Abstract

Background

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic progressive liver disease leading to biliary fibrosis and cirrhosis. Cilofexor is a nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor agonist that demonstrated significant improvements in liver biochemistry and markers of cholestasis in patients with PSC in a phase 2 study. We describe here the rationale, design, and implementation of the phase 3 PRIMIS trial, the largest placebo-controlled trial in PSC.

Methods

Adults with large-duct PSC without cirrhosis are randomized 2:1 to receive oral cilofexor 100 mg once daily or placebo for up to 96 weeks during the blinded phase. Patients completing the blinded phase are eligible to receive open-label cilofexor 100 mg daily for up to 96 weeks. The primary objective is to evaluate whether cilofexor reduces the risk of fibrosis progression compared with placebo. Liver biopsy is performed at screening and Week 96 of the blinded phase for histologic assessment of fibrosis. The primary endpoint—chosen in conjunction with guidance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration—is the proportion of patients with ≥ 1-stage increase in fibrosis according to Ludwig histologic classification at week 96. Secondary objectives include evaluation of changes in liver biochemistry, serum bile acids, liver fibrosis assessed by noninvasive methods, health-related quality of life, and safety of cilofexor.

Conclusion

The phase 3 PRIMIS study is the largest randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in PSC to date and will allow for robust evaluation of the efficacy and safety of cilofexor in noncirrhotic patients with large-duct PSC.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03890120; registered 26/03/2019.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a chronic and progressive cholestatic liver disease of unknown etiology characterized by persistent inflammation, stricturing, and obliterative fibrosis of the bile ducts, ultimately resulting in biliary cirrhosis [1,2,3]. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is an orphan disease with an estimated mean global prevalence of 10 per 100,000 population with ~ 30,000 individuals in the United States [4]. More than half of patients with PSC are men; affected individuals are generally diagnosed at ages 30–40 years, although pediatric and older ages at presentation also occur. Concomitant inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), most typically ulcerative colitis, occurs in the majority of patients [1, 5,6,7]. PSC is typically classified based on the location of biliary injury (small ducts, large ducts, or both) and the presence of underlying IBD. Patients with small-duct PSC have a more indolent course than those with classic large-duct PSC [6,7,8]. Although often asymptomatic in the early stages, as PSC progresses, patients can present with symptoms such as fatigue, abdominal pain, and pruritus, in addition to symptoms attributable to underlying IBD [7, 9,10,11,12]. With progression, potentially devastating complications such as dominant biliary strictures, recurring ascending cholangitis, and hepatic decompensation (eg, ascites, variceal hemorrhage, and hepatic encephalopathy [HE]) can occur [6,7,8]. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is also associated with metabolic bone disease and an increased risk of multiple malignancies, particularly cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, and colorectal neoplasia [13, 14].

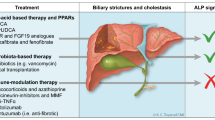

The clinical management of PSC is challenging. While multiple drugs have been evaluated including immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and antifibrotics, no pharmacologic therapy has been proven to improve clinical outcomes [3, 6, 7, 15]. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a hydrophilic bile acid, improves liver biochemistry in most patients with PSC, but has not been shown to improve clinical outcomes, with high doses potentially harmful [7, 16, 17]. Liver transplantation is the only life-extending therapeutic option currently available, but the disease recurs in ~ 25% of patients at 5 years posttransplant [7, 18, 19]. The lack of effective treatment options, the clinical burden of PSC, and the variable, progressive nature of the disease have a substantial negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and well-being, resulting in feelings of depression, anxiety, helplessness, and social isolation [12, 20,21,22].

A key pathophysiologic feature of PSC is dysregulation of bile acid homeostasis, characterized by altered bile acid composition and cholestasis [23, 24]. The farnesoid X receptor (FXR), a ligand-activated nuclear hormone receptor highly expressed in the liver, gallbladder, intestines, and kidney, is a key regulator of bile acid homeostasis [16, 25,26,27]. Activation of FXR by naturally occurring bile acids or synthetic FXR agonists, both within the intestine and hepatocytes, suppresses bile acid synthesis, inhibits bile acid uptake by hepatocytes, and promotes bile acid excretion, all of which lead to reduction of bile acid accumulation in the liver and enterohepatic circulation [16, 25, 26]. Farnesoid X receptor agonism also has anti-inflammatory effects, and may improve gut barrier function and reduce portal hypertension [16]. Activation of FXR, therefore, has pleiotropic effects that may be beneficial in cholestatic disorders such as PSC.

Cilofexor (formerly GS-9674) is a potent and selective nonsteroidal FXR agonist [27]. In preclinical models of liver fibrosis, cilofexor demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects, reducing hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension [28, 29]. To potentially improve tolerability and safety, cilofexor was designed and is dosed to predominantly activate intestinal FXR. This property is distinct from first-generation, bile acid–derived FXR agonists, such as obeticholic acid, which have greater effects on hepatic FXR and enterohepatic circulation [16, 27]. In a phase 2 study of 52 adults with large-duct PSC without cirrhosis, cilofexor 100 mg daily was well tolerated and had no adverse impact on IBD symptoms. Compared with placebo, cilofexor 100 mg significantly improved liver biochemistry, including serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and reduced serum bile acids and serum C4 levels, a bile acid precursor. Cilofexor also demonstrated potential antifibrotic effects by reducing serum levels of the profibrogenic protein tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 [27].

