumption underlying re-ablement is that enhancing independence and practical skills reduces needs for ongoing service support” [34]. However, there remained a lack of consensus about the definition, organisation, and practices related to the overall concept of reablement. For example, a 2011 Taiwanese article discussed community hospital-based post-acute care (PAC) to improve functional ability amongst frail older patients [35], which appears to be the first time East Asian researchers mention the term.

A 2012 British article – which claimed to be the first in-depth study of the experiences of home-care reablement service users and carers – described reablement as “a short-term, intensive service that helps people to (re-) establish their capacity and confidence in performing basic personal care and domestic tasks at home, thereby reducing needs for longer term help” [36]. The authors noted that similar programmes were also being implemented in Australia and New Zealand. In Australia, the term ‘restorative care’ was being used to describe interventions with aims similar to many current reablement programmes. For example, the provision and nature of home-care services had developed a “new focus on activity, independence and successful ageing” and concluded that “a restorative approach to home care has significant advantages over the traditional approach aimed at maintenance and support only” [37]. However, the National Development Manager–Care and Communities for Age UK argued that reablement is “nowhere near as effective as it could be” because it lacks personalisation and “fails to appreciate what motivates people to make the substantial effort involved in regaining lost skills and abilities” [38].

By 2013, Australian researchers began to describe restorative home-care services as “short-term and aimed at maximizing a person’s ability to live independently. They are multidimensional and often include an exercise program to improve strength, mobility, and balance” and “the intervention should ultimately “create independence, improve self-image and self-esteem, and reduce the level of care required through the delivery of an individualized program” [39]. The linguistic transition from ‘restorative care’ to ‘reablement’ in Australia is clearly seen in a study that aimed “to determine whether older individuals who participated in a reablement (restorative) program rather than immediately receiving conventional home care services had a reduced need for ongoing support and lower home care costs” [40]. These authors also provided a straightforward definition of reablement in Australia; i.e., “an emphasis on capacity building (…) to maintain or promote a client’s capacity to live as independently as possible, with an aim of improving functional independence, quality of life, and social participation, (…and) an emphasis on a holistic, person-centered approach to care, which promotes clients’ wellness and active participation in decisions about care” [40].

However, it appears that a semantic debate was still occurring in Ireland and the UK. An Irish intervention protocol described ‘reablement’ (in scare-quotes) as “an innovative approach to improving home-care services for older adults in need of care and support or at risk of functional decline” [41], and the authors identified five essential defining criteria for an intervention to be called ‘reablement’: 1. participants must have an identified need for formal care and support, or are at risk of functional decline; 2. the intervention must be time-limited (typically 6–12 weeks) and intensive (e.g., multiple home visits); 3. the intervention must be delivered in the older person’s own home; 4. the intervention must focus on maximising independence; and 5. the intervention must be person-centred and goal-directed [41]. A 2013 British article described such programmes as “re-ablement or restorative homecare services that provide time-limited input aimed at reducing dependency in personal activities of daily living, and preventing or delaying the need for further homecare support” [42] while a 2014 Australian paper made the distinction between terminology in the different countries: “Restorative home-care services, or re-ablement home-care services as they are now known in the UK, aim to assist older individuals who are experiencing difficulties in everyday living to optimise their functioning and reduce their need for ongoing home care” [43].

Nearly all of the articles during this time period also cite a growing political interest in cost-savings. For example, although the emphasis in the UK remained on providing services to adults of all ages (not specifically older adults), the white paper, Caring for Our Future: Reforming Care and Support, provided a definition of reablement in which “users receive homecare but are supported to increase their ability to manage tasks independently, in order to reduce the amount of homecare they will require in the longer term” [44]. The authors further distinguished reablement from rehabilitation, stating that reablement services “adopt a social model of recovery rather than a medical model” [44]. During this time, there is also increased emphasis on developing professional practice; e.g., a critical literature review analysed evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of occupational therapy interventions for older people in social-care services, including rehabilitation and reablement [45].

In Scandinavia, reablement programmes started to be offered in the 2000s; the first was established in Östersund Municipality, Sweden, in 1999 and – inspired by the Swedes’ positive experiences – soon began to develop in neighbouring Denmark (2008) and Norway (2012) under different names. The study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of reablement in community-dwelling adults described it as “an approach to improve home-care services for older people needing care or experiencing functional decline. It is a goal-directed and intensive intervention, which takes place in the person’s home and local surroundings with a focus on enhancing performance of everyday activities defined as important by the person” [46]. A subsequent Danish article referred to the Nordic concept of ‘help to self-help’, which is based on “ways of providing help that involves the activation of older people, the aim being to enable them to manage as much as possible themselves” [47].

