Abstract

Background

Non-specific symptoms, such as confusion, are often suspected to be caused by urinary tract infection (UTI) and continues to be the most common reason for suspecting a UTI despite many other potential causes. This leads to significant overdiagnosis of UTI, inappropriate antibiotic use and potential harmful outcomes. This problem is particularly prevalent in nursing home settings.

Methods

A systematic review of the literature was conducted assessing the association between confusion and UTI in the elderly. PubMed, Scopus and PsychInfo were searched with the following terms: confusion, delirium, altered mental status, acute confusional state, urinary tract infection, urine infection, urinary infection and bacteriuria. Inclusion criteria and methods were specified in advance and documented in the protocol, which was published with PROSPERO (registration ID: CRD42015025804). Quality assessment was conducted independently by two authors. Data were extracted using a standardised extraction tool and a qualitative synthesis of evidence was made.

Results

One thousand seven hunderd two original records were identified, of which 22 were included in the final analysis. The quality of these included studies varied, with frequent poor case definitions for UTI or confusion contributing to large variation in results and limiting their validity. Eight studies defined confusion using valid criteria; however, no studies defined UTI in accordance with established criteria. As no study used an acceptable definition of confusion and UTI, an association could not be reliably established. Only one study had acceptable definitions of confusion and bacteriuria, reporting an association with the relative risk being 1.4 (95% CI 1.0–1.7, p = 0.034).

Conclusions

Current evidence appears insufficient to accurately determine if UTI and confusion are associated, with estimates varying widely. This was often attributable to poor case definitions for UTI or confusion, or inadequate control of confounding factors. Future well-designed studies, using validated criteria for UTI and confusion are required to examine the relationship between UTI and acute confusion in the elderly. The optimal solution to clarify this clinical issue would be a randomized controlled trial comparing the effect of antibiotics versus placebo in patients with new onset or worsening confusion and presence of bacteriuria while lacking specific urinary tract symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well documented that lower urinary tract infection (UTI) should only be diagnosed when there are new onset localising genitourinary signs and symptoms and a positive urine culture result [1]. However, despite new onset or worsening of confusion being a non-specific symptom, it continues to be the most common reason for suspecting a lower UTI in elderly patients, often leading to antibiotic treatment [2,3,4]. The diagnosis of UTI is further complicated by the high prevalence of asymptomatic bacteriuria, particularly in nursing home residents, varying between 25 and 50% for women and 15–40% for men, without an indwelling urinary catheter [5]. While urine cultures can guide the choice of antibiotic, their poor positive predictive value means a positive culture alone should not warrant initiation of antibiotics [6]. Additionally, evidence suggests patients with confusion and dementia are more likely to be continuously bacteriuric [7]. Due to all of these confounding factors, new onset or worsening of non-specific symptoms in residents is one of the major diagnostic challenges in caring for the elderly.

Subsequently, many different consensus based criteria to enable appropriate diagnosis of UTI have been devised, most notably the revised Mcgeer and updated Loeb criteria [1, 8]. Despite the difficulty of diagnosing UTI, there is sound evidence that elderly residents with symptomatic lower UTI should receive antibiotic treatment and elderly residents with asymptomatic bacteriuria should not [9, 10]. Although inappropriate antibiotic use results in those few residents suffering from a lower UTI to be treated promptly, it leads to significant overdiagnosis of UTI and potentially harmful outcomes through misdiagnosis. With many residents receiving unnecessary antibiotics with possible adverse reactions, and the ever-increasing rates of antibiotic resistance, it is evident that inappropriate antibiotic use in this population must be reduced [11].

A previous literature review conducted by Balogun et al. exclusively reviewed the association between symptomatic UTI and delirium in the elderly in five publications. It concluded that there may be an association between symptomatic UTI and delirium; however, some methodological flaws may have led to biased results [12]. It was limited by only using the term delirium and excluding terms like confusion, resulting in many publications potentially being excluded. In addition, Balogun et al. only searched the Medline database potentially missing important publications.

