Abstract

Background

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is a class I carcinogen in gastric carcinogenesis, but its role in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is unknown. Therefore, we aimed to explore the possible relationship.

Methods

We reviewed observational studies published in English until October 2019. Summary odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for included studies.

Results

46 studies from 1505 potential citations were eligible for inclusion. A significant inverse relationship with considerable heterogeneity was found between Hp (OR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51–0.96; P = 0.03) and BE, especially the CagA-positive Hp strain (OR = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.15–0.54; P = 0.0002). However, Hp infection prevalence was not significantly different between patients with BE and the gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) control (OR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.82–1.19; P = 0.92). Hp was negatively correlated with long-segment BE (OR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.25–0.90; P = 0.02) and associated with a reduced risk of dysplasia. However, Hp had no correlated with short-segment BE (OR = 1.11; 95% CI, 0.78–1.56; P = 0.57). In the present infected subgroup, Hp infection prevalence in BE was significantly lower than that in controls (OR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54–0.89; P = 0.005); however, this disappeared in the infection history subgroup (OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.43–1.78; P = 0.73).

Conclusions

Hp, especially the CagA-positive Hp strain, and BE are inversely related with considerable heterogeneity, which is likely mediated by a decrease in GERD prevalence, although this is not observed in the absence of current Hp infection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Owing to improvements in hygiene and living conditions, the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (Hp) has continued to fall in developed countries, along with the incidence of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer, although it remains high in some developing countries, such as 70.1% in Africa [1, 2]. Interestingly, in contrast to the decline in the rate of Hp infection, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinomas (EAC) has increased significantly. Current epidemiological studies present a consistent, rapidly increasing incidence of EAC in the United States and most other western countries, especially among males, with an observed or estimated start between 1960 and 1990, while the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma is stable or declining in all racial groups [3, 4]. The etiology of EAC is multifactorial, and Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a premalignant lesion that is observed in the majority of patients with EAC, and carries a risk of eventual development of EAC that is up to 30- to 125-fold higher than that in patients without this condition [5, 6]. Previous studies have identified several risk factors for the development of BE, including male sex, older age, smoking, white race, obesity, hiatal hernia, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [7, 8]. However, the possible role of Hp in BE is uncertain. Currently, Hp is classified by the World Health Organization as a class 1 carcinogen, since it promotes gastric cancer, and is also regarded as a commensal organism that confers some protection against asthma, allergies, and even obesity [9, 10]. Hp seems to have a protective influence on BE, however, the relationship between Hp and BE remains controversial.

Multiple studies have highlighted the relationship between Hp and BE [11,12,13]. Recently, Wang used individual-level data from six case–control studies to conduct analysis. Their study provided evidence that Hp infection was strongly inversely associated with BE, which was even stronger among individuals with cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) positive strain [14]. Another extensive meta-analysis also demonstrated that Hp infection was associated with a reduced risk of BE, and dysplastic, non-dysplastic, and long-segment BE (LSBE), and demonstrated that the risk reduction was not correlated with geographical location [15]. However, some researchers concluded that there was no clear association between Hp and BE, or demonstrated contrary conclusions in case–control studies and cohort studies [16, 17]. Fischbach’s meta-analysis of 49 observational studies identified a protective effect of Hp on BE, and showed great heterogeneity between the majority of studies, which was potentially due to selection and information bias [18]. Consequently, it is understandable that different meta-analyses come to different conclusions.

Previous meta-analysis results are inconsistent, and the heterogeneity between them may derive from selection of the control group, the definition of BE, and the Hp detection method. To better understand this relationship, we performed meta-analysis and subgroup analysis based on the potential sources of heterogeneity. This study would contribute to the design of clinical studies and the decisions on whether to eradicate Hp.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, EMBASE, and COCHRANE databases were searched from inception to October 2019. We used the following MeSH terms or keywords as search terms: (("Barrett Esophagus"[Mesh]) OR (Barrett metaplasia) OR (Barrett metaplasias) OR (Barrett’s Metaplasia) OR (Metaplasia, Barrett) OR (Metaplasias, Barrett) OR (Barrett’s Syndrome) OR (Barretts syndrome) OR (Barrett Syndrome) OR (Barrett’s Esophagus) OR (Barrett’s oesophagus) OR (Barretts Esophagus) OR (Barretts oesophagus) OR (Esophagus, Barrett’s) OR (oesophagus, Barrett’s) OR (Esophagus, Barrett) OR (oesophagus, Barrett) OR (Barrett Epithelium) OR (Epithelium, Barrett) OR (Barrett’s) OR (Barrett)) AND (("Helicobacter pylori"[Mesh]) OR (Helicobacter pylori) OR (H pylori) OR (H. pylori) OR (Helicobacter) OR (Campylobacter)) AND (Humans).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All eligible studies satisfied the following inclusion criteria:

-

1.

Observational studies: Case–control, cohort, or cross-sectional studies

-

2.