The boom of reablement services (2015–2019)

Our search identified 56 articles from this time period; the majority were published by researchers from Norway (N=19) and the United Kingdom (N=12), and they include both quantitative and qualitative studies conducted in these countries as well as a few collaborative studies conducted by researchers from different countries. There are no articles from Asia, South/Central America, or Russia and only one from continental Europe. If reablement-like programmes have been or are currently being offered in these regions, they are most likely called another name. We have summarised the regional studies and organised these results alphabetically by region in Table 1.

Quantitative analysis

We created a term map based on text mining the abstracts of the final eligible articles; see Fig. 2. Our term map shows the most relevant terms from the abstracts of all 86 final eligible articles. Out of 2238 terms, 220 met the threshold of five occurrences. Here, we visualised 60% of the most relevant terms, which amounted to 132 terms with 3315 links between the terms. Each circle represents a term from the various abstracts, and the lines connecting the circles represent the interrelatedness of different terms. The size of the circle represents the number of occurrences of the term. The closer the circles are to each other indicates a high co-occurrence of terms representing a topic. The term map is coloured according to publication year, with dark blue/purple circles indicating terms from the earliest publication in 1947 until 2012 transitioning to teal in year 2013–2014, then turquoise/green in 2015–2017, and thereafter yellow indicating terms from the most recent publications in year 2018–2019.

Term Map Visualisation from Abstracts of All 86 Final Eligible Abstracts. We created a term map showing the most relevant terms from the abstracts of all 86 final eligible articles. Out of 2238 terms, 220 met the threshold of five occurrences. Here, we visualised 60% of the most relevant terms, which amounted to 132 terms with 3315 links between the terms. Each circle represents a term from the various abstracts, and the lines connecting the circles represent the interrelatedness of different terms. The size of the circle represents the number of occurrences of the term. The closer the circles are to each other indicates a high co-occurrence of terms representing a topic. The term map is coloured according to publication year, with dark blue/purple circles indicating terms from the earliest publication in 1947 until 2012 transitioning to teal in year 2013–2014, then turquoise/green in 2015–2017, and thereafter yellow indicating terms from the most recent publications in year 2018–2019

Based on the number of occurrences of terms emerging in Fig. 2, we can see the central concepts that have been emphasised in the literature throughout the years as listed in Table 2. In the earlier papers from 1947 until 2012, the core principles of reablement had already been conceptualised as a form of rehabilitation for hospitalised patients with disabilities and/or a need for home-care and social care services. In 2013–2014, there appears to be a shift of the target group from ‘patients’ to ‘users’. There was also an emphasis on developing specialised staff training that could create an impact by improving cost-effectiveness, and these programmes were offered as an alternative treatment to usual care. In 2015–2017, there appears to be another shift from ‘users’ to ‘participants’, with special attention to their goals and satisfaction with the programmes. This period also underlined the importance of assessing the performance of reablement services, particularly regarding the health professionals’ and carers’ roles, skills, knowledge, and experience (specifically, nurses and occupational therapists). In the most recent publications from 2018 to 2019, the focus shifted towards how to organise reablement teams and the programme’s overall approach, particularly on improving user involvement and collaboration between healthcare professionals, home-care personnel, and family members. The literature also highlighted an increased interest in making reablement programmes more inclusive to accommodate participants with dementia.

Discussion

We conducted an exploratory qualitative literature review and quantitative analysis to examine how the concept of ‘reablement’ has been defined and operationalised through time and space. Our scoping review shows that, in the earliest articles dating back to 1947, reablement was understood as a very specific and specialised form of rehabilitation that emphasised ‘resettling’ or ‘restoring’ a person in their local community; i.e., a social model rather than a medical model of recovery. In the earliest versions of reablement, the aim was to help disabled patients restore their functional activities and ‘resettle’ at work and home. As more formalised reablement programmes developed, particularly after 1994, they began to focus on improving independence in basic activities of daily living (ADLs) and the environmental ‘restoration’ of specifically older people. This seems to have led to the development of the ‘restorative-care model’ in the United States during the early 2000s, which incorporated principles adapted from geriatric medicine, nursing, rehabilitation, and goal attainment. At the same time, a ‘reablement’ intervention was being operationalised in the United Kingdom. Both the US and UK approaches were conceptually similar with a focus on supporting older people’s specific goals and needs; moreover, with an emphasis on involving older people themselves in the process of goal-setting, both programmes were meant to be different from traditional (conventional) forms of physical rehabilitation.

By 2011, many Western countries started to implement reablement as an alternative to traditional home-care services for older people. These programmes highlighted the burgeoning ‘reablement philosophy’: “restoring independent functioning rather than resolving health care issues, and helping people to do things for themselves rather than the traditional home care approach of doing things for people that they cannot do for themselves” [33]. Several countries continued to use terms such as ‘reablement’ and ‘restorative home care services’ interchangeably, but the intention of these programmes was generally the same: to assist older people in improving their ability to function in and around the home, and to reduce their need for ongoing home-care services.

