Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate and compare the outcomes of palliative endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS) and complete stone removal among elderly patients with choledocholithiasis using propensity score matching.

Methods

From April 2012 to October 2017, 161 patients aged 75 years and older with choledocholithiasis underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography at our institution. Among them, 136 (84.5%) had complete stone removal, and 25 (15.5%) underwent palliative EBS without further intervention until symptom occurrence. The median age of the EBS group was significantly higher than that of the complete stone removal group. The proportion of patients with dementia, cerebral infarction, preserved gallbladder with gallstones, and surgically altered anatomy was higher in the EBS group than in the complete stone removal group. Propensity score matching was used to adjust for different factors. In total, 50 matched patients (n = 25 in each group) were analyzed.

Results

The median duration of cholangitis-free periods was significantly shorter in the EBS group (596 days) than in the complete stone removal group. About half of patients in the EBS group required retreatment and rehospitalization for cholangitis during the observation period. Cholangitis was mainly caused by stent migration. There was no significant difference in terms of mortality rate and procedure-related adverse events between the two groups. Death was commonly attributed to underlying diseases. However, one patient in the EBS group died due to severe cholangitis.

Conclusions

Palliative EBS should be indicated only to patients with choledocholithiasis who have a poor prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Choledocholithiasis commonly occurs during the migration of gallstones from the gallbladder to the biliary tree. Gallstones are caused by the lower contractility of the biliary epithelium due to multiple factors including supersaturation of cholesterol in the bile, inadequate bile salt concentration and function, diet, hormone levels, and genetic predisposition [1, 2]. Furthermore, the incidence of choledocholithiasis increases with age [3]. Minimally invasive endoscopic procedures play an important role in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Stone removal via endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is the first choice for the management of choledocholithiasis in recent years [4]. However, in some cases, complete stone removal can be challenging to perform due to patient characteristics such as age and underlying diseases, surgically altered anatomy, and stone factors including size and number [5]. Further, additional surgical cholecystectomy cannot be performed in elderly patients with poor general conditions who have undergone complete stone removal from the bile duct via ERCP. Thus, stone recurrence may occur [6,7,8]. In recent years, due to the aging population, palliative endoscopic biliary stenting (EBS) is sometimes the treatment of choice for high-risk elderly patients. EBS alone is associated with good survival among elderly patients who have not undergone complete stone removal [9,10,11]. Furthermore, some studies have shown that EBS can reduce the number and size of stones and facilitate stone removal for a period of time [12,13,14,15]. However, it is associated with stent-related complications such as stent occlusion and migration, and the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines state that management should aim at periodic stent replacement and eventual stent removal, without recommendations for permanent EBS [4]. Moreover, the efficacy of palliative EBS among frail elderly patients with choledocholithiasis remains controversial.

Large, high-quality studies conducted in the 1990s have reported the outcomes of palliative EBS [16, 17]. Since then, the aging of society has advanced. Furthermore, treatment techniques available for “difficult stones” are rapidly improving, and multiple large stones and surgically altered anatomy can now be managed endoscopically. However, in these previous studies, many younger patients were included, and cases of surgically altered anatomy were not included. Therefore, the efficacy of palliative EBS and duct clearance in elderly patients should be assessed and compared again at present. Therefore, this study aimed to retrospectively evaluate and compare the outcomes of palliative EBS and complete stone removal among elderly patients with choledocholithiasis using propensity score matching (PSM).