Providing raw data on Hp infection in the BE and control groups

-

3.

Studies conducted in adult populations

Studies with the following exclusion criteria were eliminated:

-

1.

Full-text articles in languages other than English

-

2.

Studies in which the data came from a review article or other non-full-text article

-

3.

Less than five points in the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS)

When the same data appeared in different articles, only the study with the most complete relevant data was included.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two independent investigators after reading each included study. When agreement was reached by discussion or with the help of third investigators, the data were recorded in a designed Excel 2019 sheet. We collected data on author, year of publication, journal, geographical location, study type, Hp infection testing methods, definition of cases and controls, number of cases and controls, number of Hp infections in cases and controls, and whether matched in sex, age, obesity, smoking, alcohol, and race. Data on dysplasia, segment length and infection of CagA-positive Hp strain were included when present. When the subjects of multiple reports are the same. Only one, the most complete, would be included.

Statistical analysis

Our primary objective was to compare the prevalence of Hp infection between BE groups and controls. The secondary objective was to conduct subgroup analysis according to the differences in definitions of the control group, the definitions of BE, and the Hp detection methods, in order to clarify the impact of these aspects on the overall results. The correlation between Hp and BE was determined by calculating the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk. The results of the meta-analysis were displayed on a forest map, heterogeneity was assessed using Cochrane's Q and I2 statistics, and publication biases were checked by visual assessment of funnel plots. Heterogeneity was regarded as moderate, substantial, and considerable when the I2 was between 30–60%, 50–90%, and 75–100%, respectively. All calculations were conducted by Review Manager 5.3.

Results

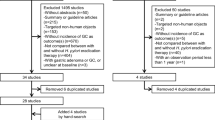

Searches initially generated 1505 potential citations after removing 546 duplicates from 2051 citations. A large sample study (n = 1445) was further excluded by screening titles, abstracts, and browsing full-text. A total of 62 studies remained for full-text review, and six studies without original data [19,20,21,22,23,24]. and seven studies with less than five points in NOS were additionally excluded [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Three studies were excluded because of repetitive research subjects [32,33,34]. Finally, Forty-five studies were included in this article; data from 36 of these were extracted to explore the relationship between Hp and BE, while others examined the correlation in Hp and BE dysplasia, lengths of BE, and the correlation between the CagA-positive Hp strain and BE. The study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Prevalence of Hp infection in BE and controls

The 36 included studies comprised a total of 90,895 BE patients and 430,846 controls [11,12,13, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. A summary of the characteristics of these studies is shown in Table 1. The prevalence of Hp infection in BE patients was significantly lower than that in controls (OR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51–0.96; P = 0.03), with considerable heterogeneity observed between studies (I2 = 98%, P < 0.00001) (Fig. 2). Funnel plots suggested no obvious publication bias (Fig. 3). Subgroup analysis was conducted according to differences in definition of control group. Fourteen studies regarded patients with GERD as control group [37, 43, 49, 52, 54, 55, 58,59,606263, 6466, 67]. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of Hp infection between BE and GERD controls (OR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.82–1.20; P = 0.91; I2 = 33%). In contrast, the negative relationship between Hp prevalence and BE was enhanced when defining subjects undergoing endoscopy in another 14 studies (OR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.31–0.95; P = 0.03; I2 = 99%) or normal control (population or primary care people) in four studies (OR = 0.48; 95% CI, 0.38–0.61; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0%) as control groups (Fig. 4) [11, 13, 35, 36, 38, 40,41,42, 44,45,46,47,48, 50, 51, 53, 56, 57]. When BE was defined as intestinal metaplasia (IM) in 26 studies, we found an increased negative correlation between Hp prevalence and BE (OR = 0.64; 95% CI, 0.51–0.80; P = 0.0001; I2 = 90%) [11, 12, 13, 36, 38, 40, 42,43,44,45, 50, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58, 60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. However, the negative correlation disappeared (OR = 0.76; 95% CI, 0.51–1.14; P = 0.18; I2 = 92%) in the other subgroups, which diagnosed BE with columnar metaplasia (CM), endoscopic presentation, no clear definition, and gastric epithelium [35, 37, 39, 41, 46,47,48,49, 51, 59]. In addition, we divided the studies according to whether Hp could be confirmed as a present infection, into the present infected subgroup (Hp positive with rapid urease test, urea breath test, histology, or culture), infection history subgroup (Hp positive with serological detection, treatment history, or infection history), and not clear subgroup. In the present infected group with 24 studies, the prevalence of Hp infection in BE was significantly lower than that in controls (OR = 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54–0.89; P = 0.005; I2 = 92%) [11, 13, 36, 37, 39,40,41,42,43,44, 4648, 49, 51, 53, 55, 56, 60,61,62,63, 65,66,67], while the negative correlation disappeared again in the infection history subgroup (OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.43–1.78; P = 0.73; I2 = 95%) (Fig. 5) [12, 35, 38, 54, 57].