UTI is a broad diagnosis encompassing infections arising from all levels of the urinary tract, ranging in severity from acute cystitis to acute pyelonephritis. This systematic review aims to review the evidence for the association between acute cystitis or bacteriuria and confusion in the elderly in all care settings.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [13]. Inclusion criteria and methods were specified in advance and documented in the review protocol. The initial protocol was published with PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews, registration number CRD42015025804.

Eligibility criteria

This review included quantitative studies which met the following inclusion criteria:

-

Elderly participants. The majority of the participants in the study must be representative of an elderly population, defined as the median or mean age ≥ 65 years.

-

Primary studies in which participants with lower UTI or bacteriuria were assessed for concurrent confusion, or participants with confusion were assessed for concurrent UTI or bacteriuria.

-

Any care setting (Hospital, Community, Long Term Care Facility).

The following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

Studies that refer to specific sub-populations of patients with UTI. Examples include: stroke patients, Alzheimers or dementia patients or post-surgical patients

-

Studies that exclusively report catheter associated UTI;

-

Non-English publications

-

Case studies

The primary outcomes of interest were confusion, UTI and bacteriuria. Due to the large variety of terminology that surrounds the symptom of confusion, definitions used for confusion in this review encompassed: confusion, acute confusional state, delirium, altered mental status, altered mental state. This broad definition was used so as to capture all studies which may have assessed confusion but used alternative terminology. No absolute lower age limit was set, as it was anticipated that these would have an overall negligible effect on the data. This was so as to not exclude studies which may present data representative of an elderly population but which included a small minority of non-elderly participants. Studies that referred to specific subpopulations, or exclusively reported catheter associated UTI were also excluded so as to explore the association between confusion and UTI or bacteriuria in a general elderly population.

Identification of studies

Three databases were accessed to identify studies eligible for this review: PubMed, Scopus and PsycINFO (via ProQuest). The search terms were related to three key topics: confusion, UTI and bacteriuria (Table 1) with adaptations for Scopus and PsycINFO. No restrictions on date or language were applied and studies published up to August 2015 were included. Once the final list of full text articles was determined, the references and citation history of the included studies were screened for other potential studies eligible for the review. The full texts of any new studies deemed possibly eligible for inclusion, were then retrieved and assessed.

Study selection

After each database had been searched, the search results were collated and duplicates removed. Titles and, where available, abstracts retrieved were assessed for eligibility against the described inclusion criteria. Studies that clearly did not meet the review’s criteria were excluded. The full texts of potentially eligible studies and those that after title and abstract screening were not able to be definitively excluded were retrieved. The full text articles were then assessed for eligibility by the first reviewer (SM). Studies that could not be definitively excluded were discussed and resolved by consensus with another reviewer (RG). Studies excluded at this stage were recorded and their reason for exclusion is reported.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed by one author (SM) using a standardised, pre-designed data extraction form, with the exception of data relevant to the quality assessment which was extracted by two review authors (SM and AB) independently. Any discrepancies identified were resolved by consensus, or through discussion with the third reviewer (RG). Data extracted from each eligible study included:

-

General information: author, year of publication, title, type of publication, journal;

-

Study characteristics: aim, study design;

-

Patient sample: number, age, gender, presence of urinary catheters;

-

Care setting: Hospital, Long-term Care Facility, Community;

-

Confusion criteria: criteria utilised to diagnose confusion;

-

UTI/Bacteriuria criteria: criteria utilised to diagnose UTI/bacteriuria;

-

Results: association between UTI/bacteriuria and confusion if reported, rates of patients with UTI/bacteriuria having confusion, rates of patients with confusion having UTI/bacteriuria;

