Abstract

Background

Systems for identifying potentially inappropriate medications in older adults are not immediately transferrable to advanced dementia, where the management goal is palliation. The aim of the systematic review was to identify and synthesise published systems and make recommendations for identifying potentially inappropriate prescribing in advanced dementia.

Methods

Studies were included if published in a peer-reviewed English language journal and concerned with identifying the appropriateness or otherwise of medications in advanced dementia or dementia and palliative care. The quality of each study was rated using the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist. Synthesis was narrative due to heterogeneity among designs and measures. Medline (OVID), CINAHL, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005 – August 2014) and AMED were searched in October 2014. Reference lists of relevant reviews and included articles were searched manually.

Results

Eight studies were included, all of which were scored a high quality using the STROBE checklist. Five studies used the same system developed by the Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer Care Efforts (PEACE) Program. One study used number of medications as an index, and two studies surveyed health professionals’ opinions on appropriateness of specific medications in different clinical scenarios.

Conclusions

Future research is needed to develop and validate systems with clinical utility for improving safety and quality of prescribing in advanced dementia. Systems should account for individual clinical context and distinguish between deprescribing and initiation of medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Advanced dementia infers a range of physical and psychosocial needs [1]. A palliative approach that maximises comfort is considered best practice [2]. Medication use should be focused on symptom relief and quality of life rather than treating secondary conditions where burden is likely to outweigh clinical benefit [2].

Most research on potentially inappropriate prescribing has focused on the elderly rather than dementia specifically. The harm/benefit risk ratios of numerous medications are unfavourably affected by age-related changes in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters [3]. Biological changes can result in medications having longer durations of action, greater risks of toxicity, and increased frequencies of adverse effects.

Several systems for identifying potentially inappropriate medications in older adults have been developed to operationally define the harm/benefit risk in clinical practice and research [4, 5]. These systems have been applied in early but not advanced dementia [6, 7]. Generalizability to people with advanced dementia is limited by pathophysiological changes as dementia progresses and the fact that systems have not been developed for use where goals of care are palliative. In advanced dementia, there is an exaggerated decrease in total body water and muscle and an increase in relative adipose tissue [8]. These changes are additional to the changes due to aging and have a direct and variable impact on the metabolism of drugs [9]. This means that individuals with advanced dementia may be more prone to adverse drug effects and drug-drug interactions than other older people [10]. People with advanced dementia are also less able than others to report adverse effects or to be involved in decision-making about whether to initiate or withdraw medications. Finally, individuals with advanced dementia have typically been excluded from research examining quality use of medications in older populations, limiting evidence regarding benefits and harms. Identifying potentially inappropriate medications to guide prescribing practice for people with advanced dementia is therefore likely to face challenges over and above those for older populations more generally.

A review by Parsons et al. (2010) summarised literature on specific medication types proposed to be potentially inappropriate for people with dementia nearing the end of life, and examined decision-making regarding medication discontinuation [9]. Potentially inappropriate medications were identified to include anticholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, antipsychotics, statins, antibacterials, antihypertensives, antihyperglycaemic agents, anticoagulants and medications to manage osteoporosis. Parsons et al. highlighted the lack of guidance on identifying potentially inappropriate medications and when and how to safely discontinue medications at the end of life.

A distinct but related concept is polypharmacy. Polypharmacy refers to the combination of multiple medications which may lead to cumulative adverse effects and antagonistic drug-drug interactions where a worse adverse effect is produced than either drug could have caused alone [11]. Polypharmacy can lead to worse side effects in the same domain (e.g. if receiving several psychoactive medications) or more side effects across different domains (e.g. if receiving a psychoactive medication and a blood pressure medication). Each of the medications involved may or may not be deemed potentially inappropriate on their own.

The current authors set out to update the review by Parsons et al. using a more rigorous systematic methodology and specifically aiming to identify and synthesise any published systems and recommendations for identifying potentially inappropriate prescribing in people with advanced dementia.

Methods

This systematic review was undertaken in adherence with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) Statement [12].

Eligibility criteria

Articles needed to be published in a peer-reviewed English language journal and report on a system or recommendations for identifying the appropriateness or otherwise of medications in advanced dementia or dementia and palliative care.

Information sources

Electronic databases Medline (OVID), CINAHL, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005 – August 2014) and AMED were searched in October 2014. Reference lists of the review by Parsons et al. (2010) and included articles were searched by hand.