Methods

Study population

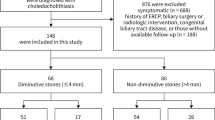

The present study was approved by the institutional review board of Nara Medical University Ethics Committee (#1360). Figure 1 shows the patient flow chart in this study. From April 2012 to October 2017, 278 patients with primary choledocholithiasis underwent ERCP treatment at our institution. Among them, 109 who were aged younger than 75 years and 8 who had an unsuccessful ERCP were excluded from the study. Meanwhile, the remaining 161 patients were included in the analysis. In total, 136 (84.5%) patients had complete stone removal, and 25 (15.5%) underwent palliative EBS without further intervention until symptom occurrence. Patients with recurrence of choledocholithiasis following stone removal were not included in this study. The physician performed either complete stone removal or palliative EBS based on the patient’s condition and stone status. The EBS group also included cases in which stone removal was initially attempted but was difficult, and thereby palliative stenting was unavoidable with the stone remaining. None of the patients had routine or planned stent replacement. Patients who could visit our hospital were followed up every few months with blood tests and imaging examinations. Information regarding patient characteristics and endoscopic procedures was obtained from the medical records. We contacted the patients whose hospital visits were interrupted early and the families of such patients by phone, in addition to contacting their medical institutions to conduct as much prognostic research as possible. All authors had access to the study data and approved the final manuscript. This single-center retrospective study was performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement. Owing to the retrospective nature of this study, an opt-out approach was used instead of the requirement of written informed consent for participation in the study.

ERCP

Patients were placed in prone position and were sedated with midazolam and buprenorphine hydrochloride, or haloperidol as appropriate. Vital signs were monitored with electrocardiogram and oxygen saturation assessment during ERCP. Patients received oxygen therapy via nasal cannula if needed. ERCP was performed using standard duodenoscopes (TJF260V and JF260V; Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan). A balloon-assisted endoscope (EC-450BL5; Fujifilm Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used in all patients with surgically altered anatomy (except for the Billroth I method). Selective bile duct cannulation was performed with wire-guided cannulation and contrast medium injection methods using a standard ERCP catheter (MTW ERCP catheter; Medi-Globe GmbH, Rohrdorf, Germany) or a sphincterotome (CleverCut 3 V; Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan). EBS was performed using straight or pigtail plastic stents. In patients who underwent endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD), a 6- to 10-mm balloon catheter (HurricaneTM RX; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was used for balloon dilation. Endoscopic large balloon dilation (EPLBD) was performed using a 12- to 20-mm balloon catheter (CRE wire-guided balloon dilator; Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan). In this study, none of the patients received rectal indomethacin during the periprocedural period.

PSM

Table 1 shows the characteristics of patients. Although our study population was older than 75 years, a significant difference was noted in median age between the EBS group and the stone removal group in the total cohort before PSM. The EBS group had a significantly higher proportion of patients with dementia, history of brain stroke, preserved gallbladder with gallstones, surgically altered anatomy, periampullary diverticulum, and large bile duct and stones. However, there was no significant difference in stone number between the EBS and complete stone removal groups. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in stone number between the EBS and complete stone removal groups. No case of ERCP was observed in any of the patients with WHO performance status 4 in the either of the groups.

PSM was performed to control for factors affecting the choice between complete stone removal and bile duct stenting. Two groups were matched at a 1:1 ratio (stone removal, n = 25; palliative EBS, n = 25) via a propensity score-matched analysis adjusted for 14 covariates (age, sex, WHO performance status, antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, cardiovascular disease, dementia, history of cerebral infarction, malignant neoplasm, gallstone status, periampullary diverticulum, surgically altered anatomy, diameter of the common bile duct, diameter of stones, and number of stones) for minimizing inherent bias. Each patient in the EBS group was matched to a patient in the stone removal group using the nearest-neighbor method with a caliper range of 0.20 of the standard deviation of the pooled propensity scores. All patient factors were eventually matched, and there was no significant difference between the two groups.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables using the t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The duration of cholangitis-free periods was assessed using the Kaplan–Meier method and was compared between the two groups with the log-rank test. The duration of cholangitis- and death-free periods was censored at the end of each patient’s follow-up period. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (version 1.41; Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan; http://www.jichi.ac.jp/saitama-sct/SaitamaHP.files/statmedEN.html), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.0.3) [18].

Endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint of our study was the time to recurrence of cholangitis after complete stone removal and palliative EBS among elderly patients with choledocholithiasis. The secondary endpoints were causes and severity of cholangitis, incidence of adverse events (AEs), mortality rate, and causes of death. If cholangitis developed after ERCP, its diagnosis and severity were defined according to the Tokyo Guideline 2018 [19]. Early AEs were defined as AEs occurring within 14 days, and late AEs as AEs occurring after 14 days after the procedure. AE severity was graded according to the ASGE lexicon [20].