-

Risk of bias: see Quality Assessment below

Quality assessment / risk of Bias

Two review authors (SM and AB) assessed the risk of bias of included studies independently, with any discrepancies being resolved by consensus, or through discussion with a third reviewer (RG), if necessary. The risk of bias was assessed using a modified version of the assessment checklist developed by Downs and Black [14]. Quality items that pertained to interventions and trial studies were removed as they were not deemed to be appropriate for the studies included in this review. An additional five quality items were added to the quality assessment to determine if studies described the criteria used for confusion, UTI and bacteriuria, and if their criteria for UTI and confusion were valid and reliable. Criteria for confusion were deemed valid and reliable if accepted criteria were utilised, including: the Confusion Assessment Method, the Organic Brain Syndrome Scale or the Diagnosis and Statistical Manual (DSM) criteria [15,16,17]. Similarly, criteria for UTI were deemed valid and reliable if established criteria for UTI were utilised, including: the McGeer Criteria, the revised McGeer Criteria, the Loeb Criteria, or the Revised Loeb Criteria [1, 8, 18, 19]. The modified checklist finally consisted of 14 quality items, grouped into: reporting, internal validity, external validity and criteria (Table 2). The risk of bias for each quality item was reported as low risk of bias, high risk of bias, unclear risk of bias or not applicable.

Data synthesis

Although the broad search strategy described was employed to enable the meta-analysis of data from included studies if deemed feasible, due to the heterogeneity of the data and the variety of definitions for confusion and UTI reported between the studies, meta-analysis was not conducted. Alternatively, a qualitative synthesis of the findings from the included studies was performed, structured around the quality of data, consistency of definitions and the evidence for the association between confusion and UTI.

Results

Study selection

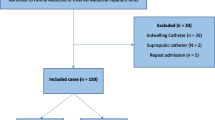

Searches identified a total of 1907 records (Fig. 1). After duplicate records were removed, 1722 remained. These articles were then screened by title and abstract against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, leading to the exclusion of 1657 articles, as it appeared they clearly did not fulfil the eligibility criteria. Eleven potential records were excluded as their full texts were unable to be obtained. The full texts of the remaining 54 articles were closely examined. Thirty-five articles were excluded at this stage, with the most common reason being the study reported confusion and UTI/bacteriuria in their population, but not in relation to each other [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Other common reasons included: the study did not report confusion [35,36,37,38,39], the study did not report UTI/bacteriuria [2, 40,41,42,43], the study only reported the association in a specific subpopulation [44,45,46], or the study combined their measurement of confusion with other parameters [7, 47,48,49,50]. Two studies were also excluded as UTI and confusion were not assessed concurrently [51] and reported UTI was combined with other parameters [52]. Three additional studies that met the inclusion criteria were identified by searching the references of relevant articles and searching for studies that cited these articles. No studies were deemed suitable for quantitative synthesis. A total of 22 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review.

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies included in this review varied considerably (Fig. 2). This is partially due to inclusion of all studies that reported data on the rate of confusion in patients with suspected UTI or bacteriuria, or vice versa, even if it was not the main objective of the study. Reporting of main outcomes, description of patient characteristics and number of non-responders/patients lost to follow up were done well in most studies, with only one small study not clearly describing their main outcomes [53] and four studies not reporting the number of non-responders or patients lost to follow up [40, 54,55,56]. In terms of internal validity, all applicable studies were deemed to have used appropriate statistical tests; however, half of the studies did not clearly describe other principle confounders in their comparison groups. The external validity, however, of all studies, was generally very high.

The quality of the criteria used to define UTI, bacteriuria and confusion varied considerably and was generally quite poor. No studies used criteria for UTI completely consistent with the revised Mcgeer or Loeb Criteria. Two studies employed a reproducible definition of UTI although neither employed published explicit criteria developed through expert consensus. [57, 58]. Many studies utilised discharge coding from patient databases which resulted in the reliability of their criteria being unable to be determined [59,60,61,62,63,64,65]. Two studies were identified that used criteria that were clearly inappropriate [66, 67]. Three studies did not provide a definition for UTI, as they reported confusion in association with validated criteria for bacteriuria only [3, 68, 69]. Only one of these studies utilised an appropriate definition of bacteriuria and validated criteria for delirium [3]. Three of the studies which provided a definition for UTI also defined criteria for bacteriuria [56, 58, 67].

