Abstract

Background

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a highly aggressive malignancy in elderly patients. Our goal is aimed to construct a novel nomogram to predict cancer-specific survival (CSS) in elderly GBC patients.

Method

We extracted clinicopathological data of elderly GBC patients from the SEER database. We used univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to select the independent risk factors of elderly GBC patients. These risk factors were subsequently integrated to construct a predictive nomogram model. C-index, calibration curve, and area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) were used to validate the accuracy and discrimination of the predictive nomogram model. A decision analysis curve (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical value of the nomogram.

Result

A total of 4241 elderly GBC patients were enrolled. We randomly divided patients from 2004 to 2015 into training cohort (n = 2237) and validation cohort (n = 1000), and patients from 2016 to 2018 as external validation cohort (n = 1004). Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis found that age, tumor histological grade, TNM stage, surgical method, chemotherapy, and tumor size were independent risk factors for the prognosis of elderly GBC patients. All independent risk factors selected were integrated into the nomogram to predict cancer-specific survival at 1-, 3-, and 5- years. In the training cohort, internal validation cohort, and external validation cohort, the C-index of the nomogram was 0.763, 0.756, and 0.786, respectively. The calibration curves suggested that the predicted value of the nomogram is highly consistent with the actual observed value. AUC also showed the high authenticity of the prediction model. DCA manifested that the nomogram model had better prediction ability than the conventional TNM staging system.

Conclusion

We constructed a predictive nomogram model to predict CSS in elderly GBC patients by integrating independent risk factors. With relatively high accuracy and reliability, the nomogram can help clinicians predict the prognosis of patients and make more rational clinical decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a relatively rare but highly aggressive malignancy. Worldwide, GBC accounts for 1.2% of all cancer diagnoses and is the 22nd most common cancer, but 1.7% of all cancer deaths make it the 17th most deadly malignancy [1]. The incidence of GBC is higher in females than in males and in developing countries than in developed countries [2, 3]. Other risk factors for gallbladder cancer include obesity, family history, hepatitis virus infection, and most importantly, gallstones and chronic cholecystitis [2]. In recent years, the incidence of GBC is increasing in many countries and regions around the world, especially in Asia [4,5,6,7]. Furthermore, elderly GBC patients have a higher incidence, higher morbidity, and shorter overall survival [8, 9]. Gallbladder cancer patients are mainly middle-aged and elderly people. In the United States, about 97% of gallbladder cancer patients are 45 years and older, and 71% of gallbladder cancer patients are 65 years and older [10]. Therefore, the survival prognosis of elderly GBC patients deserves our careful attention.

As far as we know, the eighth American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system is more practical to predict all stages of gallbladder cancer and does not accurately estimate the prognosis of individual patients [11]. Thus, a nomogram that includes various factors is needed to predict the prognosis of a specific group of patients. In oncology and medical research, a nomogram is a common tool for assessing the prognosis of individual patients because of its friendly and feasible interface [12]. Up to now, many gallbladder cancer-related nomogram prediction models have been established [13,14,15]. However, to our knowledge, no nomograms have been developed specifically to predict a specific population of elderly patients with gallbladder cancer. Aiming at elderly GBC patients, it is necessary to establish a more targeted, reliable, and practical prediction model to predict CSS.

This study aimed to select prognosis-related risk factors and integrate them to construct a nomogram for predicting the cancer-specific survival of elderly GBC patients so that can help clinicians better judge prognosis and make clinical decisions.

