Abstract

Background

Dementia is an increasing public health challenge, and the number of individuals affected is growing rapidly. Mental disorders and symptoms of mental distress have been reported to be risk factors for dementia. The aim of this study was to examine whether midlife mental distress is a predictor for onset of dementia later in life.

Methods

Using data from a large population-based study (The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study; HUNT1) linked to a dementia registry (The Health and Memory study; HMS) enabling a maximum 27 years of follow-up, we ascertained mental distress and subsequent dementia status for 30,902 individuals aged 30–60 years at baseline. In HUNT1, self-reported mental distress was assessed using the four-item Anxiety and Depression Index (ADI-4). Dementia status was ascertained from HMS, which included patient and caregiver history, cognitive testing and clinical and physical examinations from the hospitals and nursing homes serving the catchment area of HUNT1. In the main analysis, unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were computed for the prospective association between mental distress and dementia. In secondary analyses, two-way age and gender interactions with mental distress on later dementia were examined.

Results

A 50% increased odds for dementia among HUNT1-participants reporting mental distress was found (crude odds ratio (OR): 1.52; 95% CI 1.15–2.01), and a 35% increase in the fully adjusted model (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.01-1.80). In secondary analyses, we found evidence for a two-way interaction with age on the association between mental distress and dementia (p = 0.030): the age- and gender adjusted OR was 2.44 (95% CI 1.18–5.05) in those aged 30–44 years at baseline, and 1.24 (0.91–1.69) in 45–60 year olds.

Conclusions

Our results indicate an association between midlife mental distress and increased risk of later dementia, an association that was stronger for distress measured in early compared to later midlife. Mental distress should be investigated further as a potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dementia is caused by a number of neurodegenerative disorders, most commonly Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in later life [1]. As the life expectancy of the global population increases, the number of individuals suffering from dementia is growing rapidly [2-5]. The personal and societal impacts of dementia are considerable [6-8], and it constitutes the third most common neuropsychiatric disorder in high income countries [9]. It is estimated that by 2040, about 80 million people worldwide will be affected by dementia [10] and there is a need for increased understanding of its aetiology and underlying mechanisms.

Pathology underlying dementia may be present for 10 years or more before the clinical onset [11,12], rendering it difficult to ascertain whether predictive factors in short-term follow-up studies are risk factors, or manifestations of preclinical disease [13]. Established risk factors for dementia include older age, female sex and genetic influences [14,15]. Furthermore, vascular factors have been strongly implicated for both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia [14]. Other putative risk factors include smoking [16], excessive alcohol consumption [17], oxidative and inflammatory stress [15], chemical exposure [18], adiposity [19,20], and head trauma [21]. Conversely, intellectual stimulation [22,23], social activity [23], higher education and socioeconomic status [24], a healthier diet [25,26] and moderate physical activity [27] have been suggested as potential protective factors. Due to the increasing number of individuals expected to suffering from dementia and the detrimental consequences, there has been increased interest in modifiable risk and protective factors related to dementia [28,29].

Depression is frequently found to be associated with dementia, and a 2001 review concluded that clinical depression should be viewed as an independent risk factor [30]. The mechanisms explaining this association are poorly understood [31], yet it is well known that depression is also associated with cognitive dysfunction and decline [32,33]. The role of anxiety in relation to dementia is not as well-documented, although a recent study suggested a role [34]. In the general population, however, the co-morbidity of anxiety and depression is large [35,36], and many symptoms are present in both conditions, making them hard to distinguish from each other. Consequently, symptoms of depression and anxiety can be understood as indicators of general mental distress [37]. Consistent with that assumption, a study by Johansen and colleagues recently suggested a relationship between midlife mental distress and higher subsequent risk of dementia [38,39]. This study had a follow-up of more than 30 years, but was limited in that the cohort only included females and mental distress was assessed by a single question. Barnes and colleagues also found that midlife mental distress was associated with both Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in a retrospective cohort study [31], although again the assessment of mental distress was primarily based on a single self-report question. Also, a study investigating mental distress in relation to the diagnosis of dementia at time of death, found that a higher score on the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) was associated with increased risk of dementia mortality – although the follow-up period was more limited [40].

The aim of this study was to examine whether midlife mental distress is associated with later dementia. Specifically, a general population-based study, in which self-reported mental distress had been recorded, was linked to a dementia registry in the same catchment area, enabling individual follow-up of up to 27 years.