Almost all studies provided a definition of confusion criteria, but only eight studies used criteria that were valid and reliable (Table 3) [3, 54, 55, 60, 66, 70,71,72]. Five studies used criteria for confusion which were clearly not valid or reliable [65, 67,68,69, 73], and nine were unclear in their criteria used (Table 4) [53, 56,57,58,59, 61,62,63,64].

Characteristics of included studies

There were four large retrospective cross-sectional studies, and among the remaining studies the number of patients in each study varied considerably from small community samples of 9 to larger hospital samples of 710 (Tables 3 and 4). The majority of the studies identified were cross-sectional in design. Approximately half of the studies had an entirely elderly population ≥ 65 years (n = 10), with the other half of studies having populations deemed to be representative of an elderly population by median or mean age ≥ 65 years (n = 10). In the two remaining studies, one conducted in a nursing home and the other in a psychogeriatric unit, the demographics of the patient sample were not provided. They were believed to be representative of an elderly population by their care setting. The proportion of participants with urinary catheters was unclear in the majority of included studies (n = 14). In the remaining studies, urinary catheter rates were high, 37–51% (n = 3), low 1.8–5.5% (n = 2) and none (n = 3). The majority of the studies were conducted in a hospital setting (n = 14), followed by nursing homes (n = 6) and community settings (n = 2). Interestingly, only two of the included studies had the explicit aim of exploring the association between confusion and UTI; however, ten studies did partially explore this association.

Results of individual studies

Among the included studies, the rate of confusion in patients with suspected UTI was most commonly reported (n = 13) followed by the rate of suspected UTI in patients with confusion (n = 10). Some studies reported the rate of confusion in patients with bacteriuria (n = 4) and one study reported the rate of bacteriuria in patients with confusion. The majority of studies reported confusion as delirium (n = 15), followed by a few reporting confusion (n = 3), altered mental state (n = 2), and mental status changes (n = 1), with one study reporting both delirium and altered mental status [57]. Twelve studies analysed the correlation between suspected UTI or bacteriuria and confusion (Tables 3 and 4).

Synthesis of results

No study used validated definitions of both confusion and UTI, so this association could not be reliably established. Only one study by Juthani-Metha et al. had an acceptable definition of confusion and an acceptable definition of bacteriuria. They found an association between bacteriuria and confusion with the relative risk being 1.4 (95% CI 1.0–1.7, p = 0.034) [3].

Discussion

Summary of the evidence

Following this review, it is evident that all of the studies which have explored the association between suspected UTI and confusion are methodologically flawed, due to poor case definition for UTI or confusion, or inadequate control of confounding factors introducing significant bias. Subsequently, no accurate conclusions about the association between UTI and confusion can be drawn. One study of acceptable quality shows an association between confusion and bacteriuria. However, this sample of patients in whom they tested bacteriuria and pyuria were patients already suspected of having a UTI, introducing a bias into their calculation [3]. In summary, none of the 22 publications had sufficient methodological quality to enable valid conclusions.

Frailty

Frail residents are more likely to have bacteriuria [74]. Frailty also predisposes for cognitive decline [75, 76]. Hence, there might be an indirect link between confusion and bacteriuria, easily misinterpreted as UTI causing confusion. This might explain some of the trends found in the existing literature.

Confusion linked to acute cystitis or pyelonephritis

Studies including hospitalised patients are likely to also include patients with pyelonephritis, a condition likely to result in confusion in a fragile elderly person. However, the typical nursing home situation usually involves the suspicion of confusion caused by a lower UTI (acute cystitis) in an afebrile patient.

The primary aim of this review was not to evaluate the association between pyelonephritis and confusion. The primary question was if lower UTI with no fever in residents without a urinary catheter, with or without localised symptoms such as acute dysuria, urgency or frequency, is associated with confusion. This review concludes that current evidence does not provide a clear answer to this question.