Materials and methods

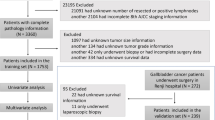

Data retrieved from SEER

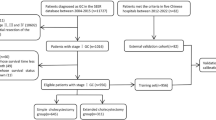

Clinicopathological data and prognosis of all patients with GBC from 2004 to 2018 were retrieved from the SEER database. Considering that SEER is a public database from which anyone can access data, and private patient information is not identifiable, informed consent of patients or ethical approval is not required. We performed the analysis in accordance with the SEER database usage rules. Clinical variables that we collected included sex, age, race, the status of marriage, year of diagnosis, tumor stage, tumor profile, histological grade, tumor size, radiation, chemotherapy, and surgical method. The above clinical variables covered demographic characteristics, tumor information, and treatment modalities, which is very comprehensive. The inclusion criteria included: (1) The years of diagnosis were 2004–2018; (2) Aged 65 years or older; (3) Pathological diagnosis identified GBC. The exclusion criteria included: (1) Unknown tumor size; (2) Surgical method unknown; (3) Survival time unknown or less than 1 month; (4) The cause of death is unknown; (5) Unknown TNM stages. A total of 4241 elderly GBC patients were enrolled in this study. Patients with GBC diagnosed between 2004 and 2015 were randomly divided into the training cohort (70%) and the internal validation cohort (30%), and patients diagnosed between 2016 and 2018 were defined as the external validation cohort (Fig. 1).

Nomogram development and statistical analysis

The specific statistical description and statistical analysis methods are consistent with our previous paper [16]. Briefly, the training cohort was used (n = 2237) to establish the nomogram and to predict the nomogram model using both the internal cohort (n = 1000) and external cohort (n = 1004). The independent risk factors of elderly GBC patients were selected by univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis. Then a predictive nomogram model using all these risk factors was set up. Subsequently, the calibration curve, decision analysis curve (DCA), Consistency Index (C-index), and area under the receiver operating curve (AUC) were applied for validating the accuracy and discriminating the predictive nomogram model. Finally, based on the nomogram scores, the patients were divided into low-risk and high-risk groups and compared the differences in CSS between the two groups using survivorship curves. Statistical analysis was performed using R software 4.1.0 and SPSS 26.0. P< 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Result

Clinical features

A total of 4241 patients with GBC diagnosed in 2004–2018 and aged 65 and older were included in the study. Among patients from 2004 to 2015, the average age was 76.6 ± 7.37 years, 2492 (77.0%) patients were white, 1014 (31.3%) patients were male, and 1541 (47.6%) patients were married. The histological grades I, II, III, and IV was 396 (12.2%), 1189 (36.7%), 1040 (32.1%), and 82 (2.53%), respectively. The remaining 530 (16.4%) have unknown stages. The histological type was adenocarcinoma in 2370 (73.2%) patients and non-adenocarcinoma in the rest of 867 (26.8%) patients. The distribution of histological subtypes of non-adenocarcinoma is shown in Fig. S1. There were 1290 patients (39.9%) diagnosed in the year 2004–2009 and the rest of 1947 patients (60.1%) in 2010–2015. There were 554 (17.1%), 1223 (37.8%), 1321 (40.8%), and 139 (4.29%) patients with stage T1, T2, T3, and T4 tumors, respectively. The mean tumor size is 38.0 ± 26.9 mm. Radical surgery was performed in 2132 (65.9%) patients, simple or partial surgery was performed in 545 (16.8%) patients, and 560 (17.3%) patients did not have any surgery. 1015 (31.4%) patients underwent chemotherapy and 2222 (68.6%) did not undergo chemotherapy or were unknown. 517 (16.0%) patients received radiation therapy, and 2720 (84.0%) received no radiation therapy or unknown. The clinical and pathological data of all patients are shown in Table 1.

Independent risk factors in the training cohort

We used univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression models in the training cohort to identify the risk factors of elderly GBC patients. Univariate Cox regression analysis found that age, TNM stage, tumor size, histological grade of the tumor, surgical methods, and chemotherapy were associated with prognosis. While sex, marital status, race, year of diagnosis, and histological type were not statistically significantly associated with prognosis. All the risk factors screened by the univariate Cox analysis were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis, and the results showed that all the included factors were independent risk factors for patient prognosis (Table 2).

Construction and validation of the prognostic nomogram

We included all the independent risk factors to build a nomogram for predicting 1-, 3-, and 5-year CSS in elderly GBC patients (Fig. 2). As the nomogram shows, T stage and tumor size were the most statistically significant risk factors affecting cancer-specific survival, after that tumor histological grade, age, distant metastasis, and surgery. Besides, chemotherapy and lymph node metastasis also affect patient outcomes. The C-index of the nomogram was 0.763[0.757–0.769], 0.756[0.746–0.766], and 0.786[0.774–0.798] in the training, validation, and external validation cohort, respectively. It manifested that the prediction model had a good prediction ability. In both the training cohort and the internal validation cohort, the calibration curves show that the predicted values of the nomogram agree well with the observed values (Fig. 3), which confirmed its high accuracy. Besides, the receiver operating characteristic curve also indicated the high authenticity of the prediction model (Fig. 4).