Methods

Study population

In this study, data from the population-based Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT1), carried out in 1984–86 were linked to information on dementia status from the Health and Memory Study (HMS) ascertained in 1995–2011. Both studies were conducted in the same catchment area, the Nord-Trøndelag County in Norway.

Exposure, mental distress: the hunt1 study

The HUNT1 study was a large population-based survey of the general adult population of Nord-Trøndelag County, Norway [41,42]. HUNT1 was conducted between 1984 and 1986, and included physical examinations and self-report questionnaires on general health, health-related behaviours and socioeconomic information. Every citizen of Nord-Trøndelag County aged ≥20 years was invited to the health survey, and 77,212 people (89.4%) participated [42]. In HUNT1, attending and submitting oneself to the physical examination and answering the questionnaires was considered to be sufficient consent for participation [41]. The present study was approved by the Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics of Mid-Norway, Norway.

The population size in Nord-Trøndelag County has been relatively stable since HUNT1, and with the exception of young adults, the migration has been low [41], with a net out-migration during 1996–2000 of 0.3% per year [43].

The instrument used for assessing mental distress was the four-item Anxiety and Depression Index (ADI-4), described previously [44,45]. The instrument has been found to have reasonable performance when evaluated against the Hospital Anxiety and Depression rating scale (HADS-total score caseness (HADS-T): sensitivity 0.51; specificity = 0.93; Cohen’s ĸ = 0.55) [45]. HADS-T is a commonly used measure of mental health problems and includes 14 questions. A recent 10-year review recommended the use of HADS-T as a measure for mental distress [46].

The following four questions related to mental distress, as assessed by symptoms of anxiety and depression, were included in ADI-4:

-

Calmness: “Do you by and large feel calm and good?” 1) Most of the time, 2) Often, 3) Sometimes, 4) Never.

-

Nervousness: “During the last month, have you suffered from nervousness (felt irritable, anxious, tense or restless)?” 1) Never, 2) Sometimes, 3) Often, 4) Most of the time.

-

Vitality: “Do you feel, for the most part, strong and fit or tired and worn out?” 1) Very strong and fit, 2) Strong and fit, 3) Quite strong and fit, 4) Neither fit nor exhausted, 5) Tired and exhausted, 6) Quite tired and exhausted, 7) Very tired and exhausted.

-

Mood: “Would you say you are usually cheerful or downhearted?” 1) Very downhearted, 2) Downhearted, 3) Quite downhearted, 4) Neither cheerful nor downhearted, 5) Quite cheerful, 6) Cheerful, 7) Very cheerful.

The “nervousness” and “mood” scores were reversed before all four items were z-scored. The summed score of the items was categorised into a binary variable using the 88th percentile, as this cut-point has been shown to match the cut-off employed for HADS-Total caseness [45]. The Cronbach’s alpha in this population was 0.77, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was 0.78, and an exploratory factor analysis indicated that the four items had satisfactory loadings on a single factor (ranging from 0.64-0.71; factor eigenvalue 1.70).

Outcome, dementia status: the health and memory study

The primary aim of the Health and Memory Study (HMS) was to establish a dementia research registry in Nord-Trøndelag County, and included a comprehensive identification of dementia cases from hospitals and nursing homes covering Nord-Trøndelag County (see reference [47] for a detailed description). The HMS data were collected using two different procedures during the period of 1995–2011, namely: i) case note entries and ii) questionnaires and examinations. Firstly, a search of the electronic patient case notes of both hospitals serving the entire Nord-Trøndelag County was carried out to identify patients registered with a dementia diagnosis. The use of standardized dementia diagnostic procedures in these hospitals was established in 1998. Specialists in geriatric medicine and geriatric/old age psychiatry were responsible for the diagnostic procedures, and experienced geriatricians and old age psychiatrists validated the journal information retrieved for the purposes of establishing the dementia registry. The assessments of dementia status employed information regarding “both patient and caregiver history, clinical examinations, neuropsychological assessments, blood samples and imaging of the brain” ([47], p. 3). Secondly, all nursing home residents in Nord-Trøndelag were invited to participate (75.6% participation rate) in an extensive health examination with a particular focus on cognitive decline and dementia diagnosis. Using standardized interviews of the resident, the resident’s primary nurse and primary family caregiver, trained nurses assessed cognitive decline and potential presence of a dementia diagnosis.