Correlation between Hp and length of BE

We extracted data from 11 studies to explore the correlation between Hp and LSBE, and obtained a total of 669 BE patients and 31,243 controls [35, 42, 45, 58, 62, 67, 68,69,70,71,72]. We found that the risk of Hp infection in patients with LSBE was significantly lower than that in the controls (OR = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.25–0.90; P = 0.02; I2 = 82%). In contrast, we extracted data from 12 studies to explore the correlation between Hp and short-segment BE (SSBE), and obtained a t otal of 7886 BE patients and 31,173 controls [35, 36, 42, 45, 58, 62, 67, 73, 70, 74,75,76]. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of Hp between the SSBE and controls (OR = 1.11; 95% CI, 0.78–1.56; P = 0.57; I2 = 68%). Although the same Hp infection rate was observed in the ultra-short-segment BE (USBE) and GERD groups (22%, 2/9 vs. 22% 7/32) in Zaninotto’s study, such a small sample size might lead to bias [67]. Matsuzaki’s research suggested that the Hp infection rate in USBE was lower than that in controls, but the difference was not significant (66.3%, 57/86 vs 72.5%,50/69; P > 0.05) [76].

Correlation between Hp and BE dysplasia

Only four previous studies have focused on whether Hp reduces the risk of BE dysplasia [11, 36, 5765]. Decades ago, Vieth found that patients with BE neoplasia (high-grade dysplasia or EAC) had significantly lower rates of Hp infection than patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia (P < 0.01), which was also lower than that observed in patients with simple BE [65]. This conclusion was further confirmed by two subsequent studies. In a population-based case–control study, Thrift determined that patients with BE had a lower likelihood of infection with Hp (OR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.22–0.61) as was observed in many other studies. The BE group was then divided into two subgroups: BE without dysplasia and BE with dysplasia, and showed a reduced negative correlation (OR = 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30–0.86) and an increased negative correlation (OR = 0.10; 95% CI, 0.03–0. 33) when compared to population control, respectively [57]. Another case–control study with many more research objects further verifi ed this fin ding. When defining cases as BE with dysplasia or cancer, instead of simple BE, the negative correlation between Hp and the cases became stronger (OR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.26–0.37 vs OR = 0.36; 95% CI, 0.34–0.38) [11]. However, a recent study in Azerbaijan, a high-prevalence area of Hp infection, directly compared BE with and without dysplasia, and found no significant difference in Hp infection between the two groups (OR = 0.42; 95% CI, 0.12–1.52; P > 0.05) [36]. Details of these studies are shown in Table 2.

Prevalen ce of CagA- positive Hp i n BE and controls

In the ten studies tha t examined patients with BE, the prevalence of the CagA-positive H p strain was significantly lower than that in controls (208/1080 [20.5%] vs 605/2070 [29.1%]) (OR = 0.28; 95% CI, 0.15–0.54, P = 0.0002; I2 = 83%) (Fig. 6) [12, 38, 45, 47, 54, 58, 59, 69, 71, 72]. In a case–control study in 2008, Corley confirmed that the inverse association between Hp and BE was stronger in subjects with the CagA-positive strain, weaker but still p resent in those with CagA-negative stra in [38]. Meanwhile, there were no substantial differences in the pattern of BE and the CagA-positive Hp stra in after adjustment for GERD symptom severity or GERD symptom frequency, which w as similar to Anderson’s conclusion [38, 69]. However, Anderson found a somewhat weaker pattern between the CagA-positive Hp strain and BE when analyzing for the CagA antig en only [69].

Description of publication bias, heterogeneity, and sensitivity analysis

A visual inspection of the funnel plot was used to assess publication bias in the studies. There was no asymmetry in the funnel plots of the respective analyses and subgroup analyses. Considerable heterogeneity was noted in meta -analyses concerning the correlation between Hp prevalence and BE. Substantial heterogeneity was also noted when analyzing the relationship between Hp and lengths of BE, and th at between the CagA-positive Hp strain and BE. Through sensitivity analyses, we found that the significant heterogeneity could be attributed to factors other than a single study. We sometimes discovered decreased heterogeneity in the following subgroup meta-analyses. In the subgroup analysis of GERD, population and primary care people, the heterogeneity decreased considerably to 33% and 0%, respectively. This finding suggests that regarding subjects undergoing endoscopy as control might be the most potential sources of heterogeneity. There was also a significant decrease in heterogeneity when subgroup analysis was performed based on whether or not a match was made for sex and age. There were many factors closely related to Hp and BE, including sex, age, smoking, alcohol consumption, race, geographic location, definition of BE and control group, methods of Hp testing. It was hard to analyze and discuss each factor due to the limited number of publications and the heterogeneity of the description.