Results

Endoscopic procedure and AEs

Table 2 depicts the endoscopic procedures. Three (12.0%) patients in the EBS group received ampullary interventions. These three patients had initially undergone ampullary interventions in an attempt to remove the stone completely, but it was difficult and the procedure was changed to palliative stenting with the stone remaining. Meanwhile, all patients in the stone removal group, including 18 (72.0%), 1 (4.0%), and 6 (24.0%) who underwent endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES), EPBD alone, and EPLBD with ES, respectively, had ampullary interventions. In the EBS group, straight-type plastic and pigtail-type stents were used in 68.0% and 32.0% of patients, respectively. The most common stents used were 7 cm in length and 7 F in diameter. The number of ERCP sessions was slightly higher in the stone removal group than in the EBS group. The procedure time was significantly shorter in the EBS group than in the stone removal group. Table 2 shows data about AEs other than cholangitis. In the EBS group, early AEs included acute pancreatitis (n = 1), aspiration pneumonia (n = 1), and retroperitoneal perforation (n = 1). In addition, one patient presented with acute cholecystitis, which is considered a late AE. Two patients in the stone removal group had acute pancreatitis. The incidence of AEs did not significantly differ between the EBS and complete stone removal groups (16.0% and 8.0%, p = 0.67). There were no procedure-related deaths in both groups.

Duration of cholangitis-free periods

The Kaplan–Meier curve for cholangitis-free duration is shown in Fig. 2. The median cholangitis-free period in the EBS group was 596 days (95% confidence interval, 187–1240 days); however, the median cholangitis-free period in the stone removal group could not be estimated during the observation period. The stone removal group had significantly longer cholangitis-free period than the EBS group (Log-Rank test; p < 0.01). Table 3 shows the incidence, cause, and severity of cholangitis. About half of patients in the EBS group developed cholangitis, and it was significantly more common in the EBS group than in the stone removal group (p < 0.01). Stent migration was the most common cause of cholangitis in the EBS group. We also investigated the correlation between stent geometry and migration (Table 4) and found no significant difference in the frequency of stent migration between the pigtail and straight types of stents.

Furthermore, one patient in the EBS group had stent–stone complex. Thus, the old stent was difficult to remove (Fig. 3). By contrast, only one patient in the complete stone removal group presented with cholangitis, which was caused by recurrence of bile duct stones. All patients with cholangitis were treated again with ERCP, and all reinterventions were technically successful. Most patients presented with moderate cholangitis. However, one patient in the EBS group died due to severe cholangitis.

Stent–stone complex. One patient in the palliative EBS group had stent–stone complex. He developed cholangitis 3 years after the initial ERCP stent placement. ERCP was performed again, and the stent ruptured upon removal (EBS, endoscopic biliary stenting; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography)

Mortality

During a median observation period of 442.5 (range: 8–2364) days, 3 (12.0%) patients in the EBS group and 2 (8.0%) in the complete stone removal group died. There was no significant difference in terms of mortality rate between the two groups. Death was commonly caused by underlying diseases. However, one patient in the EBS group died due to severe cholangitis. The length of hospital stay was also examined, and the result did not significantly differ between the two groups (Table 3).

Discussion

Endoscopic lithotripsy is the first choice for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Minimally invasive endoscopic treatment, which is safe even among frail elderly patients with underlying diseases, has been increasingly used. However, in actual clinical practice, patients may not endure long procedures. Thus, the procedure can be discontinued, thereby leaving a biliary stent alone. Bergman et al. assessed the outcomes of long-term treatment with 10-F polyethylene stents among elderly patients (n = 58) [16]. This method was initially successful. However, over time, 38% of patients developed recurrent cholangitis; in 12% of cases, it was fatal. Chopra et al. found that ductal clearance was consistently associated with a higher rate of procedural AEs in a randomized comparison between ductal clearance and long-term biliary stenting (16% vs. 7%). However, the incidence of long-term biliary AEs was lower (14% vs. 36%) [17]. By contrast, there are some reports showing that long-term stenting is beneficial for high-risk elderly patients with choledocholithiasis [9,10,11]. However, the validity of long-term EBS remains controversial.