Strengths and limitations of the review

The strengths of this review are mainly due to its methodological quality; that it utilised a broad search strategy, with no limits to age or date applied. This allowed for studies that were representative of an elderly population and without the explicit aim of reporting the relationship between confusion and UTI to be identified. Another strength of this review was the registration of a protocol with pre-specified objectives and methods. The use of a second reviewer independently assessing the quality of selected studies also increases the quality of the review. Limitations included limiting articles to English and being unable to assess the eligibility of the unobtainable full-texts. This review also did not attempt to include studies from the unpublished literature, introducing possible publication bias.

Conclusion

Insufficient evidence is available to accurately determine if an afebrile lower UTI in elderly patients without an indwelling urinary catheter causes confusion. Although studies exist that suggest there may be an association, they are significantly limited by their methodological quality. This is largely due to the frequent use of unreliable criteria for UTI and confusion, and frequently poor controlling for confounding factors. A reasonable attempt to resolve this issue are the McGeer and Loeb criteria [1, 8, 19]. However, it should be kept in mind that in the case of confusion these criteria are expert recommendations that cannot be confirmed due to the lack of an appropriate gold standard. This review highlights the importance of conducting well-designed studies and demonstrates that further high-quality research exploring the relationship between lower urinary tract infection and acute confusion is required. A well-designed, large observational study with validated criteria for UTI and confusion may provide further insight into this association. However, the optimal solution to clarify this issue would be a randomized controlled trial comparing the effect of antibiotics versus placebo in patients with new onset or worsening confusion and presence of bacteriuria while lacking specific urinary tract symptoms.

Abbreviations

- UTI:

-

Urinary tract infection

References

Stone ND, Ashraf MS, Calder J, Crnich CJ, Crossley K, Drinka PJ, et al. Surveillance definitions of infections in long-term care facilities: revisiting the McGeer criteria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(10):965–77.

Juthani-Mehta M, Tinetti M, Perrelli E, Towle V, Van Ness PH, Quagliarello V. Interobserver variability in the assessment of clinical criteria for suspected urinary tract infection in nursing home residents. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(5):446–9.

Juthani-Mehta M, Tinetti M, Perrelli E, Towle V, Van Ness P, Quagliarello V. Clinical features to identify urinary tract infection in nursing home residents: a cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):963–70.

Nicolle LE, Strausbaugh LJ, Garibaldi R. Infections and antibiotic resistance in nursing homes. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(1):1–17.

Nicolle LE. Urinary tract infections in long-term–care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(3):167–75.

Nace DA, Drinka PJ, Crnich CJ. Clinical uncertainties in the approach to long term care residents with possible urinary tract infection. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(2):133–9.

Nicolle LE, Henderson E, Bjornson J, McIntyre M, Harding GK, MacDonell JA. The association of bacteriuria with resident characteristics and survival in elderly institutionalized men. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106(5):682–6.

Loeb M, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, McGeer A, Simor A, Stevenson K, et al. Effect of a multifaceted intervention on number of antimicrobial prescriptions for suspected urinary tract infections in residents of nursing homes: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;331(7518):669.

Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643–54.

Nelson JM, Good E. Urinary tract infections and asymptomatic bacteriuria in older adults. Nurse Pract. 2015;40(8):43–8.

Sundvall PD, Elm M, Gunnarsson R, Mölstad S, Rodhe N, Jonsson L, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in urinary pathogens among Swedish nursing home residents remains low: a cross-sectional study comparing antimicrobial resistance from 2003 to 2012. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14(1):30.

Balogun SA, Philbrick JT. Delirium, a Symptom of UTI in the Elderly: Fact or Fable? A Systematic Review. Can Geriatr J. 2014;17(1):22–6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377–84.

Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–8.

Björkelund KB, Larsson S, Gustafson L, Andersson E. The Organic Brain Syndrome (OBS) scale: a systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied sciences. 2006;21(3):210–22.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). Washington: American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

McGeer A, Campbell B, Emori TG, Hierholzer WJ, Jackson MM, Nicolle LE, et al. Definitions of infection for surveillance in long-term care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 1991;19(1):1–7.