Search

Database searches used keyword searches and medical subject headings (MeSH) based on terms used by Parsons et al. (2010) but further terms were also added as detailed in Table 1.

Study selection

Two researchers (DD, TL) independently applied the eligibility criteria to 10 % of search results and checked inter-rater reliability. After finding 100 % agreement, a single investigator (DD) rated the remaining 90 % articles alone. Full-texts were reviewed where a decision could not be made on abstract and title alone.

Data collection and items

Data were extracted from eligible studies by a single researcher (DD) using a standardised template. Data items extracted included: study design, aims, setting, sample size and characteristics, details of the approach taken to identifying inappropriate medications, and outcome variables related to inappropriate prescribing.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The quality of each study was rated independently by two researchers (DD and TL) using criteria from the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [13]. Any disagreements were resolved via discussion.

Synthesis

Expected heterogeneity among designs and methods meant that synthesis needed to be narrative rather than via meta-analysis. Methods for narrative synthesis were based on techniques described by Popay et al. (2006) [14].

Results

Study selection

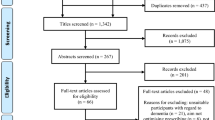

Database searches identified 882 records once duplicates were removed. Five articles were included for analysis from electronic database searches [15–19], and a further three articles were additionally identified through hand searching [20–22]. See Fig. 1 for more details.

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the eight studies included in this review are summarised in Table 2. The studies variously aimed to: 1) determine the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in aged care residents with advanced dementia [15–18, 20, 22], 2) identify the factors associated with likelihood of potentially inappropriate medications [16–18, 20, 22], and 3) explore the perceptions of healthcare professionals regarding factors determining medication-related decision-making in this population [19, 21].

Five studies were undertaken in the USA [15–17, 19, 22] and three were undertaken in European countries [18, 20, 21].

Study designs included two cross-sectional surveys [19, 21], three prospective cohort studies [15, 17, 18], one of which reported the cross-sectional results of medication data collected at baseline [18], two retrospective clinical record audits [20, 22], and one combining a retrospective clinical record audit with a consensus panel component [16].

Six studies analysed medication data from a total of 7457 participants with advanced dementia, their age ranging from 57 to 100 years of age and the majority being female, ranging from 55.2 % [15] to 87.5 % [17] of their samples. Of these, four studies focused solely on nursing homes [15–17, 20, 22] while two also included people with advanced dementia receiving home care [18, 20].

Risk of bias within studies

The eight studies included in the systematic review were generally of high quality as rated by STROBE criteria, complying with 76 % [16] to 100 % [17, 22] of criteria. However, Toscani et al. (2013) did not indicate the study’s design in the title or abstract [18], and Colloca et al. (2012) did not sufficiently explain a larger study’s design from which their data were drawn [20]. Four studies did not give a rationale for sample size [15, 16, 20, 21]. Three studies did not attempt to address potential sources of bias [15, 16, 21]. These same three studies also provided limited descriptions of statistical methods or how they dealt with missing data. Three studies did not provide unadjusted results for their multivariate analyses [16, 18, 20], and one controlled only for gender and age rather than other socio-demographic, clinical and nursing home variables [18]. Two studies did not discuss the generalizability of their results [18, 19].

Synthesis of results

Five of the eight studies [16–18, 20, 22] used the same system for identifying potentially inappropriate medications – that was developed by the Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer Care Efforts (PEACE) Program reported by Holmes et al. (2008) [16]. In the PEACE program, medications were audited for 34 patients with advanced dementia where a palliative approach was deemed appropriate. In a three-round modified Delphi process, 12 geriatricians rated each medication identified via the audit as ‘never’, ‘rarely’, ‘sometimes’ or ‘always’ appropriate. Consensus for a medication or medication class was defined as agreement on categorisation by >50 % (i.e. at least 7/12) participants. See Table 3 for drug classes in each category according to the final consensus.

Following Holmes and colleagues’ preliminary study [16], four other international studies utilised [17, 18, 20, 22] the PEACE criteria to rate the appropriateness of medications taken by large cohorts of aged care residents with advanced dementia and examine predictors of taking ‘never’ appropriate medications among socio-demographic and clinical variables. See Table 4 for a summary of these studies’ samples and results.