The two data-sources; i) patients with dementia (n = 920), identified from hospital records of individuals referred to memory clinics in the two hospitals of Nord-Trøndelag County, and ii) patients with dementia (n = 620) examined in nursing homes in Nord-Trøndelag County, were combined for the purposes of this study. For a sub-group of the patients, crude information about retrospectively assessed age of onset of symptoms was also available for 306 (based on next of kin reporting retrospectively when they noticed the first symptoms of dementia). The assessment of dementia status in HMS adhered to national and international guidelines (such as ICD-10 criteria [48], the dementia with Lewy body (DLB) consortium criteria [49] and Manchester-Lund criteria [50]) and was based on patient and caregiver history, cognitive testing, and clinical and physical examinations [47]. Linkage between HUNT1 and the HMS was carried out using each participant’s personal identification number, and follow-up intervals ranged from 11 to 27 years. It has previously been established that participation rate in HUNT1 for patients diagnosed with dementia in Nord-Trøndelag County was 86%, and the mean age was 59 years at HUNT1 participation [47].

Potential confounders: the hunt1 study

A number of covariates were considered as potential confounders. The methods and instruments have been described in detail previously [42]. In short, socio-demographic information included registry-based information on age and gender from the Norwegian Tax Administration, and self-reported marital status (“married”, “single”, “divorced”, “separated” and “widower/widow”) and education (eight categories ranging from “7-years or less of basic schooling” to “more than 4 years at the college or university”) from HUNT1. We also included on-site measurements of diastolic and systolic blood pressure, as well as the number of self-reported cardiovascular disease (CVD) indicators counting affirmative answers on one or more of the following categories: “use of anti-hypertensive medication”, “diabetes”, “heart attack”, “angina pectoris” and “stroke”. Finally we included information about health-related behaviour, including frequency of alcohol consumption over the preceding 14 days (five categories ranging from abstainer to more than 10 times), daily smoking (yes/no) and physical activity (five categories ranging from “never” to “about every day”).

Statistical procedures

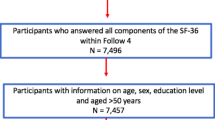

At baseline, 57,530 (74.5%) HUNT1 participants answered all of the ADI-4 items, and were eligible for further analysis. As we aimed to examine the prospective effect of mental distress prior to the development of dementia, all participants below 30 years and above 60 years at the HUNT1 participation were excluded. The reasoning behind this was that mental distress at age 60 or over could conceivably be a marker rather than a risk factor for dementia, and that risk of dementia would be negligible in persons younger than 30 years, even with more than two decades follow-up. Missing information on potential confounders ranged from 0.1% to 2.3%. This was imputed using a multivariate multiple imputation procedure with 10 imputations. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 for Windows, except where stated otherwise [51]. First, the characteristics of the study population were described and compared between those above and below the ADI-4 cut-off using bivariate statistics (independent t-tests for continuous variables and χ 2-tests for binary and categorical variables). Unadjusted and multivariate logistic regression models were computed to investigate the association between mental distress and subsequent dementia. In secondary analyses, the two-way age and gender interaction with mental distress on later dementia status was examined. Next, as ADI-4 was a compound measure of anxiety and depression symptoms, the association between the separate items comprising the ADI-4 were investigated as exposures in a sensitivity analysis. For the participants with subsequent dementia we also estimated the mean age (years) of symptom onset, as well as the time to onset (years) from HUNT1-participation. The crude main analysis was also investigated with structural equation modeling (SEM) with “mental distress” as a continuous latent construct in Mplus version 7 [52].

Additional analyses described and compared characteristics of those with valid responses on ADI-4 and those with one or more missing covariates or outcome, as well as the predicted probability of dementia across ADI-4 percentiles (see Additional file 1). Those who had missing responses on one or more of the ADI-4 items were somewhat younger (0.5 years), were less likely to be married, had higher blood pressure, and were less likely to report 1–4 times of alcohol consumption last 14 days. They also reported less smoking, lower levels of exercise and educational attainment. There were no differences in relation to dementia status between those with and without valid responses on ADI-4.

Ethics

The National Data Inspectorate and the Board of Research Ethics in Health Region IV of Norway approved HUNT and the current project.