Loeb M, Bentley DW, Bradley S, Crossley K, Garibaldi R, Gantz N, et al. Development of minimum criteria for the initiation of antibiotics in residents of long-term–care facilities: results of a consensus conference. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22(02):120–4.

Bail K, Berry H, Grealish L, Draper B, Karmel R, Gibson D, et al. Potentially preventable complications of urinary tract infections, pressure areas, pneumonia, and delirium in hospitalised dementia patients: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6):e002770.

Bail K, Goss J, Draper B, Berry H, Karmel R, Gibson D. The cost of hospital-acquired complications for older people with and without dementia; A retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):91.

Adunsky A, Nenaydenko O, Koren-Morag N, Puritz L, Fleissig Y, Arad M. Perioperative urinary retention, short-term functional outcome and mortality rates of elderly hip fracture patients. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(1):65–71.

Briggs R, Coughlan T, Collins R, O'Neill D, Kennelly SP. Nursing home residents attending the emergency department: clinical characteristics and outcomes. QJM. 2013;106(9):803–8.

Flood KL, Rohlfing A, Le CV, Carr DB, Rich MW. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an inpatient cardiology ward. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(6):394–400.

Gallerani M, Manfredini R. Seasonal variation in the occurrence of delirium in patients admitted to medical units of a general hospital in Italy. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2013;25(3):179–83.

Haavisto M, Geiger U, Mattila K, Rajala S. A health survey of the very aged in Tampere, Finland. Age and Ageing. 1984;13(5):266–72.

Hanna SJ, Woolley R, Brown L, Kesavan S. The coming of age of a joint elderly medicine-psychiatric ward: 18 Years' experience. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(1):148–51.

Hartley S, Valley S, Kuhn L, Washer LL, Gandhi T, Meddings J, et al. Inappropriate testing for urinary tract infection in hospitalized patients: an opportunity for improvement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(11):1204–7.

Honney K, Trepte NJB, Parker RA, Patel J, Mallinson R, Sultanzadeh SJ, et al. Characteristics and determinants of survival in oldest old nursing home residents admitted to hospital with an acute illness compared to their younger counterparts. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2014;26(2):153–60.

Kallin K, Jensen J, Olsson LL, Nyberg L, Gustafson Y. Why the elderly fall in residential care facilities, and suggested remedies. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(1):41–52.

Leis JA, Gold WL, Daneman N, Shojania K, McGeer A. Downstream impact of urine cultures ordered without indication at two acute care teaching hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(10):1113–4.

Levy CR, Eilertsen T, Kramer AM, Hutt E. Which clinical indicators and resident characteristics are associated with health care practitioner nursing home visits or hospital transfer for urinary tract infections? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(8):493–8.

Mentes JC, Culp K. Reducing hydration-linked events in nursing home residents. Clin Nurs Res. 2003;12(3):210–25.

Videcnik Zorman J, Lusa L, Strle F, Maraspin V. Bacterial infection in elderly nursing home and community-based patients: a prospective cohort study. Infection. 2013;41(5):909–16.

Caljouw MA, den Elzen WP, Cools HJ, Gussekloo J. Predictive factors of urinary tract infections among the oldest old in the general population. A population-based prospective follow-up study. BMC Med. 2011;9:57.

Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerström L, Olofsson B. Do urinary tract infections affect morale among very old women? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):73.

Lee CC, Chen SY, Chang IJ, Chen SC, Wu SC. Comparison of clinical manifestations and outcome of community-acquired bloodstream infections among the oldest old, elderly, and adult patients. Medicine. 2007;86(3):138–44.

Shacham N, Lerman Y, Justo D. Low Norton scale scores are associated with medical complications other than pressure ulcers during rehabilitation in the elderly. Eur Geriatr Med. 2013;4(2):91–4.

Caterino JM, Weed SG, Espinola JA, Camargo CA Jr. National trends in emergency department antibiotic prescribing for elders with urinary tract infection, 1996-2005. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(6):500–7.