Blass et al. (2008) used a more rudimentary index of potentially inappropriate prescribing in people with advanced dementia based purely on number of medications [15]. The study identified that nursing home residents with advanced dementia received a mean of 14.6 medications (±7.4) and that, as residents approached death, the type but not number of medications altered. The study identified an increase in medications for symptom control (i.e. opioids and laxatives) and a decrease in medications for comorbid conditions (i.e. antibiotics, anti-dementia drugs, cardiovascular agents and psychotropic agents).

Two studies by Shega et al. (2009) and Parsons et al. (2014) explored factors influencing medication-related decisions by physicians (hospital medical directors [19], general practitioners and hospital physians [21]), specifically their continuation or discontinuation in dying patients with dementia [19, 21]. Physicians from both studies recommended discontinuation of anticholinesterase inhibitors and memantine because of perceived lack of clinical benefit during end-stage of illness [21], but were less likely to recommend this if there was any indication that they stabilised cognition, reduced challenging behaviours or maintained patient function [19]. Physicians also recommended discontinuing quetiapine and simvastatin because of a perceived lack of indication and/or risk of adverse effects such as confusion [21]. Emphasis was placed on ensuring patient comfort and symptom management and reducing polypharmacy and preventative treatments.

Discussion

This systematic review identified only one system for identifying potentially inappropriate medications in people with advanced dementia that had any degree of validation – the PEACE criteria developed by Holmes et al. (2008) [16]. A second system we identified relied on number of medications alone [15]. Finally, two other studies have sought to understand the decision-making process of health professionals when determining the appropriateness of medications in end-stage dementia.

Whilst providing a useful foundation, the PEACE criteria are limited in a number of ways. Holmes et al. (2008) themselves identified a need for further validation of the system by means of a larger sample of medication data and a more representative expert panel of health professionals. Their expert informants were all geriatricians from the University of Chicago. Moreover, Holmes et al. (2008) did not report informants’ rationale for medication classification within the system. Authors using the PEACE criteria since have highlighted its ‘one size fits all’ approach and the importance of taking into account each older individual’s life expectancy [17, 18, 20], comorbidities, symptom experience [16, 22] and goals of care [18]. These concerns are especially applicable to the PEACE categories of ‘sometimes’ and ‘rarely’ appropriate, which are of limited usefulness without a better understanding of factors influencing decision-making.

Studies using the PEACE criteria suggest insights into how this system might be refined and validated in the future. Percentages of residents ‘never’ appropriate medications varied between studies. In addition to differences in prescribing cultures between countries and organisations included in these studies, differences in rates of never appropriate medications may have resulted in part from variability in the methods used to define advanced dementia and code medications. Three studies used the Cognitive Performance Scale (CPS) [17, 20, 22] to define advanced dementia while two others used the Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST) [16, 18]. With regard to coding medications, two studies used the Anatomical Therapeutic Classification (ATC) System [18, 20] and two used the British National Formulary [17, 22]; both these approaches differed from the original study, which utilised the British National Formulary, United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary and the Lexi-Comp alphabetical drug index [16]. While Colloca et al. did not provide a list of ATC codes they included, Toscani et al. indicated that ATC codes (beginning with N06DA) for anti-dementia drugs (rivastigmine, donepezil and galantamine) were allocated to “central nervous system stimulants” thereby placing these medications under the PEACE category ‘no consensus.’ However Colloca et al. may have allocated the same ATC codes to “acetylcholinesterase inhibitors,” placing them under the PEACE category ‘never appropriate,’ and may explain the difference in proportions of residents receiving never appropriate medications between studies. However, despite such differences between inclusion criteria and methods, findings from studies using the PEACE criteria have in some cases been surprisingly consistent with three studies reporting the most commonly prescribed ‘never’ appropriate medications as anticholinesterase inhibitors and lipid-lowering agents [17, 20, 22].

The authors of several studies in our review interpreted their results as indicating that people with advanced dementia undergo excessive pharmacological treatment [15, 16, 20, 22]. The reasons speculated included a lack of evidence-based guidance for clinicians [15, 20–22], a hesitancy among health professionals to take patients off medications where the impact has not been formally evaluated in advanced dementia [15, 19, 21], and the possibility that prescribers may not have recognised advanced dementia as a terminal illness needing to be treated with a palliative approach [18]. It may also be that discussions about reducing medications are sometimes avoided by health professionals because they require acknowledgement that the person with dementia is nearing the end of life [23]. This particular challenge has been identified in other palliative populations across a range of settings. Collier et al. (2013) have created a model to provide a systematic framework for hospice clinicians to have difficult conversations with patients, families and interdisciplinary clinical colleagues about the need to change prescribing when clinical decline occurs [23]. While broadly developed for individuals receiving end of life care, it may be applied to individuals with advanced dementia in order to facilitate discussion and improve care.