Based on the results from the phase 2 study, the efficacy and safety of cilofexor is now under evaluation in the PRIMIS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03890120, registered 26/03/2019). This manuscript describes the design and rationale for the largest, multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study in patients with PSC to date.

Methods

Patients

Adult patients aged 18–75 years with a diagnosis of classic, large-duct PSC based on cholangiographic imaging (magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography [MRCP], endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, or percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram) are eligible for the study. Small duct PSC and other causes of liver disease including immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4)–related sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis/PSC overlap syndrome, and secondary sclerosing cholangitis are excluded. All patients have a liver biopsy at screening (or historical liver biopsy within 6 months of screening) that is deemed acceptable for interpretation by a central pathologist (Z.D.G.) and demonstrates stage F0–F3 fibrosis according to Ludwig classification [30]. Patients with clinical (eg, prior evidence of hepatic decompensation, platelet count < 150,000/mm3, and liver stiffness by vibration-controlled transient elastography [VCTE; FibroScan®, Echosens, Paris, France] > 20.0 kPa) and/or histologic evidence of cirrhosis are excluded from the study, because at the time of study initiation, the pharmacokinetics (PK) and tolerability of cilofexor in patients with cirrhosis were unclear. Patients are eligible regardless of baseline serum ALP concentration and use of UDCA, which must be stable for ≥ 6 months before screening. In patients with history of IBD, doses of biologic treatments, immunosuppressants, or systemic corticosteroids must be stable for ≥ 3 months prior to screening. Moderate to severe IBD—defined as a partial Mayo score > 4 and/or a score in the screening visit rectal bleeding domain > 1 (unless bleeding is due to perianal disease)—is exclusionary. Additional key inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1.

Study design

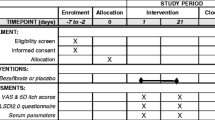

This phase 3 study consists of 2 phases: a blinded phase and an open-label extension (OLE) phase (Fig. 1). The blinded phase includes a 10-week screening period, 96 weeks of treatment, and a follow-up visit 4 weeks after completion of Week 96 or early termination (ET). Owing to the rarity and high unmet need of PSC, and the requirement for placebo treatment of nearly 2 years in some patients, eligible patients are randomized unevenly in a 2:1 ratio to receive active treatment with oral cilofexor 100 mg or placebo daily. Randomization is stratified by presence or absence of UDCA use and bridging fibrosis (Ludwig fibrosis stage F3 vs. F0–F2) on screening liver biopsy, the latter reflecting an important prognostic factor in this population [15]. After screening, in-clinic study visits occur at baseline, Weeks 4, 8, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, and 96 or ET, and the follow-up visit. This 96-week blinded phase will provide evidence for the safety and efficacy of cilofexor vs placebo in different patient subgroups at risk for progressive hepatic fibrosis and the development of cirrhosis.

Patients who do not permanently discontinue study drug and complete the blinded phase Week 96 or follow-up visit are eligible to enter the OLE phase, and receive open-label cilofexor 100 mg daily for up to 96 weeks. The OLE phase includes a 4-week rollover period, 96 weeks of treatment, and a follow-up visit 4 weeks after completion of OLE Week 96 or ET. After rollover, in-clinic study visits occur at OLE baseline, Weeks 4, 24, 48, 72, and 96 or ET, and the follow-up visit. This 96-week OLE phase will provide additional data regarding the long-term safety and efficacy of cilofexor.

The study was initiated in March 2019 with an initial focus on activation of North American study sites. In autumn 2019, changes to the protocol were made with an amendment based on patient and investigator requests to decrease study burden and reduce recruitment delays. These changes included increasing the upper age cutoff from 70 to 75 years, extension of the screening window from 8 to 10 weeks, addition of a 14-day visit window for the initial MRCP, and an optional liver stiffness measurement by VCTE. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and requests by sites and potential subjects to facilitate enrollment, an additional amendment was initiated in the spring of 2020 that included reductions in the numbers of on-site study visits, collections of samples for biomarkers, and PSC-related HRQOL questionnaires. A fourth amendment in June 2021 added an interim futility analysis based on the primary endpoint after the first 160 randomized and dosed patients completed the blinded phase of the study and the OLE phase, based on requests of patients and investigators.

Dosing rationale

The oral 100 mg daily dosage of cilofexor was selected for the phase 3 study based on safety, efficacy, and PK and pharmacodynamic data from the dose-ranging phase 2 PSC study [27], data from a phase 2 study in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [31], and phase 1 studies in healthy subjects [32, 33]. In the phase 2 PSC study, improvements in liver biochemistry, including serum ALP, ALT, AST, and GGT, and serum bile acids after 12 weeks of treatment with cilofexor were greater with the 100 versus 30 mg dose, while the incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), including Grade 2 or 3 pruritus, was mostly similar between the two doses [27]. In the phase 1 studies, cilofexor exhibited less than dose-proportional increases in systemic exposure at doses > 100 mg [32, 33], suggesting that higher doses may provide only marginal incremental benefits in efficacy, with a higher potential risk of AEs including pruritus. The combined safety, efficacy, and PK data supported evaluation of cilofexor 100 mg daily in patients with PSC in the present phase 3 study.