As more programmes were implemented worldwide, reablement was typically described as a “time-intensive, time-limited intervention provided in people’s homes or in community settings, often multi-disciplinary in nature, focusing on supporting people to regain skills around daily activities” [62, 95, 96]. In contrast to the pioneering restorative-care model from 2002, such a definition is less focused on goal attainment or social engagement, and more similar to standard definitions of physical rehabilitation. Furthermore, while the overall target population has increasingly become older people, it is most often those “with diverse mortality and morbidity risks, multimorbidity, prognostic outcomes, symptoms, and disability” [89] – a set of circumstances that has long presented significant challenges to healthcare professionals working with more traditional forms of rehabilitation.

Much of the literature in our review states that, since formalised, community-based reablement services for older people first began to be widely implemented in the early 2000s, these programmes lack clear evidence of efficacy, there are inconsistencies in how the programmes are designed and offered in practice, and there is fundamentally a lack of research-based knowledge. This lack of shared understanding and consensus about what reablement is or should be is reflected in the multitude of terms used to describe nearly identical programmes in different geographical regions. Even in English-speaking countries with similar service models, programmes with similar components have different names: e.g., reablement or re-ablement (United Kingdom) and the active service model or restorative home support (Australia, New Zealand, and USA). In Scandinavia, the Swedish version is called hemrehabilitering (home rehabilitation), while the term hverdagsrehabilitering (everyday rehabilitation) is used in both Norway and Denmark, and the terms reactivation, geriatric rehabilitation, or restorative intervention are sometimes (inconsistently) used in other countries.

Moreover, some countries have recently begun to merge the terms reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation, and restorative intervention into the overarching concept of “4R interventions” to define healthcare services for older adults who need support to continue to live at home [63, 84]. By bundling these programmes together under an umbrella term, the implication is that each of these interventions has common features and goals that are relevant to a specific target group; however, the lack of an agreed set of specific “clinical and demographic characteristics makes the target population highly heterogeneous and difficult to define” [84, 89].

Our scoping review of the literature across time and space suggests that, despite definitions, aims, and theoretical aspirations to offer person-centred and goal-directed reablement, very few countries have been able to implement programmes that adequately support an older person’s social involvement or participation in their local community in a safe, culturally sensitive and adaptable way. Frequently, this is due to a lack of infrastructure, professional guidelines, training, and/or resources. Many articles also suggested that, despite already being implemented by national governments, there is a lack of capacity, training, and coordination/cohesion between professional groups to properly implement reablement programmes; in particular, professional training, coordination, and compliance remain problematic. However, even when programmes are implemented, the emphasis is often on improving older people’s physical ability/function and activities of daily living (ADLs) within the home to reduce the costs related to providing homecare and other eldercare services. With a lack of emphasis on individualised goal-setting and supporting social engagement, the reablement philosophy that aims to help older people ‘do things for themselves’ rather than ‘having things done for them’ has simply become a home-based form of physical rehabilitation. As such, the foundational intention to involve older people in setting their own self-identified outcomes and goals continues to be more of a theory than a practice.

Limitations

Due to the exploratory nature of our study and our main interest in reablement, the search term for all databases was “reablement OR re-ablement”, which resulted in papers published in English by researchers primarily working in Western countries. While this is clearly a limitation, it would also be difficult to interpret the term-map visualisations if there had been a mix of several languages; this could have resulted in multiple words in different languages with the same meaning. Moreover, this means that many countries are not represented in our search because researchers may have published articles in their native language, or they may use different terminology and/or may not describe ‘reablement’ as the concept is generally understood; i.e., the most common (and specific) features are that participants are age 65+, programmes are of a short duration (typically 6–12 sessions) and are provided by paid health professionals, such as physical/occupational therapists or homecare workers, in the participant’s home. A more precise study of how the etymology of different words relates to their specific geographical and/or cultural contexts would be extremely interesting; however, it is beyond the scope of this review. Rather, we have attempted to describe a particular genealogical development and historical trajectory that can be seen in the literature identified in our search.

A limitation of the qualitative analysis was its interpretive approach to reviewing the literature. While we attempted to analyse the texts systematically and objectively with a focus on how ‘reablement’ has been/is being described in specific time periods and geographic regions, it is possible that our analysis reflects certain personal and professional biases. However, we believe that this risk of bias in the qualitative review was mitigated by its overall coherence with the quantitative analysis and term visualisations. Furthermore, our intent with this scoping review was to trace the development of ‘reablement’ as a concept; thus, a more in-depth analysis and discussion about cultural needs for collective enablement or other societal constructions more broadly understood is certainly warranted but beyond the parameters of this review.