Clinical application of the nomogram

DCA manifested that the nomogram model had better prediction ability than the conventional TNM staging system (Fig. 5). All patients were divided into the high-risk group (total > 168) and the low-risk group (total ≤ 168) according to the individual score of the nomogram. In the training and validation cohort, survival was significantly higher in the low-risk group than in the high-risk group (Fig. 6). The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rates in the high-risk group were 32.7, 12.2, and 9.0%, respectively. The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rates in the low-risk group were 82.1, 58.7, and 51.8%, respectively. In the low-risk group, the effect of the surgical method on survival was not statistically significant (Fig. 7A). In the high-risk group, the survival of patients who received radical surgery was the highest (Fig. 7B).

Decision curve analysis of the nomogram in the training cohort (A), validation cohort (B), and external validation cohort (C). The Y-axis represents a net benefit, and the X-axis represents threshold probability. The green line means no patients died, and the dark green line means all patients died. When the threshold probability is between 25 and 80%, the net benefit of the model exceeds all deaths or none

Discussion

Nomogram as a prediction tool is commonly used to estimate prognosis in oncology and medicine [12]. By far, it has been used in various cancers, such as liver [17,18,19], pancreas [20, 21], kidney [22, 23], and bone [24,25,26] et al. Besides, Bai et al. [13] constructed a nomogram to predict overall survival after gallbladder cancer resection in China. Cai et al. constructed a nomogram to predict distant metastasis in T1 and T2 gallbladder cancer [14]. Chen et al. developed a nomogram to predict overall survival in node-negative gallbladder cancer patients [15]. Nevertheless, the survival prognosis of patients with gallbladder cancer varies greatly with age, and elderly patients with GBC have higher morbidity and shorter overall survival. Therefore, we developed and validated the nomogram based on patients, tumor characteristics, and treatment methods to estimate the CSS of elderly GBC patients.

In our study, we made statistical descriptions and statistical analyses of elderly GBC patients from the SEER database. We randomly divided patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2015 into the training cohort and the internal validation cohort, and patients diagnosed between 2016 and 2018 were defined as the external validation cohort. There was no statistical difference between the training group and the validation group regarding age, race, year of diagnosis, histological grade, TNM stage, chemotherapy, and so on. Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis found that numerous factors significantly affected CSS, including age, histological tumor grade, TNM stage, surgery, chemotherapy, and tumor size. While other variables such as sex, marriage, year of diagnosis, race, and histological type were not identified as prognostic significance. Our study shows that the difference between the elderly group of GBC patients and whole GBC patients does exist, and further investigation is required.

There have been some developments in the treatment concept for patients with GBC. Previous studies show that surgery is the only treatment modality associated with a benefit in terms of survival [27, 28]. However, recent studies found that other treatment methods such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy can also produce benefits for gallbladder cancer patients [29], this is partly because of the development of sequencing technology and new drugs so that the treatment can be more precise. In addition, Mao et al. also found that “Surgery + Chemotherapy” treatment can provide survival benefits for patients with advanced GBC [30]. Recent studies have reported that the widely-used gemcitabine in combination with oxaliplatin (GEMOX) or cisplatin and tegafur in combination with oxaliplatin (SOX) is an effective chemotherapy regimen for patients with gallbladder cancer [30,31,32]. Our study found that patients who undergo chemotherapy have a better prognosis, paralleling recent studies. Nevertheless, surgery remains the cornerstone treatment for GBC patients. In our study, simple/partial surgery and radical surgery have similar benefits. In fact, there are only 25%–30% of total GBC patients undergo radical resection, partly due to many patients with gallbladder cancer are admitted to the hospital at an advanced stage and approximately two-thirds of gallbladder cancers are diagnosed accidentally in patients undergoing surgery for gallstones and cholecystitis (also known as “incidental gallbladder cancer, or IGBC”), inevitably leading to partial resection and simple surgery in patients, respectively [30, 33].