Study objectives and endpoint rationale

Because of the heterogeneity and slow progression of PSC, Level-1 clinical endpoints measuring outcomes of death, liver transplantation, and cholangiocarcinoma are challenging due to the low incidence of clinical events in phase 2 and 3 studies of typical size and duration [34, 35]. To overcome this challenge, the International PSC Study Group (IPSCSG) has proposed several biomarkers as surrogate endpoints, including serum ALP, a well-established biomarker of cholestasis [36]. For a biomarker to be accepted as a surrogate endpoint, it must be “reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit” [35, 36]. Although ALP is a useful and appropriate endpoint for small, short-term, phase 2 studies, recent pooled data from the simtuzumab phase 2 PSC trial demonstrated large inter- and intraindividual variations in ALP activity and a lack of association between changes in ALP alone with disease progression [37]. Currently, none of the potential endpoints proposed by IPSCSG is approved by global regulatory authorities for use as a surrogate to support accelerated approval of experimental drugs in PSC [35, 36].

The primary objective of the PRIMIS trial is to evaluate whether cilofexor reduces the risk of fibrosis progression among noncirrhotic patients with large-duct PSC. As such, the primary endpoint is the proportion of patients with liver fibrosis progression, defined as ≥ 1-stage increase in fibrosis according to Ludwig classification (stage 1, cholangitis/portal hepatitis; stage 2, periportal fibrosis; stage 3, septal fibrosis or bridging necrosis; stage 4, biliary cirrhosis) from baseline to Week 96. The Ludwig staging system has previously shown strong associations with the occurrence of liver-related events (eg, ascites, HE, and transplantation), including in an international cohort study [35, 38]. In the simtuzumab study, no worsening of fibrosis was associated with a significantly reduced risk of clinical events at Weeks 48 and 96 among noncirrhotic patients with PSC (Fig. 2) [15]. In addition, higher levels of fibrosis content at baseline, based on either traditional Ludwig staging or a continuous score, such as hepatic collagen by morphometry, were associated with clinical events (Fig. 3). Based on this prognostic relevance, a histology-based endpoint is considered by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to be an acceptable surrogate endpoint in PRIMIS to support the accelerated approval of cilofexor for the treatment of PSC. While draft guidance from the European Medicines Agency has recommended use of the Nakanuma staging system [38], this system has similar reproducibility and prognostic value to Ludwig classification, despite the inclusion of more histologic parameters and requirement for orcein staining, which is not routinely performed.

Greater fibrosis burden at baseline, as defined by Ludwig fibrosis stage or hepatic collagen content by morphometry, was associated with a significantly increased risk of disease progression among noncirrhotic patients with PSC in the phase 2 simtuzumab study. Disease progression was defined by progression to cirrhosis (F4), ascending cholangitis, hepatic decompensation, liver transplantation, or death. [15] p values by log-rank test

The ultimate goal for any therapy in PSC is to prevent liver-related complications. While the PRIMIS trial is underpowered to demonstrate a benefit of cilofexor on clinical events, data on relevant complications are being prospectively recorded and adjudicated in a blinded fashion according to standardized criteria by a committee of experts. Specifically, a composite of clinical events that constitute this clinical efficacy endpoint have been defined and include: (1) progression to cirrhosis (liver biopsy showing F4 fibrosis according to Ludwig classification in the opinion of the central reader or clinical evidence of cirrhosis); (2) events of hepatic decompensation (clinically apparent ascites, Grade ≥ 2 HE by West Haven criteria requiring treatment, and portal hypertension-related upper gastrointestinal bleeding identified by endoscopy and requiring hospitalization); (3) liver transplantation or qualification for liver transplantation (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease [MELD] score ≥ 15 on ≥ 2 consecutive occasions ≥ 4 weeks apart); and (4) all-cause mortality. The hepatic events adjudication committee will also review all cases of cholangiocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, ascending cholangitis, and dominant strictures as events of special interest.

The secondary objectives of the PRIMIS trial include assessment of the safety and tolerability of cilofexor, and evaluation of changes in liver biochemistry, serum bile acids, liver fibrosis assessed by histology (specifically fibrosis improvement) and noninvasive methods (eg, Enhanced Liver Fibrosis [ELF™] score [Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany], and liver stiffness by VCTE), and HRQOL. Biochemical responses and noninvasive markers of fibrosis may support the beneficial effects of cilofexor on disease progression to supplement the primary histologic endpoint and prove useful for prognostication and disease monitoring in the future. Indeed, baseline levels and changes in these fibrosis markers were associated with risk of disease progression among patients in the simtuzumab trial [15]. A key secondary endpoint to be evaluated in PRIMIS is the proportion of patients with ≥ 25% relative reduction in serum ALP concentration from baseline (biochemical response) and no worsening of fibrosis according to Ludwig classification (histologic response) at Week 96. This endpoint is consistent with draft guidance from the European Medicines Agency and recommendations from IPSCSG.

Among a variety of HRQOL measures to be collected in the PRIMIS trial is the disease-specific PSC-patient-reported outcome (PSC-PRO) instrument, which was developed according to FDA guidelines to complement clinical outcomes data. In a preliminary validation of PSC-PRO in patients with PSC [12], it demonstrated excellent internal consistency, discriminant validity, and test–retest reliability, and specific domains within the instrument were well correlated with relevant domains of other HRQOL instruments including the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire, and PBC-40. Importantly, PSC-PRO could differentiate patients with PSC according to presence and severity of cirrhosis. The primary, secondary, and exploratory endpoints of PRIMIS are listed in Table 2.