Discussion

In accordance with recent studies, our meta-analysis showed an inverse relationship between the prevalence of Hp, especially the CagA-positive Hp strain, with BE. The conclusions of most of the previous studies are consistent with those of the current study [14, 15, 77], in that Hp is a protective factor for BE. It is generally recognized that Hp causes corpus-predominant gastritis with decreased acid secretion, which is associated with a decreased risk of GERD and BE [78, 79]. Meanwhile, Hp infection reduces the chance of regurgitation by promoting gastric emptying and reducing the incidence of ob esity [79]. In subgroup analyses, Hp infection and BE were inversely related when compared with subjects undergoing endoscopy and normal control (population or primary care people), but not GERD control. Furthermore, the prevalence of Hp was not significantly different between patients with BE and those with GERD. Combined to previous studies, this protective effect of Hp is likely mediated by a decrease in prevalence of GERD in Hp-infected patients, since it disappears in patients with GERD [14]. However, there were no substantial differences in the relationship between BE and CagA-positive Hp strains after adjustment for GERD symptom seve rity or frequency [38, 71]. It suggested that CagA-positive Hp might reduce the risk of BE in some other ways.

Although Hp has been classified as a class 1 carcinogen, the majority of infected people had no symptoms associated with Hp infection actually [1]. Nowadays, the negative associations between Hp and asthma, allergies, GERD and inflammatory bowel disease are increasingly recognized [80]. The present study also revealed the protective effect of Hp on BE. Meanwhile, long-term use of proton pump inhibitors has been shown to increase the risk of gastric cancer after confounding factors, the HRs increased with cumulative duration, cumulative omeprazole equivalents and time since treatment initiation [81, 82]. Therefore, it would be important to explore new treatment options to alleviate BE symptoms and personalize Hp eradication.

The most likely protective mechanism of Hp to BE is the effect on gastric reflux by its influence on gastric acid secretion. Usually, antral-predominant gastritis is associated with increased acid secretion, whereas corpus-predominant gastritis, often accompanied by gastric atrophy, is associated with decreased acid secretion [83]. Ten previous studies only detected Hp infection with tissue from the antrum [13, 35, 36, 39, 44, 46,47,48,49, 55]; The meta-analysis of these arti c les showed Hp no protective impact to BE (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.58–1.10; P = 0.17; I2 = 66%) although with decreased heterogeneity. In contrast, studies that defined Hp exclusively from esophageal biopsies tended to find a positive association between Hp and BE [18]. Hp directly damages the esophageal mucosa with bacterial products, increases the production of prostaglandin, sensitizes the afferent nerve, reduces the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter, and increases acidity via Gastrin, an oncogenic growth factor that contributes to esophageal carcinogenesis [84,85,86,87,88]. Due to the lack o f classified discussion on the severity of gastric mucosal lesions after Hp infection in those included publications, our study is not able to prove the potential protective effect of Hp on BE might be explained by decreased acid secretion due to corpus-predominant gastritis. There are limited studies on the relationship between the duration, site, and severity of Hp infection and BE, and further disc ussions on classification are yet to be conducted.

In subgroup analyses based on different definitions of control and BE, we found that the inverse relationship disappeared when comparing BE with GERD control, and when BE was defined as a change other than IM. Conversely, the OR values of the other subgroups decreased to some extent. In particular, the prevalence of Hp infection in the normal control (population or primary care people) was much lower than that in patients with BE compared to the endoscopy subgroup. We also found that Hp was negatively correlated with LSBE, and that Hp infection could reduce BE dysplasia; however, there was no apparent correlation between Hp and SSBE. When it came to different detection methods for Hp, we found that the inverse relationship disappeared in the Hp infection history subgroup. Serological detection, treatment history, or infection history of Hp cannot reflect the current infection status of the study subjects, which will increase the uncertainty of information. In the present infected subgroup, our meta-analysis discovered a protective association between Hp and BE that was not present in the Hp infection history subgroup.

A few studies without obvious selection and information bias have reported a reduced risk of BE in people infected with Hp [18, 38, 53, 71]. The relationship between Hp infection and BE is controversial due to the considerable heterogeneity observed in most studies; indeed, significant heterogeneity was also noted in the current meta-analysis. A study by Fischbach et al. identified selection and information bias as potential sources of heterogene ity [71].

Subgroup analyses of the GERD and normal control (population or primary care people) showed a decrease of heterogeneity to 33% and 0%, respectively. The endoscopy subgroup might be one of the greatest sources of heterogeneity, since endoscopy might be associated with multiple gastrointestinal diseases. Applying subjects undergoing endoscopy, who were more likely to be colonized with Hp than the general population, as control, would lead to selection bias [38]; however, it also represents the most common and easiest control group. In the same way, blood donors cannot represent the population because they are likely to be healthier and younger [15]. Subject from the same geographical area as the BE patient would be the best choice of control.