Among the nomogram tumor characteristics (pathological grade, TNM stage, tumor size), the T stage has the most significant effect on CSS. The risk of the T3 and T4 stages is significantly higher than that of the T1 and T2 stages. Lim et al. found that in patients with GBC after surgical resection, the TNM stage was the most important prognostic factor [34]. Groot et al. found that the prognosis of GBC patients depends strongly on the T stage, as well as the presence of lymph node metastasis, surgical resection margin, and tumor differentiation [35]. Compared with previous studies, our results consistently reflect the relationship between the T stage and CSS and quantify its impact on CSS in specific populations. Notably, age remains an important prognostic factor for patients aged 65 years or older with gallbladder cancer. This may be attributed to GBC being mostly diagnosed in the elderly, with the average age of GBC diagnosis in the US being 72 [2], which further proved the necessity of our research.

Our nomogram showed that in the training cohort, the AUC of 1-, 3-, 5-year CSS is 0.828 (95%CI:0.810–0.846), 0.815 (95%CI:0.796–0.834), and 0.813 (95%CI:0.790–0.836) respectively. In the internal validation cohort, the AUC of 1-, 3-, 5-year CSS is 0.821 (95%CI:0.792–0.850), 0.830 (95%CI:0.802–0.859), and 0.835 (95%CI:0.801–0.869) respectively. It indicates that our nomogram predicts the CSS of elderly GBC patients with a high degree of authenticity. In addition, DCA curves were also drawn to evaluate the clinical application value of the nomogram which showed that compared with the traditional TNM staging method, the nomogram could more accurately predict the CSS of elderly GBC patients at 1-, 3- and 5 years.

Nevertheless, there are some limitations in our study that should be considered. First, our study was based only on the SEER database. The results are not necessarily fully representative of other parts of the world outside of the USA, such as Asia, Africa, South America, etc. Second, the predictive nomogram does not include important factors such as tumor marker CA199, molecular factors, and the results of genetic diagnosis. Third, the data of our external validation cohort is also from the SEER database, which inevitably leads to relatively weak validation.

Conclusion

Through statistical description and analysis, we found that the independent risk factors for tumor-specific survival in elderly patients with gallbladder cancer included age, tumor histological grade, TNM stage, surgical method, chemotherapy, and tumor size. More importantly, we constructed a predictive nomogram model to predict CSS in elderly GBC patients by integrating these risk factors. With relatively high accuracy and reliability, the nomogram can help clinicians predict the prognosis of patients and make more rational clinical decisions.

Availability of data and materials

The SEER data analyzed in this study is available at https://seer.Cancer.gov/.

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 Epub 2018 Sep 12. Erratum in: CA Cancer J Clin. 2020 Jul;70(4):313. PMID: 30207593.

Rawla P, Sunkara T, Thandra KC, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of gallbladder cancer. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2019;5(2):93–102. https://doi.org/10.5114/ceh.2019.85166 Epub 2019 May 23. PMID: 31501784; PMCID: PMC6728871.

Sharma A, Sharma KL, Gupta A, Yadav A, Kumar A. Gallbladder cancer epidemiology, pathogenesis and molecular genetics: recent update. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(22):3978–98. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i22.3978 PMID: 28652652; PMCID: PMC5473118.

Huang J, Patel HK, Boakye D, Chandrasekar VT, Koulaouzidis A, Lucero-Prisno Iii DE, Ngai CH, Pun CN, Bai Y, Lok V, Liu X, Zhang L, Yuan J, Xu W, Zheng ZJ, Wong MC. Worldwide distribution, associated factors, and trends of gallbladder cancer: a global country-level analysis. Cancer Lett. 2021;521:238–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.004 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34506845.

Malhotra RK, Manoharan N, Shukla NK, Rath GK. Gallbladder cancer incidence in Delhi urban: a 25-year trend analysis. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54(4):673–7. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijc.IJC_393_17 PMID: 30082556.

Nie C, Yang T, Liu L, Hong F. Trend analysis and risk of gallbladder cancer mortality in China, 2013-2019. Public Health. 2022;203:31–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.12.002 Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35026577.

Wi Y, Woo H, Won YJ, Jang JY, Shin A. Trends in Gallbladder Cancer Incidence and Survival in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50(4):1444–51. https://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2017.279 Epub 2018 Jan 24. PMID: 29370591; PMCID: PMC6192934.