Study assessments

Liver biopsy for histologic staging of fibrosis is performed at screening and Week 96 during the blinded phase and reviewed by the central reader. Biopsies are performed under ultrasound guidance, when possible, to reduce the risk of AEs. Measurements of serum markers of liver injury and function, including ALP, GGT, ALT, AST, bilirubin, albumin, and INR, and clinical liver assessments, including ascites, HE, and calculation of MELD and Child–Pugh scores, are performed at screening and all in-clinic study visits during the blinded and OLE phases. Serum bile acids, noninvasive markers of fibrosis, and health resource utilization and HRQOL questionnaires are evaluated at specified time points (Table 3). Imaging of biliary and pancreatic ducts by MRCP is performed at baseline, and Weeks 48 and 96 or ET during the blinded phase, read locally for any clinically significant abnormalities to ensure patient safety, and reviewed by a central reader (C.T.A.) to evaluate changes to the biliary tree according to standardized criteria [39].

Safety is assessed through the reporting of AEs, clinical laboratory tests including lipid profiles, and vital sign assessments at various time points throughout the study; concomitant medication usage is also assessed (Table 3). An independent, external Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) comprising 2 hepatologists and a PhD statistician convenes after 50 patients have completed the Week 4 visit, and approximately every 6 months thereafter during the blinded and OLE phases to monitor the study for safety events. To mitigate the potential risk of liver injury, patients are monitored closely with defined rules for study drug withholding due to elevated liver tests; all potential cases of drug hepatotoxicity are adjudicated by an independent drug-induced liver injury adjudication committee. For patients with new or worsening pruritus, management strategies include nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions (eg, topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and bile acid sequestrants), and treatment interruption or dose reduction of cilofexor (to 30 mg daily) in cases of intolerable pruritus. At the time of writing of this manuscript, there have been four independent DSMB assessments of the data with the conclusion that the study should proceed without change to the protocol.

Statistical analyses

Considerable efforts were undertaken to balance the needs for a statistically rigorous study while limiting the exposure of patients with PSC to long-term treatment with placebo. As such, eligible patients were randomized 2:1 to receive cilofexor (n = 267) or placebo (n = 133). This sample size of 400 patients in total was calculated to have > 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 15% in the percentages of patients who meet the primary histologic endpoint at blinded study phase Week 96. The power analysis was conducted using Pearson’s chi-square test at a 2-sided significance level of 0.05. This calculation assumed that 25% of patients would discontinue the study prematurely (considered as treatment failures) and that among those with nonmissing response data at blinded phase Week 96, 20% in the cilofexor arm and 40% in the placebo arm would meet the primary endpoint. The 40% estimate of fibrosis progression in the placebo arm is based on Week 96 data from patients without cirrhosis in the simtuzumab trial [15].

The PRIMIS trial contains 3 planned analyses. First, an interim futility analysis based on the primary histologic endpoint will be conducted after the first 160 randomized and dosed patients have completed Week 96 or ET assessments in the blinded phase. A predictive power approach, which calculates the probability of observing a statistically significant result for the primary endpoint given the interim data, will be used for this assessment. Specifically, the data monitoring committee may recommend early termination of the study due to futility if the predictive power is ≤ 10%. Second, the primary analyses on the primary, secondary, and exploratory endpoints will be conducted after all randomized and dosed patients have completed Week 96 or ET assessments in the blinded phase. The final analyses will be performed after all patients have completed the OLE phase follow-up visit.

For the primary analysis, a stratified Mantel–Haenszel test will be used to compare the difference in proportions of patients with liver fibrosis progression at blinded phase Week 96 (primary endpoint) between cilofexor and placebo at a 1-sided significance level of 0.025, adjusting for baseline UDCA use and fibrosis stage (Ludwig fibrosis score F3 vs. F0–F2) on screening liver biopsy. Patients with missing data on liver fibrosis or with clinical events occurring prior to Week 96 will be analyzed as treatment failures. Secondary efficacy endpoints will be tested sequentially in a prespecified order after the primary endpoint has been met. If a 1-sided p value ≤ 0.025 is achieved for one endpoint, the next endpoint will be evaluated; otherwise, testing of the remaining endpoints will cease. For these analyses, an analysis of covariance model will be used for continuous and ordinal outcomes, and a stratified Mantel–Haenszel test will be used for binary outcomes, adjusting for baseline stratification factors. Exploratory endpoints and safety will be summarized using descriptive methods by treatment group.

Discussion

The PRIMIS trial is the largest multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study in PSC to date. Screening for the study initiated in March 2019, and by December 2020, 204 sites in 16 countries in Australasia, Europe, Japan, and North America have been activated. An additional site was later activated. In all, 419 noncirrhotic patients with large-duct PSC have been enrolled and 416 were dosed. The screen failure rate was 29% (171/590 patients screened), with major reasons for screen failure including laboratory abnormalities, current or recent history of PSC-related complications, and noneligible screening liver biopsy, each occurring in > 10% of screen-failed subjects. Among patients who were dosed and have available baseline data as of February 14, 2022, median age is 44 years (range 18–74), 62% are men, 70% have history of IBD, 59% are on UDCA, and 25% have F3 fibrosis on screening liver biopsy. Median serum ALP concentration is 173 U/L (interquartile range 107, 292), with 69% of enrolled patients having elevated serum ALP.