Conclusions

With an emphasis on the older individual’s continuing ability to participate in, contribute to and be productive and valued in society, reablement programmes for older people could be an opportunity for governments to promote a more inclusive and balanced discourse about ‘healthy ageing’. However, with a practice that focuses on restoration and recovery, old age is often treated as a disability. Our review suggests that, rather than attempting to carefully and methodically implement the first contemporary restorative-care model from 2002 (which was based on principles adapted from geriatric medicine, nursing, rehabilitation, and goal attainment), reablement programmes have been rapidly implemented since the mid-2000s to reduce costs in the eldercare sector without clear evidence for the full scope of their potential effects and outcomes; our review indicates that the long-term efficacy of reablement initiatives still remains weak and inconsistent. Furthermore, in most Western countries, reablement programmes for older people have become interchangeable with standard forms of physical rehabilitation.

As a concept, reablement should be a person-centred approach to home care that recognises the heterogeneity of older people and supports them in their self-defined goals to be both more physically independent at home and socially involved in their communities. But until legislators, health professionals, and older people can collectively reach consensus about how person-centred and goal-focused reablement can be more effectively implemented and supported in professional practice, it will be difficult to determine a conceptual description of reablement as a service that is unique, separate, and distinct from more conventional forms of physical rehabilitation. If reablement continues to lack personalisation and fail to recognise older people’s self-defined goals, then these programmes will continue to be less effective and beneficial than they could be. Thus, our review leads us to question the sustainability of reablement programmes in their current iteration – particularly with regards to the ongoing and increasing public-health challenge posed by ageing populations in many Western countries.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADLs:

-

Activities of daily living

- COPM:

-

Canadian Occupational Performance Measure

- CSED:

-

Care Services Efficiency Delivery

- IADL:

-

Instrumental ADL

- IFA:

-

International Federation on Ageing

- JAMA:

-

Journal of the American Medical Association

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- PTs:

-

Physiotherapists

- PAC:

-

Post-acute care

- RCT:

-

Randomised controlled trial

- 4R interventions:

-

Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation, and restorative interventions

References

Clotworthy A. Empowering the elderly?: A qualitative study of municipal home-health visits and everyday rehabilitation. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.forskningsdatabasen.dk/da/catalog/2392843045..

Alftberg Å, Current SL-CUJ of, 2012 U. ‘Successful ageing’in practice: Reflections on health, activity and normality in old age in Sweden. 2012 cultureunbound.ep.liu.se. [cited 2019 Jun 19]; Available from: http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se/v4/a25/cu12v4a25.pdf..

Elmelund R 2012. ‘Behandl dog folk uafhængigt af kronologisk alder’ | Information. Information [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2019 Jun 19]; Available from: https://www.information.dk/debat/2012/02/behandl-folk-uafhaengigt-kronologisk-alder..

Lassen A. Studies TM-J of A, Undefined. Unmaking old age: Political and cognitive formats of active ageing. J Aging Stud. 2014; [cited 2019 Jun 19]; Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890406514000267..

Laliberte Rudman D. Embodying positive aging and neoliberal rationality: Talking about the aging body within narratives of retirement. J Aging Stud. 2015;34:10–20 Aug [cited 2019 Jun 19];. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S089040651500033X..

Mishra V, Barratt J. Reablement and Older People. 2016 [cited 2019 Jun 19]. Available from: http://www.ifa-copenhagen-summit.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Copenhagen-Summit-Final-Report.pdf..

Cations M, Laver KE, Crotty M, Cameron ID. Rehabilitation in dementia care. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):171–4 Available from: http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/..

Meyer T, Gutenbrunner C, et al. JB-J of, 2011 U. Towards a conceptual description of rehabilitation as a health strategy. J Rehabil Med. 2011; [cited 2019 Jun 19]; Available from: https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/mjl/sreh/2011/00000043/00000009/art00003..

VOSviewer - Visualizing scientific landscapes [Internet]. [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: http://www.vosviewer.com/..

Kottke F, Knapp M. The development of physiatry before 1950. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988; [cited 2019 Jun 19]; Available from: https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/3056328..

Brandt E, Pope A. Enabling America: Assessing the role of rehabilitation science and engineering. In: Committee on Assessing Rehabilitation Science and Engineering, Institute of Medicine; National Academies Press; 1997. [cited 2019 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=n0efAwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT16&dq=Brandt,+Jr.,+E.+N.+and+Pope,+A.+M.+(eds.)+1997.+Enabling+America:+Assessing+the+Role+of+Rehabilitation+Science+and+Engineering.+Committee+on+Assessing+Rehabilitation+Science+and+Engi..

Nixon JA. Disablement and reablement. Physiotherapy. 1947;32(11):172–4 Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20251159..

Collis E. Reablement of children with infantile cerebral palsy. Lancet. 1947;2(6468):239–43..

Grenville-Mathers R. Reablement of tuberculous patients. Lancet. 1949;1(6553):563–5..