Tanaka S, Kubota D, Lee SH, Oba K, Yamamoto T, Ikebe T, Kubo S, Matsuyama M. Latent gallbladder carcinoma in a young adult patient with acute cholecystitis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37(8):713–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-007-3464-1 Epub 2007 Jul 26. PMID: 17643222.

Gupta S, Gulwani HV, Kaur S. A Comparative Analysis of Clinical Characteristics and Histomorphologic and Immunohistochemical Spectrum of Gallbladder Carcinoma in Young Adults (< 45 Years) and Elderly Adults (> 60 Years). Indian J Surg Oncol. 2020;11(2):297–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13193-020-01044-3 Epub 2020 Feb 6. PMID: 32523278; PMCID: PMC7260299.

Van Dyke AL, Shiels MS, Jones GS, Pfeiffer RM, Petrick JL, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Koshiol J. Biliary tract cancer incidence and trends in the United States by demographic group, 1999–2013. Cancer. 2019;125(9):1489–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.31942 Epub 2019 Jan 15. PMID: 30645774; PMCID: PMC6467796.

Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, Meyer L, Gress DM, Byrd DR, Winchester DP. The eighth edition AJCC Cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–9. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21388 Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 28094848.

Balachandran VP, Gonen M, Smith JJ, DeMatteo RP. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(4):e173–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71116-7 PMID: 25846097; PMCID: PMC4465353.

Bai Y, Liu ZS, Xiong JP, Xu WY, Lin JZ, Long JY, Miao F, Huang HC, Wan XS, Zhao HT. Nomogram to predict overall survival after gallbladder cancer resection in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(45):5167–78. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v24.i45.5167 PMID: 30568393; PMCID: PMC6288645.

Cai YL, Lin YX, Jiang LS, Ye H, Li FY, Cheng NS. A novel Nomogram predicting distant metastasis in T1 and T2 gallbladder Cancer: a SEER-based study. Int J Med Sci. 2020;17(12):1704–12. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.47073 PMID: 32714073; PMCID: PMC7378661.

Chen M, Cao J, Zhang B, Pan L, Cai X. A Nomogram for prediction of overall survival in patients with node-negative gallbladder Cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10(14):3246–52. https://doi.org/10.7150/jca.30046 PMID: 31289596; PMCID: PMC6603372.

Wen C, Tang J, Luo H. Development and validation of a Nomogram to predict Cancer-specific survival for middle-aged patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Public Health. 2022;10:848716. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.848716 PMID: 35296046; PMCID: PMC8918547.

Zhuang H, Zhou Z, Ma Z, Huang S, Gong Y, Zhang Z, Hou B, Yu W, Zhang C. Prognostic stratification based on a novel Nomogram for solitary large hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Front Oncol. 2020;10:556489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.556489 PMID: 33312945; PMCID: PMC7703492.

Fang Q, Yang R, Chen D, Fei R, Chen P, Deng K, Gao J, Liao W, Chen H. A novel Nomogram to predict prolonged survival after hepatectomy in repeat recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:646638. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2021.646638 PMID: 33842361; PMCID: PMC8027067.

Chen SH, Wan QS, Zhou D, Wang T, Hu J, He YT, Yuan HL, Wang YQ, Zhang KH. A simple-to-use Nomogram for predicting the survival of early hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Front Oncol. 2019;9:584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2019.00584 PMID: 31355135; PMCID: PMC6635555.

He C, Sun S, Zhang Y, Lin X, Li S. Score for the overall survival probability of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the body and tail after surgery: a novel Nomogram-based risk assessment. Front Oncol. 2020;10:590. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00590 PMID: 32426278; PMCID: PMC7212341.

Zou Y, Han H, Ruan S, Jian Z, Jin L, Zhang Y, Chen Z, Yin Z, Ma Z, Jin H, Dai M, Shi N. Development of a Nomogram to predict disease-specific survival for patients after resection of a non-metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic body and tail. Front Oncol. 2020;10:526602. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.526602 PMID: 33194585; PMCID: PMC7658586.

Wang J, Zhanghuang C, Tan X, Mi T, Liu J, Jin L, Li M, Zhang Z, He D. Development and validation of a Nomogram to predict distant metastasis in elderly patients with renal cell carcinoma. Front Public Health. 2022;9:831940. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.831940 PMID: 35155365; PMCID: PMC8831843.