Culp K, Mentes J, Wakefield B. Hydration and acute confusion in long-term care residents. West J Nurs Res. 2003;25(3):251–66 discussion 267-273.

Gonen I, Umul ME, Kaya ON, Temel EN, Kose SA, Unal O, et al. Clinical and laboratory evaluation of urinary tract infections in elderly population. Acta Med Austriaca. 2013;29:853–8.

Hartley S, Valley S, Kuhn L, Washer LL, Gandhi T, Meddings J, et al. Overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria: identifying targets for improvement. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(4):470–3.

Malyuk RE, Wong C, Buree B, Kang A, Kang N. The interplay of infections, function and length of stay (LOS) in newly admitted geriatric psychiatry patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):251–5.

Barkham TM, Martin FC, Eykyn SJ. Delay in the diagnosis of bacteraemic urinary tract infection in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 1996;25(2):130–2.

Hufschmidt A, Shabarin V, Rauer S, Zimmer T. Neurological symptoms accompanying urinary tract infections. Eur Neurol. 2010;63(3):180–3.

Mariconda M, Costa GG, Cerbasi S, Recano P, Aitanti E, Gambacorta M, et al. The determinants of mortality and morbidity during the year following fracture of the hip: a prospective study. Bone Jt J. 2015;97B(3):383–90.

Alavi SM, Moogahi S. Confusion and fever in the elderly: the necessity of lumbar puncture for CSF examination. Pak J Med Sci. 2008;24(4):520–4.

Cogdill B, Ross C, Hurst J, Garrison K, Drayton S, Wisniewski C. Evaluation of urinalyses ordered for diagnosis of urinary tract infections at an inpatient psychiatric hospital. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2014;47(1):17–24.

Ducharme J, Neilson S, Ginn JL. Can urine cultures and reagent test strips be used to diagnose urinary tract infection in elderly emergency department patients without focal urinary symptoms? CJEM. 2007;9(2):87–92.

Warshaw G, Tanzer F. The effectiveness of lumbar puncture in the evaluation of delirium and fever in the hospitalized elderly. Arch Fam Med. 1993;2(3):293–7.

Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerström L, Olofsson B. Prevalence and factors associated with urinary tract infections (UTIs) in very old women. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50(2):132–5.

Bellelli G, Bernardini B, Pievani M, Frisoni GB, Guaita A, Trabucchi M. A score to predict the development of adverse clinical events after transition from acute hospital wards to post-acute care settings. Rejuvenation Res. 2012;15(6):553–63.

Lixouriotis C, Peritogiannis V. Delirium in the primary care setting. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(1):102–4.

Boockvar K, Signor D, Ramaswamy R, Hung W. Delirium during acute illness in nursing home residents. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(9):656–60.

George J, Bleasdale S, Singleton SJ. Causes and prognosis of delirium in elderly patients admitted to a district general hospital. Age Ageing. 1997;26(6):423–7.

Assantachai P, Suwanagool S, Gherunpong V, Charoensook B. Urinary tract infection in the elderly: a clinical study. J Med Assoc Thail. 1997;80(12):753–9.

Schultz BM, Gambert SR. Influence of chronic disease on the presentation of urinary tract infections in the institutionalized elderly. AGE. 1991;14(3):79–81.

Silver SA, Baillie L, Simor AE. Positive urine cultures: a major cause of inappropriate antimicrobial use in hospitals? Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2009;20(4):107–11.

Caterino JM, Ting SA, Sisbarro SG, Espinola JA, Camargo CA Jr. Age, nursing home residence, and presentation of urinary tract infection in U.S. emergency departments, 2001-2008. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(10):1173–80.

Collins N, Blanchard MR, Tookman A, Sampson EL. Detection of delirium in the acute hospital. Age Ageing. 2010;39(1):131–5.

Levkoff SE, Safran C, Cleary PD, Gallop J, Phillips RS. Identification of factors associated with the diagnosis of delirium in elderly hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36(12):1099–104.