A final, but no less important finding was that a significant decrease in overall heterogeneity was also observed when performing subgroup analyses based on whether or not a match was made for sex and age. Males and aging have been shown to be risk factors for Hp infection and BE, and in the current study, the protective effect of Hp infection wasn’t presented when matching both sex and/or age (OR = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.50–1.05; P = 0.09; I2 = 76%) [12, 13, 36, 38, 40, 44, 51, 60]. This result might be influenced by heterogeneity in definition of control group, definition of BE, Hp detection method, age, sex and so on. We collected information about whether or not the BE and control subjects were matched in sex, age, obesity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and race. However, it is unfortunate that, due to too many interfering factors, there were too few studies in single factor subgroups to perform additional subgroup analyses. The heterogeneity of existing studies is great, and a large number of rigorous and precise design studies are still needed to obtain more convincing conclusions.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results showed a statistically significant inverse relationship between the prevalence of Hp, especially CagA-positive Hp strain, with BE. The prevalence of Hp was not significantly different between patients with BE and GERD controls, suggesting that this protective effect of Hp is probably mediated by a de crease in the prevalence of GERD. In addition, Hp was negatively correlated with LSBE, and Hp infection could reduce the BE dysplasia; however, there was no clear correlation between Hp and SSBE. In addition, th e inverse relationship between Hp and BE disappeared in the Hp infection history subgroup. The heterogeneity of existing studies is great. To understand the extent to which Hp reduces the risk of BE, further well-designed studies are needed. Researchers should pay attention to, but not only to, the definition of the control group, the definition of BE, status of Hp infection, sampling site, gastritis type, sex, age, obesity, smoking, alcohol, and race.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Hp :

-

Helicobacter pylori

- BE:

-

Barrett’s esophagus

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- LSBE:

-

Long-segment BE

- SSBE:

-

Short-segment BE

- USBE:

-

Ultra-short-segment BE

- EAC:

-

Esophageal adenocarcinomas

- CagA:

-

Cytotoxin-associated gene A

- NOS:

-

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

- IM:

-

Intestinal metaplasia

- CM:

-

Columnar metaplasia

- S:

-

Serology

- R:

-

Rapid urease test

- U:

-

Urea breath test

- H:

-

Histology

- T:

-

Treatment history

- C:

-

Culture

- NUD:

-

Non-ulcer dyspepsia

- HGD:

-

High grade dysplasia

- SCJ:

-

Squamous Columnar Junction

- EGJ:

-

Esophagogastric junction

References

Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, Suen MMY, Underwood FE, Tanyingoh D, Malfertheiner P, Graham DY, Wong VWS, Wu JCY, et al. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(2):420–9.

Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(18):5191–204.

Edgren G, Adami HO, Weiderpass E, Nyren O. A global assessment of the oesophageal adenocarcinoma epidemic. Gut. 2013;62(10):1406–14.

Cook MB, Chow WH, Devesa SS. Oesophageal cancer incidence in the United States by race, sex, and histologic type, 1977–2005. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(5):855–9.

Sharma P. Clinical practice. Barrett’s esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2548–56.

Perez N, Taylor W. Epidemiology of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Med Stud. 2019;35(1):61–8.

Qumseya BJ, Bukannan A, Gendy S, Ahemd Y, Sultan S, Bain P, Gross SA, Iyer P, Wani S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90(5):707-717.e701.

Arora Z, Garber A, Thota PN. Risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. J Dig Dis. 2016;17(4):215–21.

Møller H, Heseltine E, Vainio H. Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon, 7–14 June 1994. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241.

Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal disease: wake-up call? Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):1819–22.

Sonnenberg A, Turner KO, Spechler SJ, Genta RM. The influence of Helicobacter pylori on the ethnic distribution of Barrett’s metaplasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(2):283–90.

Ferrández A, Benito R, Arenas J, García-González MA, Sopeña F, Alcedo J, Ortego J, Sainz R, Lanas A. CagA-positive Helicobacter pylori infection is not associated with decreased risk of Barrett’s esophagus in a population with high H. pylori infection rate. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6:1–10.

Chen CC, Hsu YC, Lee CT, Hsu CC, Tai CM, Wang WL, Tseng CH, Hsu CT, Lin JT, Chang CY. Central obesity and H. pylori infection influence risk of Barrett’s esophagus in an Asian population. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167815.

Wang Z, Shaheen NJ, Whiteman DC, Anderson LA, Vaughan TL, Corley DA, El-Serag HB, Rubenstein JH, Thrift AP. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with reduced risk of Barrett’s esophagus: an analysis of the barrett’s and esophageal adenocarcinoma consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(8):1148–55.

Erőss B, Farkas N, Vincze Á, Tinusz B, Szapáry L, Garami A, Balaskó M, Sarlós P, Czopf L, Alizadeh H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection reduces the risk of Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Helicobacter. 2018;23(4):e12504.

Liu FX, Wang WH, Shuai XW. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis. Chin J Evid Based Med. 2008;8(12):1086–93.

Wang C, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Helicobacter pylori infection and Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):492–500 (quiz 491, 501).