Grant WR. Principles of rehabilitation. XIV The reablement of the heavily handicapped patient. Practitioner. 1962;188:281–2..

Nichols PJR. Rehabilitation in the reorganised National Health Service. Rehabilitation. 1975;94:11–8 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed2&NEWS=N&AN=6148785..

Leplaideur J, Cabanal J, Azorin M. Treatment of rheumatic disablement by functional reablement in specialized centres. Readaptation. 1977;236:28–32 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed2&NEWS=N&AN=8030979..

Dupontreve M. Ergotherapy in reablement of the hand in rheumatoid arthritis. Readaptation. 1977;236:33–9 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed2&NEWS=N&AN=8030980..

Cooper. Occupational reablement of handicapped persons with technical aids. Readaptation. 1977;238:11–7 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed2&NEWS=N&AN=8069382..

Newton. Integration of supporting services. Ulster Med J. 1978;47(SUPP. 1):49–53 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed2&NEWS=N&AN=8341440..

Ebrahim S. The goals of rehabilitation for older people. Rev Clin Gerontol. 1994;4(2):93–5 Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=1995-11075-001&site=ehost-live..

Tinetti ME, Baker D, Gallo WT, Nanda A, Charpentier P, O’Leary J. Evaluation of restorative care vs usual care for older adults receiving an acute episode of home care. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2098–105 Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/194857..

Baker D, Gottschalk M, Eng C, et al. SW-T, 2001 U. The design and implementation of a restorative care model for home care. Gerontologist. 2001; [cited 2019 Jun 17]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article-abstract/41/2/257/648315..

Nancarrow SA, Shuttleworth P, Tongue A, Brown L. Support workers in intermediate care. Heal Soc Care Community. 2005;13(4):338–44 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed9&NEWS=N&AN=40978141..

Newbronner E, Baxter M, Chamberlain R, Maddison J, Arksey H, Glendinning C. Research into the Longer Term Effects/Impacts of Re-ablement Services Department of Health/CSED. 2007 [cited 2019 Jun 19]. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/pubs/pdf/reab.pdf..

Petch A. Reablement and the Role of the Occupational Therapist. J Integr Care. 2008;16(2):38–9[cited 2019 Jul 22]. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1108/14769018200800016..

Glendinning C, Clarke S, Hare P, Maddison J, Newbronner L. Progress and problems in developing outcomes-focused social care services for older people in England. Heal Soc Care Community. 2008;16(1):54–63 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed10&NEWS=N&AN=351009770..

Glendinning C, Newbronner E. The effectiveness of home care Reablement – developing the evidence base. J Integr Care. 2008;16(4):32–40. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1108/14769018200800031..

Glendinning C, Jones K, Baxter K, Rabiee P, Curtis LA, Wilde A, et al. Home Care Reablement Services: Investigating the longer-term impacts; 2010. p. 1–254. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/Reablement.pdf..

Samuel M. What is reablement? Community care. 2010; Available from: https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2010/09/20/what-is-reablement/..

While A. Re-ablement for home care. Br J Community Nurs. 2011;16(2):102 Available from: http://www.internurse.com/cgi-bin/go.pl/library/article.cgi?uid=81762..

Wallin M, Talvitie U, Cattan M. Interaction between clients and physiotherapists in group exercise classes in geriatric rehabilitation. Adv Physiother. 2009;11(3):145–53 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed11&NEWS=N&AN=355791147..

Francis J, Fisher M, Rutter D. Reablement: a cost-effective route to better outcomes. 2011 [cited 2019 Jul 22]. Available from: https://www.scie.org.uk/publications/briefings/files/briefing36.pdf..

Rabiee P, Glendinning C. Organisation and delivery of home care re-ablement: what makes a difference? Heal Soc Care Community. 2011;19(5):495–503 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed12&NEWS=N&AN=51469560..

Lee W-J, Peng L-N, Cheng Y-Y, Liu C-Y, Chen L-K, Yu H-C. Effectiveness of short-term interdisciplinary intervention on postacute patients in Taiwan. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(1):29–32 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed12&NEWS=N&AN=360232514..

Wilde A, Glendinning C, A. W, Wilde A, Glendinning C. “If they’re helping me then how can I be independent?” The perceptions and experience of users of home-care re-ablement services. Heal Soc Care Community. 2012;20(6):583–90 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed13&NEWS=N&AN=52116100..

Ryburn B, Wells Y, Foreman P. Enabling independence: restorative approaches to home care provision for frail older adults. Health Soc Care Community. 2009;17(3):225–34. May [cited 2019 Jun 17]Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00809.x..

Newton C. Personalising reablement: inserting the missing link. Work Older People. 2012;16(3):117–21 [cited 2019 Jul 22];. Available from: http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/10.1108/13663661211260934..