Results

The HUNT1 participants included in the current study had a mean age of 43.8 years (standard deviation (SD) 8.8) at participation and 49.9% were female. At least one dementia case was identified for all 1-year bands within the inclusion baseline age range (30 to 60 years). The participants scoring above ADI-4 cut-off were older, more often female, and less likely to be married compared to those below the cut-off (all p-values <0.001). They also had higher diastolic blood pressure, reported more CVD-indicators, less frequent alcohol consumption, more smoking, less exercise and lower educational level (p < 0.001; see Table 1). HUNT1 participants who were later registered with dementia (N = 436; 1.41%) were older and more frequently female (both p-values <0.001) than participants without registered dementia at the end of follow-up. In addition, diastolic and systolic blood pressures at HUNT1 were also higher, and CVD indicators more often reported (all p-values <0.001), as well as lower alcohol consumption (p = 0.002), less smoking (p = 0.031), and lower educational attainment (p < 0.001) in participants with later registered dementia. There were no statistically significant differences in marital status or exercise in relation to dementia status.

In the crude main analyses, an increased odds for dementia among HUNT1-participants reporting mental distress (ADI-4 ≥ 88th percentile) compared to the remainder was identified (crude OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.15, 2.01; see Table 2). In the adjusted analyses, age was the principal confounding factor (age and gender adjusted OR 1.32; 95% CI 0.99, 1.75), and results were essentially the same in the fully adjusted model (adjusted for age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, blood pressure, CVD-indicators and health-related behaviours) (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.01, 1.80). The SEM analysis yielded similar results (crude standardized path coefficient 0.057, p = 0.004).

No statistical evidence for a gender interaction was found with mental distress on later dementia status (likelihood ratio test, p = 0.274). However, a significant two-way interaction was found between age and mental distress in relation to dementia (likelihood ratio test, p = 0.030 using age as a continuous variable). We therefore stratified for age in a post-hoc analysis, constructing two age-groups with the same range in years, age 30–44 (N = 17,843), and age 45–60 (N = 13,059). We found a stronger association between mental distress and dementia in the younger age-group (age- and gender-adjusted OR 2.44; 95% CI 1.18, 5.05), than in the older age-group (age- and gender-adjusted OR 1.24; 95% CI 0.91, 1.69). For the 306 dementia cases with available information on age of symptom onset, the 30–44 year group were also significantly younger when the symptoms first occurred (mean age 57.0 (95% CI 54.5, 59.5), compared to a mean age 73.0 (95% CI 72.2, 73.8) for the 45–60 year group, p < 0.001). There were no differences in the time from HUNT1 participation and onset (mean time to onset 18.1 years (95% CI 16.0, 20.2) in the 30–44.9 year group versus 18.2 (95% CI 17.6, 18.8) in the 45–60 year group, p = 0.919).

In sensitivity analyses, examining the predictive values of the individual ADI-4 items, three items predicted later dementia in unadjusted analyses (Nervousness, Vitality and Mood), but Nervousness was the only on remaining independent predictor in the age and gender-adjusted model (see Table 3).

Discussion

Main findings

In this population-based sample followed for over two decades there was some evidence for a prospective association between mid-life mental distress and dementia, but only marginally after adjustment for potential confounders. Age explained most of the examined association, but there was little evidence for any substantial confounding from the other included covariates. A stronger association was found between mental distress and dementia for individuals younger than 45 years at baseline compared to older HUNT1 participants. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between midlife mental distress assessed in a population-based study and subsequent dementia, with a follow-up of several decades for both males and females.

Interpretation of present findings

Given the insidious nature of dementia development [11,12], it cannot be ruled out that the associations identified in the present study are results of reverse causality (i.e. were early changes due to dementia impacts mental distress), even with a follow-up of between 11 and 27 years. There is evidence that pathology related to Alzheimer’s disease starts decades before clinical diagnosis [53,54]. In addition, although we were able to include several potentially important covariates in our analyses, residual confounding cannot be ruled out. Our findings are, however, in line with two previous studies, which both found a prospective association between midlife mental distress and dementia in women [38,39]. Also, another study found that proneness to mental distress was associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease in old age [55], and a fourth study found an association between mental distress and dementia deaths [40]. However, the results from our study are not consistent with those from a retrospective cohort study where self-reported depressive symptoms in late-life were more strongly associated with increased risk of dementia than symptoms in mid-life [31]. In contrast, our findings indicate that mental distress in early mid-life is more strongly associated with an increased risk for dementia, than mental distress measured in late mid-life. Participants aged >60 years were excluded from our study, as it was envisaged to be difficult to differentiate early symptoms of dementia from symptoms of mental distress in this group.