The widely held view that polypharmacy is undesirable in advanced dementia and end of life care is consistent with evidence that number of medications is related to adverse outcomes such as delirium, cognitive decline and loss of appetite [24]. However, when used in isolation (as by Blass et al. [2008] [15]), number of medications is too simplistic to be a useful index of the safety and quality of prescribing in advanced dementia. Both Blass et al. themselves and Tjia et al. found that the type but not number of medications changed over time as individuals with advanced dementia approached death, and a cross-sectional study has found that patients taking fewer than eight medications were more likely to be underusing a potentially useful medication [25]. The aim of palliative prescribing is to support comfort and quality of life, and in many cases, medications may need to be added to mitigate symptoms [23].

Reducing numbers of medications at the end of life also requires due attention to complexities inherent in deprescribing. While medications can be withdrawn safely, there is a risk of withdrawal reactions, symptom recurrence or reactivation of underlying disease [26]. Evidence is lacking in advanced dementia, however there is a growing body of research on the potential benefits of deprescribing in older people more generally [26]. It was shown that medication classes for secondary prevention such as lipid-lowering agents, antibiotics, antihypertensives and psychotropics can be withdrawn in older patients without causing harm. A system has been developed to inform deprescribing in disabled older adults in the form of an algorithm for decision-making [27]. Drug discontinuation based on this algorithm has been found not to increase significant adverse events, and only 10 % of the drugs ceased had to be readministered because of the return of the original indication for the drug. The same authors also tested their deprescribing algorithm in older adult community dwellers and were able to successfully deprescribe medications in 81 % of their sample with no significant adverse events or deaths attributable to discontinuation [28]. Future work is needed to examine the applicability of this algorithm to people with advanced dementia specifically and adapt as necessary.

First and foremost, this review is limited by the small pool of studies found that have focused on identifying potentially inappropriate medications in people with advanced dementia, limiting the avenues available for synthesis and conclusion. In particular, the absence of any studies validating systems against clinical outcomes necessarily limits the evidence base for improving the safety and quality of medication use in advanced dementia. Methodological limitations of the review include not requiring the primary aim of included studies to match those of this review and the possibility that we may not have identified all relevant research in the field. Whilst we expanded the search terms used by a previous review [9] and took a systematic approach to inclusion/exclusion, articles in the field of deprescribing are notoriously difficult to find [29], and nearly half the articles included in this study were found through hand searching rather than through databases.

Conclusion

While there are well-accepted criteria available for identifying potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, these cannot be readily applied to the case of advanced dementia, where there are disease-specific concerns and a palliative approach is needed. The PEACE criteria show promise for further development, but require further studies to elucidate how decision-making should be informed by individual clinical context and how considerations may differ between deprescribing versus initiation. Further studies are also needed to identify potentially inappropriate medications with reference to empirical data on adverse events and other negative outcomes, rather than solely relying on the perceptions of health professionals and data and theory relating to standard pharmacological theory. Finally, studies are needed to test the ability of systems to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing to improve the quality and safety of medication use in people with advanced dementia.

Abbreviations

AMED, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Classification system; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CPS, Cognitive Performance Scale; FAST, Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST); MeSH, Medical Subject Headings; PEACE, Palliative Excellence in Alzheimer Care Efforts program; PRISMA, Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses statement; STROBE, STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology checklist

References

Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Jones RN, Prigerson HG, Volicer L, Givens JL, Hamel MB. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–38.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Boland B, Rexach L. Drug therapy optimization at the end of life. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(6):511–21.

Dedhiya SD, Hancock E, Craig BA, Doebbeling CC, Thomas 3rd J. Incident use and outcomes associated with potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(6):562–70.

Fick DM, Semla TP. 2012 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria: New Year, New Criteria, New Perspective. JAGS. 2012;60(4):614–5.

Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. STOPP (Screening Tool of Older Persons’ potentially inappropriate Prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):673–9.

Bosboom PR, Alfonso H, Almeida OP, Beer C. Use of Potentially Harmful Medications and Health-Related Quality of Life among People with Dementia Living in Residential Aged Care Facilities. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2012;2(1):361–71.

Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Shega JW, Rademaker A, Weintraub S. Functional decline associated with polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older adults with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2011;26(8):606–15.