Wang J, Tang J, Chen T, Yue S, Fu W, Xie Z, Liu X. A web-based prediction model for overall survival of elderly patients with early renal cell carcinoma: a population-based study. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03287-w PMID: 35164796; PMCID: PMC8845298.

Wang J, Zhanghuang C, Tan X, Mi T, Liu J, Jin L, Li M, Zhang Z, He D. A Nomogram for predicting Cancer-specific survival of osteosarcoma and Ewing's sarcoma in children: a SEER database analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:837506. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.837506 PMID: 35178367; PMCID: PMC8843936.

Chen B, Zeng Y, Liu B, Lu G, Xiang Z, Chen J, Yu Y, Zuo Z, Lin Y, Ma J. Risk factors, prognostic factors, and Nomograms for distant metastasis in patients with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma: a population-based study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:672024. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2021.672024 PMID: 34393996; PMCID: PMC8362092.

Wu G, Zhang M. A novel risk score model based on eight genes and a nomogram for predicting overall survival of patients with osteosarcoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):456. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-06741-4 PMID: 32448271; PMCID: PMC7245838.

Sasaki R, Itabashi H, Fujita T, Takeda Y, Hoshikawa K, Takahashi M, Funato O, Nitta H, Kanno S, Saito K. Significance of extensive surgery including resection of the pancreas head for the treatment of gallbladder cancer--from the perspective of mode of lymph node involvement and surgical outcome. World J Surg. 2006;30(1):36–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-0181-z PMID: 16369715.

Shrikhande SV, Barreto SG. Surgery for gallbladder cancer: the need to generate greater evidence. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;1(1):26–9. https://doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v1.i1.26 PMID: 21160792; PMCID: PMC2999113.

Javle M, Zhao H, Abou-Alfa GK. Systemic therapy for gallbladder cancer. Chin Clin Oncol. 2019;8(4):44. https://doi.org/10.21037/cco.2019.08.14 PMID: 31484490; PMCID: PMC8219347.

Mao W, Deng F, Wang D, Gao L, Shi X. Treatment of advanced gallbladder cancer: a SEER-based study. Cancer Med. 2020;9(1):141–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.2679 Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID: 31721465; PMCID: PMC6943088.

Malik IA, Aziz Z, Zaidi SH, Sethuraman G. Gemcitabine and Cisplatin is a highly effective combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced cancer of the gallbladder. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26(2):174–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000421-200304000-00015 PMID: 12714891.

Komaki H, Onizuka Y, Mihara K, Seita M, Maeda M, Nakamura S. Successful treatment with tegafur and PSK in a patient with gallbladder cancer. Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. 1988;15(9):2801–4 Japanese. PMID: 3137892.

Jin K, Lan H, Zhu T, He K, Teng L. Gallbladder carcinoma incidentally encountered during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: how to deal with it. Clin Transl Oncol. 2011;13(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12094-011-0613-1 PMID: 21239352.

Lim H, Seo DW, Park DH, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH, Hwang S. Prognostic factors in patients with gallbladder cancer after surgical resection: analysis of 279 operated patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47(5):443–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182703409 PMID: 23188077.

Groot Koerkamp B, Fong Y. Outcomes in biliary malignancy. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110(5):585–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23762 PMID: 25250887.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Methods

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province, China (Joint Research Fund, No. 2019YFH0056).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT and CW designed the study; CW, JT, TW, and HL collected the data and performed statistical analysis; CW wrote the initial manuscript; CW and JT modified the article with prudence according to the result of our group discussion; CW, JT, TW, and HL reviewed and edited the article; JT and CW are co-first authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Considering that SEER is a public database from which anyone can access data, and private patient information is not identifiable, informed consent of patients or ethical approval is not required.

Consent for publication

None.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Histological type of gallbladder carcinoma in all patients. The vast majority of patients were adenocarcinoma, followed by squamous cell carcinoma, endocrine carcinoma, and some unknown epithelial tumors.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wen, C., Tang, J., Wang, T. et al. A nomogram for predicting cancer-specific survival for elderly patients with gallbladder cancer. BMC Gastroenterol 22, 444 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02544-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02544-y