A number of neurological and cardiovascular mechanisms could explain the observed association between mental distress and risk of dementia, including structural and functional hippocampal damage [55], and other negative effects on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis [38,55], as well as hypertension as a potential mediator between mental distress and dementia [38]. Studies have indicated that there may be a two-way/bidirectional relationship between cardiovascular disease and depression [56,57], and this may also be true for mental distress in general. Further, midlife mental distress may be a result of increased vulnerability to stressors and dysfunctional coping strategies related to previous negative experience or genetic influences, which also constitute risk factors for dementia [39,58-60]. The finding from the sensitivity analysis that “Nervousness” was the only item independently associated with dementia after adjustment for age and gender, may suggest that this symptom of anxiety was the primary driver for dementia risk in our sample. Although this finding should be interpreted with caution, it does lend support to previous findings suggesting cortisol and exitotoxicity as a mechanism linking stress with dementia [61,62].

Associations between midlife mental distress and dementia may also be due to mental distress being a marker of rather than a risk factor for dementia [38]. Even for longer follow-up periods, there is evidence suggesting that the prodromal phase of dementia in some cases may be present several decades before dementia is manifest [54]. However, our age-stratified results, in which we found increased risk for dementia in the younger rather than the older group who reported mental distress, is not consistent with this. This may, however, be due to important differences in the characteristics of early (before 65 years of age) versus late-onset dementia (65 years or more), such as the disease progression, and symptom profile. During the past decades, it has become more common to differentiate between early- and late-onset dementia, each potentially associated with different epidemiology, genetics, clinical presentation and disease progression [63,64].

The differential association between mental distress and risk of dementia by age could potentially be related to differences in types and/or timing of onset of dementia. For example, midlife mental distress may be a more potent risk factor for earlier onset dementia. This notion may be supported by our finding that the younger group had a symptom onset on average 16 years earlier than the older group, while the time-to-dementia-onset was similar. The impact of mental distress on the development of dementia, if causal, might be affected by the duration of the distress, and as such, it may be that only prolonged mental distress has an effect on the risk of dementia [38,55]. In support of the greater impact of experiencing mental distress at younger age, early onset depressive disorder have been found to be a greater illness burden across a range of indicators compared to later onset depression [65]. Therefore, it is possible that mental distress has to be both present in early adult life and sustained into late adulthood and early old age [66]. Another explanation may be that the increased risk observed in the younger age group is a function of the interval between exposure and dementia, as the younger participants are less likely to have died during follow-up.

Strengths and limitations

The present study has several strengths. First, it employed a linkage between a large population-based study with a high overall participation rate (92.3% for those aged 30–60 at participation) [42] and a comprehensively ascertained dementia registry in the same catchment area [47]. Also, the participation rate in HUNT1 for patients diagnosed with dementia in Nord-Trøndelag County was 86% [47], indicating that the linkage between HUNT1 and HMS can be considered valid for research purposes. Second, the linkage enabled a follow-up ranging from 11 to 27 years, decreasing the likelihood that self-reported mental distress is a marker of early stages of dementia. Third, the established dementia registry used multiple sources of information to detect and validate the dementia diagnoses, securing a high degree of certainty/reliability related to dementia diagnosis. Finally, we were able to include a range of potentially relevant confounders for the main analysis, as well as investigating the potential two-way interaction between age and gender, and mental distress on later dementia.

Some limitations are pertinent for the interpretation of the results from the present study, and should be borne in mind. First, the measure of mental distress employed in this study is not a well-validated instrument, and the psychometric properties are somewhat unclear. The range of symptoms related to mental distress that was assessed was limited, and therefore the phenomenon of mental distress as measured may be somewhat faceted and have lower specificity than validated instruments. The ADI-4, has, however, been used in several other studies and is considered as an acceptable, but crude measure of symptoms of mental distress [44,45]. Aware of this issue, we also investigated the separate items, three of which were positively associated with dementia, as well as investigating the main association using SEM-analysis with “mental distress” as a continuous latent construct. The internal consistency of the instrument was good, and an exploratory factor analysis indicated that all four items measured the same latent construct. In addition, any deficiencies in the measurement’s accuracy will have obscured rather than exaggerated associations of interest.

Second, the limited number of dementia cases decreased the precision of our estimates, restricting the ability to adjust for potential confounders in the age-stratified analyses. There were also too few cases to investigate meaningfully the impact of mid-life mental distress on different sub-types of dementia. It is, however, difficult to discern the different types of dementia conditions, and in many cases the discrimination is poor, even between Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia [38,67,68].