In retrospective studies comparing complete stone removal and long-term EBS, selection bias is more likely to occur because a high number of elderly patients and those with poor general health are included in the EBS group. In this study, this bias was eliminated by including only patients aged 75 years and older in the target population and by matching patient factors between the two groups via PSM.

Interestingly, when we compared the background characteristics of patients before PSM in our study, we found significant differences in terms of patient factors (such as age and underlying diseases) and anatomical factors (including periampullary diverticulum and surgically altered anatomy). However, there was no significant difference in terms of the number of stones. Furthermore, the patients in the EBS group were more likely to have larger stones. Nevertheless, the median diameter was only 10 mm. In recent years, the technique used to remove the so-called difficult stones has significantly improved. New ampullary interventions, including EPLBD, were found to be useful in the treatment of large and multiple stones [21,22,23]. Moreover, lithotripsy techniques including electronic hydraulic lithotripsy using a digital-single-operator cholangioscopy have also been developed [24, 25]. This suggests that the general condition of the patients, rather than stone factors, affects the choice of palliative EBS. In addition, in the total cohort before PSM, the EBS group had a significantly higher proportion with surgically altered anatomy. In recent years, ERCP with a balloon-assisted endoscope has been found to be effective in patients with surgically altered anatomy [26,27,28]. However, the technique is still challenging. This might increase the number of cases in which the stones are not completely removed, even after a successful ERCP, and the procedure was discontinued with stenting performed alone.

Indeed, there were some cases in the EBS group in which the procedure required an extensive amount of time, even for stenting alone, caused by the difficulty of scope insertion in patients with surgically altered anatomy. As shown in Table 2, the procedure time in the palliative EBS group varied (range 5–181 min). No significant difference was noted in the incidence of procedure-related AEs between the two groups, but the incidence of AEs tended to be slightly higher in the EBS group. This finding may be associated with the fact that there were some high-risk patients in the EBS group who underwent prolonged procedures, as described above, or who were initially planned to undergo stone removal that was discontinued midway through the procedure and instead underwent palliative stenting. There were no procedure-related deaths in either of the groups. In contrast, the median time to cholangitis was significantly shorter in the EBS group than in the complete stone removal group. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of treatment safety or length of hospital stay. Nevertheless, about half of the patients in the EBS group eventually required reintervention and rehospitalization. More importantly, one patient in the EBS group died due to severe cholangitis. In the EBS group, the main cause of stent dysfunction was stent migration, which might have been caused by the fact that the stent was placed in the bile duct without stenosis. It was difficult to control migration, even with pigtail-type stents. Additionally, in our study, there was a case of stent–stone complex in the EBS group. Kaneko et al. showed that long-term EBS increases the risk of stent–stone complex [29]. Stent–stone complex formation can lead to difficulties in removing old stents via conventional endoscopic procedures. Therefore, palliative EBS may be acceptable in patients with malignancies who have a poor prognosis. However, the indications should be limited. Even in cases in which biliary stenting was unavoidable at the time of initial treatment, it may be necessary to perform the procedure again, after the patient’s general condition improves, to achieve complete stone removal or to consider planned stent replacement [30].

By contrast, the present study showed a relatively long duration of cholangitis-free period in the EBS group (596 days). By employing a transpapillary stent placement approach in the bile duct, even if the stent was occluded, the impaction of the stones on the duodenal papilla could have been inhibited and incidence of cholangitis may have been less likely. This study also included some cases of patients with surgically altered anatomy; incidence of stent occlusion was possibly less likely in these cases because food residue did not pass through the afferent limb.

In addition, in some elderly patients with choledocholithiasis, even if the bile duct stones are removed via ERCP, the gallbladder stones may not be surgically resected thereafter. In our study, even in the matched cohort adjusted for the proportion of patients with residual gallbladder with gallstones after ERCP, the incidence of cholangitis was significantly lower in the stone removal group. Yasui et al. showed that the recurrence of choledocholithiasis did not increase even if the gallbladder with gallstones is preserved after endoscopic treatment of choledocholithiasis among elderly patients [31]. Therefore, regardless of whether cholecystectomy is feasible in the future, a reasonable therapeutic strategy should be used to completely remove bile duct stones.