Lin RY, Heacock LC, Bhargave GA, Fogel JF. Clinical associations of delirium in hospitalized adult patients and the role of on admission presentation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(10):1022–9.

Lin RY, Heacock LC, Fogel JF. Drug-induced, dementia-associated and non-dementia, non-drug delirium hospitalizations in the United States, 19982005: an analysis of the national inpatient sample. DrugsAging. 2010;27(1):51–61.

Manepalli J, Grossberg GT, Mueller C. Prevalence of delirium and urinary tract infection in a psychogeriatric unit. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1990;3(4):198–202.

Rothberg MB, Herzig SJ, Pekow PS, Avrunin J, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. Association between sedating medications and delirium in older inpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):923–30.

Culp K, Tripp-Reimer T, Wadle K, Wakefield B, Akins J, Mobily P, et al. Screening for acute confusion in elderly long-term care residents. J Neurosci Nurs. 1997;29(2):86–8 95-88100.

Gau JT, Shibeshi MR, Lu IJ, Rafique M, Heh V, Meyer D, et al. Interexpert agreement on diagnosis of bacteriuria and urinary tract infection in hospitalized older adults. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(4):220–6.

Sundvall PD, Elm M, Ulleryd P, Molstad S, Rodhe N, Jonsson L, et al. Interleukin-6 concentrations in the urine and dipstick analyses were related to bacteriuria but not symptoms in the elderly: a cross sectional study of 421 nursing home residents. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:88.

Sundvall PD, Ulleryd P, Gunnarsson RK. Urine culture doubtful in determining etiology of diffuse symptoms among elderly individuals: a cross-sectional study of 32 nursing homes. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:36.

Eriksson I, Gustafson Y, Fagerstrom L, Olofsson B. Urinary tract infection in very old women is associated with delirium. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):496–502.

Laurila JV, Laurila JV, Laakkonen M-L, Timo SE, Reijo TS. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in a frail geriatric population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;65(3):249–54.

Marcantonio ER, Kiely DK, Simon SE, John Orav E, Jones RN, Murphy KM, et al. Outcomes of older people admitted to postacute facilities with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(6):963–9.

Sabzwari S, Kumar D, Bhanji S, Sheerani M, Azhar G. Proportion, Predictors and Outcomes of Delirium at a Tertiary care Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Ageing Int. 2014;39(1):33–45.

Ariathianto Y. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: prevalence in the elderly population. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40(10):805.

Fulop T, Larbi A, Witkowski JM, McElhaney J, Loeb M, Mitnitski A, et al. Aging, frailty and age-related diseases. Biogerontology. 2010;11(5):547–63.

Castell MV, Sanchez M, Julian R, Queipo R, Martin S, Otero A. Frailty prevalence and slow walking speed in persons age 65 and older: implications for primary care. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:86.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank James Cook University for their support in conducting this review, facilitating the access to many full text articles.

Funding

Funding for the project was provided by the James Cook University College of Medicine and Dentistry. This facilitated the purchasing of some full text articles.

Availability of data and materials

PubMed, Scopus and PsycINFO (via ProQuest).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RG contributed to the conception of the review, with SM, AB, PDS and RG being involved in the design of the review. SM accessed the journal databases, performed the search strategy and assessed the articles for eligibility. Data extraction was performed by SM and AB. Risk of bias was assessed by SM and AB, with any discrepancies being resolved by consensus or discussion with RG. Final manuscript was prepared by SM, with drafts reviewed by AB. RG and PDS were involved in revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. The final manuscript was reviewed and approved by all authors. SM, AB, PDS and RG.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval from a Human Research Ethics Committee was not sought as this was a systematic review of the published literature.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

Authors PDS and RG have previous publications cited in this systematic literature review.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mayne, S., Bowden, A., Sundvall, PD. et al. The scientific evidence for a potential link between confusion and urinary tract infection in the elderly is still confusing - a systematic literature review. BMC Geriatr 19, 32 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1049-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1049-7