Burton E, Lewin G, Clemson L, Boldy D. Effectiveness of a lifestyle exercise program for older people receiving a restorative home care service: A pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1591–601 Available from: http://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=18320..

Lewin GF, Alfonso HS, Alan JJ. Evidence for the long term cost effectiveness of home care reablement programs. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:1273–81 Available from: http://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=17678..

Cochrane A, McGilloway S, Furlong M, Molloy D, Stevenson M. Home-care “re-ablement” services for maintaining and improving older adults’ functional independence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(11):CD010825 Available from: http://as.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Brand/id-6.html..

Whitehead PJ, AEE D, Walker MF, Parry RH. Interventions to reduce dependency in personal activities of daily living in community-dwelling adults who use homecare services: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2013;2:49 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed14&NEWS=N&AN=370121813..

Lewin G, Allan J, Patterson C, Knuiman M, Boldy D, Hendrie D. A comparison of the home-care and healthcare service use and costs of older Australians randomised to receive a restorative or a conventional home-care service. Health Soc Care Community. 2014;22(3):328–36 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed15&NEWS=N&AN=609185120..

Whitehead PJ, AER D, Walker MF, Parry RH, ID MG, Latif Z. Occupational Therapy in HomEcare Re-ablement Services (OTHERS): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15(1):447 Available from: http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/15/1/447..

Boniface G, Mason M, Macintyre J, Synan C, Riley J. The effectiveness of local authority social services’ occupational therapy for older people in Great Britain: a critical literature review. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76(12):538–47 Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2014-01632-002&site=ehost-live..

Tuntland H, Espehaug B, Forland B, Hole A, Kjerstad E. Reablement in community-dwelling adults: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:–139 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed15&NEWS=N&AN=615126990..

Dahl HM, Eskelinen L, Hansen EB. Coexisting principles and logics of elder care: help to self-help and consumer-oriented service? Int J Soc Welf. 2015;24(3):287–95 Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2015-27418-009&site=ehost-live..

Clare L, Kudlicka A, Oyebode JR, Jones RW, Bayer A, Leroi I, et al. Goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation for early-stage Alzheimer’s and related dementias: the GREAT RCT, vol. 23. England: Health technology assessment (Winchester, England); 2019. p. 1–242..

Clare L, Kudlicka A, Oyebode JR, Jones RW, Bayer A, Leroi I, et al. Individual goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation to improve everyday functioning for people with early-stage dementia: A multicentre randomised controlled trial (the GREAT trial). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(5):709–21 Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1166..

Poulos CJ, Bayer A, Beaupre L, Clare L, Poulos RG, Wang RH, et al. A comprehensive approach to reablement in dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2017;3(3):450–8 [cited 2019 Feb 7];. Available from: http://www.journals.elsevier.com/alzheimers-and-dementia-translational-research-and-clinical-interventions/..

Jeon Y-H, Clemson L, Naismith SL, Mowszowski L, McDonagh N, Mackenzie M, et al. Improving the social health of community-dwelling older people living with dementia through a reablement program. Int Psychogeriatr. 2018;30(6):915–20 [cited 2019 Feb 7];Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1041610217001533/type/journal_article..

Poulos RG, Gresham M, O’Connor CM, Poulos CJ. Bridging the gap: From reablement policy to practice for people with dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2018;4:508–9 [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2352873718300519..

Jeon Y. Optimising social health of people living with dementia and family caregivers through person centered and reablement approaches to care. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27(SUPPL. 1):S28 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed16&NEWS=N&AN=72187853..

Jeon Y-H, Kendig H. Care and support for older people. In: O’Loughlin K, Browning C, Kendig H, editors. Ageing in Australia: Challenges and opportunities. 88 Mallett Street, Camperdown, NSW, Australia: Jeon, Yun-Hee, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Sydney; 2050. Springer Science + Business Media; 2017. p. 239–59. (International perspectives on aging; Vol 16; ISSN: 2197–5841 (Print), 2197-585X (Electronic); vol. 16). Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2016-62137-012&site=ehost-live..

Lewin G, Concanen K, Youens D. The home independence program with non-health professionals as care managers: an evaluation. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:807–17 Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=30969..

Lawn S, Westwood T, Jordans S, O’Connor J. Support workers as agents for health behavior change: an Australian study of the perceptions of clients with complex needs, support workers, and care coordinators. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2017;38(4):496–516 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexa&NEWS=N&AN=622370625..

Lawn S, Westwood T, Jordans S, Zabeen S, O’Connor J. Support workers can develop the skills to work with complexity in community aged care: an Australian study of training provided across aged care community services. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. 2017;38(4):453–70 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexa&NEWS=N&AN=622371880..

Low L-F, Venkatesh S, Clemson L, Merom D, Casey A-N, Brodaty H. Feasibility of LifeFul, a relationship and reablement-focused culture change program in residential aged care. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):–129 [cited 2019 Feb 7];Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=625963398..