The primary endpoint of the PRIMIS trial will provide clinically relevant information on whether cilofexor can reduce progression of liver fibrosis in noncirrhotic patients with large-duct PSC. Currently, no approved pharmacologic treatment for PSC exists, in part, due to lack of clarity regarding which endpoints may reliably serve as surrogates of clinical outcomes in PSC. The rarity of PSC and its generally prolonged natural history pose inherent difficulties in performing adequately powered, clinical outcomes studies [35, 36]. For example, in a large population-based study from the Netherlands, Boonstra and colleagues [5] reported an estimated median survival from diagnosis to transplant or PSC-related death of 21 years. In a large, 5-year trial of high-dose UDCA, the incidence of clinical events including liver transplantation and death was ~ 3% annually in patients receiving placebo [40]. As patients with cirrhosis are excluded from PRIMIS, a lower rate of clinical events would be expected in this trial. Considering these challenges, fibrosis progression on liver biopsy was chosen, in close collaboration with the FDA, as the primary endpoint of PRIMIS and endorsed by the FDA as acceptable for accelerated approval of cilofexor assuming success of the phase 3 study. Data on progression to cirrhosis—defined histologically or clinically, adjudicated centrally, and expected to occur primarily in patients with bridging (F3) fibrosis at baseline (25% of patients in PRIMIS)—will contribute to the evidence regarding the efficacy of cilofexor.

The strengths and limitations of the study reflect the inherent challenge of conducting a study in a chronic disease indication such as PSC with variable clinical course. Regulatory support of the histologic endpoints to be evaluated in the PRIMIS trial is based on the well-accepted observation that severity of liver fibrosis correlates with risk of clinical events in PSC, as well as other liver diseases [15]. A major shortcoming of liver histology in PSC is sampling variability due to the patchy distribution of injury and fibrosis. Dominant strictures may affect only one hepatic lobe or segment, which may be missed by random sampling of liver tissue (typically percutaneously from the right lobe) and the inability to obtain serial biopsies from the same location. The invasive nature and potential complications of liver biopsy are additional limitations. For this reason, the clinical practice guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and European Association for the Study of the Liver do not currently recommend liver biopsy in the routine management of PSC, except to rule out other diagnoses or diagnose small-duct PSC [2, 41]. A requirement for serial liver biopsies may also impede patient recruitment in trials of novel therapies for PSC. However, this was not a major obstacle to enrollment in PRIMIS, confirming findings from the simtuzumab study, which required three liver biopsies per patient over 96 weeks. Thus, the inherent limitations of a biopsy-based primary endpoint in PRIMIS were governed by the need to conduct a regulatory-defined endpoint within a reasonable time frame.

The phase 2 study of cilofexor in noncirrhotic patients with PSC demonstrated that cilofexor significantly improved markers of cholestasis, liver biochemistry, and bile acid homeostasis [27]. Several key secondary endpoints in the PRIMIS trial include changes in liver biochemistry and noninvasive markers of fibrosis, such as liver stiffness by VCTE and ELF score. These markers were significantly associated with PSC-related complications in multiple prior studies [15, 42, 43]. For example, in the simtuzumab study among patients without cirrhosis, those with baseline liver stiffness by VCTE ≥ 8.2 kPa had an ~ sevenfold risk of disease progression. After adjusting for baseline values, an increase of 1 kPa during follow-up was associated with an 8% increase in risk of events (hazard ratio [HR] per 1 kPa: 1.08; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.03, 1.13). Similarly, greater ELF score at baseline (HR per 0.5 units: 1.34; 95% CI 1.21, 1.49) and greater increases over time (HR per 0.5 units: 1.36; 95% CI 1.17, 1.59) were associated with higher likelihood of disease progression. Data in the larger population of PRIMIS will inform whether cilofexor improves these markers over the longer term and supplement data obtained from liver histology regarding the putative antifibrotic effects of this therapy. Moreover, the systematic, protocol-based evaluation of liver fibrosis based on histology and noninvasive markers at baseline and over time will provide valuable information regarding the natural history of noncirrhotic large-duct PSC, and help confirm the utility of these surrogate markers for risk stratification and disease monitoring.

The long-term safety profile of cilofexor in PSC has been evaluated in the 96-week OLE of the phase 2 study and will be further evaluated in the PRIMIS trial. Available data from the phase 1 and 2 studies in healthy subjects, and patients with PSC and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis indicate that cilofexor was generally well tolerated [27, 31,32,33, 44]. Pruritus, a symptom commonly associated with cholestatic liver diseases [7, 9,10,11] and a known complication of FXR agonist therapy [17], was lower in patients treated with cilofexor vs placebo during the 12-week double-blind period of the phase 2 PSC study. Premature discontinuation of therapy was observed in 1 patient (2%) treated with cilofexor during the double-blind phase [27] and in 5 (11%) during the OLE phase of that study. Given the important impact of pruritus on HRQOL in patients with PSC, a protocol-defined pruritus management plan was implemented in PRIMIS to potentially mitigate the risk of treatment discontinuations due to this symptom. This plan includes temporary interruption of study drug dosing, a dose-escalation scheme at defined study intervals (beginning at cilofexor 30 mg or placebo), and supportive management with antipruritic medications.