Lau DT, Mercaldo ND, Harris AT, Trittschuh E, Shega J, Weintraub S. Polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among community-dwelling elders with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(1):56–63.

Parsons C, Hughes CM, Passmore AP, Lapane KL. Withholding, discontinuing and withdrawing medications in dementia patients at the end of life: a neglected problem in the disadvantaged dying? Drugs Aging. 2010;27(6):435–49.

Riker GI, Setter SM. Polypharmacy in older adults at home: what it is and what to do about it--implications for home healthcare and hospice. Home Healthc Nurse. 2012;30(8):474–85. quiz 486–477.

Verrue CL, Petrovic M, Mehuys E, Remon JP, Vander Stichele R. Pharmacists' interventions for optimization of medication use in nursing homes : a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(1):37–49.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247–51.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: Final report. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster, UK: University of Lancaster; 2006;15(1):047–71.

Blass DM, Black BS, Phillips H, Finucane T, Baker A, Loreck D, Rabins PV, Blass DM, Black BS, Phillips H, et al. Medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):490–6.

Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Shega JW, Hougham GW, Cox Hayley D, Dale W. Integrating palliative medicine into the care of persons with advanced dementia: identifying appropriate medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(7):1306–11.

Tjia J, Rothman MR, Kiely DK, Shaffer ML, Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Mitchell SL. Daily medication use in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):880–8.

Toscani F, Di Giulio P, Villani D, Giunco F, Brunelli C, Gentile S, Finetti S, Charrier L, Monti M. Treatments and prescriptions in advanced dementia patients residing in long-term care institutions and at home. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(1):31–7.

Shega JW, Ellner L, Lau DT, Maxwell TL. Cholinesterase inhibitor and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor antagonist use in older adults with end-stage dementia: a survey of hospice medical directors. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(9):779–83.

Colloca G, Tosato M, Vetrano DL, Topinkova E, Fialova D, Gindin J, van der Roest HG, Landi F, Liperoti R, Bernabei R. Inappropriate drugs in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment: results from the shelter study. PLoS One. 2012;7(10), e46669.

Parsons C, McCorry N, Murphy K, Byrne S, O'Sullivan D, O'Mahony D, Passmore P, Patterson S, Hughes C. Assessment of factors that influence physician decision making regarding medication use in patients with dementia at the end of life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;29(3):281–90.

Tjia J, Briesacher BA, Peterson D, Liu Q, Andrade SE, Mitchell SL. Use of Medications of Questionable Benefit in Advanced Dementia. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014

Collier KS, Kimbrel JM, Protus BM. Medication appropriateness at end of life: a new tool for balancing medicine and communication for optimal outcomes--the BUILD model. Home Healthc Nurse. 2013;31(9):518–24. quiz 524–516.

Casey DA, Northcott C, Stowell K, Shihabuddin L, Rodriguez-Suarez M. Dementia and palliative care. Clin Geriatr. 2012;20(1):36–41.

Steinman MA, Seth Landefeld C, Rosenthal GE, Berthenthal D, Sen S, Kaboli PJ. Polypharmacy and prescribing quality in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1516–23.

Beer C, Loh P, Peng YG, Potter K, Millar A. A pilot randomized controlled trial of deprescribing. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2011;2(2):37–43.

Garfinkel D, Zur-Gil S, Ben-Israel J. The war against polypharmacy: a new cost-effective geriatric-palliative approach for improving drug therapy in disabled elderly people. Isr Med Assoc J. 2007;9(6):430–4.

Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1648–54.

Iyer S, Naganathan V, McLachlan AJ, Le Conteur DG. Medication withdrawal trials in people aged 65 years and older. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1021–31.

Palliative Care PubMed Searches. [http://www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/tabid/322/Default.aspx].

Thompson W, Farrell B. Deprescribing: what is it and what does the evidence tell us? Can J Hosp Pharm. 2013;66(3):2.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Availability of data and materials

Details on the results of our database searches and data extraction are available from the corresponding author on request.

Authors’ contributions

DD contributed to the development of the search strategy, conducted the search, analysed the articles, and drafted the manuscript. TL and MA contributed to the development of the search strategy, analysed the articles, and helped to draft the manuscript. AB and PD contributed to analysis of data. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Disalvo, D., Luckett, T., Agar, M. et al. Systems to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing in people with advanced dementia: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr 16, 114 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0289-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0289-z