Doh D, Smith R, Gevers P. Reviewing the reablement approach to caring for older people. Ageing Soc. 2019:1–13 Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ageing-and-society/article/reviewing-the-reablement-approach-to-caring-for-older-people/2985F4C27B9CC7AAB849232635CE05B9..

Jacobs SP, Parsons M, Rouse P, Parsons J, Gunderson-Reid M. Using benchmarking to assist the improvement of service quality in home support services for older people-IN TOUCH (Integrated Networks Towards Optimising Understanding of Community Health). Eval Program Plann. 2018;67:113–21 [cited 2019 Feb 7];. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=626264443..

Metzelthin SF, Rooijackers TH, Zijlstra GAR, van Rossum E, Veenstra MY, Koster A, et al. Effects, costs and feasibility of the “Stay Active at Home” Reablement training programme for home care professionals: study protocol of a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):–276 [cited 2019 Feb 7]Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=624962395..

Tessier A, Beaulieu M-D, Mcginn CA, Latulippe R. Effectiveness of reablement: a systematic review. Healthc Policy. 2016;11(4):49–59 Available from: http://www.longwoods.com/content/24594..

Sims-Gould J, Tong CE, Wallis-Mayer L, Ashe MC. Reablement, reactivation, rehabilitation and restorative interventions with older adults in receipt of home care: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(8):653–63 Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1525861016306740..

Winkel A, Langberg H, Waehrens EE. Reablement in a community setting. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;37(15):1347–52. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.963707..

Pettersson C, Iwarsson S. Evidence-based interventions involving occupational therapists are needed in re-ablement for older community-living people: A systematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2017;80(5):273–85[cited 2019 Jul 9]. Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022617691537..

Gustafsson L-K, Östlund G, Zander V, Elfström ML, Anbäcken E-M. ‘Best fit’ caring skills of an interprofessional team in short-term goal-directed reablement: older adults’ perceptions. Scand J Caring Sci. 2019 17 [cited 2019 Feb 7]; Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12650..

Tuntland H, Aaslund MK, Espehaug B, Forland O, Kjeken I. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:145 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed16&NEWS=N&AN=615192571..

Langeland E, Tuntland H, Forland O, Aas E, Folkestad B, Jacobsen FF, et al. Study protocol for a multicenter investigation of reablement in Norway. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:111 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed16&NEWS=N&AN=615164977..

Tuntland H, Aaslund M, Langeland E, Espehaug B. Psychometric properties of the Canadian occupational performance measure in home-dwelling older adults. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:411–23 Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=32225..

Kjerstad E, Tuntland HK. Reablement in community-dwelling older adults: a cost-effectiveness analysis alongside a randomized controlled trial. Heal Econ Rev. 2015;6(1):–15 Available from: http://www.springerlink.com/content/2191-1991/..

Tuntland H, Kjeken I, Langeland E, Folkestad B, Espehaug B, Forland O, et al. Predictors of outcomes following reablement in community-dwelling older adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:55–63..

Langeland E, Tuntland H, Folkestad B, Førland O, Jacobsen FF, Kjeken I. A multicenter investigation of reablement in Norway: a clinical controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):–29 [cited 2019 Feb 7]Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=626198275..

Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Forland O, Alvsvag H. The reablement team’s voice: A qualitative study of how an integrated multidisciplinary team experiences participation in reablement. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:575–85 Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=33365..

Hjelle KM, Tuntland H, Forland O, Alvsvag H. Driving forces for home-based reablement; a qualitative study of older adults’ experiences. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25(5):1581–9 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=625204779..

Birkeland A, Tuntland H, Forland O, Jakobsen FF, Langeland E. Interdisciplinary collaboration in reablement - a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:195–203..

Hjelle KM, Alvsvag H, Forland O. The relatives’ voice: how do relatives experience participation in reablement? A qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2017;10:1–11 Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/getfile.php?fileID=34255..

Hjelle KM, Skutle O, Alvsvåg H, Førland O. Reablement teams’ roles: a qualitative study of interdisciplinary teams’ experiences. J Multidiscip Healthc . 2018;11:305–316[cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/reablement-teams-roles-a-qualitative-study-of-interdisciplinary-teams%2D%2Dpeer-reviewed-article-JMDH..

Moe A, Ingstad K, Brataas HV. Patient influence in home-based reablement for older persons: qualitative research. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):–736 [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexa&NEWS=N&AN=622886533..

Jakobsen FA, Vik K. Health professionals’ perspectives of next of kin in the context of reablement. Disabil Rehabil. 2018:1–8 [cited 2019 Feb 7];. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09638288.2018.1450452..

Moe C, Brinchmann BS. Tailoring reablement: a grounded theory study of establishing reablement in a community setting in Norway. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;26(1):113–21 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emexb&NEWS=N&AN=623980099..