Third, the dementia cases which are included in the dementia registry cannot be assumed to be representative of all dementia cases residing in Nord-Trøndelag; for example, they may well be more severe [47] than the community cases not identified [69]. Also, individuals institutionalized (e.g. at mental health institutions) were not invited to participate. Although not all people suffering from dementia in Nord-Trøndelag County during the HMS study period 1995–2011 have been identified (for example those not yet diagnosed or diagnosed by other health care workers in primary care) [47], the risk estimates should only be moderately deflated, since undetected dementia cases are likely to constitute only a small fraction of the subjects considered non-cases, with misclassification unlikely to have substantial effects on observed differences in risk [47]. In addition, false positive dementia cases included in the HMS study are unlikely to have been common enough to exert an influence.

Fourth, onset of symptoms was only available for a sub-sample of the dementia cases, and was assessed in retrospect: At inclusion in the study, a next of kin was asked to report retrospectively when they noticed the first symptoms of dementia. Based on this information, the age of onset of dementia was estimated. Obviously, this information could be biased, and serves as only a crude indication for time of onset. Also, the date of diagnosis was not available, precluding any event-related analysis.

Fifth, there were few dementia cases (n = 48) among those aged under 45 years at baseline, and associations of interest in this group were thus imprecise, with wide confidence intervals. The small number of cases in the younger group also precluded any meaningful adjustment for potential confounders beyond age and gender.

Sixth, we are unable to assess and control for differential attrition, migration or mortality during follow-up, an issue which could lead to bias. There is, however, little reason to believe that these factors would lead to an inflation of the associations of interest.

Finally, there are a number of risk factors active between ascertainment of exposure and development of dementia – and these may potentially modify the association between mental distress and later dementia. The intervening risk factors could, however, reduce the likelihood of finding an association in a study with this long follow-up and controlling for subsequent factors might lead to an over-adjustment [70].

Conclusions

In summary, we found an association between midlife mental distress and risk of later dementia, which seemed to be stronger for mental distress measured in early midlife compared to late midlife. Based on the finding of the present study, in addition to those from similar studies, it is conceivable that mental distress (i.e. anxiety and depressive symptoms) is a potentially modifiable risk factor for dementia [29,68,71,72]. Although estimating the number of dementia cases which could be attributable to mental distress is beyond the scope of the present study, there are indications that adverse psychological states during the life-course impact the risk of dementia to a great extent [68]. Future research should clarify consistency of findings for established measures of mental distress and over a longer follow-up period in order to gain further knowledge about these associations.

Abbreviations

- HUNT:

-

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study

- HMS:

-

The Health and Memory Study

- ADI-4:

-

Four-item anxiety and depression measure

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- HADS-T:

-

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, total score

- DLB consortium:

-

The dementia with Lewy body consortium

- 95% CI:

-

95% Confidence interval

References

Burns A, Lliffe S. Dementia. BMJ. 2009;338:405–9.

Hofman A, Rocca WA, Brayne C, Breteler MMB, Clarke M, Cooper B, et al. The prevalence of dementia in europe: a collaborative study of 1980–1990 findings. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20(3):736–48.

Henderson AS. The coming epidemic of dementia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1983;17:117–27.

Román GC. Stroke, cognitive decline and vascular dementia: the silent epidemic of the 21st century. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:161–7.

Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–91.

WHO. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

WHO. Measuring the global burden of disease and risk factors, 1990–2001. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL, editors. Global burden of disease and risk factors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, Naghavi M, Flaxman AD, Michaud C, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990?2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–223.

Lyons D, McLoughlin DM. Recent advances: psychiatry. BMJ. 2001;323:1228–31.

Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al. Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366:2112–7.

Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Cognitive decline in prodromal alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(3):351–6.

Amieva H, Le Goff M, Millet X, Orgogozo JM, Pérès K, Barberger-Gateau P, et al. Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: successive emergence of the clinical symptoms. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(5):492–8.

Meyer JS, Xu G, Thornby J, Chowdhury MH, Quach M. Is mild cognitive impairment prodromal for vascular dementia like alzheimer’s disease? Stroke. 2002;33(8):1981–5.

van der Flier WM, Scheltens P. Epidemiology and risk factors for dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:v2–7.

McCullagh CD, Craig D, McIlroy SP, Passmore AP. Risk factors for dementia. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2001;7:24–31.

Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Salim A, O’Kearney R. Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(4):367–78.