The current study had several limitations. First, patients with inadequate follow-up were included. This study included several frail and elderly patients with underlying medical conditions. In some cases, regular outpatient visits were challenging. Therefore, long-term prognosis could not be assessed in such cases. We attempted to conduct as much prognostic research as possible through follow-up of the patients using telephone surveys and inquiries to their medical institutions, however, we may have failed to detect mild cases of cholecystitis and cholangitis. In our study, the incidence of cholangitis and cholecystitis was lower in the stone removal group, and the duration of the cholangitis-free period was relatively longer in the EBS group. However, we cannot deny the possibility that the incidence of cholecystitis and cholangitis noted in both groups may have been lower than the actual incidence. Second, this is a retrospective study, which may not be as statistically reliable as randomized control trials. However, conducting a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing EBS and stone removal in frail and elderly patients is not easy. In this study, the background characteristics of the stone removal group and the EBS group were adjusted using PSM to ensure homogeneity between the two groups. We believe that the statistical reliability of this study is sufficient. Third, because the outcome of the study was the occurrence of cholangitis, the exact recurrence rate of choledocholithiasis in the stone removal group remains unknown. However, we believe that the incidence of cholangitis is more important than the recurrence rate of stones in clinical practice. Therefore, this study is considered more relevant to actual clinical practice.

In conclusion, palliative EBS was effective in controlling cholangitis for a certain period of time among frail elderly patients with choledocholithiasis. However, a significantly higher number of patients required reintervention and rehospitalization for cholangitis in the EBS group than in the complete stone removal group. The median duration of cholangitis-free periods in the palliative EBS group was significantly shorter than that in the complete stone removal group even after adjusting for background characteristics using PSM. Furthermore, one patient in the EBS group died due to severe cholangitis. Thus, palliative EBS should be indicated only in patients with choledocholithiasis who have a poor prognosis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Paumgartner G, Sauerbruch T. Gallstones: pathogenesis. Lancet. 1991;338:1117–21.

Figueiredo JC, Haiman C, Porcel J, Buxbaum J, Stram D, Tambe N, et al. Sex and ethnic/racial-specific risk factors for gallbladder disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:1–12.

Siegel JH, Kasmin FE. Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut. 1997;41:433–5.

Buxbaum JL, Abbas Fehmi SM, Sultan S, Fishman DS, Qumseya BJ, Cortessis VK, et al. ASGE guideline on the role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:1075–1105.

Yasuda I, Itoi T. Recent advances in endoscopic management of difficult bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2013;25:376–85.

McAlister VC, Davenport E, Renouf E. Cholecystectomy deferral in patients with endoscopic sphincterotomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:Cd006233.

Boerma D, Rauws EAJ, Keulemans YCA, Janssen IMC, Bolwerk CJM, Timmer R, et al. Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:761–5.

Wang CC, Tsai MC, Wang YT, Yang TW, Chen HY, Sung WW, et al. Role of cholecystectomy in choledocholithiasis patients underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1–7.

Sugiura R, Naruse H, Yamato H, Kudo T, Yamamoto Y, Hatanaka K, et al. Long-term outcomes and risk factors of recurrent biliary obstruction after permanent endoscopic biliary stenting for choledocholithiasis in high-risk patients. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:246–51.

Sbeit W, Khoury T, Kadah A, M. Livovsky D, Nubani A, Mari A, et al. Long-term safety of endoscopic biliary stents for cholangitis complicating choledocholithiasis: a multi-center study. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2953.

Ang TL, Fock KM, Teo EK, Chua TS, Tan J. An audit of the outcome of long-term biliary stenting in the treatment of common bile duct stones in a general hospital. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:765–71.

Fan Z, Hawes R, Lawrence C, Zhang X, Zhang X, Lv W. Analysis of plastic stents in the treatment of large common bile duct stones in 45 patients. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:86–90.

Hong WD, Zhu QH, Huang QK. Endoscopic sphincterotomy plus endoprostheses in the treatment of large or multiple common bile duct stones. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:240–3.

Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M, Kato N, Kamijima T, Graham DY, et al. Biliary stenting in the management of large or multiple common bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1200–1203.e2.

Chan AC, Ng EK, Chung SC, Lai CW, Lau JY, Sung JJ, et al. Common bile duct stones become smaller after endoscopic biliary stenting. Endoscopy. 1998;30:356–9.

Bergman JJ, Rauws EA, Tijssen JG, Tytgat GNJ, Huibregtse K. Biliary endoprostheses in elderly patients with endoscopically irretrievable common bile duct stones: report on 117 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:195–201.

Chopra KB, Peters RA, O’Toole PA, Williams SGJ, Gimson AES, Lombard MG, et al. Randomised study of endoscopic biliary endoprosthesis versus duct clearance for bileduct stones in high-risk patients. Lancet. 1996;348:791–3.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software “EZR” for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–8.

Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, et al. Tokyo guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17–30.

Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken L, Baron TH, Hutter MM, Jacobson BC, et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446–54.

Itoi T, Ryozawa S, Katanuma A, Okabe Y, Kato H, Horaguchi J, et al. Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society guidelines for endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation. Dig Endosc. 2018;30:293–309.

Kim TH, Kim JH, Seo DW, Lee DK, Reddy ND, Rerknimitr R, et al. International consensus guidelines for endoscopic papillary large-balloon dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:37–47.

Ersoz G, Tekesin O, Ozutemiz AO, Gunsar F. Biliary sphincterotomy plus dilation with a large balloon for bile duct stones that are difficult to extract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:156–9.

Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Kommaraju K, Zhu X, Hebert-Magee S, Hawes RH, et al. Digital, single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy in the diagnosis and management of pancreatobiliary disorders: a multicenter clinical experience (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:649–55.

Maydeo AP, Rerknimitr R, Lau JY, Aljebreen A, Niaz SK, Itoi T, et al. Cholangioscopy-guided lithotripsy for difficult bile duct stone clearance in a single session of ERCP: results from a large multinational registry demonstrate high success rates. Endoscopy. 2019;51:922–9.

Shimatani M, Matsushita M, Takaoka M, Koyabu M, Ikeura T, Kato K, et al. Effective short double-balloon enteroscope for diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy: a large case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:849–54.

Yane K, Katanuma A, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Kin T, Ikarashi S, et al. Short-type single-balloon enteroscope-assisted ERCP in postsurgical altered anatomy: potential factors affecting procedural failure. Endoscopy. 2017;49:69–74.

Shimatani M, Takaoka M, Matsushita M, Okazaki K. Endoscopic approaches for pancreatobiliary diseases in patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomy. Dig Endosc. 2014;26 Suppl 1:70–8.

Kaneko J, Kawata K, Watanabe S, Chida T, Matsushita M, Suda T, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors for stent–stone complex formation following biliary plastic stent placement in patients with common bile duct stones. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:448–54.

Di Giorgio P, Manes G, Grimaldi E, Schettino M, D’Alessandro A, Di Giorgio A, et al. Endoscopic plastic stenting for bile duct stones: stent changing on demand or every 3 months. A prospective comparison study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:1014–7.

Yasui T, Takahata S, Kono H, Nagayoshi Y, Mori Y, Tsutsumi K, et al. Is cholecystectomy necessary after endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones in patients older than 80 years of age? J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:65–70.

Funding

There authors declare that no funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: KK. Data curation: TN. Formal analysis: TA, NN. Investigation: KK, AM, MF. Methodology: KK, AM. Project administration: KK, AM. Resources: KK, TO, YF, YS. Supervision: HY. Writing-original draft: KK. Writing-review and editing: KK, AM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed following the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients before conducting ERCP. Informed consent for study enrollment was obtained in the form of an opt-out on the website. This study protocol was approved by the Nara Medical University Ethics Committee (#1360).

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kitagawa, K., Mitoro, A., Ozutsumi, T. et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety between palliative biliary stent placement and duct clearance among elderly patients with choledocholithiasis: a propensity score-matched analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 21, 369 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01956-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-021-01956-6