Conclusion

The PRIMIS trial is a pivotal phase 3 study designed to evaluate the long-term effects of cilofexor on fibrosis progression, liver biochemistry, and HRQOL, as well as PSC-related complications, over a 192-week treatment period in noncirrhotic patients with large-duct PSC. This study will provide valuable data on the natural history of PSC, with histologic and serologic assessments in patients receiving placebo over the 96-week blinded phase. This largest randomized controlled PSC study will allow for robust investigation of the long-term therapeutic efficacy and safety of cilofexor and should provide critical insights on the disease state and natural progression of noncirrhotic large-duct PSC.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available because the study described is currently in-progress. Once the study is completed, the data are available from the study sponsor on reasonable request. Data requests should be sent to datarequest@gilead.com.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- CLDQ:

-

Chronic liver disease questionnaire

- C–P:

-

Child–Pugh

- ELF:

-

Enhanced liver fibrosis

- ET:

-

Early termination

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FXR:

-

Farnesoid X receptor

- GGT:

-

γ-Glutamyl transferase

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- HE:

-

Hepatic encephalopathy

- HRQOL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IgG4:

-

Immunoglobulin G4

- INR:

-

International normalized ratio

- IPSCSG:

-

International PSC Study Group

- MELD:

-

Model for end-stage liver disease

- MRCP:

-

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

- PK:

-

Pharmacokinetics

- PSC:

-

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- PSC-PRO:

-

Primary sclerosing cholangitis-patient-reported outcome

- OLE:

-

Open-label extension

- SIBDQ:

-

Short inflammatory bowel disease queistionnaire

- UDCA:

-

Ursodeoxycholic acid

- VCTE:

-

Vibration-controlled transient elastography

References

Chapman MH, Thorburn D, Hirschfield GM, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology and UK-PSC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut. 2019;68:1356–78.

Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, et al. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:660–78.

Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, Adams DH. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382:1587–99.

Trivedi PJ, Bowlus CL, Yimam KK, et al. Epidemiology, natural history, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a systematic review of population-based studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;S1542–3565(21):00919–28.

Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1181–8.

Chapman RW. Update on primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Liver Dis. 2017;9:107–10.

Lazaridis KN, LaRusso NF. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1161–70.

Takakura WR, Tabibian JH, Bowlus CL. The evolution of natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:71–7.

Karlsen TH, Folseraas T, Thorburn D, Vesterhus M. Primary sclerosing cholangitis–a comprehensive review. J Hepatol. 2017;67:1298–323.

Kuo A, Gomel R, Safer R, et al. Characteristics and outcomes reported by patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis through an online registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1372–8.

Walmsley M, Langford A, Thorburn D, et al. Clinical need in PSC and clinically meaningful change: what is important to patients? March 3, 2016. Available at: https://www.pscsupport.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/PSC-Support-Patient-Survey-Results.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2021.

Younossi ZM, Afendy A, Stepanova M, et al. Development and validation of a primary sclerosing cholangitis-specific patient-reported outcomes instrument: the PSC PRO. Hepatology. 2018;68:155–65.

Fung BM, Lindor KD, Tabibian JH. Cancer risk in primary sclerosing cholangitis: epidemiology, prevention, and surveillance strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:659–71.

Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, part 2: cancer risk, prevention, and surveillance. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:427–32.

Muir AJ, Levy C, Janssen HLA, et al. Simtuzumab for primary sclerosing cholangitis: phase 2 study results with insights on the natural history of the disease. Hepatology. 2019;69:684–98.

Krones E, Marschall H-U, Fickert P. Future medical treatment of PSC. Curr Hepatology Rep. 2019;18:96–106.

Tabibian JH, Ali AH, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, part 1: epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, clinical features, and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14:293–304.

Henson JB, Patel YA, King LY, et al. Outcomes of liver retransplantation in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:769–80.

Steenstraten IC, Sebib Korkmaz K, Trivedi PJ, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: risk factors for recurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis after liver transplantation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:636–43.

Arndtz K, Hirschfield GM. Quality of life and primary sclerosing cholangitis: the business of defining what counts. Hepatology. 2018;68:16–8.

Ranieri V, McKay K, Walmsley M, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and psychological wellbeing: a scoping review. Semin Liver Dis. 2019;39:104–10.

Walmsley M, Leburgue A, Thorburn D, et al. Identifying research priorities in primary sclerosing cholangitis: driving clinically meaningful change from the patients’ perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;70:e412–3.

Tabibian JH, Bowlus CL. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: a review and update. Liver Res. 2017;1:221–30.

Vesterhus M, Karlsen TH. Emerging therapies in primary sclerosing cholangitis: pathophysiological basis and clinical opportunities. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:588–614.

Chiang JY. Bile acids: regulation of synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1955–66.

Chiang JY, Kimmel R, Weinberger C, Stroup D. Farnesoid X receptor responds to bile acids and represses cholesterol 7alpha-hydroxylase gene (CYP7A1) transcription. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10918–24.

Trauner M, Gulamhusein A, Hameed B, et al. The nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor agonist cilofexor (GS-9674) improves markers of cholestasis and liver injury in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2019;70:788–801.

Schwabl P, Hambruch E, Budas GR, et al. The non-steroidal FXR agonist cilofexor improves portal hypertension and reduces hepatic fibrosis in a rat NASH model. Biomedicines. 2021;9:60.