Saunders PA, Copeland JRM, Dewey ME, Davidson IA, McWilliam C, Sharma V, et al. Heavy drinking as a risk factor for depression and dementia in elderly men: findings from the liverpool longitudinal community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:213–6.

Santibanez M, Bolumar F, Garcia AM. Occupational risk factors in Alzheimer’s disease: a review assessing the quality of published epidemiological studies. Occup Environ Med. 2007;64(11):723–32.

Gustafson D. Adiposity indices and dementia. Lancet. 2006;5:713–20.

Luchsinger JA, Gustafson DR. Adiposity and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12:15–21.

Jellinger KA. Head injury and dementia. Curr Opin Neurol. 2004;17:719–23.

Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Hall CB, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2508–16.

Wang H-X, Karp A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the kungsholmen project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(12):1081–7.

Karp A, Kåreholt I, Qiu C, Bellander T, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Relation of education and occupation-based socioeconomic status to incident of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:175–83.

Kalmijn S, Launer LJ, Ott A, Witteman JCM, Hofman A, Breteler MMB. Dietary fat intake and the risk of incident dementia in the Rotterdam study. Ann Neurol. 1997;42(5):776–82.

Nourhashemi F, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Andrieu S, Ghisolfi A, Ousset PJ, Grandjean H, et al. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71(2):643s–9.

Laurin D, Verreault R, Lindsay J, MacPherson K, Rockwood K. Physical activity and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly persons. Arch Neurol. 2001;58(3):498–504.

Mukamal KJ, Kuller LH, Fitzpatrick AL, Longstreth Jr WT, Mittleman MA, Siscovick D. Prospective study of alcohol consumption and risk of dementia in older adults. JAMA. 2003;289(11):1405–13.

Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):819–28.

Jorm AF. History of depression as a risk factor for dementia: an updated review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001;35:776–81.

Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Byers AL, McCormick M, Schaefer C, Whitmer RA. Midlife vs late-life depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: differential effects for alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(5):493–8.

Biringer E, Mykletun A, Dahl AA, David Smith A, Engedal K, Nygaard HA, et al. The association between depression, anxiety, and cognitive function in the elderly general population - the Hordaland Health Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:989–97.

Jorm AF. Is depression a risk factor for dementia or cognitive decline? A review. Gerontology. 2000;46:219–27.

Gallacher J, Bayer A, Fish M, Pickering J, Pedro S, Dunstan F, et al. Does anxiety affect risk of dementia? Findings from the Caerphilly Prospective Study. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(6):659–66.

Jacobi F, Wittchen H-U, Holting C, Hofler M, Pfister H, Muller N, et al. Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German health interview and examination survey (GHS). Psychol Med. 2004;34(4):597–612.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–27.

Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(3):316–36.

Johansson L, Guo X, Waern M, Östling S, Gustafson D, Bengtsson C, et al. Midlife psychological stress and risk of dementia: a 35-year longitudinal population study. Brain. 2010;133(8):2217–24.

Johansson L, Guo X, Hällström T, Norton MC, Waern M, Östling S, et al. Common psychosocial stressors in middle-aged women related to longstanding distress and increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a 38-year longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:1–7.

Russ TC, Hamer M, Stamatakis E, Starr JM, Batty G. Psychological distress as a risk factor for dementia death. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1859–9.

Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, Holmen TL, Midthjell K, Stene TR, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):968–77.

Holmen J, Midthjell K, Forsén L, Skjerve K, Gorseth M, Oseland A. A health survey in Nord-Trøndelag 1984–86. Participation and comparison of attendants and non-attendants. Tidsskrift for den norske Legeforening. 1990;110(15):1973–7.

Holmen J, Midthjell K, Krüger O, Langhammer A, Holmen TL, Bratberg GH, et al. The nord-trøndelag health study 1995–97 (HUNT 2): objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2003;13(1):19–32.

Bjerkeset O, Romundstad P, Evans J, Gunnell D. Association of adult body mass index and height with anxiety, depression, and suicide in the general population: the hunt study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(2):193–202.

Bjerkeset O, Nordahl HM, Mykletun A, Holmen J, Dahl AA. Anxiety and depression following myocardial infarction: gender differences in a 5-year prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(2):153–61.

Cosco TD, Doyle F, Ward M, McGee H. Latent structure of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: a 10-year systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(3):180–4.

Bergh S, Holmen J, Gabin J, Stordal E, Fikseaunet A, Selbaek G, et al. Cohort profile: the Health and Memory Study (HMS): a dementia cohort linked to the HUNT study in Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(6):1759–68.