Jokstad K, Skovdahl K, Landmark BT, Haukelien H. Ideal and reality; Community healthcare professionals’ experiences of user-involvement in reablement. Health Soc Care Community. 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 7]; Available from:. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12708..

Bonsaksen T, Dolva A-S, Hagby C, Sveen U, Horghagen S, Thyness EM, et al. Involvement in Research and Development Projects Among Community-working Occupational Therapists in Norway. Occup Ther Heal Care. 2018:1–15 [cited 2019 Feb 7]. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/07380577.2018.1526434..

Eliassen M, Henriksen NO, Moe S. Physiotherapy supervision of home trainers in interprofessional reablement teams. J Interprof Care. 2018:1–7 [cited 2019 Feb 7]Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13561820.2018.1541877..

Eliassen M, Henriksen NO, Moe S. Variations in physiotherapy practices across reablement settings. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018:1–14 Available from: Variations in physiotherapy practices across reablement settings..

Eliassen M, Henriksen N, Moe S. The practice of support personnel, supervised by physiotherapists, in Norwegian reablement services. Physiother Res Int. 2019;24(1):e1754. [cited 2019 Feb 7]Available from. https://doi.org/10.1002/pri.1754..

Teale EA, Young JB. A patient reported experience measure (PREM) for use by older people in community services. Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):667–72 Available from: http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/..

Whitehead PJ, Worthington EJ, Parry RH, Walker MF, Drummond AER. Interventions to reduce dependency in personal activities of daily living in community dwelling adults who use homecare services: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(11):1064–76..

Bond RR, Mulvenna MD, Finlay DD, Martin S. Multi-faceted informatics system for digitising and streamlining the reablement care model. J Biomed Inform. 2015;56:30–41 Available from: http://www.elsevier.com/inca/publications/store/6/2/2/8/5/7/index.htt..

Legg L, Gladman J, Drummond A, Davidson A. A systematic review of the evidence on home care reablement services. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(8):741–9 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed17&NEWS=N&AN=616562801..

Whitehead P, Walker M, Parry R, Latif Z, McGeorge I, Drummond A. Occupational Therapy in HomEcare Re-ablement Services (OTHERS): results of a feasibility randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e011868 Available from: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed17&NEWS=N&AN=619793511..

Mann R, Beresford B, Parker G, Rabiee P, Weatherly H, Faria R, et al. Models of reablement evaluation (MoRE): a study protocol of a quasi-experimental mixed methods evaluation of reablement services in England. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(a):375..

Tew J, Nicholls V, Plumridge G, Clarke H. Family-inclusive approaches to reablement in mental health: models, mechanisms and outcomes. Br J Soc Work. 2017;47(3):864–84 Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2017-30604-011&site=ehost-live..

Mayhew E, Beresford B, Laver-Fawcett A, Aspinal F, Mann R, Bechtold K, et al. The Hopkins Rehabilitation Engagement Rating Scale - Reablement Version (HRERS-RV): Development and psychometric properties. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27(3):777–87 [cited 2019 Feb 7]Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/hsc.12696..

Bauer A, Fernandez J, Henderson C, Wittenberg R, Knapp M. Cost-minimisation analysis of home care reablement for older people in england: A modelling study. Health Soc Care Community. 2019; Apr 21; Available from: https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=psyh&AN=2019-22481-001&site=ehost-live..

Cochrane A, Furlong M, McGilloway S, Molloy DW, Stevenson M, Donnelly M. Time-limited home-care reablement services for maintaining and improving the functional independence of older adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016, 2016;(10):CD010825 Available from: http://as.wiley.com/WileyCDA/Brand/id-6.html..

Aspinal F, Glasby J, Rostgaard T, Tuntland H, Westendorp RGJ. New horizons: Reablement - supporting older people towards independence. Age Ageing. 2016;45(5):574–8 Available from: http://ageing.oxfordjournals.org/..

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The authors are supported by Nordea Fonden [02–2017-1749] and Novo Nordisk Fonden Challenge Programme: Harnessing the Power of Big Data to Address the Societal Challenge of Aging [NNF17OC0027812]. These funding bodies had no influence on the design of the study or the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, nor were they involved in writing the manuscript. The authors are affiliated with the international research network ReAble: https://reable.auckland.ac.nz/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AC and SK jointly examined all articles for inclusion in the review; AC conducted the qualitative review and wrote the manuscript while SK performed the quantitative analysis and constructed the term maps. Disagreements were resolved through consultation with the third author (RGJW), who also provided comments/revisions to the manuscript. All authors have read and approved of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Clotworthy, A., Kusumastuti, S. & Westendorp, R.G.J. Reablement through time and space: a scoping review of how the concept of ‘reablement’ for older people has been defined and operationalised. BMC Geriatr 21, 61 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01958-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01958-1