Sroda N, Fuchs CD, Suriben R, et al. Cilofexor reduces fibrosis and improves measures of liver function in the Mdr2 knockout mouse model of biliary fibrosis. Presented at The Liver Meeting® (AASLD), 2021; poster 1254.

Ludwig J, Dickson ER, McDonald GS. Staging of chronic nonsuppurative destructive cholangitis (syndrome of primary biliary cirrhosis). Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1978;379:103–12.

Patel K, Harrison SA, Elkhashab M, et al. Cilofexor, a nonsteroidal FXR agonist, in patients with non-cirrhotic NASH: a phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2020;72:58–71.

Djedjos CS, Kirby BJ, Billin A, et al. Pharmacodynamic effects of the oral, nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor agonist GS-9674 in healthy volunteers [abstract]. Hepatology. 2016;63(Suppl 1):543A.

Kirby BJ, Djedjos CS, Birkeback J, et al. Evaluation of the safety and pharmacokinetics of the oral, nonsteroidal farnesoid x receptor agonist GS-9674 in healthy volunteers. Presented at The Liver Meeting (AASLD); 2016; Boston, MA; poster 1140.

Fleming TR. Surrogate endpoints and FDA’s accelerated approval process. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24:67–78.

Ponsioen CY. Endpoints in the design of clinical trials for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864:1410–4.

Ponsioen CY, Chapman RW, Chazouillères O, et al. Surrogate endpoints for clinical trials in primary sclerosing cholangitis: review and results from an International PSC Study Group consensus process. Hepatology. 2016;63:1357–67.

Trivedi PJ, Muir AJ, Levy C, et al. Inter- and intra-individual variation, and limited prognostic utility, of serum alkaline phosphatase in a trial of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1248–57.

de Vries EMG, de Krijger M, Färkkilä M, et al. Validation of the prognostic value of histologic scoring systems in primary sclerosing cholangitis: an international cohort study. Hepatology. 2017;65:907–19.

Ruiz A, Lemoinne S, Carrat F, et al. Radiologic course of primary sclerosing cholangitis: assessment by three-dimensional magnetic resonance cholangiography and predictive features of progression. Hepatology. 2014;59:242–50.

Olsson R, Boberg KM, de Muckadell OS, et al. High-dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis: a 5-year multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1464–72.

European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237–67.

Corpechot C, Gaouar F, El Naggar A, et al. Baseline values and changes in liver stiffness measured by transient elastography are associated with severity of fibrosis and outcomes of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:970–9.

Vesterhus M, Hov JR, Holm A, et al. Enhanced liver fibrosis score predicts transplant-free survival in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2015;62:188–97.

Loomba R, Noureddin M, Kowdley KV, et al. Combination therapies including cilofexor and firsocostat for bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis attributable to NASH. Hepatology. 2021;73:625–43.