WHO. ICD-10. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005.

McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, Perry EK, Dickson DW, Hansen LA, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB): report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology. 1996;47(5):1113–24.

Neary D, Snowden JS, Mann DM. Classification and description of frontotemporal dementias. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;920:46–51.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2011.

Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2004.

Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4):351–7.

Lemere CA, Blusztajn JK, Yamaguchi H, Wisniewski T, Saido TC, Selkoe DJ. Sequence of deposition of heterogeneous amyloid β-peptides and apo e in down syndrome: implications for initial events in amyloid plaque formation. Neurobiol Dis. 1996;3(1):16–32.

Wilson RS, Evans DA, Bienias JL, de Leon CF M, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Proneness to psychological distress is associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 2003;61(11):1479–85.

Alexopoulus GS, Bruce ML, Silbersweig D, Kalayan B, Stern E. Vascular depression: a new view of late-onset depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 1999;1(2):68–80.

Alexopoulos GS. The vascular depression hypothesis: 10 Years Later. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60(12):1304–5.

Westerlund H, Gustafsson PE, Theorell T, Janlert U, Hammarström A. Social adversity in adolescence increases the physiological vulnerability to Job strain in adulthood: a prospective population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e35967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035967 (pp. 1-8).

Fratiglioni L, Launer LJ, Andersen K, Breteler MM, Copeland JR, Dartigues JF, et al. Incidence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group. Neurology. 2000;54(11 Suppl 5):S10–5.

Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530–8.

Hynd MR, Scott HL, Dodd PR. Glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem Int. 2004;45(5):583–95.

Lara VP, Caramelli P, Teixeira AL, Barbosa MT, Carmona KC, Carvalho MG, et al. High cortisol levels are associated with cognitive impairment no-dementia (CIND) and dementia. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;423:18–22.

van der Flier WM, Pijnenburg YAL, Fox NC, Scheltens P. Early-onset versus late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: the case of the missing APOE ɛ4 allele. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(3):280–8.

Koedam ELGE, Lauffer V, van der Vlies AE, van der Flier WM, Scheltens P, Pijnenburg YAL. Early-versus late-onset alzheimer’s disease: more than age alone. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19(4):1401–8.

Zisook S, Lesser I, Stewart JW, Wisniewski SR, Balasubramani GK, Fava M, et al. Effect of age at onset on the course of major depressive disorder. A J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1539–46.

McEwen BS. Allostasis and allostatic load: implications for neuropsychopharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22(2):108–24.

Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of alzheimer disease: the nun study. JAMA. 1997;277(10):813–7.

Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(5):329–35.

Sampson EL, Blanchard MR, Jones L, Tookman A, King M. Dementia in the acute hospital: prospective cohort study of prevalence and mortality. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(1):61–6.

Johansson L, Guo X, Hällström T, Norton MC, Waern M, Östling S, et al. Common psychosocial stressors in middle-aged women related to longstanding distress and increased risk of Alzheimer's disease: a 38-year longitudinal population study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:9 e003142. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003142 (pp. 1-7).

Cuijpers P, Van Straten A, Smit F. Preventing the incidence of new cases of mental disorders: a meta-analytic review. J NervMentDis. 2005;193(2):119–25.

Cuijpers P, Beekman ATF, Reynolds CF. Preventing depression: a global priority. JAMA. 2012;307(10):1033–4.

Acknowledgements

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (The HUNT Study) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

No specific funding was received for this research. Robert Stewart is part-funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre and Dementia Biomedical Research Unit at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JCS and OB were responsible for the conception of this study, and the study design was further developed by JCS, OB and SB. Analyses were carried out by JCS, and manuscript preparation was led by JCS in cooperation with OB, SB, RS and AKK. JCS, SB, RS, AKK and OB were all involved in the interpretation of the data, drafting of the article and approval of the final manuscript. OB is the guarantor for the study.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Comparison between those with valid responses on ADI-4 (75.7%) versus those with one or more missing components of ADI-4 (24.3%). N=40,803. Figure S1. Predicted estimated probability of dementia across ADI-4 percentiles (N=30,902).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Skogen, J.C., Bergh, S., Stewart, R. et al. Midlife mental distress and risk for dementia up to 27 years later: the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) in linkage with a dementia registry in Norway. BMC Geriatr 15, 23 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0020-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0020-5