Fischbach LA, Nordenstedt H, Kramer JR, Gandhi S, Dick-Onuoha S, Lewis A, El-Serag HB. The association between Barrett’s esophagus and Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2012;17(3):163–75.

Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Lindenbaum J, Schneidman D, Van Deventer G, Marin-Sorensen M, Weinstein WM. Association of infection due to Helicobacter pylori with specific upper gastrointestinal pathology. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 8):S704-708.

Johansson J, Håkansson HO, Mellblom L, Kempas A, Johansson KE, Granath F, Nyrén O. Risk factors for Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based approach. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42(2):148–56.

Goldblum JR, Richter JE, Vaezi M, Falk GW, Rice TW, Peek RM. Helicobacter pylori infection, not gastroesophageal reflux, is the major cause of inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of gastric cardiac mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(2):302–11.

Peitz U, Hackelsberger A, Günther T, Clara L, Malfertheiner P. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and the pattern of gastritis in Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis. 2001;19(2):164–9.

Ormsby AH, Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Falk GW, Gramlich TL. Cytokeratin immunoreactivity patterns in the diagnosis of short-segment Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2000;119(3):683–90.

O’Connor HJ, Cunnane K. Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease–a prospective study. Ir J Med Sci. 1994;163(8):369–73.

Jonaitis L, Kriukas D, Kiudelis G, Kupčinskas L. Risk factors for erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in a high Helicobacter pylori prevalence area. Medicina. 2011;47(8):434–9.

Gashi Z, Sherifi F, Shabani R. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis—our experience. Med Arch (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2013;67(6):402–4.

Peng S, Xiong LS, Xiao YL, Lin JK, Wang AJ, Zhang N, Hu PJ, Chen MH. Prompt upper endoscopy is an appropriate initial management in uninvestigated chinese patients with typical reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(9):1947–52.

Guenther T, Hackelsberger A, Kuester D, Malfertheiner P, Roessner A. Reflux esophagitis or Helicobacter infection? - diagnostic value of the inflammatory pattern in metaplastic mucosa at the squamocolumnar junction. Pathol Res Pract. 2007;203(12):831–7.

Voutilainen M, Färkkilä M, Mecklin JP, Juhola M, Sipponen P. Classical Barrett esophagus contrasted with Barrett-type epithelium at normal-appearing esophagogastric junction: comparison of demographic, endoscopic, and histologic features. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(1):2–9.

Werdmuller BFM, Loffeld RJLF. Helicobacter pylori infection has no role in the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42(1):103–5.

Lapertosa G. Helicobacter pylori in Barrett’s oesophagus. Histopathology. 1991;18(6):568–70.

Garcia JM, Splenser AE, Kramer J, Alsarraj A, Fitzgerald S, Ramsey D, El-Serag HB. Circulating inflammatory cytokines and adipokines are associated with increased risk of Barrett’s esophagus: a case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(2):229-238.e223.

Hilal J, Kramer JR, Richardson P, Ramsey DJ, Alsarraj A, El-Serag H. Physical activity and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S307–8.

Thrift AP, Kramer JR, Qureshi Z, Richardson PA, El-Serag HB. Age at onset of GERD symptoms predicts risk of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(6):915–22.

Usui G, Sato H, Shinozaki T, Jinno T, Fujibayashi K, Ishii K, Horiuchi H, Morikawa T, Gunji T, Matsuhashi N. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and short-segment/long-segment Barrett’s esophagus in a Japanese population: a large cross-sectional study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;54:439–44.

Aghayeva S, Mara KC, Katzka DA. The impact of Helicobacter pylori on the presence of Barrett’s esophagus in Azerbaijan, a high-prevalence area of infection. Dis Esophagus. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/doz053.

Chuang YS, Wu MC, Wang YK, Chen YH, Kuo CH, Wu DC, Wu MT, Wu IC. Risks of substance uses, alcohol flush response, Helicobacter pylori infection and upper digestive tract diseases—an endoscopy cross-sectional study. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/kjm2.12071.

Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G, Habel L, Zhao W, Leighton P, Rumore G, Quesenberry C, Buffler P, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of Barrett’s oesophagus: a community-based study. Gut. 2008;57(6):727–33.

Csendes A, Smok G, Cerda G, Burdiles P, Mazza D, Csendes P. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in 190 control subjects and in 236 patients with gastroesophageal reflux, erosive esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 1997;10(1):38–42.

Fischbach LA, Graham DY, Kramer JR, Rugge M, Verstovsek G, Parente P, Alsarraj A, Fitzgerald S, Shaib Y, Abraham NS, et al. Association between Helicobacter pylori and Barrett’s esophagus: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(3):357–68.

Hackelsberger A, Gunther T, Schultze V, Manes G, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Roessner A, Malfertheiner P. Intestinal metaplasia at the gastro-oesophageal junction: Helicobacter pylori gastritis or gastro-oesophageal reflux disease? Gut. 1998;43(1):17–21.