Acknowledgements

BioScience Communications, New York, NY, provided writing and editorial support, which was funded by Gilead Sciences, Inc.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Gilead.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MT, CC, and RPM conceptualized the study. CC and RPM developed the study methodology. X Liu, X Lu, JX, and CTA performed formal analyses. MT, MF, AT, PT, KVK, CLB, CL, and RPM were involved in the study research and investigation process. MT, CC, and RPM wrote the original draft. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript. MT, CC, and RPM supervised the study.CC, KS and RPM were responsible for project administration. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study complies with International Conference for Harmonisation (of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use) E6(R2) Good Clinical Practice, and applicable local laws and regulations. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards and independent ethics committees at all participating study sites. Ethics approval was obtained from the following institutional review boards and independent ethics committees: Bellberry Human Research Ethics Committee, Saint Vincent's Hospital Sydney, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital, Westmead Hospital, Ethik-Kommission der Medizinischen Universität Wien, Ethikkommission des Landes Kaernten, Hôpital Erasme, Advarra IRB Columbia—Maryland Headquarters, Biomedical Research Ethics Board (BREB), Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (CHREB), Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board, McGill University Health Centre, Research Ethics Board, North York General Hospital, Nova Scotia Health Authority, Research Ethics Board for Health Sciences Research Involving Human Subjects, University Health Network Research Ethics Board, University of British Columbia, Clinical Research Ethics Board, William Osler Health System Research Ethics Board, The Scientific Ethics Comities for Region Capital, TUKIJA National Committee on Medical Research Ethics, Comité de Protection des Personnes Ile de France III, Ethikkommission an der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Leipzig, Ethikkommission der Ärztekammer des Saarlandes, Ethikkommission der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Ethikkommission der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Ethik-Kommission der Landesärztekammer Rheinland-Pfalz, Ethik-Kommission der Medizinischen Fakultät Heidelberg, Ethikkommission der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover, Ethikkommission der Medizinischen, Fakultat Essen Institut fur Pharmakologie Universitatsklinikum, Ethikkommission des Fachbereichs Medizin der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Ethik-Kommission II der Medizinischen Fakultät Mannheim der Universität Heidelberg, Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales Berlin, Geschäftsstelle der Ethik-Kommission des Landes Berl, Carmel Medical Center Helsinki Committee, Emek Medical Center, Hadassah University Hospital Ethics Helsinki Committee, Rabin Medical Center Ethics Helsinki Committee, Rambam Health Care Campus Ethics Helsinki Committee, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Institutional Review Board, Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center Ethics Helsinki Committee, The Chaim Sheba Medical Center Ethics Helsinki Committee, A.O.U. Policlinico Paolo Giaccone, Azienda Ospedaliera Policlinico di Modena, Comitato Etico Provinciale di Modena, Comitato Etico dell’Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemel, Comitato Etico della Provincia Monza Brianza, Comitato Etico dell'Azienda Ospedaliera Ospedali Riuniti di Foggia, Comitato Etico dell'IRCCS Istituto Clinico Humanitas, Comitato Etico Interaziendale Novara, Comitato Etico Milano Area 2, Comitato Etico per la Sperimentazione Clinica della Provincia di Padova, Comitato Etico Regionale delle Marche, Chiba University Hospital, Ehime University Hospital Institutional Review Board, Hiroshima University hospital IRB, Juntendo University Hospital, Nagasaki Medical Center, Okayama University Hospital, Osaka University Hospital, Teikyo University Hospital, Tohoku University Hospital Institutional Review Board, Yamagata University Hospital, Health and Disability Committees, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon, Research Ethics Committee—South Central—Hampshire A, Advarra IRB Columbia—Maryland Headquarters, Baylor Institutional Review Board, Baylor Scott and White Research Institute, Brany-IRB, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Institutional Review Board, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Institutional Review Board, Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, Committee on Clinical Investigation Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board, Georgetown University Institutional Review Board, Henry Ford Health System Institutional Review Board, Human Research Protection Program—Health Science Committee, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Program for the Protection of Human Subjects, Intermountain Healthcare—Institutional Review Board, IRBMED, Kansas University Medical Center, Human Subjects Committee, Mayo Clinic, Institutional Review Board, Medical University of South Carolina, Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects, Mercy Medical Center, Institutional Review Board, NYU IRB, Ochsner Institutional Review Board, Penn State College of Medicine Institutional Review Board, Reading Hospital Occupational Health Services—West Reading, Regional Health Command-Central Institutional Review Board, Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board, Office of Research Affairs, UCLA Office of the Human Research Protection Program, University of California at Davis, Office of Human Research Protection, University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division IRB, University of Tennessee Health Science Center IRB, University of Utah IRB, University of Vermont, Research Protections Office, Committees on Human Research, University of Virginia Institutional Review Board for Health Sciences Research, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center IRB, Weill Cornell Medical College—Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center, Western Institutional Review Board, and Western IRB, Yale—New Haven Hospital. Informed consent is obtained from all individual participants. The study was designed and conducted by the sponsor (Gilead Sciences, Inc., Foster City, CA, USA) in collaboration with the principal investigators according to the protocol.

Consent for publication

Not applicable, this manuscript does not contain individual person data.

Competing interests

MT consults, is on the speakers’ bureau, and has received grants from Gilead, Falk, Intercept, and MSD; consults and has received grants from Albireo; consults for BiomX, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genfit, Janssen, Novartis, Phenex, Pliant, Regulus, and Shire; is on the speakers’ bureau for BMS and Roche; and has received grants from Alnylam, CymaBay, Takeda, and UltraGenyx. CC, KS, X Liu, X Lu, and JX are employed by and own stock in Gilead. CT-A receives funding from Gilead; serves as a medical advisor to Profound Medical and Promaxo; and is an independent contractor for Medscape. ZDG has no personal conflicts of interest with respect to this work; his institution currently receives funding to support his research from Gilead, BMS, CymaBay, Eiger, Inventiva, MSD, NGM, and Novartis. MF has received grant support from Gilead; and is participating in a clinical trial of norUDCA in a study sponsored by Falk. AT consults for Gilead, EA Pharma, and GSK; and has received grants from AbbVie and Chugai. PT is on the speakers’ bureau of Falk and Intercept; consults and has received grants from Gilead, BMS, Falk, Intercept, LifeArc, Medical Research Foundation, National Institute of Health Research, Perspectum, and Wellcome Trust; and is an advisor for CymaBay, Falk, Intercept, and Pliant. KVK has received grant support from Gilead, 89bio, BMS, Celgene, Corcept, CymaBay, Enanta, Genfit, GSK, Hanmi, HighTide, Intercept, Madrigal, Metacrine, Mirum, NGM, Pfizer, Pliant, Protagonist, Terns, and Viking; serves as a consultant and on advisory boards for Gilead, 89bio, CymaBay, Enanta; Genfit, HighTide, Inipharm, Intercept, Madrigal, Mirum, NGM, and Pfizer, and Enanta; and is on speakers’ bureaus for Gilead, AbbVie, and Intercept. CLB advises and has received grants from Gilead, CymaBay, Eli Lilly, and Intercept; advises BiomX, Parvus, Patara, and Pliant; and has received grants from Arena, BMS, Genkyotex, GSK, and Takeda. CL advises and has received grants from Gilead, Cara, CymaBay, Genfit, Genkyotex, GSK, Intercept, Mirum, Pliant, and Target RWE; advises Escient and Teva; and has received grants from Alnylam, Mitsubishi, NGM, Novartis, and Zydus. RPM was formerly employed by Gilead.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Trauner, M., Chung, C., Sterling, K. et al. PRIMIS: design of a pivotal, randomized, phase 3 study evaluating the safety and efficacy of the nonsteroidal farnesoid X receptor agonist cilofexor in noncirrhotic patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. BMC Gastroenterol 23, 75 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02653-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-023-02653-2