Hirota WK, Loughney TM, Lazas DJ, Maydonovitch CL, Rholl V, Wong RKH. Specialized intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: prevalence and clinical data. Gastroenterology. 1999;116(2):277–85.

Öberg S, Peters JH, Nigro JJ, Theisen J, Hagen JA, DeMeester SR, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Helicobacter pylori is not associated with the manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Surg. 1999;134(7):722–6.

Katsinelos P, Lazaraki G, Kountouras J, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Terzoudis S, Tsiaousi E, Gkagkalis S, Trakatelli C, Bellou A, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in Northern Greece: a Prospective study (Barrett’s esophagus). Hippokratia. 2013;17(1):27–33.

Kiltz U, Pfaffenbach B, Schmidt WE, Adamek RJ. The lack of influence of CagA positive Helicobacter pylori strains on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14(9):979–84.

Laheij RJF, Van Rossum LGM, De Boer WA, Jansen JBMJ. Corpus gastritis in patients with endoscopic diagnosis of reflux oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(5):887–91.

Loffeld RJLF, Werdmuller BFM, Kuster JG, Pérez-Pérez GI, Blaser MJ, Kuipers EJ. Colonization with cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains inversely associated with reflux esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. Digestion. 2000;62(2–3):95–9.

Loffeld RJLF, van der Putten ABMM. Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Neth J Med. 2004;62(6):188–91.

Newton M, Bryan R, Burnham WR, Kamm MA. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori in reflux oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 1997;40(1):9–13.

Park JJ, Kim JW, Kim HJ, Chung MG, Park SM, Baik GH, Nah BK, Nam SY, Seo KS, Ko BS, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus in a Korean population: a nationwide multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43(10):907–14.

Paull G, Yardley JH. Gastric and esophageal Campylobacter pylori in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(1):216–8.

Rajendra S, Ackroyd R, Robertson IK, Ho JJ, Karim N, Kutty KM. Helicobacter pylori, ethnicity, and the gastroesophageal reflux disease spectrum: a study from the East. Helicobacter. 2007;12(2):177–83.

Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, Bolling-Sternevald E, Vieth M, Stolte M, Talley NJ, Agreus L. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the general population: an endoscopic study. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(6):1825–31.

Rubenstein JH, Inadomi JM, Scheiman J, Schoenfeld P, Appelman H, Zhang M, Metko V, Kao JY. Association between Helicobacter pylori and Barrett’s esophagus, erosive esophagitis, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(2):239–45.

Sharifi A, Dowlatshahi S, Moradi Tabriz H, Salamat F, Sanaei O. The prevalence, risk factors, and clinical correlates of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in iranian patients with reflux symptoms. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/696294.

Sonnenberg A, Lash RH, Genta RM. A national study of Helicobactor pylori infection in gastric biopsy specimens. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):1894-1901.e1892 (quiz e1812).

Thrift AP, Pandeya N, Smith KJ, Green AC, Hayward NK, Webb PM, Whiteman DC. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risks of Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(10):2407–16.

Vaezi MF, Falk GW, Peek RM, Vicari JJ, Goldblum JR, Perez-Perez GI, Rice TW, Blaser MJ, Richter JE. CagA-positive strains of Helicobacter pylori may protect against Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(9):2206–11.

Vicari JJ, Peek RM, Falk GW, Goldblum JR, Easley KA, Schnell J, Perez-Perez GI, Halter SA, Rice TW, Blaser MJ, et al. The seroprevalence of cagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains in the spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(1):50–7.

Weston AP, Badr AS, Topalovski M, Cherian R, Dixon A, Hassanein RS. Prospective evaluation of the prevalence of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with GERD, Barrett’s esophagus, Barrett’s dysplasia, and Barrett’s adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95(2):387–94.

White NM, Gabril M, Ejeckam G, Mathews M, Fardy J, Kamel F, Dore J, Yousef GM. Barrett’s esophagus and cardiac intestinal metaplasia: two conditions within the same spectrum. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(4):369–75.

Zhang J, Chen XL, Wang KM, Guo XD, Zuo AL, Gong J. Relationship of gastric Helicobacter pylori infection to Barrett’s esophagus and gastro-esophageal reflux disease in Chinese. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(5):672–5.

Dore MP, Pes GM, Bassotti G, Farina MA, Marras G, Graham DY. Risk factors for erosive and non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s esophagus in Nothern Sardinia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51(11):1281–7.

Keyashian K, Hua V, Narsinh K, Kline M, Chandrasoma PT, Kim JJ. Barrett’s esophagus in Latinos undergoing endoscopy for gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26(1):44–9.

Vieth M, Masoud B, Meining A, Stolte M. Helicobacter pylori infection: protection against Barrett’s mucosa and neoplasia? Digestion. 2000;62(4):225–31.

Wu JC, Sung JJ, Chan FK, Ching JY, Ng AC, Go MY, Wong SK, Ng EK, Chung SC. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with milder gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14(4):427–32.

Zaninotto G, Portale G, Parenti A, Lanza C, Costantini M, Molena D, Ruol A, Battaglia G, Costantino M, Epifani M, et al. Role of acid and bile reflux in development of specialised intestinal metaplasia in distal oesophagus. Dig Liver Dis. 2002;34(4):251–7.

Abe Y, Iijima K, Koike T, Asanuma K, Imatani A, Ohara S, Shimosegawa T. Barrett’s esophagus is characterized by the absence of Helicobacter pylori infection and high levels of serum pepsinogen I concentration in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(1):129–34.

Anderson LA, Murphy SJ, Johnston BT, Watson RGP, Ferguson HR, Bamford KB, Ghazy A, McCarron P, McGuigan J, Reynolds JV, et al. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric atrophy and the stages of the oesophageal inflammation, metaplasia, adenocarcinoma sequence: results from the FINBAR case-control study. Gut. 2008;57(6):734–9.

Csendes A, Smok G, Burdiles P, Sagastume H, Rojas J, Puente G, Quezada F, Korn O. “Carditis”: an objective histological marker for pathologic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 1998;11(2):101–5.

Kudo M, Gutierrez O, El-Zimaity HMT, Cardona H, Nurgalieva ZZ, Wu J, Graham DY. CagA in Barrett’s oesophagus in Colombia, a country with a high prevalence of gastric cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(3):259–62.

Rugge M, Russo V, Busatto G, Genta RM, Di Mario F, Farinati F, Graham DY. The phenotype of gastric mucosa coexisting with Barrett’s oesophagus. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54(6):456–60.

Dietz J, Chaves-e-Silva S, Meurer L, Sekine S, De Souza AR, Meine GC. Short segment Barrett's esophagus and distal gastric intestinal metaplasia. Arquivos de gastroenterologia 2006;43(2):117–20.

Chang Y, Liu B, Liu GS, Wang T, Gong J. Short-segment Barrett’s esophagus and cardia intestinal metaplasia: a comparative analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(48):6151–4.

Dietz J, Meurer L, Maffazzoni DR, Furtado AD, Prolla JC. Intestinal metaplasia in the distal esophagus and correlation with symptoms of gastroesphageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16(1):29–32.

Matsuzaki J, Suzuki H, Asakura K, Saito Y, Hirata K, Takebayashi T, Hibi T. Etiological difference between ultrashort- and short-segment Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(3):332–8.

Rokkas T, Pistiolas D, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and esophageal neoplasia: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(12):1413–7 (1417.e1411-1412).

Buttar NS, Falk GW. Pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux and Barrett esophagus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):226–34.

Abe Y, Ohara S, Koike T, Sekine H, Iijima K, Kawamura M, Imatani A, Kato K, Shimosegawa T. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and the status of gastric acid secretion in patients with Barrett’s esophagus in Japan. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(7):1213–21.

Reshetnyak VI, Burmistrov AI, Maev IV. Helicobacter pylori: commensal, symbiont or pathogen? World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(7):545–60.

Abrahami D, McDonald EG, Schnitzer ME, Barkun AN, Suissa S, Azoulay L. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer: population-based cohort study. Gut. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325097.

Cheung KS, Chan EW, Wong AYS, Chen L, Wong ICK, Leung WK. Long-term proton pump inhibitors and risk of gastric cancer development after treatment for Helicobacter pylori: a population-based study. Gut. 2018;67(1):28–35.

Falk GW. Evaluating the association of Helicobacter pylori to GERD. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;4(9):631–2.

Kountouras J, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D, Katsinelos P. Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet (London, England). 2006;368(9540):986 (author reply 986-987).

Abdel-Latif MM, Windle H, Terres A, Eidhin DN, Kelleher D, Reynolds JV. Helicobacter pylori extract induces nuclear factor-kappa B, activator protein-1, and cyclooxygenase-2 in esophageal epithelial cells. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(4):551–62.

Kountouras J, Chatzopoulos D, Zavos C. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori might halt the progress to oesophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and Barrett’s oesophagus. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(5):1174–5.

Chu YX, Wang WH, Dai Y, Teng GG, Wang SJ. Esophageal Helicobacter pylori colonization aggravates esophageal injury caused by reflux. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(42):15715–26.

Liu FX, Wang WH, Wang J, Li J, Gao PP. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma formation in a rat model of chronic gastroesophageal reflux. Helicobacter. 2011;16(1):66–77.

Acknowledgements

We thank all authors who provided data for this meta-analysis.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y-LD carried out the study selection and drafted the manuscript; Y-LD and R-QD contributed to extraction and analysis of the data. L-PD designed and supervised the study. All authors commented on drafts of the paper and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Du, YL., Duan, RQ. & Duan, LP. Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with reduced risk of Barrett’s esophagus: a meta-analysis and systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol 21, 459 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-02036-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-02036-5